Introduction

The legitimacy of interstate hierarchical rule in the security sphere is based on a social contract. The subordinate state desires a political order that mitigates the insecurity of the ‘state of nature’. The dominant state provides this security, in exchange for which the subordinate state partially relinquishes its sovereignty.Footnote 1 David Lake argues that policymakers in subordinate states base decisions on whether to enter into hierarchical relationships on rational assessments of the relative qualities of the political order being offered to them.Footnote 2 But how are they able to assess how well a particular order meets their needs? Lake’s theory cannot help us much here. It simply assumes that state leaders are able to decide on the quality of any proposed order. Appraisals of the relative qualities of an international political order, however, are bound to be contingent and as such an arena for contestation. Analyses of how knowledge is generated lay bare relations in arguably the most fundamental form of power – the power to shape understandings of reality.Footnote 3 Instead of bracketing the knowledge-producing processes through which policymakers in subordinate states make an assessment of the quality of a political order, we should consider such processes in our explanations of the emergence and continuation of international hierarchies.

This article does this by highlighting the role of an ‘epistemic community’ of security experts in sustaining the remarkably persistent East Asian support for the region’s hierarchical international order led by the ‘non-regional’ US. The uncertainty of complex international politics has been identified as the key condition for expertise influencing decision-making.Footnote 4 By pointing out natural friends, collective identification with other actors can alleviate the inherent uncertainty in choices about alignment politics. When the sense of common belonging in an international context is thin, however, uncertainty persists. In addition, a relatively peaceful international environment paradoxically increases uncertainty, since it provides decision-makers with few reality checks against which to evaluate the costs and benefits of existing and candidate political orders. Both of these conditions – a low level of interstate identification and relative peacefulness – are present in East Asia. Latent regional uncertainty is thus present, which favours the potential impact of security expertise.

When East Asian policymakers articulate their support for the US-led regional hierarchy, they tend to draw heavily on a cause-and-effect claim about the workings of international security: US military supremacy is the indispensable guarantor of regional ‘stability’. This ‘stability belief’, however, is plagued by a number of ambiguities, deficiencies, and uncertainties; the analytical merit of the belief fails to live up to its immense popularity. The article explains the popularity of the belief by focusing on the politics of expertise behind its constitution as an authoritative knowledge claim. I identify the individuals who seem most influential in naturalising the stability belief – a transnational and multidisciplinary network of experts on international security conceptualised as ‘The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community’, or TAPEC for short. By internalising the stability belief, providing it with epistemic authority, channelling it into policymaking circles and, in some cases, making policy themselves, TAPEC members help to convince East Asian policymakers that the current US-led social order is the best choice for maintaining national and regional security. Expertise should thus be added to ‘charisma, tradition, and social norms’Footnote 5 as a potentially critical source of the authority that make states accept subordinate roles in international hierarchies. The epistemic community concept, moreover, is suggested as a general explanation of how expertise on international security is created. The concept is well-suited to capturing contestation and change in the field of security expertise, which are likely to become increasingly important if emerging states attempt to challenge US-led hierarchical regional orders.

China’s rise in East Asia might represent the most important challenge to the current US-led international hierarchy. However, none of the steadily expanding scholarship on a possible East Asian ‘power shift’ from the US to China has thus far recognised the important power resource that TAPEC represents,Footnote 6 probably contributing to a tendency to underestimate the resilience of US regional leadership. The extent to which international authority also depends on security expertise in other regions will be a critical area of research for students of international hierarchy.

Sections 2 and 3 present and critically discuss the stability belief. The epistemic community concept and its role in international hierarchy are developed in section 4 and section 5 conceptualises TAPEC. The concluding section sets out the study’s contribution.

The epistemic authority of the stability belief

Around half the world is subject to US-led hierarchy in either the economic or the security sphere.Footnote 7 Lake combines two indicators in an aggregate measure of security hierarchy in dyadic state relationships: (a) the dominant state’s troop presence in the subordinate state (more troops equal more hierarchical relations); and (b) the subordinate state’s number of independent alliances (fewer alliances equals a higher level of hierarchy).Footnote 8 Security hierarchy is measured on a scale ranging from anarchic relations (no hierarchy) to protectorate relations (maximum hierarchy).Footnote 9 In East Asia, six formal and de facto US allies – Australia, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand – have forfeited so much authority over their own security policies that they can be understood as subordinate states.Footnote 10 When justifying their support for the US-led security hierarchy, policymakers in these countries – as well as those in other regional states that welcome the US presence, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam – seem generally to differ from their European counterparts by relying less on appeals to common values or belonging. Instead, they tend to emphasise the knowledge claim that the US provides regional stability.Footnote 11 See, for example, the announcement by Japan’s government that its alliance with the US is ‘indispensable … to the peace and stability of the region’Footnote 12 and the statement by Tony Tan, the minister responsible for Singapore’s defence in 1995–2005, that ‘Singapore believes that the presence of the US military … contributes to the peace and stability of the region. To that extent, we have facilitated the presence of US military forces.’Footnote 13

These official statements are mirrored by academics. For instance, the major scholarly debate on East Asian security in the past two decades has been concerned with how China’s growing capabilities will affect its foreign policy. Somewhat simplified, this discussion is divided according to whether China is thought to be a ‘status quo’ or a ‘revisionist’ power. Members of these two camps are often at loggerheads, but the vast majority tends to agree that the presence of the US military is necessary for regional stability.Footnote 14 The same broad acceptance of the stability belief is present in many other active debates on East Asian security, such as those on Japan’s current foreign and security policy trajectory,Footnote 15 US alliance politics,Footnote 16 and the prospects for regional peace.Footnote 17 Not every participant in these and other influential debates subscribes to the stability belief, but none of the major positions tend to question it seriously. While some accounts suggest alternative factors that facilitate regional stability, few leading scholars openly dispute that the US military presence is a necessary component. The epistemic authority of the belief would be challenged if ideas that explicitly contradict it – such as the claim that great power retrenchment from overseas commitments generally takes place without causing wars – were to become widely accepted. At present, however, similar views hold relatively little sway in the expert discourse on East Asian security.

To illustrate how actors in policy debates draw on the authority of the stability belief in practice, in 2010 the Australian professor and former official Hugh White tried to convince his compatriots that their government ‘should try to persuade the US that it would be in everyone’s best interests for it to relinquish primacy in Asia’.Footnote 18 The Liberal Party MP Josh Frydenberg retorted, ‘Such a major policy reversal would be a disaster for Australia and the region. … A US that is politically and militarily anchored in the region is best able to influence outcomes that are consistent with the region’s long-term stability.’Footnote 19 Labour Party MP Michael Danby, think tanker Carl Ungerer and adjunct academic Peter Khalil agreed, ‘The principal counterweight to Chinese hegemony in our region is the US and its system of alliances … . It is in Australia’s most vital strategic interest that the US presence in our region is not weakened or undermined.’Footnote 20 Both previous Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and opposition leader Tony Abbot also relied on the stability belief for their rationale when refuting White’s argument.Footnote 21 The belief also travels beyond discussions strictly confined to East Asia. For example, in refuting advocacy of US retrenchment from its overseas commitments in general, Stephen Brooks et al. seek to garner support by drawing attention to the fact that among ‘regional expertise’ on East Asia, ‘pessimism regarding the region’s prospects without the American pacifier is pronounced’.Footnote 22

The authority of the stability belief becomes even more evident when scholars fall back on it to override the customary implications of general theories of international politics. For balance-of-power realism, a weaker US presence would seem to enhance regional peace, since a decreased power gap with China would produce more balanced power dispersion between the region’s two main poles. Nonetheless, many self-professed balance-of-power theorists deny this supposedly universal logic and argue that a smaller power gap between the US and China would instead threaten peace – a view that is closer to power-transition theory.Footnote 23 This contradiction is also found among policymakers. For instance, the self-professed realist Nagashima Akihisa, a former Vice-Minister of Defense (2009–10) and Prime Minister’s Special Adviser on Foreign Affairs and National Security (2011–12) in Japan, justifies his proposal for a strategy that amounts to increased bandwagoning with the US as being based on the maxims of balance-of-power theory.Footnote 24

Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye famously argued that realist theories on the balance of power were of limited use in explaining state interactions under conditions of complex interdependence.Footnote 25 Post-Cold War East Asia witnessed a sharp and steady increase in transboundary economic interactions and multilateral institutional development. Liberal International Relations (IR) theory would expect this to facilitate a redefinition of national interests towards peaceful dispute management, even without a hegemon enforcing compliance. So why does the region need a foreign military power to ensure its peace? John Ikenberry explains this by turning the causal logic of liberal theory on its head – it is not interdependence that takes on the explanatory power as a pacifier, but US military preponderance that guarantees interdependence.Footnote 26 East Asia’s interdependence, and thus its peace, would be jeopardised if the US military retrenched. Nye himself has also argued that a withdrawal of US forces would propel East Asia towards ‘normal balance-of-power politics’ that ‘would likely lead to a regional arms race’.Footnote 27

I do not suggest that these particular analyses are influenced by the proper names of the state actors under discussion. Indeed, theoretical fidelity should arguably not be allowed to override one’s assessment of the particularities of the empirical case under consideration. It is nonetheless rather conspicuous that two of the most widely used factors to explain systemic peace in the IR literature – power balancing and interdependence – are practically absent from the debate on East Asia. The peace in this region is instead close to uniformly explained as ultimately depending on the preponderance of US military power.

Ambiguities and deficiencies of the stability belief

Arguments in favour of the US presence often employ the term ‘stability’. As a description of a pattern of interactions in a state system, this term has taken on the same two distinct meanings as Dina Zinnes once associated with ‘balance of power’.Footnote 28 Stability can mean the absence of violent conflict, but it can also point to an unchanged status quo. These dissimilar meanings are frequently confused in the debate on East Asia, which results in a tendency to adopt ‘unchanged status quo’ as both the independent and the dependent variable in the same explanation. For example, Evelyn Goh claims that the US-led order stabilises the region, while at the same time describing the period 1970–90, which as is well known a few years in saw the beginning of a lengthy and more or less uninterrupted decrease in the number of battle-related deaths,Footnote 29 as the least stable period in post-war East Asia.Footnote 30 According to John Ikenberry, moreover, ‘the hub-and-spokes system of alliances has provided for remarkable region-wide stability despite the bloody wars inside Korea and Vietnam’.Footnote 31 Since these authors do not equate stability, their explanandum, with ‘peace’, they must be assumed to take it to mean ‘unchanged status quo’, which also happens to be their explanans. As an example of an analogous argument using a different vocabulary, Park Jae Jeok argues that ‘the hub-and-spoke alliance system serves as a hedge against the possibility that regional multilateralism … becomes detrimental to the current US-led regional order’.Footnote 32

The repeated usage of stability as a catch-all term harms its conceptual resonance as an analytical tool. It is often unclear what people mean when they argue that the US guarantees East Asia’s stability. While the above examples come from scholars, there is little reason to suppose that other security experts – such as journalists, pundits, and policymakers – are better equipped to tell the meanings of stability apart. It would thus not be far-fetched to assume that some experts have come to accept the stability belief as true without formulating a conscious and precise definition of the term. When I talk about the stability belief as a social fact, therefore, I take it to cover also incoherent conceptions. That is not to say that every use of the stability belief is conceptually ambiguous. It is possible to construct a fairly coherent argument that the US facilitates regional peace (or ‘stability’) by preventing the emergence of latent security dilemmas. It does this in particular by taking the main role in impeding one or more of the ‘three vices’ of potential regional unrest: Chinese expansionism, Japanese remilitarisation and North Korean nuclear aggression.Footnote 33 This argument could find support in hegemonic stability theory, which posits that unipolar orders are likely to be both peaceful and durable.Footnote 34

The argument seems to have an obvious intuitive advantage: there has been a correlation between the US military presence and relative peace in East Asia since the 1980s. If we go back to the longer Cold War, however, there was in fact a positive correlation between the strength of US hegemony and interstate violence in the region.Footnote 35 Moreover, the extent to which the pacifying effects of transboundary commercial interactions are derivative of and dependent on US hegemony is also unclear.Footnote 36

In addition, if the relative peace in East Asia is hypothesised to be the result of the US-led order, tensions and conflicts must also be considered to be possible features of this order. There are a number of quite plausible arguments that the US presence might inflame the very same developments it is said to prevent. First, China’s rapid armament in recent decades – which many regard as the major threat to regional peace – can at least partly be understood as an attempt to decrease the military capability gap between it and the US and its allies.Footnote 37 Second, in sharp contradiction to the argument that the US-Japanese alliance works as a ‘cap in the bottle’ of Japanese remilitarisation, Washington has for many years persistently and with increasing success urged Japan to enhance its military resources and means.Footnote 38 Third, North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme could be seen as a rational pursuit of a credible deterrent against the perceived threat of a US nuclear attack and/or attempt at regime change.Footnote 39 Finally, there is compelling evidence that Japan’s alliance with the US has on several occasions served to restrict its ability to qualitatively improve its tense bilateral relationship with China, sometimes as a direct result of US interventions to prevent a loss of control over its ally.Footnote 40

Evidence of the stability belief from outside contemporary East Asia is not conclusive. The argument that a hegemonic power is necessary to provide public goods can be challenged on logical grounds,Footnote 41 as well as by pointing to the experience of European integration in the past seventy years. A comparative study of great power decline since 1870 suggests that retrenchment from overseas commitments is unlikely to embroil a declining great power in militarised disputes.Footnote 42 However, to my knowledge there has been no systematic study of how retrenchment affects security competition in the abandoned region. Moreover, to the extent that a rising power is dissatisfied with its international standing, power transition theoryFootnote 43 and status theoryFootnote 44 would predict deferential retrenchment of other great powers from the rising power’s home region to make it more cooperative. As for balance-of-power theory, an empirical test of cross-regional data from the past 2,000 years finds hegemony, rather than balancing, to be the more likely systemic outcome.Footnote 45 If this finding also applies to regional subsystems, balancing dynamics should be expected to be a limited outcome of great power retrenchment. Due to far-reaching normative, trade-related, and military technological changes, furthermore, the incidence of interstate war has fallen sharply over the past two-thirds of a century. Theoretical expectations based on historical comparisons might thus err on the pessimistic side regarding the chances of military conflict. Recent decades contain some events that arguably countervail the stability belief. Brazil’s rise in South America has not led to balancing dynamics, despite the absence of a stabilising outside power in the region. The Russian retrenchment from Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s did not bring much immediate international security competition. In the past decade, Russia has become more aggressive in its near abroad despite the steady expansion of the US-led hierarchy in Europe.

Even without fully accepting all of these objections and counterarguments, together they should make the stability thesis less persuasive than what a majority of observers take it to be. At the very least, it seems extremely difficult to decide with any certainty whether the net effect of the US military presence alleviates, aggravates or does not substantially affect the likelihood of regional conflict. While it is an untested hypothesis that a US withdrawal would not exacerbate security dilemmas, the same is true of the opposite argument. It is telling that some of the most articulate advocates of the proposition ultimately couch their support in terms of preferring ‘the devil we know’ over an alternative unknown regional security arrangement.Footnote 46 With such intrinsic uncertainty, the question of how East Asian policymakers have come to be so unwavering in their confidence that US hierarchy has a stabilising effect must be said to remain unanswered.

How, then, do policymakers ‘learn’ that the stability belief is far more credible than alternative ideas? Who ‘teaches’ them that it is an authoritative knowledge claim? In order to analytically construct this agency, four traits seem to be especially relevant. First, the stability belief is a causal knowledge claim. We are therefore looking for people with recognised expertise on international security, not for activists primarily driven by principled beliefs.Footnote 47 Second, the experts reproducing the belief are found in many countries. A focus on national fields of expertise in isolation could miss potentially crucial transboundary linkages.Footnote 48 Third, they are active within several occupations. The network thus differs from a transnational ‘guild’ of professionals.Footnote 49 Finally, most of the experts are not state representatives. We are not therefore seeing a ‘government network’ in action.Footnote 50 Taking all of these points into consideration, the ‘epistemic community’ concept seems well suited to capturing the agency involved.

Epistemic communities and international hierarchy

In international politics, transnational as well as linguistic and politically bounded epistemic communities (epicoms) – ‘network[s] of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area’Footnote 51 – arguably play essential roles in the wider policymaking process in many issue areas. Various kinds of experts make up epicoms – not just natural scientists.Footnote 52 The members of an epicom share causal and principled claims, notions to validate their causal claims and a policy enterprise that stems from their common professional competences.Footnote 53 Their causal knowledge claims do not have to be objectively true. What is relevant, for claims about the natural and social world alike, is that community members and their audience believe them to be true.Footnote 54 A group of experts sharing a set of professional attributes is not necessarily an epicom. For example, the nuclear arms control epicom that emerged during the early Cold War did not include all nuclear security experts. Those who advocated either disarmament or military superiority, in particular, were not members since they departed from the community’s causal and normative beliefs and its policy project.Footnote 55 Gathering a large share of the experts on an issue should be expected to increase an epicom’s potential influence.

The complexity of international politics leads to intrinsic latent uncertainty, which has been identified as the key condition that favours policymakers turning to epicoms for expert solutions.Footnote 56 Unexpected turn of events can further increase uncertainty.Footnote 57 For policymakers considering the costs and benefits of different international political orders, moreover, two additional conditions should be anticipated to augment uncertainty. A first condition is a low level interstate identification. By blurring the perceived boundary between the self and the other, identification distinguishes trusted friends and thus mitigates uncertainty.Footnote 58 Limited identification, therefore, should be expected to increase uncertainty. A relatively peaceful international environment is a second condition, as it provides few reality checks against which to evaluate knowledge claims about international security. This favours the reliance on experts’ counterfactual reasoning based on close familiarity with general theories and empirical conditions.Footnote 59

Epicoms are not just passive providers of expert advice. They proactively use their cognitive authority to influence policymakers’ decisions on what constitutes a problem, for example, in the security sphere, by framing issues as requiring management by extraordinary means.Footnote 60 Epicoms are thus not the functional instruments of states, but exercise power independently. Nor is their influence limited to persuading policymakers in a direct causal manner. It also involves producing the background knowledge that underpins social action.Footnote 61 Hence, ‘the capacity to both “construct” and “naturalize” the social world by imposing certain categories, models and conceptual schemes is a central part of the power of expertise’.Footnote 62 Epicoms are themselves partly constituted by practices of reified background knowledge. Thus, while the approach is agent-focused, epicoms can be said to constitute ‘communities of practice’.Footnote 63 Research has highlighted the role of epicoms in achieving policy change, but they can also uphold policy continuity by providing authoritative legitimisation for existing arrangements. An epicom’s ideas can turn into orthodoxy if they become institutionalised in national bureaucracies and international organisations. However, internal coherence regarding a community’s key beliefs is crucial to maintain its influence.Footnote 64

Much empirical work treats epicoms as highly cohesive groups – with comprehensive interpersonal ties and a strong ‘we-feeling’. However, these properties are not implied in Peter Haas’s initial concept formation, which sets the course for the research programme. Apart from the main criteria presented above, the complementary definitional features of epicoms all denote common beliefs, values and intentions, rather than interpersonal cohesion or collective identification.Footnote 65 Haas is also clear that the members of an epicom do not need to ‘meet regularly in a formal manner’.Footnote 66 The looser requirements of social cohesion were further reinforced when he likened epicoms to Ludwig Fleck’s ‘thought collectives’ and Thomas Kuhn’s ‘paradigms’.Footnote 67 The agent-centredness of the epicom approach gives rise to a ‘boundary problem’, of how to isolate members of an expert community from other actors in their social context.Footnote 68 Presenting clear evidence for how members meet the community’s analytical criteria mitigates this problem.

Analysing the role of epicoms involves a number of tasks:Footnote 69 (i) ‘identifying community membership’; (ii) ‘determining the community members’ principled and causal beliefs’; (iii) ‘tracing their activities’; (iv) ‘demonstrating their influence on policymakers at various points in time’; (v) ‘identifying alternative credible outcomes that were foreclosed as a result of their influence’; and (vi) ‘exploring alternative explanations for the actions of decision makers’. Moreover, the literature thus far has arguably been quite weak at analysing epicoms in relation to the knowledge-political contexts in which they exist, including how their influence compares to that of other actors.Footnote 70 Partly as a solution to this problem, epicoms have been situated within field theory.Footnote 71 The field concept is a way to capture patterns of social power struggle. Fields are ‘structured spaces that are organized around specific types of capital or combinations of capital’.Footnote 72 ‘Capital’, moreover, are the material, cultural, social or symbolic power resources that ‘become objects of struggle as valued resources’.Footnote 73 The specific fields in which epicoms operate are structured around struggles for the symbolic capital of that which constitutes valid knowledge.

The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community and US-led security hierarchy in East Asia

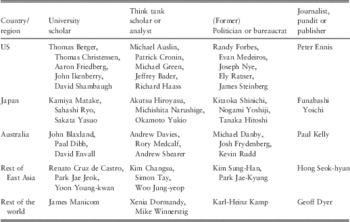

Through an inductive review of knowledge-generating discourses on and practices in East Asian security, I have identified the individuals who seem to be primarily responsible for reproducing the stability belief as an authoritative knowledge claim. These people, who comprise a transnational and multidisciplinary network of socially recognised experts on East Asia’s international security, are here conceptualised as ‘The Asia-Pacific Epistemic Community’. Community members share the causal knowledge claim that the US military stabilises East Asia, or the stability belief. TAPEC members see the US military as a necessary, although not necessarily sufficient, factor in regional stability. By safeguarding regional stability, the US military presence is perceived to be serving not only the US national interest, but also the interests of the region as a whole. TAPEC’s normative claim is that since stability is a good thing, the US should maintain, and preferably strengthen, its security leadership in East Asia for the foreseeable future. TAPEC members thus see the US as an integral part of the ‘Asia-Pacific region’, and this norm is what gives the community its name here. Flowing from these claims, TAPEC’s policy enterprise is to anchor the US military presence in the region. Members promote this objective in various ways: (a) by advising policymakers, either in direct communication or through the policy recommendations in their research outputs; (b) by attempting to influence the general public and other relevant audiences through the mass media and social media; and, in some cases, (c) by making policy themselves. Table 1 summarises the analytical criteria for TAPEC membership. The four criteria are distinct and only individuals who meet all of them can be members. Not all experts on East Asian security are therefore members. Nor are all the experts who accept the validity of the stability belief, unless they also take part in the community’s policy project.

Table 1 Analytical criteria for TAPEC membership.

TAPEC members are connected by their authoritative role as experts on the same topic, their shared causal and normative beliefs, and their common policy enterprise. But TAPEC is also a ‘community’, in the sense that interactions between members constitute a network of crisscrossing interpersonal ties, although not every member has direct contact with all the others. More or less institutionalised social settings provide TAPEC with arenas to share and develop ideas and present them to decision-makers. This includes universities and academic conferences; think tanks; fellowship and young leaders programmes; academic and policy-related publications and social media; and many of the hundreds of Track II initiatives going on in East Asia and across the Pacific. Many of these sites are organised around objectives or practices that embrace or support TAPEC’s policy project, examples of which are shown in Table 2. However, TAPEC members are also active in organised settings whose key missions do not necessarily include anchoring the US military in the region, such as the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP) and ASEAN Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ASEAN-ISIS). Few transnational settings of international security expertise in the Asia-Pacific region are built on principles that openly contradict the tenets of TAPEC.

Table 2 Examples of institutions in TAPEC’s epistemic infrastructure.

TAPEC members’ shared support for US leadership is not ultimately dependent on a normative commitment to the US state, but instead stems from the view that the US military presence is a necessary factor in regional stability. Hence, not all TAPEC members are necessarily ‘pro-US’. Nor are they all ‘anti-China’; many reject containment policies and advocate encouraging China to take a full part in the international community. For example, Yoon Young-kwan, Professor of International Relations at Seoul National University and former Foreign Minister of South Korea (2003–4), advocates reduced US arms sales to Taiwan as part of a grand bargain between the US and China in East Asia, but still favours to maintain the regional military status quo, including US security guarantees to Taiwan.Footnote 74 In general, there is a great deal of variety, complexity, and nuance in many individual TAPEC members’ thinking on international affairs, and far from everything they do professionally is related to their belonging to TAPEC. Some of them might even belong to epicoms concerned with other issues as well, such as the ‘ASEAN-ologists’ described by David Martin Jones and Michael Smith.Footnote 75 This therefore implies that there is much intellectual and political contestation going on within TAPEC – except, of course, when it comes to its core beliefs and policy enterprise. In short, the TAPEC concept is not meant to capture everything meaningful about the social and political relevance of its members’ professional activities, just some parts of critical importance to the US-led security hierarchy in East Asia.

TAPEC exists in a field defined by the struggle for what counts as common-sense knowledge about East Asian international security. The field is transnational since the most powerful representations tend to emerge more or less concurrently across different linguistic and political entities. Moreover, a relatively non-discriminatory relation between academic knowledge and other types of expert knowledge characterises the field. This reflects IR – which arguably has the highest concentration of knowledge capital in the field – more broadly. IR stands out among the social sciences by tracing its ideational origins not to universities, but to the world of practitioners.Footnote 76 The blurring in the discipline between theory (IR) and practice (ir) often triggers a ‘confusion of observational theories and foreign policy strategies’.Footnote 77 This too helps to explain the strength of the stability belief; the analytical ambiguities probably increase its political appeal, since they open the way for nearly limitless evidence of US-produced ‘stability’.

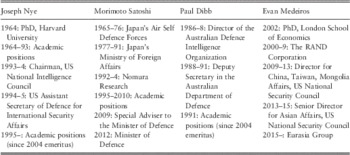

Since TAPEC is a dominant actor in the field, we should expect mechanisms of persuasion and social influence to favour novice experts on East Asian security to conform to the epicom’s belief and norm systems. On joining TAPEC, an extensive infrastructure of expertise opens up opportunities for employment, funding, and social recognition. In this way, to paraphrase Benjamin Disraeli, ‘The Asia-Pacific is a career.’ Table 3 presents a non-exhaustive list of current TAPEC members – the actual membership is much bigger – divided by primary profession and geographical base.Footnote 78 The examples have been picked inductively with the objective to illustrate the breadth of TAPEC’s membership. I have included several of the most influential members as well as some junior ones. The emphasis on US individuals reflects the American impact in the field of knowledge production on East Asian international security.

Table 3 Non-exhaustive list of TAPEC members.

As Table 3 indicates, TAPEC members are well represented in many of the field’s national and disciplinary dimensions. This is a key advantage, since the existence of an abundance of actors with the ability to traverse subfield boundaries increases TAPEC’s potential impact. Many members would fit into two or more of the occupational categories in Table 3. TAPEC’s multidisciplinary nature is thus also present within its individual members. What I call ‘scholar-officials’ are at the core of TAPEC.Footnote 79 These are security experts engaged in three activities: (a) academic research on international affairs; (b) governmental foreign and security policy work; and (c) the public policy debate in their field of expertise (see Table 4 for examples of the career paths for scholar-officials). Scholar-officials have direct influence over policymaking in their role as government officials, but also wield indirect influence through their participation in public and expert debates. Their knowledge authority is generally not questioned, but instead bolstered by their dual role as academics and practitioners, thanks to the intimate connection between practical knowledge and scholarship in the field. All other things being equal, scholar-officials have a more influential role than TAPEC members with a presence in only one or two subfields.Footnote 80

Table 4 Examples of TAPEC scholar-officials’ career paths.

The field in which TAPEC is active is structured around the struggle to define what counts as common-sense knowledge on East Asian international security. Many of the debates in the field do not directly concern the US regional role.Footnote 81 When this role becomes a topic of contestation, however, TAPEC emerges as an actor. These disagreements also include competing collective actors.

The field contains at least one other fully-fledged transnational epicom of security experts with a credo that clashes with the stability belief, here identified as the ‘Anti-Hegemonic Epistemic Community’ (AHEC). AHEC members share a causal knowledge claim that the US military presence in East Asia disrupts the ability to establish more enduring peaceful relations between regional actors; a set of social scientific notions to validate this claim; a principled belief that the US should withdraw, significantly decrease, or at least not enhance its force presence; and a policy enterprise to convince the public and policymakers of this objective. Prominent members include the historian, John Dower, the political scientists, Gavan McCormack and Karel van Wolferen, the former Japanese diplomat, Magosaki Ukeru, and, until his death in March 2015, the former Prime Minister of Australia, Malcolm Fraser. Although these ideas have certain traction among strands of East Asian public opinion,Footnote 82 AHEC’s influence on the expert discourse on international security is fairly circumscribed. The causal knowledge claim is not thoroughly institutionalised in any regional foreign policy bureaucracy, with the possible exception of North Korea – and that is probably completely unrelated to AHEC’s possible influence. Chinese government representatives have a mixed record of professing its support for the US military presence in East Asia,Footnote 83 on the one hand, and pointing out the negative consequences of its presence,Footnote 84 on the other.

Leaving aside the question of the possible analytical weaknesses in the knowledge claim, we can identify two factors that limit the success of AHEC. First, although AHEC has established a sphere of discussion built around journals such as Critical Asian Studies and Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, this has not developed into a transnational infrastructure of expertise, complete with think tank networks, regular conferences, fellowships, young leaders’ programmes, and so on. This limits the opportunities for policymakers to come into contact with AHEC’s ideas and, if they do, to perceive them as authoritative. It also makes it difficult to make a career within AHEC, which probably reduces its supply of talented and ambitious experts. Second, AHEC members tend to combine the above claims with additional normative criticism of subordinate states’ decisions to relinquish policy authority to the US.Footnote 85 In this sense, AHEC is a mixture of an epicom and an ‘advocacy network’.Footnote 86 This normative critique, however, has been largely ineffectual against the knowledge claim that US hierarchy is necessary to secure systemic stability. Confident in the validity of the stability belief, two TAPEC members, for example, have dismissed Australian anti-base campaigners as, ‘highly ideological, pathologically anti-American’.Footnote 87

The field also encompasses a number of more local knowledge actors with claims and practices that tend to conflict with TAPEC. One prominent example is conceptualised here as the ‘Peaceful Rise Epistemic Community’ (PREC). With a membership that encompasses large parts of the Chinese security intelligentsia, as well as some foreign experts, PREC members share the causal belief that China’s foreign policy is inherently peaceful; the normative belief that worrying about the effects of growing Chinese capabilities is irrational and based on the malicious or ignorant ‘China threat theory’, or on out-dated ‘Cold War thinking’; and a policy enterprise to prevent foreign containment of China’s rise to undisputed great power status. PREC’s core beliefs are ultimately validated by a cultural exceptionalism that identifies China as a new type of benevolent great power,Footnote 88 and by the allegedly infallible scientific analytical methodology of the Chinese Communist Party’s political theory.Footnote 89 These notions do not contradict US military supremacy per se, and the majority of Chinese IR scholars arguably adhere to the stability belief.Footnote 90 PREC members, nonetheless, regularly dispute TAPEC members’ common claim that US forces are necessary to deter Chinese expansionism. Language hurdles, dissimilarities in academic culture and a general failure to provide convincing analytical backing for China’s inherent peacefulness are all likely to help explain PREC’s limited success in influencing international debates. It is also important to point out that not all Chinese security experts are PREC members. For example, Yan Xuetong, one of China’s leading IR scholars, implicitly dismisses the validity of PREC’s causal knowledge claim by arguing, among other things, that ‘there will be few win-win situations in China’s ascent to a superpower’.Footnote 91

TAPEC and Japan’s strategic vacillation, 2009–10

The following episode illustrates how TAPEC has taken on a key role in reproducing the stability belief as an authoritative knowledge claim, and how this influences subordinates in East Asia to adopt a positive view of US security hierarchy relative to alternative security arrangements. The section thus provides further elaboration of the arguments presented earlier in the text. However, it should be pointed out that this is not a structured and focused case study that beyond doubt substantiates the causal significance of TAPEC. I shall return to the issue of limitations and further research in the concluding section.

The Obama Administration initially faced a serious problem with its East Asia policy. In the early autumn of 2009, the newly elected Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government, led by Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio, declared its intention to implement several important changes in Japan’s foreign and security policy. Three such changes deserve special attention: (a) making the Japan-US relationship more equal, while at the same time striking a more even balance between Japan’s relationships with the US and China; (b) working towards establishing an East Asian community built on functional integration, seemingly without US participation; and (c) revoking a previously concluded agreement with the US in order to move the contentious Futenma Marine Corps base out of Okinawa prefecture, and possibly out of Japan altogether.Footnote 92 If successfully executed, these changes could have decreased the US force presence in Japan and opened the way for Tokyo to enter into alliance-style relationships independently of Washington. It could also have served to spur other countries in the region to reconsider their dependence on the US military. In other words, Japan – arguably the key US regional ally – was planning a strategic reorientation that might have reduced the level of US security hierarchy in East Asia.

From the outset, the Japanese government’s new strategy was heavily criticised by different camps both inside and outside Japan.Footnote 93 Much of this criticism drew on the authority of the stability belief: the DPJ government was accused of not appreciating that any cutbacks in the US military presence would jeopardise the security situation in Japan and the region. Resistance from the US government, conservative Japanese news media and the DPJ’s main political rival, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), was to be expected. Slightly more surprising, perhaps, was the consistent behind-the-scenes opposition from high-ranking officials within Japan’s own foreign ministry. Thanks to the massive leak of US diplomatic cables by the WikiLeaks organisation in 2010, we have insights into the diplomats’ resistance to all three of the policy changes outlined above, or at least interpretations of their statements of resistance by the US diplomats who wrote the cables.

Saiki Akitaka, Director General for Asian and Oceanic Affairs, confessed to Kurt Campbell, the US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, on 17 September 2009 that he could not understand the Hatoyama Administration’s call for a more equal relationship since the Japanese-US relationship was ‘already equal’.Footnote 94 In another meeting with Campbell on 12 October, Saiki stressed that Hatoyama’s comments that Japan had been excessively dependent on the US were ‘inappropriate’ and had ‘surprised’ the ministry. Saiki also acknowledged that his boss, Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya, had been ‘obstinate’ about not including the US in the blueprint for an East Asian community. As a ‘MOFA bureaucrat’, however, Saiki expressed his view that ‘it was unthinkable to exclude the United States’.Footnote 95 On 12 November, Japan’s Ambassador to the US, Fujisaki Ichirō, offered friendly advice to his US counterpart on how President Obama could put pressure on Hatoyama in their meeting the next day: ‘the President should tactfully make the point that an expeditious resolution of the Futenma Replacement Facility … issue is a problem for Prime Minister Hatoyama and Japan to resolve (not the United States)’.Footnote 96

Why did senior Japanese diplomats undermine their elected leaders? Self-interest is likely to have played a role – the DPJ had promised voters that it would wrestle decision-making power from the hands of bureaucrats to elected politicians.Footnote 97 Nonetheless, a strong conviction in the truth of the stability belief and apprehension that the DPJ government did not appreciate its importance were also factors in the stance taken by ministry officials. When it came to ‘the details and rationale behind US-Japan security policy’, Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs Yabunaka Mitoji told US Ambassador John Roos on 21 December, ‘some DPJ leaders’ faced a ‘sometimes steep learning curve’. According to Yabunaka, it was therefore advisable to push for informal talks instead of a formal bilateral dialogue in order to avoid ‘the Hatoyama Administration and/or ruling coalition political leaders [taking] positions based on incomplete or erroneous understandings of alliance issues and options’. At the same time, Yabunaka expressed some confidence about ‘efforts to educate’ those ‘television commentators and politicians’ who lacked a ‘strong a grasp of security issues’.Footnote 98 Saiki, too, in his September talks with Campbell, called the Hatoyama Administration’s strategy of challenging the US ‘stupid’, but noted that ‘they will learn’.Footnote 99

These Japanese diplomats are all TAPEC members; both Fujisaki and Yabunaka have taken up academic and think tank positions since their retirement. Influential US TAPEC scholar-officials, such as Richard Armitage, Victor Cha, Michael Green, and Joseph Nye, were also active early on in relying on the axiomatic knowledge authority of the stability claim to discredit the DPJ government’s strategic reorientation.Footnote 100 Frequent contacts between TAPEC members in different subfields continued throughout the tumultuous period. In January 2010, for example, the Japanese Embassy helped to sponsor the Sixteenth Japan-US Security Seminar in Washington, DC. This biannual conference is one of the more high-profile regular gatherings between Japanese and US ‘alliance managers’ – a tight community of bureaucrats, politicians, think tankers, and scholar-officials, the vast majority of whom belong to TAPEC. In a written rundown of one of the closed sessions, Brad Glosserman set out the mainstream sentiment among TAPEC members at the time:

Many see the frictions in the Japan-US alliance as stemming from the failure of the new Japanese government to appreciate the complexities of issues in the security arena; as it becomes more informed of those nuances, foreign and security policies will revert to the norm of its Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) predecessors.Footnote 101

The need to educate misinformed politicians about the validity of the stability belief was a reoccurring theme at the conference, as can be seen in Glosserman’s summary of Shelia Smith’s presentation:

A country that lacks a tradition of alternation of governments is unlikely to have an informed opposition. There should be outreach to a wider group of individuals. Information needs to [be] better distributed. There needs to be a better understanding of the role the alliance plays in securing Japan and the role of the Marines in accomplishing that objective. Japan’s opposition – whoever it is – needs to learn to think in terms of the national interest[.]Footnote 102

Such activities enjoyed significant success in shaping perceptions of the Japanese Administration’s strategic shift, just as expected by many TAPEC members. This helped to make Hatoyama’s position increasingly untenable. On 4 May 2010, less than eight months after the DPJ assumed power, Hatoyama told reporters that at the time of the election of 2009, which brought his party to power, ‘I did not think that the Marine Corps was necessarily needed in Okinawa as a deterrent.’ However, ‘the more he studied’ he eventually came to ‘realize’ that their presence served deterrence purposes.Footnote 103 That is to say, Hatoyama did an about-face and – in the words of the TAPEC members referred to above – declared that he had been ‘educated’ about the validity of the stability belief. Hatoyama resigned as prime minister less than one month later. This public acknowledgement of the stability belief signified Japan’s decision to abandon its proposed strategic reorientation and instead throw its full support behind a regional security order based around a bolstered US hierarchy.

The Japanese government lacked fixed preferences about which international security order was best able to meet its professed interests. Instead, it vacillated between two different orders. It eventually endorsed the order championed by the US, thus enforcing US security hierarchy, but this could not have been predicted based only on the analyst’s assessment of the objective security-endowing qualities of these orders. The episode highlights how entrenched knowledge structures in bureaucracies can contribute to path dependency in policymaking. At the same time, it also shows that active reinforcement is necessary to keep these structures in place. The stability belief was dominant in Japan in 2009, but it was not dogma. The process that led to the downfall of the Hatoyama Administration was also a struggle over what counts as valid knowledge on international security. The Hatoyama Administration has frequently been accused of incompetency in its conduct of foreign policy. While I do not dispute that its executive skills were far from optimal, my point is that allegations of ineptitude at least partly stems from the Administration’s initial refusal fully to accept the alleged wisdom of the stability belief.

Summary and discussion

Policymakers partly agree to have their states take on subordinate positions in hierarchical relationships due to their cost-benefit calculations.Footnote 104 But on what knowledge of costs and benefits are these calculations based? This article suggests epicoms as a general explanation of how this knowledge is produced. In this way, it highlights the crucial role of expertise in the emergence and sustainability of hierarchies in world politics.Footnote 105 I thus follow up on calls to identify the different sources of dominant states’ legitimacy in hierarchical relationships;Footnote 106 the agents and networks behind the ideational structures underpinning global governance;Footnote 107 as well as the linkages between the different hierarchical logics of functional bargains, on the one hand, and knowledge structures, on the other.Footnote 108

By analysing the generation and political mobilisation of security knowledge, the study sheds light on a crucial but so far neglected aspect of the remarkably persistent US security hierarchy in East Asia. I have attempted to demonstrate that the stability belief – the ubiquitous idea that US military predominance ensures regional stability – is critical in convincing East Asian policy elites that the US-led order is legitimate. Since the analytical merit of this belief does not live up to what one would expect from its close to universal traction, I have moreover argued that we must study the knowledge politics behind the ongoing constitution of the belief. A transnational and multidisciplinary network of experts on international security – TAPEC – is found to be primarily responsible for reproducing the belief as an authoritative knowledge claim. TAPEC therefore makes US security hierarchy in East Asia possible. It can be understood as a key source of US ‘soft power’.Footnote 109 TAPEC helps to make US hierarchy attractive in the eyes of East Asian policymakers.

Through TAPEC, the legitimacy of US hierarchy in East Asia to a certain extent relies on a transnational community decoupled from absolute state control.Footnote 110 This might seem like a precarious foundation for international leadership. It is however doubtful whether the US would be able to rely solely on military might, economic prowess or, for that matter, cultural attractiveness or values-based transnational collective identities to secure its dominant military presence in East Asia. TAPEC might therefore be a necessary condition for the continuation of US security hierarchy. The politics of expertise thus becomes an essential indicator when theorising about the possibilities of a ‘power shift’ in East Asia. The burgeoning literature on the topic, however, has so far more or less completely overlooked the mechanisms by which knowledge on international security is created and politically employed.Footnote 111

Such neglect might contribute to a tendency to underestimate the resilience of US hierarchy and, conversely, to overestimate China’s ability to translate economic and military capabilities into real policy effects and the creation of a sphere of influence at the expense of the US. David Shambaugh, for example, predicted about a decade ago that, ‘The nascent tendency of some Asian states to bandwagon with Beijing is likely to become more manifest over time’;Footnote 112 and Yan Xuetong agreed that: ‘China’s endeavours in East Asian regionalization will effectively enhance its ability for political mobilization over the next 10 years.’Footnote 113 A few years later, Mark Beeson wrote in a similar vein, ‘… China has begun to enunciate an alternative vision of development and international order that may help to consolidate its position at the centre of an emergent regional system at the expense of the US’.Footnote 114 We have instead seen the opposite. Identifiable Chinese influence in many issue areas remains limited or has declined,Footnote 115 while the US-led security hierarchy, as seen in the regional embrace of the US policy to ‘pivot’ to Asia, has grown stronger.

Measuring economic and military capabilities is clearly not enough in order to understand this turn of events. Attention on the social production of legitimacy enables more accurate explanations and predictions of the dynamics of international hierarchies. While this productively has been done in the East Asian context,Footnote 116 the important role of expert knowledge has so far been left largely untouched. I do not claim that TAPEC is the sole reason why East Asian elites perceive the US security hierarchy as legitimate. While I hypothesise that security expertise becomes more important when – as in East Asia – interstate identification is thinner and military conflict is rarer, more comparative research is needed on expertise relative to other sources of international authority. Moreover, the TAPEC case requires further inquiry in order to determine more exactly the causal mechanisms and scale of its impact. This study has concentrated on conceptualising the community and the field in which it is active, as well as criticising rival explanations for the strength of the stability belief. Future research should compare TAPEC’s influence in different national contexts in East Asia, and look into contrasts with other regions with variance in the presence of extensive transnational epicoms. Process tracing, ethnography, and structured and focused case studies are also needed to elaborate the mechanisms of TAPEC’s influence. Studies of the origins of TAPEC, as well as its role in critical junctures, such as after the end of the Cold War, would also be valuable.

To conclude, since IR scholars often take part in creating the very phenomena they are studying, a reflexive attitude towards this connection is imperative.Footnote 117 While the epicom concept was originally developed by IR scholars to study natural scientists, this study turns the concept around by directing the searchlight at an epicom in which IR scholars themselves play prominent roles. Some in the IR profession have called on their peers to do more policy relevant theoretical work,Footnote 118 to disseminate their ideas to policymakers,Footnote 119 and to take on government positions.Footnote 120 Since the scholarly members of TAPEC embrace such advice to a greater extent than their colleagues in many other subfields of IR, the article can be read as a case study of the opportunities and pitfalls, for scholarship as well as for policy, of proactive academic involvement in the wider policymaking process.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments on earlier (in some cases, much earlier) versions of this article, the author would like to thank the editors and reviewers of Review of International Studies, Hans Agné, Idris Ahmedi, Andrew Bennett, Henrik Berglund, Stefan Borg, Niklas Bremberg, Steve Chan, Félix Grenier, Karl Gustafsson, Stefano Guzzini, Linus Hagström, Jan Hallenberg, Ulv Hanssen, Joakim Kreutz, Niklas Nilsson, Tarek Oraby, Gustav Ramström, J. Patrick Rhamey, Thomas Risse, Jeff Roquen, Jonas Tallberg, Jan Teorell, and Stein Tønnesson.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210516000437