INTRODUCTION

In 1581, three French pirate ships entered Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro at the worst possible time for the Portuguese.Footnote 1 The governor, Salvador Correia de Sá (ca. 1540/41–1631), had taken all his men and traveled to the sertão, the hinterland, to ambush the Tupinambá people.Footnote 2 He left behind only his wife, Inês de Sousa (ca. 1550–1602), and an administrator, Bartolomeu Simões Pereira (d. 1598), the first prelate of Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 3 As the ships came closer and closer, panic started to break out among the women, children, and priests who remained in the city.Footnote 4 There was no one to defend them, and defeat was almost certain.Footnote 5 However, Inês de Sousa had an idea. She rallied the women, placed helmets on their heads, and handed them bows and arrows ready to take aim at the ships.

According to José de Anchieta (1534–97), a Spanish Jesuit, this was a clever ruse to fool the corsairs: “There were not enough men to either attack or stand guard, [but] the Governor's wife herself, leader of the women, staged along the [city's] walls an apparent battalion of armored soldiers.”Footnote 6 The disguised soldiers lined the city's two fortresses (fig. 1), sounded the drums of war, and lit fires on the beach in the evening to give the impression of a standing army waiting to attack.Footnote 7 Meanwhile, the administrator and the elderly fathers of the Society of Jesus prayed enthusiastically for the departure of the French.Footnote 8 Although the pirates attempted to contact Bartolomeu Simões, there was to be no negotiation.Footnote 9 The cadence of the military snare doubled, and the women sentries remained in military formation. Cowed, the French weighed anchor and left Guanabara Bay, according to the report that circulated in Annual Letters of the Society of Jesus.Footnote 10

Figure 1. French map of Rio de Janeiro when it was settled by Huguenots in the 1550s. The Portuguese took the colony in the 1560s. The forts were on either side of the bay. The map is titled La France antarctique autrement le Rio Ianeiro and was adapted ca. 1800 from the 1557–78 voyages of Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon and Jean de Leri. 16.5 x 23.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE DD-2987 (9481).

José de Anchieta made clear that Inês de Sousa was “leader of the women”—an allusion to Dido, the legendary Queen of Carthage. In the Aeneid, Dido runs away from her brother, Pygmalion of Tyre, and takes his army, gold, and ships, leading Virgil to declare “the riches that the greedy man had craved voyaged the sea, and a woman led the act!”Footnote 11 In sixteenth-century Rio de Janeiro, the situation was partially reversed. Inês de Sousa led an army of women who stopped a fleet of pirates from robbing the city of its gold and caravels. Women like her hover at the edges of documents, and, as Amélia Polónia and Rosa Capelão attest, “from time to time, they became visible.”Footnote 12 Indeed, after 1581, Inês disappears from the record, at least until an English cabin boy met her ten years later, during a skirmish with Dutch pirates.Footnote 13 Her husband was once again absent, and it fell to Inês to arm her English servant to protect Rio de Janeiro from a sack. The last mention of Inês de Sousa occurs in 1599, during an ill-fated return to Portugal.Footnote 14 Beyond that, it seems that she died sometime before 1602, because her husband remarried that same year.Footnote 15

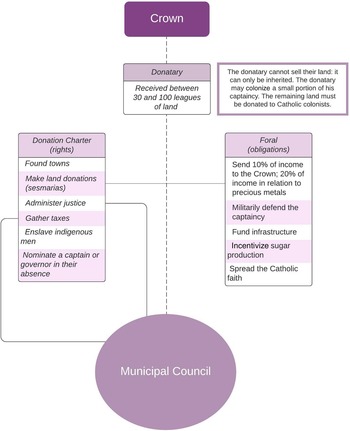

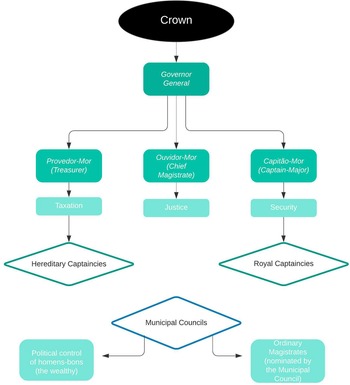

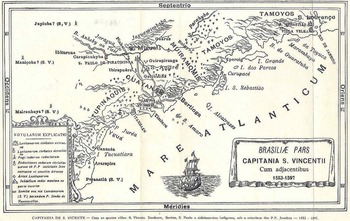

The tale of Inês de Sousa's ingenuity and resilience is one of many episodes of female governance in sixteenth-century Brazil. Inês and several other European women, the wives and widows of the first Portuguese settlers, temporarily governed hereditary and royal captaincies in the absence of their husbands. Between 1534 and 1536, the Portuguese king, João III (r. 1521–57), began distributing land to fidalgos (minor nobles) who were instructed to colonize the “lands of Brazil.”Footnote 16 Through the captaincy system, João III issued royal grants to twelve donatários (donataries) (see fig. 4).Footnote 17 In exchange for bearing the cost of settling and protecting the newly established colonies, the royal grant endowed each donatário with expansive judicial, pecuniary, and administrative powers (see fig. 2).Footnote 18 However, seven of the hereditary captaincies failed, and two more were sold by heirs to the Crown.Footnote 19 In response, João III established the Governorate General of Brazil in 1548, and the first governor general, Tomé de Sousa (1503–79), arrived the following year.Footnote 20 Although Tomé de Sousa was officially the highest power in Brazil, the successful hereditary captaincies continued to operate with nominal supervision, or none at all in the case of Pernambuco (see fig. 3).Footnote 21 During the Philippine Dynasty (1580–1640), the unification of Portugal and Spain under three Habsburg kings named Philip, further administrative units were created, and Portuguese America was a mixture of hereditary captaincies, royal captaincies, and states.Footnote 22

Figure 2. The hereditary captaincy system. Produced by the author.

Figure 3. The governorate general system. Produced by the author.

Historians have suggested that the fractured and inconsistent nature of Portuguese colonial administration in America allowed for flexible, decentralized, and plural models of governance that reflected local exigencies.Footnote 23 In the captaincies, this occasionally resulted in women collaborating with administrators, city councils, or religious leaders to defend the interests of their husbands and children. Ana Pimentel (fl. 1522–ca. 1570), Beatriz (Brites) de Albuquerque (1517–84), and Luisa Grimaldi (1551–1636) temporarily governed the hereditary captaincies of São Vicente, Pernambuco, and Espírito Santo, respectively.Footnote 24 These women managed their husbands’ territories, and evidence of their provisional governance indirectly survives in the work of missionaries and later chroniclers. Although scholars have mentioned these women in early histories of colonial Brazil, there has been little interrogation of the legal and social norms that enabled Ana, Luisa, and Brites to step into gubernatorial roles. Yet, understanding the circumstances that led European women to take an active role in the colonization of the Americas will not only lead to a more nuanced understanding of Portuguese colonial administration, but it will also illuminate the ways in which governadoras exercised cultural and legal power over colonial subjects.

Figure 4. Map of Brazil in 1534. The parallel lines demarcate the hereditary captaincies. The colored portions demarcate the traditional lands of different Indigenous peoples ca. 1500. The map of the captaincies is based on the work of Jorge Pimentel Cintra, “Reconstruindo o mapa das capitanias hereditárias,” Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material 21 (2013): 11–45. The distribution of Indigenous peoples is based on Atlas histórico escolar, 8th ed. (Rio de Janeiro: FAE, 1991), 12. Produced by the author.

In Europe, historians have broadly shown that elite Iberian women, especially widows, entered political, commercial, and juridical spaces to oversee their families' proprietary interests.Footnote 25 At times, this extended to regencies of counties, duchies, and even kingdoms, before their sons came of age.Footnote 26 In Portugal, partible inheritance laws, which permitted the division of inheritance among male and female heirs, gave women greater testamentary rights than other European jurisdictions.Footnote 27 As Darlene Abreu-Ferreira has shown, this meant that Portuguese women could, in theory, manage entailed property, inherit public offices, and challenge financial misconduct.Footnote 28 Nevertheless, early modern Portuguese law and practice were not, prima facie, egalitarian.Footnote 29 Women were, in many ways, constrained by the main sixteenth-century compilation of Portuguese norms, the 1512 Ordenações Manuelinas (Manueline ordinances). The Ordenações were based on principles of natural law, canon law, and traditional customs that, in sixteenth-century Portugal, maintained women's inherent mental and physical inferiority to men.Footnote 30 For example, the Ordenações excluded women from the line of succession, the judiciary, and public office.Footnote 31

Even so, the Ordenações were not a legal code—that is, a systematic, coherent, and exhaustive collection of laws—but, rather, a compilation of juridical precepts.Footnote 32 As António Manuel Hespanha has shown, early modern Portuguese law was characterized by a plurality of sources that included not only the Ordenações but also doctrinal debates, European common law, Roman law, canon law, customs, and royal interventions.Footnote 33 Indeed, many Manueline precepts explicitly stated that subjects could petition the king for a graça (grace) or mercê (mercy).Footnote 34 For example, one of the couples examined in this essay, Ana Pimentel and Martim Afonso de Sousa, received special dispensation from João III, “because it is [a] just cause” to ensure that their property was inherited by, in the first instance, Pimentel's sister, and, later, a niece, Mariana da Guerra.Footnote 35 Such a dispensation was necessary because the Ordenações Manuelinas prohibited women inheriting lands donated by the Crown, “except by special donation or mercê.”Footnote 36 Likewise, any income inherited as a result of holding those lands could not be inherited by women, “except by our special graça.”Footnote 37

The flexibility of the Ordenações Manuelinas and the plurality of justice in early modern Portugal and its colonial possessions made it possible for women to inherit or manage lands where permission to do so was appropriately granted and recorded by the Crown or its representative. It is a result of these legal mechanisms that the activities of the women examined in this essay survive with such vigor: the question of whether or not each woman had the power to make decisions was of critical importance to colonists who received sesmarias (land grants) during their periods of governance. Sesmarias originated in a fourteenth-century agricultural law and were utilized in the colonies to encourage production.Footnote 38 However, obtaining a land grant was not a simple process: it required both the captain and the governor of the captaincy to review the request, followed by a review by the ouvidor (Crown judge), as well as occasional supplementary documentation from witnesses.Footnote 39 If the grant were successful, it would be registered by the local government and the beneficiary had to request Crown approval through the Conselho Ultramarino (Lisbon overseas council) within a year.Footnote 40 If Ana, Luisa, or Brites were not entitled to donate Crown land to colonists, then the livelihoods of many individuals who had invested significantly in the hectares of land claimed in each captaincy would be jeopardized.

Sesmarias are demonstrative of how the legal and social norms of Portugal were transported to their colonial possessions, where they interacted with and were adapted by colonial and frontier agents.Footnote 41 Ana, Luisa, and Brites negotiated these norms in the colonial space and their actions have been captured in a variety of contemporary sources. Despite such documentary evidence, however, there has been little written about how European women protected their patrimony in the first century of colonization in Portuguese America.Footnote 42 This is perhaps due to the fractured nature of the sources, which has somewhat constrained the study of women and gender in sixteenth-century Brazil, with notable exceptions in the fields of cultural history and the history of sexuality.Footnote 43 That being said, historians have extensively examined women's inheritance in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the 1980s and 1990s, anglophone scholars studied dowries, familial relationships, and inheritance to investigate how shifting laws and customs affected colonial women.Footnote 44 More recent lusophone scholarship rooted in feminist jurisprudence has further expanded our understanding of women's legal status and limitations in the colonies, with a particular emphasis on female agency. Luisa Stella Coutinho and Vanessa Massuchetto, in particular, have used legal documents to shed light on the experience of being a woman in the colonies, drawing out women's voices in polyphonic juridical narratives, and revealing the canny manipulation of social norms by women to achieve their desired legal outcomes, including land ownership.Footnote 45

While no personal writings survive for the four women under analysis, there are many sources that shed light on their lives. There is, for example, the final will and testament of Ana Pimentel and her husband, as well as a seventeenth-century deposition given by Luisa Grimaldi to interrogators in favor of the beatification of the aforementioned José de Anchieta.Footnote 46 There are also Portuguese and Jesuit archival sources that reference actions taken by some of these women—for example, the donation of land and the disbursement of funds.Footnote 47 Finally, in terms of published sources, there are chancery documents and travel narratives, including the diaries of the Portuguese fidalgo Pero Lopes de Sousa (d. 1594), the English privateer Thomas Cavendish (1560–92), and one of his cabin boys, Anthony Knivet (fl. 1591–1649), who made an ill-fated attempt to sack Espírito Santo.Footnote 48 Similarly, early chronicles, like the Tratados da terra e gente do Brasil (ca. 1583–1601), by the Jesuit Fernão Cardim, and Tratado da Terra do Brasil (1576), by the historian and statesman Pêro de Magalhães Gândavo (1540–80), can be used to contextualize each woman's role in the growth and expansion of the Portuguese colonies.Footnote 49

In the eighteenth century, a handful of Portuguese historians also transcribed archival sources that have now been lost due to fire and flood. The books of sesmarias issued in São Vicente were destroyed by high water of the Tietê River in the early twentieth century, but Gaspar Teixeira de Azevedo, better known as Frei Gaspar da Madre de Deus (1715–1800), transcribed many of these and other administrative minutiae in his Memórias para a história da Capitania de São Vicente (1797), as did his contemporary Marcelino Pereira Cleto (1745–94), a magistrate whose personal writings on the history of São Paulo are held in Portugal.Footnote 50 In Pernambuco, there are slivers of correspondence, but much of the first three decades of Pernambuco's history was transmitted orally to men like Frei Vicente do Salvador (1564–ca. 1635), who wrote a history of Brazil in the early seventeenth century.Footnote 51 In Espírito Santo, the books of the municipal government were taken to Rio de Janeiro at some point in the nineteenth century, and subsequently disappeared, but a transcription of one of the most important land grants issued by Luisa Grimaldi survives at the National Library of Brazil.Footnote 52 While these compilations are selective based on each writer's religious and political affiliations, they do offer a tantalizing glimpse of the extent of each woman's colonial influence.Footnote 53 Drawing upon these varied letters, administrative documents, and chronicles, this essay argues that governadoras played a significant but understudied role in the Portuguese conquest and colonization of Brazil. Examining the extent and breadth of their responsibilities, and the legal and social triggers that activated or deactivated their authority, will lead to deeper understandings of women as imperial agents who wielded power against colonial subjects in select circumstances.

ANA PIMENTEL AND THE INITIAL COLONIZATION OF SÃO VICENTE (1534–46)

Ana Pimentel was the wife of Martim Afonso de Sousa (1500–64), the first donatary of the captaincy of São Vicente. Although the Portuguese first arrived in 1500, there was no attempt to settle the roughly 5,000 kilometers of Atlantic coastline they had claimed under the Treaty of Tordesillas beyond a few fortified trading posts (feitorias) occupied by a resident factor and merchants contracted by the king.Footnote 54 However, the steady increase of French trade with the Tupinambá threatened the Portuguese monopoly on brazilwood.Footnote 55 The increased competition from the French, in addition to declining profits in India, convinced João III to send five vessels loaded with four hundred colonists and crew to combat the French, search for gold, and establish the first settlements on the coast.Footnote 56

Martim Afonso de Sousa, captain-major of the mission, and his brother, Pero Lopes de Sousa, led the colonists southward down the Prata River and eventually founded the city of São Vicente (fig. 5) in January 1532.Footnote 57 Upon his return to Portugal, João III rewarded Martim Afonso for the three years spent experiencing “many hardships, much hunger, and many torments” with one hundred leagues of coastline and the captaincy of São Vicente.Footnote 58 Yet Martim Afonso never returned to Brazil.Footnote 59 Shortly after docking in Lisbon, he was promoted to Captain-Major of the Sea and sent to serve in India.Footnote 60 Therefore, like many other men in the king's service, he left the management of his business affairs to his wife, Ana Pimentel.Footnote 61

Figure 5. The captaincy of São Vicente. The map appeared in Benedicto de Jesús Calixto, Capitanias paulistas, 2nd ed. (São Paulo: Duprat e Mayenca, 1927), xvi.

Between 1534 and 1549, Ana managed her husband's Brazilian and Portuguese interests while he served in India.Footnote 62 São Vicente flourished under her oversight due to several key decisions she made that affected the pace and success of colonization at a time when most Portuguese attempts failed. Although very few European women played a role in the early colonization of Brazil, select women like Ana Pimentel exercised a degree of agency in colonial affairs—as long as it directly assisted their menfolk. This agency has largely been erased in contemporary and later historical narratives, which gloss over the substance and significance of their contributions. However, reading these records confirms that colonists in São Vicente recognized Ana Pimentel's authority and the privileges she could grant because her name and mandates were used to justify the land they received, and the slave raids they initiated. Although she was a woman, she possessed temporary power over colonists, and contributed to the invasion and exploitation of the one hundred leagues of coastline her husband received.

Ana Pimentel was a Castilian noblewoman from the town of Salamanca in western Spain.Footnote 63 She met Martim Afonso when he accompanied Manuel I's widow, Eleanor of Portugal (1498–1558), to Castile in 1522, and they married the following year.Footnote 64 Diogo de Couto (1542–1612), a Portuguese chronicler, and Gil Vicente (ca. 1465–ca. 1536), a troubadour, both wrote that the pairing was a love match.Footnote 65 In 1525, the couple returned to Portugal with Catherine of Austria (1507–78), who had married the Portuguese king by proxy.Footnote 66 Although they belonged to the nobility, the couple was not yet independently wealthy and even had to sell one of Martim Afonso's hereditary titles to the Crown in order to repay a loan.Footnote 67 It was therefore vital during his long absences that the remainder of their patrimony was kept intact.

Ana Pimentel was legally empowered to manage her husband's affairs due to “a public instrument of a procuration” executed at the residence of Jaime I, Duke of Bragança (1478–1532), Martim Afonso's former lord.Footnote 68 The document vested Ana with all the rights and powers of her husband and gave her the ability to make decisions in his name.Footnote 69 These decisions mostly turned on the issue of money. When Martim Afonso first arrived in India in 1534, he wrote to his cousin, António de Ataíde, Count of Castanheira, and instructed him twice to make payments to his wife.Footnote 70 In turn, Ana Pimentel received and disbursed funds: she authorized payments to her husband's creditors in 1542 and accumulated other assets using their joint income.Footnote 71 It is possible that she also facilitated payments to the Society of Jesus, because Francis Xavier (1506–52), writing in Goa, asked Ignatius Loyola (1491–1556) to send a pair of rosaries to the governor, Martim Afonso de Sousa, and his wife, Ana Pimentel.Footnote 72

Ana Pimentel's reputation for meticulous financial management succeeded her. Prior to her husband's return from India, she had managed to amplify their collective wealth by purchasing hereditary titles and lands with generous pensions.Footnote 73 In the eighteenth century, the Portuguese chronicler Francisco de Santa Maria (1653–1713) wrote a fictitious dialogue to dramatize the relationship between Catherine of Austria and Ana Pimentel in one of his yearbooks.Footnote 74 The queen asked Ana, “Why are you creating such beautiful houses for when Martim Afonso comes [home]?” Ana replied that she wanted to be prepared should Martim Afonso “return [from India] poor.”Footnote 75

Ana Pimentel's supervision, however, extended into the Atlantic. As procuradora, she had also been vested with the responsibilities of the captain of São Vicente. The donataries had to pay for the costs associated with the justice system, defense, and administration, in addition to colonizing the land. Although the Crown had given the land to Martim Afonso, he could not sell it, and he and other donatários were charged with rendering it productive for the Crown—that is, they had to generate imposts for the Crown, otherwise they would lose the right of possession.Footnote 76 Each donatário could claim one-fifth of the donated land, the remainder of which had to be given to suitable colonists.Footnote 77 As a result, many of the captaincies failed.Footnote 78 The inability to sell the land meant that the only way to prevent substantial losses was to build commercial infrastructure, principally sugar mills, which required enslaved Indigenous labor.Footnote 79 Many settlements failed due to Indigenous raids and a lack of interest from either the donatary or prospective colonists.

Ana Pimentel made several key decisions that ensured that São Vicente became one of the few Brazilian captaincies that thrived.Footnote 80 Although none of her personal writings survive, the procuration is repeatedly referred to by early settlers and missionaries to justify their land claims.Footnote 81 In the eighteenth century, Frei Gaspar da Madre de Deus (1715–1800) found a manuscript, now lost, at the archives of the Convento de Carmo de Santos.Footnote 82 He noted that it was based on a copy that had been reproduced five times by four different notaries—thrice for the municipal council of São Vicente and twice for the governate-general.Footnote 83 It contained a number of transcribed documents, including a copy of the procuration signed by Martim Afonso de Sousa on 3 March 1534 in Lisbon.Footnote 84

It is significant that the municipal council of São Vicente first copied the procuration. The municipal council worked closely with the donatary or his representative governor, who, in the case of São Vicente, was appointed by Ana Pimentel until the mid-1540s.Footnote 85 The first four governors of São Vicente—Gonçalo Monteiro in 1536, António de Oliveiro in 1538, Christovaõ de Aguiar de Altero in 1542, and Brás Cubas in 1544—were appointed by the procuradora in documents registered in Lisbon and in copies subsequently taken to Brazil.Footnote 86 The procuration made it clear that Ana Pimentel had the authority to appoint governors in her husband's absence. The governor then had the power to issue land grants and to appoint notaries, magistrates, and factors, as well as members of the municipal government, in the name of the donatary or his procurator.Footnote 87

Although there is limited direct evidence of Ana Pimentel's collaboration with each governor, there are some clues. In the eighteenth century, Marcelino Pereira Cleto found evidence that the township did not have a prison until 1544.Footnote 88 That year, the city councillors expressed their frustration to the governor because the justice system was one of the responsibilities of the donatary.Footnote 89 The governor claimed that construction was underway, that Ana Pimentel had already paid for the iron to build the prison, and that the stone needed would be taken from the township's production.Footnote 90 The anecdote suggests that she took her responsibilities as donatary seriously and disbursed funds to assist with the construction and defense of the colony.

Ana Pimentel's name was also invoked in the correspondence of the Society of Jesus to substantiate their claims to land where they had constructed a college. In 1553, Benedito Calixto penned a memorandum that outlined the legal rationale behind the donation of land from Pero Correia to expand the Jesuit College.Footnote 91 The land was originally given to Correia by the second governor, António de Oliveira. Calixto explained that António Oliveira arrived in São Vicente and presented the municipal government and “people of this town a public instrument of power and procuration that seems to have been issued in Lisbon on 16 October 1538.”Footnote 92 Oliveira was empowered by “D. Ana Pimentel, wife of the said Governor, her procuration being enough for [Oliveira] to do what he thought best for the administration of the lands . . . in the name of both [Martim Afonso and Ana Pimentel].”Footnote 93 The Jesuits had only arrived in 1549, and the captaincy system had only been used previously in the uninhabited Atlantic islands off the coast of West Africa. Therefore, Calixto had to carefully explain that Ana Pimentel and her appointed governor had the power to grant land, as well as take it away if it were misused or abandoned. Calixto himself inspected the book of sesmarias, now lost, in which he found a record of the lands granted to Pero Correia, who then donated them to the Society of Jesus.Footnote 94 Therefore, their plans to expand the Jesuit College could continue lawfully.

Even one hundred years after Ana Pimentel's tenure, colonists still invoked her name to justify possession of the land. In a 1664 document held at the Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo, a settler set forth the colonial history of a tract of land that was first given to a settler named Rui Pinto, who had died.Footnote 95 According to the document, Pinto was given the land by Gonçalo Monteiro, who was empowered by “donna Anna Pimentel” to issue land grants on behalf of her husband. Interestingly, the document refers to the “lands of Senhora Dona Anna Pimentel” first, and then to “the aforementioned Senhor, her husband who gave her [these lands] to give to whomever she wanted in the name of both of them.”Footnote 96 The settler then lists the governors empowered by Ana Pimentel to justify the initial land grant, and the subsequent ownership, held by different individuals, following the death of Pinto until the year 1664.

During Ana Pimentel's tenure, there were two decisions that significantly altered the trajectory of her husband's colony. The first is in relation to the prominent colonist Brás Cubas (1507–92), who took possession of an area that bordered Enguaçu, occupied by the Tupiniquim, along the River Jurubatuba (fig. 5).Footnote 97 The several leagues of land were previously occupied by Henrique Montês, who had died in 1534.Footnote 98 Cubas, a former criado (servant) of Martim Afonso, petitioned Ana Pimentel for the right to possession of Jurubatuba.Footnote 99 According to the Ordenações, an individual who had been granted a sesmaria was required to cultivate it immediately. If the land were abandoned, then the person in possession of the land could lose the land grant.Footnote 100 Cubas was also a crew member of Martim Afonso's original 1530 expedition and had returned to Portugal to make the request personally at Ana Pimentel's residence in Lisbon.Footnote 101

On 25 September 1536, Ana Pimentel extinguished the rights of Henrique Montês's heirs, and granted Brás Cubas the right to possession of two to three leagues of land in Jurubatuba.Footnote 102 She claimed that Montês did not have a written grant from Martim Afonso, and without written evidence his heirs could not inherit the land.Footnote 103 Instead, she granted Cubas the right to possession, “without the permission to sell or even donate or exchange or subdivide” a plantation called Enguaçu.Footnote 104 The document was witnessed by her son's tutor António de Freitas, António Delgado, and the notary António Luis, who executed the document in Lisbon.Footnote 105 Cubas first sent his father, João Pires, to Brazil in 1537 to take possession, but the Tupiniquim impeded him.Footnote 106 Cubas obtained another grant from Ana Pimentel in 1540, which instructed the governor, Antonio de Oliveira, to demarcate the lands belonging to Cubas and to assist him with possession.Footnote 107 When Luís de Góis challenged Cubas's right to the land in the 1550s, Martim Afonso, who had returned to Lisbon, affirmed the latter's land rights and stated that his wife's original donation was “as valid as if it were written by me.”Footnote 108

Ana Pimentel's second major decision was even more controversial. Since returning to Brazil in 1540, Cubas had quickly taken advantage of the favorable climate of Jerutuaba. He had obtained permission to build a sugar mill that benefited from the nearby lagoon.Footnote 109 Cubas used the profits to transform Enguaçu into an attractive settlement: he funded and built a port, a chapel, and a hospital, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Todos os Santos, in 1543. By contrast, the founding township of São Vicente had suffered damage from a strong undertow off the coast. Although a new settlement was built inland, many colonists chose to move to Enguaçu, which had been renamed Santos after the hospital.Footnote 110 But they were still not satisfied. They wanted to move inland to the verdant plateau, where conditions were more favorable for agriculture. There was, however, a prohibition in place. The Tupiniquim patrolled the hinterland, called the Piratininga, and Martim Afonso feared that any attempts at settlement would provoke war.Footnote 111 Possibly at the behest of Brás Cubas, Ana Pimentel repealed her husband's prohibition in 1544.Footnote 112

On 11 February 1544, Ana Pimentel issued an alvará (permit or charter) that allowed “residents of the captaincy of São Vicente to go and resgatar (purge) the plateau.”Footnote 113 Resgatar ordinarily referred to the abduction and enslavement of Indigenous peoples.Footnote 114 To this, Ana Pimentel added:

I declare, that in the periods in which the Indians of the said plateau attend to their spiritual activities, no one of any description may go to the said plateau, having been informed that there is great danger in going to that land during that time.Footnote 115

She reiterated that no one, not even the captain or the ombudsman, could make any exceptions: “In this way, I order all magistrates to enforce the law because this is for the good [of all].”Footnote 116 Thus, the alvará legally empowered colonists to go to the plateau, enslave Indigenous men and women, and form new settlements. Previously, only the Portuguese degredado (exiled convict) João Ramalho (1493–1580), son-in-law of the Tupiniquim chief Tibiriçá, was permitted to act as a go-between in the transaction of enslaved Tupiniquim.Footnote 117 News of the alvará reached São Vicente a few months later through Antônio Teixeira, who brought the alvará of the donatária (woman donatary), where city councilors recorded it on 1 May 1544.Footnote 118 A woman had, effectively, given the order to enslave further Indigenous men and women and invade their lands.

The repeal of the prohibition on movement between the coast and the plains of Piratininga had wide-ranging effects. Frei Gaspar da Madre de Deus reported that many colonists abandoned the original settlements in favor of the plateau, which was better suited to agriculture.Footnote 119 By the 1550s, the governor had moved to the village established by João Ramalho, which became a township, Santo André, in 1553.Footnote 120 They even moved the pelourinho, the stone column placed in the town square to publicly punish criminals.Footnote 121 In 1554, José de Anchieta and Manuel de Nóbrega founded the Jesuit college São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga, predecessor of the metropolis of São Paulo.Footnote 122 The mission sat between the Tamanduateí and the Anhangabaú rivers and benefited from an alliance with the converted Tibiriçá, whose men assisted the Jesuits with matters of defense.Footnote 123 Ana Pimentel's decision was praised indirectly by Anchieta, who remarked upon the splendid climate and growing conditions of the Piratininga.Footnote 124 These conditions may have been due to Indigenous burning practices that enabled agricultural production of tubers and grains.Footnote 125

Ana Pimentel's tenure ended in the 1540s when Martim Afonso de Sousa returned from India.Footnote 126 However, her governance stimulated significant growth on behalf of her husband: by 1548, there were more than six hundred colonists and over three thousand enslaved Indigenous men and women.Footnote 127 Although she was not actively involved in the daily elements of colonial life, she appointed the governors of São Vicente and made astute decisions concerning land grants and further colonization. The evidence that survives makes it plain that contemporaries invoked her name to validate their land claims and protect their interests. While this evidence is mostly deployed in narratives that articulate the success of early Portuguese men, it is possible to retrieve, in part, the rationale behind Ana Pimentel's decisions by placing them in their historical context. She managed her husband's assets and likely had access to the royal court. She understood the importance of ensuring that São Vicente was governed in a way that reflected the king's mandate, so that her family would receive greater favor. Equally, Ana Pimentel pursued financially lucrative decisions, like the move to the plateau, to support the growth of the family's patrimony: more sugar mills and plantations represented increased taxable production. Her husband's later actions in support of further women governors, such as Mariana da Guerra, suggests that the importance of preserving patrimony trumped strict adherence to patriarchal models. It was in these situations that women played more active roles in the imperial project.

BRITES DE ALBUQUERQUE AND PERNAMBUCO (1540–41, 1554–60, 1570/72–82)

In March 1535, Brites de Albuquerque and her husband, Duarte Coelho (ca. 1485–1554), the first donatary of the captaincy of Pernambuco, arrived in northeastern Brazil.Footnote 128 Theirs was not a peaceful arrival. The Portuguese settlers almost immediately entered into conflict with the Caeté people of the Tupi nation, who lived between the Opara (São Francisco River) and the island of Itamaracá (fig. 6).Footnote 129 Coelho's armada had arrived at the port of Marcos, near Itamaracá, which, fortunately for him, had a royal factory. The Portuguese traders assisted Coelho as he drove the Caeté away from the shores of the mainland, where Coelho funded the settlements of Iguarassu and Santa Cruz. Within a couple of years, the donatary had moved farther south and established the towns of Olinda and Recife in 1537, the latter of which became the first slave port in the Americas.Footnote 130

Figure 6. The captaincy of Pernambuco (where Duarte Coelho landed). The island of Itamaracá is in the middle where a feitoria (trading post) once was. This engraving by Theodore de Bry first appeared in Americae tertia pars: Memorabile provinciae historiam continue (Frankfurt am Main, 1592).

Within twenty years, Pernambuco had become the wealthiest captaincy in colonial Brazil.Footnote 131 The source of Pernambuco's vast fortune was the export of sugar cane derived from slave labor.Footnote 132 In search of financial backers for further sugar mills, in 1540 Coelho left Pernambuco in his wife's hands for the first time and traveled to Portugal.Footnote 133 Few records survive from this period, but signs point to Brites as a capable administrator who, as the daughter of a Portuguese nobleman, had some exposure to household management during her childhood and adolescence.Footnote 134 Although she was distantly related to the royal line, her family had lost its fortune over the centuries, and her union with a wealthy soldier of fortune was typical of the period, one that ennobled not only her husband but also his sons.Footnote 135 As one seventeenth-century commenter labeled it, Brites's father's “fortune was his noble linage and nothing more, and this he gave as her dowry.”Footnote 136 Together, they invested a significant amount of the riches Coelho had amassed in southeast Asia between 1511 and 1530 into the colonization of Pernambuco and the export of sugar cane.Footnote 137

Following the death of her husband in Portugal in 1554, Brites de Albuquerque assumed control of the captaincy.Footnote 138 Over the next thirty years, Brites consolidated her husband's initial colonization of the sixty leagues of land he had received along the northeastern coastline of Brazil. She accomplished this through the patronage of the various missionary groups that began arriving throughout the sixteenth century—especially the Jesuits, who created aldeias (Indigenous villages administered by the Society of Jesus) for converted Indigenous women and men—and, presumably, through the continued support of the sugar cane industry, particularly through the import of enslaved Africans from Guinea.Footnote 139 Her involvement as an imperial agent is elided in the sources that remain from this period, which instead praise her maternal qualities. A close reading of the anecdotes and land grants that mention her by name, however, suggests that she was a canny and experienced administrator, who, empowered by her late husband's mandate, consolidated his authority and that of the Portuguese Crown through colonial exploitation that significantly enriched her family.

Brites was assisted by her brother, Jerônimo de Albuquerque (ca. 1510–84), who had formed an alliance with the Tindara, a Tabajara people.Footnote 140 He had married Muira Ubi, daughter of the morubixaba (chief), Uirá Ubi, who supported the Portuguese on many occasions against the continued raids by the displaced Caeté people. Although Brites had sons, Duarte Coelho de Albuquerque (b. 1537) and Jorge Coelho de Albuquerque (b. 1539), both born in Olinda, they were studying in Portugal and did not immediately take control of the captaincy.Footnote 141 In the interim, their mother remained “governadora and administradora of her son, Duarte Coelho de Albuquerque, heir and successor to this captaincy,” as confirmed by a land grant issued by her to Duarte Lopes on 20 May 1556.Footnote 142

The major challenge faced by Brites during her second administration was the Caeté uprising. In 1555, Jerônimo de Albuquerque sent a letter to the king requesting assistance from the metropole. However, Olinda was under attack and would fall without reinforcements.Footnote 143 Sugar mills and stations had been destroyed, and the Caeté had surrounded Olinda, preventing the colonists from moving more than two leagues in any direction from the capital.Footnote 144 The war continued for several years until the death of João III in 1557. The king's widow, Catherine of Austria, ordered Duarte Coelho de Albuquerque and his brother to return to the colony and push back the Caeté. Their return was followed by several successful assaults on the tribe, pushing Indigenous families back to the hinterland.Footnote 145

Although the brothers remained in the captaincy during the 1560s, Duarte Coelho de Albuquerque decided to return to Portugal in 1572. Brites de Albuquerque once again assumed control of the captaincy based on an instrument registered in the record books of the monastery of São Bento of Olinda.Footnote 146 However, between 1573 and 1576, she nominated her second-born son, Jorge Coelho de Albuquerque, to administer the captaincy, perhaps as a training exercise. However, Jorge also left and nominated his uncle, Jerônimo de Albuquerque, to act as captain-major between 1576 and 1580, alternating with Cristóvão Soares de Melo, Jorge's father-in-law.Footnote 147 Brites continued to govern alongside these men, as the captain-major position largely related to the defense of the colony.Footnote 148 Unfortunately, her sons died at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578, and documents after this date promoted her to capitoa (woman captain). Footnote 149

In 1579, Brites confirmed a land grant in Camaragibe to the Society of Jesus. She also confirmed a land grant in favor of the Church of Nossa Senhora do Monte in 1582.Footnote 150 In both of these documents, she declared herself as, or the scribe declared her to be, “Capitoa [woman captain] and governadora [woman governor] of this captaincy of Pernambuco, the town of Olinda of Nova Lusitania, territories of Brazil in the name of El-Rei, Our Lord.”Footnote 151 Previous land grants had referred to her as governadora or as her husband's widow, but, almost thirty years after her husband's death, she was recorded as the captain of Pernambuco in the absence of any kinsmen who otherwise had a viable claim.

Capitoa was perhaps used to draw attention to the authority she now possessed by virtue of her late husband's carta de doação (donation charter that established possession of the land) and foral (a juridical document issued by the king that established the rights, jurisdiction, and taxation obligations of the donatary), and in the absence of her sons. A useful case study of this evolution can be found in Jesuit records. The first recorded Jesuit encounter with Brites de Albuquerque is in 1551 as the unnamed but virtuous wife of Duarte Coelho.Footnote 152 The Jesuits stayed in Pernambuco until 1554 and returned seven years later, in 1561. This time, they went immediately to Brites, now named, whom they called the “guovernadora of this captaincy.”Footnote 153 Pereira told his colleagues in Portugal:

The Lady Governadora, who is called D. Breatriz [sic] is extremely devoted to the Company. When we arrived, she was at one of her sugar mills, about a league away from the city. They say she spent that entire night being unable to sleep with excitement because she [only] learned [that we were here] later in the day, as she had been with her niece, who was quite unwell. As soon as it was morning, and without us knowing, she was already at our church. She was so thrilled to see us that there was nothing she could do except cry and speak from the heart to show how much she wanted us there. This Lady, as I said, is very devoted to the Company, and her alms will be continual as long as there are Fathers of the Company here, as there are now. Her practices are going to the church and hearing mass and giving herself to God, visiting those unwell in the town and consoling them. She enjoys speaking about God and reading spiritual books, and now that her sons are returning, she cannot hide her happiness to see them and relieve herself of governance and have more time to devote herself to God.Footnote 154

Brites did not attract nearly the same level of attention or detail as Pereira's predecessors in 1551. Instead, their attention was focused on Duarte Coelho and his decisions, which had produced “deep-rooted and old sins” in the colony.Footnote 155 However, in the following decades, Jesuit documents regularly praised the administration of the governadora. Footnote 156 It is worth noting that the language used in these sources is deeply gendered: she was called the “woman governor and mother of Pernambuco” by José de Anchieta and described as having treated the colonists like her own children by Vicente do Salvador.Footnote 157 Talking about Brites in maternal terms was perhaps a way of reconciling the vast influence a single woman exercised in the absence of men, relating her to other spiritual mothers whose guidance allowed their children to reap the rewards of her supervision.

Brites de Albuquerque, however, did not appear to be the total embodiment of feminine humility that Rui Pereira depicted in 1561. An anecdote survives recounting how Brites had an intense disagreement with one of Pernambuco's wealthiest men in 1576. A Jesuit priest mediated the conflict, persuading both individuals to kneel before the other. The priest placed a cane in the hands of each and instructed each individual to strike the other as they pleased. They refused and chose to discuss the issue again peacefully, eventually resolving the quarrel without violence.Footnote 158 It is possible that this may have been an instance of Brites de Albuquerque asserting her authority against a recalcitrant sugar mill owner who resisted her mandate, but there is no further access to the context of the disagreement, or indeed little else in her thirty years at the helm of Pernambuco.

Despite a lack of administrative records, Brites's collaboration with the Jesuits shows that she was a woman of considerable authority and means. She deputized a priest, Simão Rodrigues Cardoso, as lieutenant of Pernambuco between 1580 and 1592 and made a number of donations to the Jesuit college.Footnote 159 Just prior to her death, she offered 250 escudos to the Society of Jesus to assist with construction costs, which they exchanged for 821,250 reis, approximately 684 times the average monthly salary of a common boatman.Footnote 160 During her final days, the Visitor, Cristóvão de Gouveia, and his secretary, Fernão Cardim, arrived in Pernambuco and consoled her as she suffered through an undisclosed illness. She died in the summer of 1582, her exequies hosted by the Jesuit college and overseen by the bishop António Barreiros, who gave the eulogy.Footnote 161

During Brites de Albuquerque's tenure as governor, Pernambuco continued to expand. According to Fernão Cardim, Pernambuco had around twenty-three sugar mills in 1570; by the time of Brites’s death, it had sixty-six sugar mills that produced 200,000 arrobas (2,940 tons) of sugar per year.Footnote 162 The cities of Pernambuco had also grown, with over two thousand colonists, around two thousand enslaved Africans, and fewer Indigenous peoples.Footnote 163 While many extant sources make claims about Brites's prodigious maternal instinct, the reality of Pernambuco's expansion suggests that she continued what her husband had started: incentivization of slave labor, the construction of sugar mills, and the protection of her patrimony. Nevertheless, her governance ensured that Pernambuco grew in the absence of her husband and sons, and her collaboration with missionary orders and the municipal council makes clear that she was a trusted figure in the community. By looking at the surviving documentation as a composite whole and contextualizing broader accounts of the captaincy's growth, it becomes clear that Brites, like Ana Pimentel, was an astute financial and political operator who had a significant impact on the colonial success of Pernambuco in the latter half of the sixteenth century.

LUISA GRIMALDI AND COLONIAL NEGOTIATION IN ESPÍRITO SANTO (1587–94)

Between 1589 and 1594, Luisa Grimaldi governed the captaincy of Espírito Santo in the absence of a suitable heir. Born in Italy, she was the daughter of Pedro Álvares Corrêa and Caterina Grimaldi, an Italian noblewoman.Footnote 164 She married Vasco Fernandes Coutinho Filho (1530–1589), the illegitimate son of the first donatary, Vasco Fernandes Coutinho (1490–1561). Coutinho had been granted fifty leagues of coastline between the Itabapoana River to the south and the Mucuri River to the north (fig. 3), which he named Espírito Santo, having arrived at a small beach (fig. 7) in modern-day Vila Velha on Pentecost in 1535.Footnote 165 Coutinho and his son faced significant Indigenous resistance from the Goitacá, Aimoré, and Tupiniquim peoples, and the captaincy almost failed on several occasions.Footnote 166 During one of the absences of the first donatary, the Goitacá and the Aimoré all but destroyed Vila Velha, forcing the surviving villagers to the banks of the Cricaré River.Footnote 167 The settlers moved to the island of Guanaani (fig. 6), then under the proprietorship of Duarte Lemos, where a new town was established, optimistically named Vitória, in September 1551.Footnote 168

Figure 7. The captaincy of Espírito Santo. The island of Vitória is in the middle. The landing site of the first donatary and the town of Vila Velha are to the right. Cavendish would have entered from the far right and tried to land where the caravel (ship) is. Villagers would have seen the ships from the adjacent mountain, Morro do Moreno, approximately 184 m in height. The map, Capitania do Espírito Sancto, is held at Real Academia de la Historia—Colección: Sección de Cartografía y Artes Gráficas; Signatura: C-003-076; Signatura anterior: C-I c 76; N° de registro: 00111.

In the same year, the Goitacá, Aimoré, and the Tupiniquim allied and prepared another attack against the settlers.Footnote 169 The Portuguese were radically outnumbered, and Coutinho requested assistance from Mem de Sá (ca. 1500–72), the third governor general of Brazil. Sá sent his son, Fernão, and nephew, Balthasar, who traveled with two hundred men in six ships to the shores of Espírito Santo.Footnote 170 Fernão died of a poisoned arrow, and Balthasar responded by brutally massacring hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Indigenous people in villages near the Cricaré River, forcing the triple alliance to concede. News of the victory reached Catherine of Austria, queen-regent of Portugal, who consoled and congratulated Mem de Sá, writing that she was pleased that “these gentiles were severely punished for the death of important men. It seems that they will not be raising their heads any time soon.”Footnote 171 The Portuguese returned to their settlements but remained confined to the small stretch of coastline by the Goitacá.

Luisa and her husband arrived twenty years later, in 1573, taking over from Belchior de Azevedo, appointed interim captain-major by the fourth governor general, Luís de Brito e Almeida (fl. 1572–78).Footnote 172 Missionary and metropole records suggest that Coutinho Filho was a prudent and fair leader whose seventeen years in charge of Espírito Santo resulted in the repopulation of abandoned land and compassionate treatment toward the Indigenous population.Footnote 173 However, he and Luisa had no children, and she governed the captaincy after his death in 1589 until a legal challenge by a relation of the first donatary was accepted by Portuguese courts.

Luisa Grimaldi was the governor of Espírito Santo for roughly four years. She used her short tenure to invite more missionaries to the captaincy to assist with converting Indigenous people and to represent her in difficult negotiations with the metropole. Most sources report on Luisa's relationship with José de Anchieta, an influential Jesuit who intervened on her behalf with the seventh governor general of Brazil, Francisco de Sousa (ca. 1540–1611), to recognize her mandate in the absence of an heir. Only once a legitimate successor was recognized by a tribunal in Portugal did the governadora return to Portugal. In the interim, her negotiation with colonial authorities and influential missionaries suggests that she exercised a degree of agency in local affairs. For example, she transferred land ownership to missionaries in exchange for assistance with her political dealings and controlled the income produced by her late husband's properties. In this way, she supported the consolidation of European colonization through her continued exploitation of the land and its peoples, which improved her financial circumstances.

The second donatary's last will and testament ensured that Luisa was entitled to an annual pension of 10,000 réis, derived from the profits of the captaincy and half of his lands, “paid to her in the said captaincy or in the kingdom, wherever she prefers.”Footnote 174 The other half of his land was granted to another kinswoman, his niece Ana.Footnote 175 However, Luisa could not inherit the captaincy. Instead, his successor would be determined by the following method:

If I die without a son by Luisa, my wife, I nominate my successor of the said captaincy to be a son of Ambrósio Aguiar Coutinho, my cousin, who is not the morgado [first-born son] but the second-born, and if the second-born dies and there is no other son who is not the morgado, then the morgado may inherit the captaincy, under these specific conditions.Footnote 176

The second-born child of Ambrósio was a woman, so his first-born son, Francisco de Aguiar Coutinho, sought to enforce his rights under Coutinho Filho's conditions. The process took four years because Francisco attempted to remove Luisa Grimaldi completely from Coutinho Filho's will. Coutinho Filho was, in fact, the illegitimate son of the first donatary, and this, Francisco de Aguiar Coutinho argued, extinguished his legal right to transfer land ownership to his widow. While the legal challenge played out in Portugal, Luisa governed Espírito Santo in Brazil. She was assisted by her brother-in-law, Miguel Antonio de Azevedo, who was married to her half-sister, Luisa Côrrea, and Marcos de Azevedo, who was married to Maria de Melo Coutinho, the granddaughter of the first donatary.Footnote 177

The major test of her leadership was in 1592, when the famed English privateer Thomas Cavendish (1560–92) attempted to sack the town of Vitória. Cavendish had been knighted by Queen Elizabeth I of England for successfully circumnavigating the globe and pilfering Spanish gold.Footnote 178 However, his second voyage ended in disaster. After returning to Brazil in 1591, Cavendish and his crew sacked the city of Santos in São Vicente, where they remained for several months.Footnote 179 This was a fatal mistake. The failure to depart on time meant they became trapped in treacherous seas at the Strait of Magellan. Many crew members succumbed to famine and freezing temperatures as they attempted to maneuver their ships to warmer climes. Off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, they sought respite in Cabo Frio, where they captured a Portuguese friar whom they found hidden in a sack of flour.Footnote 180 Fearing for his life, he told Cavendish not to bother with Santos and to head north to the fertile lands of Espírito Santo.Footnote 181

On 7 February 1592, Cavendish's fleet entered the Bay of Vitória and was met with immediate misfortune orchestrated by Luisa Grimaldi and her collaborators.Footnote 182 It was low tide, and the large English ships were almost stranded in the narrow channel.Footnote 183 The crew, angry and deprived, insisted on a final sack before returning to Plymouth.Footnote 184 Against his better judgment, Cavendish sent his best sailors, Captain Morgan and Lieutenant Royden, on two small boats to shore.Footnote 185 One headed right, toward a small fort, while another headed left.Footnote 186 They had barely entered shallow waters when their vessels began to sink under a hail of arrows.Footnote 187 Eighty perished, and “of the forty that returned, there came not one without an Arrow or two in his body, and some had five or sixe.”Footnote 188 Many more were taken prisoner by the Portuguese, surrendering with their “hands on their hair.”Footnote 189 The pirates had been ambushed by the settlers and the Goitacá—allies against a common enemy.

Vitória was in a strategic position surrounded by a rocky harbor and mountainous vantage points to keep watch over its borders (fig. 6). Luisa Grimaldi and her adjunct Miguel de Azevedo had been informed of ships on the horizon by one of their watchmen and had time to prepare. Local historians claim that Azevedo negotiated with the Goitacá chief, Jupi-açu, who sent two hundred men to assist with fortifications.Footnote 190 The colonists and the Goitacá then lit fires along the hills surrounding the bay from the Morro do Moreno to the Morro de Penedo to discourage a nocturnal attack.Footnote 191 However, it is likelier that the Jesuits brokered the agreement. José de Anchieta had arrived in Espírito Santo in 1587 and had immediately formed a close bond with Luisa Grimaldi, becoming her confessor.Footnote 192 Jesuit documentation suggests that Anchieta went to the aldeias to seek the assistance of the Goitacá against the English and was successful in doing so.Footnote 193 The Portuguese record fails to highlight the importance of the Goitacá, but Cavendish and his captured cabin boy, Anthony Knivet, both describe the accuracy and range of their arrows against English muskets.

The victory over the English pirates was recorded by the Jesuits, who used it to affirm the importance of their mission.Footnote 194 An early seventeenth-century petition that collated several reports from different captaincies argued that without the involvement of the Society of Jesus in the aldeias, many captaincies would be without a standing army.Footnote 195 In 1603, Fernão Cardim, provincial superior of Brazil, asked Pero Rodrigues to write a biography of José de Anchieta in order to celebrate the priest's conversion efforts.Footnote 196 Rodrigues reported that Anchieta had rallied not only the Goitacá but also the settlers during the Cavendish invasion. Rodrigues, who based this report on an oral account of a young settler named João Godinho, tells us that “this happened when Dona Luiza Grinalda [sic] governed the captaincy.”Footnote 197 Miguel de Azevedo is not mentioned: ten years after the attack, Luisa Grimaldi's authority was still recognized and transmitted orally.

The favorable treatment of Luisa Grimaldi in missionary sources is likely due to her philanthropy, itself a gendered activity.Footnote 198 Luisa issued land grants to the Jesuits, Benedictines, and Franciscans and offered further financial incentives to help construct churches, convents, and monasteries.Footnote 199 For example, she donated a generous portion of land just outside of the town of Vila Velha so that the Benedictines could invest in agricultural production to fund their mission.Footnote 200 The Benedictines also “stayed at the home of D. Luiza Grimalda [sic], Capitoa and governadora,” while construction was underway.Footnote 201 The Franciscans similarly benefited from Luisa's direction, being granted the site of the Morro do Moreno “from the foot of the said mountain to the top,” if, as the document suggested, the Franciscans wanted to collect stone from their new quarry to finish expanding the existing hermitage at the peak.Footnote 202 Although the original document is lost, a copy survives at the National Library in Rio de Janeiro. The copy reveals that the donation was made by Luisa Grimaldi, “governadora,” and her adjunct, Miguel de Azevedo, and recorded by members of the municipal council.Footnote 203

However, Luisa also negotiated with religious leaders to seek out their assistance in political matters. In a solitary surviving letter from José Anchieta to Miguel de Azevedo, the Jesuit revealed that he had been tasked with mediating a conflict between Luisa Grimaldi and the new governor general of Brazil, Francisco de Sousa.Footnote 204 Seven months after the pirate attack, Anchieta had left Espírito Santo and traveled north to Bahia to meet the colony's latest bureaucrat. Sousa had arrived in Brazil a year earlier and began taking stock of the Crown's lands, as was his custom. Although Brazil was now formally part of the Habsburg Empire after a succession crisis resulted in Philip II of Spain becoming Philip I of Portugal, the institutions of each kingdom remained largely separate.Footnote 205 The governor general remained responsible for assessing the output of each captaincy and levying taxes as required. Based on Anchieta's letter, it would seem that Francisco de Sousa tried to replace Miguel de Azevedo as captain-major by offering the role to a nephew. It is also likely that he scrutinized Luisa's income and found discrepancies in the amount of tax she owed on the sale of sugar.Footnote 206

The letter states that Anchieta was in possession of a petition from Luisa and Azevedo to receive several undisclosed exemptions from a mandate issued by Sousa. It seems that one was a promise that Sousa would leave men in Espírito Santo in case of another pirate attack, because Sousa had recently been unsuccessful in reaching the hinterlands of Bahia and wanted to recruit more soldiers from the colonies.Footnote 207 Second, Luisa requested formal recognition of her role as governor and confirmation of Azevedo in the office of captain-major.Footnote 208 Anchieta explained that it was quite difficult to get Sousa to agree because he had many reasons to be suspicious of the pair's motives. Those close to Sousa advised Anchieta to listen to the governor general's concerns because he, in effect, had the power to do as he pleased.Footnote 209 Anchieta's strategy proved successful: he was able to confirm that Azevedo was made captain-major for all matters of war in Espírito Santo, and Luisa was granted all her freedoms. He added that a Father Fonseca would take the money she had earned through the sale of sugar to Portugal on her behalf.Footnote 210 Other documents refer to the lost petition written by Luisa, as well as to correspondence between the governadora and the Jesuit.Footnote 211

It is unlikely that Anchieta was acting benevolently in favor of a widow. Other sources suggest that he, in fact, supported the centralization of power in Brazil and an end to the captaincy system.Footnote 212 However, he probably realized that his close relationship with Luisa benefited his current objectives. Anchieta alluded to the dilemma in one of his plays, Na vila de Vitória (In the town of Vitória).Footnote 213 Set during a drought in 1595, the play depicts a moral conflict between Obedience and Ingratitude.Footnote 214 Alfredo Bosi has argued that the play is an allegory for rising tension between the Castilian and Portuguese factions in Espírito Santo. The Iberian Union had resulted in higher numbers of Castilians in the captaincy who had begun to advocate for Vitória to come under the direct authority of the Crown.Footnote 215 The Portuguese, however, resisted calls for the Espírito Santo to become a royal captaincy and sought a special governing statute for Vitória, possibly the petition referenced in Anchieta's letter. Bosi claims that Anchieta took a middle ground that supported the centralization of authority in the captaincy, but that kept Luisa in power.Footnote 216 Anchieta's dilemma is implied through the character of the Town of Vitória, a matronly woman who is torn between obedience to Castile and the platitudes of her husband's heir.Footnote 217

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that Luisa saw the play. In 1594, the Crown's procurator issued a judgment contrary to Francisco de Aguiar Coutinho's legal challenge on 5 September 1594, but this was reversed on 21 November 1594 in favor of the appellant, subject to the latter proving his relationship to Vasco Fernandes Coutinho Filho.Footnote 218 As a result, Luisa decided or was obliged to return to Portugal, where she joined her sisters at a Dominican convent in Évora, taking the name Luisa Grimaldi das Chagas.Footnote 219 Little is known about her life at the convent, but she reappeared in the historical record one last time in 1626, at the age of eighty-five. She deposed in the case of the beatification of José de Anchieta, offering her support in favor of the priest's canonization.Footnote 220

Luisa Grimaldi told the interrogators that she knew Anchieta “very well,” and “liaised with him” when she was in Espírito Santo.Footnote 221 Anchieta was her confessor, and visited her frequently at home while she was the widow of the “captain and governor of Espírito Santo.”Footnote 222 The emphasis on her credentials appears to justify why Anchieta attended to her privately because her companion, Brites de Espírito Santo, a daughter of Miguel de Azevedo who had also traveled to Portugal, did not make the same claim in her deposition.Footnote 223 Like Brites de Albuquerque, who suddenly attracted the interest of the Jesuits once she became governor, Luisa Grimaldi enjoyed spiritual privileges as a result of her authority. Anchieta's attentiveness, therefore, was likely due to the powerful position Luisa held in the captaincy. The document offers little insight into her life or experiences, other than an illness miraculously cured by Anchieta, but its existence and terminology suggest the once-prominent place she had in colonial Espírito Santo.

Luisa Grimaldi only governed for four years, but the surviving accounts of her administration testify to her astute financial and political management. Fernão Cardim wrote that Espírito Santo in 1590 was rich with cattle and cotton, six sugar mills, many cedar plantations, and tall trees.Footnote 224 Vitória had also more than 150 settlers, considerably fewer than Olinda or Santos, but it was enough to attract the Castilian colonists who demanded centralization.Footnote 225 Her efforts to expand missionary activity were met with enthusiastic support and collaboration, particularly by José de Anchieta. Her friendship with the Jesuit was vital to her continued independence in Espírito Santo, and she leveraged her wealth and privileges as governor to ensure that Anchieta remained supportive. Based on the original judgment in her favor, it does not appear that she wanted to return to Portugal. While it is difficult to determine her intent, her efforts to have her authority recognized by the governor general in 1591 suggest that she was committed to governing the captaincy of her late husband and remaining in a town where she had spent almost twenty years.

CONCLUSION

In this essay, I have argued that women like Ana, Luisa, and Brites were important imperial agents who contributed to the early colonization of Brazil in the sixteenth century, especially through land donation. These women were empowered by the rights and obligations conferred by the donation charter and the foral to their husbands and they shared this power with their lieutenants (sometimes called captain-majors or governors), the municipal councils of each township, and the judiciary. Property ownership was at the heart of power, and women who managed hereditary captaincies had control over land distribution and, often, the profits of their families’ plantations. As a result, contemporaries kept detailed records of land donations because the legitimate exercise of these administrative privileges and obligations became relevant in land disputes. In these records, Brites de Albuquerque and Luisa Grimaldi were called governadoras and capitoas (woman governors and woman captains), while Ana Pimentel was her husband's procuradora (woman procurator) because he was still alive at the time of her mandate in São Vicente, although she was also called donatária (woman donatary). It is not clear when women became capitoas, but it seems to be based on the absence of a male heir.

Analyzing the impact of each woman's responsibilities and decision-making sheds important light on their active role in the colonization of Brazil. There is a tendency to categorize women as submissive in accounts of colonial Brazil based on the laws and social codes that restricted their movement, rights, and agency in ways that varied according to race and class.Footnote 226 However, the evidence presented in this essay reveals that the imperial project did not completely exclude women from legally exercising authority. White women married to colonial captains were in a position to assert authority through rights and obligations endowed to the patriarch and inherited by his descendants, where royal intervention or social practice enabled such inheritances. When he or his descendant was unable to govern, his spouse was the logical interim authority due to the fidelity imputed to kinswomen. It was in their best interests to protect the patrimony, which, in the context of colonial Brazil, involved administration in growing the captaincy's economic output through settlement, slavery, and catechism.

Through a critical reading of administrative documents, letters, plays, travel diaries, and chronicles, this essay has argued that Ana Pimentel, Brites de Albuquerque, and Luisa Grimaldi carved out a significant space in colonial government and were supported by other elite women, like Catherina of Austria, in the metropole.Footnote 227 Contemporaries meticulously recorded the authority attributed to donataries’ wives to protect their land rights, while missionary orders relied on the wealth and influence of these governadoras to construct the first aldeias, Jesuit colleges, and hermitages. They did so under the influence of European gender norms, which cast women as passive bystanders or virile Amazons, or, at times, ignored their presence altogether. Nevertheless, their interactions with Ana, Brites, Luisa, and even Inês show that colonization was not completely male in sixteenth-century Portuguese America. At times, women were decision-makers in matters of land distribution, slave raids, and fiscal policy. It was the gendered modes in which contemporaries presented these women that have, until now, obscured the degree of agency they wielded.

***

Jessica O'Leary is a Research Fellow at the Australian Catholic University. She is a gender and cultural historian of the early modern period, interested in global history and connections between people around the world.