We the women

We the women who toil unadorn

Heads tie with cheap cotton

We the women who cut

Clear fetch dig sing

We the women making

something from this

ache-and-pain-a-me

back-o-hardness

Yet we the women

Whose praises go unsung

Whose voices go unheard

Whose deaths they sweep

Aside

As easy as dead leaves

Grace Nichols, I is a Long Memoried (London, Karnak House, 1990)

Introduction

In this article, we aim to make a feminist intervention in the debates about the nature of the everyday in International Political Economy (IPE) by situating our discussion of the everyday within the conceptual framework of social reproduction – the socially necessary work that is central to the production of life itself.Footnote 1 We set out an analytical framework that makes visible the co-constitutiveness of social reproduction and everyday life by showing how space, time, and violence shapes and remakes both. This allows us to highlight the importance of gendered social reproductive labour in the maintenance of everyday life, and the costs attached to this, the structures of power that constrain, govern, and discipline everyday life, as well as the gendered forms of agency that serve to reshape the everyday. In so doing, our analysis builds upon the work that feminist IPE has done as a corrective for the exclusions of much IPE scholarship by exposing how global economic restructuring operates to reproduce gendered and racialised inequalities and asserting the need to uncover the micro level processes through which these transformations take shape.Footnote 2 Thus, our intervention can be usefully engaged alongside texts such as V. Spike Peterson’s A Critical Rewriting of Global Political Economy in which a feminist IPE is developed via a ‘structural and macro orientation through which differences, specificities and localities can be read’.Footnote 3 Ours is very much a complementary project – albeit one in which our starting point is not global structures; rather we seek to read social reproduction as everyday life in order to inform an analysis of global/transnational phenomena.Footnote 4

To build our argument we first outline some conceptual clarifications in relation to social reproduction and the everyday. This conceptual discussion, while in certain respects covering familiar ground for many feminist political economy scholars, connects our analysis to a wide and varied audience in IPE, International Relations (IR), and feminist theory and thus provides groundwork through which we seek to open up debate. We then examine the three building blocks of our argument – spaces of social reproduction, its temporalities, and the gendered structural violence that underpins the everyday. Through this discussion we seek to better understand both the rewarding and the disempowering nature of social reproduction. We further argue that this non-recognition has material, harmful, consequences that are manifested in different spaces and temporalities. In the final section of the article we discuss how gendered agency is employed to challenge exclusions. This article does not draw upon any single piece of empirical fieldwork, rather it makes a theoretical intervention into debates on the everyday. We do, however, draw upon empirical examples throughout the text as powerful illustrations of how everyday life is social reproduction, and how the policing of a social-reproduction/production binary offers only partial accounts of the everyday.

Social reproduction as the everyday

We define social reproduction as a concept that encapsulates all of those activities involved in the production of life. This includes biological reproduction, the work of caring for and maintaining households and intimate relationships, the reproduction of labour, and the reproduction of community itself – including forms of social provisioning and voluntary work. Social reproduction also includes unpaid production in the home of goods and services and the reproduction of culture and ideology that stabilises (as well as sometimes challenges) dominant social relations.Footnote 5 In this article we acknowledge the important conceptual work on both social reproduction and on the everyday and argue that it is through bringing the two into conversation that we can form a more capacious understanding of ‘how we live’Footnote 6 in contemporary capitalist societies. We situate the labour of social reproduction by developing understandings of everyday life in IPE through the intersecting vectors of space, time, and violence (STV). We then hope to advance the field through capturing the links between production and social reproduction – how these are continually being undone, but also redone, in the ways that people produce, reproduce, live and discursively mark their lives, both in the market and domestic spheres, in different social manifestations, and through varied struggles to reshape their lived landscapes. This approach not only challenges how notions of the everyday have emerged within IPEFootnote 7 but also highlights the wider dangers of leaving social reproduction unrecognised. As Silvia Federici suggests, in an era of unmitigated capitalist expansion this misrecognition itself reflects ‘a new round of primitive accumulation’ based upon ‘a rationalization of social reproduction aimed at destroying the last vestiges of communal property and community relations’.Footnote 8 Bringing the everyday and social reproduction into view within the same conceptual frame means that we can begin to dismantle understandings of both as discrete, and to recognise their centrality to the functioning of the global political economy as a whole. Indeed, we claim that social reproduction is the everyday, and no discussion of the everyday can do without integrating the concept, the analytics, and the practices of social reproduction.

Building our analysis on important previous debates, we note that within classical traditions of political economy an account of production as an activity that supported social life prevailed and, in this sense, social reproduction was seen to be at the centre of the reproduction of life in all its complexity.Footnote 9 Thus, production was seen as serving social reproduction rather than the other way around. While much Marxist work positions social reproduction as outside the central contradiction (the extraction of surplus value by capital from labour),Footnote 10 we find in Frederic Engels’s writings a recognition of the significance of women’s work in the home, which initiated an analysis of capitalism’s dependence on this labour and its necessary role in the sustainability of capitalism.Footnote 11 This argument was taken up in the 1970s discussion of ‘wages for housework’.Footnote 12 Although controversial on the grounds that it tied women too closely to caring roles, this was a first attempt to think about the everyday spaces of social reproduction (the household), alongside the temporalities of social reproduction (its drudgery, repetition, and routine). The lack of compensation for social reproduction can also be understood as a form of structural violence that also exposes women, through their dependency on a male breadwinner, to direct forms of violence.Footnote 13 Of course, this literature was also limited by the way in which it generalised social reproductive labour under Western capitalism by white middle-class women as the norm and was inattentive to a wider spectrum of identities.Footnote 14 More recent work by feminist scholars has also sought to redress the exclusion of social reproduction from production by paying attention to the costs of denying the value of this labour as a denial of human rightsFootnote 15 and as a ‘depletion’ of individuals, households, and communities such that harm accrues to those who do this unvalued work.Footnote 16 Moreover, the current, wide-ranging feminist literature on social reproduction provides insights into both the richness of the everyday political economy as well as its intersectionality – social reproductive labour is increasingly understood as constructed at the intersections of race, gender, nation, age, and class.Footnote 17 And yet, very little of this feminist literature specifically engages with the concept of the everyday. Such a lacuna needs to be addressed not least because a significant everyday turn is underway within both IPE and IR. This serves to reveal the importance of mundane, banal, ‘insignificant’ practices and objects – challenging a perceived macro-level bias in international studies and enables us to look beyond the very logics of politics/economics that dominate the ‘big questions’ of these fields.Footnote 18

The everyday itself is often mobilised in academic writings as a ‘fuzzy’ and imprecise concept that is impossible to pin down: it is ‘strangely elusive’, and ‘resists our understanding and escapes our grasp’.Footnote 19 The seeming lack of precision accorded to this term is, in certain respects, part of its appeal to scholars in that it provides a basis for interdisciplinary dialogue and serves to move the study of IPE in novel directions.Footnote 20 But there are limitations to leaving a term so loosely defined. Such analytical imprecision can mean that issues of embodied identities and lived experience are as easily excluded from discussions of the everyday as they are included. Abstracted at a meta-level, we overlook the tangled boundaries of gender, race, class, and sexuality that animate our everyday worlds as lived experience. Moreover, in developing our argument we note that there is a risk that discussions of gender are seen as merely providing ‘descriptions’ rather than ‘theorizations’ of the everyday.Footnote 21 Presenting social reproduction as central to understandings of the everyday – conceptually, analytically, and empirically – is for us then a critical issue.

Approaches to the everyday within IPE are many and varied.Footnote 22 One survey of this literature has suggested that IPE work on the everyday is characterised by either a focus on the agency of non-elite actors or the mechanisms through which everyday life is governed and disciplinedFootnote 23 – a division that feminist work does not easily conform to given the longstanding feminist methodological concern with the need to reveal gendered structures of power alongside expressions of voice and agency (a discussion we return to in the final section of this article).Footnote 24 Of course, themes of subversion and resistance play out in a wide range of everyday IPE studies; they are in many ways the recurring motif of such texts and reflect the enduring influence of scholars such as James C. Scott and Michel de Certeau.Footnote 25 It is also certainly the case that writings on everyday life in IPE focus attention on the many and varied ways through which it is transformed and governed with the rise of capitalism and urbanism – a concern that reflects the longstanding influence of Henri Lefebvre’s writings on everyday life.Footnote 26 Lefebvre’s work draws attention to the routines and rhythms of everyday life as well as how the everyday operates as a manifestation of the sphere of consumption that maintains capitalism.Footnote 27 Although the everyday is for Lefebvre a sphere of consumption, he also makes us aware of contestation and change: though sexual desire and love, play, and celebrations;Footnote 28 in so doing he calls for the production of an unalienated everyday of autonomous and thinking human beings. Lefebvre’s work certainly serves as one jumping-off point for thinking about a political economy of everyday life.Footnote 29 Feminist scholars have, however, pointed out that Lefebvre’s theorisation of everyday life does not focus on the gendered materiality of production, reproduction, and consumption and that gender features in his depiction of everyday life largely as an account of how ‘boredom’ through domestic incarceration is daily experienced by women.Footnote 30 While we do not have the space in this article to discuss at length Lefebvre’s work and the feminist critique of it, we acknowledge the importance of this work in two ways: social reproductive work can be a drudgery and if not socially recognised and redistributed in an equitable way it produces alienation for those engaged in it – often valorised as ‘mother’ or ‘parent’, on the one hand, and framed through specific policy and governmental techniques which incarcerate, make dependent, and marginalise, on the other. Second, Lefebvre points us to the importance of holding our understanding of space and time together, in a productive tensionFootnote 31 as we do in our tripartite framing of social reproduction as the everyday. In addition, we also underline the violence of everyday life through the non-recognition of social reproductive work and the physical, mental, and socially depleting effects this produces.Footnote 32

Hence, through the STV framework, we emphasise the co-constitutiveness of social reproduction and the everyday. We argue that this is important to rethink core IPE concepts such as production, the market, and labour as well as to develop a socially necessary practice that is revealed in the ways in which the work of social reproduction plays out temporally, spatially, and in the context of gendered structural violence. The STV reading, moreover, provides an insight into how social reproduction is not only done everyday, but also how it is central to understanding everyday life under global capitalism – it is mundane labour, involving drudgery, routine, and repetitive tasks, even as it can be fulfilling, emotionally rewarding, and consensual.Footnote 33 It also capaciously envelops production and reproduction in a ‘unitary’ account – one that gives equal weight to the production of commodities and the reproduction of labour.Footnote 34 In terms of practice, social reproduction remains a site of struggleFootnote 35 – both at the everyday/grassroots scale and in terms of ‘high’ politics as policy – over how and when it is organised, regulated, recognised, and/or valued, over who undertakes this labour and why, and over the wider political implications of the non-recognition of social reproduction in conventional economic analysis. Social reproduction is not therefore understood as the locus of repressive and unchanging gender relations, but one that has the potential to challenge and transform the power relations that serve to devalue social reproductive labour. This allows for thinking through how agency and resistance matter to an understanding of social reproduction as well as the everyday. In short, we see a feminist political economy analysis as one that captures both the reproduction of mundanity (‘everydayness’) alongside a recognition of the everyday as a site of agency and resistance.

Methodologically, a key aspect of feminist work has been to acknowledge the importance of everyday experience. According to Sandra Harding, ‘If we want to understand how our daily experience arrives in the forms it does, it makes sense to examine critically the sources of social power.’Footnote 36 Feminists have also underscored the importance of different experiences of the everyday,Footnote 37 foregrounding the intersectional identities of class, race, ethnicity, and sexuality of women as well as of those who research their experiences.Footnote 38 In doing so, feminist work often serves to reveal a picture of everyday life marked not simply by routine and familiarity, but also by different gendered forms of insecurity and violence.Footnote 39 Accounts such as Cynthia Enloe’s The Big Push, for example, centralise women’s voices and experiences and thereby pose a challenge to dominant ‘relations of ruling’ that have persistently silenced women’s voices and standpoints.Footnote 40 Consequently, feminist work reveals a more embodied understanding of global politics and political economy that ‘make visible something of the mess, pain, pleasure and pressure of everyday life’.Footnote 41

Building on the above discussion, we argue that the task of theorists of the everyday is to reveal the sutures that bind the local with the global, the private, with the public in the sphere of labour – productive and social reproductive. This is not to say that we are not concerned with the ways in which social reproduction is carried out and regulated and, specifically, the critical role of the state in mediating and sustaining those gendered social relations that make possible the invisibilisation and/or undervaluing of social reproductive work and how this state power has been internationalised and transformed in the context of capitalist economic restructuring.Footnote 42 These issues are of course critical, and enmesh the everyday. They reveal to us how social reproductive work is done, the conditions under which it is undertaken, and what costs are attached to its doing – that is, the ‘depletion through social reproduction’Footnote 43 that occurs spatially, temporally, and in relation to violence. There is a need to examine, we argue, the intimate practices and struggles involved in the day-to-day construction of the productive-social reproductive binary, in spaces of the domestic and private. We now turn to a more detailed discussion of the STV framework and its three elements.

Space, time, and violence: a tripartite framework

In this article, building on the debates on social reproduction and the everyday, we employ three analytical lenses – space, time, and violence – through which we develop this feminist approach to the everyday. We argue that social reproduction, like market-based production, is emplaced within social space whose boundaries are fluid and relational, in a continuum of time and rhythm, which attracts both structural and individual violence and in turn provokes resistance to such violence through agential mobilisations. Below (Figure 1), we visually depict the relationship between these three aspects of the everyday political economy and call it the STV framework for understanding social reproduction as the everyday. Everyday life is, we argue, carried out in relational spaces that both include and exclude, connect, and marginalise. In this sense, as Lefebvre has argued, it is embedded in the social relations of embodied, everyday human practices; it is then a social product as well as a concrete abstraction.Footnote 44 We suggest that space is relational and a gendered terrain of the everyday. In terms of time, we reflect upon the rhythms of gender-segregated social reproductive work, generating strains of sociality that become evident in the negotiation of space as well as in the everyday violence, both structural and domestic. The STV framework, embedded in regimes of class-, racialised-, and sex-based exclusion, is therefore manifested and experienced differently, in different social contexts. We now outline this tripartite framework through a discussion of its key elements.

Figure 1 Space, time, and violence framework.

Spaces of social reproduction and/of everyday life

Space is not only a physical location; it is composed of the gendered social practices that occur across and within it. We begin our discussion with a focus on the space(s) of the household. But such a focus should not be read as a suggestion on our part that social reproduction is neatly ‘containerised’ within the household, even though it remains important in most people’s everyday lives. Rather, it echoes Dorothy Smith’s commitment to studying the everyday as ‘embedded in a socially organized context’Footnote 45 but which must also be understood as ‘an actual material setting, an actual local and particular place in the world’ (and a world that is studied by researchers who are themselves located in their own everyday lives as ‘bodily and material existence’).Footnote 46 Thus alongside a discussion of the household, we also explore the relationships between social reproduction and mobilities. Through a focus on the everyday act of travel for work we seek to reveal how social reproduction and the depletion that occurs as a consequence operates beyond the household as social reproduction is stretched and shifts across multiple sites.

Households are produced ideologically – we only need to mention discourses of mothering, the ‘housewife’, and the family (ideals that are infused with particular class, sexual, and racialised logics). We are not suggesting a normative attachment to the model of the nuclear family, nor do we seek to reify the everyday space of the household. Following our discussion of Lefebvre above, we must consider the connections between capitalist modernisation and the forging of public-private divides in which the everyday comes to be ‘set apart from public space … no longer identified with the anonymous sociality of the streets’.Footnote 47 Thus the practice of the everyday cannot simply be captured within a public-private binary,Footnote 48 but at the same time, the placing of the household firmly within the realm of the ‘private’ has enduring political and economic effects. These effects include the non-recognition of social reproduction as well as the prevalence in economic development planning of assumptions regarding the existence of nuclear households headed by male breadwinners and often supported by state ideologies promoting women as primarily homemakers, mothers, and reproducers of the nation rather than active citizens with claims on the state.Footnote 49

Feminist scholarship has been central to unpicking these binaries, revealing, for example, how the household is not, and never has been, a closed space separate from capitalist production but exists as a site in which work, labour, and social reproduction co-constitute the everyday. Reproduction of labour and its governance link inextricably the economies of intimacy and of the market. As Maria Mies’s pioneering Marxist feminist work on Indian homeworkers showed, the global economy entangles relations of domesticity in the spaces of the household through gendered regimes of labour.Footnote 50 Greater visiblisation of how households exist as actual sites of productive and simultaneously social reproductive work matters, not least because of the forms of precarious working that characterise home-based work. In this sense, the production of household space is sustained through scalar hierarchies which render households as outside of political economy analysis even as the inside and outside continue to be co-productive.Footnote 51 Yet, a (Fordist) myth of the neat division between production and social reproduction persists. Thus even as the household becomes ever more marketised – that is, as household labour is ‘bought in’,Footnote 52 as development donors promote home-centred micro-enterprise in poor countries,Footnote 53 and household consumption is viewed as the key to global prosperityFootnote 54 – we can still identify the enduring effects of those gendered binaries that render social reproduction less important.

While the household is a site of imbrication of production and social reproduction, it also has a materiality that exists in the physical walls of the house itself. This is a materiality that matters not simply because the walls of the house may serve to obscure household relations from view – actually and politically – and discursively demarcate the boundaries of the public and the private, but also because so many of the struggles of everyday life revolve around securing adequate shelter and maintaining and provisioning of the home as well as oppressive regimes of property that exclude many women.Footnote 55 Iris Marion Young draws attention to the gendered work of building homes – highlighting how women tend not build homes but ‘make’ homes: ‘those who build dwell in the world in a different way from those who occupy the structures already built, and from those who preserve what is constructed’.Footnote 56 The way in which the built environment shapes our everyday and the centrality of the home itself to this is revealed, for example, in Farha Ghannan’s study of urban resettlement (into high-rise apartment blocks) in Cairo, whereby the actually existing closed doors of the new apartments merit particular attention, serving as they do to impose a new boundary between public and private and refashioning gender relations around the normative nuclear family.Footnote 57 Hence the lived experience of home is shaped by complex axes of power; household relations will, on the one hand, constantly spill out of the place of family residence into gendered communal living and leisure spaces, but at the same time, the affective and the patri-authoritative place of the household generates ‘multiple sovereignties’ of governance as familial relations are continually (re)regulated and disciplined by, for example, a male head of household or community elders.Footnote 58 This then extends Lefebvre’s view that social space is allocated to reproduce class structures (in the city); bringing social reproduction centrally into our analysis of space reveals space as private/political as well as a gendered politics of space.

Further, the concept of the household as an economic unit has been radically reimagined, and even challenged, under conditions of global economic restructuring. What have been termed ‘global households’,Footnote 59 created by the ongoing feminisation of labour migration, operate to reformulate patterns and practices of caring across different locations of the world – practices that are becoming ever more reliant on extended family networks and the buying in of paid and barely paid domestic labour.Footnote 60 Global production and care chains serve to stretch households spatially across national boundaries even though at the same time households retain their local positionality as sites within which social reproductive labour predominately takes place. Nonetheless, that so much of the remittances generated by household members working overseas go into the building, maintenance, and provisioning of homes underscores the way in which the global reimaginings of households are tethered materially to the home itself.Footnote 61

One concrete way of demonstrating the power of the STV framework in the context of the household is to discuss (im)mobility to and from work. Travel is done over space, requires not only time (thus stretching the margins of work-time), but also affects the body (increased tiredness), the sense of security (safe or unsafe travel can decrease or increase the sense of insecurity), reputations (that is who can and who can’t ‘loiter’ in public spaces), family status (the visibility that comes with going out to work, rather than being a home worker), and wages (money spent on travel as a subsidy to employers). The city is a gendered space and traversing it a gendered experience. Everyday travel to work can be more stressful, more risky, and more imbued with violence for women. Travel is always mediated by class – the poor in particular need to travel long distances on inadequate public transport to get to work.

Mapping space and positioning women and men within its ambit is no easy task. How would we know the experience of space and make judgements about it? One way of experimenting with researching space is through ‘shadowing’ women who travel to work.Footnote 62 The idea here is to map the space/time negotiation that millions of women make every day to and from work. This allows us to see not only the physical effects of negotiating space in different modes and by different women but also mental and wider health effects. Take for example, a lower middle-class woman travelling by public transport in New Delhi in winter. The days are short, darkness falls quickly; high levels of pollution mean that even during the day the air is acrid and cold and exacerbates breathing problems; and the buses and metro are packed with commuters who are desperate to climb on/in these vehicles so as not to be late to work or home. Groping and other sexual violence is attendant upon travelling, but so is the increased anxiety that comes with confronting this every day. Shadowing women in New Delhi as they travelled to work, noting the time it takes, and taking pictures as triggers to memory as we interviewed them, allowed us to understand these pressures that are faced everyday by women negotiating public spaces as they also carry out their social reproductive tasks.

As we show in the final section of this article, while domestic violence has been much researched, as has been violence in the public space in terms of war, it is often the everyday ‘transgressions’ that stem from women being seen as ‘out of place’ (occupying spaces outside of the household) that results in forms of violent disciplining. As Shilpa Phadke, Samera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade have argued,Footnote 63 issues of violence should not just focus on ‘safety’ in the occupation of public spaces: while we need to stress the structural violence that makes such an objective desirable, we also need to focus on the larger spatial contexts within which women live and work. This leads them to study women and leisure (itself often experienced in small margins, especially by those engaged in social reproductive and paid work) as occupation of public space, and to consider the politics of how different groups inhabit space in different ways in their leisure time. Their emphasis on loitering (or ‘time pass’) – is an everyday feminist response not just to issues of access to public space/right to the city, but also through purposeless yet pleasurable engagement in and with public space – and one that can be positioned also as a critique of the hypertemporalities of late capitalism (see below). We can also point to the role of more ‘purposeful’ occupation of space as an exercise of agency and as a resistance strategy – be it in terms of feminist activism such as ‘Take Back the Night’, ‘Slut Walk’, ‘Why Loiter?’, or ‘Hollaback!’Footnote 64 to undermine the violent policing of female bodies in public spaces, or in terms of the politicisation of private spaces via housing occupations and other, oftentimes female-led, collective activism around housing evictions.Footnote 65 It also challenges gendered regimes of women’s work in the household – to spend time on herself undermines the narratives of ‘good housewife’ engaged in domestic and care labour.

Time and social reproduction

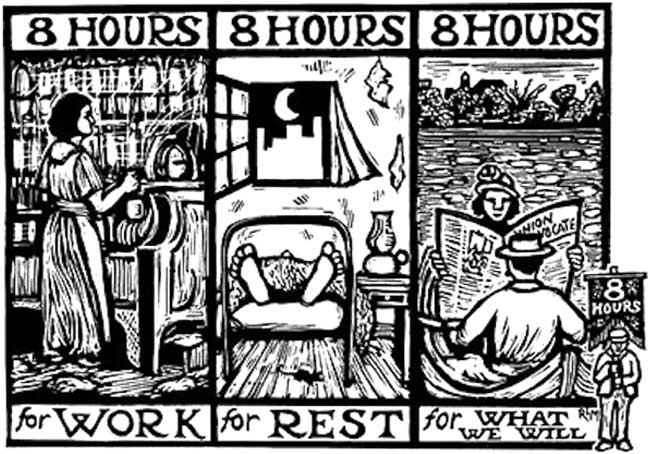

Our thinking about time and the everyday was initially shaped by our responses to this powerful image of the eight-hour day in private and public spaces by the artist Ricardo Levins Morales.Footnote 66 The eight-hour day, that is, a day divided into three temporal zones – work, rest, and ‘for what we will’ – emerged in the writings of the early nineteenth-century social writer Robert Owen and became an important rallying point for trade unions in the early twentieth century. It is an issue also taken up in Kathi Week’s book The Problem with Work in which the eight-hour day movement is invoked in the development of her arguments that shorter working hours (for all – not just for women) is a feminist demand.Footnote 67

If a gendered analysis of space prompts us to frame, as we have done above, leisure as a political occupation of space, then a similar analysis of time alerts us to the fact that, ‘[t]he politics of “who gets what when and how” involves access to disposable time as well as other scarce resources. This “politics of time” is linked in complex ways with women’s changing and variable domestic, economic, and political situation.’Footnote 68 Of course, when we look at the eight-hour day image (Figure 2), as critical feminist scholars we immediately see the problems. Where does social reproduction fit? In the eight-hour rest period, who is getting up at night for the baby? It would appear that the rhythmic temporalities of household life sit at odds with a model of daily life that has been set by the regularities and certainties of Fordist production. If we are seeing the emergence of global households then what does that do to time? Consider, for example, the overseas Philippine care worker who waits until midnight to Skype her children back home – she is active in her global household not only as a remittance sender but in terms of the time spent on the social reproductive labour of transnational motheringFootnote 69 – she is depleted by the ever-expanding responsibility that she takes on for social reproductive labour within her own and her employer’s household.

Figure 2 Eight Hours by Ricardo Levins Morales.

Social reproduction takes time, time that is disregarded as work time. Research employing time use surveys (TUS) has emerged as an important methodology (involving diaries, observation, interviews by field workers, and group discussion) and provides important data on the centrality of social reproduction to women’s daily lives. Focusing on time in this way also demonstrates the interdependence of paid and unpaid work within the household. To provide an example, based on studying 3,000 households Who Cares for Us Footnote 70 was a TUS mapping of unpaid care work in Tanzania in 2006. The results were not surprising – that women spend most amount of time on unpaid care work and only slightly less than men on what under the rules of the UN System of National Accounts is called ‘productive’ work.Footnote 71 The survey also pointed to the fact that hiring domestic workers lightens the load on women of the household and that where women are in employment it is more likely that domestic help will be hired.Footnote 72 In other words, time is a resource that women in paid work can buy in; as a commodity it can reduce the burden of everyday labour for some women at the expense of increasing it for others. A strategic focus on time as commodity in the context of the everyday then allows us to see how depletion through social reproductive labour is built into the everyday social economy of the individual, households, and communities and how gendered norms of care secure these discrepancies in different kinds of work. As Diemut Elisabet Bubeck notes, often the vision of free time and time abundance ignores the time-consuming nature of care work, which is dependent on social interaction and relations of power within the household.Footnote 73 The Who Cares for Us survey was significant in that it made a distinction between the ‘24-hour minute’ where multiple tasks carried out within the same time frame were given equal weight, as opposed to the ‘full minute’, where only one task was carried out in a period of time. This also helps question the linearity of time.Footnote 74 What the 24-hour minute then allows us to do is to visualise time sideways – in everyday multitasking. It is the recognition of the overlapping nature of time spent on different activities within the home that leads writers such as Kathi Weeks to suggest that demands for shorter hours can only be truly radical and/or emancipatory if they recognise social reproduction as work.Footnote 75 This is particularly relevant if we also take into account the combination of paid and unpaid work done by women and, for many, the travel between these two sites of work. Travel time can be seen as the arch that connects the everyday unpaid social reproductive and paid work and tells us a great deal about the neglect of everyday gendered practices in the framing of debates on labour and time.

An emphasis on the need for shorter working hours in order to grant people the freedom, to do what they will (‘unbounded time’)Footnote 76 is found in writings focused on notions of a developing post-work economy.Footnote 77 This is a useful idea, but it is limited because it ignores not just social reproduction, but also what Isabella Bakker and Stephen Gill have called the intensification of social reproduction under conditions of disciplinary neoliberalismFootnote 78 –something that is evidenced in terms of the expansion of markets for domestic work or increased family responsibility for older people’s care and childcare, which is related to rising market costs, rising levels of household debt, and the cutbacks in state provision of services. In this context, methodologies such as TUS are important in terms of the recognition that they grant to the overlapping nature of time spent on different activities – an issue that appears to be extremely pertinent to discussions of home-based work and microenterprise development in which assumptions are frequently made about women’s ability to take on extra work within the home. Valerie Bryson’s work on the feminist politics of time thus underscores a need ‘to recognise the importance of temporal rhythms outside the commodified clock time of the capitalist economy, in which time is equated with money and the time needed to develop human relationships has no place’.Footnote 79

Such an approach to time involves consideration of how the everyday of social reproduction offers up opportunities for us to think of time otherwise. Should the rhythms and routines of everyday life be seen merely as repetition and drudgery, or do they provide an escape from commodified clock time? Does a focus on the temporalities of the everyday provide a way of reimagining and valuing social reproduction? How might we use time demands to challenge both the intensification of capitalist discipline as well as those gender ideologies that sustain the normative family. In recognising this (for example, in terms of the TUS that exposes the fallacy in the assumption that that women’s time is ‘infinitely elastic’)Footnote 80 we see how everyday life can also be a deeply repressive site. But recognition of time spent on social reproduction also creates potential for resistance. For us, this time as resistance should not be seen only as taking the form of simple acts of agency designed to resist the temporalities of capitalist life (the foot dragging observed in Scott’s work for example)Footnote 81 but, as Weeks argues, it needs to be fully infused with an overtly feminist ethic.Footnote 82 Time must be recognised as a feminist issueFootnote 83 and resistances can be understood as ‘the possibility of gaining a measure of separation or detachment from capitalist control, imposed norms of gender and sexuality and traditional standards of family forms and roles’.Footnote 84

The discussion in this section illustrates the many ways through which time and space are of course inseparable – we spend time in spaces, and occupying spaces needs time. It is the imbricated nature of time and space that we are querying in the context of social reproduction, which includes not only care work, but also leisure time to repair ourselves, to stem the depletion through social reproduction that so many face. Thus feminist scholars are raising important questions about the temporalities of everyday life. Here we have mentioned work on time use and time as a feminist demand. Other aspects of time/temporality that could be explored in this context might include: the intersections between gender and generational time (including the role of care work in late age, care for the young by the elderly and care for the elderly by those who already have extensive childcare responsibilities – the so-called ‘sandwich generation’); the imposition of ‘dead time’ – the queues, waits, and spells in immigration detention that mark the fate of those fleeing war and structural violence; notions of timeliness and its centrality to capitalist production (including the forms of just in time working and zero hour contracts that have come to characterise the conditions of work under late capitalism); as well as the relationship between time and the state’s role in maintaining particular gender orders (especially in terms of issues such as maternity or paternity leave).

The structural violence of the everyday

Our third focus concerns how gendered violence underpins the everyday. Here we see violence as regimes of labour, law, and policy that secure the boundaries of the public and the private, of property, systems of rule-making and of justificatory ideologies of separation and segregation, where boundaries of race, ethnicity, and sexuality are created and defended by violent acts. As Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has argued, white civilisational discourse places brown women at the mercy of white men as their saviours from violent brown men.Footnote 85 Violence then manifests at the level of the everyday/everydayness with consequent harms. This is an understanding of violence that is necessarily structural, but also one that recognises the significance of individual experiences of violence in developing an understanding the everyday political economy. Ours is an approach that in many respects resonates with the call made by Jacqui True for feminist IR scholars to look beyond the war zone as a site of gender violence, and instead to (re)focus attention on the many and varied violences of the ‘peacetime’.Footnote 86 But more than this, our approach specifically situates social reproduction – and the depletion through social reproduction that occurs in everyday life at its centre through a focus on gendered harms. As feminists have argued, there are harms of non-/mal-recognition of gendered exclusions.Footnote 87 Harm can be conceptualised in the context of the everyday in different ways: as physical and mental harm to the individual, household and community, emotional and discursive harm, and harm to citizenship entitlements.Footnote 88 We can thus study violence and the harm that it generates at both structural and experiential levels although both are imbricated. Violence serves to connect gendered rule within both the private and the public sphere. It also intensifies harm at moments of crises – war, economic, and social collapse for example.Footnote 89 Violence operates over space and time – boundary wars can be conceptual, institutional, but also spatial and fought discursively, through exclusionary laws and policies but also with guns and bombs; disciplining, challenging, and reshaping these can also invoke violent moments of confrontation and resistance in the everyday. As we have argued elsewhere, global governance institutions have displayed a propensity to present violence against women as an economic ‘cost’ without examining how the structures and processes that enable violence against women to take place are rooted in the contemporary global economic system.Footnote 90 Here we build on this critique to show how understandings of everyday violence might be embedded in broader structures of economic and social power.

We have argued that the relationship between women’s subordination in the household and forms of harm/violence is often understood largely in terms of the discussion of domestic violence.Footnote 91 This is important, of course, in order to understand, as Veena Das notes, how ‘everyday life as a site of the ordinary [has] buried in itself the violence that provided a certain force within which relationships moved’.Footnote 92 Domestic and public violence and the threat of violence against women is used to regulate and govern private and public spaces, which has led many radical feminists to claim that ‘[the threat of] rape has played a crucial function … of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear’.Footnote 93 Less attention is paid to how global political economic transformations play out in households in ways that both empower women as well as disempower women, in many cases increasing the threat and exercise of violence against them.Footnote 94 For example, a study of so-called ‘honour’ crimes in India and Pakistan found that one motivating factor for households and community disciplining of young women and men who transgressed boundaries of caste and class in romantic relationships was the fear that the liberalisation of the Indian economy, increasing migration of young men and women to cities and the easier access to ‘Westernised’ cultural media, would lead to the erosion of traditional gendered practices of marriage. The performance of this violence – through open community ‘courts’, of public beatings, and home incarceration – was also suggestive of the elision of governance of communities with the governance of polity – caste-based village councils (khap panchayats) being allowed to decree punishment with complicity of the local government.Footnote 95 The persistence of ‘honour’ crimes thus demonstrates how gendered power is exerted in everyday life but also takes shape within neoliberal transformations to state rule taking shape under neoliberal capitalism. Likewise in the US context, Madelaine Adelman recounts how state welfare systems operate via the endurance of what are deeply heteronormative familial ideologies concerning both the capitalist ‘family wage’ and (neo)conservative ‘family values’. One result of this is a social welfare system that serves to trap women in situations of domestic violence and invisibilises the harms that they experience.Footnote 96

By emplacing everyday violence in the context of the wider social economy we can also examine the structural violence of non-recognition and its consequent harms as revealed in the links between the everyday, the state, and the global regimes of non-recognition of social reproduction. For example, Gross Domestic Product is an important analytical tool recognised globally by nation states to secure distinction between production and social reproduction, which is then employed to generate distinctions of entitlement of citizenships – as taxpayers or welfare recipients – as well as to address economic and political crises through (de)mobilisation of gendered labour. A key insight of feminist scholarship on violence then is that the nation-state and production-reproduction are sutured together through both consent and violence – and that both are gendered through the ways in which multiple gendered sovereignties operate not to end violence but to redistribute it.Footnote 97 This redistribution, we would argue, can be seen in different modes of the global political economy, which frame women’s everyday experience – as workers, in public spaces, and in ways in which the negation of their contributions to the state/economy relegates them to the margins of social life.

It is useful to examine the pervasiveness of violence within feminised zones of work in the global political economy by examining women’s experiences as workers. By situating factory or domestic workers within broader sets of social reproductive relations, it is possible to point to the costs and harms that are experienced by female workers in low paid, labour-intensive work. Most notably, feminist IPE has long been concerned with revealing the gendered nature of global economic restructuring, especially at times of crises, and the position of women employed in global production chains, global factories, and global care chains.Footnote 98 A focus on the experience of violence by women factory workers adds an important dimension to this work, and ought to be central to the development of a feminist political economy approach to everyday violence not least because of the tendency to equate women’s entry into paid employment with forms of ‘empowerment’ that undermine patriarchal household relations. If we consider Diane Elson and Ruth Pearson’s classic work on this issue,Footnote 99 we see how gender relations are not merely ‘decomposed’, but also ‘recomposed’ and intensified when women enter into paid employment. Thus, we could point to the experience of sexual harassment at work and how harassment is oftentimes overtly utilised as a way of disciplining workers.Footnote 100 Indeed, violence in the global factory must also be understood in ways that recognises how the emergence of women into the labour market in certain parts of the world has involved a ‘scaling-up’ of forms of informal and homeworking to the global economy that serves to reproduce the structures of domination and inequality of the household in the workplace.Footnote 101 Important to mention here also is the violence of working conditions in which women’s labour is deemed ‘disposable’ and the work itself entails considerable consequences in terms of workers’ physical and mental health.Footnote 102 These are violences of everyday life that operate as a depletion through social reproduction and alongside gendered logics of labour disposability under capitalism. The evidence of everyday experience when emplaced within broader gendered economies of social reproduction reveals much, then, of the multilayered violence of everyday life.

Shaping the everyday: the intertwining of agency and risk

In our tripartite analysis of the everyday as that constituted through time, space, and violence we do not wish to imply a structural predominance. We have tried throughout to incorporate a discussion of agential mobilisation in our analysis, but perhaps it is useful to provide further elaboration regarding the work that agency does (and does not do) within our framework. Our starting point in developing this discussion is to note that the rhythms of social reproductive labour are agential, productive, but also risky. In the everyday IPE literature, ‘relational tactics’,Footnote 103 ‘defiance, mimetic challenge, axiorationality’, and ‘weapons of the weak’ find prominent space.Footnote 104 Social reproduction, as we have shown above, has to be reimagined if the spatialities, temporalities, and violences attached to it are to be challenged. In the words of Federici, ‘If our kitchens are outside of capital, our struggle to destroy them will never succeed in causing capital to fall.’Footnote 105

Much of the feminist work on agency has not started from analysing the place of individuals in the social landscape; rather the social landscape has been integral to the analysis of individual agency: as the hinterland of colonialism, as the field of capitalist production, and as the space of social reproduction.Footnote 106 This suggests, as we have above, that time, space, and violence are integral to the theorisation of agency and therefore to social reproduction as the everyday. However, we also resist the valorisation of agency that often bubbles underneath some of feminist as well as critical IPE literature.Footnote 107 Walter Johnson has argued that the focus on agency has come to obscure reflection on the consequences of human actions, on the one hand, and judgement about such actions, on the other;Footnote 108 we argue that it also obscures the costs of these actions. In opening the field of feminist politics to agents and actors that are not only ‘overtly’ resistingFootnote 109 oppression and exploitation but also reimagining the social relations of production and reproduction, feminist work has long argued that autonomy and agency are both situated and not untethered from the social landscape. The choices that we make, however rational (or axiorational), are situated choices and therefore the shifts in social landscapes, the lengthening of temporality of making judgements, or the rupture caused through violence will change our choices, judgements, and decisions. But does not, Matt Davies asks, ‘overt resistance … imply a break from the everyday?’Footnote 110 Does it not rupture the everydayness, the givenness of the rhythms of life, expose some to danger, make some heroes and others villains, and be contingent on struggles about reshaping social reproduction elsewhere? Rather than reifying agency and ‘foreclosing the question of how subalterneity is produced’, we point to the critique of the valorisation of the local space as the stage of everyday agency – whether in terms of reproducing social relations through celebrating festivals, excommunicating those who transgress, or crossing communal boundaries of love and marriage to defy the settled norms of everyday and indeed reproduction life – might be far more fraught;Footnote 111 the intimacy of spaces can make for intimate violence. As Sumi Madhok and Shirin M. Rai argue, ‘risk is the inherent danger that dwells in the moments of transgression of these social relations; it disciplines agents and attaches itself to defiant bodies and social spaces where acts of defiance are performed’.Footnote 112 Finally, we cannot pay attention only to gender as a single axis – agency ‘is always so in ways that intersect with hierarchies of class, sexuality, and race’.Footnote 113

This complex and gendered understanding of agency is important when we think through what it means to exercise autonomous agency in contexts that are imbued with structural violence over time and space. We have to recognise that in the very moment of exercising agency we are also taking risks – risks that are productive, but can also expose us to gendered violence within both the domestic and public spaces. The argument here is that ‘while not acting might prolong social injury, strategizing for change needs to involve attention to the parameters of power within which agential subjects seek to act’.Footnote 114 In this sense, we distinguish our analysis of agency from John M. Hobson and Leonard Seabrooke’s;Footnote 115 within the STV framework, everyday agency does not necessarily lead to transformation and reshaping of the political and economic environment, although that might be the case, and often the ambition. Rather, everyday agency is exercised to maintain the structures of power – through violence both direct and indirect, structural, physical, and symbolic – as well as to negotiateFootnote 116 and challengeFootnote 117 these. The possibilities of transformation are mediated by the attendant gendered risks to individual and collective agents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we argue that it is imperative to integrate, conceptually and empirically, the theorisation of social reproduction in the everyday/everyday life. We argue that the inseparability of production and social reproduction is evident in a focus on the mundane, the banal and the rhythms of everyday life and that social reproduction and the everyday are imbricated. The STV framework helps us to demonstrate how we can empirically and methodologically research these concepts, and suggests a way through which the everyday can be reconstituted through gendered readings.

In this article, we have argued that viewing social reproduction as the everyday and everyday as social reproduction allows us to hold production and reproduction together, demonstrate how the mechanisms of control and of oppression bridge the need to connect both these through reproducing spatial, temporal, and violent social regimes and how these can be sustained as well as challenged through agency exercised in different scales and registers. Much work needs to be done to empirically develop this insight. The STV framework might help us do this. Take for example how, first, (im)mobility connects time, space, and violence; by examining in particular the issue of travelling to work we have suggested how this contributes to the depletion of workers through anxiety, physical, and mental stress, and through gendered disciplinary practices such as sexual harassment and worse. But (im)mobility also tells us something about everyday temporalities (the dead time of the commute to work every day for example, or waiting in queue for permits to cross lines of conflict for procuring everyday essentials of living) as well as understanding the particular spatialities of these journeys. If travelling to work poses serious questions about everyday practices and violence, these are also present in the way in which women’s presence in public spaces for leisure is seen as bodies as being ‘out of place’ – leisure in public spaces then becomes another marker of unequal gender relations and the discursive and physical violence attendant upon it. Second, it shows how we might visualise space and time in relation to violence. Why are certain spaces seen as ‘safe’ for some and ‘dangerous’ for others; why is it that the household, which for so many women is a site of production and reproduction, insecurity and violence, continues to be reified as an appropriate everyday space of decent living? If time and space are deemed to be unruly and dangerous, so are the sexed bodies that occupy these – public discourse about women’s dress, demeanour, and independence discursively constructs ‘dangerous women’ whose occupation of certain spaces at certain times undermines the social norms of domesticity and therefore makes them the targets of ‘justifiable’ disciplinary violence. Third, the STV framework invites reflection on what it means to connect understandings of structural violence to space and time. How might work-time (both working time and the tempos of the workplace) be seen as a form of violence? How might the absence of recognition for or invisibility of types of work be a form of harm and how does this intersect with other forms of injustice centred on race, nationality, age, caste, and class? In so doing we recognise that a feminist analysis must retain a commitment to bringing together both – a structural analysis of the gendered experiences of the everyday and the acknowledgement of a transformative agency. Issues of welfare policies, citizenship, and conditions of work become important here, as do the embodied modes of production/social reproduction. The struggles to make visible and recognise the imbricated nature of these are both empowering and risky. STV framework allows us to focus on both.

The STV framework, through treating social reproduction as the everyday, suggests a possibility of not rupturing the lived everyday experiences of women. This framing can then prevent a refraction of the public and the private worlds, the marketised and non-marketised economies of work and care; it insists that there is a gendered politics of the everyday because social reproduction is the everyday.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their extremely constructive engagement with this article, which greatly helped us to clarify our arguments. Thanks also to Stuart Elden, Alex Nunn, Jeremy Roche, Adrienne Roberts, Ty Soloman, and Mat Watson for their useful advice and/or comments.