INTRODUCTION

Though the Jews and Christians of early modern Italy had much to disagree about, the existence of hell was broadly a matter of consensus. Scholars and theologians of both religions believed that sinners would receive their just deserts in an infernal afterlife, often envisioning it as a subterranean realm of fiery tortures. Both faiths consigned some sinners to damnation and others to temporary purgation, and both faiths expended no small efforts to discussing the dimensions and demarcations of this underworld, whether it be in Scholastic treatises of theology, kabbalistic homilies, or imaginative poems.Footnote 1 The contours and imagery of inferno and purgatory of Western Christianity, on the one hand, and the gehinnom of Judaism, on the other, are extremely similar, distinguished mostly by small theological contentions and the identities and religious affiliations of the souls consigned to torture in the hereafter.

Though the significance and extent of it are debated, there is little doubt that the Jews of early modern Italy interacted with and participated in the culture and literature of their Christian neighbors. They were native speakers of Italian dialects and thus could easily converse with Christians. Moreover, they could read texts in Latin and Italian, even quoting these in their own works written in Hebrew. Inasmuch as the issue of hell is concerned, however, quotations of Christian texts or ideas are scarce. Theological and mythical discussions of hell in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by kabbalists such as Menahem Azaria da Fano (1548–1620) and his student Aaron Berachia da Modena (d. 1639) leave little to no impression of the Christian discussions of the issue from the period.Footnote 2 Likewise, the various poetic portrayals of hell (and the afterlife in general), from the medieval Immanuel of Rome (ca. 1261–1335) to the seventeenth-century Moses Zacuto (ca. 1625–97), seem intent on omitting any mention of or allusion to the literary achievements of Dante.Footnote 3 On the surface, the marked presence of hell in the culture and discourse of early modern Italy—be it the Scholastic commentaries on Dante's Commedia, the Catholic interest in providing precise measurements, descriptions, and quantifications of hell, or the Reformation controversy regarding purgatory's existence—furnished little material for Jewish discussions of the very same topic. Though signs of influence may be discerned, rarely does one find this manifesting as explicit acknowledgment.

This general silence seems to be borne less of ignorance and more of intentional acts of omission. While the Jewish literature of the period is often in dialogue with Christian texts, such dialogue did not always take place explicitly. Italian Jewry was a minority culture, desperately seeking to assert its cultural superiority over an often hostile Christian majority, and the use of non-Jewish sources could prove to be a delicate issue, with missteps occasionally provoking internal censure or protest.Footnote 4 Moreover, certain ideas, concepts, and texts were more congenial to Jewish adoption than others. It is, after all, one thing to imitate or draw inspiration from a Christian portrayal of hell; it is something else altogether to quote one, implicitly conferring upon its writer the status of an auctor.Footnote 5 If one accepts Robert Bonfil's contention that Jews in Renaissance Italy engaged with the contents of Christian culture inasmuch as they “could be considered neutral” and “perceived as different from, or better yet, opposed to Christian identity,” one may perhaps understand the general reluctance to acknowledge non-Jewish discussions of hell which were naturally colored by the deeply theological concerns of the Christian religion.Footnote 6

Nevertheless, isolated islands of acknowledgment do crop out of this sea of silence. The evidence is admittedly scarce, but the fact remains that at least some Jewish writers, seeking to better understand the nature of hell and wishing to shed light on the ancient Jewish texts that described it, did gaze across the religious divide. The present article is dedicated to an exploration of three instances of this phenomenon—explicit attempts to interpret gehinnom in light of Christian hell and purgatory.

The purpose of the present study is threefold: 1) to explicate new sources for the study of the cultural history of Italian Jewry in the early modern era; 2) to offer one of the few studies of Jewish beliefs about hell in the early modern period; and 3) to probe the contexts and conditions that made explicit acknowledgment, and more importantly appropriation, of Christian notions about hell possible. What precisely motivated the individuals discussed in this article to quote Christian texts about hell? Why do they feel comfortable importing the Christian structure of hell into their theological discussions while other theological aspects of Christianity are happily ignored? What kinds of texts do they quote? And why do they write about these subjects in the specific contexts they do? The answers to these questions can better shed important light on how hell was envisioned by Jewish writers and thinkers living in Counter-Reformation Italy as well as help illuminate the dynamics of Jewish culture in early modern Italy and the way Jewish scholars navigated the use of Christian beliefs and sources in their own writings and thought.

HELL AND ITS REALMS IN THE JEWISH TRADITION

Jewish literature, from antiquity to the early modern era, has had much to say about the nature, function, and makeup of gehinnom. While it was rare to find an entire book dedicated to the subject, hell crops up in several central Jewish texts. The Talmud, kabbalistic works, ethical literature, and medieval theological tracts all had something to say about hell, ranging from the briefest of mentions to lengthy schematic mappings or detailed theological discussions. Many works containing discussions of gehinnom had been printed by the sixteenth century and were thus widely accessible, furnishing scholars and laypeople alike with a rich and diverse literature about the infernal. To name just two examples: the Zohar, the near-canonical text of Kabbalah—printed in two competing editions in the mid-sixteenth century—is peppered with dozens of mythical descriptions of hell as well as several exhaustive lists of hell's various compartments.Footnote 7 Likewise, Moses Nachmanides's (ca. 1194–1270) Sha‘ar ha-Gemul—a theological work about the immortality of the soul and the nature of divine reward and punishments, printed three times in the sixteenth centuryFootnote 8—includes a dedicated section on the nature and theology of hell.Footnote 9

A full account of the development of gehinnom in the Jewish tradition is certainly beyond the scope of this study; nevertheless, a cursory overview of the trends arising from a wide range of sources may prove a helpful backdrop for appreciating the unique rapprochement between Jewish and Christian beliefs that these sources seek to effect.Footnote 10 In particular, it will be shown that many Jewish sources treated hell as a specific and real location and also commonly divided it into distinct parts, each dedicated to a different degree of punishment—trends that ran parallel to those taking place in Christian theology during the same period.

Already in antiquity, rabbinic texts treated gehinnom as a physical locum.Footnote 11 Though some traditions place hell on another plane of existence,Footnote 12 in most cases it is incorporated seamlessly into the cosmography of the world.Footnote 13 It is described as a massive subterranean chamber (often quantified with precise measurements) filled with fire, ice, and other tortures.Footnote 14 Moreover, it can be physically entered not just through death but via material terrestrial openings.Footnote 15 To be sure, there have been many attempts in Jewish history to allegorize such physical descriptions. In the Middle Ages, philosophers with more rationalistic tendencies were loath to take seriously the notion of gehinnom as a real location, preferring to cast the mythology of hell as an elaborate allegory.Footnote 16 That being said, several medieval writers—Saadia Gaon (882–942), Nachmanides, and Hasdai Crescas (1340–1411), to name just a few prominent examples—explicitly emphasize that gehinnom is a distinct and concrete realm.Footnote 17 Besides abstract discussions of hell from antiquity to the Middle Ages and into the early modern era, one finds mythical, poetic, and cosmographical attempts to describe hell in vivid detail—reinforcing the notion of gehinnom as a material reality.Footnote 18 Such descriptions are especially prevalent and colorful in the Zohar, as mentioned above.

Gehinnom was, however, rarely treated as a single undifferentiated location, and there is a long history of dividing it into distinct madorim—literally, “dwelling places” for the deceased. Such demarcations are evident already in antiquity. The number seven has been an enduring commonplace—likely an attempt at creating symmetry with the number of heavens in talmudic lore. These seven chambers are often given names based on synonyms for the underworld appearing in the Bible and other sources. The precise list varies from source to source, but one famous version from the Talmud reads as follows: “[1] Netherworld [She'ol], [2] Destruction [Avadon], [3] Pit of destruction [Be'er Shaḥat], [4] Tumultuous Pit [Bor Sha'on], [5] Miry Clay [Tit ha-Yavan], [6] Shadow of Death [Tzalmavet], and [7] the Underworld [Eretz Taḥtit].”Footnote 19 An account cited by Nachmanides supplements the seven madorim with an eighth: the absolute nadir of hell, referred to as arqa (Aramaic for “earth”).Footnote 20 In other accounts, arqa is understood as the general name of that realm that contains the seven components of hell.Footnote 21

Besides distinct chambers, Jewish sources also broach the issue of different gradations of punishment in gehinnom—including the distinction between those subjected to temporary purgation and those eternally damned. In one influential talmudic text, the schools of Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel debate as to which types of sinners are eternally damned and which must simply undergo purgation for several months.Footnote 22 In this early text, all of the punishments seem to take place in a single, undifferentiated location—gehinnom; naturally, however, some texts sought to coordinate the notion of distinct gradations of punishment for different degrees of sin with the stratified structure of hell itself. Thus, the Midrash Psalms notes that “behold! there are seven habitations for the righteous and seven habitations for the wicked—for the wicked according to their works and for the righteous according to their works.”Footnote 23 Likewise, in one passage of the Zohar, a detailed list is provided that assigns distinct categories of sinners to different realms of hell (e.g., “the fifth compartment is called Sheol. Judged there: Heretics, informers, those who reject the Torah, and those who deny the resurrection of the dead”).Footnote 24 Elsewhere in the Zohar, however, a more binary division is evident, with special focus being placed on two of hell's seven chambers: avadon and she'ol. The former, it is argued, is a place of eternal destruction and damnation; the latter is a place of temporary suffering and eventual salvation.Footnote 25

Though there is far more to say on this issue, it should be evident that Jewish discussions and ideas about hell mirror at least some of the elements of Christian discussions taking place during the same centuries. Whether due to their shared sources or due to cases of cross-fertilization, members of both faiths were wont to envision hell as a concrete subterranean underworld and to speculate as to the gradations of punishment taking place within it.Footnote 26 Likewise, Jewish sources, like Western Christianity in the High Middle Ages, ended up dividing the infernal underworld into distinct realms—though, in the case of the former, far greater emphasis was placed on the function of the two realms of purgatory and hell.Footnote 27 But these similarities aside, there is no doubt that the tendency of Christianity toward dogmatic formulations distinguishes it from Judaism in this respect. As is the case with many theological issues, Jewish discussions remained flexible and diverse. Thus, divergent approaches, descriptions, and attempts to allegorize hell were allowed to propagate mostly unhindered, no final word ever being issued and no major controversies ever arising.Footnote 28 Needless to say, this contrasts sharply with the position adopted by the Latin Church, in which the precise nature of the afterlife became an important and even substantive tenet of faith.

Arguably, it is precisely this lack of systematization in the Jewish tradition that may have tempted three Jewish writers in Cinquecento Italy to turn to the more systematic approaches of their Christian neighbors. Two annotators and one author incorporated the more concrete doctrines of Christianity into their own attempts to understand Jewish descriptions of hell, as will be explained presently.

INFERNO AND PURGATORY IN THE MARGINALIA OF MENAHEM DA RAVENNA

Handwritten marginalia in printed books are an invaluable resource for the study of Jewish beliefs in early modern Italy, not only providing new information about the beliefs and scholarship of well-known individuals but also bringing to light entirely new figures who would otherwise be lost to history. Menahem Immanuel ibn Hanamel da Ravenna is one such figure. His only formal literary legacy was a short legal query.Footnote 29 He compensates, however, for this sparse literary activity with truly voluminous marginalia appended to the margins of his printed books. The present study is the first scholarly treatment of this figure.

The efforts of cataloguers and my own archival work have located six printed books owned and annotated by Ravenna. Three of the books are kabbalistic tracts (Menahem Recanati, Ta‘amei ha-Mitzvot [Constantinople, 1544], Zohar [Cremona, 1558], Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut [Mantua, 1558]). The other three are a Hebrew manual of sample contracts (Le-Khol Ḥefetz [Venice, 1552]), an incunable copy of Joseph Albo's philosophical work Sefer ha-Iqarim (Soncino, 1485), and, finally, Sebastian Münster's Aramaic-Latin dictionary (Dictionarium Chaldaicum [Basel, 1527]). Identification is based on Ravenna's ownership inscription appearing on the title pages of four out of the six books. The other two books (Zohar and Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut) lack title pages but can be definitively identified on the basis of handwriting and annotation style.

Ravenna's writings reveal next to nothing about his personal life. The aforementioned legal query demonstrates that he maintained correspondence with two fairly prominent sixteenth-century figures: Jewish legalist Moses Provencal (1503–76) as well as the kabbalist Mordekhai Dato (1525–ca. 1590), both active in Northern Italy (and Mantua more specifically). In Ravenna's notes, one finds two non-Jewish interlocutors quoted by name: a Spanish diplomat named Mateo and an Italian canon, Marco Marini, who will be discussed below. Ravenna's style of handwriting and extensive use of Italian in his otherwise Hebrew notes leave no doubt that he, like most of his interlocutors, was also a Jewish Italian. Though he primarily cross-references Hebrew books in his marginalia, he does quote several books in Latin and Italian; he almost exclusively references printed books (as opposed to manuscripts). He mentions the burning of the Talmud in Rome (1553) and the Gregorian Calendar Reform (1582), and he only quotes books printed before 1593, placing his activities in the second half of the sixteenth century.

As mentioned, one of the books owned by Ravenna was a copy of Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut—an uncharacteristically organized and methodical discourse on kabbalistic theology originally penned, it seems, in Barcelona in the early fourteenth century.Footnote 30 In this volume, the main work is dwarfed by the voluminous commentary appearing alongside it, the work of fifteenth-century Spanish émigré and kabbalist Judah Hayyat. Hayyat, who was commissioned to write a commentary of the work, was less than fond of the author's kabbalistic doctrine and dedicated the majority of his commentary to lengthy digressions and attempts to subvert the author's views. Among other things, he sought to champion the mythical, theosophical approach that had prevailed in his former homeland of Castile—an approach that was encapsulated in the Zohar but had yet to gain significant traction in Italy.Footnote 31

Toward the book's end is a very short discussion of the fate of righteous gentiles in the world to come.Footnote 32 Arguing with the author of Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut, and citing proof from earlier kabbalistic sources, Hayyat avers that gentiles—no matter how righteous—simply cannot enter the garden of Eden (i.e., paradise) and must descend into gehinnom.Footnote 33 There is, however, some profit to the righteous gentiles’ efforts. If wicked gentiles must bear the full brunt of hell and its tortures, righteous gentiles are allowed to reside not in the deepest fathoms of gehinnom but in its uppermost layer. Hayyat, who seems to view the garden of Eden and gehinnom as existing on another plane of existence, posits that the two realms lie one atop the other, with a thin diaphanous barrier separating the realm of punishment from the realm of reward (“for nothing but a hairsbreadth separates the garden of Eden from gehinnom”). The righteous gentiles are thus able, from their elevated position in gehinnom, to derive an iota of pleasure from the light of paradise, even if they are barred from actually entering it. Hayyat—who was expelled with his coreligionists from Spain and underwent great hardships during his arduous journey to Italy—concludes emphatically: “God forbid they should be in the garden of Eden! For no man with a foreskin shall benefit from it!”Footnote 34

This is all the fifteenth-century Hayyat has to say on the matter, and though he lived his entire life in Christian countries he saw no need to draw any parallels to analogous Christian discussions of the issue. This is not at all surprising. Besides a somewhat understandable antipathy to Christianity, evinced here by his theological position, Hayyat, as mentioned, subscribed to the mythical Castilian form of Kabbalah; as a result, he eschewed elaborations of Kabbalah based on non-Jewish sources, be they philosophical or theological.Footnote 35

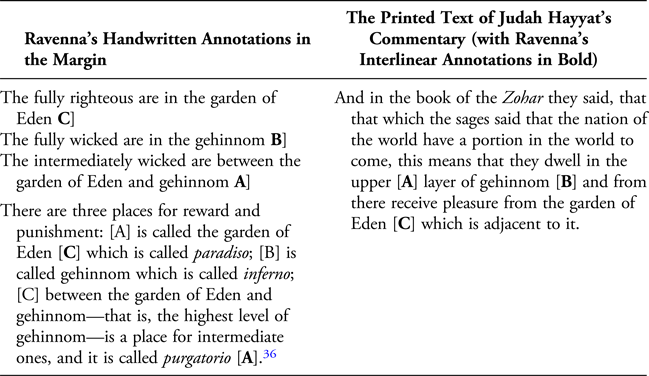

Menahem da Ravenna, writing just a century after Hayyat, was different in this respect; he was willing to bestow theological mercy on the gentiles as well as draw from their sources in order to do so. To this end, Ravenna offers an interpretation of Hayyat's description, effectively subverting its anti-gentile message. Below is a translation that preserves the mise-en-page of the source text:

The note has been added to the immediate left of the printed text of Hayyat's commentary. The Hebrew letters used to label the three realms in the note are duplicated with signe-de-renvoi in the main text, matching each realm of the afterlife with each of the realms described by Hayyat. If one takes Ravenna seriously and applies the implications of what he is saying to Hayyat's statement, he seems to be taking pity on the righteous gentiles whom Hayyat so emphatically condemned to hell. If the righteous gentiles are in purgatory, this implies that their tortures are fixed in duration; they may yet emerge from the underworld and ascend to paradise. Interestingly, Hayyat conflates a three-tiered system of reward and punishment (righteous, wicked, and intermediate) with Hayyat's ethnic and ethical division between Jew, righteous gentile, and wicked gentile.

More important, however, than the exact fate of righteous gentiles is the fact that Ravenna has unabashedly adopted a thoroughly Catholic, tripartite division of the afterlife.Footnote 37 This division of hell would have been all too familiar to a Jew living in Italy in the aftermath of the Council of Trent, during which bishops were enjoined to “diligently endeavour that the sound doctrine concerning purgatory . . . be believed, maintained, taught, and every where proclaimed by the faithful of Christ.”Footnote 38 But though Ravenna uses Catholic vocabulary and conceptions, he buttresses this demarcation with thoroughly Jewish prooftexts. Thus, on the top of the very same page, Ravenna quotes a text from the Zohar. This passage was referenced above, but it is worth quoting in full, as it represents one of the most explicit cases of a Jewish text mirroring the Western-Christian binary between purgatory and hell:

In gehinnom there are chambers upon chambers, two, three, up to seven . . . and whosoever contaminates himself with [his evil ways], when he arrives at that place, he descends to gehinnom and he descends to the lowest chamber. For there are two chambers next to each other: she'ol and avadon. He who descends to she'ol is judged there and he receives his punishment and they raise him up to another higher chamber. And [he continues to rise], stage after stage until they raise him up [entirely]. But one who descends to avadon is never raised up.Footnote 39

The division here between eternal damnation and temporary purgation is indeed explicitly delineated in this zoharic passage; the congruity with the binary division between purgatory and hell is almost too precise to ignore.Footnote 40 Nevertheless, Ravenna's choice to focus on this passage, among several sources within the Zohar and elsewhere, is in and of itself telling. Ravenna could easily have discussed the seven chambers of gehinnom with not two but seven gradations of punishment. He had ample sources for doing so (as discussed in the previous section). Instead, he focuses on a passage that corresponds to a simpler binary division between hell and purgatory, essentially reinforcing the Western Christian position on the issue.

In addition to these notes, Ravenna provides important information as to the particular circumstances that gave rise to his syncretic approach. Glued to the aforementioned page of Ma‘arekhet ha-Elohut is a loose note in Ravenna's handwriting. At its top are written instructions to insert the note at the relevant page. Part of the note is illegible, but what can be made out reads as follows: “from Don Marco Marino a canon of St. Antonio de Vienna [i.e., a member of the congregation of Saint Anthony] in Padua [and he asked me in the year] 1578: in how many places does the soul receive reward and punishment? [and I answere]d him that they are three.”Footnote 41 Ravenna goes on to explain that he responded to Marino's question by quoting the aforementioned zoharic passage and defining the biblical words avadon and she'ol as inferno and purgatorio, respectively. Marini, who seems to have discussed the issue with Ravenna in person, “copied [this zoharic passage] and went on his way.”Footnote 42 Ravenna adds that he later learned that Marini had incorporated this discussion into his own book.

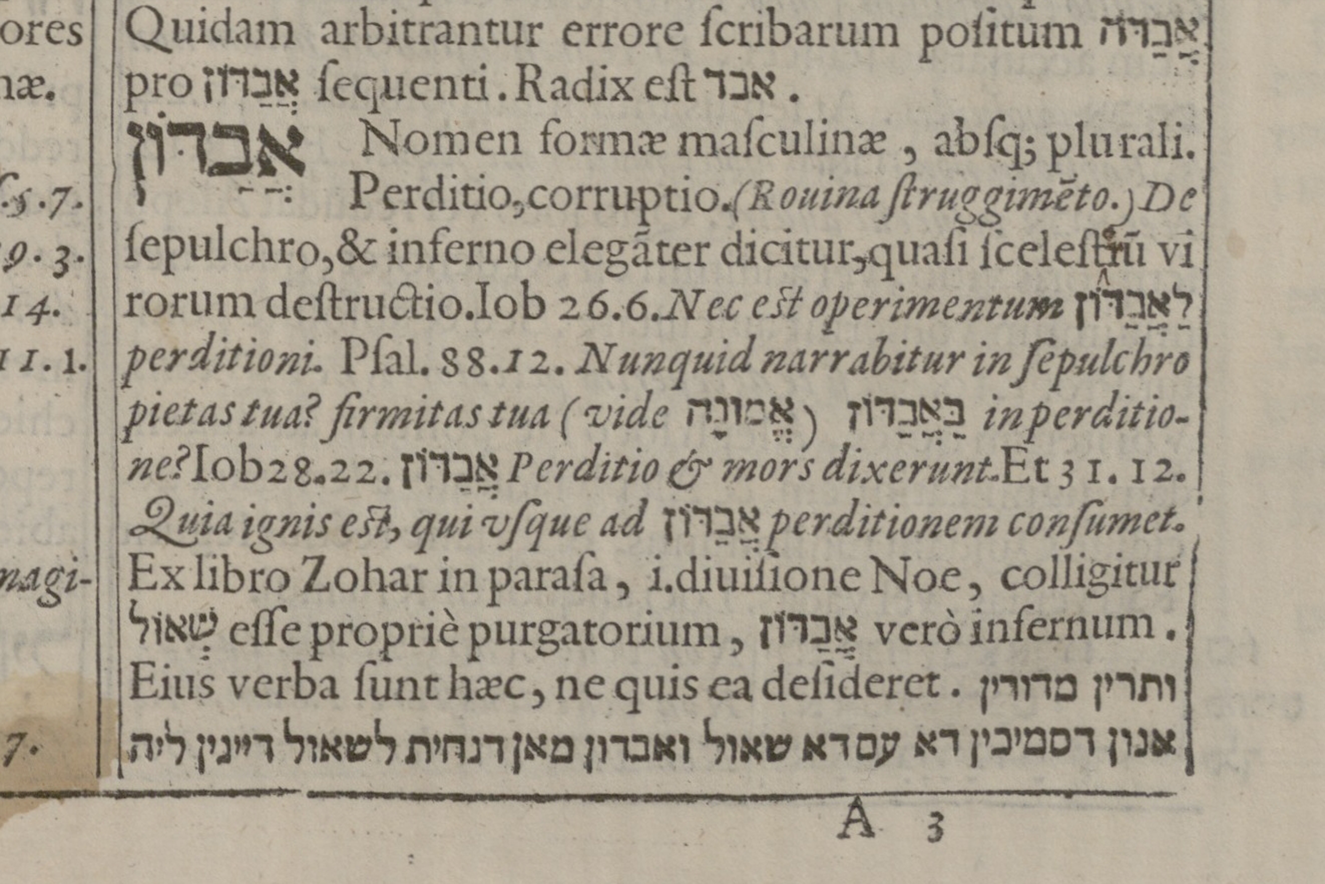

The canon with whom Ravenna discussed hell was no obscure figure. Marco Marini (1542–94) was a linguist and translator of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic; over the course of his life, he served the pope as a censor of Hebrew books and the Venetian state as secretary of correspondences with the Middle East. His most famous work by far is Arca Noe (or in Hebrew, Tevat Noah [Venice, 1593]), an extensive lexicon and concordance of Biblical Hebrew.Footnote 43 In his publication of this book, Marini enlisted the help of several Jewish figures: Leon de Modena, Samuel Archivolti, and Israel Zifroni all contributed short poems and commendations in Hebrew to the book's paratextual materials. It seems that Marini, like many Hebraists, also enlisted the help of Jewish interpreters in his attempts to understand the more obscure words of the Bible—in this case, turning to Menahem da Ravenna to help him understand the meanings of the biblical words for the underworld, avadon and she'ol. Marini evidently found Ravenna's citation of the Zohar compelling—and indeed, he does include the zoharic passages and Ravenna's explanation in his Arca Noe in the relevant entries for these biblical terms (see fig. 1). Notably, his debt to his Jewish interlocutor is never acknowledged.

Figure 1. Marco Marini's definition of the biblical word avadon. Courtesy of the National Library of Israel.

It seems, then, that Ravenna's turn to Christian conceptions of hell was tied not only to his passive knowledge of Catholic beliefs but also by his active engagement in dialogue with a Christian canon.

DANTE IN THE MARGINALIA OF RABBI EZRA DA FANO

If Ravenna refers only to theological commonplaces without citing any particular texts, his contemporary Rabbi Ezra da Fano (ca. 1530–1608) penned a pair of notes that explicitly reference not just the concept of hell but a Christian portrayal of it. Ezra da Fano was an Italian rabbi and kabbalist who lived in Mantua and Venice intermittently.Footnote 44 He took part in the communal politics of his day, published important Jewish classics, and instructed prominent Jewish figures in Kabbalah. He was also a prolific scribe who copied dozens of manuscripts, many of them kabbalistic. Like Ravenna, he wrote almost nothing original of his own but did append often extensive marginalia to the manuscript books he copied and the printed books he purchased.

Five printed books with Ezra da Fano's annotations have been identified—four of them kabbalistic. The most impressive by far is a set of the Mantua edition of Sefer ha-Zohar (Mantua, 1558–60) bound in six volumes, four of which are housed in the Schocken Library in Jerusalem.Footnote 45 The large uncut margins of these quarto volumes boast a wide range of notes from both Fano himself as well as subsequent generations of Mantuan readers and writers. Fano's notes, written just a few years after printing, explain the text, mark passages as interesting, and add emendations from manuscripts and other printed editions. Occasionally, to elucidate the more cryptic passages of the Zohar, Fano quoted midrashic and kabbalistic books, in both print and manuscript. Though he generally restricts himself to Jewish sources in his notes, very rarely he does reference Christian translations or interpretations of the Bible, without offering further specification. Indeed, among all of his notes, there are only two instances of unambiguous references to non-Jewish figures, which will be discussed presently.Footnote 46

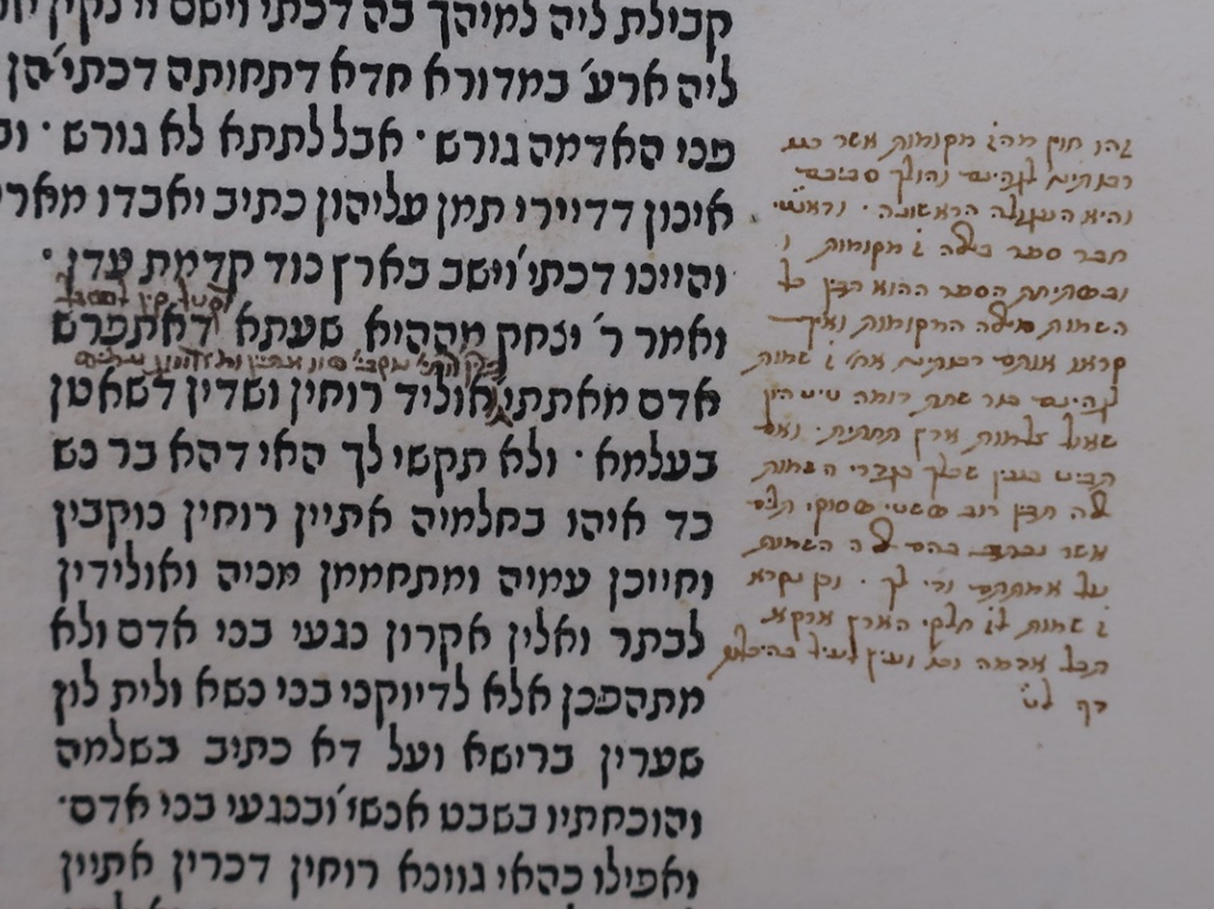

The first note in question appears alongside a zoharic elaboration of the biblical story of Cain's murder of his brother Abel and his subsequent exile.Footnote 47 The passage speculates as to Cain's ultimate fate, concluding that the biblical murderer (or perhaps his soul?) was interred underground in a realm called arqa. It will be recalled that the name arqa was associated with hell in different Jewish texts, being designated either as the eighth and lowest of hell's chambers or as the name for the location of hell itself. Regardless, the passage suggests that Cain was damned to arqa for all eternity.

Fano, writing a note in the margin, ponders as to the precise position of arqa vis-à-vis the other chambers of gehinnom listed in traditional Jewish sources. To this end, he envisions hell as a series of concentric circles—each circle representing one of the seven names of hell. In this scheme, arqa constitutes the eighth outer circle: “[arqa] is besides the seven places by which our rabbis called gehinnom and it goes around them and it is the first circle.”Footnote 48 This seems to accord with the position of Seder Rabba de-Bereishit (in contradistinction to that of Nachmanides) which designates arqa as the locum that contains the seven chambers of hell; Fano envisions this containment in terms of concentricity.

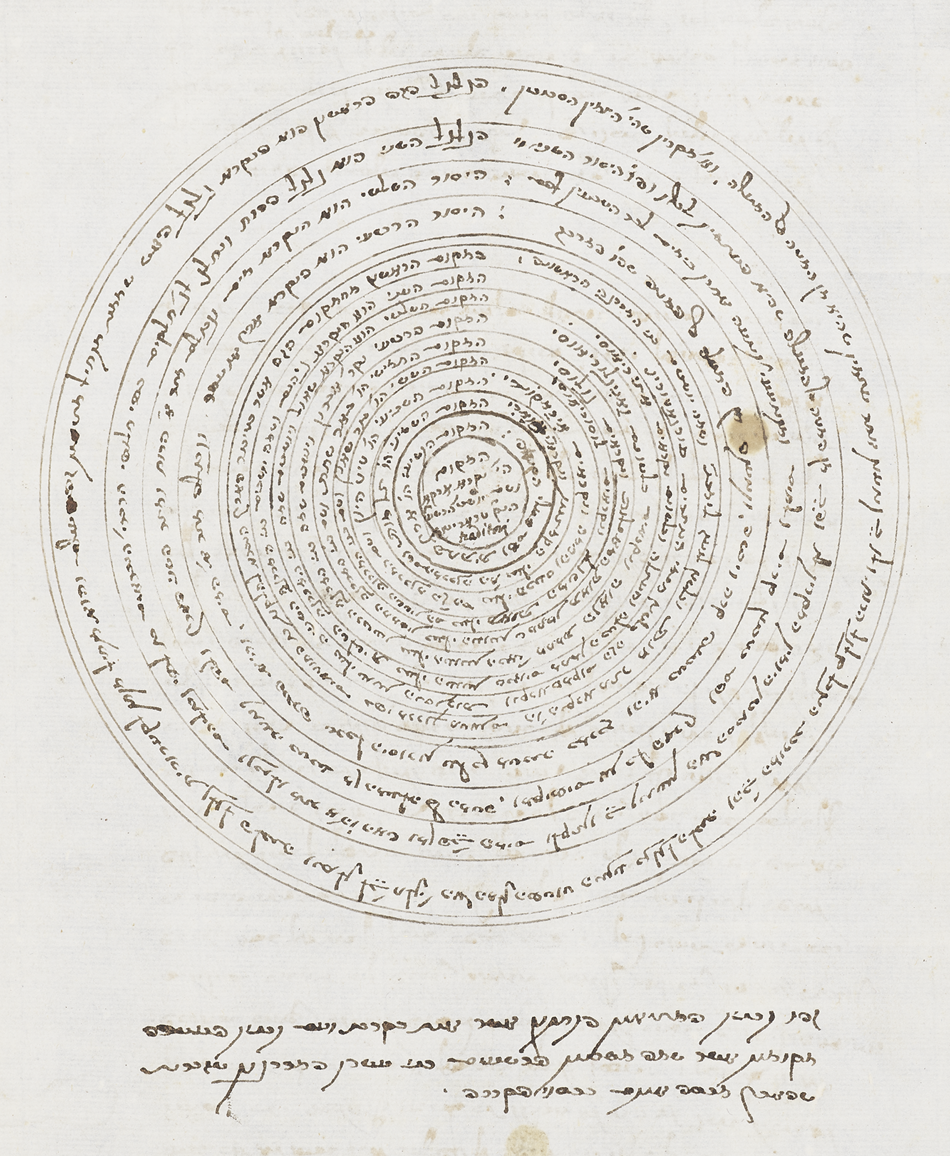

Arqa has been named by this zoharic text. But what are the names of the other seven chambers of hell? Fano offers two possibilities. The first is a non-Jewish source: “And Dante composed a book about these seven places and in the introduction to that book you will understand [the] names of those chambers.”Footnote 49 The second is a Jewish source: Fano mentions what rabbinic sources have to say on the matter, “and our rabbis stated that gehinnom has seven names Bor, Shaḥat, Dumah, Tit ha-Yavan, She'ol, Tzalmavet, and Eretz Taḥtit.”Footnote 50 The seven realms of hell can thus be categorized either according to the sins enumerated by Dante or according to the infernal synonyms listed in rabbinic texts and stemming from the Bible (see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Ezra da Fano's first marginal note about Dante. Courtesy of the Schocken Institute in Jerusalem.

Fano's continued interest in Dante is evident just a few pages later: there he appends a very similar note to another zoharic discussion of hell. It is the very same zoharic passage broached by Ravenna, which distinguishes between two major chambers of hell—avadon, the realm of the damned, and she'ol, the realm of souls who must undergo purgation. But unlike Ravenna, who focused on the distinction between purgation and damnation, Fano is far more interested in the general fact that both the Zohar and Dante divide hell into distinct chambers. In this instance, Fano is more precise as to which part of Dante's work he is referring: “And see Dante in the Purgatorio. And at the beginning of the introduction to the commentary of that book, you will find the parts of terrestrial gehinnom [corresponding to] the seven parts of the world,Footnote 51 and likewise gehinnom has seven parts” (see fig. 3).Footnote 52 Here, in other words, Fano not only cites Dante but aligns the seven parts of gehinnom with the equivalent realms in the Divina Commedia. These seven realms are identified, it seems, not with the circles of inferno but with the terraces of purgatory. In this instance, Fano does not even bother to quote rabbinic literature, and simply mentions Dante as a source for dividing gehinnom into separate realms.

Figure 3. Ezra da Fano's second marginal note about Dante. Fano's note marked with a square. Courtesy of the Schocken Institute in Jerusalem.

Dante was no exception to the general Jewish reluctance to quote Christian discussions about hell in their writings during this period. The sanguine approach of some twentieth-century historians of Italian Jewry—producing statements such as “Dante was widely quoted by Italian rabbis of the Renaissance”—is simply not borne out by the evidence.Footnote 53 Although some important Italian Jewish figures did read and reference Dante, explicit mentions of him are not abundant.Footnote 54 As suggested before, reticence about a popular non-Jewish source need not necessarily be attributed to a lack of interest. In the case of Dante, at least some Jews did indeed own his books and read his works.Footnote 55 But though Dante may have been read, it may not have always been culturally acceptable to quote him in the context of religious writing. Fano is, in other words, an outlier.

Fano, it seems, is doing more than drawing a comparison between Jewish visions of hell and Christian ones. Indeed, he seems to be identifying the two accounts, and perhaps even modeling Jewish texts after Dante's description. The choice to portray hell as concentric circles is not unknown in Jewish sources, but it is quite rare.Footnote 56 That Fano envisions hell as eight concentric circles—arqa being the outer circle, encompassing seven circles from the rabbinic list—may suggest that Dantean notions of hell's geometric structure served as a model (though, admittedly, both may simply have drawn from the common imagery of the celestial spheres). That being said, it is unclear the extent to which the Italian kabbalist is trying to incorporate the entirety of Dante's vision into his zoharic readings. Does Fano acknowledge the distinction between the Inferno and Purgatorio? Or perhaps he only adopts the Purgatorio (which he explicitly quotes) but rejects the Inferno as a Christian invention? The notes, being extremely laconic, leave much to the imagination, and it is hard to reach any definitive conclusions. Regardless of these details, the very use of a literary text to discuss zoharic cosmography is notable. Fano does not seem to be treating Dante as mere allegory—a bella menzogna—but as a factual description of the afterlife, equivalent to the Zohar's own sober attempts at cosmography, an approach very much at odds with the way the Commedia was traditionally understood during the period.Footnote 57 Could it be that Fano, unconcerned about whether or not Dante's Commedia constituted heresy—and cognizant of the parallels between Dante's multidimensional vision of the afterlife and traditional Jewish beliefs and visions—was able to take the poem's “ubiquitous truth claims”Footnote 58 more seriously than his Christian contemporaries?

Shedding some light on the way Fano approaches the Commedia is the issue of the precise bibliographical medium in which he accessed it. For, indeed, if one takes Fano at face value, he is not quoting Dante at all. In both notes, Fano references an introduction—in the first note, “the introduction to that book,” and in the second, “at the beginning of the introduction of the commentary of that book.” As Dante wrote no introductions or commentaries, it follows that Fano is not, in fact, quoting the words of the Florentine poet himself, but rather those of his later interpreters. Prose introductions to the Commedia were a prominent feature of its fifteenth- and sixteenth-century editions. Fano may, for instance, be referring to Christoforo Landino's commentary edition, which indeed begins with a succinct summary of the “Sito, forma, et misura dell'inferno.”Footnote 59 Alternatively, he may refer to the commentary of Alessandro Vellutello and specifically to the “descrittione” that the humanist commentator adds as a preface to each of the three parts of the Commedia. Notably, Vellutello's “descrittione dell'inferno” includes striking woodcuts of each realm of hell with their respective titles, which may very well have left an impression on a casual reader such as Fano.Footnote 60

Whatever the case, Fano's focus on a commentator's introductions suggests a more complex relationship with the work than simply that of a traditional reader. Rather, Fano may have been a so-called non-reader. “Sustained by paratextual information such as covers, titles, editions, woodcuts and other illustrations that accompany the text,” he may have known of Dante and known something about his works, but not necessarily have read the Commedia cover to cover.Footnote 61 Indeed, if Fano wished to understand the structure of hell without poring over lines of terza rima, the prose introductions by Landino and Vellutello would have been invaluable tools. This being the case, any attempt to understand Fano's notes as offering precise alignments between the Zohar and the Commedia might be beside the point; Fano may have had only a passing knowledge of Dante that he casually applied in his notes. The point is not the details but the general insight that a prominent Christian poet described worlds already anticipated by the Zohar itself.

THE INFERNAL COSMOGRAPHY OF ABRAHAM YAGEL

Ravenna and Fano confined their literary efforts to informal notes in the margins of their printed books; by contrast, their contemporary Abraham dei Gallichi Yagel (1553–ca. 1623) was a prolific writer and literatus who made a habit of adapting and translating Christian materials for his works. Though a doctor by profession, Yagel had wide-ranging interests in science, philosophy, astronomy, astrology, magic, and Kabbalah. Among his works published in his lifetime are Moshi‘a Ḥosim (a tract about treating the plague), Leqaḥ Tov (a simplified Hebrew guide to Jewish faith, modeled after Casinius's Catholic catechism), and Eshet Ḥayil (a commentary on the “woman of valor” passage in Proverbs 31).Footnote 62 Published only in the twentieth century was his Gei Ḥizayon: an account of a heavenly journey taken with his father, in which he discusses philosophical and scientific issues with the souls of the deceased.Footnote 63 He also penned two large encyclopedic works dedicated, among other things, to astronomy, cosmography, Kabbalah, magic, and science—Be'er Sheva and Beit Ya‘ar ha-Levanon, which both remain in manuscript to this day. David Ruderman's study of Abraham Yagel's life and works has highlighted the overarching vision that guided Yagel's efforts: his was a world dominated by parallelism, unity, and interconnectedness. He sought to point not only to the parallels between different layers of reality but also to the threads that united both the Jewish and non-Jewish sciences.Footnote 64 That Yagel would seek to harmonize the Jewish and non-Jewish visions of hell ought then not to come as a surprise.

Yagel addresses the issue of hell and its nature in two contexts within his writings. The first, discussed at length by David Ruderman, appears in Beit Ya‘ar ha-Levanon as part of a kabbalistic discussion about the possibility of animal transmigration (the notion that human sinners may be punished via reincarnation into the bodies of animals). Yagel expounds upon the idea by making recourse to traditional kabbalistic sources. In passing, however, he suggests that transmigration—a doctrine that the Church regarded as particularly odious—may parallel the Christian notion of purgatory. In doing so, Yagel subtly defended the Jewish notion of transmigration from Catholic objections; transmigration, so he argued, was not altogether different from Catholic notions of the soul's purgation after death.Footnote 65

However, a very different presentation of purgatory, and hell more generally, appears in Yagel's other encyclopedic work, Be'er Sheva.Footnote 66 In this work, preserved in a single autograph copy, hell and purgatory are discussed cosmographically—not as symbols for such subtle processes as reincarnation, but as a series of concrete, subterranean chambers.Footnote 67 The discussion is part of Yagel's broader effort in Be'er Sheva to offer a comprehensive depiction of the cosmos and the earth. Having described the ten celestial spheres and the four elemental spheres, he reaches the earth, and from there plumbs the depths of hell itself. Yagel's depiction of terrestrial hell is a fascinating and unprecedented blend of Jewish and Christian traditions about the afterlife, and besides some passing comments by Ruderman it has yet to be studied thoroughly.Footnote 68 For my purposes, it mirrors the descriptions of Ravenna and Fano, and represents yet another attempt to seriously and explicitly incorporate Christian descriptions of the underworld into a reading of Jewish texts and an understanding of the world more generally.

Yagel begins by framing his discussion of hell as a matter of consensus between Jewish and non-Jewish scholars (“it is a tradition among our sages and is also agreed upon by the Christian scholars”).Footnote 69 He then discusses the entrances of hell as described in the Talmud, and broaches the nature of hell's fire. After these preliminaries, he proceeds to describe hell's structure, positing a ten-fold division:

The sages saw that it was good to divide this place . . . according to gradations of wickedness, one atop the other. And based on our sages of blessed memory . . . as well as the [teachings] of the wise men of the [gentile] nations, we see that [hell] is divided into ten chambers, with innumerable subchambers.Footnote 70

Yagel bases this number on general parallelism with the other layers of reality (the godhead, the heavens, and the earth) as well as on the existence of ten categories of sin, each of which requires its own punishment in its own dedicated realm. To demonstrate this latter point, Yagel launches into a long excursus about the ten categories of sin. The sins are listed in order of increasing wickedness. The first two categories are completely rooted in Jewish legal principles: unintentional sins “from which even a righteous man cannot be saved” and sins in which the sinner is not certain that he has indeed sinned (for which he would, in the Temple period, be required to bring a conditional guilt offering). The next seven categories of sin are based on ethical considerations: sloth, pride, gluttony, lust, wrath, greed, and envy (in that order). The final category of sin represents the actions of a thoroughly wicked man, who is not compelled by base desire but rather sins willfully, actively defying his creator.

It is clear that the bulk of Yagel's framework is dominated by the seven capital or deadly sins of Christian ethics—an appropriation not unprecedented in the Jewish tradition, but certainly not common. While many Jewish polemicists objected to the usefulness of such a categorization, the model was adopted favorably by at least one fifteenth-century Provençal scholar, Isaac Nathan of Arles.Footnote 71 Ravenna also adopts the concept in one of his marginal notes.Footnote 72 Yagel, for his part, prominently includes the seven sins in his Hebrew catechism, Leqaḥ Tov:

Teacher: What are the seven [types of] abomination within the soul?

Student: They are the seven capital categories of sin, from which all sins derive. And [as] they seem trivial, a man may not be careful [to avoid them]. But if he is seduced by them, they drive him from the world.Footnote 73

Interestingly, neither in his catechism nor in his discussion of hell does Yagel explicitly acknowledge the Christian origins of this concept. Instead, he claims that the idea derives from the Jewish tradition, pointing to a talmudic passage that discusses the seven different names of the “evil inclination.” In his discussion of hell, Yagel expends no small effort to match the order of the capital sins he has listed to the order of names of the evil inclination as they appear in the Talmud; likewise, each sin is matched with a distinct biblical figure. Lust, for instance, is aligned with Solomon, who, according to the Talmud, called the evil inclination an enemy (based on Proverbs 25:21: “If your enemy is hungry, give him bread to eat”). Yagel provides the following explanation: Solomon, infamous for his attraction to foreign women, was well acquainted with the sin of lust; he referred to lust as an enemy (or more literally, one who hates) precisely because those who are lustful, having presumably slept with their neighbors' wives, inspire hatred in all those around them. This method of aligning different lists and categories is a hallmark of Yagel's discussion of hell in particular and his imaginative homiletical efforts to bridge the gap between Jewish and non-Jewish sources more generally.

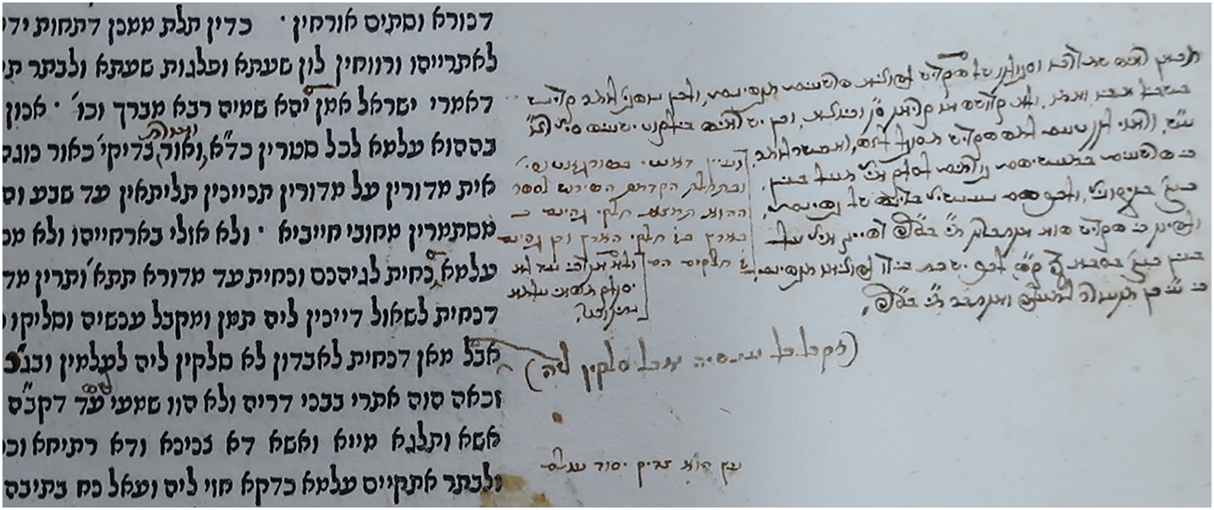

Having laid the groundwork with his list of the ten types of sin, Yagel proceeds to explain how hell is structured in correspondence to each one of these categories. Not content to simply align chambers with sins, Yagel also aligns each chamber with one of the celestial spheres. Moreover, two of the chambers are aligned with specific realms discussed in Christian theology, and seven are aligned with the classic seven names of hell in rabbinic tradition. In this context, Yagel draws heavily on a particular mythical Jewish description of hell—included, among other places, in Nachmanides's work about the afterlife, Sha‘ar ha-Gemul—that notes the location of prominent biblical and rabbinic sinners in each realm. Thus, in characteristic fashion, Yagel creates a symmetry between the different layers of his cosmographic scheme while also effecting a rapprochement between divergent Jewish and Christian descriptions of the afterlife.

Yagel identifies the first two realms of hell with limbo and purgatorio, respectively. The comparison is notable, but largely semantic. While one cannot really expect Yagel to include the notion of limbo as a place for the unbaptized in his scheme, it is interesting that purgatory is also stripped of its Christian overtones. For Yagel, purgatory is simply one chamber of gehinnom among many. Because it is the second chamber, it offers some of the least severe punishments for one of the shortest amounts of time, but it is otherwise not fundamentally different from the next seven chambers, which also dole out punishment for a limited duration. The next seven layers—those corresponding to the seven deadly sins—are made to correspond to the classic rabbinic schema of seven layers of gehinnom, as shown above. Finally, the last chamber of gehinnom is referred to as arqa. This last chamber, reserved for those who rebel against God, is indeed a place of eternal damnation, unlike the other nine.

An example will demonstrate how Yagel seeks to tie these divergent threads together. According to Yagel, the eighth chamber of hell is dedicated to greed (or as Yagel translates it, qamtzanut—i.e., miserliness). This corresponds to the eighth sphere (from above to below)—that of Venus. Venus is associated with women, who, Yagel informs us, are known misers. Likewise, the realm's Hebrew name is Tzalmavet (the sixth out of the seven names of hell in one prominent rabbinic list), literally “shadow of death.” This alludes to the punishment given to misers: they are shrouded in darkness, a fitting punishment for those so myopic as to think their piles of money would avail them in the hereafter. Finally, the biblical villain who is condemned to Tzalmavet (according to the text quoted by Nachmanides) is King Ahab, who had Naboth executed in order to take possession of his vineyard. The sin of greed is thus used as an organizational principle to explain the realm's rabbinic name, the identity of its residents, and its astrological correspondence.

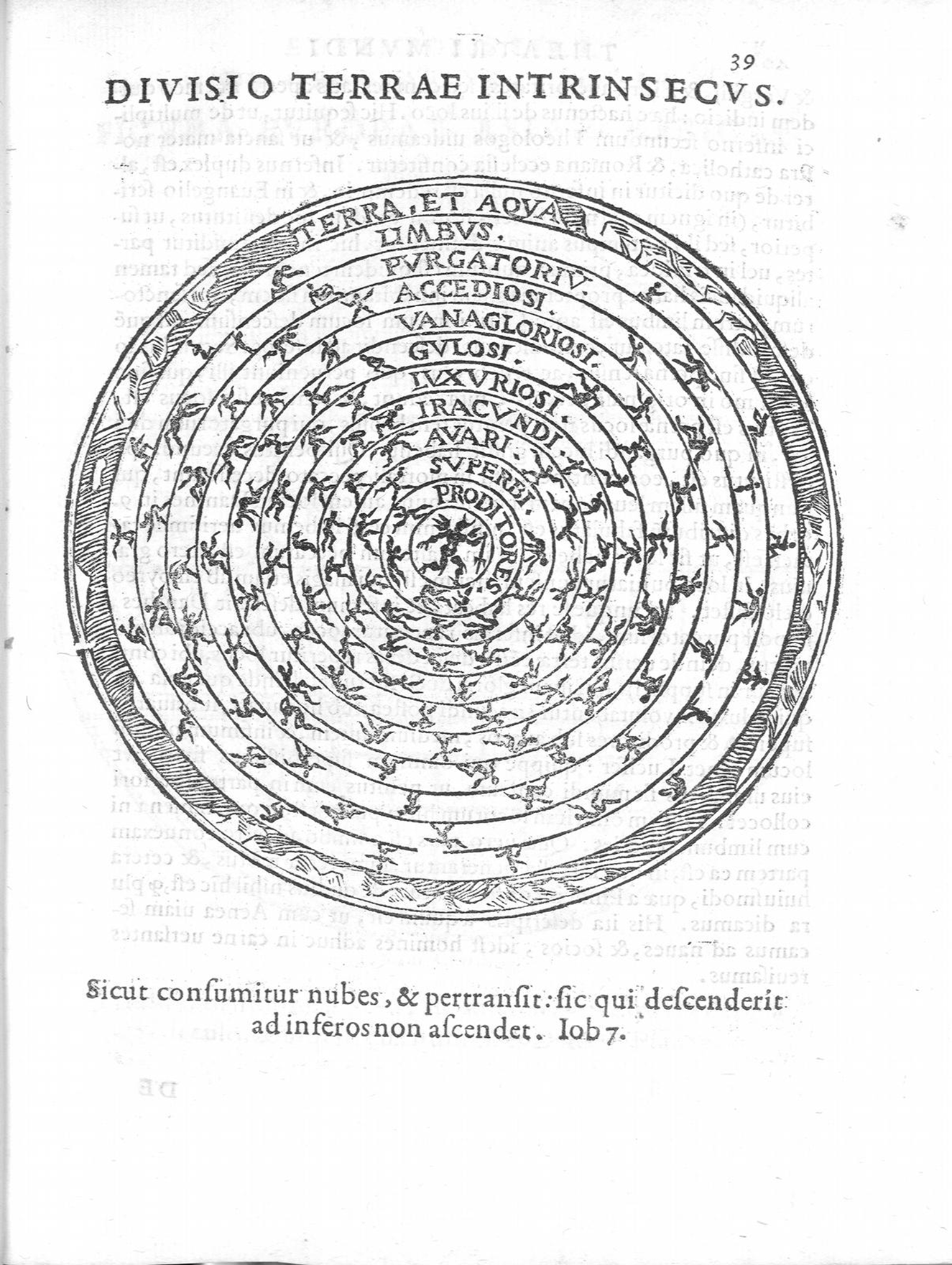

Yagel concludes his exposition of the celestial spheres and hell by drawing two diagrams. Here the chambers of hell are drawn not as vertical but as concentric circles, corresponding in structure to the heavenly spheres, evoking the imagery alluded to in Ezra da Fano's note, and by extension the imagery of Dante himself. While Yagel restricted himself to Hebrew in his verbal exposition of hell, here he uses Italian (inscribed in Hebrew or Latin letters) to name the sins of each realm of the underworld (see fig. 4).

Figure 4. Abraham Yagel's diagram of the elemental spheres and the circles of hell. Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Reggio 11, fol. 33v.

A LATIN SOURCE FOR YAGEL'S DEPICTION OF HELL

The details of Yagel's scheme do not seem to correspond to the prominent literary or theological mappings of hell that prevailed in the period, Christian or Jewish. The use of the number ten is particularly notable. Ten is never used in any Jewish sources with which I am familiar as a scheme for delineating hell—seven or eight being the preferred count. Likewise, in Christian theological texts, a relatively simple four-fold scheme is preferred (limbo, bosom of Abraham, purgatory, and hell).Footnote 74 Indeed, the portrayal closest to Yagel's is that of Dante in the Commedia, as suggested by Yagel's use of the seven sins. That being said, Yagel departs from Dante in several important respects: the total number of circles, the order of the sins, and, most important, his choice to include purgatory as a circle within hell as opposed to a terrestrial mountain separate from it. All of these represent significant departures from Dante.

The relative uniqueness of Yagel's depiction of hell and its ambiguous relationship with Dante's schema can be explained by his sources. Though Yagel fully acknowledges his indebtedness to non-Jewish texts and even uses Christian terminology and concepts, he never names a single source explicitly. Luckily, his marked fidelity to his sources proves enlightening: Yagel did not borrow his depiction of hell directly from Dante but rather from a particular astronomical and cosmographical work: the Theatrum mundi et temporis (Venice, 1588) of Giovanni Paolo Gallucci (1538–ca. 1621).

Though he was a prominent publisher, little of Gallucci's biography is known. Born in Salo, he would later move to Venice, where he was one of the founders of the second Venetian academy and served as a tutor to the children of the nobility.Footnote 75 It was there, in 1588, that he would print his most popular work, Theatrum mundi et temporis, which would go on to be reprinted six more times (thrice in Spanish translation). Richly illustrated, and adorned with several volvelles, the work offers an overview of the terrestrial and especially celestial worlds. Gallucci presents the work as an accessible alternative to more complex ways of visualizing the universe; stripped of lengthy demonstrations, it offers novices and scholars alike a visual representation of the heavens and the earth.Footnote 76

Gallucci did not, however, restrict himself to the observable world. Between a discussion of lunar eclipses and maps of the continents, the cosmographer turned to another issue: the infernal worlds lying beneath the earth's surface. He declines to offer demonstrations for the fact of hell's existence—Scripture and faith are more than enough evidence, he avers—but does present some arguments for locating the realm of eternal punishment under the surface of the earth. He then proceeds to list the realms of the underworld, beginning with limbo, moving on to purgatory, and concluding with infernus. Here he notes that Dante divides this realm into nine orbs, corresponding to nine types of sin. “And though we cannot be certain that this is the case,” Gallucci notes, “it seems to be true.” After all, “if one sin is graver than another, it is fitting that it be punished in a place more distant from the Empyrean heaven.”Footnote 77 Thus, whether or not Dante is to be taken at his word, his scheme is, at the very least, theologically sound. The list of chambers dedicated to sins follows this order: Accediosi, Vanagloriosi, Gulosi, Luxuriosi, Iracundi, Avari, Superbi (the slothful, vain, gluttonous, lustful, wrathful, greedy, proud). Accompanying Galluci's verbal description is an illustration of the underworld comprising ten circles: purgatory, limbo, and then a chamber for each of the seven sins and an innermost chamber for the Proditores (betrayers or traitors). In the illustration, each of the circles of hell is populated by stylized human shapes, gesticulating in what can only be presumed to be agony. In the innermost circle flutters a winged devil bearing a downturned pitchfork. Beneath the illustration appears a quotation from Job: “As a cloud is consumed, and passeth away: so he that shall go down to hell shall not come up” (see fig. 5).

Figure 5. Giovanni Paolo Gallucci, Theatrum mundi et temporis (Venice, 1588), fol. 39r.

Though he explicitly cites Dante, Gallucci has strangely departed from the Commedia: not only has he reordered the circles of the Inferno—perhaps based on his own assessment of the severity of the sins in question—but he has also subsumed purgatory within the underworld. Moreover, arriving at the number nine for the nine circles of hell, but including purgatory instead of limbo to complete this number, is very much at odds with the Commedia. It is beyond the scope of this study to speculate as to the motivations or sources that led Gallucci to thus adapt Dante's vision. Suffice it to say that Gallucci is not presenting a familiar Dante.

Yagel's verbal presentation of the ten circles of hell—as well as his diagram—is identical to that of Gallucci. Moreover, his arguments for placing hell underground, as well as the justification for different chambers for different sinners, seem to paraphrase the explanations offered by Gallucci. To name just one example, Gallucci, arguing that inferno and purgatory must be underground, offers the following argument: “[Given that] good [men] and evil [men] are most distant from each other, and [given that] no place is more distant from the Empyrean Heaven than the center of the earth . . . therefore [it follows that] the center of the earth, and the places around it, are the places of wicked men.”Footnote 78 Abraham Yagel follows suit and writes as follows: “And the Christian sages said that since the wicked and righteous are two diametrically opposed opposites, it is fitting, in accordance with divine justice, that their punishments be diametrically opposed [as well]. And just like the soul of the righteous man ascends to God . . . above, so too it is fitting that the soul of the wicked man should descend below. And the lowest point of all existence is the center [of the earth]. Therefore, gehinnom must be at the center of the earth.”Footnote 79 This explains why Yagel bothered to include limbo and purgatory in his scheme without adapting their theological content. They are simply elements of a diagram that he has faithfully copied. Yagel's innovation, then, is not to map the contours of hell from scratch, but to appropriate an existing map and paint it in Jewish colors.

A more detailed study of Be'er Sheva would reveal the extent to which the work as a whole is based on paraphrasing and borrowing the cosmographies of non-Jewish sources. Gallucci may have been just one source among many, or, alternatively, may have furnished some of the astronomical and geographical material in Yagel's work—not just the description of hell. Regardless, the adoption of Gallucci's scheme of hell accords well with Yagel's general efforts to point to the parallelisms that unite all layers of reality. A hell of four or seven layers would not have fit well into Yagel's scheme. A hell of ten layers, however, corresponds to the ten spheres, the ten sefirot of the godhead, and the ten parts of the world. Gallucci's model conveniently provided such a schema. If Yagel had doubts as to the authority of the somewhat playful vision of a specific Christian astronomer, he could convince himself with his own homiletical acrobatics. The ten circles, in Yagel's mind at least, made sense and corresponded well with the teachings of Judaism, the writings of Christian astronomers, and the repeatable nature of the cosmos.

CONCLUSION

The cases of Menahem da Ravenna, Ezra da Fano, and Abraham Yagel offer important insights into the way a Jewish audience perceived Christian views of hell, and how these views were neutral enough to be incorporated into the study of Jewish texts. I argue that Jewish writers borrowed their visions of hell from lived experience as well as from Christian texts that framed hell not as a matter of faith but as a matter of concrete reality; furthermore, their descriptions of hell may have also had polemical motives, since comparison could help them assert the superiority of the Jewish religion over its Christian competitor.

Ravenna differs from Fano and Yagel in that he never quotes a textual source for his ideas about hell. Indeed, he presents the existence of purgatorio and inferno as part of a common view of the world, considered obvious to him and everyone around him. That Ravenna was writing in Catholic Italy shortly after the Council of Trent, as mentioned above, would only have reinforced his familiarity with this particular view of the afterlife. To be sure, Ravenna's relationship with Marco Marini may also have contributed to this perception. His conversations or correspondence with the Christian canon may have accustomed him to discussing certain issues using a Christian idiom. Nevertheless, the fact that Ravenna quotes no Christian texts and no Christian sources, only Jewish ones, seems to indicate that it is precisely because he regarded the existence of purgatory and hell as commonplace, neutral knowledge that he felt comfortable superimposing them on a Jewish textual discussion. Had Ravenna drawn these ideas from a reading of a theological text instead of his acquaintance with popular ideas, perhaps he would have been more reluctant to draw comparisons.

Fano and Yagel are arguably also dealing with a neutral notion of hell. Though, unlike Ravenna, they quote or paraphrase specific texts in their treatment of hell, the sources they have picked are telling. That Fano's conception of Dante is filtered through the commentary tradition is important. The commentaries of Landino and Vellutello, like many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century readings of Dante, take Dante's wor(l)ds very seriously. They do not just visualize Dante's hell; they mathematize it, offering exact measurements of its chambers and debating the precise size of the Devil or the specific location of inferno's entrance. Such discussions conferred upon the work an aura of cosmographical reality that somewhat removed it from the particularistic sphere of the Christian religion. This framing of Dante's Commedia in terms of “infernal cartography”Footnote 80 may have been precisely what allowed Fano to draw comparisons between the Zohar's descriptions of hell and those of the Italian poet.Footnote 81 Hell presented not as classical or Christian allegory, but as neutral cosmography, could be more easily digested by a Jewish religious scholar. Yagel's turn to Gallucci's description of hell may represent a similar move. Though Gallucci does not hide the religious overtones of his description, he does nevertheless incorporate his description into a book of cosmography and astrology. Like Vellutello and Landino to Dante, Gallucci frames Catholic beliefs about the afterlife as part of a scientifically neutral discourse; hell framed not as theology but as part of a general description of the cosmos would have allowed Yagel to more easily accept it into his work.

These points notwithstanding, it is worth considering what precisely a comparison between Jewish and non-Jewish sources is ultimately meant to accomplish—or to put it differently, who benefits, culturally speaking, from drawing a comparison between Christian and Jewish notions of hell? Ravenna, Fano, and Yagel all present Jewish gehinnom in expressly Christian colors. All three of them, however, argue that these colors arise from a faithful reading of ancient Jewish texts—be they texts that are truly ancient (such as the Talmud) or texts believed to be ancient (such as the pseudo-epigraphical Zohar). Ultimately, this kind of cultural maneuvering undermines the Christian claims to exclusivity and suggests that anything reasonable said by Catholic theologians or Christian cosmographers had already been anticipated in Jewish texts. While this kind of thinking is precisely the type of strategy used by Christian Hebraists to strengthen the theological claims of Christianity, when applied to hell (which, it has been argued, was viewed through a lens of geographical neutrality) the comparison in fact buttressed the Jewish sense of uniqueness and legitimacy. Just as Judah Moscato could justify his use of non-Jewish sources (specifically, the rhetorical works of Agricola and Cicero) by arguing that “for to me, these foreign streams flow from our Jewish wells,” so too Ravenna, Fano, and Yagel could easily have argued that the layout and structure of hell had already been presented in ancient rabbinic texts long before Catholicism, Dante, or the works of Christian cosmographers.Footnote 82 From their perspective, it was the Christians borrowing from Jewish texts, and not the reverse.

Finally, the issue of medium ought to be addressed. The handwritten annotations of Fano and Ravenna, which are terse, informal, unorganized, and haphazard, were likely not written with an audience in mind. These were almost certainly private notes written during reading as a form of physical engagement with the text—that is, a form of “book use.”Footnote 83 In Yagel's case, though he did share his book with others, he did not, it seems, have any intention of publishing his work, in print or manuscript. It is not impossible that the less public nature of these written endeavors afforded writers a more open approach to Christian sources, allowing them to engage more explicitly with potentially theologically charged issues such as hell.Footnote 84 Perhaps it is no coincidence that I have yet to find a printed Jewish source in Hebrew from the period, written for a large audience of Jews and potentially Christians, that makes similar comparisons. If this is the case, marginalia or private manuscripts may afford a glimpse into marginalized modes of thought harbored by Italian Jews but often omitted from their public works in order to avoid censure from their correligionists. It is not unreasonable to assume that Jews were aware of the parallels between Christian and Jewish notions of hell. Many of them may have identified the two discourses as two perspectives on the same place. The explicit evidence attesting to this comparison may, however, surface only in the more informal mediums that have been discussed in this article.

***

Avi Kallenbach is a PhD candidate at Bar-Ilan University. His research explores the Jewish study of kabbalah in early modern Italy through the lens of annotations inscribed in the margins of manuscripts and printed books.