Introduction

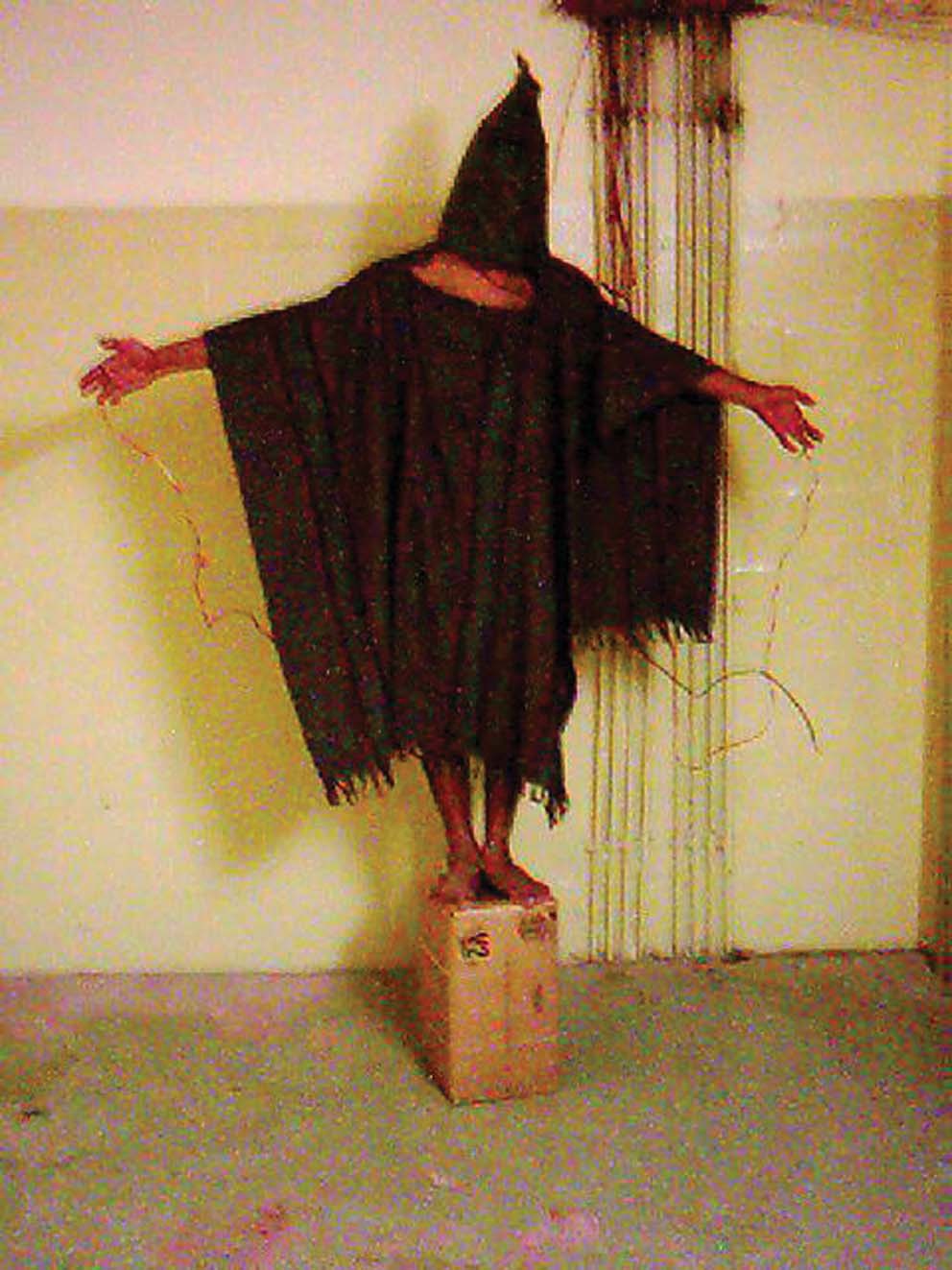

It is now a decade since the photos from the prison in Abu Ghraib were shown, first to an American audience watching Sixty Minutes II on 28 April 2004, then almost instantaneously reaching anyone with a television or internet connection. The photographs documented abuse that the US media had already been informed was under investigation, but which in the absence of images had generated little coverage.Footnote 1 The sense of horror and disbelief within America was immediate and widespread and in spite of President George W. Bush's attempt to explain that ‘This is not America’,Footnote 2 the photos ‘have become symbols in the Arab world of American imperialism’.Footnote 3 As one military official put it, this was a ‘moral Chernobyl’.Footnote 4 Chock and outrage was generated by the brutality of the abuse, the vast number of photos, and the multiple forms of violence depicted.Footnote 5 Yet, as often happens when multiple images represent the same event, some quickly gained a heightened circulation: the female guard Lynndie England with a collapsed prisoner on a leash, pyramids of naked prisoners with smiling guards posing behind them, prisoners facing barking dogs, and scenes of forced masturbation. As ‘Abu Ghraib’ became part of what Cornelia Brink calls collective visual memory, one photo stood out as ‘the most emblematic’: the one showing a hooded prisoner on a cardboard box, clad in a poncho-like blanket, arms outstretched and wires attached, who was told that electrocution would appear were his arms to fall down.Footnote 6 The image, now known as ‘The Hooded Man’, was on the cover of the 8 May issue of The Economist beneath the headline ‘Resign, Rumsfeld’, the opening photo of Seymour Hersh's much quoted essay on 10 May in The New Yorker and in many other media reports.Footnote 7 Over the coming months and years, the hooded prisoner – and other photos from Abu Ghraib – moved from the news media to museum spaces, exhibition catalogues, and academic publications.Footnote 8 ‘The Hooded Man’'s rise to iconic status has been produced not just by its frequent reproduction, but by the numerous ways in which it has been appropriated by image makers across a variety of genre, media, and locations. It has been the template for magazine covers and editorial cartoons, on murals, public posters, sculpture, recreated in Lego, and inserted into paintings and montages.Footnote 9

Assessing the political impact of ‘Abu Ghraib’ in general and the hooded prisoner in particular is not easy. Those sceptical of its effect argue that US mainstream news media largely followed the Bush Administration's framing of Abu Ghraib as ‘abuse’, not ‘torture’,Footnote 10 that the photos did not prevent George W. Bush's re-election in 2004, that prosecution and convictions have been few and targeted lower level personnel,Footnote 11 and that the wider American use of detention and confinement in the War on Terror continued.Footnote 12 Yet, while no direct, immediate causal impact on American policy can be established, the hooded prisoner and the violations he embodies continue to resurface in critiques of America's role in the world, at home and abroad. In 2009, one example of American leaders continuing to take ‘Abu Ghraib’ seriously was evidenced by President Barack Obama's blocking of the release of up to 2,000 new photographs of alleged prisoner abuse on the grounds that they would ‘inflame anti-American public opinion and [to] put our troops in greater danger’.Footnote 13

‘The Hooded Man’ is far from the only example of an iconic image's ability to represent key events in international politics. A Western-centric list from World War II onwards includes the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima (1945), the shooting of a suspected Vietcong in Saigon during the Tet Offensive (1968), the naked girl fleeing the napalm bombing in Vietnam (1972), the Bosnian prisoners behind barbed wire (1992), the falling World Trade Center Towers on 11 September (2001), the toppling of Saddam Hussein's statue (2003), the charred, lynched contractors from Fallujah (2004), and the dying Iranian activist Neda Agha Soltan (2009).Footnote 14 As the last example indicates, icons can originate from civilians present at the scene with nothing but cell phones. The Muhammad Cartoon Crisis of 2006 shows that iconic – and highly contested – images can come from a variety of genres, including nondocumentary ones like cartooning. Iconic images do more than transmit ‘what happens’. They condense and constitute the meaning of major events like World War II, Vietnam, and the War on Terror. They are, as David D. Perlmutter puts it, believed to ‘say it all’, not least as time moves on and ‘lessons’ crystallise.Footnote 15 To make an analogy to discourse analysis, icons can be seen in Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe's term as ‘visual nodal points’: privileged discursive/visual signs that provide a partial fixation to structures of meaning.Footnote 16 Yet as the nodal point relies on linking and differentiation to other signs for meaning to be generated, the icon does not ‘speak’ foreign policy on its own. It is drawn upon by discursive agents to constitute events, threats, subjects, and identities, to defend policies taken or promote alternatives not pursued. Icons are on the one hand presented as if they have a self-evident foreign policy message, yet on the other hand, we frequently find competing constructions of what that ‘self-evident’ message is.

Over the past fifteen years, scholars from the fields of Political Communication, Sociology, Art History, English Language and Literature, and Visual Culture have produced a substantial body of work on how to define and analyse the icon.Footnote 17 Yet icons have not been explicitly theorised within International Relations (IR) nor have they been subjected to empirical studies.Footnote 18 This article seeks to fill this gap. The starting point is that while many scholars within IR might be sympathetic to the argument that iconic images are important to world politics there is not a clear understanding of what that ‘importance’ is or how to study it. The goal of the article is thus two-fold: to provide a set of concepts and distinctions that allow us to identify a phenomenon – international icons – and to develop a theoretical framework through which one can analyse the ways in which icons impact world politics.

These goals place the article as a contribution to current research within the field of IR on images and international politics. Scholars like David Campbell and Michael C. Williams called a decade ago for IR to meet ‘the pictorial challenges’ and acknowledge the specificity of the ‘communicative acts’ that images perform, and a substantial body of work has risen to the occasion.Footnote 19 A distinctive concern in parts of that work has been whether a critical potential can be attributed to – or drawn from – images. Cynthia Weber, for example, has shown how in some cases ‘contemporary popular visual language might more successfully evacuate political responsibility from politics than textual language now can’, while other studies have focused on images that may identify resistance in ‘previously unacknowledged political spaces’ and conjure different ways of being critical than those familiar from spoken or written texts.Footnote 20 Starting from securitisation theory, Frank Möller and Juha Vuori have discussed the conditions under which images may desecuritise, that is, facilitate a move out of the logic of urgency, threats, and radical measures that characterise the securitised.Footnote 21 Roland Bleiker and Amy Kay (2007) have identified ‘dialogical images’ that challenge ‘the iconic images of humanist [HIV/AIDS] photography, where the flow of information is controlled, hierarchical, and works in only one direction’.Footnote 22 Klaus Dodds holds that the editorial cartoons by Steve Bell for The Guardian ‘subvert the contemporary geopolitical condition’.Footnote 23 This concern with the critical potential of images provides a clear point of convergence with studies from the fields of Political Communication, Art History, and Visual Studies that trace how icons become appropriated. However, as I will argue below the question of what a critical appropriation is, is complicated.

This article is aimed at an IR audience and as such one of its goals is to introduce existing work from outside of IR. That raises the question whether a specific IR approach to icons is warranted, or whether the reader may find the same arguments elsewhere? The answer, in short, is no. While providing an extremely valuable set of writings, works from Visual Studies, Communication, Art History, etc. have not theorised the international dimensions of iconic images. These international dimensions fall in three parts. First, some icons gain recognition and generate responses across state borders and this in turn open up the question of effect beyond that of domestic electoral politics which has been the traditional domain of Political Communication. Second, to theorise the icon as international is not only to conduct comparative studies of how domestic media in different countries cover foreign policy events – another stable of Political Communication research – but to ask how ‘the international’ itself becomes constituted as a particular space separate from ‘the national’. Third, it is to theorise icons as inherently contested and always invoking national and international ‘wes’ [plural] which are fractured and thus not identical to a homogenous national citizenry or international community.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section provides a discussion of how to define the icon, an account of the emotive qualities of icons, and a conceptualisation of the international icon. The second section turns to a discussion of how icons can be said to have a political impact drawing in works on the CNN-effect, news coverage, and the contemporary media environment. The third section theorises the relationship between an icon and the images that are generated through its appropriation and presents a three tiered analytical strategy for studying the impact of the international icon on world politics. The fourth section applies the theoretical framework developed in the first three sections in a case study of ‘The Hooded Man’ photo from Abu Ghraib. The fifth and concluding section reflects on the wider potential for research on iconic images in IR.

Introducing the international icon

Defining the icon

The word ‘icon’ is used colloquially to refer to humans who achieve celebrity status, to logos such as Apple's trademark, to symbols like the swastika, as well as to easily recognisable and widely disseminated images, mostly photographs that ‘made history’.Footnote 24 This article follows the majority of the academic literature in Visual Culture, Communication, and Art History and defines icons according to the last usage.Footnote 25 This definition is arguably more narrow than the colloquial and some might find it too narrow on the grounds that some symbols are highly political (take the use of swastika in recent Greek protests against the financial conditions required by the EU), that logos can be appropriated in critical ways (MacDonald's Golden Arches), that ‘iconic humans’ might be drawn from the field of politics (Nelson Mandela) or that their celebrity status is used to campaign for political causes (Bono's role in the RED campaign to bring drugs to HIV/AIDS patients in Africa). Yet, this article is focused on freestanding, recognisable images on the grounds that they constitute a sufficiently distinct phenomenon with particular dynamics and implications for domestic and international politics, dynamics and implications that set them apart from logos, symbols, and iconic humans and celebrities. The article proceeds from Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites' definition of the icon (slightly modified) as ‘those [photographic] images appearing in print, electronic, or digital media that are widely recognized and remembered, are understood to be representations of historically significant events, activate strong emotional identification or response, and are reproduced across a range of media, genres, or topics’.Footnote 26

As might be noticeable from the modification to Hariman and Lucaites' definition, they, like most existing studies, focus on photographic icons. Within the media of photography, photojournalism might be the genre from which most icons are drawn. The photos from Abu Ghraib are not photojournalistic however, but amateur photography not intended for a broader public use; the video from which the iconic still photograph of the dying Neda is drawn is now referred to as citizen journalism.Footnote 27 Moving further away from photography's claim to record events factually there are images from other genres that satisfy the general part of Hariman and Lucaites' definition as images from the genres of drawing, painting, and printmaking have achieved iconic status. The genre of political cartooning has a history of producing domestic and international crisis of which the Muhammad Cartoon Crisis of 2005–6 is a recent example.Footnote 28 Political posters have a tradition of seeking to rally a population around an ideological, patriotic, or revolutionary cause, usually incorporating imagery and slogans. J. M. Flagg's 1917 ‘I want you for U. S. Army’ is a classical case in point; more recently Shepard Fairey's ‘Hope’ poster of Barack Obama has been lauded as ‘iconic’ of the 2008 presidential election and has provided the template for commemoration of ‘Neda’ in 2009, for Occupy Wall Street with a Guy Fawkes replacing Obama, and in support for Edward Snowden.Footnote 29 The concealment of Picasso's Guernica at the entrance to the UN Security Council as Sectary of State Colin Powell and American UN Ambassador John Negroponte presented ‘evidence’ of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction in February 2003 and the subsequent adoption of the painting in antiwar protests illustrate that artworks can achieve iconic status, too.Footnote 30 As our definition of icons should be open to images from any visual genre, we should simultaneously acknowledge that those vary in terms of their epistemic conventions and the way in which audiences are expected to respond.

A final definitional distinction is between the discrete and the generic icon. The former refers to ‘a single image with a definitive set of elements – the famous photo or footage [or other image]’, the latter to when ‘certain elements are repeated over and over, from image to image, so that despite varying subjects, times, and locations, the basic scene becomes a familiar staple, a visual cliché’.Footnote 31 Discrete icons may actually consist of several images as in the case of ‘Tiananmen Square’ where three images circulate but ‘nobody seems to care enough about the differences to comment on them’.Footnote 32 This article is primarily concerned with the discrete icon on the grounds that there are specific dynamics surrounding it: it has a distinctiveness and an identity, a specific story about its gestation and circulation, and a ‘nodal point’ character. Yet, the category of generic icons is important, first, because there are cases of images that comply with our general definition even if one particular image cannot be picked out as ‘the’ iconic one. Lynching photographs from the American South for example arguably had and have such a status. Paintings of the Virgin Mother and Child in Western art are another example.Footnote 33 Second, the concept of the generic icon is methodologically useful for identifying and understanding the iconic status of discrete icons because the latter may gain some of their visual power from referring to previous icons and these are often of a generic kind.Footnote 34 Mette Mortensen describes this as an ‘icon's iconicity’,Footnote 35 or we might use Julia Kristeva's theory of intertextuality to coin the concept of inter-iconicity. Inter-iconicity refers to the way in which an icon supports its claim to iconic status through referencing older icons. Importantly, through this process of ‘icon quoting’, the iconic status of the older image is also reproduced. One might for example read the image of charred contractors hanging from the bridge of Fallujah in 2004 as invoking the photos of dead American soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu in 1993, an inter-iconicity supported by media coverage such as San Francisco Chronicle's front page story on 1 April 2004: ‘Horror at Fallujah: In U.S., echoes of Mogadishu’. Finally, generic icons might be closer to the original Christian understanding of the icon where no specific image was ‘the’ icon, icons were rather a special category of divine images, an understanding to which we now turn.

Religious and photographic icons

An exploration of the iconic image might usefully begin with the word's etymological roots, the Greek eikon ‘simply means picture, image in the broadest sense’.Footnote 36 From the ancient Greek world, the word travelled to the early Christians and the Eastern Orthodox Church where icons were cult images ‘which according to legend were not created by human hands, [and] were regarded as authentic copies of the “original images” of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints or biblical scenes’.Footnote 37 Crucially, argues Cornelia Brink, ‘There seemed to be a direct causal relationship between the copy and the original image’, such that through the icon the ‘invisible divine’ could be imagined by the believing spectator.Footnote 38

As noted above, most contemporary academic work theorise iconic images as photographs. The photograph obviously provides a different kind of documentation than the Orthodox icon, namely one based on the exact reproduction of events in the physical world, yet what unites the two kinds of icons is that both are believed to be authentic copies of what took place or existed.Footnote 39 Where the religious icon provides a conduit to the realm of the divine, the photograph recreates the space and moment of its capture, that is, in Judith Butler's words ‘a kind of promise that the event will continue’.Footnote 40 Both forms of icons thus stand in an emotionally charged relation with its spectator or devotee. The emotional quality bestowed upon icons is stressed in Hariman and Lucaites' definition listed above. It is also brought out by visual theorist Hans Belting who describes how we might look at images ‘as if we were exchanging glances with living humans’, although of course images ‘cannot “glance” by themselves’.Footnote 41 Adopting the distinction between depth and surface, Jeffrey C. Alexander suggests that icons uses the latter to draw us deeper, ‘the icon points outside of itself, and outside of the subject, to something else, something in the world’.Footnote 42 These theorisations of the icon's emotive, captive qualities effectively define the icon according to its impact on the viewer. Importantly, the capacity to evoke ‘iconic emotionality’ cannot be derived exclusively from the image itself. First, images might be aesthetically beautiful and striking, yet not become icons. Nor are aesthetic qualities necessarily crucial as the example of Kurt Westergaard's sketch of Muhammad with a bomb in his turban – the icon of the Danish Cartoon Crisis – shows. Second, some depictions of suffering and agony become iconic, most others do not. Third, formal compositional traditions and aesthetic conventions identify socially embedded and thus powerful expectations about the form of knowledge produced through an image and about the expected audience response.Footnote 43 Thus formal characteristics of a photographic image can in some cases provide a partial explanation why a particular image achieves iconic status when several images of the same event compete for iconic candidacy.Footnote 44 Perlmutter holds more specifically that ‘One formal element that most icons seem to share, however, is their spareness’, yet some icons, like ‘Napalm Girl’ involve quite a complex composition.Footnote 45 To say that no image is destined to become iconic solely by virtue of its composition or the significance of the event(s) it depicts is to argue that there have to be agents – editors, journalists, politicians, commentators – who constitute the image as having iconic power. According to Perlmutter this typically happens immediately upon publication, yet as the Cartoon Crisis shows, it might also take months of discursive construction to generate and convince an audience that an image has an exceptional status.Footnote 46

Another similarity between religious and photographic icons is that both achieve a symbolic status, that is, they ‘claim to condense complex phenomena and represent history in exemplary form’.Footnote 47 Wars, for example, become memorialised through a set of iconic photographs that symbolise a much larger body of carnage, destruction, and glory;Footnote 48 the Virgin Mary embodies a religious universe. Icons thus become like visual nodal points, that is key signs within discourses that construct say ‘Iwo Jima’ as emblematic of American patriotism, virtue, sacrifice, and solidarity. Hariman and Lucaites argue that iconic images are salient for public, political life as their status is deeply connected to – if not caused by – an ability to act as ‘symbolic resources for both social cohesion and political dissent’.Footnote 49 Icons might even ‘reconstitute a public during a period of crisis or perennial conflict’.Footnote 50 The epistemic-political status of the icon is, in other words, not just to document, but to actively animate a sense of community, identity, and purpose. The image, the political community and those constituting the meaning of images for the public thus enter into a productive relationship that establishes the meaning and authority of each: of what images mean, of who ‘the public’ is, and what it implies to speak with authority about images and the public good. One might ask whether Hariman and Lucaites' theory builds on too much of a commitment to, or preferences for, a liberal, or Habermasian, understanding of politics as deliberation and dialogue among equals and of political community as therefore ultimately always capable of unity and conciliation.Footnote 51 Most of their cases show lines of tension in the American public, but it is nevertheless tensions that can be managed within an American community. The more poststructuralist position of this article is rather that icons are significant precisely because they are articulated in relations to a community or identity, which is inherently unstable.Footnote 52

Regardless of whether icons are theorised as underscoring cohesion or fracture, the discussion above emphasises their widespread circulation, an audience's ability to recognise them and the emotional response they generate. Such images argue Hariman and Lucaites are far and few between. In the case of the United States, ‘fifteen, twenty, maybe thirty at the most across a span of generations’,Footnote 53 and judged from Hariman and Lucaites' case studies it seems that iconic status requires at least a decade of republication. While this obviously ensures that the photographs in question can make a strong claim to being institutionalised, this leaves out ‘instant icons’: images that circulate immediately to a world wide audience generating an emotional response.Footnote 54 Given the desire by many IR scholars to engage with international politics as it unfolds putting up a ten-year window would clearly be unfortunately. Opening up for images to become icons sooner also accommodates what Perlmutter identifies as a more fundamental shift in the 2000s such that ‘in today's media, current history is being speeded up, at least in its photographic portrayals’. In response, he suggests that ‘These new indelible images might be called the hypericons – they pass by fleetingly, gain attention, and then are replaced quickly by new icons.’Footnote 55 As the cases of Abu Ghraib or the falling World Trade Center shows, not all icons in the contemporary media environment are hypericons, as some do manage to institutionalise themselves past the ten-year window. Yet, a larger question is whether changes in media use, information technology, and political identity eventually lead to a different temporality of icon production and forgetting.

Foreign policy, regional and global icons

Moving from a general discussion of the icon to the question of the international icon the first question that arises is what ‘the international’ indeed means. One answer would be that international icons are simply those that comply with the definition of the icon on a global scale. What W. J. T. Mitchell calls ‘world pictures’ are thus ‘globally circulated and instantly recognized icon[s], which requires only minimal cues, visual or verbal, to be called to mind’.Footnote 56 More concretely, I suggest a tripartite differentiation of the international icon into the categories of foreign policy icon, regional icon, and global icon based on how widely an image is circulated and recognised. ‘Foreign policy icons’ are a particular subset of domestic icons in that they depict foreign policy related events situated outside or within the territory of the state. Through their constitution of ‘the foreign’, and thereby the national Self, foreign policy icons bring ‘the international’ into domestic politics, but a foreign policy icon is not necessarily recognised outside of its particular national context. An example is images of ambushed soldiers that question a humanitarian operation but which do not reach audiences in other troop contributing countries. ‘Regional icons’ by comparison are recognised within more than one political community, but not globally. An example of a regional icon is the photo of Bosnian prisoners from 1992 that was widely circulated and emotionally responded to by news media, politicians and activists in Europe and North America. Global icons have, as the name suggests, a circulation beyond the regional. Examples of global icons are ‘Tiananmen Square’ from 1989, ‘Napalm Girl’, and the World Trace Center Towers on 11 September. This tripartite distinction acknowledges that the international system has had and has strong regional structures,Footnote 57 and that some images might be crucial to foreign policy making at the regional level, but not at the global.

One weakness of this distinction is that the circulation of images is hard to quantify, and that it is even harder to measure the extent to which people recognise images, even within domestic contexts.Footnote 58 Another critical question is whether the international media environment is now so transnationalised that a state-centred model is inadequate. Piers Robinson argues in a recent stock taking of work on the CNN-effect that new media technologies have facilitated the creation of a ‘global political sphere’, but that one should also be cognisant of how ‘national, cultural and language barriers still keep most of the world's public attuned to their national media’.Footnote 59 Steve Livingston, another author of key works on the CNN-effect and the international politics of media, holds more radically that developments in the realm of information technology (the internet, cell phones, and satellite uplinks) have lead to a ‘scale shifting’ such that ‘state institutions will be bypassed altogether in networked flows of images, words, and other symbols’.Footnote 60 The blurring of the distinction between producers and consumers imply that traditional understandings of mass media as generating content and political elites as interpreting that content on the one hand and a passive, receiving audience on the other can no longer be sustained.Footnote 61 In the case of ‘Neda’ for example images were sent from someone in Tehran to an Iranian asylum seeker in Holland who uploaded it to Facebook and YouTube from which it was immediately picked up by CNN thus entering mainstream news media.Footnote 62 The online commemoration of Neda further illustrates that political communities may arise around iconic images across national boundaries.

The differentiation of the international icon into the categories of foreign policy icon, regional icon, and global icon is based on patterns of circulation and recognition. Yet, we might also approach the concept of the international icon in a different way, namely by asking how ‘the international’ is constituted through icons and discourses that assign them meaning. As R. B. J. Walker famously put it, the international is not a set of predefined actors or institutions, rather it is a space with a particular temporality, and it is constituted through a series of juxtapositions to the national.Footnote 63 On the inside are politics, ethics, identity, and progress; on the outside are power, war, difference, and repetition. Yet, these dichotomies are not fully stable, and thus there is not a transhistorical, transcultural, universally shared notion of ‘the international’. Thus we might ask how icons are situated within discourses that articulate ‘the international’ and how that ‘international’ constructs identity/difference, Self/Other, universality/particularity, progress/repetition, and reason/barbarism. Who and what, in more concrete words, appear as subjects, objects, actors, threats and opportunities, and with which identities and responsibilities?Footnote 64 To illustrate, this approach to the international asks for example how the iconic image of the burning World Trade Center Towers on 11 September was constituted in terms of who were under attack, who the enemy was, what time the attacker was situated within, and thus whether war or dialogue should be adopted in response.

The impact icons make: text, image, policy

The discussion above has been based on the premise that icons have political significance; the Introduction pointed for example to the impact of the Abu Ghraib photos on American politics and international relations. Taking a closer look at how icons matter politically, how should we theorise the ‘icon effect’? First, we need to clarify our assumptions about the image itself. This article proceeds from the assumption that an image does not provide a foreign policy utterance independently of texts (media, political elites, and others) that ascribe it meaning.Footnote 65 By representing atrocities, violence, and death an image might present itself as a claim that something ‘be done’, but what that ‘doing’ is cannot be deduced from within the image itself. Icons are images that through their widespread circulation function as visual nodal points, they provide a partial fixation within an inherently unstable system of signs.Footnote 66 Yet, even icons do not ‘speak’ foreign policy in the absence of textual discourse. As a consequence, they rely upon text and media for their production and circulation, whether old (newspaper, television, magazines) or new (websites, blogs).

Looking to the literature on icons, media coverage, and foreign policy we find an array of views of what ‘impact’ means. Often these views are implicit rather than explicitly argued and unpacking them is crucial to our understanding of why assessments of icons differ, but also for a wider understanding of how different approaches understand the politics of the icon. One approach to the icon asks whether images, particularly as relayed by news media change foreign policy. This is the general question of the CNN-effect literature, which Robinson recently concluded has found ‘little evidence to date of a media-driven policy U-turn whereby news media coverage has forced unified officials to alter course’.Footnote 67 Work on the CNN-effect has established, more specifically, that two factors determine the possibility of news media to influence the course of policy: the level of political elite-consensus and where an issue falls in terms of high-low politics.Footnote 68 The higher the level of elite-consensus and the more high politics an issue is, the less is the impact of the news media. Given that many international icons relate to instances of war or international crisis, that is, traditional high politics, and that war is often characterised by elite-consensus this apparently leaves little room for media, and hence icons, to impact policy. Political Communication scholars working in this tradition have however expanded the scope of the ‘icon impact’ question asking whether icons influence public opinion on questions of foreign policy and if so if there is an effect on electoral politics. Perlmutter's seminal study of the execution at the 1968 Tet offensive, Tiananmen Square in 1989, and Somalia 1993 found for example that only in the latter case – which brought images of dead Americans to the American public – was there a discernable impact on public opinion.Footnote 69

Yet there are other ways to frame the question how icons impact international politics than whether icons cause a foreign policy shift or whether politicians are punished or rewarded for how they respond to icons. First, even in the case of ‘instant’ icons their effect on policy might not occur within the relatively short timeframe adopted by studies in the news events tradition. Rather, icons might ‘influence public debate in a more indirect and long-term fashion’.Footnote 70 The temporality of the news event tradition is in other words one of immediate impact, yet, what characterises iconic images is their ability to remain in circulation and be emotionally responded to over a longer period of time. ‘Napalm Girl’ for example continues to resurface both in its original form and as a template for editorial cartoons and artwork. As such it is a politically significant ‘sign’ in the visual discursive field even though a direct impact on foreign policy is hard if not impossible to quantify. Second, the fact that political elites might be successful in terms of articulating discourses that accommodate icons does not make the study of icons superfluous. Quite the contrary perhaps as one could argue that understanding such ‘elite disciplining’ of challenging icons is warranted from a normative, democratic perspective. Third, from the perspective of IR the question is not only what determines foreign policy within a domestic setting, or if public opinion is moved by iconic images, but whether images can create, deepen or solve international conflict. This implies a research agenda which includes studies of how state leadership, diplomats, and foreign policy civil servants seek to handle icons – in particular those that generate image crises – in public as well as through diplomatic channels.Footnote 71

Appropriations: the image as intervention

Much work in the fields of Visual Culture, Art History, and Communication have discussed the image's ability to ‘help build or reinforce a moral position’,Footnote 72 not least whether photography can bring atrocities to light in a manner which activates a public response while at the same time not be presenting those suffering as passive victims devoid of agency and dignity.Footnote 73 Judith Butler argued with reference to the move of the Abu Ghraib photos from the news media to the gallery space that this did not simply reproduce the images in question, but ‘gave rise to a different gaze’. This in turn implies that the image ‘can be instrumentalized in radically different directions, depending on how it is discursively framed, and through what media presentation the matter of its reality is presented’.Footnote 74 Scholars in Media Studies and Art History have made particular note of how appropriations – that is, images that work from an existing image to create new ones – can be of ‘critical use’, bring out an image's ‘inherent subversive force’, and act as ‘sites of protest and opposition’.Footnote 75

It is in part through appropriation that an iconic image remains in circulation and that its status as part of a collective visual memory is reproduced.Footnote 76 Theoretically, the icon and ‘its’ appropriations are simultaneously different images and the same: different images because there is not a complete identity between the two and audiences unfamiliar with the icon will be unable to note the similitude; the same because appropriations draw upon the icon. One form of appropriation is where the icon is copied, but where new objects are added or parts of the old image are scratched out. Photographic icons are often appropriated this way, especially as digital technology has made it easier to alter an image. Another form of appropriation adopts the image as a clearly identifiable scene, such as in editorial cartoons using ‘Iwo Jima’Footnote 77 or ‘Napalm Girl’.Footnote 78 Appropriations might also copy parts of an image and incorporate those into new settings. A recent case is the ‘pepper spray cop’ who ‘pacified’ protesters on the campus of UC Davis in November 2011 and who was inserted into famous paintings and photographs which were uploaded to the internet.Footnote 79 Appropriations may stay with the media of the icon or remediate it by moving it to a new one.Footnote 80

The critical potential of appropriations might stem from the latter's ability to bring out something that is located within the iconic image. Dorothea Lange's ‘Migrant Mother’ from The Great Depression is for example used as ‘a stock resource for both advocacy on behalf of the dispossessed and affirmation of the society capable of meeting those needs’.Footnote 81 A critical potential can also reside in the possibility of turning an image against itself, or ‘undoing’ it, what Guy Debord called detournement.Footnote 82 Although the critical capacity of appropriations is more frequently pointed to, it should be stressed that appropriations can also be conservative as when right-wing blogs transformed Fairey's Obama ‘Hope’ poster into an image of Lenin with the text ‘1917’,Footnote 83 or be ambiguous in terms of their critical-conservative stance.

An appropriation can thus be theorised as an intervention in a double sense: into the icon itself and into the discursive field of which the appropriation becomes a part. Theoretically and methodologically, three guidelines for studying appropriations can be suggested. First, like in the case of icons and images in general, the meaning of an appropriation is constituted through textual discourses and intervisual references to previous images. As such we need to read appropriations through the text that accompanies them, that is text on/with the appropriation itself as well as the discourses that may assign meaning to the appropriation. Second, the question whether an appropriation makes a critical intervention needs to be similarly contextualised. What is ‘critical’ is itself frequently a topic of debate and we should therefore, when possible, examine how appropriations are being read as ‘critical’ or not. Third, we should consider the limits of appropriation, that is, whether there are instances where appropriations have been censored and disappear from public view, and whether there are media, genre, and institutional locations where we would expect appropriation but where none have been made.

Based on the theorisation of the international icon above, I propose a three-tiered analytical and methodological strategy which for each step examines the following questions.

-

• Step 1: The iconic image itself

-

• What is the formal composition of the image and what do we actually see?

-

• What ‘factual’ meaning is attributed to the image?

-

• What inter-iconicity is evident or attributed to the image?

-

• When multiple images exist, what might explain this image's rise to iconic status?

-

-

• Step 2: The international status and political impact of the icon

-

• In terms of circulation is the icon a foreign policy, a regional, or a global icon?

-

• How is ‘the international’ constituted through the icon and discourses attributing meaning to it?

-

• What political impact has the icon made and according to which criteria?

-

-

• Step 3: Appropriations of the icon

-

• What is the range of appropriations in terms of media and geographical location?

-

• Which appropriations are singled out as making critical interventions and why?

-

• Which alternative readings of ‘the critical’ might be possible?

-

• Are there discernable limits to appropriation?

-

An application of the international icon framework: ‘The Hooded Man’ from Abu Ghraib

The last part of the article illustrates the theoretical framework presented above through a case study of ‘The Hooded Man’ from the Abu Ghraib files. This image is widely recognised as a global icon in terms of its circulation, it has generated numerous appropriations across a range of media and genres, and there is a substantial literature analysing the photograph, its appropriation, and the political impact it has had. Given space constraints, the analysis will not provide a detailed study of the circulation of ‘The Hooded Man’ or the general debates on the War on Terror or Abu Ghraib, but rather focus on the image's composition and inter-iconicity (in Step 1), its political impact and the way in which it has constituted ‘the international’ exemplified by the immediate response from the George W. Bush Administration (in Step 2), and whether appropriations have made a ‘critical intervention’ (in Step 3).

Step 1: The iconic image

That it was the image of the hooded prisoner that became the globally recognised icon of Abu Ghraib is perhaps surprising (see Figure 1; reproduced in colour in the online version of this article). It is devoid of the nakedness and physical confrontation between prisoners and guards that characterise most of the other Abu Ghraib photos, thus its iconic status cannot be explained by this being the most bodily abusive image. The ability of the photo to embody ‘Abu Ghraib’ is thus related to its formal composition as well as its inter-iconicity. This photo has a ‘striking simplicity at the level of form’,Footnote 84 and a ‘symmetry and contrastive color scheme’, which in itself might make it aesthetically appealing.Footnote 85 Mitchell argues that the hood ‘renders the figure even more abstract and anonymous’ and that the absence of a face reinforces the formal simplicity of the composition.Footnote 86 The image's simplicity has also heightened its potential for appropriation as the freestanding, anonymous, clothed figure with its easily recognisable pose could be transposed into other images and settings. By comparison, another frequently printed photo of Lynndie England with a naked prisoner on a leash entailed a more elaborate scenery. Compared to the other Abu Ghraib images, ‘The Hooded Man’ is according to Mitchell ‘like a Rorschach inkblot, inviting projection and multiplicity of association’.Footnote 87 The absence of nakedness – and the anonymity of the man depicted – might also have made this a more publishable photo, especially in the United States.Footnote 88

Figure 1. The iconic photo of ‘The Hooded Man’, Abu Ghraib 2003.

At the level of inter-iconicity, ‘The Hooded Man’ referred not to one specific image but to several generic icons. Two sets of past icons in particular have been suggested: of lynching in the American South and the suffering crucified Jesus Christ.Footnote 89 Both situate ‘The Hooded Man’ within a history of victimhood and sacrifice, although the hood itself might also be seen as referencing the clansman. Stephen F. Eisenman argues further that the Abu Ghraib photos should be seen in the context of a long tradition in classical European and Western art which ‘extends back more than 2,500 years, at least to the age of Athens’, where the motif is ‘tortured people and tormented animals who appear to sanction their own abuse’.Footnote 90 Other has argued that ‘[t]he serenity of the man on the box, with his outspread gesture of humble sacrifice, appeals to our sympathy and insight’, thus modifying Eisenman's view that the prisoner is put in the position of condoning his own fate.Footnote 91 Which specific inter-iconicity is invoked is thus subject to debate.

The final question at Step 1 is which factual meaning is attributed to the image and what we actually see. This might seem a banal question, but it nevertheless illustrates how ‘facts’ are attributed to images by discourses. First, ‘The Hooded Man’ is usually discussed as ‘an’ image, while there are in fact probably at least five photographs taken from several angles.Footnote 92 These differ, some only slightly in terms of the angle of the arms while others show him in profile or carrying the cardboard box on which he stands out of the room.Footnote 93 The latter photo in particular is breaking with the serenity and potential Christian iconography of the iconic photo and the allusions to violence are less overt.

Second, judged from the image alone, one cannot in fact tell whether it is a prisoner or a guard under the hood. Nor does the image provide us with any clues as to its geographical location other than this is a place that is tiled in soft-tone colours. In terms of time, the cardboard box, wires, hood, and cloth only give us a vague contemporary reference. Although the prisoner is immediately referred to as ‘him’, the hooded and covered body provides no visible signs of gender (there were reports about female prisoners in Abu Ghraib, so this could have been the case) and while the man in the picture later testified that wires were attached to his toes and penis,Footnote 94 these are not visible. As the identity of the man in the picture has subsequently been the topic of some controversy, what is significant is perhaps less the veracity of this claim, but how it has become a fact of the constitution of the meaning of ‘The Hooded Man’ icon. Text needs in other words to inform us that this is from the Abu Ghraib prison, that this is a scene of abuse rather than for example rehearsing for a school play on the history of lynching in the Deep South, and that the prisoner is a man. To ask what we actually see in an iconic image and compare that to established accounts of ‘what the image says’ shows us in short the significance of discourse.

Step 2: Circulation, the international and political impact

The global circulation of ‘The Hooded Man’ is emphasised by numerous publications and debates over Abu Ghraib and the War on Terror still continue a decade after the photos were first made public.Footnote 95 In the terminology developed above, this makes ‘The Hooded Man’ a global icon. As a consequence there are multiple ‘local’ – that is national and to some extent regional – debates and discourses that could be studied. Put differently, ‘the international’ is always constituted from a particular place and by specific discursive actors, even if – or perhaps especially when – those speaking and writing make the claim to be speaking on behalf of ‘the’ international community, humanity, or a similarly universal subject. In that sense, ‘the international’ is always an inherently unstable identity. With this as a theoretical starting-point, how was ‘the international’ constituted by the government who was formally in charge of the Abu Ghraib prison, that is the George W. Bush Administration when ‘The Hooded Man’ became world news?Footnote 96

Subsequent analysis has argued that the Abu Ghraib photos were largely absent from the American 2004 presidential election campaign and that the impact of ‘Abu Ghraib’ on American politics was limited.Footnote 97 Yet, if we look to the first months after the photos became public the Bush Administration responded frequently and often in an emotionally charged register. As Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld put it in his testimony before The Senate and House Armed Services Committee ‘the photos give these incidents a vividness – indeed a horror – in the eyes of the world’,Footnote 98 and President Bush's response was visceral: ‘It makes me sick to my stomach to see that happen’.Footnote 99 What is seen in the photos are ‘horrible, horrible’Footnote 100 and ‘abhorrent’ actsFootnote 101 and locating ‘Abu Ghraib’ on a scale of difference, Rumsfeld goes as far as describing this as ‘the evil in our midst’.Footnote 102 The constitution of ‘Abu Ghraib’ as a sickening product of abhorrent, evil practices is connected to this as an isolated incident carried out only by a few individuals. This is in turn makes ‘Abu Ghraib’ a ‘catastrophe’, something essentially incomprehensible and irrational, rather than a more widespread phenomenon or the product of institutional shortcomings.Footnote 103 Thus, as the President repeatedly argued, this is ‘not the way we do things in America’.Footnote 104 Or, as National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice put it, ‘Americans do not do this to other people.’Footnote 105

The prison guards charged – and later convicted – were of course American in the formal sense of their citizenship, yet in terms of the constitution of ‘the international’ they were located by the George W. Bush Administration as outside of the American ‘inside’. Having extradited those committing the ‘horrible’ acts at Abu Ghraib from ‘America’, ‘the international’ is populated by an American subject privileged vice a vice ‘Iraq’. The hierarchical nature of the American-Iraqi relationship is evidenced by the certainty with which Rumsfeld stated that ‘the truth is that the United States is a liberator, not a conqueror’.Footnote 106 The US has, in short, not only the right, but the obligation to be in Iraq, and it – not ‘Iraq’ or ‘Iraqis’ – has the right to define the American presence as liberation. This effectively leaves little room for ‘Iraqi’ responses other than gratitude, a point underscored by Bush emphasising ‘how decent and compassionate our troops are. I hear stories all the time of people working with orphans or people helping schools be formed or people working to provide medical care for people.’Footnote 107 But not only should ‘Iraqis’ be grateful, they should be cognisant of the difference between American society and the Iraq they inhabited under Saddam Hussein, a difference proven by the fact that those responsible for ‘Abu Ghraib’ are being duly prosecuted. This, Bush explains, stands in stark contrast to how ‘if there was torture under a dictator, we would never know the truth’.Footnote 108 Thus, effectively, ‘Abu Ghraib’ becomes a testimony to the strengths of ‘America’, rather than its weaknesses, and the ‘stain on our country's honor and our country's reputation’ is to make only a temporary dent in the reputation of the United States.Footnote 109 As a consequence of this construction there is no position from which opposition to American presence in Iraq can be legitimately argued. Nor is there a political subject in Iraq – a government or other collective representational actor – worthy of being consulted with or apologised to.Footnote 110

The Bush Administration strove to construct a positive and unambiguous relationship between the Iraqi, the American, and the international community but its discourse was widely contested, especially outside the United States. ‘The international’ in turn became a contested and fractured space with relations of dominance and power where ‘Abu Ghraib’ itself was ambiguously located. ‘Abu Ghraib’ was Iraqi insofar as it became known to a global audience as a prison facility located within the state of Iraq. It was American insofar as those who were in control in the photos – or in some cases like ‘The Hooded Man’ outside the frame – represented the US Armed Forces. And it was international insofar as the photos were constituted as part of the War on Terror fought not only by the US, but by the Coalition of the Willing. The space of ‘Abu Ghraib’ was – and is – simultaneously Iraqi-American-international, yet there is an undecidability at work in this relation: the space was not Iraqi as if it were, the prison would be run by Iraqi authorities, not Americans and the space was not American as this was beyond US territory and the subjects incarcerated non-American. What arise is in turn an ambiguous international space that is US-Western dominated, yet, where key actors from the Bush Administration seek to erase this dominance by constituting their presence as sanctioned by universal values and defence of the Iraqi people. Read through the classical IR dichotomies of inside/outside, politics/power, and universality/particularity, the photos effectively ‘internationalise’ the American presence in Iraq and they demonstrate a space governed in a manner at odds with the liberal universalism claimed by the US government.Footnote 111

Step 3: Appropriations

The debates over what ‘Abu Ghraib’ signified took place not only through texts and speeches, but through appropriations of ‘The Hooded Man’ covering the genres of magazine covers, murals, posters, painting and drawing, cartooning, and installation.Footnote 112 In addition to being the central figure, he features more inconspicuously in backgrounds and off-centreFootnote 113 or in appropriations of other iconic images such as ‘Napalm Girl’.Footnote 114 Appropriations identified and discussed in the academic literature on Abu Ghraib are predominantly set within an American, European, or Middle Eastern context, but that might well be because scholars have devoted less attention to other parts of the world less directly involved in the war in Iraq.

In the attempt to pursue the question how appropriations might act as critical interventions in foreign policy debates, the analysis below is focused on two appropriations of ‘The Hooded Man’. Both show that it might be difficult to provide a clear yes-no answer to the question of an image's critical potential, that is, that these images might be read in ways that underscore openness rather than certainty.

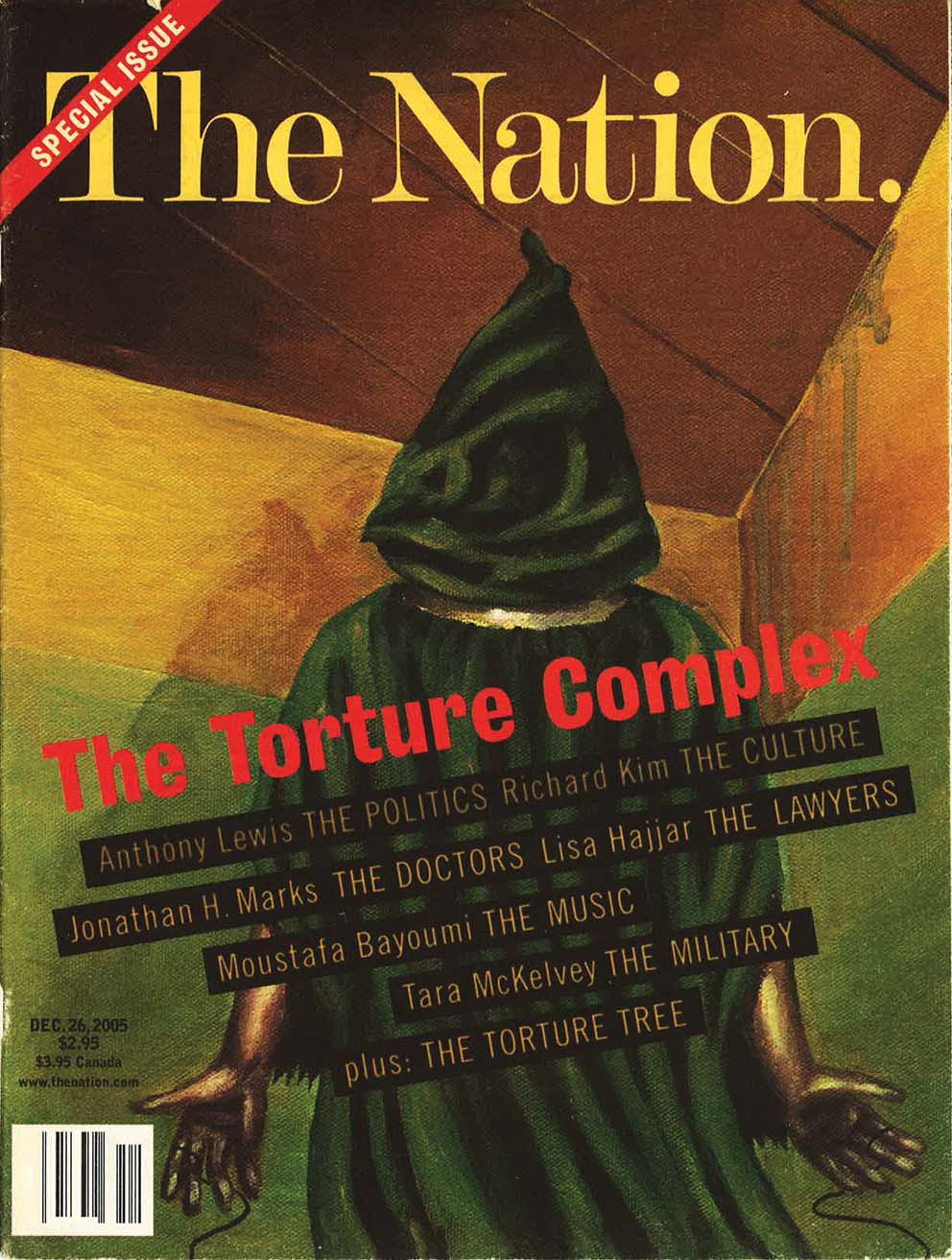

The first example is a 26 December 2005 cover of The Nation by Steve and Janna Brower (see Figure 2; reproduced in colour in the online version of this article). Published more than a year and a half after the photos from Abu Ghraib were released, ‘Abu Ghraib’ itself is not explicitly mentioned on the cover or in the opening Editorial. Yet, the hooded prisoner has come to embody the existence of a ‘new torture complex – centred in the executive branch of the government but with tentacles throughout the country’ including ‘the military, the law, medicine, media, and the academy’.Footnote 115

Figure 2. Steve and Janna Brower, cover of The Nation, 26 December 2005.

Steve and Janna Brower's cover makes a clearly identifiable reference to ‘The Hooded Man’, yet, there are also important compositional changes. We are now zoomed up much closer to the prisoner than in the original photo, and the perspective is one of looking up at the prisoner rather than straight at him. He is being forced up into a corner, the wires are barely visible, and his hands are still stretched out, but at a lower angle. The zooming in has taken us closer, but we are invited to come closer still, either to embrace the hooded prisoner or to see what our inaction is causing him. The striking red headline running across his torso provides a textual linkage between ‘Abu Ghraib’ and a wider ‘Torture Complex’. In terms of the composition of the image, it accentuates the hood, which is draped such that a hole appears where the face presumably is located. Thus we are brought in to personally face the prisoner in a starker way than in the original photo.

Particularly for an American audience, the genealogy of the hood invokes the history of lynching whether the hood covers the victim or the executioner. Yet, the Browers' cover is not only a mediation of the Abu Ghraib icon through the iconicity of one of the most traumatic parts of American history. Another, specific inter-iconicity is constituted through the fact that the cover is itself an appropriation of a 1942 World War II poster by Ben Shahn entitled ‘This is Nazi Brutality’ (see Figure 3; reproduced in colour in the online version of this article). The intertextuality between the two posters implies that those brutalising prisoners at Abu Ghraib – and more broadly those involved in (at least parts of) the War on Terror – are constituted as akin to Hitler's regime.Footnote 116 As David R. Conrad described it decades before Abu Ghraib, ‘[a] hooded handcuffed victim dominates the poster, with a ticker tape announcing the terrible events superimposed on this brave but doomed figure’.Footnote 117 Yet, it is only because of the text that we know this man is doomed: compared to the open, outstretched hands of the hooded prisoner, retained in Browers' cover, Shahn's prisoner's pose is one of knotted, defiant palms. Set within the context of World War II propaganda, this pose opens up for multiple readings and identifications: the prisoner might be the exterminated citizens of Lidice or it might be the fate of all – including Americans – if the war against Nazi Germany is not fully supported. The political discourse of the poster is thus not to succumb but to fight. Reading Brower's 2005 cover through the 1942 poster by Shahn provides the former with a higher degree of resistance as the latter encourages the former to clinch his fists.

Figure 3. This is Nazi brutality, Ben Shahn, 1942.

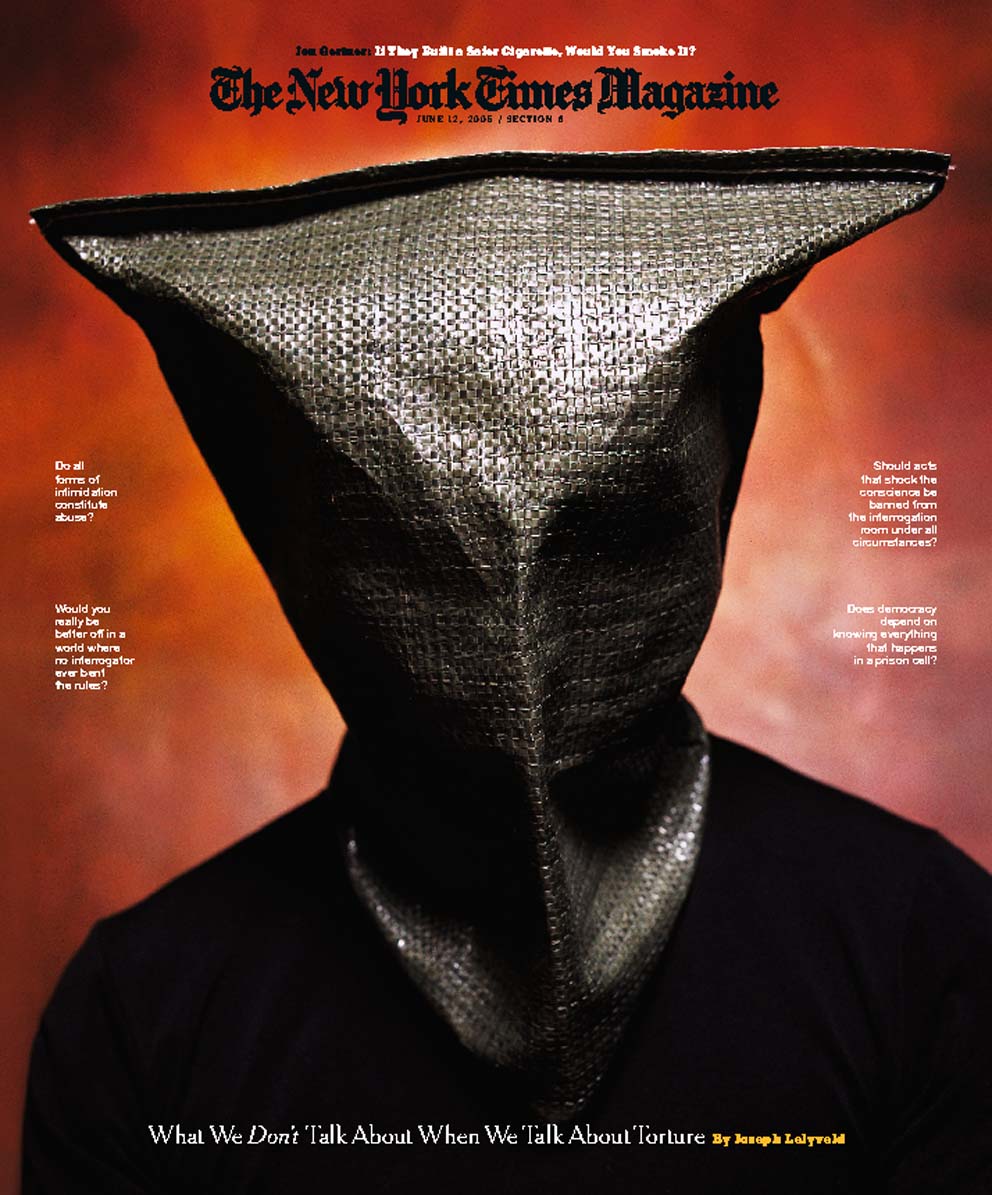

The second example is a photograph by famed art photographer Andres Serrano featured on the 12 June 2005 cover of The New York Times Magazine (see Figure 4; reproduced in colour in the online version of this article). The composition of the cover allocates the hooded man centre stage, the cover story is featured in white font at the bottom of the page while four blocks of questions on the sides of the hooded man's face are barely legible. When read, the questions all evolve around frequently raised issues concerning the use of torture, such as ‘Would you really be better off in a world where no interrogator ever bent the rules?’ In Erina Duganne's reading of the image ‘the dramatic lighting; the intense, red-painted background; and the shallow depth of field lend the figure an ominous and dominating presence’.Footnote 118 Duganne holds further that the use of words on the cover such as ‘intimidation, interrogation, prison, and torture’ means that it is ‘unclear whether one should read the figure as the subject or the object of torture’.Footnote 119 This ambiguity is, however, resolved as Duganne determines that the intervisual connections to Abu Ghraib ‘encourage one to read the hooded figure as suffering and in pain’, a reading, she argues, which is further supported by the essay within the magazine.Footnote 120 Duganne's position is noteworthy because it illustrates the theoretical-ontological position that texts are superior to images: Serrano's image is disciplined by the words on the cover and by the essay located inside the magazine. It is also a reading which presumes that the appropriating image is inferior to the appropriated as Serrano's figure becomes one of suffering through its inter-visual reference to Abu Ghraib. These assumptions deprive the image of the potential to resist the textual discourses it is supposed to illustrate or validate, it also deprives new images of the capacity to unsettle previous ones by appropriating some of the formal characteristics and shifting others. The argument here is not that Duganne's reading of the cover is wrong, rather that it is only one among several plausible ones. Another such reading would be to see this less as an image of abjection than a menacing avenger and allow ‘him’ to resist the text surrounding him.Footnote 121 Reading ‘The Hooded Man’ through Serrano's image, the former may thus be rallied to resist.

Figure 4. Andres Serrano/The New York Times Magazine, 12 June 2005

The hooded prisoner has been remarkably resilient in terms of not running into boundaries of appropriation. Perhaps the strongest concern would be that the image is so easily cut out, inserted and circulated that it, as Mitchell puts it, becomes reduced to ‘an empty signifier or ‘brand’, like a corporate logo’.Footnote 122 Ten years after its first publication, that does not however seem to have happened. Unlike Che's famous portrait, ‘The Hooded Man’ is not used to sell T-shirts, mouse pads, vodka, and a host of other consumer objects.Footnote 123

Conclusion

This article has identified and introduced the international icon to the field of IR. International icons are freestanding images, widely circulated, emotionally responded to, and seen as representing significant historical events. They are found across a variety of genres, produced and reproduced by a range of media, and they are frequently appropriated and thus inserted into genres beyond the one in which they originated. The ‘international’ in international icons can be approached from two perspectives: at the level of circulation and recognition they come in the form of foreign policy icons, regional icons, and global icons; at the level of meaning production we should ask what ‘international’ spaces and subjects are constituted by those discourses that ascribe political significance to the icon. The article has argued that we should take a broad view of how icons matter to world politics rather than restrict it temporarily to the time immediately upon publication or spatially to domestic or comparative politics. Moreover, we should consider the icon and its appropriation as interventions into foreign policy discourses while keeping the question of whether such interventions are critical open.

This article has illustrated the content and applicability of the international icon framework through the case of the hooded prisoner from Abu Ghraib. Thus, it is perhaps appropriate in conclusion to point out that this is not the only international icon that could be subjected to further study. Looking to the past decade, the following images mentioned above would for example qualify as either global or regional icons: Kurt Westergaard's drawing of the prophet Muhammad, the charred contractors from Fallujah, Shepard Fairey's ‘Hope’ poster of Barack Obama, and the video of Iranian activist ‘Neda’. More recently, and from the category of generic rather than discreet icons we find the images of the victims of the chemical weapons attack in Syria in August 2013 or the photos of the more than 360 people who drowned off the coast of Lampedusa later that year.Footnote 124 Yet, because iconic images continue to circulate through reproduction as well as appropriation, the study of international icons and their impact on world and domestic politics is never finished. ‘Napalm Girl’ for example is continuously republished in works dealing with the Vietnam War and its aftermath and it is appropriated in engagements with current events, for instance in political cartooning on the Abu Ghraib scandal. Thus, to return to ‘The Hooded Man’, we should expect to see him invoked as debate on the War on Terror and American foreign policy past the presidency of George W. Bush – and Barack Obama – continues. Given the iconic status of this image, it is also likely to be appropriated in commentary on events not directly related to the war in Iraq.

The international icon framework laid out in this article might also be subjected to further theoretical elaboration and possibly revision. First, the need for a research agenda on global icons is accentuated by the growth in new media technology and the ensuing transformation of who can produce and circulate images. Cell phone technology has for instance produced a genre of citizen journalism that was unheard of only two decades ago. The instantaneity of communication and the reach of audiences beyond one's own state of presence challenge IR scholars across all perspectives to rethink key concepts and assumption. Specifically, in terms of the international icon, this raises the question whether the distinction between ‘national’ and ‘international’ icons is itself in need of theoretical adjustments as media audiences and producers loosen their territorial anchoring. Another question is whether the speed of image production and circulation is now such that icons might more easily be produced, but that it might be harder for iconic images to establish themselves in the long term. Were that the case, our response should not be to abandon the concept of the icon, but rather to retheorise the role of temporality. Second, most examples discussed in this article have been either global or if regional involved the United States and/or Europe as one of the regions in which an image has achieved iconic status. This raise the question whether there are dynamics – in terms of media, politics, and circulation – outside of the West that call for a more nuanced theoretical framework than suggested here.