1. INTRODUCTION: CHALLENGING EUROCENTRIC VIEWS OF QING CHINA IN THE NEW GLOBAL HISTORY

This article intends to show how recent works on global history, mainly those attempting to compare the paths of economic growth between China and Europe in the framework of the great divergence debate, have fallen into the trap of dealing with large geographic units (i.e. unspecified regions of China or Europe) and macro-economic indicators such as GPD per capita, which do not really apply for early modern economies (Madisson Reference Madisson2007). In addition, unreliable data have been used to measure China's real wages (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Bassino, Ma, Moll-Murata and Van Zanden2011; Allen Reference Allen2015)Footnote 1. The progressive market integration in European, American and Asian regions does not only apply to the price convergence that some economic historians (O'Rourke and Williamson Reference O'Rourke and Williamson2004, p. 109) have observed, and consequently the origins of globalisation have been analysed in economic terms rather than in a more multidisciplinary context observing socio-economic, cultural and political dynamics (Flynn and Giraldez Reference Flynn and Giraldez2008).

Market integration and globalisation also occurred through the circulation of goods, transforming patterns of consumption, as well creating global trade networks during the 18th century. Consumption, long-distance business partnerships and the creation of trans-national trade alliances based on trust favoured an economic system that went beyond official institutions and the state capacity to manage economic resources. The main novel contribution of this paper is that it cross-references European and Chinese sources, presenting new empirical evidence and implementing a new case study—that of Marseille and Macao as strategic entrepôts for international trade in 18th-century Europe and China. The aim is to renew the field of global history in China and Europe and to show, at a micro-scale, the «footprints» (Ma and Yuan Reference Ma and Yuan2016) of the great divergence debate by analysing how local trade changed consumer behaviour in specific localities of China (mainly the Macao-Canton trade axis) and Western Mediterranean Europe (through the Marseille-Seville-Cadiz trade axis).

A recent debate between Drayton and Motadel, on the one hand, and Bell and Adelman, on the other (Bell Reference Bell2014; Adelman Reference Adelman2017; Drayton and Motadel Reference Drayton and Motadel2018) showed that even though they reach no consensus, they do share points of agreement, particularly in acknowledging that the new global history can be implemented through the reduction of scales in geographic and chronological units of comparisons with more case studies. This advance in practice can be achieved through the so-called jeux des echelles (Revel Reference Revel1996), that is cross-referencing historical sources, in which regions, villages, nations, institutions, trade companies, social actors, family groups, etc. can be better analysed and compared. The case study of the Roux company in Marseille and the Grill company in Macao and Canton, for the introduction of Chinese and European goods in both markets, serves as an example of how the global process is influenced by local socio-economic forces. Such an example underscores the relevance of the task of progressively renewing the field of global history.

The circulation of global goods transforming consumer behaviour, the introduction of European wines and liquors in Macao-Canton and the introduction of Chinese goods (silk and porcelains) in Marseille-Seville, reveal the micro-foundations of globalisation on a local basis. Such globalisation occurred through the circulation and exchanges of goods, suggesting, therefore, that early globalisation took place much earlier than 1820—as O'Rourke and Williamson argued (Reference O'Rourke and Williamson2004, p. 111). Economists stress price convergence as the main measure of market integration for modern-era markets (O'Rourke and Williamson Reference O'Rourke and Williamson2004; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Bassino, Ma, Moll-Murata and Van Zanden2011; Broadberry et al. Reference Broadberry, Guan and Li2017), whereas early modern historians (Riello and Roy Reference Riello, Roy, Roy and Riello2018) pay attention to socio-cultural and political causes, especially given that we are dealing with the complex economy of Qing China. These approaches might be complementary. Therefore, as Flynn and Giraldez (Reference Flynn and Giraldez2008, p. 361) argue «it is a grave error to restrict conceptualization of globalization to the sphere of economics alone, since global economic forces have evolved in a deep and intimate intermix with noneconomic global forces over the past five centuries».

Such complementary analysis of market integration is in line with the approach of this article, which challenges the Eurocentric focus of some scholarship in recent decades dealing with comparisons between Western regions and their Asian counterparts. Such Eurocentric views (Jones Reference Jones1981; Landes Reference Landes1998; Duchesne Reference Duchesne2011; Vries Reference Vries2015; Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2018) have launched attacks against China's Confucian beliefs, institutions and rationale of private entrepreneurship outside the officialdom (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2018), as well as observing the global movements of goods and economic transformation only in terms of the British Empire, which has led to an «Anglo-centric» scholarship exceptionalism (Brewer Reference Brewer2005). Thus, this paper also presents a general overview of how global (economic) history and studies on consumption have been influenced by such Eurocentric (or «Anglo-centric») views, and how such scholarship has paid only marginal attention to American marketsFootnote 2, mainly the role of the Manila galleons, in this global market integration.

The California School (Von Glahn Reference Von Glahn1996; Marks Reference Marks1997; Wong Reference Wong1997; Frank Reference Frank1998; Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2000; Goldstone Reference Goldstone2008; Flynn and Giraldez 1996) places the emphasis on the economic development of East Asian regions, mainly China, to challenge the above-mentioned Eurocentrism. Their major focus was to re-write the history of China by exploring why after so many centuries of leadership, since the Song dynasty (Needham Reference Needham1956, pp. 543–82), modern science and capitalism had not emerged in the Middle Kingdom. Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2000) emphasised the role played by the Americas providing Europe, mainly the most advanced areas of North-western Europe (Great Britain and the Netherlands), with energy sources and raw materials to achieve the early stages of the first Industrial Revolution. European regions were thus «lucky» (Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2000) to have found the Americas as this allowed Europe to obtain the necessary resources for modern economic development while China was left behind at the dawn of the 19th century.

Analysing national narratives, either Eurocentric or Sinocentric, as well as locating core economic centres seems paramount to observe the world economic system as a polycentric space (Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018). Few studies dealing with comparisons between China and Europe have escaped the Eurocentric or Sinocentric bias (Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2000; Elvin Reference Elvin2004; Hamashita Reference Hamashita2015). To overcome any sort of -ism that is commonly marked by a revival of national narratives (Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018) is the great challenge for new global history studies. It is relevant to continue the line of research opened by the above-mentioned pioneering historians who have called for comparisons between European regions and their East Asian counterparts by focusing on changes in household consumer behaviour and how the introduction of overseas goods transformed regional economies, as well socio-cultural habits, tastes and fashions.

Regrettably, studies focusing on Mediterranean regions and their connections (nodes of trade and consumption) with the Atlantic and Asian world have been consigned to a lower status in the historiography. Long-distance partnerships, transnational trade networks and the circulation of overseas goods during the 17th and 18th centuries dynamised the local economies of both South China (through the axis Macao-Canton) and Western Mediterranean Europe (through the Marseille-Seville-Cadiz axis). The nodes and socio-economic linchpins of trade and consumer regions connecting China, the Americas and Europe have received only marginal attention in global (economic) history. In recent years some works have dealt with such connections, yet comparative history is still partly neglected. Studies dealing with Iberian empires, regional cases for the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas or Pacific, although scarce and insufficient when compared with studies dealing with North-western European regions, are on the rise however (Bonialian Reference Bonialian2012; Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia2013; Hausberger and Ibarra Reference Hausberger and Ibarra2014; de Sousa Reference De Sousa2018; Marichal Reference Marichal, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018; Yun-Casalilla Reference Yun-Casalilla2019).

The weak state capacity of the Qing empire to collect taxes efficiently and manage investments in the different provinces of China, as well as the creation of a huge, and under-paid, bureaucracy, meant that the economy became dependent on foreign trade (American silver) and private entrepreneurship which created an «unofficial» system that was very difficult to control and very easy to corrupt (Deng Reference Deng1999; Menegon Reference Menegon2017; Perdue Reference Perdue2017). The findings of this paper mainly point to the latter factor. The high amount of American silver being accumulated by private local Chinese merchants of Guangdong and Fujian provinces, and the intermediation and business alliances between local officials, the Hùbù 户部 or popularly known as Hoppos (Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2011, pp. 7-9), Hong merchants, and foreign traders and companies settled in Macao and Canton during the 18th century, will shed light on the Chinese local traders. Such trade networks fostered the demand in South China for European goods (wines, liquors, clocks), American cropsFootnote 3, and the exchange of Chinese goods (silk, tea and porcelain) for American silver.

This research will show the highly profitable business in the hands of the governors of Guangdong and Fujian provinces, as well as the Hoppos and Hong merchants driving a huge interest in exchanging such commodities with Western traders as well as high-interest rates for business loans. These interest rates helped line the pockets of merchants and officials who managed to evade the control of the central government in Beijing. The new historical evidence provided in this paper from the Arquivo Historico de Macau (the private correspondence of the Swedish Grill Company established in Macao and Canton), Archive de la Chambre de Commerce de Marseille, as well as trade records from the Archivo General de Indias de Sevilla, when the Qing dynasty established the Canton System yīkǒu tōngshāng一口通商 (Liang Reference Liang1999), will offer a new perspective on the state vs. local merchants in mid-Qing China, and changes in consumer behaviour prompted by local merchants. Ultimately, such a case study might reveal the drivers of Chinese trade, the functioning of European and Chinese trade nodes, and the economic apparatus beyond the control of the Qing state bureaucracy.

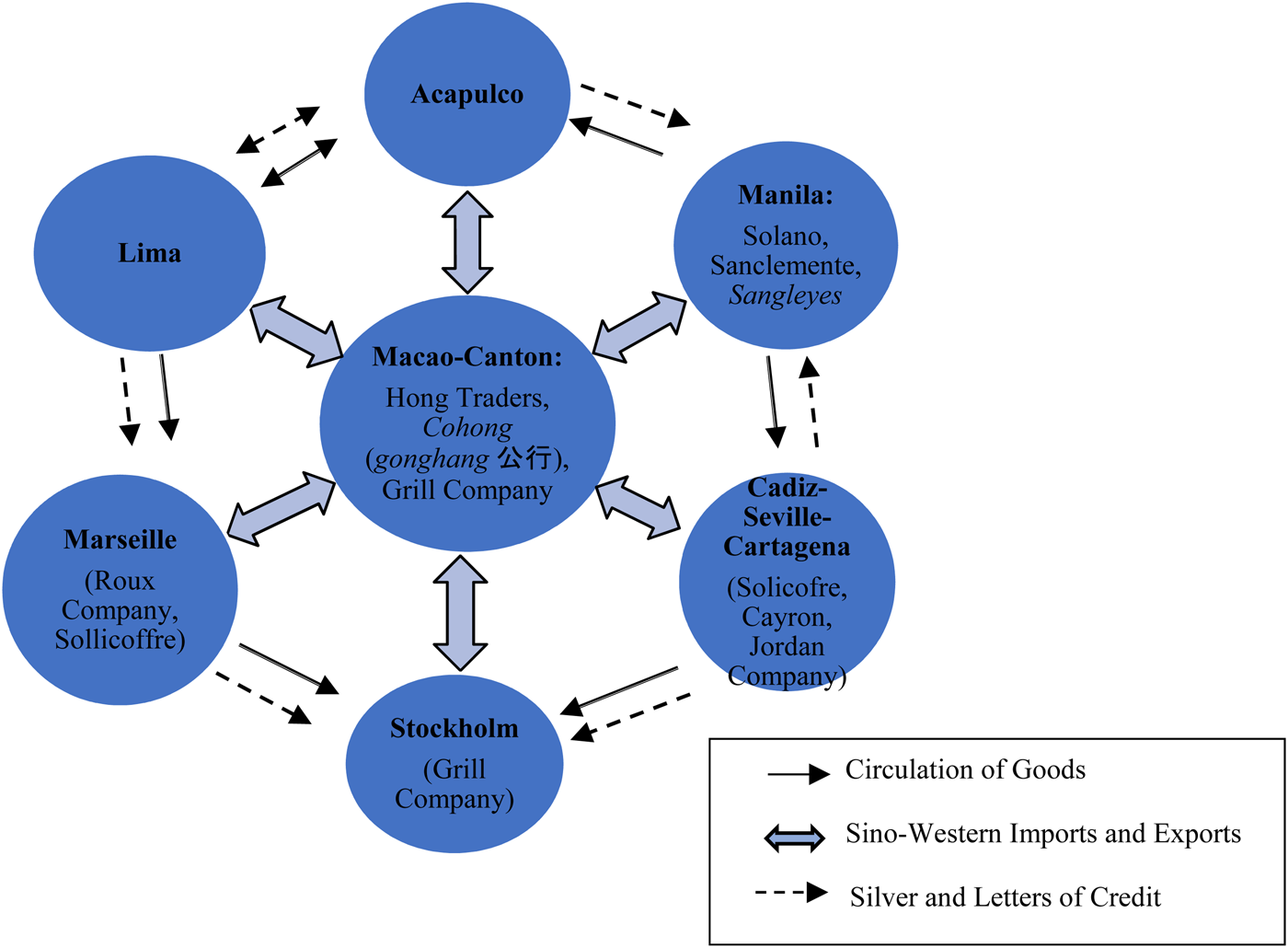

The Grill Company, established in Macao-Canton, worked predominantly with Hong merchants of Canton, as well as the main trade company that controlled the Mediterranean market during the 18th century, the Roux Company of Marseille. Through such connections we can unveil the business links that both companies had in South China, as well as along the trade routes of the Spanish empire such as Manila-Acapulco, Callao-Lima-Buenos Aires (Ibarra and del Valle Pavon Reference Ibarra and Del Valle Pavon2017) and Cadiz-Seville, which were the main points of entry for Asian goods in Europe integrating the Pacific and Atlantic markets. This demonstrates the complexity of Sino-European trade networks, mainly those operating in the Mediterranean and South China (Macao-Canton) markets, which were shaped by the social components of the network based on family and co-national relations, the spatial mutation of the network and its transformation according to the space and environment they operated in, and the coalition of groups based on internal organisation and inter-group relations to maintain socio-economic status and power. Thus, the main focus of the case study is on: (1) how the process of economic change took place in regions of South China and Europe through the strategic location of the main port cities such as Macao and Marseille; (2) the degree of such economic transformation through the trade networks connecting Marseille and the areas of the Western Mediterranean to Macao and Canton to exchange goods; (3) how long-distance partnerships and alliances between the elites and traders of South China and Western Mediterranean regions managed to bypass official institutions.

2. THE DISTRIBUTION AND CONSUMPTION OF CHINESE SILK AND PORCELAIN IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN: MACAO AND MARSEILLE AS A CASE STUDY FOR NEW GLOBAL HISTORY

The comparison between Macao and Marseille is relevant due to their strategic nature and locations as transnational territories that stimulated the economies of South China and Western Mediterranean regions by hosting communities of diverse ethnic origin and culture, as well as becoming global trade hubs for the circulation of overseas goods and American silver. This fact contributed to the relocation of trade houses and long-distance partnerships in the Pacific market, with South China (Macao-Canton) as the main node, as well as Western Mediterranean Europe (Cadiz-Seville-Marseille) as a geostrategic location to control the market and demand for Chinese goods in Europe.

The late 17th century, and especially the 18th century, seems to be a crucial period for understanding how the demand for overseas goods was evolving through shifts in economic indicators such as levels of income of different socio-professional groups, as well as demand and consumer choices. Establishing typologies of goods is crucial to show how such items penetrated social strata with different levels of wealth, and to understand social relations between suppliers and consumers. The networks of distribution and the creation of new needs in consumers are factors that need to be further analysed to understand how traders and consumers circumvented state policies governing consumption and trade, especially protectionist policies, and how they fostered the demand for overseas goods in different periods. Within the socio-economic changes of Ancien Regime Mediterranean Europe, with the arrival of the new Bourbon dynasty to the Spanish crown, and the Qing reign of Kangxi 康熙 (1661–1722), Yongzheng 雍正 (1723-1735) and Qianlong 乾隆 (1736-1795), the period known as the «Prosperous Era of Kangxi and Qianlong» or «High Qing» (Rowe Reference Rowe2009, p. 63), it seems relevant to consider the extent to which such prosperity and the relative stability of Mediterranean trade after the end of the Spanish Succession War created a favourable framework for economic growth through global trade.

Special emphasis is placed on the transformation of tastes and fashions, as well as new lifestyles, through the introduction of durable and semi-durable goods, and how local tradition and habits were challenged by the consumption of such goods. The major trade groups that settled in Marseille, such as the Roux-Frères, the Grill Company and their alliances with local traders of Canton and Macao, stimulated trade and the circulation of goods in the Western Mediterranean and South China during the 18th century. From Western to Levantine regions of the Mediterranean, the Roux-Fréres Company established trade houses throughout the Mediterranean basin, especially in areas of the Near East such as Alexandria, Aleppo, Tripoli, Damascus, Acre and Cairo, connecting with the nodes of the Silk Road (see map 1). Figure 1 shows the Chinese manufactures made of silk (stockings) that were re-exported from Marseille to Mediterranean Spain, mainly to the ports of Alicante, Cartagena and Cadiz-Seville. The volume of such ready-made Chinese silk was higher than local Marseille stockings made of thread, which shows «import-substitutions» in European local centres of production had failed, and original Chinese silk was still in high demand.

MAP 1 THE ROUX-FRÈRES COMPANY TRADE HOUSES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN FOR THE INTRODUCTION OF ASIAN GOODS DURING THE 18TH CENTURY.

FIGURE 1 STOCKINGS MADE OF CHINESE SILK RE-EXPORTED FROM MARSEILLE TO SOUTH SPAIN, 1730-1780. Units in pounds.

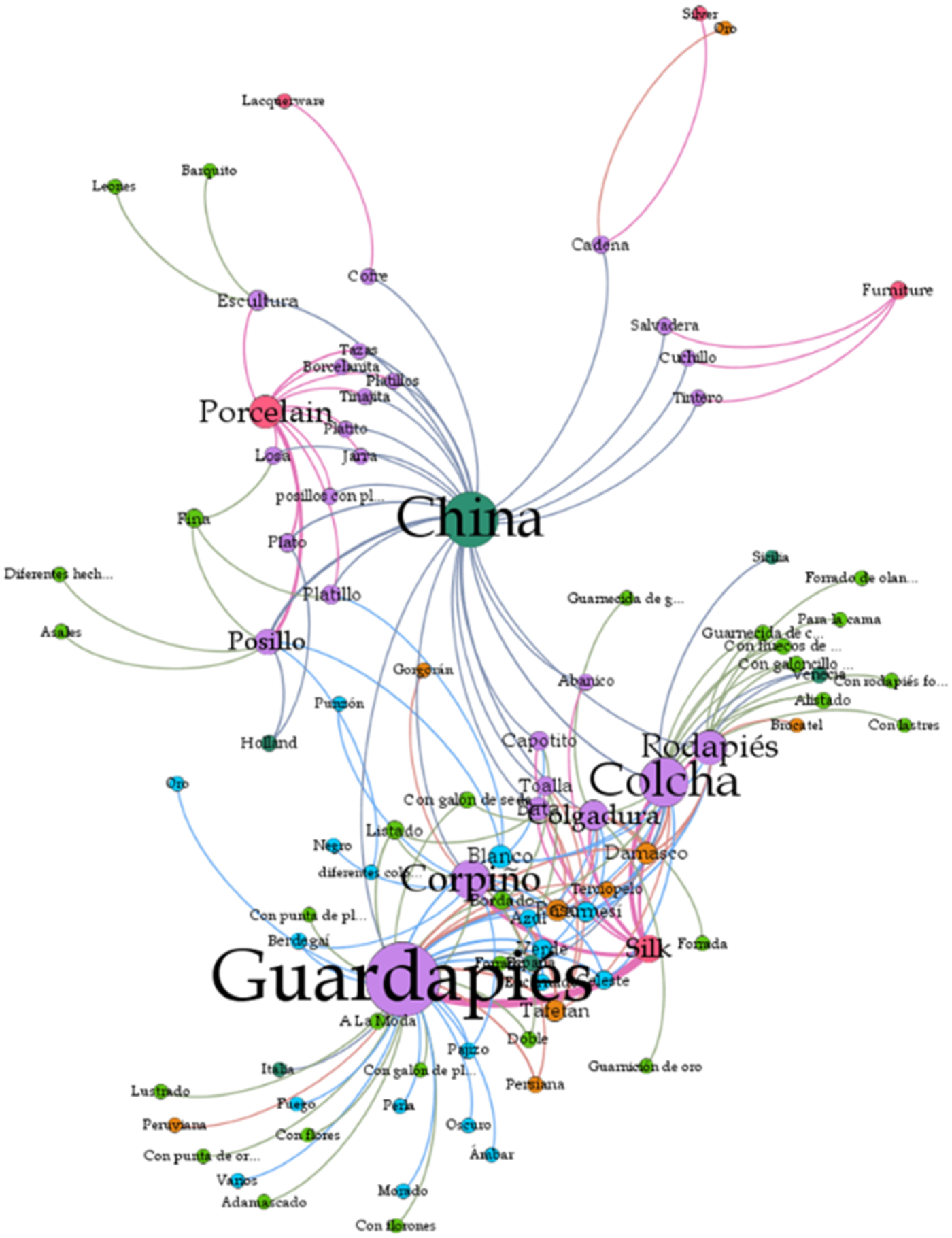

The trade networks, intermediation and coalitions between the local Chinese traders of Macao and Canton and the transnational communities that had settled in Macao (i.e. the Portuguese, the Grill and Roux Companies, French, Spanish, Sephardi, Armenians, Jesuits, among others) made the introduction of goods from European markets (in this case the example is of French, Portuguese and Spanish wines and liquors) possible and increased the demand for these goods in local communities of South China. The consequence of the local distribution and acquisition of such products was a progressive transformation of tastes, fashions and cultural identities in social groups, mainly local elites. Figure 2 shows the network of consumers of Chinese ready-made silks in which a wide array of garments (cloaks, jackets, casaca-coat, basquiña-overskirt, corpiño-bodice, pañuelo-handkerchief, etc.) and household items (guardapies, colcha-bedspread, rodapies, colgadura-hangings, etc.) were introduced to the main parishes of the city of Seville (Saint Isidro, Saint Salvador, Saint Maria Magdalena, Saint Ana de Triana, Saint Bernardo, Saint Maria la Blanca, among others). The consumers of such goods in the city of Seville were artisans, master artisans and merchants (wholesalers, retailers and peddlers)Footnote 4.

FIGURE 2 DISTRIBUTION OF CHINESE GOODS (SILK AND PORCELAIN) AMONG URBAN CONSUMERS OF SEVILLE, 1700-1780.

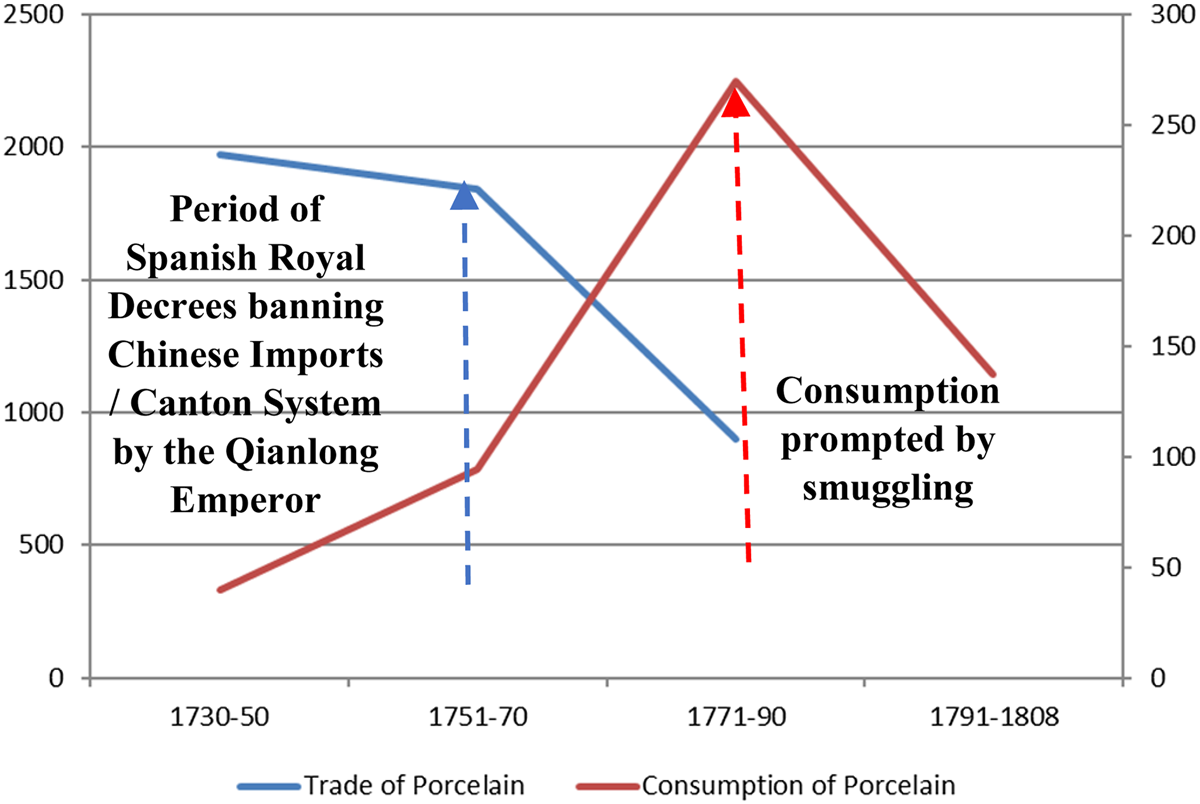

Figure 3 shows that during the period of restrictions on foreign trade in both Spain and China, when the Bourbon dynasty came to the Spanish throne and the Canton System yīkǒu tōngshāng一口通商 was established by the Qianlong Emperor in 1757, smuggling, illegal or «unofficial» trade was rife. The decline of entries of Chinese porcelains in Western Mediterranean markets (via Marseille) is evident. However, we can also see a rise in the consumption of such goods, which demonstrates that the «unofficial» channels of trade to introduce Chinese porcelains to European markets were very active. Autarky policies in both China and Europe (for the case of Spain) proved to be entirely unsuccessful.

FIGURE 3 ANNUAL TRADE AND CONSUMPTION OF CHINESE PORCELAIN IN MEDITERRANEAN SPAIN, 1730-1808.

Trade groups featuring such «unofficial» trade played an essential role as mediators, not only as suppliers by creating networks of distribution, but also by changing tastes, fashions and increasing choices for consumption. The business community in Seville-Marseille and Macao-Canton can be defined as «vicarious consumers» (Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia2013, Reference Perez-Garcia2019) as they were characterised by their role in creating and stimulating new habits of consumption through the goods they sold, but also through the goods they were consuming which had a symbolic cultural power for the transmission and emulation of new patterns of consumption.

The French traders, such as the Roux-Frères Company that introduced silks, porcelains and tea from South China into Western Mediterranean Europe via Marseille, and the Swedish Grill Company that was based in Macao-Canton and had business partnerships in the market nodes of Manila-Acapulco-Lima and Cadiz-Seville-Marseille, brought a high volume of European liquors and wines to South China. The introduction of these goods into the local markets of Mediterranean Europe and South China changed habits and fashions, increasing the demand for such commodities. Regarding Chinese goods such as silks, porcelains and tea, these items had a special connotation, reflecting the new uses in the domestic space (jars, teapots, chocolate pots, tablecloths, napkins, towels, etc.) and also in the transformation of clothing (Gerritsen and McDowall Reference Gerritsen and Mcdowall2012; Hamashita Reference Hamashita2015). Chinese goods, either for decorating the household or dressing the body, played an important role in early modern European societies. The acquisition of objects created new tastes orientated towards personal care, individual appearance and the private environment around the household. Consequently, new lifestyles and a modern consumer society were emerging.

3. MARKET INTEGRATION, CIRCULATION OF GLOBAL GOODS AND SILVER ACCUMULATION IN CHINA AND THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN: THE ROUX AND GRILL COMPANIES—BROKERAGE IN MACAO AND MARSEILLE

As previously argued, market integration, globalisation and the development of global trade should not only be analysed via economic approaches such as O'Rourke and Williamson's price convergence of the 1820s (O'Rourke and Williamson Reference O'Rourke and Williamson2004, p. 109) by which global trade is portrayed as a progression from autarky to free trade. The thesis presented by Flynn and Giráldez to understand the process of market integration and global trade seems more relevant as they identify a wide range of plausible factors behind such complex processes, moving beyond statistical analysis.

Flynn and Giráldez state that «globalization began when all heavily populated land masses initiated sustained interaction… Statistical evidence alone is insufficient to establish the beginning of globalization, a broad and profound phenomenon with multifarious linkages around the globe.» (Flynn and Giráldez Reference Flynn and Giraldez2008, p. 360). Using the concept of being «born again» these authors argue that «humans had already migrated to all of today's populated land masses prior to the end of the last ice age» (Flynn and Giráldez Reference Flynn and Giraldez2008, p. 360). Therefore, the circulation of goods, people and technology has taken place since the early days of humankind, and limiting the explanation of market integration to a concrete space (mainly the British world at the dawn of industrialisation) and chronology, the 1820s, when prices converged (O'Rourke and Williamson Reference O'Rourke and Williamson2004, p. 109) seems to be an approach that underestimates other factors such as changes in consumption, cultural changes, environmental, demographic and political transformations which were crucial factors that shaped global trade. A pertinent approach would be to investigate the linkages and connections between distant territories that allowed a global circulation of goods and commodities. The market nodes of the Pacific area, connecting South China with the Americas, and ultimately with Western Mediterranean Europe, seem to be relevant to analyse such economic phenomenon from a polycentric perspective (Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia2019), in which the historian should avoid searching for core economic areas, and rather seek multiple connections at a regional level.

When Qianlong established the Canton System yīkǒu tōngshāng一口通商 in 1757, when Canton was the only port in China authorised to trade with foreign powers, the Macao-Canton market networks fostered a dynamic exchange of goods in South China. This commercial system, which used official and «non-official» institutions fostering «non-regulated» trade and smuggling activities, operated very actively establishing a new order in Sino-foreign economic and international relations during the second half of the 18th and the early 19th century. This new socio-economic and political landscape created the grounds of the conflicts and trade relations between China and Western powers that culminated with the Opium Wars. The structural factors related to the economic divergence between China and the main European economies might be better grasped by moving beyond the rigid analysis of GDP per capita and commodity price convergence. It is necessary to understand that market integration and connectivity with far-away lands was mainly due to the circulation of goods and long-distance business partnerships beyond the realm of official institutions. The paradigm of such an informal, «unofficial» trade system is evident by looking at the Sino-foreign economic exchanges in the city ports of Macao and Canton. Changes in consumer behaviour fostered through the introduction of European goods such as wines and liquors in South China, the high credit and loan interest rate to secure trade ventures in Macao and Canton, and the Confucian modus operandi of Chinese traders and the «foreign» (not Han) Manchu dynasty are all crucial factors for understanding the economic drivers and the process of policy-making in 18th and 19th-century China. Market integration between Western and Eastern markets might be better understood considering these socio-economic, cultural and political conditions.

Through a profound analysis of the new international scenario created by the Qing rulers, mainly the Qianlong emperor and his Canton System, some fundamental issues regarding local trade, the introduction of Western goods, trade alliances and the credit market may be better understood. This includes: (1) the way economic competition among the European powers was used to control Chinese markets; (2) the operation of the Chinese market, as well as the role of tariff barriers and smuggling activities which fostered market integration; (3) the increasing demand for Western goods by local Chinese traders in Canton and Macao. These characteristics basically articulate the socio-economic and political relations between China and Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The economic competition between European powers during the 18th century, especially between England and European trading companies such as the French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch or Swedish companies, was all about gaining control of China's markets. Control over the tea market was a crucial aspect of this competition. The British monopoly of the tea trade often hindered the commercial operations of their European rivals. This caused diplomatic disputes as there was no regulation of that trade. The strategy of French, Spanish and Swedish trade companies was, therefore, to engage in alliances to introduce other goods (i.e. French and Spanish liquors and wines) to South China, creating a new market and demand. The British East India Company (E.I.C.) strengthened its monopoly of the tea trade in China. At the end of the 18th century the British established a permanent embassy in Beijing with the aim of consolidating their monopoly and sought new markets in the Chinese provinces to sell English wool, raw Indian cotton and opium.

However, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Swedish companies bypassed this British economic hegemony in China's markets, by establishing alliances and partnerships between themselves and with the Hong merchants of Canton. They created a new market in South China to introduce European wines and liquors. Analysing the functioning of local Chinese markets, as well as tariff barriers and smuggling activities, from a comparative perspective seems to be crucial for shedding light on the local and foreign trade in China. It may also help to explain why such trade dynamism, or the so-called «sprouts of capitalism» (Li Reference Li1998) in China, did not translate into higher levels of economic development—as occurred in North-western Europe. The special features of local Chinese markets should be further researched by historians as they may offer a deeper insight into the process of market integration in China, Southeast Asia and Europe, and show to what extent trade partnerships favouring the exchanges of goods were a determining factor in such market integration. The role played by international trade networks was crucial, as was their ability to convey information on customs duties and to bypass the high tariff barriers through smuggling activities. Fiscal evasion and payment of the so-called almojarifazgos (royal tariffs levied in the ports of the Spanish empire) (Schurz Reference Schurz1939; Chaunu Reference Chaunu1960, pp. 148-160; Atwell Reference Atwell1982, pp. 68-90; de Souza Reference De Souza1986, pp. 67-84) by the Chinese junks trading in Manila became a common practice by which international trade in Southeast Asia and South China via Macao-Canton operated through the exchange of American silver for Chinese goods (Flynn and Giraldez Reference Flynn and Giraldez1996, pp. 52-68).

The brokerage system was institutionalised by the Qing government through licences which were granted to brokers who were in charge of supervising commercial transactions. It was illegal to carry out transactions without a government licence and so unlicensed brokers proliferated and thus weakened the system, in turn stimulating smuggling activities. These unofficial practices in China were promoted by merchant guilds, huìguǎn 会馆, and self-governing organisations (Quan Reference Quan1933; Chen Reference Chen2001, p. 163; Shiu and Keller Reference Shiu and Keller2007, p. 1,193). Therefore, the following question should be addressed: were smuggling activities a major channel of the Qing government's trade revenue as interregional commercial networks were managed by the Qing officials and gentry that controlled the huìguǎn?

Seasonality and unregulated trade on the South China seas were common features during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The overseas trade regulations of Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong, the three emperors of the so-called «High Qing» period, an era historiographically acknowledged as particularly prosperous, varied according to their policies as Kangxi opened customs offices, then Qianlong closed them and only kept the Canton Yuè/Canton Customs 粤海关 yuè hǎiguān.

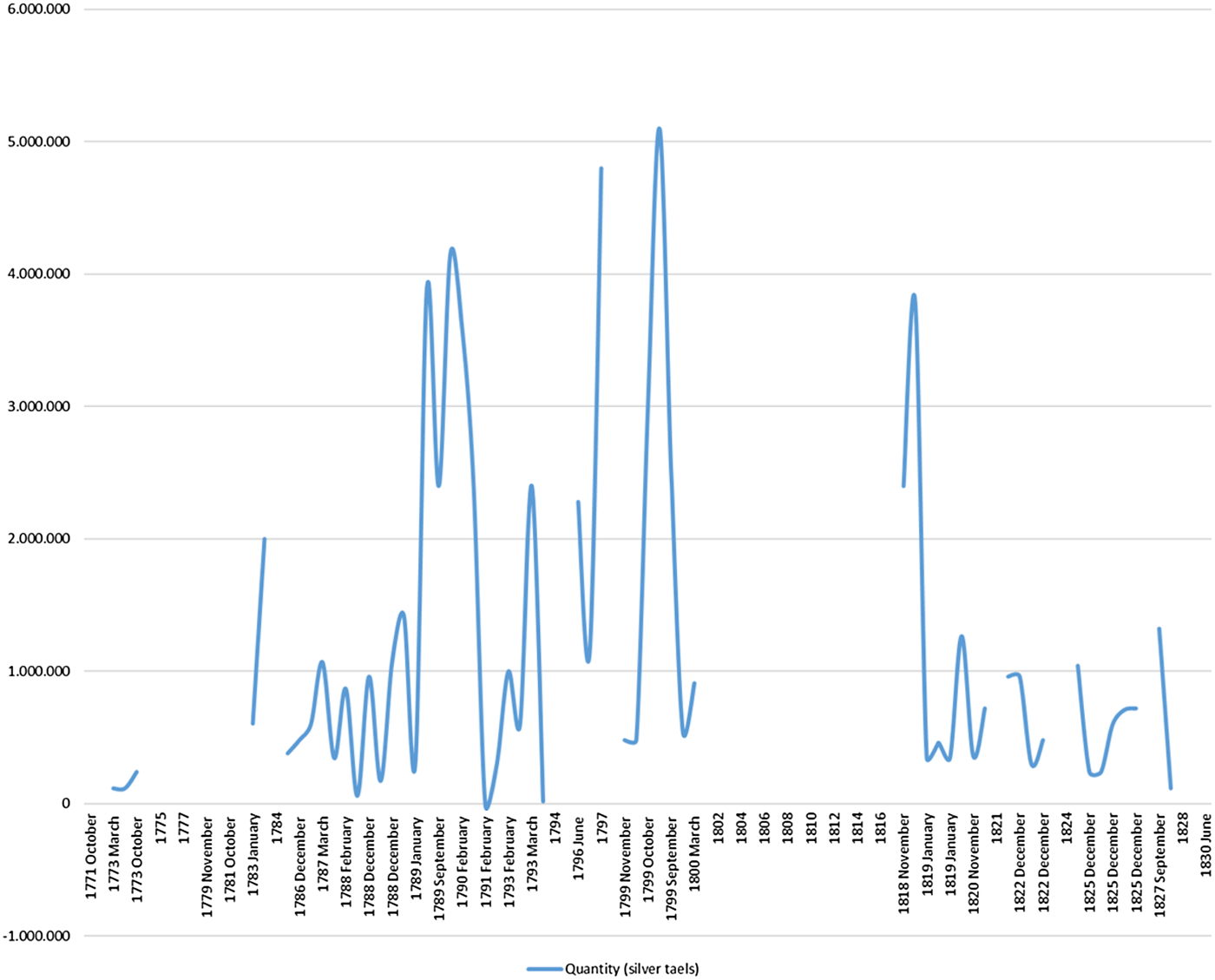

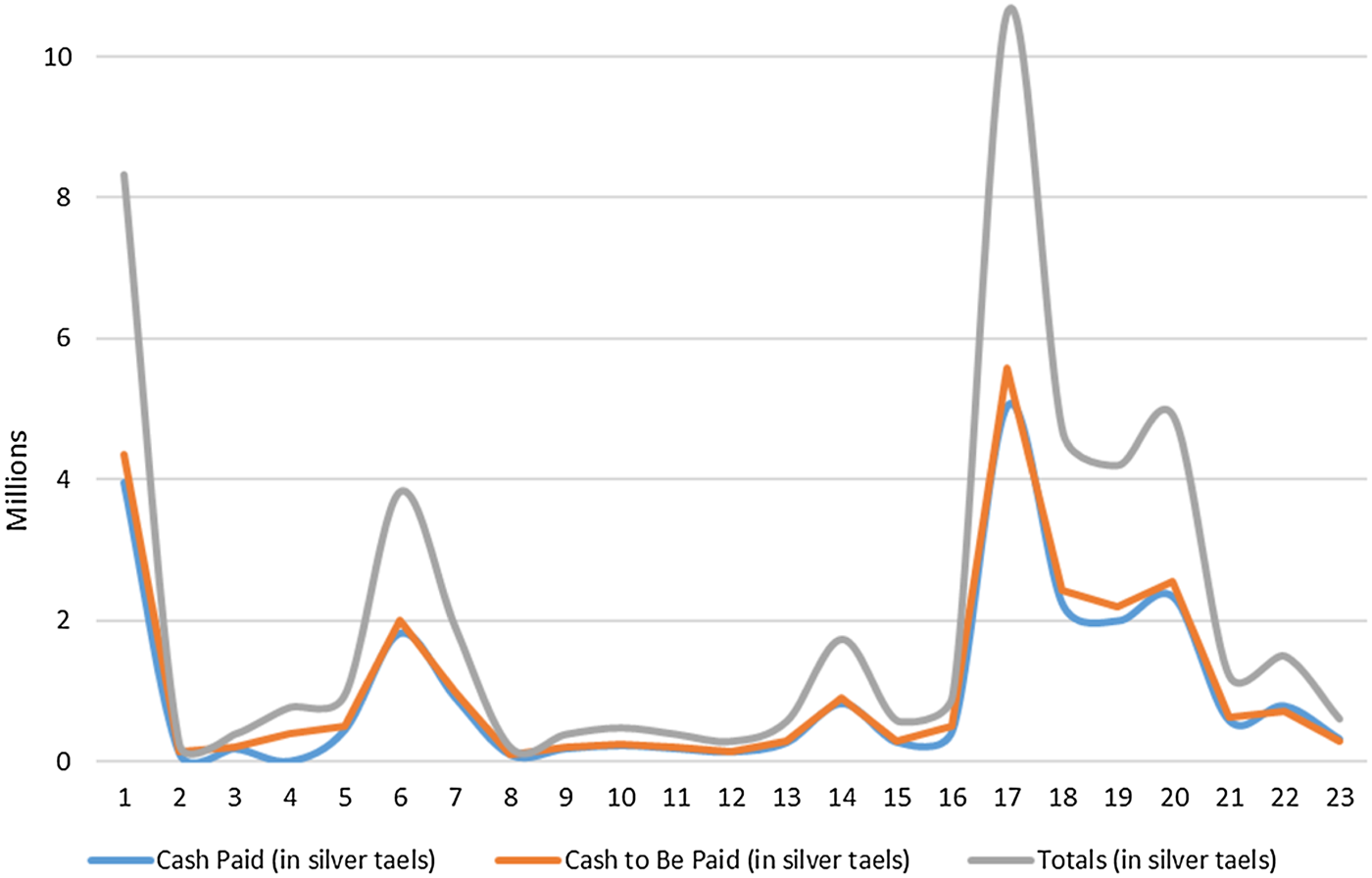

The climate of internal instability provoked by the economy and trade policies of the Manchu emperors exposed the inability of the state to control trade and manage revenues of the flows of exports and imports in South China, mainly in Canton. The activities of Macanese traders were thriving and due to the risk inherent to maritime ventures they were specialised in credit systems as «they loaned silver with an interest of 35%» (Ng Chin-Keong Reference NG1983; Von Glahn Reference Von Glahn1996). As can be seen in Figures 4 and 5, the Santa Casa de Misericordia de Macao (the Holy House of Mercy of Macao) and the group of Portuguese merchants that controlled this institution would grant maritime trade insurances and loans due to the seasonality of Chinese maritime trade, the unregulated market, perilous weather conditions and general risks of sea-faring activities and piracy. Given the very unstable conditions for trade in the South China seas, the Holy House of Mercy of Macao (Diaz de Seabra Reference Diaz De Seabra2011; de Sousa Reference Perez-Garcia2019) was in serious debt by the end of the 18th century and especially during the years when the Canton System was imposed by the Qianlong emperor.

FIGURE 4 MARITIME TRADE DEBTS OF THE HOLY HOUSE OF MERCY OF MACAO (1771-1830). Units in silver taels.

FIGURE 5 VALUE OF MARITIME INSURANCES IN MACAO, 1796. Unit in silver taels.

The credit and loan system of the Holy House of Mercy of Macao was one of the main channels for the introduction of American silver as a global currency in the South China market circuits. These silver coins were in great demand among private Chinese merchants. The trans-Pacific routes directly linked Spanish American silver production areas in Bolivia, Peru and Mexico to Manila in the Philippines through the Manila galleons, which regularly sailed westward from Acapulco to Asia. After 1640 the bulk of silver imported into China was of American origin. Macao received enormous amounts of silver and goods from Europe. In order to prevent the continued flow of silver from America to China, the Spanish monarchs established the above-mentioned tariff decrees, as well as restrictions to trade with China, however, they failed in this endeavour.

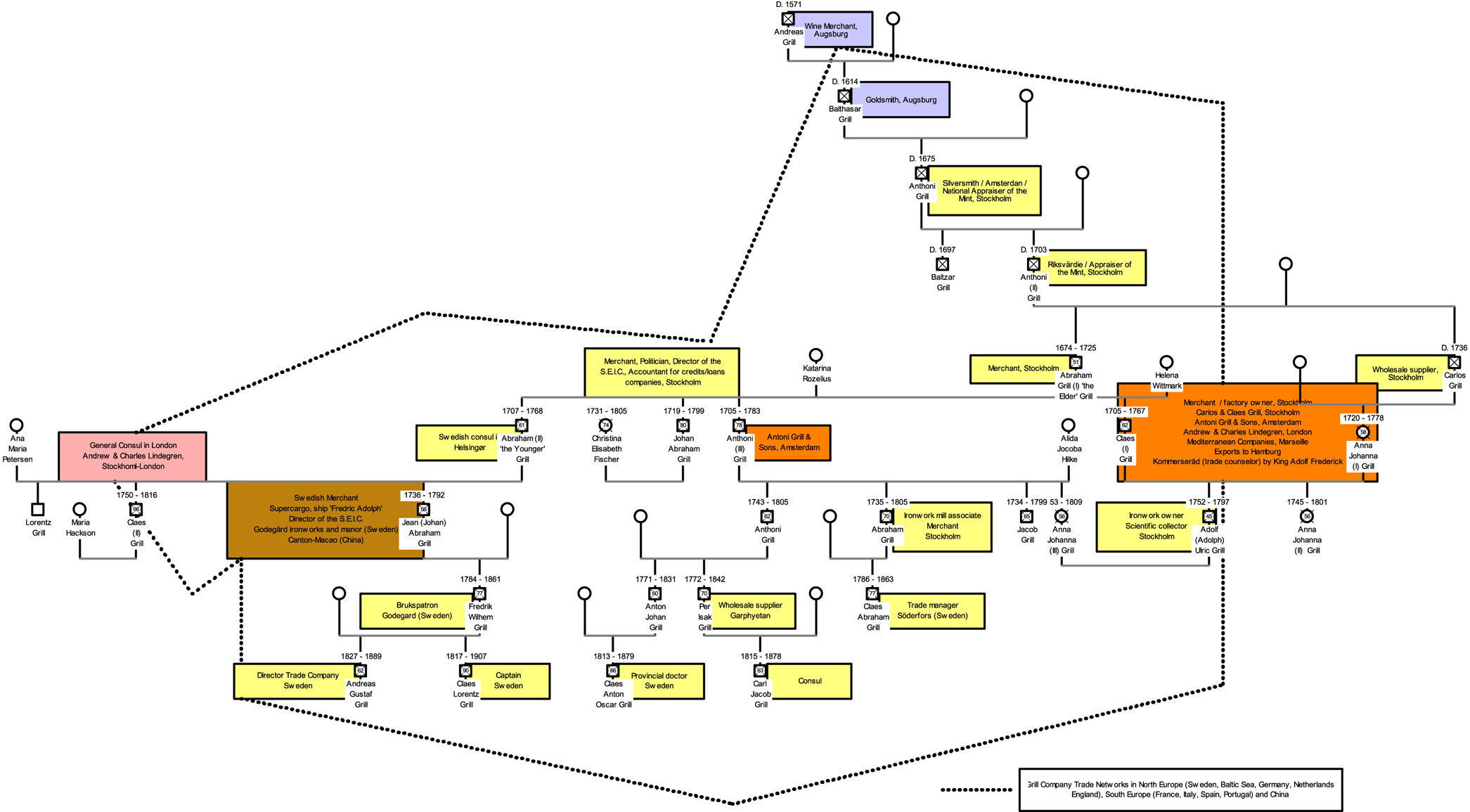

Analysing the letters of credit, and contracts for silver and goods enables one of the most challenging parts of this research to be undertaken: to trace the trade networks that European merchants established in the South China Sea through Macao (see in Figure 6 the Grill genealogy and the brokerage system that the Grill family created in Asia, Europe and the Americas, Figure 7). They created a global network that connected the West with inner China (Ng Chin-Keong Reference NG1983) through the main port cities of Canton, Xiamen or the old Amoy, Ningbo and Shanghai. Canton was one of the main sites for the introduction and distribution of foreign goods. Among the most relevant Chinese family merchants who operated in Macao are the Ch'en Shun-hsing, Ts' ai Hsing-li, Lin Yüan-hsing, Ch'iu Ho-hsing, Li Yüan-mei, K'e Ying-hsing, K'e Jung-sheng families (Ng Chin-Keong Reference NG1983).

FIGURE 6 GENEALOGY OF THE GRILL FAMILY, GARPHYTTAN AND GODEGARD HOUSE OF SWEDEN (1638-1907).

FIGURE 7 THE GRILL COMPANY AND THE BROKERAGE SYSTEM BETWEEN MACAO-CANTON AND MARSEILLE-SEVILLE, 18TH century

During the 18th century the Swedish Grill family, headed by Jean Abraham Grill (1736-792), also known as Johan Abraham Grill, became one of the most successful business families in Macao and Canton establishing contacts with local Cantonese and Hong merchants. Jean Abraham Grill followed in the footsteps of his father, Abraham Grill «the younger» (1707-1768), to become the director of the Swedish E.I.C. (S.E.I.C.) and was also a supercargo and merchant in Canton and Macao where the firm moved its business during the second half of the 18th centuryFootnote 5.

The socio-professional category of this group in Sweden during the early modern period (the 17th and early 18th centuries) was largely related to the artisan and business sector as they were specialised in iron production, as well as mill manufacturing. In addition, the family had a strong trade orientation importing and exporting goods such as Chinese porcelains (Van Gent Reference Van Gent2016, pp. 388-409), silks and tea to and from the Far East, as well as owning ironworks and mills manufacturing goods for export while operating leading trading houses and working in wharfs, textile companies, mills and other factories related to shipbuildingFootnote 6. The family, whose origins were in Genoa, Italy, had migrated at the end of the 16th century to Augsburg, where they received the coat of arms and were part of the complex network of financers of the Habsburgs (Garcia-Monton Reference Garcia-Monton, Muto and Terrasa Lozano2015, pp. 73-93). The family represents an outstanding case of social mobility as they became a noble family in Swedish, Italian and Castilian territories. The silversmith Anthoni Grill (I), grandson of Andreas Grill, was born in 1638 and was a burgess in Amsterdam, moving to Stockholm, Sweden, in the second half of the 17th century. The family was shaped by two main branches, the Garphyttan and the Godegård branch (Müller Reference Müller1998, Reference Müller2004)Footnote 7.

Jean Abraham Grill, who was the main head of the Grill Company (see the Grill genealogy in Figure 6) and became the director of the S.E.I.C. in 1778, was a trainee merchant in Montpellier and Marseille, where he had worked for the firm Mallet & Blancherey. In 1761 he became the fourth supercargo of the Frederic Adolph sailing to South China, to Macao and Canton, with a valuable cargo of silver. He stayed in Macao and Canton from 1761 until 1769. Jean Abraham Grill and his company traded between Canton, Macao and Manila, and Acapulco, Lima connecting the Pacific, Atlantic and Mediterranean routes through the economic axis of Cadiz-Seville-Cartagena and Marseille. From Marseille, where the company had its main partnership with the Mallet & Blancherey firm and the Roux Company, the Mediterranean and North European markets were integrated, creating a monopoly for the circulation and introduction of Asian goods in European markets, as well as strategic partnerships in the Pacific market to introduce European goods into South China via Manila-Macao-CantonFootnote 8.

Transactions and trade exchanges were mainly undertaken through letters of credit and silver to import Chinese goods (silk, tea and porcelain) to American and European markets and to introduce to South China (via Macao and Canton) European goods such as pocket watches, Mediterranean coral and European liquors and wines from France, Portugal and Spain. This transformed the consumer behaviour of the South China local elites and gentry. This complex credit-mercantile system was similar to the silk and cochineal trade of Mexico, as well as Atlantic and Pacific markets, during the 17th and 18th century (Ibarra and del Valle Pavon Reference Ibarra and Del Valle Pavon2017; Marichal Reference Marichal, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018; Suarez Reference Suarez and Martinez Ruiz2018). Marseille functioned as the main entrepôt during the 18th century due to the context of political stability after the end of the Spanish Succession War, the cordial relations with the Ottoman Empire and the geostrategic location connecting the Western Mediterranean with the Levant for the entry of Asian goods. The main partner of the Grill and Roux family in Marseille was the Sollicoffre family (Solicofre in the Spanish sources), a renowned Marseille family that established trade houses in the port of Cartagena, introducing silk from China through their alliances with the local trade families of Cartagena and Marseille, such as the Brunet familyFootnote 9. Nicolas de Sollicoffre (a French citizen) was appointed as the first consul of Sweden in Marseille in 1731 (Carrière Reference Carrière1973; Müller Reference Müller2004, p. 116).

The Sollicoffre, Grill and Roux families were the main families to have trade networks connected with retailers and small trade family groups in the Western Mediterranean (Marseille-Cartagena-Cadiz-Seville) and in the South China Sea (Manila-Macao-Canton). Grill, Roux and Sollicoffre connected East Asian and Western Mediterranean markets through a brokerage system of letters of credit, purchase of goods and silver circulation (see Figure 7). In Macao-Canton via Manila the alliances with the governor and captain general of the Philippines, don Simon de Anda y Salazar, the elites of the islands (merchants and alcaldes) and the sangleyes Footnote 10 allowed the Grill, Roux and Sollicoffre families to establish a profitable trade of Chinese silk; they bought cheap silk, which was produced in Suzhou, Hangzhou and Nanjing, from the Canton market and sold it to their European partners, thus raising the demand for such goodsFootnote 11. Their main partners in Canton-Macao were the Hong merchants. The brokers bought cheap Chinese silk with credit lent with very high interest rates creating an extremely profitable business. Financers (from Canton, Macao and Europe) were thus funding the purchase of cheap silk in China that was to be distributed in Europe at low prices. This collapsed the local silk market and production in Europe, which could not compete with the high quality and low prices of Chinese silk. The Grill letters are an exceptional new historical source that demonstrates how local elites in Europe, Manila and South China managed to bypass the official channels and institutions that had been created during the 18th century by the Spanish and Chinese empires to regulate long-distance trade. On the contrary, this long-distance trade and partnership worked through trust and intermediation by issuing credits, bills and promissory notes.

«…una carta de que he recibido de Mons. Obry y en ella una Oblign. y una certificac. que V.M. le dio de come M. Bene y le avia entregado al Sangley al fiar de algunos efectos para mi: me causaba admiración y por cierto por averme luego acordado que cuando yo le escribi a V.M. a Mansinloc me respondio que el Sangley dezia que no traya nada para mi y aora veo que V.M. da una certificación de como lo traya. Si no lo viera y no lo hubiera visto de bajo de su firma no lo creiera: pero me veo obligado a creerlo o rebentar; doy las gracias de sus favores y solo digo que se acuerde V.M. de q. los Montes no se encuentran pero los hombres si…»Footnote 12

This letter written by the governor of the Philippines, don Simon de Anda y Salazar (a partner of Johan Abraham Grill in Manila), was addressed to don Juan Solano and don Jorge de Sanclemente who resided in Mansinloc (a province of Zambales in the Philippines) demanding the payment of a silk cargo sold «al fiar» (on credit) and brought from Canton by a sangley who acted in Macao and Canton in partnership with the French merchants monsieur Bene and monsieur Martin in January 1762Footnote 13. The city of Mansinloc occupied a geostrategic location for trade connecting the Philippines with South China, mainly Macao and Canton. In a subsequent letter don Simon de Anda y Salazar gave further details about the delayed payment due to the trade blockade in the Philippines by the British, who had not noticed or more likely were not willing to stop the conflict with Spain and France when the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years' War in 1763. Don Simon de Anda y Salazar was desperate as he forwarded the letters to the court in Madrid and to the king himself asking for assistance against the British. The king, of course, sent no fleet and the Spanish colonies in the Pacific, just like those in the Americas, were left to be managed by local elites.

The debt claimed by don Juan Francisco Solano and don Jorge de Sanclemente, acting as mediators/agents, was the remaining payment, either in goods or cash, of the silk manufactures (capotillos de seda pintados) sold «al fiar» in Canton in January 1762 to the sangley for the value of 91.4 pesosFootnote 14. Don Juan Francisco Solano and don Jorge de Sanclemente received 500 silver pesos from the company, which bought a ship to bring from Canton the following items:

• 8 «capotillos de seda pintados bordados de oro y plata» (painted silk cloaks with gold and silver embroidery) to the value of 336 silver pesos

• 2 «sayas de seda de mujer» (silk skirts for women) to the value of 61 silver pesos

• Plus a commission of 2.5% out of 500 silver pesos = 12.4 silver pesos

The letter written in Spanish included a French translation for the French partner in Canton, monsieur Martin.

On 7 April 1764, another letter from Macao written by don Juan Francisco Solano, in Portuguese, was addressed to don Gregorio San Clemente wishing him a good trip to Macao, as Sr. Grubb (Mr. Grill = John Abraham Grill) had left Manila for Macao in January 1764, asking for news about the «Sr. Pankequa sempre sem fiso mucho servizio». «Pankequa», as it appears in Portuguese was the president of the Cohong (gonghang 公行) jointly with his brother. In other sources his name appears as Poankeequa (Pan Zhencheng 潘振承) and brother Sequa (Pan Seguan 潘瑟官) who were the presidents of the Cohong, the firm was called Tongwen Hang 同文行 (Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2017, p. 6).

Don Juan Francisco Solano asked his partner don Gregorio San Clemente if he had bought «grana» cochineal at the expense of the firm/company as recently a British ship had arrived in Manila selling around 10 or 12 «picos» of «grana» cochineal for 4 silver taels/catty. Many more cargoes were expected that year as more ships from Europe, Goa and the coast of Batavia were to arrive. From the English ship don Juan Francisco Solano and John Abraham Grill received letters asking for more cargoes of «grana» and other goods from Europe. Don Juan Francisco Solano had sent letters to his partner Gregorio Chang (a sangley in Manila) and such letters might have «causas contrarias a nosso interese, por la carga, y principalmente aquellas a los armenios; que V.M. pudiera ver a tras de cada carta; deixo a la prudenzia de remitirlas apresto a la chegada del Champan…»Footnote 15

A Champan 三 板 (sam pan) was a type of Chinese and Japanese fishing vessel that is frequently mentioned in the Spanish 17th and 18th-century historical sources referring to the trade in the South China Sea, mainly connecting the city ports of Nagasaki, Canton, Macao and ManilaFootnote 16. Don Juan Francisco Solano reported details of other European goods that were highly demanded in Macao and Canton, such as European wines and liquors:

«…tengo un poco miedo que hemos cargado mucho aguardiente mas nao se podia remedir ahora y perque ainda y por la ajuda del Sr. Pankequa, el Conhang tem guardado 10 ou 15 Letras e se le pudiera facilmente enviar ainda 50 outras, mas y por vino Jerez…Espero y mim fio a V.M. por la buena venta de aquellas mercancías, y perque certamente sim seu conselho, nos cunca tendraimos comprado tanto…Debe agora V.M. al Senhor Grubb y mim por este cargo de los Mexicanos 6,342.240 pesos de plata que es la tercera parte de la compra do cargo y gastos, y con 30 por cento quando sera llegado y torna aqui, que sera por todo 8,246.240 pesos de plata, y no caso que V.M. pudiese suponer que la carga de su retorno nao havia de tender tiempo que este caudal y 1500 o 2000 pesos mas, y por mas gastos aquí; y sepa V.M. de manda ainda algum caudal mas por su cuenta, y para pagar a nos…»Footnote 17

Another letter sent to Pankequa and Johan Abraham Grill by the king of Spain and the captain and governor of the Philippines, which was forwarded to Gregorio Chang, the sangley in Manila, discusses a cargo of silk linen brought by the French merchant DumondFootnote 18. The Spanish government was concerned that Chinese silk entering Spain would affect local production in Spanish silk workshops, as well as the constant arrival of English ships to Manila. Pankequa and Grill sent samples of various goods to show their quality and form: «…de las cualidades de cargas que sirven por los indios y otras mercancias de aquí, buenas por las Islas Philipinas y por Acapulco y también de Europa.»Footnote 19 They also emphasised the amount of American silver pesos needed to buy Chinese goods (mainly silks) for such low prices that were introduced in Acapulco via Manila. A list of goods, prices and expenses is attached to the letter:

«…mercancias embiadas por las Yslas Philipinas con el Champan Quin Consay, Capitan San Matay, y por cuenta tercera entre los Senhores D. Jorge Sanclemente, Pankequa y Grubb o Grill, dirigidos por la venta ao dicho Sr. San Clemente o por su falta a D. Galban oidor en las dichas Yslas…»Footnote 20

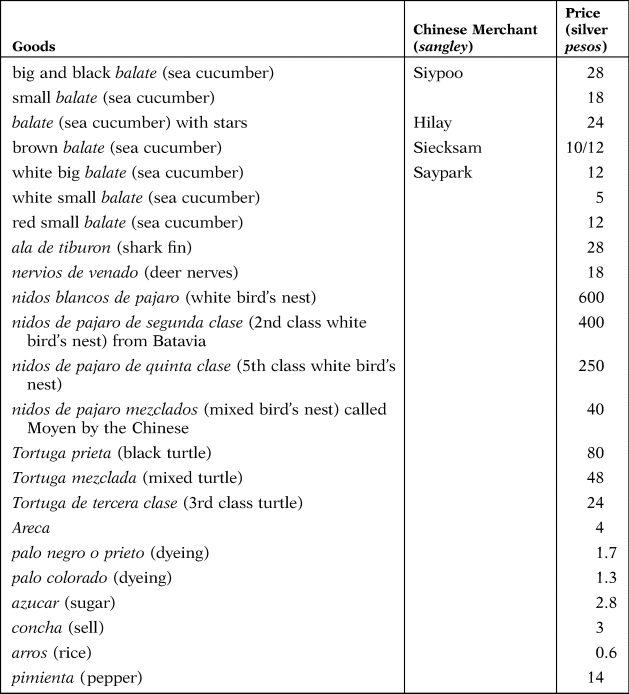

Other goods shipped from Manila to Canton in the cargo of the champan Quin Consay, captain San Matay, were foodstuffs such as: balate (a variety of sea cucumber that was very popular in China and which was imported to Europe from China)Footnote 21, nervios de venado (deer nerves), nidos de pajaro (birds' nests), alas de tiburon (shark fin), tortuga (turtle), areca (a fruit used as a textile dye as well as being used in the Philippines to make buyo—in the French Grill letters it appears as bois bouge—which is chewed in East Asian countries)Footnote 22; palo negro o prieto (black dye), clavo (clove), nuez moscada (nutmeg), palo colorado (red dyeing), azucar (sugar), concha (shell). In a letter signed by Pankequa and Grill (partners in Macao-Canton)Footnote 23 they appeal to the goodwill of their partners in Manila to protect the investment and cargoes of goods «por o que demas pedimos a V.M. de hazer por el mas buen de fe y de noso intereses pedimos a Dn. Gregorio Chang…», the sangley in Manila in charge of shipping the goods from Manila to Macao-Canton and Canton-Macao to ManilaFootnote 24.

The foodstuffs from the Philippines and dyes from New Spain were highly demanded by the Macanese and Cantonese communities due to the trans-cultural dimension of such social groups of South China, which can be observed in the variety of culinary tastes and consumer choices of such cosmopolitan societies (Perez-Garcia Reference Perez-Garcia2013, Reference Perez-Garcia, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018a, Reference Perez-Garcia, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018b, Reference Perez-Garcia2019; Marichal Reference Marichal, Perez-Garcia and de Sousa2018).

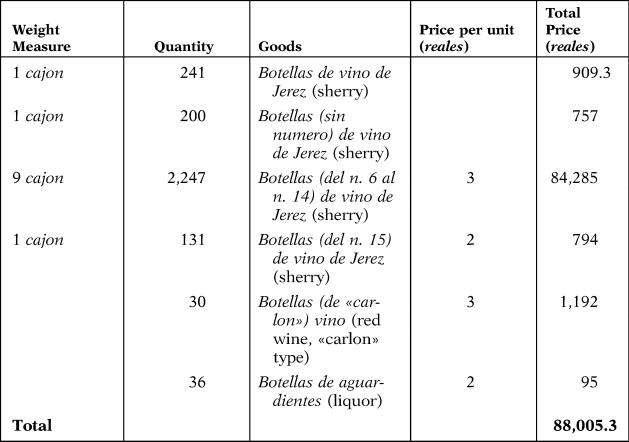

The main revenue behind this brokerage system and business partnership for the exchange of goods in Macao-Canton (see Map 2) and the introduction of American silver, via Manila, was the speculation of prices as seen in Tables 1 and 2. Table 2 shows the price of vino de Jerez (sherry) shipped from Seville-Cadiz to Manila at a rate of 2/3 reales per bottle, but when selling the same product at the bazaars of Macao-Canton, the Grill Company and its partners in Manila and Macao-Canton raised the price per bottle to 22 silver pesos.

MAP 2 SINO-WESTERN MARKET INTEGRATION VIA MACAO-CANTON: AMERICAN SILVER FOR CHINESE SILK AND PORCELAIN, 17th AND 18th CENTURIES.

TABLE 1 LIST OF SPANISH WINES AND LIQUORS (AGUARDIENTE) SOLD IN MACAO-CANTON VIA MANILA BY THE GRILL COMPANY, 1764

Source: A.H.M., S.E.I.C. Series: F17, vol. 1A, vol. ID: 17:1A and vol. 1 B, vol. ID: F17:1B, Grill Letters, ref. T1_00733.

TABLE 2 CARGO OF SPANISH WINES AND LIQUORS (AGUARDIENTE) IN THE SPANISH SHIP NUESTRA SEÑORA DEL ROSARIO ARRIVED IN MANILA, 1769

Source: Archivo General de Indias (A.G.I.), Sevilla, FILIPINAS, 942, N.2. See also Sanchez de Mora (Reference Sanchez De Mora and Sanchez de Mora2017, p. 156).

Speculation, but also the opium trade and smuggling activities created the main profits of the partnership established by the Cohong Pankenqua and Johan Abraham Grill. Indeed, the Cohong and Grill's fortunes were based on these risky activities. The precarious nature of this illegal trade is evident from a letter sent by signore Sigismundo di San Nicolas (letter sent from Beijing in January 1764) to the British merchant Robert Jackson, who had settled in Canton-Macao and was a broker and partner of Johan Abraham Grill:

«…I was very sorry to see by the content of your letter that you could not yet sell your Ophium [sic], and that consequently there is very little hope that you can pay me the balance of our account in time for the contract; you might be entirely assured of my friend, that I would not by any means engage you to sell your Ophium [sic] to a low price for this purpose thought it is certain that the money would give me profit, but it does not signify, being for to serve a friend; but I do not doubt that you are so reasonable at your side not to pretend that I shall lose a years of interest for it; you know very well that for to make contracts of thea [sic], I pay myself 12 and 15 percent a year and you know very well that this money remains always fruitful in my cheap bills about this time and that there is very little or no occasion for me to employ the money before 8 percent bill this time, so that not getting the money before 7 percent does me entirely years of difference; and this is the reason why Mr. Grubb (Grill) or I have not asked you about the money before; please to consider this and to resolve which you chuse [sic] the best. There are damd [sic] troubles in the Conghang and no contracts are yet made, but will be in a few days so that in case you will send the money the sooner will be the better.»Footnote 25

A copy of the letter was sent to signore Philippo Ayarg, also a partner of Sigismundo di San Nicolas, who was selling tea from Macao-Canton to Beijing. The Grill family also had an extended business network in England as one of the family members, Claes (II) Grill, was consul in London and partner of the Anglo-Swedish company Andrew & Charles Lindegren. The Grill family was also involved in smuggling activities and made a fortune in the opium trade, which they appear to have used to fund political movements against the king of Sweden (Kjellberg Reference Kjellberg1975).

4. CONCLUSIONS

By cross-referencing sources from Macao, Marseille, Seville and Sweden, this research provides new historical evidence that the first globalisation occurred earlier than 1820, contrary to what Williamson and O'Rourke argued through their hypothesis on price convergence. The credit letters and brokerage system established by the Grill and Roux activities in the South China Sea (Macao-Canton and Manila) and Western Mediterranean Europe (Marseille-Seville and Cadiz) show how East Asian and European markets were integrated through local elites and trade networks which bypassed the regulations of official institutions. The circulation of Chinese goods in Europe (silk, porcelain and tea), European goods (wines and liquors) in China, and American silver as a global currency that was highly demanded by Chinese merchants contributed to such market integration.

The main trade companies and local elites in Macao-Canton, Manila and Seville-Marseille, circumvented official institutions and mercantilist policies, which aimed to regulate trade, thus creating an «unofficial trade» system which was fostered by the main officials of both the Chinese and Spanish empires. High taxes were charged by the Cohong and Hoppos (see Tables 3–5), as well as the governor and elites in Manila organising their own trade system avoiding the decrees issued by the monarch in Madrid. Autarky in both China and Spain failed, and the smuggling trade proliferated when bans on the introduction of Chinese goods into Spain were issued, and the Canton System was established by the Qianlong emperor. European trade companies such as the Grill company, in alliance with local traders of Macao-Canton, created a new demand in South China for European goods (wines and liquors) as shown by the sources.

TABLE 3 COMMISSION, RATE (%) LEVIED BY THE HOPPOS, 1764

Source: A.H.M., S.E.I.C. Series: F17, vol. 1A, vol. ID: 17:1A and vol. 1 B, vol. ID: F17:1B, Grill Letters, ref. T1_00733.

TABLE 4 OTHER EXPENSES, 1764

Source: A.H.M., S.E.I.C. Series: F17, vol. 1A, vol. ID: 17:1A and vol. 1 B, vol. ID: F17:1B, Grill Letters, ref. T1_00733.

TABLE 5 TOTALS OF EXPENSES FOR TRANSPORT AND SHIPPING GOODS TO MACAO-CANTON, 1764

Source: A.H.M., S.E.I.C. Series: F17, vol. 1A, vol. ID: 17:1A and vol. 1 B, vol. ID: F17:1B, Grill Letters, ref. T1_00733

Traditional European historiography, mainly for Spain, has observed the demand for European goods and Southeast Asian goods, as shown in Table 6, only among the elites in Manila. The same applied to the silk market in Western Mediterranean Europe, as the Spanish historiography has overestimated local production («import-substitution»). Instead, it has been shown that Manila was the linchpin connecting the South China markets with the Americas and Europe. Cross-referencing the probate-inventories of Mediterranean Spain (Cartagena and Seville) with the trade letters of South China regarding purchases by the sangleyes, and European traders settled in Mediterranean Spain, shows that an important volume of silk products listed in Spanish probate-inventories are of Chinese origin. This demonstrates how markets were well-integrated and beyond the control and regulation of the official institutions. The «Asian-Mediterranean brokerage system» was the main instrument implemented by powerful trade families and local elites such as the Grill and Roux families, establishing a system of trade networks and long-distance alliances with other families in South China (Macao-Canton), the Philippines (Manila) and Western Mediterranean Europe (Marseille, Cartagena, Cadiz, Seville).

TABLE 6 PRICES OF THE FOODSTUFF AND DYESTUFF SHIPPED FROM MANILA AT THE BAZAAR OF CANTON, 1764

Source: A.H.M., S.E.I.C. Series: F17, vol. 1A, vol. ID: 17:1A and vol. 1 B, vol. ID: F17:1B, Grill Letters, ref. T1_00736.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been sponsored and financially supported by GECEM (Global Encounters between China and Europe: Trade Networks, Consumption and Cultural Exchanges in Macau and Marseille, 1680-1840), a project hosted by the Pablo de Olavide University (UPO) of Seville (Spain). The GECEM project is funded by the ERC (European Research Council)-Starting Grant, ref. 679371, under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, www.gecem.eu. The P.I. (Principal Investigator) is Professor Manuel Perez-Garcia (Distinguished Researcher at UPO). This work was supported by H2020 European Research Council. This research has also been part of the academic activities of the Global History Network in China (GHN) www.globalhistorynetwork.com. Manuel Perez-Garcia is the director and founder of the GHN. This research is a result of the panel «Beyond the Silk Road: The Silver Route and the Manila—Acapulco Galleons for the Global Circulation of Goods and People in China, Europe and the Americas» organised by GECEM Project at the XXXVI International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA)/Latin American Studies in a Globalized World hold in Barcelona, Spain, 23-26 May 2018. It is also a result of the panel «Social Network Analysis and Databases for New Comparative Global History Studies in China, Europe, and the Americas» organised by GECEM Project at the XVIII World Economic History Conference/Waves of Globalization held in Boston, United States, 29 July–3 August 2018. I am grateful to comments and suggestions made by professor Dennis Flynn, Patrick O'Brien, Pat Manning, Joe P. McDermott, Leonard Blusse, François Gipouloux, Debin Ma, Leonor Diaz de Seabra, Antonio Ibarra, Robert Antony, Liu Shiyong, Qiu Pengsheng, Zhang Yi, Cai Xiangyu (Ellen), Li Qingxin and Wang Zhenzhong. Special thanks to GECEM team members such as Omar Svriz, Manuel Diaz Ordoñez, Bartolome Yun-Casalilla, Marisol Vidales Bernal, Nadia Fernandez de Pinedo Echevarria, Felix Muñoz, Jin Lei, Guimel Hernandez and Wang Li. I thank reviewers and editors of this journal for their comments to improve this paper. Any errors are my own.