Most refugee movements take place between neighboring countries in the Global South.Footnote 1 Despite this, most academic work on refugee integration focuses on Western host states, leaving a gap in our knowledge of how most host states manage the complicated task of integrating refugee workers into the labor force.Footnote 2 This article uses quantitative and qualitative evidence from Jordan to show that rather than competing directly with the Jordanian labor force, a higher local concentration of Syrians is associated with increased precarity among Egyptian migrant workers. This finding reflects policy decisions taken by the Jordanian government to favor citizen interests by substituting Syrians for Egyptian laborers. Unpacking this dynamic is particularly important as host countries navigate challenging political and economic circumstances while integrating refugee populations during protracted conflicts like the Syrian Civil War.

This article contributes a fresh perspective on the integration of forced migrants into the labor market by examining how other vulnerable communities are impacted by such policies. I begin by drawing on the social science literature on migrant labor vulnerability in refugee host states. While debates about immigration and refugee resettlement have featured prominently in recent political debates, most of the literature on refugee integration is based on experiences in the Global North. I then focus on the case of Jordan and the role of Egyptian migrant labor in key labor-intensive economic sectors. Finally, I use two new data sets to test whether higher levels of Syrian laborers impact Egyptian laborers via two measures: household wealth (as a measure of economic fitness) and informality (as a measure of labor security). I found that while Jordanian household wealth and formality have not been directly impacted by a higher local density of Syrians, Egyptians in Jordan have registered higher levels of informality. These findings also speak to broader debates about the economic impact of large-scale refugee labor market integration.

Forced Migration and Labor Integration

Migration is a contentious political issue across the Global North and South. Citizens and politicians in host countries often voice concerns that immigration will increase competition for jobs and put pressure on host societies’ social safety nets.Footnote 3 The literature on refugee integration often finds, however, that incorporating refugees and other vulnerable migrants into the labor force can have positive effects on host country economies.Footnote 4 Refugee labor can fill labor market gaps, create new channels of foreign and domestic investment, and increase the production and consumer bases of the economy. Although implementing integration programs introduces short-term costs to the public budget, refugee integration is often projected to repay those costs through GDP increases in the medium to long term.Footnote 5

That said, host countries’ ability to successfully integrate refugee labor depends on several factors, including the migrant laborers’ skill content,Footnote 6 the host country's labor compositionFootnote 7 and refugee labor integration policies, local state capacity, and existing social safety nets.Footnote 8 Countries in the Global North have more developed welfare systems and higher state capacity, and thus have an advantage when it comes to integrating refugee labor. Evidence from Germany, the only northern country to accept mass refugee inflows during the Syrian crisis, suggests that refugees do not compete with German labor, although refugees themselves often struggle to find work.Footnote 9 OECD and developing countries with higher levels of informal labor or lower state capacity may, however, encounter challenges with refugee labor integration. In Turkey, for example, informal Turkish workers have found themselves in competition with Syrian refugees who are unable to find formal work.Footnote 10

Although the effect of refugee integration on host populations has been well studied, much less is known about how integration impacts established migrant communities in host countries. SociologistsFootnote 11 have criticized the migration literature for focusing primarily on western states, since most refugees are hosted by neighboring states in the Global South.Footnote 12 Developing host countries often have higher levels of informality, less robust social safety nets, and lower state capacity. As a consequence, refugee labor integration can stretch host states’ bureaucratic capacity and become politically controversial. In the Middle East and North Africa, refugee labor most directly competes with local informal workers, as well as with other migrant groups. Intraregional migrant workers have long played an important role in Middle Eastern economies, where labor has been highly mobile since the 1970s. Egyptian migrant workers in particular have filled low-skilled jobs in the construction, agriculture, and services sectors in Jordan for decades. The political exigencies of labor market reform in the face of the Syrian refugee crisis, however, have forced changes to Jordan's economic equilibrium. Specifically, the Syrian refugee crisis has negatively impacted the sizable labor force of low-skilled Egyptian workers in Jordan. These effects, measurable even before the 2016 Jordan Compact, have been more pronounced in subdistricts with higher concentrations of Syrians.

Jordan and Syrian Labor Integration

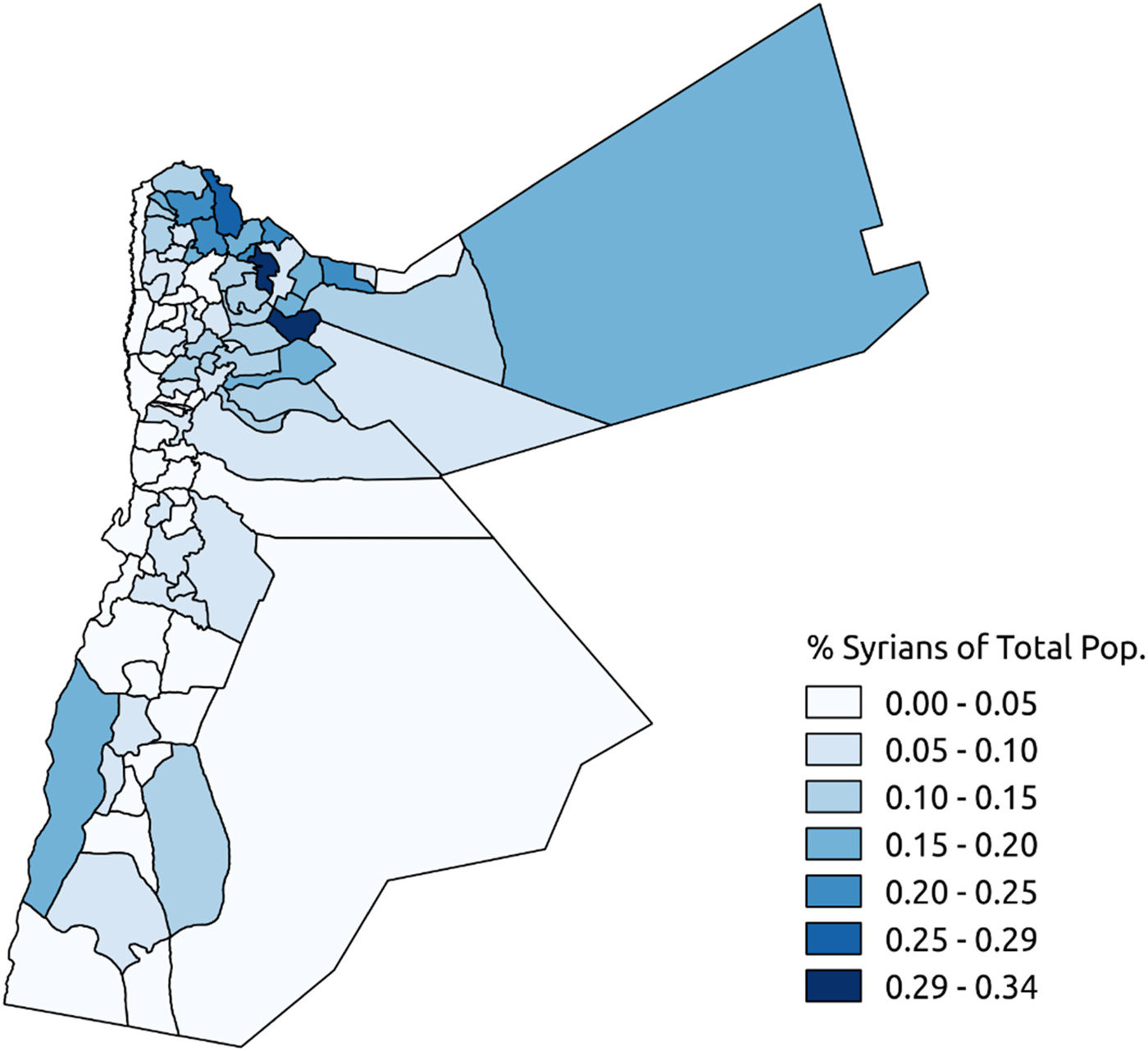

Although the Syrian refugee crisis has been framed as a European phenomenon, Jordan and Syria's other neighbors have received the largest share of refugees during seven years of civil war. This article joins othersFootnote 13 in calling for renewed attention to refugee integration in countries adjacent to conflict. Syria's neighbors are working with international donors to find new ways of alleviating the economic challenges of hosting long-term refugee populations. This is a matter of particular urgency for Jordan. The Jordanian Department of Statistics estimatesFootnote 14 that the country hosts nearly 1.3 million Syrian refugees,Footnote 15 most of whom live among host communities.Footnote 16 Figure 1 shows that, as of 2015, Syrians in Jordan were concentrated primarily in northern districts and urban areas but were also spread throughout Jordan's provinces into rural and peri-urban regions.

Figure 1: Syrians as a Percentage of Total Population in Jordan (by Subdistrict), 2015.

With 89 refugees per 1,000 inhabitants, Jordan has the second-highest per capita share of refugees in the world.Footnote 17 The Jordanian economy was characterized by slow growth and high unemployment even before the Syrian conflict, and recent protestsFootnote 18 over IMF-designed tax reforms signal the country's economic fatigue. Jordanian officials have used the influx of Syrian refugees as both a political excuse for Jordan's flagging economy and as an opportunity to negotiate more international development support.

The government of Jordan (GOJ) and international donors have introduced several policy initiatives to address Syrians refugees’ long-term residence in Jordan. The cornerstone of these is the integration of refugees into the Jordanian labor force. Among the priorities of the GOJ and donor governments is to minimize the negative impacts of Syrian integration on Jordanian citizens. To achieve this, the GOJ has prioritized issuing formal work permits for refugees in sectors that Jordanians prefer to avoid, including agriculture, manufacturing, and construction. New policy initiatives like the Jordan CompactFootnote 19 advocate for placing Syrian refugees in sectors already dominated by migrant labor.Footnote 20

The push to integrate Syrian labor has important implications for other migrant groups in Jordan. Jordan has historically used cheaper migrant labor in manually demanding sectors of the economy unpopular with Jordanians, such as agriculture or construction. Jordan's large Egyptian migrant labor force is the most vulnerable to any changes in work permits and labor migration policy. This article draws on qualitative and quantitative evidence to illustrate how this policy toward Syrian labor market integration has affected Egyptian labor on the subnational level.

Since 2016, the GOJ has been vocal about the country's limited capacity to balance citizens’ needs and support for Syrian refugees. In 2017, then Prime Minister Hani al-Mulki declared that the Jordanian government had “reached its limit” and that the refugees put unsustainable pressure on government finances, infrastructure, and public utilities.Footnote 21 Despite continued public support for Syrians and their welfare,Footnote 22 Jordanians felt their needs were being overlooked amid the refugee crisis.Footnote 23 Jordanians outside the capital, Amman, commonly associated refugee integration with increased pressure on services such as education and water, rising prices (particularly rent), social friction arising from cultural differences, and financial and employment losses for Jordanian citizens.Footnote 24 Donors and international agencies have taken note of these drivers of host community fatigue as the development response to Syrians’ tenure in Jordan has evolved from humanitarian support to sustainable integration.

The February 2016 Jordan Compact marked a turning point in the international and domestic policy response to Syrian refugees in Jordan. The compact was the first collective document that addressed host community concerns and donor priorities to employ Syrians. Prior to this agreement, Syrians were rarely issued formal work permits. As part of the negotiations, the GOJ committed to issuing 200,000 free work permits to Syrians. In January 2018, Jordan's Ministry of Labor reported that 87,141 permits had been issued since January 2016, 84 percent of which had been issued to Syrians outside the refugee camps.Footnote 25 The majority of these permits had been issued for work in construction (56 percent) and agriculture (25 percent). These sectors had historically been filled by other migrant labor groups, especially male Egyptian migrant laborers. The rest of this article will explore how the Syrian crisis has economically affected Egyptian migrant labor.

Egyptian Vulnerability: The Syrian Crisis and the Informalization of Egyptian Labor in Jordan

Egyptian laborers have been coming to Jordan since the 1970s to work in agriculture and construction. Egyptians filled the jobs left vacant by Jordanian labor migration to the Persian Gulf, filling low-wage sectors that remaining Jordanians preferred to avoid.Footnote 26 One estimate placed the Egyptian share of the agricultural labor market in the Jordan Valley, Jordan's most productive agricultural region, as high as 87 percent in 1986.Footnote 27

Egyptians continue to play an important role in Jordan's agriculture, construction, and service industries. Most migrant Egyptians live in poor conditions, with urban and peri-urban workers sharing small crowded apartmentsFootnote 28 and agricultural workers living in concrete hutsFootnote 29 they build themselves on the fields. The work is physically taxing, to the extent that some Egyptians who came to Jordan on work permits for agricultural employment “escape” to other sectors, like services or construction.

While turnover is high, Egyptians have been migrating to Jordan annually for over 30 years. Some who stay have worked their way up from farm laborer to landowner through saving and through networks built over the course of their long-term residence in Jordan. One Egyptian landowner owned land both in Mafraq and in the Jordan Valley.Footnote 30

Since the Syrian refugee crisis began, Jordanian agriculture has suffered from closed borders with its biggest agricultural markets in Syria and Iraq. The closure of the Jordan-Syrian border has also meant that these traditional migrant farmworkers, as well as other Syrian refugees, have become a more permanent fixture in the labor market. Before the crisis, migrant farming families would make annual trips to Jordan from southern Syria. Their winter migration began in the Jordan Valley and worked southward before looping back northward to the highlands of Irbid and Ajlun, ending at Mafraq's dryland farms.Footnote 31 In the midst of this challenging labor market, the GOJ implemented new rules governing migrant labor that stand to impact other low-skilled migrant groups.Footnote 32 Informal arrangements have long governed labor in Jordan's agriculture and construction industries. Pushes to formalize labor in those sectors have been used to selectively screen migrants, with Syrians now being given priority both formally and informally. The restructuring of laws and priorities leaves Egyptian migrants in Jordan more vulnerable to exploitation and deportation. Lenner and Turner (2018) summarize this quandary by underscoring the costs to Jordanian businesses of formalizing Syrian labor:

Jordan's informalized labor market relies, to a significant degree, on illegal migrant labor and the non-enforcement or selective enforcement of labor regulations. We argue that the attempts to increase Syrians’ formal labor market participation do not sufficiently take these dynamics into account. Formalization or substitution strategies run into vested interests and political sensitivities that contribute to maintaining this informal system that relies on both Syrian and Egyptian migrant labor. While they may increase the security of those Syrians who get permits through these schemes, they may well leave large parts of both the Syrian and Egyptian populations in Jordan as precarious and vulnerable as they have been before.

The next section of this article uses new data sources to explore the impact of the Syrian refugee crisis on the Jordanian labor market. In particular, I focus on how the Egyptian labor outcomes have changed between 2010 and 2016. These findings suggest that Egyptians are the most negatively affected segment of the Jordanian labor force, which is likely due to the GOJ's pressure to replace Egyptian migrant workers with Syrian refugees.

Data and Analysis

This data analysis draws on two new data sources to measure how Syrian labor impacts Egyptian migrant labor outcomes in Jordan. The first is the Jordan Labor Market Panel Survey (JLMPS). The JLMPS is the only nationally representative study of its kind in Jordan. The first wave was undertaken in 2010 prior to the outbreak of the so-called Arab Spring uprisings and Syrian mass migration. The 2010 surveyFootnote 33 captured 25,953 individuals in 5,102 households across Jordan.Footnote 34 The 2016 waveFootnote 35 surveyed 33,450 individuals, including 16,631 from the original sample. The refresher survey oversampled neighborhoods with high proportions of non-Jordanians, including Egyptians and Syrians. The nature of the refresher sampling and labor migration patterns in Jordan means that retention of Egyptians and Syrians between waves is low and precludes true panel data analysis. Comparative statistics of the two waves, however, can tell us much about changes in the labor force for Jordanians, Egyptians, and Syrians during the 2010–2016 period.

My second data source comes from an original data set measuring the number of Syrians per capita at the subdistrict level based on the 2015 Jordan Population Census results.Footnote 36 I interpret this measure as an absolute number of Syrians across Jordanian localities, but it also proxies as our best estimate of the change in Syrian population in Jordan since the beginning of the war. Although some Syrians were present in Jordan prior to the uprisings, the majority arrived as refugees after 2011. I tested whether the proportion of Syrians in respondents’ subdistricts affects labor outcomes for each national group, specifically workers’ household wealth and informality status. The analysis shows that Egyptians have been more negatively affected by Syrian labor entrants than local Jordanians have been based on measures of informal labor market participation.

Nationality was my key independent variable of interest, and I was particularly interested in how outcomes for groups varied between the 2010 and 2016 waves of the JLMPS. These models looked at Jordanians, Egyptians, and Syrians of working age (15–65 years old) to determine differences between these labor groups between 2010 and 2016. Jordanians were the baseline category in all regressions. In each model, I controlled for age, sex, education level, sector, and governorate.

I began my analysis by looking at baseline household wealth and formality patterns. To measure respondents’ economic well-being, I used the JLMPS household wealth score as a proxy for standards of living and spending power. Household wealth was a continuous variable comprised of measures of housing quality (e.g., walls, floors) and the number of durables (e.g., refrigerators, smartphones, televisions, rooms, etc.) recorded per household in the survey. The second outcome was the formality of respondents’ jobs. Formality is a binary variable where 1 indicates formal employment. Formal employment must be registered with the state, either through licensing or social security, which is available for citizens and foreigners alike, or through holding a valid work permit, for non-citizens only. Formal work is more stable, pays better, and has more benefits than informal employment.

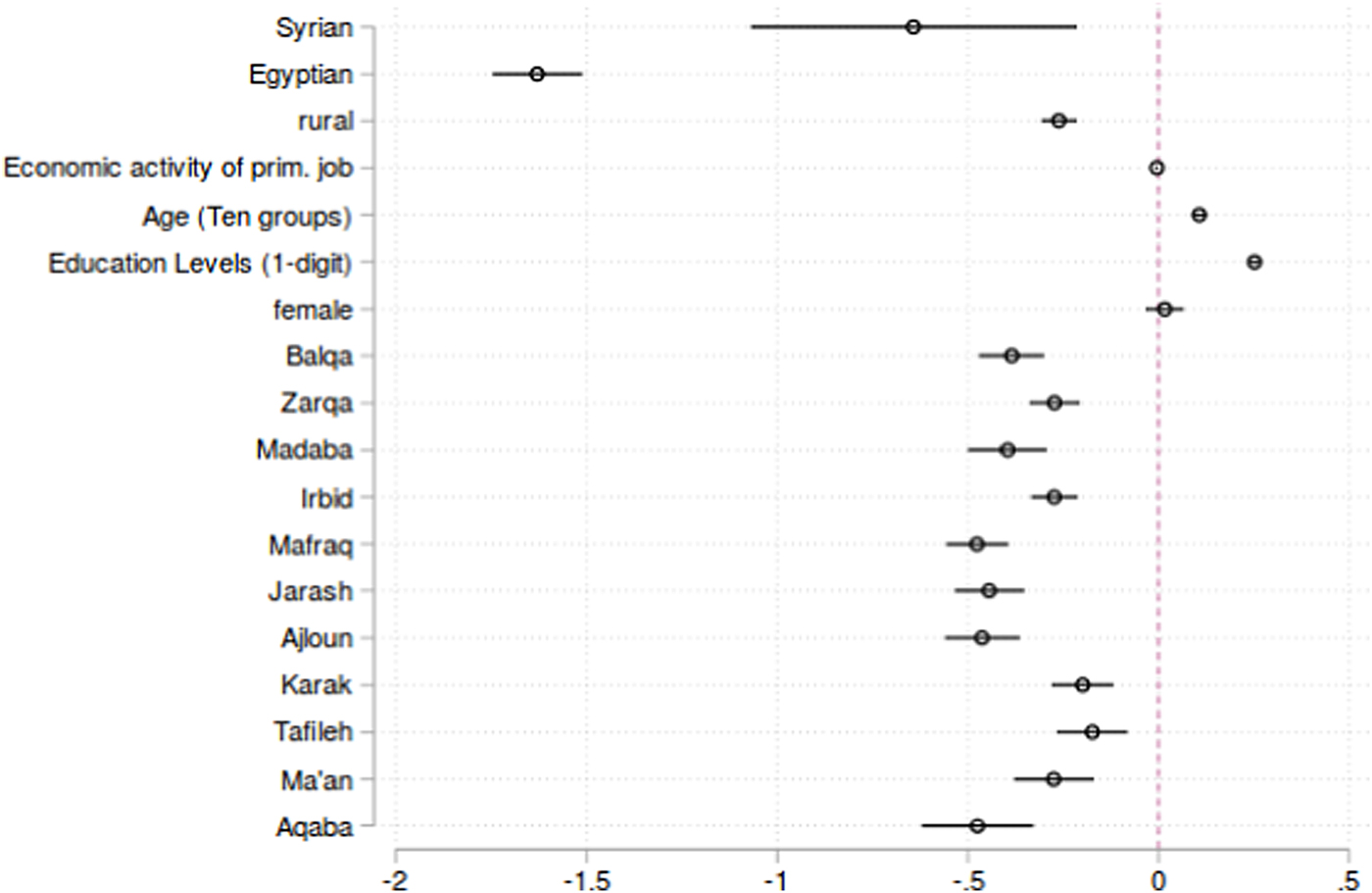

In 2010 and 2016, both Syrians and Egyptians reported lower levels of household wealth than did Jordanians [Figures 2 and 3]. In 2010, household wealth for Syrians in Jordan was higher than it was for Egyptians. In 2016, Syrian household wealth was significantly lower than in 2010 and was only slightly higher than the reported wealth for Egyptians. This makes sense, given the fact that the majority of Syrian workers accept wages that are much lower than their Egyptian counterparts. In both waves, older workers and those with more education reported higher levels of wealth, all else equal, while rural respondents were less wealthy than their urban counterparts.

Figure 2: Household Wealth, 2010 (Ordinary Least Squares, OLS).

Figure 3: Household Wealth, 2016 (OLS).

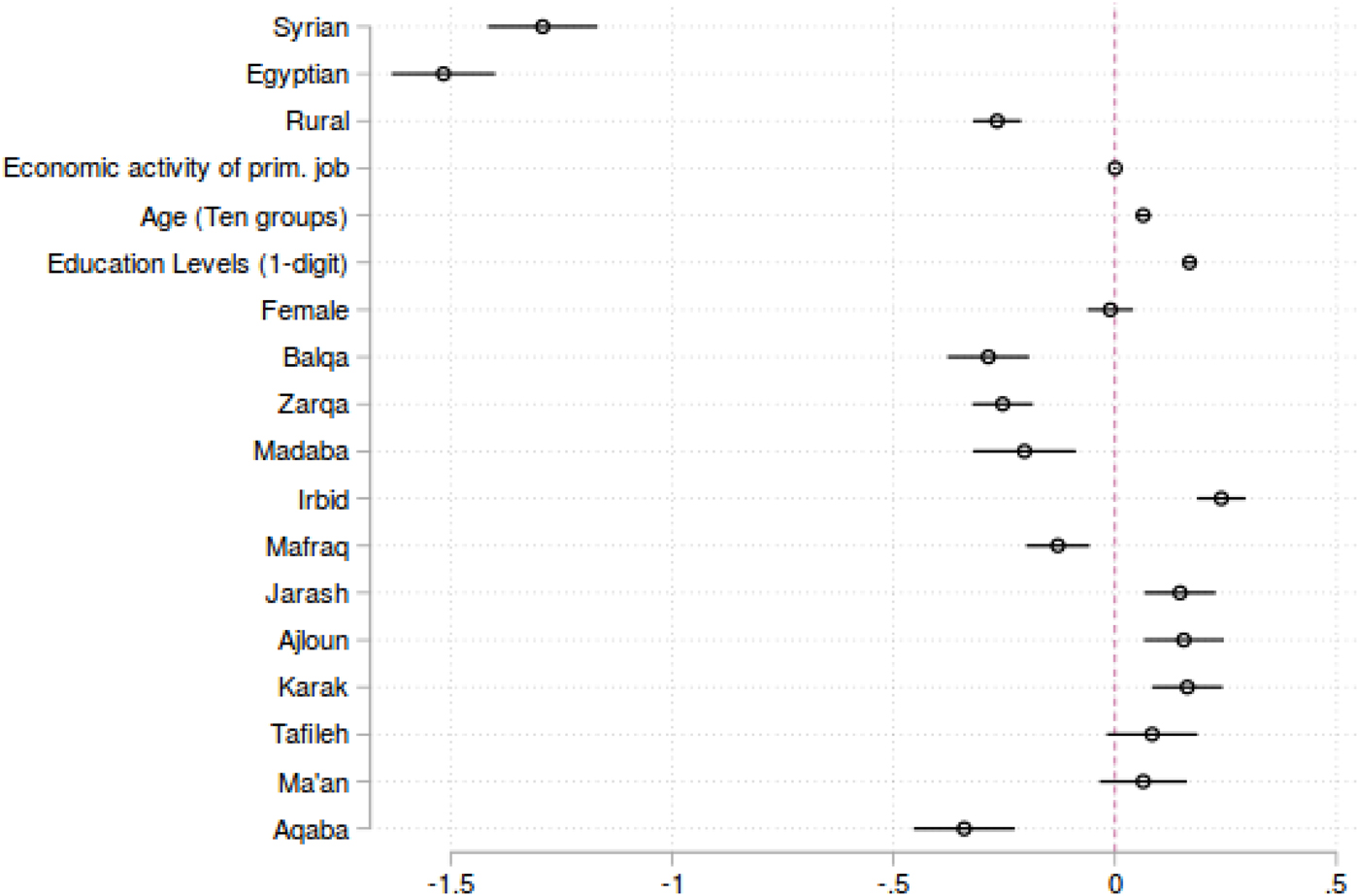

Formality levels for Syrians and Egyptians relative to Jordanians appear to have changed little in the baseline models [Figures 4 and 5]. Across the 2010 and 2016 waves, both migrant groups were more likely to be informally employed than Jordanians, with Syrians being more likely than Egyptians to work informally.

Figure 4: Formality, 2010 (Logistic Regression, Logit).

Figure 5: Formality, 2016 (Logit).

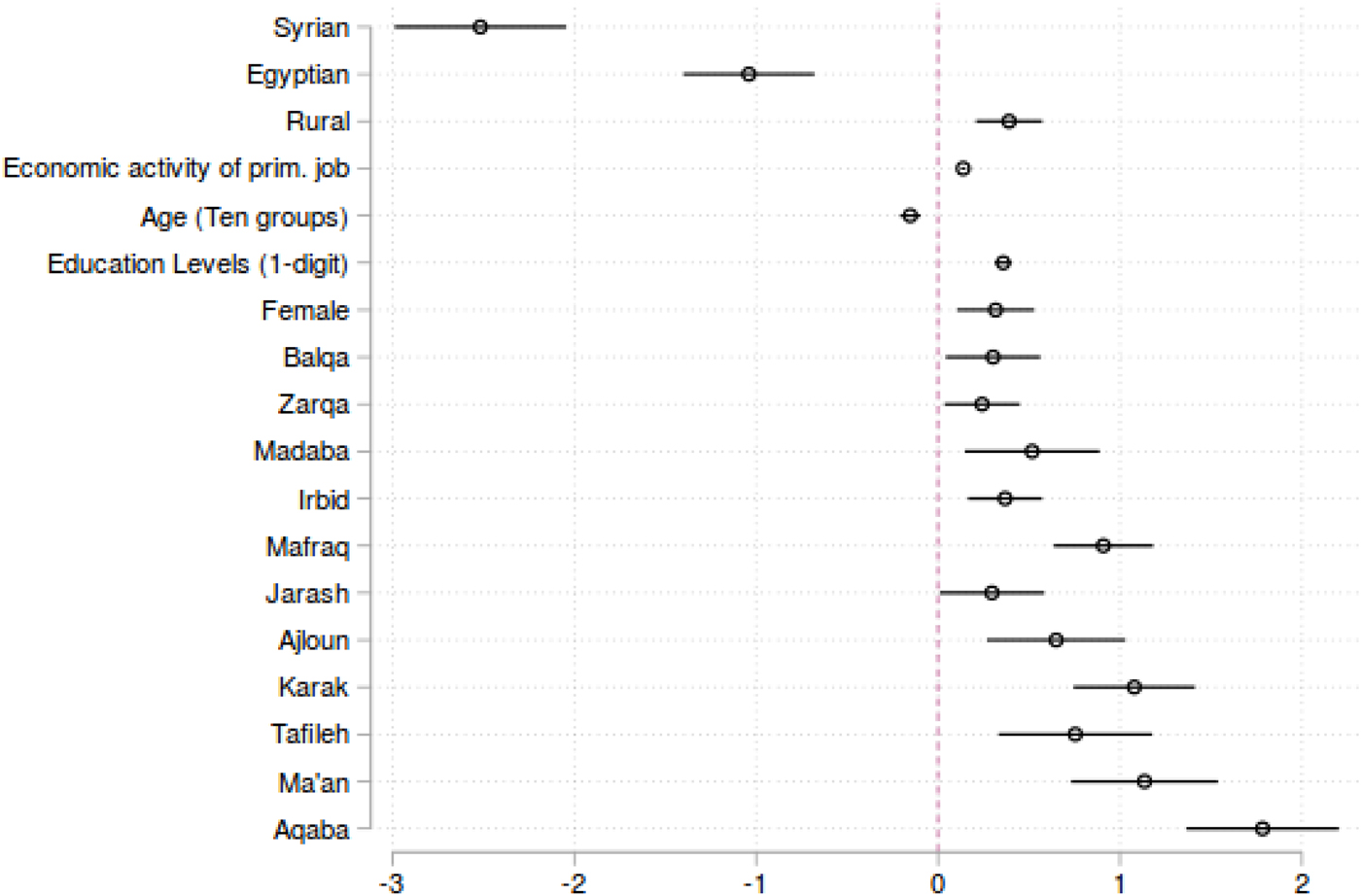

This picture changes, however, once we account for the proportion of Syrians among the total local population. Figures 6 and 7 show the 2016 baseline regressions with the addition of an interaction term between respondents’ nationality and the proportion of Syrians in their subdistrict. For Syrians, however, there was a significant and positive effect on household wealth compared to Jordanians for having more Syrians in their subdistrict, while for Egyptians there is no effect.

Figure 6: Effects of Nationality and Local Syrian Population on Household Wealth, 2016 (OLS).

Figure 7: Effects of Nationality and Local Syrian Population on Formality, 2016 (Logit).

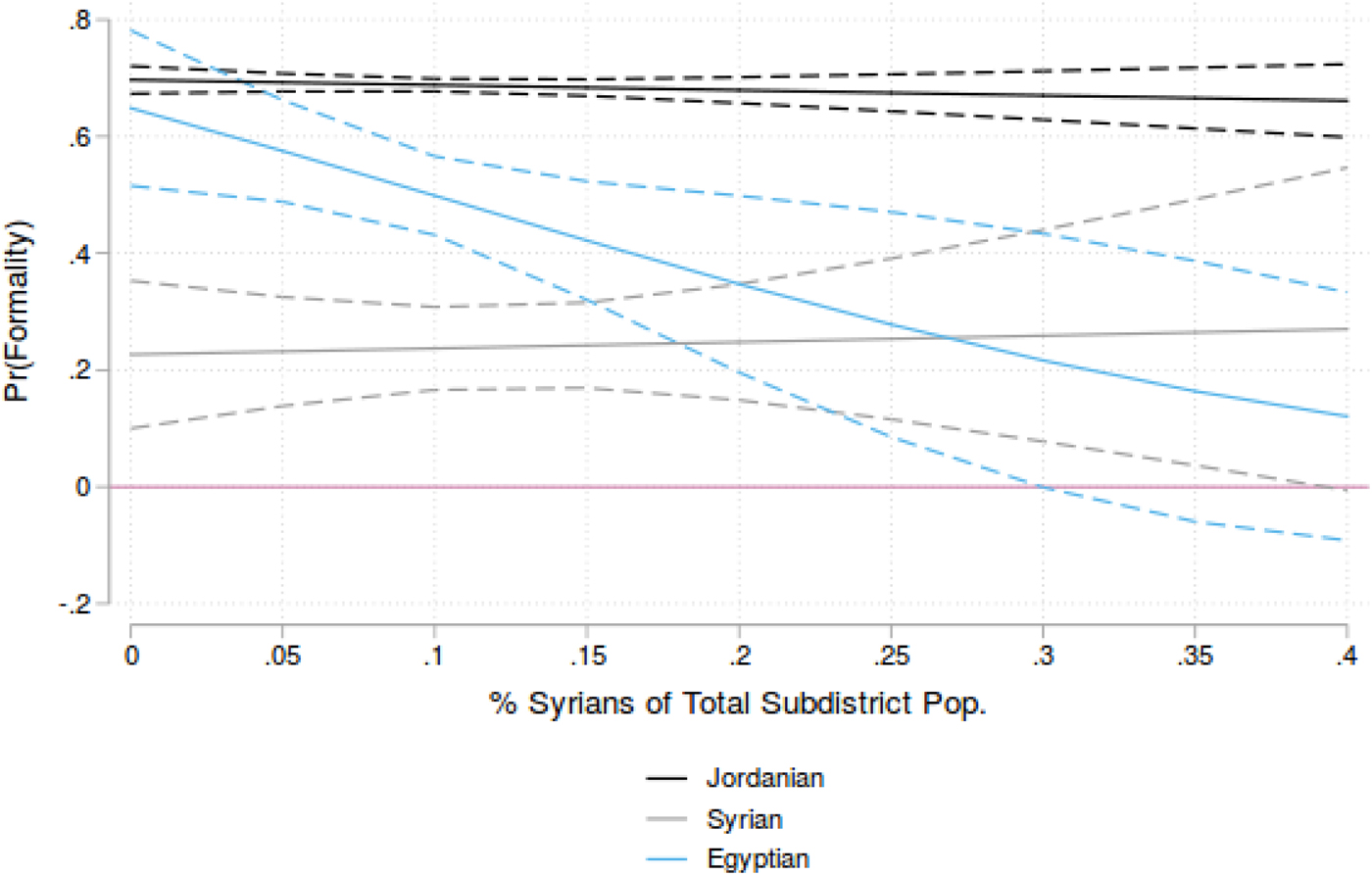

The interactive logistic models for formality suggest that a higher proportion of Syrians in a given subdistrict in 2016 correlates to lower formality among Egyptians [Figure 7]. The probability of being an Egyptian formal worker decreased as the percentage of Syrians in the subdistrict rose [Figure 8].

Figure 8: Marginal Effects of Nationality and Local Syrian Population on Formality, 2016 (Logit, 95% confidence intervals).

The politics surrounding Syrian refugees in Jordan means that creating work for Syrians in Jordanian-dominated sectors is not a viable option. As a consequence, the most convenient avenue for Syrian labor integration is to employ refugees in sectors dominated by other migrant groups. A large body of qualitative evidence corroborates this finding.

Changes in formal policy are pressuring Egyptian laborers from multiple angles. Economically, the downward pressure on wages due to Syrian acceptance of lower compensation makes the high costs of formality almost impossible to meet. Egyptians are politically pressured, however, to formalize. Labor law reforms following the Jordan Compact have been designed to shrink existing migrant populations to make room for Syrian workers. Enforcement of work permit rules on Egyptians has been on the rise, with many Egyptian migrants being either deported or prevented from entering since 2016.

The costs of formality for Egyptians are much higher than for Syrians. Work permits are free to Syrian refugees but can cost upward of 1,000 Jordanian dinars for Egyptians (including costs borne in Egypt before travel).Footnote 37 Egyptians are being forced into the informal sector by economic necessity so that they effectively compete with Syrian laborers, who work for lower wages. Many Egyptian agricultural workers, for example, are working double days. They complete one full shift in the morning in the Jordan Valley before being trucked to highland farms to work another full workday in the afternoon.Footnote 38 Without formal work permits, migrant laborers are in a precarious position, as foreign workers can be arrested and deported.

One alternative explanation for the formality of Egyptian laborers is their physical location. If Egyptians are shifting from rural to urban employment, GOJ enforcement of work permits and formalization might be higher in cities (where most Syrian refugees live) and partially explain the findings. The models are robust to location, and the coefficient for being a rural worker correlates positively to being a formal worker, providing some evidence that it is not the location, but rather the proportion of Syrians in the local labor force driving the results.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that the GOJ's integration policies regarding Syrian refugees primarily impact other migrant labor groups. On the one hand, this suggests that the Jordan Compact's implicit intention of prioritizing Jordanian labor has been successful, at least insofar as jobs have not been taken away from Jordanian workers. On the other hand, the evidence presented here suggests that the Jordan Compact is introducing profound changes to a decades-old labor market equilibrium founded primarily on informality and cheap migrant labor.

This raises several questions about the nature of MENA migrant labor flows and the structure of domestic economies. The first pertains to the long-term ramifications of dismantling the Egyptian labor force in Jordan's low-skilled sectors. When the Syrian conflict ends and refugees have the option of returning home, how many will continue to work for low wages in Jordan's most challenging and unsafe sectors? Although the timing and the process of ending the conflict in Syria remain matters of conjecture, the forced reduction of the Egyptian labor force combined with a potential repatriation of Syrian refugees means that the Jordanian agriculture and construction industries may face a labor shortage.

Second, what do these findings suggest about Egyptian migrant labor flows across the region? Egypt is the MENA region's largest labor exporter, and remittances play an outsized role in the domestic economy. Egyptian remittances have risen fast since the early 2000s: Egyptian migrant workers remitted $5.02 billion in 2005, a figure that had grown to $22.52 billion by 2017. Both educated and unskilled Egyptian workers pursue opportunities abroad to send money back to their families. In the Gulf, a popular destination for educated Egyptian labor, workers have found themselves victim to politicized labor practices in host countries. In June 2017, for example, Egypt and a number of Gulf countries accused Qatar of supporting terrorism and interfering in their domestic politics. All four countries issued a complete boycott on Qatar. The move called the immigration status of some 350,000 Egyptian migrant laborers into question,Footnote 39 and in 2018 the Qataris began deporting Egyptians.Footnote 40 Unlike in Jordan, where the politics of labor substitution are underpinned by domestic interests and a local supply of Syrian refugees, the Qatari case shows how international politics in the region can also impact migrant laborers before the domestic workforce. As regional alliances change and the Gulf countries alter their spending patterns, decades of intra-regional migrant labor might be coming to a close. Given the prevalence of migrant labor in the region, the precarity of migrants’ status in host countries presents serious issues both for Egyptians who send money home and for Egypt's delicate political situation as they may have to absorb returnees for whom there are no jobs. In 2011, remittances accounted for 6 percent of Egypt's GDP,Footnote 41 suggesting that the loss of remittance income would have serious implications for Egypt's domestic economy.

In sum, this study corroborates findings in other contexts that suggests that refugee labor integration does not harm host country labor. In Jordan, this is because refugees and citizens are not competing for the same jobs. Instead, Syrian refugees are displacing other migrant groups in low-paying, high-risk sectors. In the medium to long term, the consequence of Jordan's politicized refugee crisis is that policymakers are replacing one vulnerable group with another without making true progress in addressing the deep structural issues of the Jordanian labor market.

Appendix: Regression Tables

Table 1. Household Wealth and Informality, 2010

Table 2. Household Wealth and Informality, 2016

Table 3. Local Percentage of Syrians and Household Wealth and Informality, 2016