Introduction

Although gamebird shooting has been a favoured sport amongst the British landed elite for centuries, levels reached a peak in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, culminating in high-profile shooting parties hosted by many estates owners.Footnote 1 The many game laws passed over the centuries – at least thirty-three from 1761 to 1810 – reinforced the position of this elite and placed severe penalties on poachers.Footnote 2 A 1784 Act, for example, introduced annual game licences and allowed landowners to acquire a licence for an employed gamekeeper.Footnote 3 Game (hare, pheasant, partridge, grouse, heath or moor game, black game, and bustard) was defined by the 1828 Act, while the 1831 Act allowed the licenced sale of game and ended the qualification system for licences, theoretically giving licenced tenant farmers the right to shoot on their land, although this was often prohibited under their leases.Footnote 4 As shooting grew in popularity, pressure for more birds to shoot led to the development of methods for semi-captive rearing of partridge and pheasant and the introduction of beating and the battue. These, alongside the development of the modern breech-loading shotgun, resulted in a fifteen-fold increase in the number of pheasant and partridge shot between 1860 and 1912.Footnote 5 At this time, the employment of gamekeepers to rear and protect the birds (primarily pheasant and partridge in Norfolk), combat poaching, and organise the shoots became widespread across the country.Footnote 6

The gamekeeper has often been portrayed as an interfering busybody, disliked and detested by farmers and poachers, although landowners often found them truthful, straightforward, and conscientious.Footnote 7 To a certain extent, earlier work reflected this dislike by focusing on the poacher, the landowner, or the law rather than the gamekeeper with few studies systematically examining gamekeeper numbers and locations.Footnote 8 Despite the fact that gamekeepers were tabulated by county in the censuses from 1851, older studies used national figures when discussing poaching and gamekeepers at the county level. More recent analyses by Osborne, Osborne, and Winstanley and the current author showed that many counties do not follow national trends and suggested that multiple factors affected gamekeeper numbers in different ways across regions and that national data should not be used in local studies.Footnote 9

Norfolk emerged as a major game-shooting county in the Victorian period, remained popular during the Edwardian period, and continues to be prominent today. From 1861 to 1921, Norfolk had more gamekeepers than any other studied county and showed sustained growth in numbers for many decades.Footnote 10 It is a large predominantly rural county, with diverse underlying geology and extensive agriculture, from cereal growing to rearing of cows and sheep, on estates and farms of varying sizes. This combination of factors makes it an ideal county to explore the numbers and distributions of gamekeepers at a local level over time, including who employed them, as well as testing previous assertions that, in Norfolk, each parish had three or four keepers (Thompson) or that all of Norfolk was ‘keepered’ (Tapper).Footnote 11 In addition, the influence – if any - of poaching, fashion, geology, and agricultural economics, on gamekeeper numbers and locations can be examined.

The primary data source is the detailed census returns (1851–1921), but information on poaching prosecutions, geology, and agricultural history is also utilised. The 1851 census was the first in which gamekeepers were assigned a specific occupation code, making this the earliest census suitable for analysis. The 1921 census marks the end point of useful census data on gamekeepers as the 1931 census returns were destroyed in a fire in 1942 and there was no census in 1941.Footnote 12 By the time of the 1951 census, the data from which will be released around 2052, the gamekeeper was no longer a dominant figure in rural society.

Preparing and analysing the data

Norfolk census returns (1851–1921) provided information on numbers and locations of gamekeepers: the 1871 return had no suitable occupation data and was excluded.Footnote 13 The record for each person included name (except 1921), age, occupation, and occupation code, as well as in which parish and registration district they lived. The 1921 data additionally included employers’ names.Footnote 14 In general, gamekeepers fell under occupation code 88, which, in the instructions to clerks on coding occupations, covered a wide range of related occupations: deer park keeper, coursing slipper, earth stopper, fish keeper (river), keeper of the fox cover, rabbit breeder (plus catcher, destroyer, warrener), water bailiff, water keeper, watcher, river keeper, (plus watcher, warder), decoy man, decoy keeper, trappers (rabbits, etc.), and warren holder.Footnote 15 Some gamekeepers appeared under other occupation codes, and some individuals under code 88 were not gamekeepers, reflecting a degree of inaccuracy in the compilation and analysis of the returns, as has been noted elsewhere (see below also).Footnote 16 Examples include Henry Collier, who, in 1881, was a game food manufacturer but was incorrectly returned under occupation code 88. Gamekeeper appeared in more than twenty variations (gamekeeper, head gamekeeper, under gamekeeper, assistant gamekeeper), all of which were included.Footnote 17

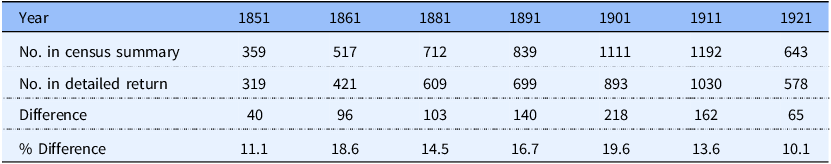

Individual records were examined, and retired, former, and unemployed gamekeepers were excluded, as were warreners and similar occupations, visiting gamekeepers, and children under ten – such as four-year-old John Mathews, who was recorded as a gamekeeper in 1851. Individuals with two occupations, one of which was gamekeeper, were included even if they were not originally recorded under occupation code 88. The small number of females given occupation code 88 – always under twenty and usually under ten – were checked before inclusion with the men, as many were actually inn or housekeepers. Margaret Larner of Ormesby St. Margaret, for example, gave her occupation as H keeper domestic (presumably housekeeper) in 1891 but was allocated to code 88, as was Elizabeth Grower in 1861 who lived at the Golden Anchor public house in Molton: both were excluded. The final cohort of active gamekeepers was between 10 (1921) and 20 (1901) per cent lower than the numbers given in the census summary data (Table 1).Footnote 18 Taking 1891 as an example, the difference was 140, of whom 125 were warreners and retired gamekeepers who were correctly coded but fell outside the scope of this work. The remaining fifteen were accounted for by adding (or removing) visiting gamekeepers, misclassified entries, female and child gamekeepers, and people with multiple occupations. The inclusions and exclusions outlined here ensured that, as far as possible, the selected individuals were actively working as gamekeepers in Norfolk on the census dates.

Table 1. Comparison of gamekeeper numbers in census summaries and detailed returns

The census records underestimate the number of people who worked as gamekeepers for at least part of the year. The censuses were taken in the spring, but as the main bird rearing and shooting seasons were later in the year, those employed in gamekeeping on a casual basis as beaters, for example, or only at peak times, would have been missed. Night watchers, for example, were mostly employed in the winter shooting season.Footnote 19 It would be very difficult to factor in this group of workers, although records from individual estates might shed some light on the extent to which such casual labour is used, but such an analysis is outside the scope of this work.

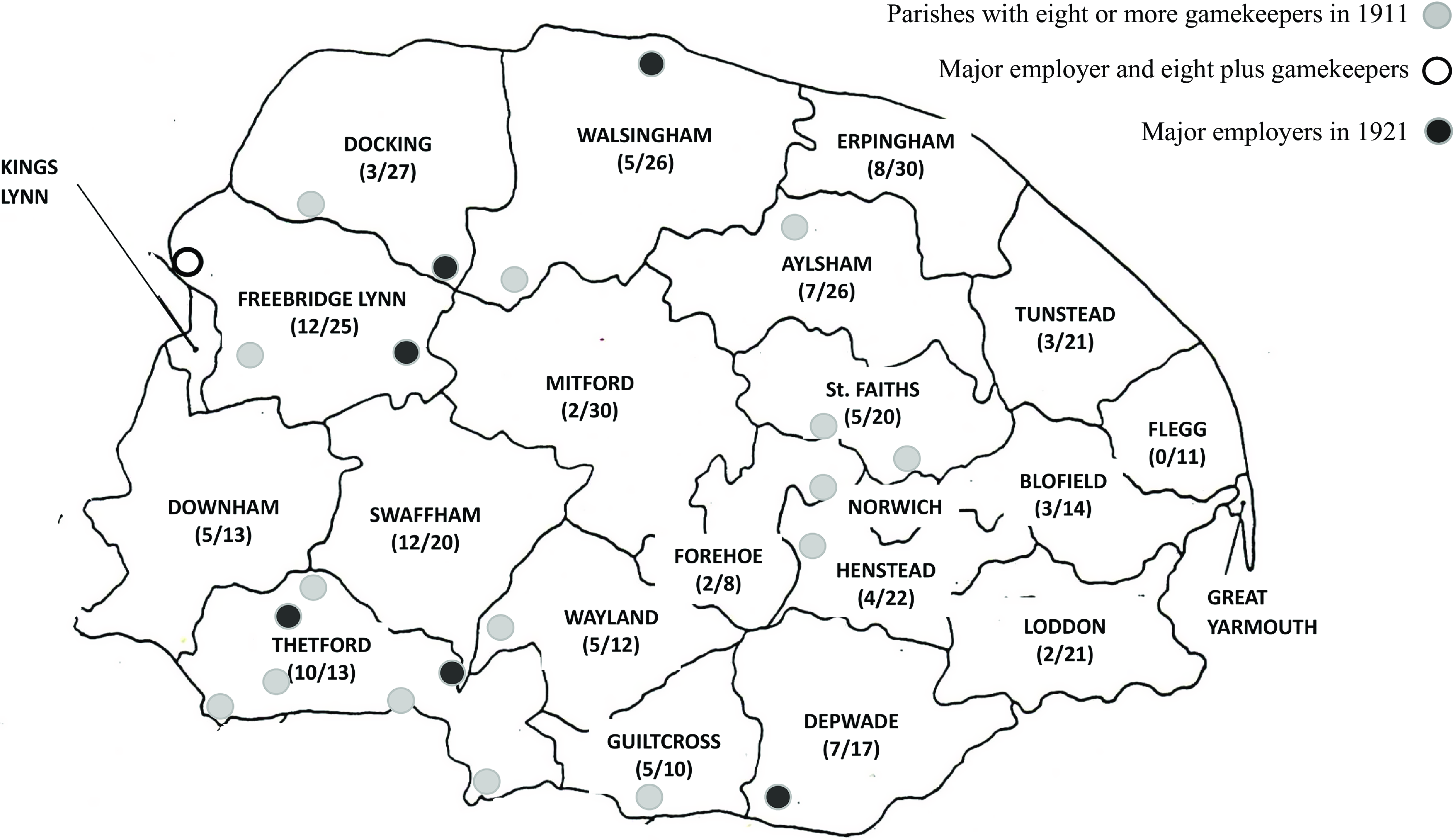

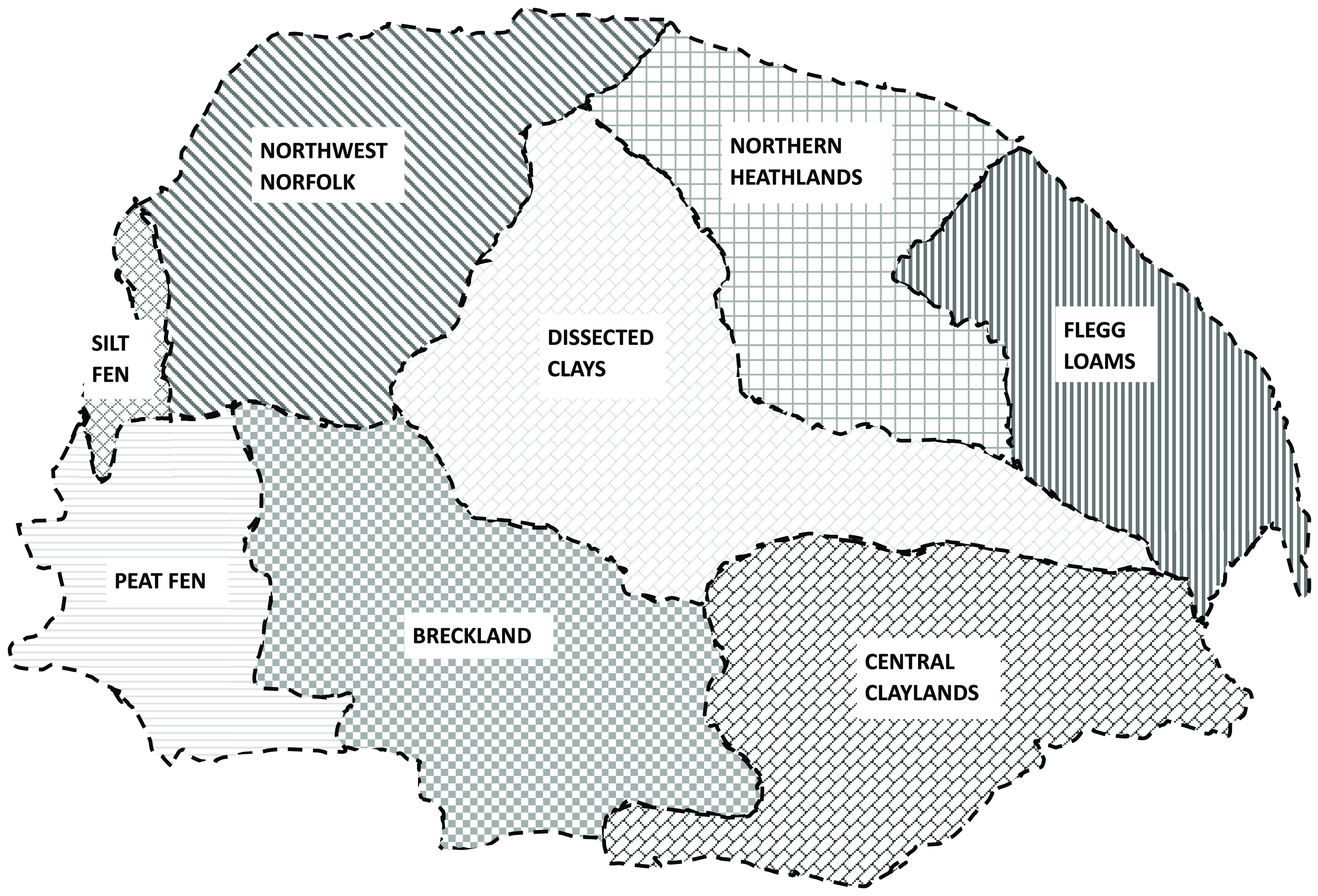

Once all gamekeepers were identified, their parish of abode was assigned to a registration district based on the 1836 poor law areas (Fig. 1).Footnote 20 Allowance was also made for occasional changes to registration districts: Guiltcross, for example, was abolished in 1902 but recreated for the 1911 and 1921 analyses by moving the parishes (and gamekeepers) formerly allocated to Guiltcross out of their post-1902 registration districts. Where parishes moved registration district – Melton Constable, for example, moved from Erpingham to Wayland in 1869 – they were assigned to one district for all years (in this example to Wayland). Care was also taken to ensure that parishes with the same name were distinguished, such as the two Wittons. These adjustments allowed the creation of a consistent data set for the subsequent analyses, with gamekeepers assigned to a parish and parishes assigned to a registration district.

Figure 1. Norfolk registration districts and the distribution of gamekeepers.

The numbers in brackets are the number of parishes with four or more gamekeepers and the total number of parishes with gamekeepers in a district in 1911. Based on Donovan J. Murrells, Registration Districts of Norfolk in 1836: with Maps and List of Parishes (London, 1993), p. 10.

Gamekeepers in the census: 1851–1921

The number of active gamekeepers (i.e. those selected using the criteria outlined above) increased more than threefold in sixty years, from 319 in 1851 to 1030 in 1911, before declining by 46 per cent, to 578, by 1921 (Table 1). The largest increases occurred between 1891 and 1901 and 1901 and 1911. In all censuses, few (less than ten) gamekeepers were recorded from the major urban areas (Norwich, Kings Lynn, Great Yarmouth), so these districts have been excluded from most subsequent analyses.

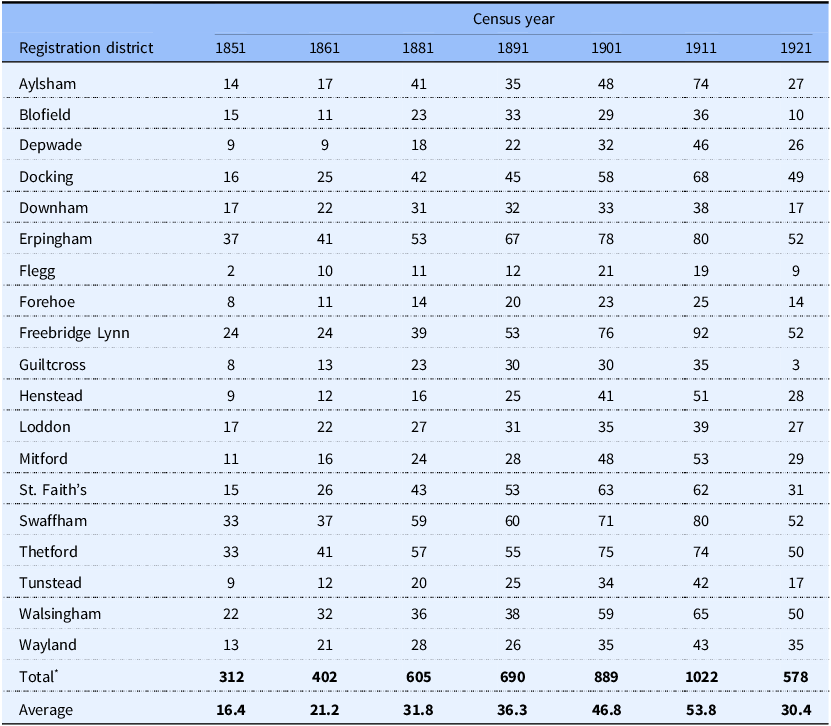

The gamekeepers were not evenly spread across the county. In 1851, on average, there were sixteen gamekeepers per registration district (nineteen rural districts: Table 2), but numbers ranged from two in Flegg to thirty-seven in Erpingham. By 1861, the average had increased to twenty-one, and by 1881, it had reached almost thirty-two per district, ranging from Flegg with eleven to Swaffham with fifty-nine (Table 2). By 1911, the average number of gamekeepers per district was almost fifty-four, more than three times the 1851 level, with a fivefold difference between the highest (Freebridge Lynn: 92) and lowest (Flegg: 18). In 1851, only five districts had twenty or more gamekeepers, but this had increased to 15 by 1881, and by 1911, only Flegg had fewer than twenty (Table 2). Gamekeeper numbers peaked in most districts in 1911, although Flegg and Guiltcross peaked in 1901 and Erpingham and St. Faith’s showed little change between 1901 and 1911. By 1911, ten districts each had more than fifty gamekeepers, but by 1921, only five districts had fifty-plus gamekeepers, and six had fewer than twenty (average 30: Table 2).

Table 2. Number of gamekeepers by registration district and census year

* As this table excludes King’s Lynn, Norwich, and Great Yarmouth, totals differ from those in Table 1.

At the county level, gamekeeper numbers increased continuously between 1851 and 1911, before declining in 1921, but many of the nineteen rural districts demonstrated different trends. Downham, Erpingham, Forehoe, and Walsingham (Table 2) showed a similar growth pattern to the county, but in Depwade and Freebridge Lynn, numbers declined before increasing, while Aylsham and Henstead had periods of growth and stasis. The minimum growth between 1851 and 1911 was a doubling (Blofield, Downham, Erpingham: Table 2), but eight districts showed more than fourfold growth. However, as each of these had fewer than twenty gamekeepers in 1851, this was a comparatively small numerical increase. By 1911, four registration districts along the north coast (Freebridge Lynn, Docking, Walsingham, Erpingham: Fig. 1) each had more than sixty gamekeepers as did Swaffham and Thetford in the southwest and Aylsham and St. Faiths to the north of Norwich. Districts in the east of the county (Fig. 1; Table 2) had fewer gamekeepers than average. Between 1911 and 1921, the total number of gamekeepers in Norfolk dropped by 43 per cent, although individual districts varied. Numbers in Guiltcross dropped by over 90 per cent (Table 2), but in Wayland, the decline was under 20 per cent. In the eight districts with more than sixty gamekeepers in 1911 (Table 2), numbers generally declined by less than Norfolk as a whole, although St. Faith’s and Aylsham had larger drops. Overall, few of the districts followed the amount and timing of the increases (and decrease) of the county, instead demonstrating a variety of starting points, growth rates, and patterns of change.

Several factors contributed to the decline in gamekeeper numbers between 1911 and 1921. Many gamekeepers who volunteered in the First World War were killed or injured and did not return to the profession: nine gamekeepers from the royal estate at Sandringham were killed, for example.Footnote 21 In addition, during the war, the Defence of the Realm Act prohibited the feeding of corn to gamebirds, and restrictions from the Ministry of Food Control stopped gamebird rearing, restricted the availability of shotgun cartridges, and widened the right to shoot pheasants.Footnote 22 Some estates were requisitioned for training camps and hospitals, which often resulted in damage to woodland, fields, and buildings – not to mention poaching by hungry and bored servicemen.Footnote 23 Change continued after the war. The heirs to many estates had been killed, which, coupled with increases in income tax and death duties, resulted in estate sales with almost one-quarter of land estimated to change hands between 1914 and 1927, often to newly wealthy industrialists and bankers.Footnote 24 Finally, although agricultural prices remained buoyant in the immediate post-war period, they collapsed in 1921 after price controls were withdrawn, further increasing the financial pressure on landowners.Footnote 25 Although these factors would have operated to different degrees on individual estates, they were major factors in the decline in the number of gamekeepers seen in 1921, from which they have never recovered.

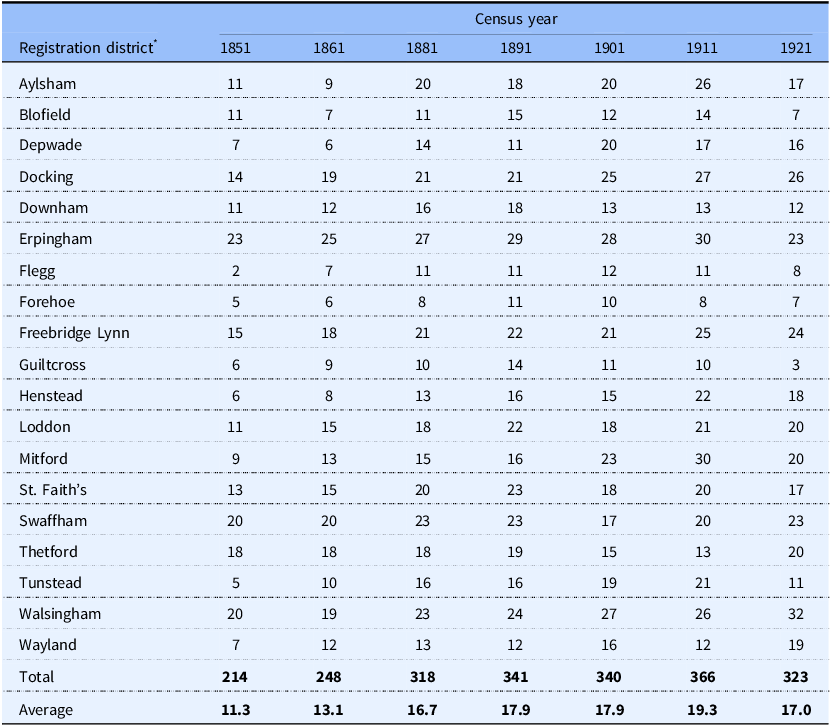

The increases in gamekeeper numbers up to 1911 could have been due to a rise in the number of gamekeepers per parish or in the number of parishes returning gamekeepers or both. In total, just over 580 different parishes reported gamekeepers over the period, giving an average of thirty parishes per district reporting gamekeepers at least once (Table 3). Based on 35–45 parishes per district, this equates to 66–85 per cent of parishes returning gamekeepers in at least one census.Footnote 26 At the peak of gamekeeper numbers in 1911, about half the approximately 740 parishes in Norfolk returned gamekeepers, an observation that does not align with the comments of Thompson and Tapper that all of Norfolk was ‘keepered’.Footnote 27 The list of parishes in a district returning gamekeepers changed over time. In Swaffham, for example, gamekeepers were returned in twenty-three parishes in both the 1881 and 1911 censuses (Table 3), but between 1851 and 1921, a total of thirty-one parishes in Swaffham returned gamekeepers. In addition, the number of gamekeepers returned in a parish varied: Oxborough, in Swaffham, returned seven gamekeepers in 1851 but only one in 1911.

Table 3. Number of parishes with gamekeepers by registration district and census year

* Excludes King’s Lynn, Norwich, and Great Yarmouth.

In 1851, 214 parishes returned gamekeepers, but by 1881, this had increased to 318 parishes and to 366 by 1911, before dropping to 323 in 1921 (Table 3). In 1851, only Erpingham, Swaffham and Walsingham reported gamekeepers in twenty or more parishes, but by 1911, eleven districts returned gamekeepers in twenty or more parishes. Thetford was the only district that returned gamekeepers in fewer parishes in 1911 than in 1851, despite the fact that the number of gamekeepers doubled in this period (Tables 2 and 3), so growth here was due to an increase in the number of gamekeepers per parish. Flegg, which had the largest proportionate increase in gamekeeper numbers, also had the largest proportionate increase in parishes with gamekeepers, from two in 1851 to eleven in 1911. In Aylsham, the number of parishes returning gamekeepers doubled (Table 3), but the number of gamekeepers went up fivefold (Table 2). These examples demonstrate that growth in gamekeeper numbers in a district could result from an increase in the numbers of parishes with gamekeepers or in gamekeepers per parish or both. The high proportion of parishes returning gamekeepers to at least one census (see above) suggested that employment of gamekeepers had become widespread by 1911, even amongst owners of relatively modest estates, such as the 560 acres at Waxham for lease as a shooting estate in 1888.Footnote 28

In 1921, 323 parishes returned gamekeepers – including seven for the first time – just 12 per cent lower than in 1911. Four districts (Swaffham, Walsingham, Thetford, Wayland: Table 3) actually had more parishes with gamekeepers in 1921 than in 1911, even though the total number of gamekeepers in each district had declined (Table 2). All other districts showed a decline in the number of parishes returning gamekeepers, with Guiltcross and Blofield showing the greatest drop: they also had the greatest drop in numbers. As the average drop in the number of gamekeepers between 1911 and 1921 was around 40 per cent but the number of parishes with gamekeepers declined by only around 12 per cent, landowners were employing fewer gamekeepers. How much of this decline was due to economic factors, such as higher taxes, and how much was due to increases in efficiency and technology in game shooting are questions for investigation elsewhere.

Parishes returning larger numbers of gamekeepers

Although the average number of gamekeepers per parish increased from 1851 to 1911, parishes varied in the number of gamekeepers returned, but at all times, most parishes returned just one or two. The presence of many parishes with few gamekeepers makes it difficult to pick out trends in the numbers or locations of gamekeepers. In order to overcome this issue, this section focusses on parishes returning four or more gamekeepers to a single census return (high gamekeeper – HG – parishes). A small number of parishes returning particularly large numbers of gamekeepers (eight or more) to the 1911 census are also considered.

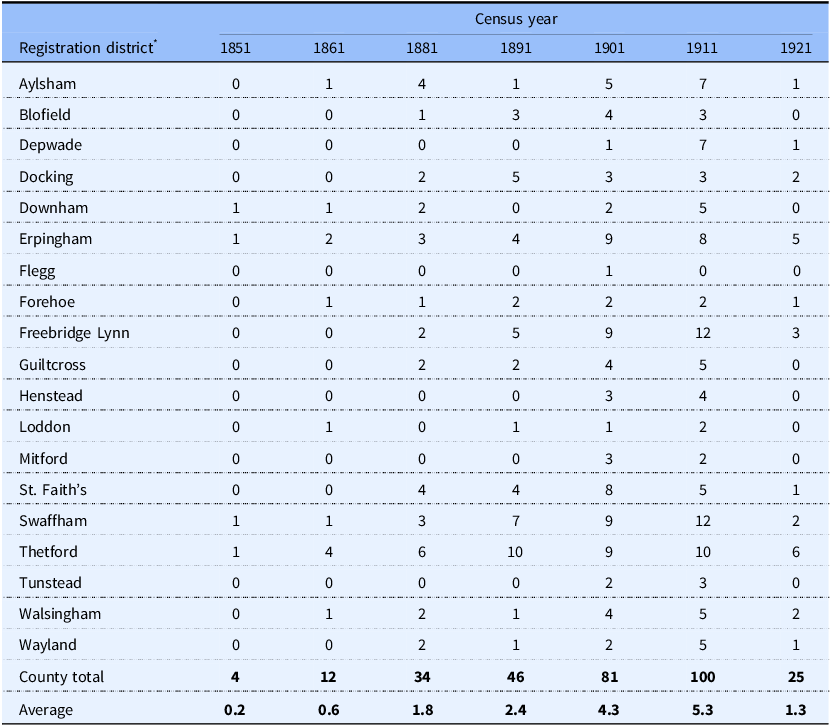

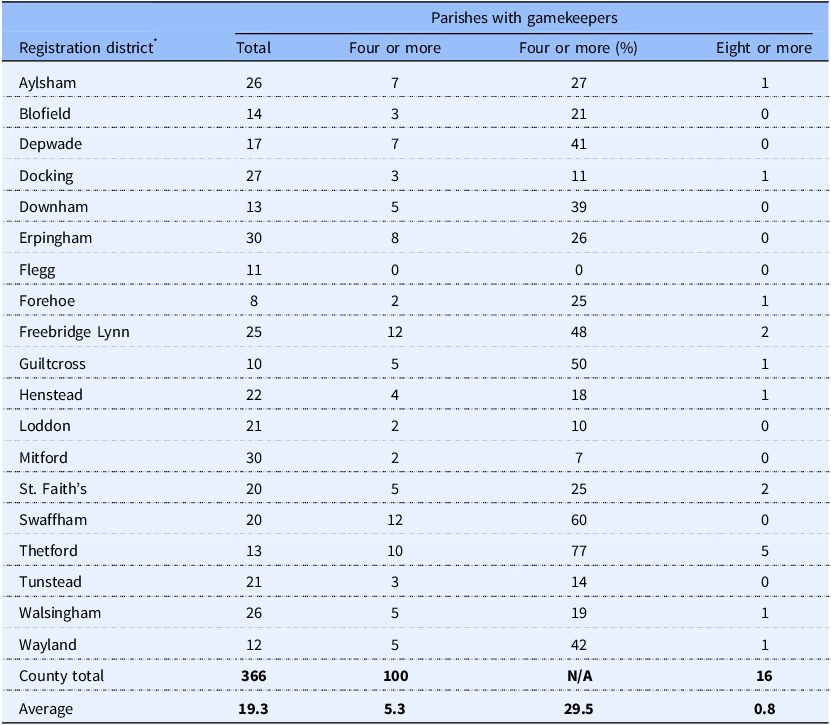

In 1851, there were just four HG parishes, but by 1911, this had risen to 100 with the greatest increase coming from 1891 to 1901 (35: Table 4). The average number of HG parishes in a district in 1911 was 5.3 with Freebridge Lynn, Swaffham, and Thetford having ten or more (Table 4): these districts also had high numbers of gamekeepers in 1911 (Table 2). Flegg had the fewest HG parishes, recording just one in 1901 and none in any other census. Of the six registration districts with seven or more HG parishes in 1911 (Table 4), only Depwade returned fewer than sixty gamekeepers (Table 2). The 100 HG parishes of 1911 formed two main groups divided by the per cent of HG parishes in 1911 and their geographic location. The first group (thirteen) had 27 per cent or fewer HG parishes and lay mostly in the east and centre of the county (Fig. 1 and Table 5). The remaining six had thirty-nine to 77 per cent HG parishes and lay in the west, in a crescent running from Freebridge Lynn to Depwade. The number of HG parishes had declined 75 per cent by 1921, to twenty-five (Table 4), and only ten of these were also HG parishes in 1911. Eight districts recorded no HG parishes in 1921, and only Erpingham and Thetford recorded more than four (Table 4). These observations are consistent with the suggestion above that landowners were generally employing fewer gamekeepers in 1921 than in 1911 although, as gamekeepers were still being returned from new parishes – there were five new HG parishes in 1921 – there was significant fluidity in employment patterns.

Table 4. Parishes with four or more gamekeepers by registration district and census year

* Excludes King’s Lynn, Norwich, and Great Yarmouth.

Table 5. Number of parishes recording gamekeepers in 1911, showing those with more than four and those with more than eight gamekeepers

* Excludes King’s Lynn, Norwich, and Great Yarmouth.

The landowners in HG parishes evidently had an interest in gamebird shooting, and many were presumably the seventy peers and great landowners with estates over 3,000 acres identified by Bateman in 1883.Footnote 29 As there were significantly more than seventy HG parishes in 1911, it’s likely that many owners of smaller estates – there were about forty of 2,000–3,000 acres – also employed at least four gamekeepers, possibly indicating some overstaffing.Footnote 30 Estimates suggest that a good head gamekeeper and two assistants could look after 3,000 acres or produce around 1,000 pheasants a year.Footnote 31

Amongst the 100 HG parishes in 1911, sixteen returned at least eight gamekeepers (Table 5), with the highest being eleven in Weeting All Saints (Thetford) and Illington (Wayland). Seven of these parishes were in the southwest (Fig. 1) with smaller groups in the north-west (four) and around Norwich (four), plus one outlier in Aylsham. These sixteen parishes, and the estates they represented, were diverse in area and gamekeeper employment patterns, as the following examples show. Hockwold cum Wilton (Thetford), where the estate (around 5,000 acres) was owned by the Newcome/Hardinge family, was the only parish to be an HG parish in every census, with four gamekeepers in 1851, eight in 1901, nine in 1911, and five in 1921.Footnote 32 Around Weeting All Saints (Thetford), the Angerstein family owned just over 7,000 acres, and in 1911, they employed ten gamekeepers, up from two in 1861, although numbers declined by 1921 (five). In Marlingford (Forehoe), there were ten gamekeepers in 1911, but unlike the examples above, numbers did not start to rise here until 1901 (five). Although Marlingford occupied just 617 acres, the main landowner (Rev. Evans-Lombe) owned 12,000–14,000 acres in total, suggesting that gamekeepers living here worked elsewhere.Footnote 33 The final example, Wolterton near Aylsham, owned by the Earl of Orford (Lord Walpole), returned ten gamekeepers in the 1911 census; however, before this, numbers ranged from zero to three, reflecting the fact that the house was unoccupied from the 1850s until the 1890s when the estate was let.Footnote 34 By 1921, there were only three gamekeepers at Wolterton suggesting a significant scaling back of game shooting after the First World War. These examples illustrate the influence of estate size and the shooting interests of the landholder on gamekeeper numbers.

Major employers of gamekeepers

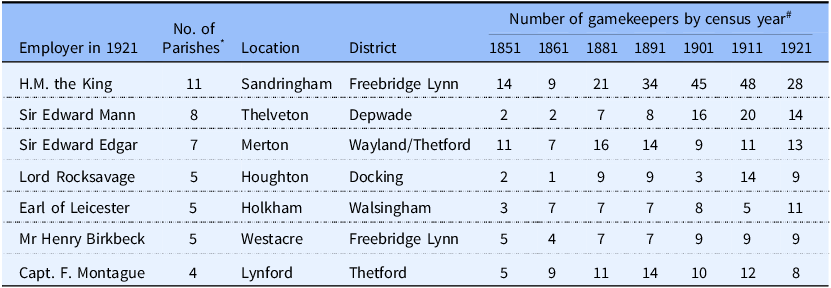

The analysis above examined parishes returning four or more gamekeepers to a census – and eight or more in 1911 – but large estates covering multiple parishes would have been hidden, particularly if their individual parishes housed fewer than four gamekeepers. For the first time in 1921, the name of the employer of each gamekeeper was recorded, allowing exploration of these large estates. Just seven landowners employed eight or more gamekeepers in 1921, and all owned estates covering multiple parishes (Fig. 1: Table 6). Adding together the number of gamekeepers in these parishes in previous census returns allowed the numbers employed in every census to be calculated (Table 6). Of the 100 HG parishes in 1911, six were linked to major employers (Table 6), but of these, only West Newton (part of the Sandringham estate) had eight or more gamekeepers. Geographically, five of the seven major employers were in west Norfolk (Fig. 1), a similar distribution to the HG parishes with eight or more gamekeepers. These seven estates had different patterns of ownership and trends in gamekeeper numbers, as the following examples show.

Table 6. Numbers of gamekeepers employed by major estates, 1851–1921

# The numbers are based on actual counts for 1921. For previous years, numbers for the same parishes were summed.

* The parishes in each estate are listed below. Those marked H were HG parishes in 1911. Where estates were sold or rented, the previous occupiers are stated.

H.M. the King: Anmer, Babingly, Castle Rising, Congham,H Dersingham, Flitcham with Appleton, North Wootton, Sandringham, Shernborne, West Newton,H Wolferton.

Sir Edward Mann: Billingford, Dickleburgh, Diss, Fritton, Larling, Scole, Thorpe Abbots,H Tivetshall St. Mary and St. Margaret.

Sir Edward Edgar (formerly Lord Walsingham): Griston, Little Cressingham, Merton, Stanford, Sturston, Thompson, Tottington.

Lord Rocksavage: Bircham Tofts, Great Bircham,H Harpley, Houghton, West Rudham.

Earl of Leicester: Egmere, Holkham, Warham St. Mary, Wells-next-the-Sea, Wighton.

Mr Henry Birkbeck (formerly the Hamond family): East Walton, Gayton Thorpe, Great Massingham, Pentney, West Acre.H

Capt. F. Montague (formerly Mrs Y Stephens): Cranwich, Lynford, Mundford,H West Tofts.

Four of the estates were owned by established elite families or were bought by them early in the period. The 20,000-acre Sandringham estate was purchased by the royal family (the future Edward VII) in 1862, for example, while the 16,000 plus acres of Lord Rocksavage (Marquis of Cholmondeley) at Houghton and the 43,000 acres of the Earls of Leicester at Holkham (Table 6) had been in their families for centuries.Footnote 35 The 12,000-acre Merton estate was owned by the Lords Walsingham but was rented to Sir Edward Edgar (Table 6) from the early 1900s.Footnote 36 By 1921, the remaining three large estates were owned by families whose money came from commerce, illustrating the growing influence of new money in elite society and their desire to emulate the landed gentry by buying country estates and taking up shooting. These included the Mann family who purchased Thelveton in 1867 and expanded their holdings subsequently using money from their brewing interests.Footnote 37 The banker Henry Birkbeck bought the 9,000-acre Westacre estate in 1897, while the 6,000–7,000-acre Lynford estate was occupied by a reclusive widow (Yolande Stephens) from 1862 to 1894 – her family money came from glass making – before it was eventually purchased by Captain Montague.Footnote 38

Along with differences in ownership, these major estates demonstrated varying patterns of changes in gamekeeper numbers, often correlated with changes in ownership or occupation, as the following examples show. At all dates, more gamekeepers were employed at Sandringham than at any other estate (Table 6). Just before its purchase by the royal family, there were nine gamekeepers and numbers rose steadily to almost fifty in 1911, greatly above the twenty-one needed based on the numbers suggested by Walsingham and Payne-Gallwey.Footnote 39 The gamekeepers at Sandringham were responsible for raising up to 12,000 pheasants a year, but there were only two weeks of shooting on the estate, again indicative of massive overstaffing.Footnote 40 The number of gamekeepers employed at Sandringham dropped in 1921 but was still twice that of any other estate.

Gamekeeper numbers at Thelveton also reflected changes in ownership. There were very few gamekeepers before its purchase by the Mann family in 1867, after which numbers grew to twenty in 1911 (Table 6). Thomas Mann died in 1886, so much of the increase was driven by his son, Edward, who was much more of a socialite.Footnote 41 At Merton, gamekeeper numbers reflected financial issues. Numbers were high from 1881 to 1891 (14–16) but dropped in 1901 before rising again by 1921 (13; Table 6). The sixth Lord Walsingham, owner during much of this period, was a renowned shot who hunted with the Prince of Wales, amongst others, and wrote books on shooting.Footnote 42 Although very wealthy when he inherited, his enthusiasm for shooting, coupled with corruption by some of his agents, resulted in his bankruptcy in the early 1900s and the letting of the Merton estate.Footnote 43 The changes in gamekeeper numbers presumably reflect these money issues and the investments of tenant Sir Edward Edgar.

Holkham Hall, home to the Earls of Leicester, was renowned for innovations in game rearing and shooting and was the only major employer on the north-Norfolk coast (Fig. 1).Footnote 44 It was the only estate where gamekeeper numbers were higher in 1921 than in 1911, but there were always relatively few gamekeepers for its size and prestige (Table 6). It is possible that gamekeepers for Holkham had previously lived in nearby parishes that returned no gamekeepers in 1921, such as Burnham Overy, Quarles, and South Creake. If the ten gamekeepers in these three parishes in 1911 were added to the five calculated (Table 6) that would give fifteen, which would be higher than the 1921 number and close to the estimate of Walsingham and Payne-Gallwey, assuming only half of Holkham was shot (21,000 acres).Footnote 45 Westacre showed a much more stable level of gamekeepers than the other examples. Here, the number of gamekeepers plateaued from 1901 to 1921, having increased slightly when Henry Birkbeck purchased the estate in 1897 from the Hamond family.Footnote 46 Gamekeeper numbers on the final major estate, that of Lord Rocksavage at Houghton, showed two distinct peaks (1881/1891 and 1911) on either side of a large drop in 1901 (Table 6). This decline is not at the same time as Lord Rocksavage was reported as intending to sell the entire Houghton estate (1885–1889), something that did not happen as his descendants still own it, and the cause of the decline is unclear.Footnote 47

Gamekeepers and poaching: 1857–1862

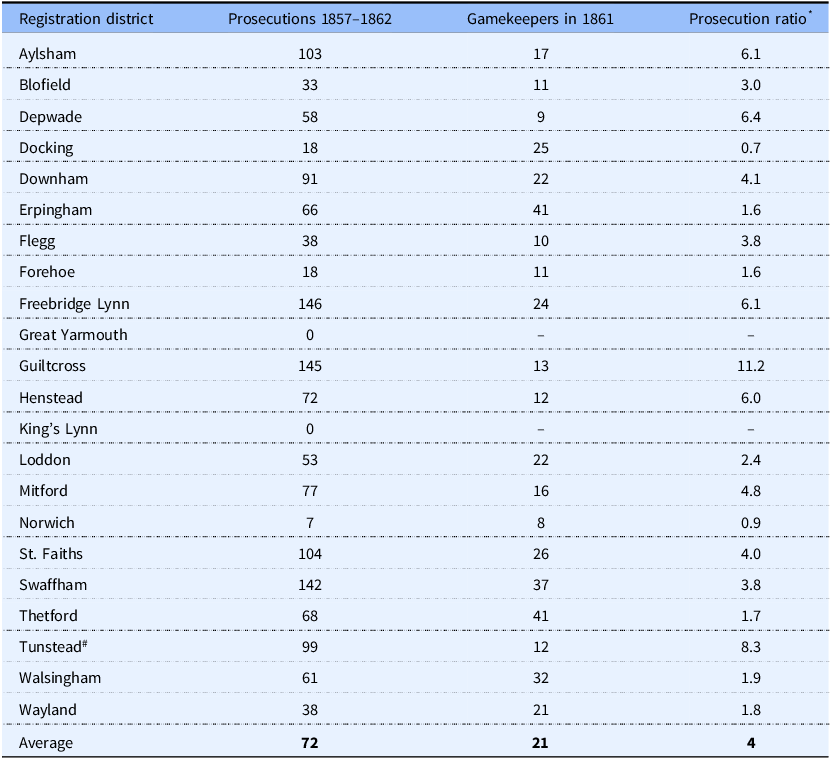

The landowners’ interest in gamebird shooting influenced gamekeeper employment, but numbers might also have been influenced by poaching, either to deter a known poaching threat or to ensure poaching did not become an issue. Most poaching prosecution statistics are at the county level, but one return included district data (1857–1862), including the parish in which the offence took place.Footnote 48 Using these data, for this short period, correlations between gamekeeper numbers and poaching prosecutions can be explored, as well as other factors such as the seasonality of poaching and the prevalence of poaching gangs. There were 1,437 poaching prosecutions – not all resulted in conviction – in Norfolk between 1857 and 1862, almost 240 per year (Table 7), although prosecutions had declined to 121 in 1911.Footnote 49

Table 7. Poaching prosecutions (1857–1862), gamekeeper numbers (1861), and prosecution ratios by registration district

* Prosecution ratio is the number of prosecutions from 1857 to 1862, divided by the number of gamekeepers returned to the 1861 census.

# Some areas of Thetford did not make a return, so numbers here are likely to be an underestimate.

The police, like gamekeepers, were able to arrest poachers, but there were few policemen in rural Norfolk: in 1861, the county force was only 221 men, of whom 149 were based in Norwich, Kings Lynn, and Yarmouth.Footnote 50 Since there were at least three times as many gamekeepers as policemen, and gamekeepers were far more likely to be in the same locations as poachers, the following discussions assume that the gamekeepers (and their employers) were the main instigators of poaching prosecutions. It was not until the 1862 Poaching Prevention Act – right at the end of the studied period – that the police were brought fully into the fight against poaching as this act allowed them to stop and search suspects in any public place.Footnote 51 It should also be recognised that prosecutions represent just the tip of a very large iceberg of poaching.Footnote 52 Many, if not most, poachers were not caught or if they were, might be fined, sacked, or evicted rather than being prosecuted since the landowner was often their landlord and employer.Footnote 53

Poaching prosecutions were not spread evenly across Norfolk, but there was no obvious geographical grouping of districts with high or low prosecutions (Table 7: Fig. 1). There were large differences in prosecution levels with five districts recording over 100 cases and several under 20. Areas with more gamekeepers did not necessarily have more prosecutions: Erpingham and Thetford both returned forty-one gamekeepers in 1861 but had below-average prosecutions and prosecution ratios, while Freebridge Lynn and Guiltcross had high prosecutions and above-average prosecution ratios, but average or low gamekeeper numbers (Table 7). (The Sandringham estate was bought by the royal family in 1862, so their presence was not a factor in the high level of prosecutions in Freebridge Lynn.) The parishes of Old Buckenham, Kenninghall, and Quidenham accounted for 50 of the 145 prosecutions in Guiltcross despite the fact that together they returned only one gamekeeper to the 1861 census: Quidenham was a well-known partridge estate later in the century.Footnote 54 The estates in these parishes in the north of Guiltcross were owned by the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Albemarle, so perhaps these landowners were keen to ensure poachers were detected and prosecuted by, for example, hiring night watchers or moving gamekeepers from other areas.Footnote 55

Archer reported that, in the early 1860s, there were increased levels of incendiarism along the Norfolk/Suffolk border, although levels were much lower than in the 1830s and 1840s, and many of those arrested for arson also had poaching convictions.Footnote 56 In 1861, there were just four gamekeepers in the eight Norfolk parishes mentioned by Archer as having a heavy concentration of arson attacks, albeit over a much longer timeframe. Of the eight, five had no poaching convictions between 1858 and 1682, with the remaining three having fifteen between them, but all were in different districts (Thetford, Guiltcross, and Wayland).Footnote 57 There was thus no evidence for colocation of poaching, gamekeepers, and arson attacks between 1857 and 1862, suggesting that factors such as deprivation were more important.

Osborne and Winstanley demonstrated that poaching increased around large towns in northern England while Muge identified poaching clusters around Derby and the coalfields of south Derbyshire and north Leicestershire, and Archer identified clusters around urban centres in Lancashire.Footnote 58 Was there more poaching near urban areas in Norfolk during this period? Blofield, bordering Norwich and Great Yarmouth, had below-average prosecutions (Fig. 1: Table 7), as did Forehoe, which borders Norwich, and Flegg, which borders Great Yarmouth. In contrast, Freebridge Lynn and Downham, which border King’s Lynn, and St. Faiths next to Norwich, had higher-than-average prosecutions. Thus, there was little evidence for higher levels of poaching activity around urban areas. There was also no obvious correlation between the numbers of gamekeepers in a district and the level of prosecutions that might suggest that the presence of gamekeepers deterred poachers or resulted in a higher level of prosecutions, indicating a complex interplay between gamekeeping and poaching during this period, as has been suggested elsewhere.Footnote 59

Howkins noted that, in Oxford, most poaching activity took place in the autumn and winter months, when employment was lowest and food scarcest and the number of gamebirds (and rabbits) was highest: Osborne reported similar findings in Suffolk.Footnote 60 In Carter’s extract of cases from the Norfolk Chronicle (January 1857–December 1860), 32 per cent of cases were heard in December and January and 60 per cent between November and March.Footnote 61 Allowing for a short gap between apprehension and prosecution, peak poaching activity was in the autumn and winter, as in Oxford and Suffolk. Howkins showed that around Oxford, most poachers travelled only short distances, and this seems also to be the case in Norfolk: of the approximately fifty men for whom a home parish was mentioned by Carter, the vast majority lived close to where they transgressed.Footnote 62 Most of those prosecuted were (agricultural) labourers, as noted by Howkins.Footnote 63 Agricultural wages in Norfolk were around the national average in the 1860s, although this does not mean that a family could live on these, especially in winter.Footnote 64 The amount of casual labour available in this season would vary across districts, which might influence the level of poaching. November was also the peak month for arson attacks, which Archer suggested was linked to the lower wages and reduced work at this time of year.Footnote 65 Thus, there may well be a link between the level of poaching activity and wages, rather than with the presence of gamekeepers.

Archer found significant evidence for (at times violent) poaching gangs (four plus individuals) from urban Lancashire in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and John Dunne (head of Norfolk police) asserted that in the early 1850s, there were several gangs in Norfolk and Suffolk.Footnote 66 Carter identified one relevant instance at Brogdale in 1858, involving eight men, but in his list of poaching prosecutions (from a different source to those on gangs so not directly comparable), the largest group was three.Footnote 67 The Parliamentary returns for some districts broke prosecutions down by year and parish, which allowed the identification of thirteen possible gang prosecutions, none in urban areas. These thirteen prosecutions were spread across the county, with Swaffham having four and St. Faith’s three, with the remainder in Erpingham, Guiltcross, Henstead, and Thetford. The largest case was eight individuals in Swaffham in 1861, well short of the up to twenty recorded by Archer or the approximately twenty-five in Costessey (Forehoe) in 1823.Footnote 68 The sixty-five individuals prosecuted in these groups represented around 10 per cent of the 597 poaching prosecutions in these districts (Table 7) suggesting that gang poaching was not common in this period. Thus, in Norfolk at this time, poaching occurred in all the rural districts, with no obvious geographical concentrations around urban areas and little evidence for significant gang activity. Most poachers were unskilled labourers on relatively low wages, who presumably took to poaching close to their home parish when work was scarce and game more abundant, irrespective of the presence or absence of gamekeepers.

The influence of geology and agricultural economics

Although HG parishes with four to seven gamekeepers were spread widely across the county, the same was not true for the HG parishes with eight or more gamekeepers or for the estates of major employers, both of which were concentrated in the west of the county (Fig. 1). This section investigates the influence of geology and agricultural economics on the uneven distribution of these twenty-two examples (sixteen plus seven, minus one that is in both groups).

Geologically, Norfolk has been divided into eight main soil types including sandy acidic soils, more fertile clay and loam, and wet marshy regions (Fig. 2).Footnote 69 Many of the examples (ten of twenty-two) lay in Breckland or on its borders (Figs. 1 and 2), where much of the land was reclaimed or enclosed in the latter half of the eighteenth century and the consolidation of smaller farms into larger estates was apparent by Faden’s 1797 map of Norfolk.Footnote 70 In this relatively unproductive region, small-scale agriculture was uneconomic, even when the corn price was high, and since the land was inexpensive, large arable estates developed.Footnote 71 The Northwest Norfolk ‘good sands’ region around Freebridge Lynn (six of the twenty-two), was characterised by acidic, sandy upland heaths that had been enclosed and significantly improved in the mid-1700s.Footnote 72 Large and medium-sized estates came to dominate here, as in Breckland, with agriculture relying on cheap labour and high grain prices for economic viability.Footnote 73 In the Northern Heathland and dissected clays around Norwich (four examples: Figs. 1 and 2), smaller estates dominated on the richer soils, catering to prosperous Norwich-based gentry and merchants rather than to the landed elite.Footnote 74 The coastal Northern Heathlands were less productive with more acidic soils than the areas close to Norwich, and the estate of one major employer (Earl of Leicester: Holkham) and one parish with ten gamekeepers in 1911 (Lord Walpole: Wolterton) were situated on these poorer soils.Footnote 75 Setting aside the four estates around Norwich, which could be considered a special case, eighteen of the examples were in regions of sandy or acidic soils, where land prices were relatively low, and agriculture was only profitable on a large scale and when corn prices were high. In addition, these regions provide habitat that is well-suited to pheasant and partridge.

Figure 2. Norfolk soil types.

Based on Susanna Wade Martins and Tom Williamson, Roots of Change: Farming and the Landscape in East Anglia, c.1700–1870 (Exeter, 1999), p. x.

The agricultural depression, which began around 1879 driven by cheap corn from America and Russia, caused a collapse in grain and land prices, giving impetus to the development of estates for game shooting.Footnote 76 Farm rents on marginal lands, such as Breckland, dropped by half in many areas, putting pressure on the landowner to sell or find alternative sources of income.Footnote 77 Further pressure on estate income came from the mortgage costs (from loans taken out when land and corn prices were high), the financial burden of bequests and annuities, and increases in inheritance and income tax.Footnote 78 Landowners needed to ensure that the land remained in cultivation as a game, especially partridges, would not stay on uncultivated land, and some set extremely low rents to encourage tenants. In areas such as Breckland, estates still sold at a good price but for their shooting potential, rather than agricultural value.Footnote 79 Some income might be raised from selling the shot game, but this would not cover the full cost of rearing and preserving the gamebirds.Footnote 80 Those with income from other sources, such as the rent of properties in the developing cities or industry and commerce, might have the funds to retain shooting estates for their own use, such as Sir Edward Mann at Thelveton. Others, when circumstances dictated, sold or let their estates to shooting tenants or consortia, often to those with ‘new money’, such as at Merton and Westacre. Many landowners had more than one estate, such as Lord Walpole at Wolterton, and would reduce their expenses by living elsewhere and letting good estates to a shooting tenant who would bear much of the expense.Footnote 81

Although this discussion has focussed on twenty-two examples of larger shooting estates, the development of shooting in other regions of Norfolk also appears to have been influenced by geology and agricultural economics, but with different results, as the following examples show. In Forehoe and Depwade, (Figs. 1 and 2), there were relatively few gamekeepers or HG parishes as the fertile Central Clayland soils made land relatively expensive and smaller farms profitable, particularly for pasture.Footnote 82 The densely settled Broadlands (Tunstead) in the Flegg loams also had few large estates, almost no HG parishes, and relatively few gamekeepers as wildfowling was preferred to labour-intensive pheasant rearing.Footnote 83 Gamekeepers here often had broadly based roles: in Hoveton (Tunstead), for example, William Hewitt – gamekeeper from 1859 to 1878 – was also the keeper of the gull colony, marshman, and wildfowler.Footnote 84 Thus, the parishes employing most gamekeepers and the estates of the largest employers lay in areas with poor soils, and the development of these estates for shooting was influenced by geology and agricultural economics.

Fashion, access, and game shooting

The importance of the Victorian and Edwardian shooting party to the elite and, in particular, the role of the future Edward VII in its development as a fashionable pastime has been discussed previously, and several reasons that gamebird shooting became so popular have been identified.Footnote 85 These included social exclusivity (male, upper classes only) and privacy: shooting took place on private estates hidden from public view, unlike fox hunting.Footnote 86 Other reasons for its popularity included the timing – the shooting season occurred after the racing and yachting seasons – and technical improvements in guns, bird rearing, and the introduction of the battue and beating.Footnote 87 The shooting party became a competitive sport that required some skill, and participation could open doors into the higher levels of society with a payoff in status and influence.Footnote 88

Norfolk and Suffolk became highly fashionable areas for shooting throughout this period, and, as Everitt observed, no other counties could compare to them for pheasant and partridge shooting. The best lands were along the Norfolk/Suffolk border, the location of many of the examples discussed here (Fig. 1).Footnote 89 The area around Freebridge Lynn also had several major shooting estates, including Sandringham where the top shots of the day regularly congregated thanks to its royal owners.Footnote 90 Although the countryside was suitable for gamebirds, Norfolk’s good railway network was important also, with day or weekend trips to major estates possible on the lines from London to Kings Lynn, Norwich, and Thetford, aided by luxurious shooting specials run by enterprising railways companies.Footnote 91 Access to Sandringham was facilitated by the purpose-built station at Wolferton.Footnote 92 The importance of access is demonstrated by newspaper advertisements such as one in the Eastern Daily Press for a 4,000–6,000 acre estate no more than 3 hours from London, with good amounts of pheasant and partridge.Footnote 93 The short distances between the main shooting estates also aided popularity as shooting parties could shoot multiple estates on one visit, as in 1873 when Edward VII shot at Elveden in Suffolk (near Thetford) before shooting at Sandringham.Footnote 94 The popularity of shooting was underlined by the large number of advertisements for shooting estates to let or wanted and the many reports of shooting parties, appearing in the Norfolk newspapers from the 1870s onwards.Footnote 95 Thus, fashion and ease of access were important in securing Norfolk’s popularity amongst elite shooting parties, although this would not have come about without the suitability of the underlying geology and the development of large estates.

Conclusions

This is the first examination of gamekeeper numbers within a county and highlights the wide variation between registration districts, which could be as different from each other as Norfolk was from Devon or Lancashire.Footnote 96 From 1851 to 1911, gamekeeper numbers in Norfolk increased from 319 to 1030, before halving by 1921. Some districts showed consistent growth in numbers, while others showed fluctuations, although culminating in an overall increase. Increases in gamekeeper numbers in a district came from increases in the number of gamekeepers per parish and in parishes with gamekeepers. Gamekeepers were not evenly distributed between the districts, with higher numbers in districts to the west of the county where soils were sandy and acidic. Despite the high numbers of gamekeepers, on all dates, most parishes had only one or two, and many had none, so the density of gamekeepers never reached the levels suggested by Tompson and Tapper of three or four per parish.Footnote 97 The high number of parishes returning gamekeepers implies that owners (or tenants) of even relatively modest estates would employ a gamekeeper to provide shooting for friends and relatives.

The number of prosecutions for poaching (1857–1862) varied greatly across the registration districts, but there was little evidence that local gamekeeper’ numbers or proximity to major population centres affected prosecution rates. Most poachers worked locally alone or in small groups, with limited evidence for gangs, and were most active in the autumn and winter. Limiting or deterring poaching seems to have been only a minor driver for the employment of gamekeepers, with game rearing, organisation of shoots, and vermin destruction more important.

There were 100 parishes with four or more gamekeepers by 1911, with some in every district. However, parishes with eight plus gamekeepers in 1911 were concentrated in areas with sandy soils of low agricultural quality, as were the estates of the landowners employing most gamekeepers in 1921. The growing influence of ‘new’ money was visible, as the nouveau riche used money from commerce to buy or rent estates from the cash-strapped landed gentry. The concentration of major shooting estates in the west of Norfolk reflects the influence of geology and agricultural economics on the earlier development of large estates, which were already owned by the elite and well positioned to become shooting estates. Fashion and patronage – particularly royal patronage – were important to the development of shooting estates, with the shooting party used to develop and cement social and political ties. Thus, geology, agricultural history, economics, and fashion combined to drive the development of Norfolk as a fashionable shooting county resulting in the increasing employment of gamekeepers. Poaching seems to have had little influence on gamekeeper numbers, at least in the period studied.

The level of influence of these factors will differ in other counties with, for example, poaching and agricultural wage levels apparently affecting gamekeeper numbers in ways that seem not to apply here.Footnote 98 Detailed analyses of other counties, similar to those carried out here, would allow a more nuanced picture of changes in the numbers and location of gamekeepers during the high period of shooting and of the importance of different factors in driving these changes.

Competing interests

The author declares none.