INTRODUCTION

In this vivid (albeit rather clichéd) account, the town secretary of Antwerp, Cornelius Grapheus, describes the confrontation of two groups of thirteen jousters in a tournament on the Grote Markt, the market square of Antwerp, on 15 September 1549:

It looked as though the horses were flying. One saw lances breaking violently; one heard the sound of the harnesses; one saw the crests of the helmets with the plumes fluttering through the air. And although they all behaved bravely, everybody agreed, to the utmost delight of his father, that our prince behaved most bravely of all.Footnote 1

The teams were led by two young but high-ranking nobles, Floris de Montmorency (1528–70), Lord of Hubermont, and Emanuele Filiberto (1528–80), son of the Duke of Savoy. It was no ordinary tournament, since one of Emanuele Filiberto's team members was Prince Philip of Spain (1527–98), heir to the throne, and Philip's father, Emperor Charles V (1500–58), was among the spectators. “For the perpetual memory of this royal joust,” the town administration of Antwerp decided to hang the coats of arms of Prince Philip and the other jousters in their main meeting room. These were the real shields with which the tourneyers identified themselves and that were put on the architrave of the special platform made for the judges of the jousts.Footnote 2 What was eternalized in the town hall was not only the presence of the prince and his entourage in the town but also their chivalric endeavors performed in the most emblematic public urban space.

The tournament in Antwerp formed part of a series of elaborate chivalric encounters organized on the occasion of the Joyous Entry of Prince Philip in the Low Countries in 1549 and 1550. These tournaments tend to be treated as courtly events, without taking into account their wider social and political context.Footnote 3 The term courtly event can, of course, be interpreted in two ways: an event organized at the court—that is, in or around a princely residence—or an event predominantly involving members of the court—that is, the princely household. During his entry, Prince Philip met not only his new citizens but also the future members of his household for the first time.Footnote 4 Like his predecessors in the expanding Burgundian and Habsburg composite state, he was confronted with the serious task of dealing with the nobilities in the constituent territories.Footnote 5 Not all nobles could be offered a position in the prince's household or were elected to the highly prestigious chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece. Princes thus needed to deploy other strategies to foster cohesion among the nobles, who had different social and geographical backgrounds, as well as different professional careers, and tournaments should perhaps be viewed in this light. Hence, the question arises as to whether tournaments around the middle of the sixteenth century were indeed purely courtly events, or if they functioned as a performative tool to enhance cohesion. Obviously, tournaments offered excellent opportunities for all these men to demonstrate their knightly virtues and their armorial skills vis-à-vis their peers and the prince. The nobles with the most chivalric behavior could distinguish themselves. At the same time, however, the collaboration among the combatants required in several types of combat went beyond the idea of pure individual performance. In other words, ritual violence practiced in a (semi-)public sphere could play a role in the bonding together of the nobility in the Habsburg composite state.

The knighthood and the nobility of the Habsburg composite state have not yet been studied in an encompassing and comparative way, but rather within the respective research traditions in, for example, Spain and the Low Countries. Where the Low Countries are concerned, existing studies of the nobility in the second half of the sixteenth century are regional in focus; there is as yet no in-depth study of the nobility of the first half of that century that pays attention to issues of chivalry and vivre noblement.Footnote 6 However, intensive contacts between the Spanish and Netherlandish nobilities were established following the marriage of Philip the Handsome (1478–1506) and Joan of Castile (1479–1555), in 1496. Particularly during the couple's two journeys to Castile, in 1502 and 1506, the interaction between nobles from the different territories intensified. Philip's successor, Charles V, made an explicit effort in his nomination policies to the Habsburg institutions to create a “transnational elite,” in the words of René Vermeir.Footnote 7 Furthermore, in the 1530s and 1540s the nobilities from the Iberian kingdoms and the Low Countries fought together during military campaigns in Tunis, Piedmont, Provence, Cleves, Guelders, France, and even Saxony.Footnote 8 The advent in the Low Countries of Prince Philip, as a new ruler who was relatively unacquainted with the subjects of his northernmost territories, heralded the beginning of a new era.

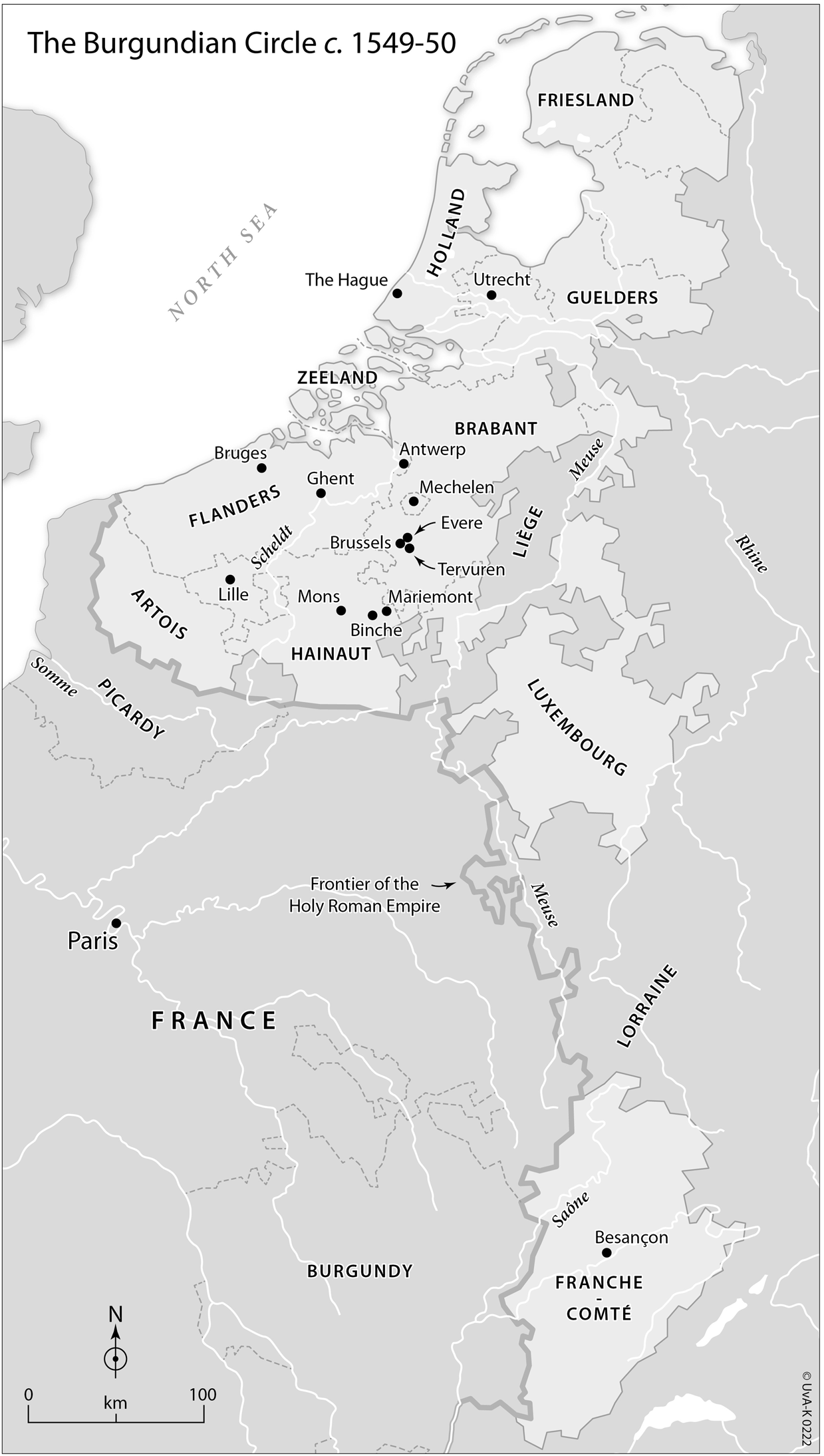

The tournaments of 1549–50 offer a unique opportunity for examining the extent to which these occasions were instrumentalized in a process of mutual recognition and social integration of the nobilities from the different parts of the Habsburg composite state. Although Italian and German nobles also constituted an important part of the households of the Habsburg monarchs, they are not the primary focus of this article. The Burgundian nobles from Franche-Comté, however, are included, since for more than a century they had established firm links with noble families from the Netherlands. Moreover, Franche-Comté formed part of the so-called Burgundian Circle already created by Maximilian I, and reaffirmed by Charles V at the Imperial Diet at Augsburg in 1548 (see fig. 1).Footnote 9

Figure 1. Map of the Burgundian Circle, ca. 1549–50. © UvA-Kaartenmakers.

The first section of this article discusses the current historiography on Habsburg tournaments and nobles, along with the possibilities and limitations of the available source material. The second section focuses on the first definition of the term courtly event—that is, the locations where the tournaments took place, while also taking into account the geographical origins of the tourneyers. I will then, in a third section, turn to the social aspects of the term, examining the relationship between the tournaments and the princely households. Finally, in the fourth section, I will demonstrate how the different tournaments’ forms and combat techniques furthered the engagement of the tourneyers in both the martial and the social sphere.

RECOUNTING NOBLES

Tournaments and chivalric events have been much neglected in recent historical analyses of the military and political role of the nobility in late medieval and early modern Europe. In his seminal book on premodern dynasties, Jeroen Duindam pays more attention to the administrative and governing talents of princes and their noble officers than to their military or martial skills. Tournaments are only mentioned in the context of the dissemination of “court culture to distant enthusiasts”—that is, through festival books.Footnote 10 In their book on warfare and state formation in England and the Low Countries, Gunn, Grummitt, and Cools do stress the influence of war on the power relations between the nobility and the sovereigns of England and the Habsburg composite state in the first half of the sixteenth century. They concentrate, on the one hand, on the formal structures of the state (nobles as governors, military commanders, and members of the Golden Fleece), thus showing the integration mechanisms of the apparatus. On the other hand, mainly through the analysis of narrative sources (military treatises, family histories, poems, etc.) and visual display (portraits, heraldry, architecture, funerals), they show how war influenced noble identity.Footnote 11 However, they do not pay attention to the relationship between war and tournaments, nor to the role of tournaments as a marker of noble identity.

Glenn Richardson, in his book on the famous tournament of the Field of the Cloth of Gold, in 1520, with the participation of both Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France, maintains that tournaments “became increasingly courtly entertainments” from the fifteenth century onward. Nevertheless, he stresses the military importance of this particular chivalric event, since the some 250 English and French noble participants could practice their skills in various types of combat in peacetime.Footnote 12 Malcolm Vale and Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly even demonstrate that because tournaments involved a wide variety of combat techniques, both on foot and on horseback, they had military relevance well into the seventeenth century.Footnote 13 Sidney Anglo and Noel Fallows oppose this view, arguing that the joust was increasingly “irrelevant to contemporary warfare” and that “the activity was an end unto itself, with the result that jousters trained above all to be good jousters.” Moreover, Fallows stresses that tournaments in general were more “a theatre of display” than a realistic exercise for mounted combat.Footnote 14 Admittedly, the role of mounted cavalry declined in the sixteenth century, and the joust, bound by all kinds of rules (described in treatises analyzed by Fallows), does indeed seem far removed from the experience of battle.

The main source for the analysis of the tournament cycle of 1549–50 is the chronicle El felicíssimo viaje del muy alto y muy poderoso principe don Phelippe (The most joyous voyage of the very high and very mighty prince Don Philip), printed in 1552 and written by Juan Cristóbal Calvete de Estrella (d. 1590), who accompanied the heir to the throne, Prince Philip, on his grand tour through the Low Countries.Footnote 15 Calvete de Estrella was appointed to Philip's household in 1541 as “master of grammar to the pages” (maestro de gramática de los pajes), but soon afterward he was also assigned the task of educating the heir to the throne. He acquired hundreds of books for the prince's library and was generally acknowledged as one of the court's outstanding humanist intellectuals. Born in Aragon from a noble family and raised in Cataluña, he worked in Castile for most of his life, and was thus familiar with the world of the nobility of almost the entire Iberian Peninsula. What is more, in 1547 he himself was granted the title of infanzon, which meant recognition of his noble descent.Footnote 16 This implies that the chronicler must have been acquainted with the chivalric events he described and their noble participants.

Calvete de Estrella does indeed mention all the participating nobles by name, which shows that he must have had lists of participants or descriptions made by heralds, clerks, or painters to be able to produce such a seemingly exact record.Footnote 17 Of course, it is not sure whether his lists are complete, but his report is the best source there is concerning the participants in all tournaments (see appendix 2). In addition to his text, I will use another description of Philip's journey through the Low Countries, written (in Spanish) by Vicente Álvarez and published in 1551.Footnote 18 It contains considerably fewer details and lists of names, but it is interesting for the descriptions of some of the tournaments. For the tournaments in Binche and Mariemont, no fewer than six other contemporary descriptions are available: two in French, two in Italian, one in German, and another one in Spanish.Footnote 19 These accounts are very useful for comparing with the lists of Calvete de Estrella, especially the detailed description by an anonymous German chronicler, printed in Frankfurt in 1550, which makes clear that our Spanish chronicler omitted five participants of the Mariemont tournament.Footnote 20 For the events in Antwerp, there is a detailed description in Dutch by Cornelius Grapheus, secretary of that town, printed in 1550 and already quoted at the beginning of this article.Footnote 21

The fact that these narrative sources were written in Spanish, German, Italian, and French, and that most of them were printed, shows that the heroic and chivalric deeds of the Habsburg nobility in general, and of Prince Philip in particular, were communicated to an audience all over Europe. One has to be aware of the authors’ propagandistic intentions and should not take everything they entrust to paper at face value. Hence, Gonzalo Sánchez-Molero characterizes the report of Calvete de Estrella as a “magnificent project of political and cultural propaganda.”Footnote 22 Concerning the “impression management” of the Habsburg rulers, Peter Burke reminds us that “images, whether literary or visual, should not be studied . . . as unproblematic ‘reflections’ of reality of the time.”Footnote 23 Texts and images produced at the court were media events in themselves. Charles and his son Philip were well aware of this and used these events consciously to fashion a public self-image built on classical and medieval traditions. For this reason, in addition to these narrative sources I have analyzed the available financial accounts of the cities (Antwerp, Ghent) and domains (Binche, Tervuren) where tournaments were organized, as well as a specific account of the festivities in Binche and Mariemont.Footnote 24

THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE TOURNAMENTS AND THE TOURNEYERS

From Calvete de Estrella's report it becomes clear that between 1 April 1549 and 11 May 1550 fourteen tournaments were staged (see table 1 and appendix 1).Footnote 25 However, there was a peak between July 18 and September 15, when no fewer than eight chivalric events were organized. This means that in these two summer months, on average, one could watch a tournament somewhere in the Low Countries every week. The most extensive survey for the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, made by Évelyne Van Den Neste, reveals that there were only two other years (1362 and 1454) in which eight tournaments were organized in the principalities of the Low Countries.Footnote 26 In other words, the frequency of the events in 1549–50 is remarkable, and even unique for the full timespan from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century.

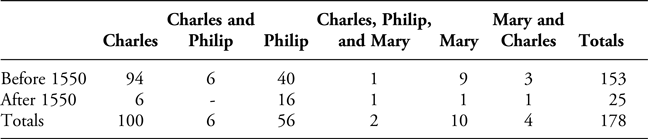

Table 1. Number of tournaments in 1549–50

The overview of the locations of the tournaments (table 1) shows that the Duchy of Brabant stands out: nine of the fourteen events were organized in Antwerp, Brussels, and EvereFootnote 27 (near Brussels), where the very first tournament, a mock battle, was organized (fig. 1). Second is the county of Hainaut, where four spectacles were held in Binche, and finally Flanders, with one tournament in Ghent.

The choice of these cities seems to be at odds with the main hypothesis of this article, that the tournaments aimed at the integration of the nobility. Why was not a single event staged in the recently added duchy of Guelders (1543), or in the age-old residence of the Binnenhof in The Hague, in the county of Holland?Footnote 28 The distribution of the tournaments was certainly uneven for several reasons, of both a political and a practical nature. The economic and political shift from Flanders to Brabant in general, and from Bruges and Ghent to Antwerp and Brussels in particular, explains the concentration of the events in Brabant.Footnote 29 The duchy was geographically situated at the center of the Low Countries and, moreover, encompassed the two centers of political decision-making in the first half of the sixteenth century: Brussels and Mechelen. From these political centers, excellent lines of communication existed with the major towns in other principalities. Philip arrived in Brussels from the southeast, via Waver and Tervuren, on 1 April 1549.Footnote 30 The town became virtually the center of his inauguration tour, since he traveled to other parts of the Low Countries from there. The Coudenberg Palace, in Brussels, had become one of the most popular residences for successive Burgundian and Habsburg princes in the fifteenth and first half of the sixteenth century.Footnote 31 In the grounds of the palace, a jousting field was created in the garden (fig. 2), where four chivalric events were staged (see appendix 1). However, not only the facilities of the princely residences but also the markets in the towns of Brabant and Flanders (for luxury goods and armor, for example) were better able to meet the requirements of the Habsburg court and nobility than their counterparts in the north. In 1549, armorers from Brussels supplied hundreds of clubs, swords, pikes, and lances for the tournaments in Binche and Mariemont, in Hainaut, and the town administration of Antwerp ensured that there were sufficient coats of armor for the tournaments organized during Philip's entry in September 1549.Footnote 32

Figure 2. View of the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels with the jousting field and park, ca. 1531–33. Drawing for a tapestry, ascribed to Bernard van Orley. © Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek PK-T-2047 (CC BY 4.0).

The organization of no fewer than four tournaments in Binche and the nearby residence of Mariemont within a time span of one week (see appendix 1) had to do with the involvement of Mary of Hungary (1505–58), who acted as governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1531 to 1555. In 1545, Charles granted her the town and lordship of Binche, which had military significance on the frontier with France (see fig. 1) and had even suffered a siege by the French dauphin two years earlier. The architect Jacques du Broeucq reconstructed the castle, which the governor had decorated with works of art and tapestries made or designed by artists like Michiel Coxcie, Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Titian, and Rogier van der Weyden, to the admiration of many contemporaries. Moreover, in nearby Mariemont Mary had built a luxurious hunting lodge, with extensive gardens occupying a space of about 90 hectares.Footnote 33 Next to this maison de plaisance a miniature fortified castle was built—with four towers of brick and wood, and surrounded by a moat—for the specific purpose of staging a mock siege.Footnote 34 All the work was finished before the visit of Charles and Philip in the last weeks of August 1549. Indeed, Mary was the central figure in the organization of the inauguration tour, and she seems to have gone to great efforts to ensure its success:Footnote 35 it was she, “with the ladies of her household,” who welcomed Prince Philip to the castle of Tervuren earlier that year, on April 1, the formal start of his trip through the Low Countries. For the organization and staging of the tournaments, however, she received support from many nobles from her own household and that of her brother Charles. Their entourage included experienced jousters from the Iberian Peninsula such as Juan Quijada de Reayo, who in 1548 wrote a treatise on jousting called Doctrina del arte de la cavalleria (Doctrine of the art of chivalry).Footnote 36

The choice of cities in Brabant and Hainaut to host the tournaments can thus be attributed to both the political importance of the residences and the available infrastructure that could easily be adapted for putting on the events. That said, only five of the fourteen chivalric events were staged in the courtyards or gardens of princely residences, whereas seven took place in the main squares of the towns of Brussels, Ghent, Binche, and Antwerp (see appendix 1 and fig. 1). Another two events were mounted outside the city walls but were accessible to the general public. It is clear that even the spectacle in Mariemont was more of a public than a purely courtly spectacle, since Calvete de Estrella remarks that “the roads and fields [to Mariemont] were crowded with people . . . not only from Binche but also from all other neighboring places.”Footnote 37 Grapheus mentions that for the Antwerp tournament of 15 September 1549 a double barrier was constructed to protect the tourneyers “against the hustle of the crowds.”Footnote 38 The city dwellers—especially the urban elites and higher middle classes of the town—were an ideal target for the prince: they could watch the events and sometimes even participate in them, admire the courtly behavior of their social superiors, and, if necessary, acknowledge or approve princely power.Footnote 39 The “role of the common citizenry should not be underestimated,” as Margit Thøfner has convincingly shown, and encounters between princes and their cities should not be viewed as spectacles in which propaganda from above was simply “consumed” by the audience.Footnote 40

Viewed in this light, the tournament cycle of 1549–50 was more of an urban than a courtly event, although it is true that some encounters were performed in more exclusive venues. Despite the strong concentration on the cities of Brabant and Hainaut, the topography of the tournament only partially overlaps with the origin of the tourneyers. All chroniclers reflect their awareness of the geographical diversity of the participants. Calvete de Estrella, for example, rightly notes that in Binche “the most important knights from Brabant, Flanders, and Hainaut participated,” identifying the three principalities as the main suppliers of the tourneyers.Footnote 41 He is also conscious of the origin of the participants in other instances, such as the mock battle, where he specifically sums up the composition of the two armies by nationality, mentioning first the nobles from the Burgundian Circle, then the “italianos,” and finally the “españoles.”Footnote 42 For the last tournament, the skirmish in Brussels, Calvete de Estrella is even more explicit, specifying the identities of the “borgoñones,” “flamencos,” and “napolitanos.”Footnote 43 The German chronicler laid even more emphasis than Calvete de Estrella on pointing out the origins of the participating knights, distinguishing between “Niderlander,” “Burgunder,” “Spanier,” and sometimes “Italianer.”Footnote 44

The self-perception of the participating nobles also had a clear territorial slant. In the letter inviting the knights to take part in the Tournament of the Enchanted Sword in Binche, the organizers refer to themselves as “very humble and very obedient servants, the knights errant of your Belgica.”Footnote 45 Earlier in the same letter the author talks about vostre Gaule Belgique, and it is exactly this term that Calvete de Estrella translates into Latin in his account as Gallia Belgica, thus giving it far more royal, or even imperial, connotations.Footnote 46 Gallia Belgica, a geographic term used by Caesar for one of the three parts of Gaul, was used from the beginning of the sixteenth century to indicate the Low Countries, or, in a broader political context, the former kingdom of Lotharingia, including Lorraine and Franche-Comté.Footnote 47 The German account, in its turn, narrows the field to the “entire knighthood of the Low Countries.”Footnote 48 In contrast, the masquerades and festivities organized after the chivalric events offered nobles the opportunity to adopt a different identity, sometimes based on nationalities present with a typical attire (Venetians, Germans), even those with an oriental take (Albanians, Turks, or Moors).

I have identified 240 individual participants (including the judges) in the fourteen tournaments organized in the Low Countries in 1549–50 (see appendix 2). This number is already significant in itself, since it means that all these men were sufficiently trained and equipped to participate in very diverse types of tournaments. More than half the participants (124 knights) came originally from the Iberian Peninsula; these included Prince Philip, who was born in Valladolid and educated at the Castilian court. Ninety-three tourneyers can be linked to the Burgundian Circle (with Franche-Comté; these include, for example, Joachim de Rye and the brothers Thomas and Jérôme Perrenot, sons of Charles V's chancellor Nicolas); the remaining twenty-two tourneyers were from elsewhere, mostly Italy (seventeen, including Emanuele Filiberto, Ascanio Caffarello, and Vespasiano I de Gonzaga, for example, and at least four “napolitanos”Footnote 49), and some German principalities (six, including Peter Ernst I, Count of Mansfeld; Adolf, Duke of Holstein and brother to King Christian III of Denmark; and Albert, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach). Interestingly, some nobles of Netherlandish origin are viewed as Italian or Spanish by the German author, because they possessed estates and titles in these areas and/or held important (military) positions there.Footnote 50

Although numerically the Iberian participants made up the majority of the participants, they only outnumbered the other tourneyers at five of the fourteen events (see appendix 1). This means that most Iberians only participated in a few tournaments, many of them in just one, whereas their Northern counterparts frequented more events. Two nobles of Philip's household, Alonso Pimentel and Ruy Gómez de Silva, actively organized jousts (see appendix 1). What is more, as Calvete de Estrella specifically mentions, they brought their own horses.Footnote 51 Gaspar de Quiñones, who co-organized another joust in Brussels with Alonso Pimentel in May 1549, certainly thought ahead: when passing through Augsburg on his way to the Low Countries, he ordered a special harness garniture for the joust and the melee.Footnote 52 It seems that he and many other Spanish nobles knew that they had to be prepared for different mock battles in the Low Countries.

TOURNAMENTS AND THE PRINCELY HOUSEHOLD

The geographical origin of the tourneyers of course provides merely a glimpse of their social profile. For an assessment of the tournament as a vehicle of social and political integration, however, it is also important to examine their links with the princely household. This necessitated a thorough analysis of the household lists and ordinances. A relationship with the household of either Prince Philip, Charles V, or Mary of Hungary could be demonstrated for 178 of the 240 tourneyers (or 179 if Philip himself is included), thus comprising almost 75 percent (see table 2). These are minimum figures, since the sources concerning the members of the three households are not complete. An additional problem is that the names in these sources are sometimes difficult to match with names of tourneyers as mentioned by the chroniclers, not only because there are many homonyms, but also because the names are changed according to the language in which the lists were written (French, Spanish, or Latin).Footnote 53 Given that the majority of the participants were attached to one or more princely households, the general conclusion is that in the social sense the tournament had become an overwhelmingly courtly event. This constitutes a major difference from the grand tournament organized in Brussels in May 1439, where I found a link to the princely household for just seventy-three of the 235 participants—that is, approximately 31 percent.Footnote 54 This means that around the middle of the sixteenth century those involved in chivalric events had stronger links with the prince and his household than was the case in the fifteenth century.

Table 2. Number of tourneyers with an office in the household

A more detailed breakdown of the figures shows that of the 178 members of the princely households, twenty-five tourneyers were recent additions to the court, having joined these entourages only after 1550. That suggests that the tournaments may have functioned as one of the mechanisms for selecting future household officers.Footnote 55 An analysis of the three households involved demonstrates that the officers of the emperor form a clear majority, accounting for some 100 of the participants. If one includes those officers who were also members of the households of Philip and Mary of Hungary, the number rises to 112. Prince Philip's household supplied 56 officers. A striking difference is that there are many more nobles from the Burgundian Circle among the household officers of Charles (fifty-six) than of Philip (three).Footnote 56 Finally, a small but influential group of sixteen officers, all from the Burgundian Circle, belonged to the household of Mary of Hungary.Footnote 57 Their participation is particularly noticeable during the tournaments held in Binche and Mariemont, Mary's residences. Finally, only twelve tourneyers served in two or three households, so the categories overlapped only to a very small degree.

A special category among the household offices is formed by those who were members of the chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Duke Philip the Good in 1430. No fewer than sixteen participants in the 1549–50 tournaments, apart from Prince Philip himself, were members of the order. Thirteen knights, three from Castile, nine from the Burgundian Circle, were admitted to the order during the Utrecht chapter of January 1546.Footnote 58 A further nine participants would join the order at a later stage.Footnote 59 The Golden Fleece consisted of a select group of important nobles, from all the Habsburg territories and beyond, who had taken an oath of loyalty to the king, the sovereign of the order. This prestigious knightly order, “the principal embodiment of chivalry in the state,” aimed at promoting not only chivalric behavior but also cooperation among and ultimately unification of the nobility.Footnote 60 Participation in tournaments could likewise contribute to achieving these goals.

At the same time, about 25 percent of the tourneyers apparently did not have any obvious link with the household (or at least there is no relevant documentation to prove this). Even for these nobles, however, the tournaments must have served as a meeting place with the prince and his household. Calvete de Estrella specifically mentions this aspect after his enumeration of all the participants in the mock battle at Evere: “and many of them had come from their lands and lordships only to be present and receive the prince.”Footnote 61 There is evidence that the events were indeed announced to the general public and that nobles were invited to take part in them. The first tournament in Binche, for example, the foot combat in the courtyard of Mary of Hungary's palace, was proclaimed through posters attached to the gates, “one in French and the other in Spanish.” The six defenders were to be “noblemen of renown and arms” (“gentiles hombres de nombre y armas”), but the challengers could be “any adventurous knights” (“qualesquier cavalleros aventureros”).Footnote 62 The next tournament in Binche, held on August 25–26, that of the Enchanted Sword, was also said to be open to all knights who wanted to undertake knightly feats of arms. The letter, which listed the rules of the tournament, was to be made public “to all knights and nobles from the household and others . . . who want to embark on this adventure.”Footnote 63 In the German translation of the letter, the extension of the invitation to other knights outside the princely household is stressed even more firmly.Footnote 64 Indeed, the letter was already handed over to the emperor on May 5, the day of the joust on the Brussels Grote Markt, and was displayed on the entrance gate of the Coudenberg Palace so that anyone who might be interested could read it and understand the urgency to go to Binche.Footnote 65 Clearly a broader range of nobles did indeed take up the gauntlet. By participating in the tournaments they entered into active contact not only with their social superiors but also with the Habsburg princes, their entourage, and the nobilities from other parts of the Habsburg composite state.

In the years 1548–50 many opportunities arose for nobles who aspired to a position in one of the princely households. In 1548 Charles V ordered his high steward (mayordomo mayor) Fernando Álvarez de Toledo (1507–82), Duke of Alba, to set up a Burgundian household for Prince Philip, in addition to his Castilian household. The new Burgundian household was to number some 220 office holders, with the Castilian household being reduced from 240 to 100.Footnote 66 At the same time, many former Castilian officers were integrated into the new entourage. Alba made sure that several of Charles's veteran officers formed part of the new structure, but Philip could also use the new structure to put forward some of his own men.Footnote 67 During his inauguration tour, Philip was accompanied by almost his entire Burgundian household, which made this a very costly trip.Footnote 68 For the heir to the throne, the tournaments were an excellent way of gauging what each knight had to offer. Although he knew the courtiers with a Castilian background reasonably well, he had very little familiarity with his future officers from the Burgundian Circle. During and after the tournaments, both the military and the social skills of his present and future courtiers could be put to the test. The manifold collaborative melee-style tournaments may have enhanced the team-building within the household and strengthened the bond between the prince and his men. Deeds of arms on the tournament field were, moreover, a demonstration of prowess and loyalty to the prince.Footnote 69

Nevertheless, the restructuring and integration of the household was not merely a top-down operation. The nobles and courtiers employed their own strategies as well.Footnote 70 Under Philip's government, two major factions centered around two courtiers who were both present in 1549–50: Ruy Gómez de Silva and Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, who competed for domination of the king's court and hence for political power.Footnote 71 During Philip's inauguration tour they were both able to consolidate their networks of courtiers from the Iberian Peninsula and Italy and establish contacts with the nobility of the Burgundian Circle. Gómez de Silva was a Portuguese knight and a favorite of Philip's, who had been in his service as trinchante (esquire-carver) already since 1535. In 1548 he was appointed as Philip's second sumiller de corps (personal attendant in the bedchamber) and in 1553 was promoted to the first person in this capacity, which meant that he was always close to the prince; his office even granted him the honor of sleeping in the prince's chamber.Footnote 72 He had already demonstrated his chivalric skills during the tournaments of the festivities to mark the marriage of his patron Philip to Maria of Portugal in Valladolid, in November 1543.Footnote 73

At the time of the tournament cycle, however, the stronger influence was that of De Silva's future opponent, the Duke of Alba. Alba had his brother-in-law, Antonio Enríquez de Toledo, appointed as Philip's grand marshal (caballerizo mayor), for example. This high-ranking office, which Antonio maintained until his death, in 1578, meant that he would always be in the proximity of the prince.Footnote 74 Antonio participated in five tournaments in 1549–50, and was awarded the prize for the best man-at-arms in the joust organized by Ruy Gómez de Silva in Brussels on 22 February 1550.Footnote 75 The role of the Duke of Alba himself in the tournament cycle should similarly not be underestimated. He took part in four tournaments,Footnote 76 and the Italian account of the chivalric events in Binche even states that he “directed all things, intervening sometimes in one action, and then in another, here as a judge and there as a director.”Footnote 77 The German chronicler reveals that as high steward (oberster Hofmeister) Alba functioned as a gatekeeper on the occasion of the exclusive banquet presented by Mary of Hungary to the emperor, her sister Eleanor, and Prince Philip on the gallery that had been especially constructed in the moat of the Mariemont castle to view the siege.Footnote 78 In his official and ceremonial roles, Alba thereby controlled access to the princes and their households.Footnote 79

Like the Duke of Alba, there were other influential courtiers at the tournament who fulfilled the role of judge. They were mostly experienced knights and (former) jousters themselves, sometimes too old to participate actively in the tournament. Fifteen noblemen acted as a judge, twenty-five times in total, during six jousts and tournaments. Interestingly, for twelve of these twenty-five times, the judges were Iberians (see appendix 2). What is more, two Iberians, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, and Pedro Álvarez Osorio, Marquis of Astorga, and one Netherlander, Jean V de Hénin (1499–1562), Lord of Boussu, are mentioned as judge on three occasions. Two noblemen were only involved as judges and did not take up arms themselves: Francisco de Este, brother of the Duke of Ferrara, and Reinoud III van Brederode (1492–1556).Footnote 80 Most often what qualified them as judges was their high-ranking office in Charles's or Philip's household; Calvete de Estrella always mentions their rank specifically.Footnote 81 As judges they could of course favor a certain nobleman or courtier, or even assess a given participant's potential value for incorporation into the household or the army. At the same time, the judges’ task was to ensure that the fights proceeded in an orderly manner and that things did not get out of hand, so as to avoid future conflicts between individual noblemen. If a nobleman's personal reputation or honor was at stake, this could easily lead to challenges to personal combat or a duel. In 1557, for example, a duel (combat) between two participants at the 1549–50 tournaments, Richard V de Merode and Rodrigo de Benavides, took place in Mantua and was witnessed by other tourneyers, including Rodrigo's brother Juan, Alonso de Pimentel, and Francisco de Ávalos, the Marquis of Pescara.Footnote 82 While tournaments were promoted as a suitable outlet for noble violence, this type of highly personalized conflict was, by contrast, strongly condemned and prohibited by the prince.

Experienced jousters and household officers played other roles that fostered group cohesion during the tournaments. The seventy-five-year-old Claude Bouton, Lord of Corberon in the Duchy of Burgundy, merits special attention in this regard. Although his age did not allow him to participate actively, his role in the tournament cycle was manifold.Footnote 83 In 1549 he was the grand equerry of Mary of Hungary, and it is in this capacity that he, as son of an experienced literary author—his father Philippe had written Le miroir des dames (The mirror of ladies) around 1480Footnote 84—may have co-designed the tournaments in Binche and Mariemont. There he acted as judge of the foot combat on August 24,Footnote 85 but above all he played the role of Norabroc, the evil giant who was the guardian of the gloomy castle where many knights were imprisoned. He could only be beaten—and the knights liberated—by the use of an enchanted sword that was thrust into a pillar on the “Prosperous Isle,” which was guarded by three knights. The name Norabroc was a palindrome of Bouton's lordship Corberon,Footnote 86 a small village near Beaune in Burgundy, with a moated fortified castle that had been in the hands of the Bouton family since the early fifteenth century.Footnote 87 As a favorite of Charles V, in 1544 he—together with Adolf, Duke of Holstein, and Jean de Merode—was appointed guardian of the young Willem van Nassau, who in that year had inherited the principality of Orange on the death of René of Chalon.Footnote 88 It is no coincidence that it was under Bouton's supervision that the sixteen-year-old Willem made his tournament debut, besieging the castle of Norabroc together with his other guardian, the Duke of Holstein, as well as the Marquis of Pescara, and Emanuele Filiberto.Footnote 89

Two weeks later, during the foot combat in Antwerp, Willem was assisted by Pedro Felices as a padrino, a second or an aide.Footnote 90 As Juan Quijada explains in his treatise Doctrina del arte de la cavalleria, “New things are mastered through practice and perseverance . . . and under the tutelage of a good aider who knows what to do and how to explain it.”Footnote 91 Particularly during the Tournament of the Enchanted Sword, young knights such as Francisco d'Avalos, Filips van Sint-Aldegonde, and Jan IV van Glimes were assisted by more experienced ones.Footnote 92 Prince Philip was twice accompanied by a padrino: in the joust in the garden of the Coudenberg Palace, by his first sumiller de corps Antonio de Rojas, and during the tournament on horseback in Binche, by the Duke of Alba.Footnote 93 In a similar vein, during the tournament cycle in the Low Countries Juan Quijada seems to have acted as the tutor of Gabriel de la Cueva, son of Juan's patron Beltrán, Duke of Alburquerque, for whom he wrote a treatise.Footnote 94 This shows that tournaments were indeed ideal occasions for young and relatively inexperienced knights to benefit from the skills and knowledge of more veteran and expert knights of the princely household, and where bonding among the nobility could take place.

EXCHANGE, COLLABORATION, AND INTEGRATION

Gaining honor through the demonstration of combat skills and employing arms was an important motive for sixteenth-century noblemen to participate in tournaments. As the letter summoning the knights to Binche puts it, “Traditionally, knights and noblemen have been permitted to roam freely through all kingdoms, lands, and lordships to gain honor by exercising arms, exposing themselves [to risks] in search of strange adventures.”Footnote 95 At the same time, however, tournaments were closely linked to the prince and his entourage. For noblemen, princely service entailed not only fighting for the prince in his armies but also taking part in tournaments at which the prince's leadership was celebrated in various ways. This aspect is stressed in the texts that consider knighthood to be an instrument in the hands of the prince, since he is “the source of all justice.”Footnote 96 Through his active participation in ten of the fourteen feats of arms (see appendix 1), Philip presented himself as the future leader of the knighthood and the nobility of the Habsburg composite state, thereby transcending the circle of his household officers.Footnote 97 It did not suffice for a prince to possess chivalric qualities; to be the first and foremost knight and a successful leader, he also had to demonstrate these qualities on the battlefield or tournament field.Footnote 98 The participating nobles were important army leaders, so given the military challenges facing the Habsburg composite state, it was important that Philip's military leadership be firmly established.Footnote 99

Chivalric virtues were just as important for Prince Philip as they had been for his father, Charles, in February 1518, when he was inaugurated as the new king of Castile in Valladolid. There he witnessed two tournaments, both organized on the town's market square, and participated in one of them.Footnote 100 Nobles and courtiers from both the Low Countries and Castile participated in the event, and the new king himself broke three lances in four courses. He was so enthusiastic that he even wanted to participate in the melee, but various high-ranking court officers convinced him not to do so, since “it does not befit such a prince to find himself in any of these melee, and even less in those in the form of jousts where there is no order or reason and which are full of evident dangers with little profit or honor.”Footnote 101 In 1518 it was imperative for Charles that the nobles of Castile accept him as their rightful king. Through his participation in the tournament, fighting both with and against these noblemen, he clearly demonstrated that he shared chivalric values such as courage and prowess and that he was eager to show these in public.Footnote 102 As his chronicler Laurent Vital puts it, it was extremely important not only for Charles to participate in such a chivalric event but also for this news to spread over “the four parts of the world.”Footnote 103

Hence, the 1518 tournaments show striking parallels with those of 1549–50, not only in terms of the participation of the new prince in the event but also regarding the communication of his chivalric behavior to a wider audience. On the latter occasion, the nobles from different territories did indeed collaborate and vie with one another in a diverse series of combats under the military leadership of their future lord. These ranged from small-scale jousts to large melee-style events, in which the number of participants varied from 16 to 116 (see appendix 1 for an overview). This means that different combat techniques were required from the participating nobles. The fola—a collective type of combat on foot or on horseback in melee style—formed an integral part of eight of the fourteen chivalric encounters in 1549–50. The fola clearly aimed at team-building and establishing esprit de corps. In Brussels, Binche, and Antwerp, Prince Philip's team was a mixture of high-ranking nobles from Iberia and the Low Countries. All participants, including the prince, would seem to have been trained to participate in these collective combats and jousts on horseback with lances or swords. In 1540, when Philip was only thirteen years old, it was reported to Charles that, after his studies, his son liked to go hunting and correr sortija, running at the ring with a galloping horse.Footnote 104 From the biography of Luis Requesens de Zúñiga it becomes clear that Philip and other members of his household exercised every day (“ensayavanse cada día”) to prepare for the great joust on the Grote Markt in Brussels on 5 May 1549.Footnote 105 Although the display of horse-riding skills was important, both in Antwerp and Binche individual and collective foot combat was performed as well. This means that nobles were supposed to fight and defend themselves not only on horseback but also as infantrymen on foot, wielding not only the lance but also the sword, the pike, and the pollaxe.Footnote 106 After all, since time immemorial, success on the battlefield depended not only on heavy cavalry charges but also on dismounted knights fighting with a variety of weapons.Footnote 107

Another indication of the diversity of combat techniques to which the tourneyers were exposed is the inclusion of artillery and large units of mounted infantry (arcabuceros) in the two mock battles at Evere (fig. 3) and Mariemont, and at the tournament of 13 September 1549 in Antwerp (see appendix 1). Both Calvete de Estrella and Grapheus record that at this latter tournament, which was held on the Muntplein without any lists or barriers, as if it were an open field, fifty Spanish harquebusiers put an end to the jousts by firing unremittingly while skirmishing, “filling the air with fire and smoke.”Footnote 108 One would not expect this type of arms and combatants at these noble feats of arms. The resemblance with the practice of warfare is striking,Footnote 109 and the seriousness of the fighting may explain why Prince Philip did not participate in these particular tournaments.

Figure 3. Mock battle of Evere in April 1549. Ascribed to Jan Cornelisz. Vermeyen, ca. 1550, kept in the castle of Beloeil. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, nr. 10154463, cliché B187509.

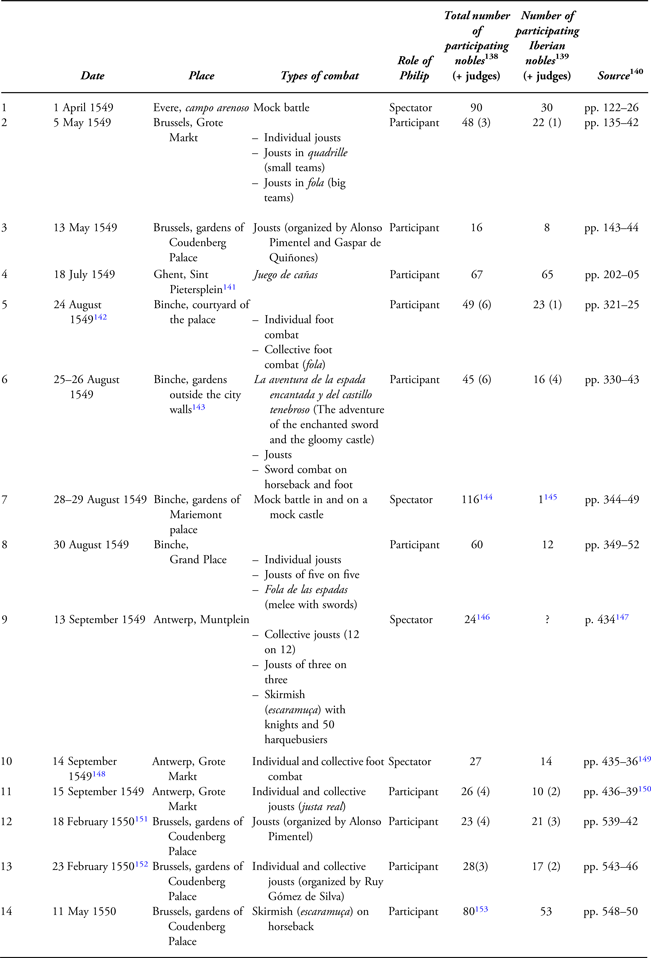

The staging of a so-called juego de cañas, or cane game (fig. 4), during the entry into Ghent on 18 July 1549 is a token of exchange of Spanish and Low Countries chivalric play. The cane game was intended to showcase the specific Iberian chivalric traditions, although the aesthetic aspects—horsemanship skills were displayed through all kinds of maneuvers—were considered more important than the purely physical ones. Instead of heavy armor, participants used reed spears “with a weighted lower part, usually filled with sand, that could be thrown fairly harmlessly at the feigned enemy, and daggers carried in the left hand.” Participants were dressed as moors and rode with a Moorish saddle.Footnote 110 Calvete de Estrella stresses that for both the town-dwellers and “all the knights of those states” this was something totally new that they “do not practice and so seldom see.”Footnote 111 Indeed, only two non-Iberian nobles, Lamoraal van Egmond and Emanuele Filiberto, the future Duke of Savoy and a cousin of Prince Philip,Footnote 112 participated in the 1549 Ghent juego, but it is highly significant that sixty-five Iberian knights were given an opportunity to show off their skills. Prince Philip also participated in this juego in Ghent, demonstrating his horsemanship, learned in Spain, to the Netherlandish audience. What is more, Philip and his courtiers must have brought their special outfits and equipment with them from Spain to the Low Countries to be able to partake in this particular performance. Earlier that year, at Epiphany, a cane game was organized in the courtyard of the ducal palace in Milan. Of the forty Iberian noble participants, thirty-three took part in the chivalric events in the Low Countries, and twenty-eight of them were present in the Ghent cane game.Footnote 113

Figure 4. Juego de cañas in Valladolid, on the occasion of Philip the Handsome's visit to Castile. Unknown artist, first half of the sixteenth century. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, nr. 1015445, cliché B184488.

Interestingly, in response to a formal wish of Prince Philip, the town administration of Ghent had also prepared a bull run after the game of canes; this combination was common in Iberian joyous entries, but rarely occurred outside the Iberian Peninsula. The games were intended for different audiences, the bull run considered more as “popular entertainment,” whereas the cane game appealed more to nobles and courtiers.Footnote 114 In the end the bull run did not take place, according to Álvarez because “the bulls were so tame that the boys could even play with their tails.”Footnote 115 The financial records of the town, however, show that the treasurer and the grand bailiff, who had spent five to six weeks purchasing bulls in the surrounding parishes, sustained a financial loss since the “bulls had suffered injuries caused by the Spanish.”Footnote 116

Although the cane game was perhaps specifically planned for and by Iberian nobles, most other events were designed to enhance participation of nobles from diverse backgrounds. To this end, for five events (appendix 1, nos. 2, 5, 6, 12, and 13) regulations were described and published on posters, one even proclaimed by a king of arms.Footnote 117 In all these five events the principal organizers are described as mantenedores—that is, persons who maintain or hold the lists against any challengers, called aventureros.Footnote 118 The challengers could engage in a combat by touching the shield of one of the mantenedores or touching the plume worn by a certain lady.Footnote 119 Most of the regulations were concerned with the way the combats were to be conducted—e.g., how many courses the combatants would run and the conditions for obtaining a prize, which could entail the number of lances broken, but also having the most gallant appearance or simply being the best jouster.Footnote 120 These regulations not only helped to create a level playing field for knights familiar with different jousting traditions and to avoid accidents in the lists, but also to encourage the participants to do their best to obtain prizes and honor. Indeed, the prize ceremonies served to distinguish individual knights who could act as examples for the rest. Many competitors passed on their prizes, which included jewels, vessels, cups, necklaces, medals, and golden bracelets, to the ladies present at the concluding banquets, masquerades, and dances. Hence the knights could show their liberality and underline the fact that these events were specifically intended as a “servicio de sus damas” (“service to the ladies”).Footnote 121

The guidelines that were made public for these events are very similar to the so-called chapters of arms, which regulated many fifteenth-century feats of arms.Footnote 122 One specific regulated chivalric event was the pas d'armes, a tournament, sometimes involving theatrical production, in which a knight or a group of knights defended either a passage (such as a bridge or a gate) or a symbolic object (such as a fountain or a column) against all challengers.Footnote 123 The first of these highly ritualized tournaments were organized in Castile in 1428 and 1434.Footnote 124 However, they became most popular in the Burgundian lands, possibly through intensive chivalric contacts with the Spanish realms, where between 1443 and 1470 no fewer than nine pas d'armes were organized. Two events in 1549–50 (appendix 1, nos. 6 and 12) stand out for their theatricality and fictional scenario and show resemblances with some of the late medieval pas d'armes. The tournament in Binche in August 1549 had a proper name referring to this scenario: La aventura de la espada encantada y del castillo tenebroso (The adventure of the enchanted sword and the gloomy castle). The event was elaborately crafted with several different automata (self-operating machines), and knights playing characters taken from popular medieval Arthurian romances and more recent Iberian ones such as Amadís de Gaula (Amadis of Gaul, first printed in 1508).Footnote 125 This appealed to a common chivalric culture shared by nobles from different parts of Europe. At the same time, the role played by Prince Philip in the Tournament of the Enchanted Sword was crucial: as Beltenebros, he was the only knight capable of withdrawing the sword and liberating the knights imprisoned by Norabroc in the gloomy castle. The story portrayed the heir to the crown as a deliverer to whom the imprisoned knights immediately paid homage. As Roy Strong points out, “the political aims were clearly to present Prince Philip as the preordained ruler of the Low Countries.”Footnote 126 Emily Peters, forgetting the Iberian roots of the pas d'armes, even maintains that after establishing his own Burgundian household, with its proper rules and practices, Philip was firmly embedded in the Burgundian tradition of chivalric display.Footnote 127

The Shrovetide joust organized by Alonso Pimentel in February 1550 was another event with clear theatrical aspects, albeit with fewer political ambitions than the Binche one. Pimentel presented himself as “the Aggrieved Knight” (cavallero aggraviado), entering the jousting field of the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels in full armor, dressed in black velvet, and with a black cart drawn by four white horses on which was seated a naked blindfolded figure representing Cupid, the God of love, and an executioner with the figure (figura) of Fortune hanging by her feet from a gallows. Since Cupid had supposedly been unfavorable to Pimentel, the joust was undertaken to take revenge: for every course Pimentel won, Cupid would be seated one step higher on a staircase of nineteen steps leading eventually to the noose. During the masquerade after the tournament, Cupid was resuscitated by the gods, and he immediately shot an arrow at Lady Florence de la Thieuloye, “for whom the feast was celebrated.”Footnote 128 Baden Frieder suggests that the theme of this particular joust was inspired by the fact that the members of Philip's household “were preparing to take their leave of lovers they had met in the Low Countries.”Footnote 129 This would suggest that there was a great deal of interaction between the noblemen and noble ladies present at the tournaments and the festivities organized afterward during nine out of the fourteen events. Indeed, dances and masquerades were closely connected to the tournament and are even considered as a continuation of the competition in the lists, although they were of course more a peaceful way for nobles to meet and greet.Footnote 130 Despite the fact that, since at least the twelfth century, love for an (often inaccessible) lady was deemed a proper justification for knights to participate in tournaments, even becoming a topos in romances describing these chivalric events, this noble motive could disguise more worldly ambitions, such as gaining the trust of a prince in the hope of eventual social promotion.Footnote 131

Yet, did all these chivalric encounters also lead to more long-lasting relationships between nobles from different geographical backgrounds? According to David Crouch, from the very start weddings and tournaments were closely related social events during which “networks of relationships were formed, secured or broken, and the aristocratic identity of both individuals and the social elite [was] itself confirmed.”Footnote 132 Marital exchanges were efficient tools for nobles to confirm and preferably enhance their social status and possessions. One of the tournaments in 1549, the event staged on the Muntplein in Antwerp on September 13, was organized on the occasion of the wedding between Thomas Perrenot and Helena of Brederode, lady-in-waiting of Mary of Hungary. According to Calvete de Estrella, this alliance between the children of two high-ranking courtiers (Nicolas Perrenot, Lord of Granvelle, and Reinoud III, Lord of Brederode, Charles V's chancellor and chamberlain, respectively) was arranged during the feasts of Binche.Footnote 133 Whatever the truth of Calvete's statement, it is evident that post-tournament celebrations offered multiple opportunities for establishing alliances.Footnote 134

This is confirmed by another alliance involving tourneyers concluded earlier that year: on January 23, Margaretha van Egmond, sister of Lamoraal, entered into marriage with Nicolas of Lorraine, Count of Vaudémont.Footnote 135 The marriage was solemnized in the chapel of the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels, in the presence of the emperor, his sisters Eleanor and Mary, and numerous high-ranking courtiers and nobles who were accompanied by their wives. It was immediately preceded by “a foot combat in service of the ladies” (“ung combat à pied pour le service des dames”) in the courtyard, organized by Hernando de la Cerda, Alonso de Aragón, Alonso Pimentel, and Emanuele Filiberto, Prince of Piedmont.Footnote 136 All of these knights were active participants in the tournament cycle later that year, as were the prizewinners and judges present at that combat on foot, which was fought with swords and pikes. The three-day festivities included banquets, dances, and masquerades, perfect occasions for intermingling and socializing among nobles from different parts of the Habsburg Empire. This tournament thus shows that the cycle of 1549–50 did not come out of the blue, and that there was already interaction on (and outside) the tournament field before the arrival of Prince Philip.

These two marriages between nobles from Holland and Franche-Comté attest to the integration of the nobility within the Burgundian Circle. However, there was never a deliberate policy by the Habsburg princes to foster the formation of a mixed supraterritorial nobility. There are only three examples of marriages between noblemen from the Low Countries and noble women from the Iberian Peninsula, all concluded before the advent of Prince Philip, in 1549. At the same time, the nobilities in the North and the South had their own matrimonial strategies, and finding a partner from outside their own well-known social and geographical scope was simply not part of the game.Footnote 137

CONCLUSION

The expansion of the Burgundian, and subsequently the Habsburg, composite state made it imperative to cultivate bonds between the prince and his household, on the one hand, and among the nobles of different principalities and kingdoms, on the other. Tournaments offered an ideal martial and social environment for this. Although certainly not lacking in theatrical and courtly elements, tournaments were serious military exercises. In particular, the concentration of the flower of chivalry of the Habsburg composite state in Binche, near the border with the kingdom of France, should be seen as a demonstration of military power. The diversity of types of combat, with fighting both on foot and on horseback, the range of weapons used, and the inclusion of artillery units all show that nobles possessed important martial skills. These were not only exhibited directly to a courtly and urban audience but also, via the extensive coverage of the tournaments by diverse chroniclers writing in different languages, to a broader public throughout Europe. Prince Philip could thereby present himself as the head of his new household, which underwent important changes in these years; as chief of the knighthood; and, last but not least, as the future leader of the Habsburg composite state. He was carefully embedded in the chivalric traditions of the diverse parts of the Habsburg composite state that converged, apparently smoothly, in the major towns of the Low Countries, situated in Brabant, Flanders, and Hainaut.

Both the chroniclers and the tourneyers were aware of the different geographical backgrounds of the participants in the events, which reflected the heterogeneous character of the Habsburg composite state. Yet, despite their diverse origins, they spoke a common chivalric language, and the events formed an ideal opportunity for nobles to demonstrate their prowess before an audience and to forge links as brothers-in-arms. The tourneyers were not exclusively, but certainly predominantly, attached to one or more princely households. Moreover, leading members of the household played a crucial role in staging the events and helping other high-ranking but younger, less established, nobles with what for some of them must have been one of their first performances in the lists. In that sense, the tournaments served as a regulated outlet for noble violence, controlled by the prince and his closest collaborators. Furthermore, integration was pursued not only within the lists but also during the banquets and dances accompanying the tournaments. In this way, these chivalric encounters both created and cemented the bonds of knightly brotherhood within the entourage of the household, while at the same time reaching out to others who did not (yet) belong to the new prince's circle.

APPENDIX 1 Overview of jousts and tournaments organized in the Low Countries in 1549–50

APPENDIX 2 List of participants and judges in the chivalric encounters organized in the Low Countries in 1549–50