INTRODUCTION: MATERIAL TRANSLATION AND EKPHRASTIC FAILURE

At the meeting of the Royal Society of London on 8 October 1662, it was “ordered that the Thanks of the Society be given to Dr Merrett for his paines in translating the Italian discourse de Arte Vitraria, upon the Motion and desire of the Society.”Footnote 1 The text worthy of praise, The art of glass,Footnote 2 was a significantly expanded English rendering of L'arte vetraria, a recipe manual, or book of secrets, compiled by Antonio Neri (1576–1614) and published in Florence in 1612.Footnote 3 Neri's translator, Christopher Merret, MD (1614–95), counted among the society's charter members.Footnote 4 Well connected with London's virtuosi, he was an avid botanist, keen natural philosopher,Footnote 5 and from 1654, first keeper of the Harveian collection at the Royal College of Physicians, where he had been a fellow since 1651.Footnote 6

In preparing The art of glass, Merret had opportunity to exercise his wide-ranging curiosity. The 147 pages of “Observations” he appended to Neri's recipes testify to his having assumed the roles of bibliographer, commentator, experimenter, and confidant, all in an effort to make not just Neri's Italian but also his artisanal knowledge accessible to the society.Footnote 7 Merret took additional “paines” as a field collector and curator, assembling a cache of materials relevant to glassmaking.Footnote 8 These objects, integral to the interpretive project that bore The art of glass, later mediated the book's reception. That Merret amassed a physical archive did not escape the attention of his first readers. By October 22, the fellows desired that he “bring in his Materia Vitraria, spoken of in the booke he hath lately translated out of Italian into English.”Footnote 9 One imagines that, as custodian of the Harveian collection, Merret well understood the role objects played in the acquisition of knowledge.Footnote 10 He certainly proved responsive to the call for an exhibition of his sources. Just two meetings later, on November 5, he “shewd the Society his Materia Vitraria: for which he received their thanks, being desired, to leave a part of each of the materials with the Society.”Footnote 11

Merret's collection of vitreous matter is now lost or dispersed.Footnote 12 This article sheds new light on its contents. Drawing from institutional records, personal correspondence, extant catalogues, and The art of glass itself, I recover a partial inventory of materials relevant to glassmaking that passed into Merret's hands and would in turn draw the scrutiny of his peers and later readers at the Royal Society. I show how these objects—raw ingredients, waste products, vessel fragments, archaeological finds—extended Merret's “Observations” on Neri's text. They participated first as corroborating illustration, then as material refutation, in what Sven Dupré calls the palimpsestic “codification of error” endemic to the translation of artisanal knowledge.Footnote 13

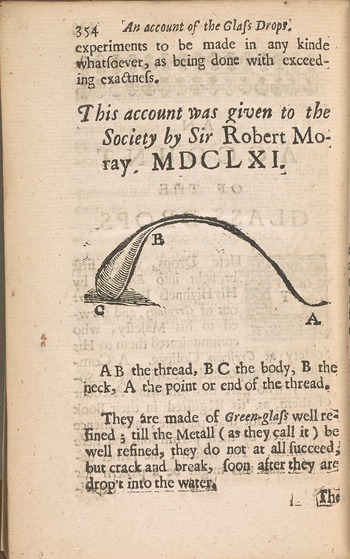

Merret's object appendix manifests the “ekphrastic failure” of an otherwise ungraspable textual project.Footnote 14 The English physician found Neri's written descriptions of glass and its making insufficient to delineate what he knew—based on firsthand observation and the testimonies of craftsmenFootnote 15—to be a visual and manual art, to say nothing of an aural and gustatory one.Footnote 16 Graphic representation proved similarly inadequate. The art of glass lacks figures save for a single woodcut of a glass drop (fig. 1), an image that doubly illustrates the defiance of vitreousness in yielding to the black-and-white linear grammar of the print medium.Footnote 17 Not even diagrams of furnaces or scenes of laboring craftsmen punctuate the text as they do Giorgio Agricola's De Re Metallica (On the nature of metals, 1556), one source for Merret's commentary.Footnote 18 Only the materia vitraria, the things of the trade themselves, had eloquence enough to render glass and its making present before readers at the society.

Figure 1. Antonio Neri. The art of glass. Trans. Christopher Merret. London, 1662, page 354. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Merret's collection contributes an instructive case study to a growing body of scholarship that demonstrates the limitations of early modern texts in conveying material properties and craft processes.Footnote 19 To this end, historians have increasingly construed reading as an embodied practice extending well beyond the page.Footnote 20 For Merret, the process of translating L'arte vetraria involved not just comprehending Neri's Italian and rendering it into English as best he could,Footnote 21 but also gathering objects, information, and vocabulary from artisans across London.Footnote 22 Such an assemblage of matter and practical knowledge allowed him, as Lorraine Daston puts it, to “re-experience the process of writing the work.”Footnote 23 Merret in a sense re-staged the interactions with Venetian glassmakers that had informed Neri's work at the Medici court fifty years prior—even if the English physician did not always find it necessary to extend his reenactment to testing the recipes Neri himself recorded.Footnote 24 Fellows at the Royal Society in turn required that a close reading of the translated text involve their equally close proximity to the source material on which the author drew: truly grasping the contents of The art of glass would entail handling Merret's collection.Footnote 25

Elusive as the materia vitraria remain, recent scholarship on The art of glass has centered not on this lacuna in today's archive but rather on what Merret himself lacked access to in the seventeenth century: malleable glass, a “storied object” of ancient legend debated among antiquaries, chymists, physicians, and natural philosophers.Footnote 26 In an account of malleable glass as both prestigious deperdita (lost objects) and subject of reconstruction in the Royal Society's circle, Vera Keller draws particular attention to Merret's doubt about the existence of such a ductile material.Footnote 27 The present article complements Keller's work at conjuring absence. And while I focus on early modern materia instead of ancient deperdita, my study is no less engaged with the Roman world, albeit its northern reaches. I show how the fellows’ pursuit of late classical archaeology fed into and came to be informed by their shared familiarity with Merret's text. The circulation among virtuosi of Roman shards excavated in Restoration England speaks to the role that an antiquity at once tangible and local played in the late seventeenth-century study of glass at the society.

Yet the fellows’ initial interest in L'arte vetraria stemmed not from their regard for ancient wares or even, for that matter, from their engagement with the alchemical tradition in which scholars tend to locate both Neri's recipes and Merret's commentary.Footnote 28 A larger aim of this article is to reassess the place of the 1662 translation within the society's history of trades program, a Baconian initiative Merret went on to chair from 1664.Footnote 29 As I demonstrate, those virtuosi in Merret's London circle who encouraged his efforts sought to develop English glass manufacture by finding cheaper, local sources for foreign ingredients listed in Neri. I argue that the materia vitraria reified their shared concern with the development of domestic industry.

The art of glass has been held up as an exceptional successFootnote 30 within the context of the fellows’ otherwise failed attempts to document contemporary trades.Footnote 31 Along with Walter Charleton's Mysterie of the vintners (1667), it was one of only two monographic histories to result from the program.Footnote 32 Kathleen Ochs argues that the singularity of these works can be attributed to the individual efforts of their authors (Merret's “skill and perseverance”Footnote 33) and not, rather, to what she calls the “auxiliary programmes” that supported the larger project, such as the endeavor to organize the society's repository.Footnote 34 Ochs goes so far as to claim, “Collective experiments and collection of natural histories . . . contributed little because, although the history of trades programme was designed to be a cooperative project, little corporate work was completed.”Footnote 35

As the exhibition and acquisition of materia vitraria make clear, however, not just translating, but also reading and revising The art of glass, were remarkably collective enterprises. Merret relied on cooperative endeavor—namely, note-taking in the “field”Footnote 36—as much as the readers of his text who depended on the consultation of samples as a group for their understanding and improvement of it. International networks were also a vital source of information on the glass trade, dispatching materials relevant to glassmaking that enacted a physical translatio, or movement of knowledge, from one place to another.Footnote 37 The institutional records and personal letters I cite below attest to the myriad glass shards, waste products, and raw ingredients that reached England from the Continent, often serving as points of comparison for local industry. Here, as elsewhere in the early modern period, the respublica litteraria functioned both as a network of correspondence per se and as a system of connected channels through which objects passed, on loan or as gifts, for the purpose of collective scrutiny.Footnote 38

What emerges from the present article, then, is a picture of collaboration and crowd-sourcing at the early Royal Society not unlike that which Deborah Harkness captures in her lively account of experts, practitioners, and go-betweens doing “Big Science” in Elizabethan London.Footnote 39 But glassmaking had come a long way since the days when William Cecil (1520–98) visited furnaces outside Aldgate or Cripplegate.Footnote 40 Before turning to Merret and his milieu, I will briefly summarize the seventeenth-century development of the industry, the better to locate The art of glass in its wider economic landscape.

GLASS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND

Scholars generally split the history of seventeenth-century English glassmaking into two distinct chapters.Footnote 41 The first chronicles the shift, beginning in the 1610s, from wood-fueled to coal-fired furnaces.Footnote 42 What followed was the rise of a patent-protected monopoly, centered in London and Newcastle, that saw naval administrator-turned-entrepreneur Sir Robert Mansell (1570/71–1652) exploit the technical expertise of migrant workers—many of them transplants from France, the Low Countries, and Northern ItalyFootnote 43—in pursuit of quality crystal glass.Footnote 44

As the winds of conflict began to sweep through the British Isles, Mansell lost what control he exerted over the sector. In 1640, Scotland's victory in the Bishops’ Wars rattled production at his Newcastle glassworks; the skirmish at Newburn also cut off a vital coal supply to his London furnaces.Footnote 45 Two years later, in June 1642, Parliament finally stripped him of his almost thirty-year monopoly.Footnote 46 Despite these setbacks, Mansell continued to operate Tyneside for at least a decade longer.Footnote 47 It is thus his death, rather than the cessation of his monopoly as such, that some scholars view as having precipitated a renewal of interest in the English glass trade—a zeal arguably reflected in the society's eagerness for a translation of Neri.Footnote 48

Yet histories of the trade all but skip over the Interregnum, instead picking up after the Civil War with the resumption of patent grants at the later Stuart court; the consolidation of plate and vessel production under George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham (1628–87); the charter of the Company of Glass Sellers in 1664; and the increased protectionism for which this body lobbied to stave off competition from Venice.Footnote 49 The denouement comes in 1674 or thereabouts when English furnaces, again reliant on foreign workers, succeed in manufacturing colorless lead crystal (called “flint glass”)—a process patented, and later tweaked, by the London merchant George Ravenscroft (1632–83).Footnote 50

Did Merret's text provide the impetus for Ravenscroft's venture?Footnote 51 Considering the state of the trade in 1662, Merret famously remarked, “glass of lead, ’tis a thing unpractised in our furnaces”;Footnote 52 by 1670, Ravenscroft's workmen were experimenting with recipes for “crystalline glass resembling rock-crystal.”Footnote 53 Ravenscroft himself was no craftsmen, surely not the chymist-inventor scholars once assumed him to be, so the fact that he could access Neri's recipes in the vernacular likely mattered little to batch production at his furnaces. He was, however, a canny and persistent entrepreneur who, if he read Merret's commentary, must have sensed a business opportunity.Footnote 54 And indeed, Ravenscroft's purported invention—a long-sought-after domestic rival to Venetian cristallo (transparent glass that resembled rock crystal)—revitalized the London industry.Footnote 55

The bifurcated history of seventeenth-century glass I have just outlined reduces the late 1640s and 1650s—the period of Merret and his circle's initial interest in the substance—to a mere postscript or prelude. To the extent that scholars of glass treat the Commonwealth era, they dismiss it as a time of contraction in domestic production.Footnote 56 Eleanor Smith Godfrey does suggest that the quality of English crystal glass, if not its quantity, improved during the Interregnum.Footnote 57 Her account of the industry stops short of the Civil War, however. Of Merret, she notes in passing, “Though [he] wrote the commentary in 1662, his knowledge of glassmaking methods went back at least to the 1640s when he was associated with experimentation at Gresham College.”Footnote 58

Picking up where Godfrey leaves off, I reconstruct a backstory to Merret's text that fills a gap in the broader literature on the development of English glass. By engaging with documentary sources from outside the industry rather than with the patents or rate books to which economic historians usually turn, I approach glass as it was experienced in the hands of those men—whether virtuosi, physicians, craftsmen, or natural philosophers—who bartered, gifted, created, and studied it. Complementing the well-told tales of Mansell's monopoly, Buckingham's privilege, and Ravenscroft's patent, my account of Merret's translation project, and of the subsequent collection of materia vitraria in the milieu of the early Royal Society, offers a microhistory of glass as both industrial commodity and tangible curiosity in early modern London.

GLASS AND THE HARTLIB CIRCLE

Neri opens his 1612 treatise with a dedication to his patron, “the most Illustrious and Excellent Lord Don Antonio Medici.”Footnote 59 Though Merret chose to include this citation in his translation, he follows it with an address to a contemporary, “the Honourable, and true Promoter of all solid Learning, Robert Boyle, Esq.”Footnote 60 Merret credits Boyle (1627–91) as “the principal cause that this Book is made publick, by proposing and urging my undertaking of it, till it came to a command from that most Noble Society . . . meeting at Gresham College, whose desire I neither could nor ought to decline.”Footnote 61 No documents survive detailing the proposal, but Boyle is thought to have encouraged Merret to begin work prior to the society's founding in 1660.Footnote 62 He was not the only one. Another figure in Merret's London milieu, Samuel Hartlib (ca. 1600–62), comes across on paper as an even stronger advocate for the project than Boyle.Footnote 63 Hartlib suffered a stroke in late 1660 and did not live to see The art of glass through to publication.Footnote 64 He did, however, have opportunity to make Merret's acquaintance, a meeting he records in his extant notebooks, the Ephemerides.Footnote 65 It is to Hartlib's interest in the manufacture of glass—a curiosity shared by many in his circle—that I will now turn.

Mechanica in the “Ephemerides”

During the Interregnum, Hartlib, along with Boyle and John Evelyn (1620–1706), championed a Baconian history of trades program.Footnote 66 Hartlib couched his support for the project in Protestant notions of reform and the improvement of mankind.Footnote 67 He was more concerned with the practical, immediate outcomes of disseminating knowledge through written histories than he was with the theoretical underpinnings of technological innovation, an objective more in line with Boyle's philosophical tendencies.Footnote 68 In 1650, Hartlib in his notebook singles out Merret, listed as “Dr Merrick,” for his involvement in the enterprise: “There is a Company or Society Dr Whustler Dr Merrick / That have promised to make a Club for the perfecting of Mechanical Arts and to meete and correspond with Mr Worsley about it.”Footnote 69

A year earlier, Hartlib had identified Merret as having Neri's work in his possession. Observing that “they are yet very defective of making Glasse in England,” he notes, “There is an excellent little Treatise in Italian which Dr Merrick as I take it is said to have De Arte Vitraria which if it were translated would bee a booke only of 3. or 6. d. price.”Footnote 70 Hartlib evidently wanted to flag L'arte vetraria as potentially contributive to the trades project: in the tabular index for the entry, he jots down “Trades” alongside “Glasses” and “Libri selecti.” He uses the first of these marginal pointers (“Trades”) alongside “Mechanica” throughout his notebooks whenever he categorizes information relevant to what Bacon called the “diverse Mechanicall Arts.”Footnote 71

Seven years later, in May 1656, Hartlib returned to the “Art of glasse making” in the Ephemerides. Recording a copy of Neri's treatise now in Boyle's custody, he insists once more on the necessity of a translation: “Mr Boyle hath a very rare Booke in Italian . . . De Arte Vitraria which should be Englished or Epitomized.”Footnote 72 Hartlib's appeal to the vernacular here is consistent with his pragmatic vision for the trades project as a whole. The implied audience of non-Latinate readers also stands in contrast to the more learned market to which the Dutch publisher and bookseller Andreas Frisius (1630–75) later sought to cater with his own Latin translation of Neri-Merret, published in Amsterdam in 1668.Footnote 73

As Hartlib's notes indicate, the first Italian edition of L'arte vetraria was rendered doubly inaccessible to London virtuosi by the small number of copies circulating in England. Not long after its printing in 1612, the treatise fell “into oblivion” in Italy and by extension the rest of Europe.Footnote 74 Merret himself counts the rarity of the book as a motivating factor for his translation, even more so than its language.Footnote 75 In his dedicatory remarks, he claims to have “satisfied [Boyle's] vast desire of communicating knowledge to others, who though intelligent of the Language could not procure Copies in the Original.”Footnote 76

The mid-century scarcity of copies can be attributed to the fact that no further edition was prepared in Italian until the Florentine printer Marco Rabbuiati reissued Neri's text in 1661, “corrected and expurgated of various mistakes.”Footnote 77 A Venetian edition followed in 1663, with a second printing in 1678, by which point Merret's augmented English version was already in wide circulation.Footnote 78 The recipe palimpsest received a further translation into German at the hands of chymist Johann Kunckel von Löwenstern (1630–1703), who, having compared the Latin and Italian editions, added some improvements of his own, which he published in 1679.Footnote 79

“Learn't in the Glasse-house”

Hartlib's notebooks help elucidate the demand-side impetus for Merret's translation. If one looks beyond Hartlib's citations of The art of glass in particular and to his documented interest in glass and glassmaking in general, a fuller picture emerges of a voracious Interregnum virtuoso culture where samples, raw ingredients, waste products, and artisanal knowledge were both highly sought after and collectively gathered.Footnote 80 Against this background, Merret's work can be viewed as one contribution to an ongoing, proto-institutional endeavor to understand the material properties of glass at a time when newly developing relationships between craftsmen and virtuosi led to the gradual revelation of what had previously been regarded—and withheld under the dictates of patent or privilege—as workshop secrets.Footnote 81

As is well known, Hartlib's Ephemerides are rich with evidence of the mid-seventeenth-century exchange in craft knowledge.Footnote 82 Hartlib's interests in artisanal trades were wide ranging, and his preoccupation with glassmaking complemented a related curiosity about optics and the advancement of optical devices, much of which hinged on the quality of the glass (or its surrogates, mica and rock crystal) employed in instrumentation.Footnote 83 In 1659, he wrote to Boyle to request “some piece of glass, good and fine” in the hope that he might use it to barter with the French mechanician Étienne de Villebressieu (1626–59) for a reciprocal fragment of the craftsman's as yet proprietary optical workmanship.Footnote 84 Hartlib's notebooks also reflect his solicitation of expertise from jewelers and painters regarding several additional topics covered in Neri, such as the composition of pigments and the translucence of gems.Footnote 85

For information on glassmaking specifically, Hartlib relied on an enterprising foreigner with Continental connections, Johann Brün (or Unmussig) (fl. 1648–68).Footnote 86 From the late sixteenth century onward, English glasshouses had seen an influx of workmen from France and the Low Countries. Hartlib singles out Brün—also a confidant of Boyle—for his network. He cites his friend's knowledge as having been “learn't in the Glasse-house in London” and goes on to recount how “The men in the Glass-house told Mr Unmussig of a Glasse.”Footnote 87 Among the contributions from Brün that Hartlib files away is a description of “Solda / in Italian et Latin,” an “herbe brought out of Spaine being made or burn't into powder . . . the chiefe ingredient that makes glasse so cleere <and fine>. The Venetians keepe the best matter to themselves and send the worst abroad.”Footnote 88 Hartlib categorizes this information under the headings “Mechanica” and “Glasse making,” the same designations he later uses in reference to Neri's treatise.Footnote 89

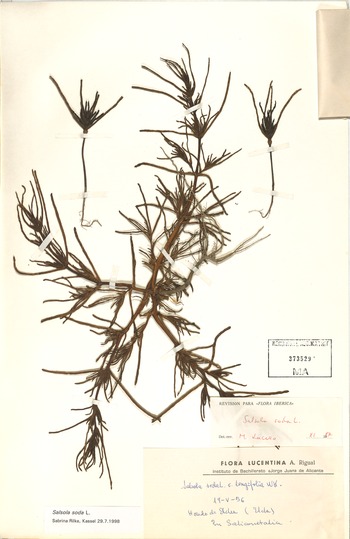

Is this a first clue to an entry in Merret's materia vitraria? Hartlib's note refers to Salsola soda (glasswort or opposite-leaved saltwort) (fig. 2), a halophytic marine plant native to the Iberian Peninsula and wider Mediterranean basin that, when burned, yields an alkaline residue known as barilla.Footnote 90 The Venetians had begun importing burnt Salsola soda from Spain in the sixteenth century, thereafter controlling its trade. As Brün's confidants well knew, glassmakers in Murano were forbidden from exporting the plant's ashes to Northern European centers like Antwerp or London, cities where immigrant workers—many of them native to the Lagoon—had introduced sodic glassmaking (façon-de-Venise) to an industry otherwise dependent on wood-ash.Footnote 91

Figure 2. Salsola soda (family Chenopodiaceae) from Alicante, Spain. Herbario del Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC. MA 00373529. © RJB-CSIC.

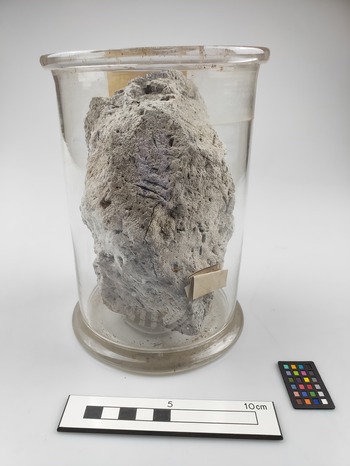

By the early seventeenth century, though, some quantity of Spanish ash had, like Neri's recipe book, made its way to England (fig. 3).Footnote 92 In 1620—three decades prior to Hartlib's note—the mercantile agent James Howell (ca. 1594–1666) wrote home to London from Alicante describing his purchase there of a “commodity called barilla . . . for making of crystal glass,” a parcel of which he acquired from a Genoese merchant to “send . . . to Sir Robert Mansell.”Footnote 93 Howell in his letter records that “the Venetians have it hence,” and he proceeds to devote several sentences to the growth pattern, flowering, drying, and pit burning of this “strange kind of vegetable.”Footnote 94 Even with limited access to the finest barilla, though, Mansell's London furnaces failed to produce genuine Venetian crystal.Footnote 95 One must assume that whatever alkali salts the workmen extracted from the Valencian plant-ash did not match the purity of sale de cristallo (crystal salts) prepared in the Veneto.Footnote 96 The failure to translate the proprietary Muranese purification process to London furnaces would have made Neri's treatise all the more valuable on the English market. L'arte vetraria opens by disclosing a “new and secret way” to pulverize and purify barilla, a process Merret renders as “the foundation of the Art of Glasswork.”Footnote 97

Figure 3. Barilla, donor J. W. Cumming. Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Cat. no. 45959.

Did a sample of burnt “solda” make its way into Hartlib's hands as well as Howell's, and later into the society's collection? Judging by Merret's note-taking in the field, the variant sources of sodic ash used in the Venetian industry remained a point of confusion to at least some London workmen at mid-century. Commenting on book 1 of L'arte vetraria, Merret writes that “Rochetta”—the term Neri uses for the ashes of eastern Mediterranean halophytes, inferior to Spanish varieties—was a name “wholly unknown to our Glass-houses.”Footnote 98

The Search for Domestic Materials

The shift in English glassmaking from wood-fired to coal-fueled furnaces spurred the quest for sodic ash that took Howell to Alicante. Previously, workers in need of potash could burn the same trees they relied on for fuel (e.g., beech or oak).Footnote 99 With the deforestation of the Weald and the introduction of the coal process, however, merchants and makers had to look beyond brushwood for their alkalis. One alternative source, kelp, grew on rocks in the northern reaches of the British Isles, where it also washed ashore. By 1621, the Scottish glassworker James Ord had moved to secure the exclusive rights to prepare its ashes in Scotland.Footnote 100

Surveying the glass-ingredients trade from London three decades hence, Hartlib became increasingly interested in how the exploitation of yet more domestic resources could advance manufacture in England.Footnote 101 In a notebook entry from 1653, he touches upon the three main components of a glass batch: alkalis, sand, and cullet. He lists in turn, “Potashes / Colonel Wurtz promised to write downe the whole mysterie of making of Potashes”; “Glittering Sand, Glasse / Greene or white glasse beaten smal into Powder gives an excellent glittering sand. Also by it something may bee gained, they selling ordinary sand for 2 d. a pound”; and “Glasse broken / Broken glasse remelted makes a more excellent kind of glasse then before.”Footnote 102 These last two entries demonstrate Hartlib's familiarity with a raw-materials market that extended beyond the shipment of sodic halophytes from Spain or seaweed from Scotland.Footnote 103 His comments on pulverization and reheating suggest that he was especially attuned to the glass recycling economy.Footnote 104 Hartlib's tradesmanlike regard for cullet as a commodity may in turn have informed the tastes of those in his circle who came to valorize shards.Footnote 105 The fellows in receipt of Merret's materia vitraria learned to look upon broken glass, as well as potash and sand,Footnote 106 with a covetousness equal to that which Continental princes extended to the cristallo vessels they housed in courtly cabinets.Footnote 107

What Colonel Wurtz divulged the Ephemerides do not reveal. In 1654, though, Hartlib, still on the hunt for viable alkalis, came across a contemporary whose knowledge of potash derived from Poland, where glassworkers followed the recipes of metalworker Johann Rudolf Glauber (1604–70).Footnote 108 Two years later, an encounter with yet another foreigner familiar with Glauber's preparations led Hartlib to reiterate his faith that an ash capable of producing quality sodic vessels might yet be leached from English plants.Footnote 109 To Hartlib, “out-glassing” the Venetian competition was—like the development of steelworking he references earlier in his notebooks—a matter of locating and extracting natural resources previously unexploited in the British Isles.Footnote 110

“Some advantage to our Countrey-men”

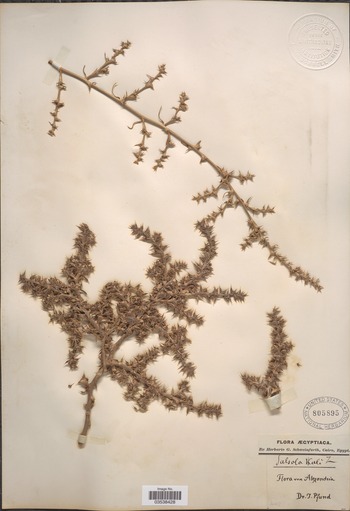

Merret appears to have imbibed Hartlib's nativist economic position. In the introduction to The art of glass, he hazards, “I doubt not but [the book] ‘twill give some light and advantage to our Countrey-men of that profession [glass making], which was my principal aim.”Footnote 111 Such a Hartlibian objective surely motivated the expansive approach he adopted to the translation of Neri's work: contributing to the growth of domestic industry meant not only publicizing Italian recipes but also lessening the reliance of English furnaces on imported ingredients, many of them of dubious quality.Footnote 112 Arriving at vernacular raw materials was, like translating an Italian term of art, far from straightforward.Footnote 113 Neri in the first book of his treatise lists various sources for alkaline ash, which Merret elaborates upon in an extended gloss. He cites the botanist William Turner (d. 1568) in remarking that the Kali plant (fig. 4)—Salsosa kali, whose finely ground sodic ashes Neri terms polverine—“hath no name in English, and though it be very plenteous in many places of England, yet I could never meet with any man that knew it.”Footnote 114 He goes on to caution based on “an experiment made at the Glass-house” that while “our river Thames, and Sea-coasts, affords [two sorts of Kali] in great plenty . . . ours will not make ashes for Crystall, or any other sort of Glass.” Merret concludes that the plant is as yet better sourced from the Levant, noting that its “saltish” ashes could be purified to yield a strong white alkali.Footnote 115

Figure 4. Salsola kali (family Chenopodiaceae) from Alexandria, Egypt. Smithsonian Institute. Cat. no. 805895.

Merret clearly sought out examples for his materia vitraria of both efficacious Mediterranean alkalis and their unsuccessful English alternatives. He makes explicit reference to having “seen” and “had by him” a sample “taken from their Polverine bags call'd Kali spinosum by the Herbarists.”Footnote 116 Of the plants themselves, Merret goes on to observe that “our Kali when gathered appears to the tast very brackish and salt, and will being laid in moisture, contract it self into a small dimension.”Footnote 117 Physical inspection of these plant samples and prepared salts would have made the distinctions drawn in the text between local and foreign varieties of Kali all the more vivid to Boyle and company. Merret's 1662 performance of his collection may well have included a taste test of any alkalis presented.Footnote 118 He evidently cultivated gustatory discernment as part of his research. Elsewhere in The art of glass, he shares with the reader that “in old windows of French glass . . . you may manifestly discern, nay, pick out pieces of salt, easily discovering their nature to the tast.”Footnote 119

Merret's observations on the paucity of English equivalents for foreign sources of sodic ash anticipate what was to become a tired refrain for the history of trades program. The fellows repeatedly found geographic conditions to be among those “diverse circumstances” that complicated their attempts to improve native industry using overseas models or translated texts.Footnote 120 Undeterred, Merret looked to another English trade, the “Button-mold-makers,” for local knowledge that could be brought to bear when sourcing components for a glass batch. From these men he learned “how much . . . the seasons of the year difference Vegetables.”Footnote 121 No wonder Merret went on to chair the trades project at the Royal Society. That he cites mold-makers in his commentary as readily as he does glassworkers or refiners accords with Aaron Mauck's claim that to Merret, “virtually any trade could lead to improvements in natural knowledge.”Footnote 122

Merret met with more success as a field collector in England when he looked beyond halophytes for a source of alkaline ash.Footnote 123 Of potash derived from firs and pines, he first identifies “Poland, and Russia, and New-England” as points of origin. He goes on to describe these and other wood-ashes as easily mixed up on the domestic market: “For Green-glasses in England, they buy all sorts of ashes confused one with another, of persons who go up and down the Countrey to most parts of England to buy them.”Footnote 124 Surveying the options within the British Isles, he then contends that “the best and strongest of all English ashes, are made of the common way Thistle, though all thistles serve well to this purpose.”Footnote 125 For other sources of alkali salts, he suggests “Leguminous plants,” noting that “Lentils . . . lately sown plentifully in Oxford-shire” have “been found by experience good to this effect.”Footnote 126 English oak, ash, and hawthorn trees are also listed as “communicating in their Salts” when burnt.

Merret sought to provide additional information on domestic natural resources useful in coloring glass. His comments on Neri's recipes for achieving tincture concern metals mined locally. Take, for example, manganese, which, as a monoxide (MnO), gives a pink or purplish tint; manganese dioxide (MnO2), on the other hand, serves as a decolorizer, acting on the iron found in siliceous sand to yield practically colorless glass.Footnote 127 Though Neri insists on the Northern Italian region of Piedmont as the best source for manganese, Merret claims “some few years since, the industry of our nation hath found in our own countrey at Mendip-hills (famous for Lead) in Somerset-shire, as good as any used at Moran.”Footnote 128 Of Lapis calaminaris (in the seventeenth century meaning zinc oxide, the ore of zinc and a component of brass, also used to color glass), Merret locates a source “in Sommersetshire, and the North of Wales” that he considers superior to Polish imports: “though some of it hath been brought from Dantzick, yet ’tis not of the same goodness with ours of England.”Footnote 129 A few pages later, Merret reports on another domestic source of zinc ore, indeed a recent find: he observes that large stones of Calcarii, used in the manufacture of brass, were “formerly brought from Holland, but have been sometimes since found in the mountanous parts of Cornwall.”Footnote 130

On the subject of tincture, Merret was also cognizant that the slightest impurities (iron) in sand could impart a green hue to a batch of glass. He introduces for his readers’ benefit three criteria—color, grain type, and size—with which to distinguish grains used for clear façon-de-Venise vessels from more ferruginous sands constitutive of green-glass bottles.Footnote 131 He writes, “Our Glass Houses in London have a very fine white sand (the very same that's used for Sand-boxes and scouring) from Maid-stone in Kent, and for Greenglasses, a coarser from Woolwich,” which he describes as “harder and more gritty.”Footnote 132 The distinction would have been all the more clear if performed at the Royal Society as part of the multisensory display of materia vitraria. Again, samples could well have ended up in fellows’ mouths: when Merret elsewhere discusses sand as a possible component of zaffer (a cobalt compound), he assures his reader that “your tongue and teeth may easily discover it.”Footnote 133

At least one reader sought to experience the fineness of a Kent grain for himself. In the 1681 catalogue of the Royal Society's repository prepared by Nehemiah Grew (1641–1712), there appears among the “Earths” a donation from a “Mr. Evelyn” of “FINE SAND, from a Sand-Pit near Bruley in Kent.”Footnote 134 Grew notes, “Of this is made the clearest and best English Glass” (fig. 5). With this entry in mind, I will turn to consider the collection and trade of materia vitraria in the society's milieu subsequent to Merret's translation.

Figure 5. Nehemiah Grew. Musaeum Regalis Societatis; or a catalogue & description of the natural and artificial rarities belonging to the Royal Society and preserved at Gresham College. London, 1681, page 346. © The Royal Society.

THE REPUBLIC OF GLASS AND LETTERS

The exhibition of natural and artificial curiosities was a frequent event at the meetings of the early Royal Society.Footnote 135 Grew's descriptive catalogue of the institution's repository attests to the variety of rarities acquired, with many items having been sent to fellows from afar.Footnote 136 Hartlib had previously espoused that collectors in his circle cast a wide geographic net for “didactica.” In his notebooks, he recommends that those traveling to the “Oriente . . . should bee instructed what to observe and collect not only Book's and MS but likewise the History of Nature and Art.”Footnote 137

Following the publication of The art of glass, fellows venturing to the Continent, if not the “Oriente,” seized the opportunity to collect samples of vitreous matter. The dispatch of these materials afforded members of the Royal Society a more holistic picture of the glass trade as it was practiced abroad. What evidence of contemporary manufacture they accumulated complemented the firsthand experience of London workshops one finds recorded in Hartlib's notebooks or Merret's commentary.

Oldenburg as Collector and Correspondent

The correspondence of Henry Oldenburg (ca. 1619–77), the society's first secretary, reveals channels whereby information on glass manufacture and materia vitraria reached England.Footnote 138 When in 1666 Oldenburg wrote from London to Johann Hevelius (1611–87), a consul in Danzig, he included a list of “annexed queries” sent on behalf of the fellows. From Hevelius he sought “in all parts those things with which Nature enriches different regions.”Footnote 139 Among his questions was whether “Signior Burattini” (Tito Livio Burattini [1617–81]), the master of the mint to the king of Poland, had “the Art (as has been written from Paris) to make such Glass, as is not at all inferior to Venice-glass, and exceeds any plate of Glass, hitherto made there, twice or thrice in bigness?”Footnote 140 Taking after Hartlib, Oldenburg probed Hevelius for details: “What is the way of making Pot-ashes in Poland?”Footnote 141

Other of Oldenburg's letters attest to his correspondents’ successful extraction of samples from European glasshouses. In August of 1668, Samuel Colepresse (d. 1669) of Devon, then stationed in the Netherlands, wrote to Oldenburg of opal glass, recalling its accidental manufacture at the Duke's Glasshouse in Woolwich, England.Footnote 142 He compared the chance incident at the English workshop with the more calculated preparation of the substance at Haarlem, where he recently observed “the experiement of this soe livelie-counterfeited Opall in Glass for wch. they now have their certain Rules.”Footnote 143 Colepresse went on to explain the role of heat in yielding variant opacities of the substance. He assured Oldenburg that he had acquired “ye Specimina of the severall degrees: wch. with some curiositie & wonder I observed in ye operation.”

The interest of both men in the opaque substance persisted, and on November 20, Colepresse again wrote to Oldenburg, this time including the aforementioned evidence: “You'le find herein (according to order) inclosed: I have added 4 little peices to it, all of ye very same mettall, & out of ye same pot, with ye great peice,* . . . I likewise adde, a peice of ye Red-glass, thoe not soe well mixt, as wisht, or probablie may on a second tryall: another peice shows you ye sedement of ye Red composition. . . . I shall let slip noe oportunitie of gaineing what glass-specimena & informations I can from ym; nor of sending ym you.”Footnote 144

Colepresse intended these imperfect samples not just as proof of the impact that variant heating and cooling methods had on opacity, but also as material testimony to his firsthand observation of the glassmaking process. In his gloss, he avows, “I was present at ye furnace ye [time] these peices of glass, I now send you were taken out, & diverslie cool'd. . . . I adde a fifth, wch. I had forgott, wherein lies ye greatest degree heat, & opacitie.”Footnote 145 By the end of 1668, Oldenburg had received yet more samples from his man in the Netherlands. Writing from Leiden on December 14, Colepresse relates that “my Glass-Correspondent . . . has sent me a few specimena of their Glass-experiments, wch I carefully transmitt you.”Footnote 146

Framing Glass in Archaeology's Window

A similar practice of attaching samples to correspondence transpired in domestic mail, and the fellows augmented Merret's materia vitraria with objects they received, whether on loan or as gifts, from sites closer to home than the Continent—if temporally more removed. An entry in the Royal Society's Letter Book of 1684 documents an instance when medieval glass fragments sent from the east of England became the subject of collective interrogation. On 1 April 1684, “A letter of Mr. MUSGRAVE to Mr. ASTON was read, concerning some old painted glass brought from Wooburn abbey in Bedfordshire.”Footnote 147 From the excerpt in the Letter Book, Musgrave reports: “We had an old piece of Glass, painted red & blow, shown us; it was brought from Wooburn-Abby in Bedfordshire.”Footnote 148

The reading of Musgrave's correspondence encouraged further discourse among the fellows on “the making of glass,” whereupon a disagreement transpired between Lister and Robert Hooke (1635–1703) as to the consistency of sources for the tincture of Roman versus contemporary glass.Footnote 149 Again, it was the material properties of the substance, and not any blown or poured form, that members of the society found so compelling. Lister claimed that “magnesia from magnes . . . takes away the foulness of glass: that the Romans not knowing it, their glass and urns are therefore all of a different colour from our modern glass,”Footnote 150 whereas Hooke “remarked, that the Roman glass has this colour by age, because the glass in old abbies seemed to be of the same colour.”Footnote 151

The windows of at least some medieval English churches were in fact closer to Roman glass than either Hooke or Lister knew: modern analysis confirms the reuse of late classical material, such as tesserae, to color panes at York Minster.Footnote 152 Not all the Roman glass left in Northern England had been recycled in the medieval era, though. In the late seventeenth century, excavations in and around York uncovered fragments of ancient vessels and windows.Footnote 153 The close ties between the Royal Society and the so-called York Virtuosi facilitated the exchange of these finds among the scholarly circle.Footnote 154

The correspondence of York-based glass painter Henry Gyles (ca. 1646–1709) reveals the interest contemporary artisans took in the coloration of Roman glass. Writing to Ralph Thoresby of Leeds (1658–1725) in 1699, he recalls “finding this morning . . . that small fragment of the glass urne I formerly told you of, have sent them to you, togeather with some specimens of my owne coloured glasse . . . and, Sr, I can tell you as to the ancient coloured glasse and these, I know no difference except that these exceed in greater varieties.”Footnote 155 Gyles goes on to request of Thoresby, “When you come to Yorke . . . I must beg of you bring this peice of the glass urne with you, because then I expect a glassmaker to be in Yorke that I would shew it to for the hollow roule at the bottom is pretty and odd: besides, I wou'd examine with him the nature and temper of it, which seems to be a more fix'd mettle than . . . [illegible] use.”Footnote 156 With archaeological finds such as this unearthed shard, Gyles could compare the composition of ancient glass with examples of his own enameling and perhaps even manufactureFootnote 157—assuming, that is, that the circulation of Merret's text emboldened a painter such as he to experiment with glassmaking itself.Footnote 158

Thoresby's repository, held in Leeds, included several exhibitions of materia vitraria.Footnote 159 Along with donations of antiquities from Gyles, the collection boasted additional vitreous gifts like “Adder-Beads . . . sent [from Wales] by Mr Lhwyd. . . . One is of blew Glass with white Snakes upon it. The other curiously undulated with blew, white and red.”Footnote 160 Moreover, Thoresby's commentary on others of his ancient glass possessions indicates his familiarity with contemporary excavations in London: “With the Roman Urns are often found Fragments of Glass Viols, of that Sort which is commonly called Lacrimatorys. Of the Roman Glass Ware, I have from London, Yorke, Aldbrough, and the Station near Alde; the blewish Green, and some of the White are very thick, viz. above a Quarter of an Inch. Part of a Lacrimatory from Isurium, it hath been three Inches Square. The Handle (half a foot long) of a large Vessel, found at St. Paul's; thick white Glass from the same Place. A Piece remarkably thin for those Ages, found five or six Yards deep in the Roman Wall at Aldbrough.”Footnote 161

Samples held in his Leeds repository also documented failed experiments at historical glassworks. Thoresby records one such donation from Sir Godfrey Copley (1653–1709), a member of the virtuosi and friend of the collector Thomas Kirke (1650–1706).Footnote 162 Thoresby describes the item as “a Rim of one wrought Hollow; fluted or furrowed Glass . . . with a Lump of Metal that seems to have boiled out of a Crucible, from the Ruine of the said Wall [at Aldbrough].”Footnote 163 Was it Hartlib and Merret's shared regard for the waste products of contemporary industry that primed younger antiquaries like Copley to esteem finds as ostensibly worthless as this lump?

Back in London, a flurry of post-fire building unearthed Roman shards on several occasions, as well as the odd furnace. In his memoranda book John Conyers (ca. 1633–94), an apothecary and repeat guest at the Royal Society's meetings, describes watching excavations of the Fleet Ditch (“between the fleet gate & the bridg at Holbourne”) that revealed small kilns with “a funnel to covey smoake wch might serve for glass forneses.”Footnote 164 He surmises that “though not anny potts wth glass in it whole in the fornaces was there found yet broken crucibells or Vesls for Molteing of glasses togeather wth boltered glasse such as is to be seen remaining at glass housen amongst the broken Glass, wch was glasses spoyled in the makeing was there found . . . mostly such as for cruetts or glasses wth a lipp to dropp withall & that a grenish light blew collour.”Footnote 165 A denizen of digs, Conyers also reported “ornamentall beads of Green blew like enamel” that turned up alongside “earthern ware with inscriptions & glass” at “gravel pitts . . . deep oposite & neere St pauls Schoole in London.”Footnote 166

Conyers's ability to make sense of these findings likely stemmed from his direct familiarity with the operations of a glasshouse (for example, the nearby works at Savoy) and what knowledge of glass manufacture and related crafts he gleaned from The art of glass or correspondents abroad.Footnote 167 When Roman pottery kilns were unearthed in 1677 at the building site of St. Paul's Cathedral, he likened the ancient ovens to those “at this day in use about Poland.”Footnote 168 In addition to documenting find spots, Conyers acquired antiquities from excavations for his personal collection. He made pains to classify these objects, preparing them for open exhibition. In 1691, the Athenian Mercury published a summary inventory: ““For Natural things . . . Minerals, Mettals, Stones, Gemms, Petrefactions etc. in greaty plenty. For Artificial things . . . Urns, Lachrymatories, Lamps, Gemms, Meddals.” The periodical affirms that the trove “may be in many ways useful to the Publick.”Footnote 169 In Restoration London, then, shards of Roman glass would have been examined not just alongside contemporary wares but also besides the very naturalia—minerals, metals, stones—from which any reader of Merret would recognize their tincture and translucence as having derived.

MATERIAL OVER FORM IN THE REPOSITORY

When Merret brought his materia vitraria before the fellows in November of 1662, they asked him to entrust a part of his collection to the society. Just where these donated materials would have initially been stored is unclear; mention of an official, institutional repository can only be found in records from the following year.Footnote 170 Merret's sources may have entered into the custody of Hooke, who acted as the inaugural curator of the collection until his death in 1703.Footnote 171 Hans Sloane (1660–1753) in his inventoriesFootnote 172 attributes several glass specimens to “Dr Hook,” who, in his capacity as keeper, would have overseen the accumulation of any samples further to Merret's.Footnote 173 Conyers, Lister, the French chymist Étienne Geoffroy (1672–1731), and James Petiver (ca. 1663–1713), a London apothecary and member of the society, are likewise credited for contributions of glass materials.Footnote 174 Indeed, throughout the repository's history, the fellows relied for the expansion of the collection on what Jennifer Thomas terms “proactive methods” and “spontaneous donations.”Footnote 175 The society continued to administer accessions until 1781, when the British Museum absorbed the contents of the store into its ever-deepening bowels.Footnote 176

Recent scholarship has treated the repository variously as “a physical site of reciprocal identity formation for the Royal Society and its virtuoso supporters”;Footnote 177 a three-dimensional analogue to the society's register books;Footnote 178 and a storehouse of objective “eyewitnesses” that “formed part of the Society's more general desire to authenticate written observations.”Footnote 179 The last of these interpretations is particularly germane to the role the repository played as a tangible appendix to The art of glass. Thomas argues that the fellows used the repository to address the shortcomings and suspected dubiousness of secondhand accounts.Footnote 180 She views the institution's impulse to possess objects as indicative of a larger “desire for completeness” in the accumulation of natural knowledge. Fulfilling this ambitious aspiration thus entailed looking beyond the limited testimonies of any one author to the very sources of natural histories themselves, things which the fellows could interpret collectively.

Transparency Condescends to the Opacity of Text

Writing the history of a trade in the late seventeenth century required the transposition of knowledge from the eyes and hands of practitioners to the graphic and written notes of chroniclers. The manufacture of glass is similarly characterized by the transition of materials between states. It is perhaps on account of the instability inherent in both processes that the endeavor to translate The art of glass offers a particularly conspicuous example of ekphrastic failure in the history of trades program.Footnote 181 The fellows’ demands to inspect those materia vitraria “spoken of in the booke” confirms the inadequacy of the textual medium to convey what Merret implies was in essence an intuitive art. He cites a glassworker who “always puts in all his colours, not by weight, nor measure, but by little and little at a time, and then at each time mixeth them well with the metall, and taketh out a proof, and by his eye alone judgeth whether the colour be high enough, and when too low adds more of them till he attain the desired colour.”Footnote 182

Certain of the fellows may have enjoyed a familiarity with the corpus of Merret's not insignificant bibliography, but even reading The art of glass with its acknowledged precursors to hand was not enough to “re-experience” its writing.Footnote 183 In other words, Merret's appended commentary comprised more than an armchair literature review, with objects offering their own annotations on Neri. For example, in his remarks on the recipes the Florentine recorded for coloring glass balls with “gesso,” Merret notes: “There's another pale earth with stony clots, which they use to scoure Brass, they call it Gessum. But it seems [Neri] knew not what it was.”Footnote 184 Going on to describe the material properties of this substance in some detail, Merret concludes by citing the thing itself: “To the eye it much resembles Alablaster, and is brittle as it, for so is a large piece I have by me.”Footnote 185

The accessioning of samples like this into the repository, along with gifts from Continental glasshouses and finds from excavated Roman sites, represents one measure the Royal Society took to address the essential deficiency of a written history: its inability to record the multisensory observations intrinsic to craft practice.Footnote 186 No matter the language, Merret's commentary could not equal the eloquence of the thing beheld or tasted and, as a result, fell flat in conjuring such essential material properties as color, grain size, brittleness, and salinity, all of which I have glossed above. If the fellows were to acquire embodied knowledge of glass and its raw ingredients, only the direct observation and handling of materia vitraria would do.Footnote 187

A Fresh Appraisal of the Fragment

While the contents of Merret's original collection are lost today, Birch's History and the entries of Sloane's extant inventories provide additional insight as to the direction in which the society chose to expand its cache of matter relevant to glassmaking. On 16 July 1663, the improvement of domestic crafts was back on the fellows’ agenda, as was sand, recognizable to any reader of Merret as a component of a glass batch: “Mr. Pell produced a bag containing potter's sand . . . which then gave occasion to speak of our English materials. . . . Some of the members suggesting, that this sand might be capable of more noble uses than for ovens, and that it might perhaps be found useful for vitrification.”Footnote 188

In 1669, the repository received another donation of materia vitraria. Charles Howard (1630–1713) presented to the society on red glass, after which he was “desired to produce a piece of plate of that glass.”Footnote 189 At the next meeting, “there was produced some fagots of red-streak glass sent by Mr. Read out of Herefordshire for the use of the society; which were distributed to several of the members.”Footnote 190 A decade later, acquisition and appraisal continued apace: “Mr. Henshaw produced a paper containing the milk-white pieces of glass, which had been so made by the corruption of a menstruum contained therein. This substance was very brittle, and with one's fingers might easily be crumbled into sand. This was received from Mr. John Dwight of Fusha.”Footnote 191

Items listed among the “Miscellanies” and the “Antiquities” in Sloane's catalogues indicate that the collection of materia vitraria for the repository endured long after Merret himself was unceremoniously expelled from the society in 1685.Footnote 192 With its burgeoning object appendix, The art of glass became ever present to subsequent fellows in Merret's absence.Footnote 193 The fragmentary nature of much of the material that entered into Sloane's museum testifies to the society's continued preoccupation with the components and byproducts of a glass batch—this, in contrast to Continental collectors who prized luxury goblets.Footnote 194 Merret's “Observations” as to the composition of various vitreous species and his attention to raw ingredients appear to have steered the society's collecting practices in this direction: Sloane's catalogues reveal the amassing of objects that bore witness to Merret's “wayes to make and colour Glass, Pastes, Enamels, Lakes, and other Curiosities.”Footnote 195

That the Royal Society accumulated glass shards from botched manufacturing jobs (fig. 6), intermediary processes, and archaeological digs accords with what scholars now understand as the institution's appreciation of the singular and the rare in the production of knowledge, particularly in the early eighteenth century.Footnote 196 Already in Grew's Reference Grew1681 catalogue, though, there is evidence that Merret's method of assembling a veritable archive of waste representative of glassmaking had been adapted to the study of tin mining, a trade centered around Cornwall and Devonshire.Footnote 197 Grew lists “a slag, remaining in the bottom of the Tin-Floate. Sent by Mr. Colepress” and “scum taken from melted tin.”Footnote 198 For all its ostensible failure, then, the history of trades project left its mark on the society's collecting practices, inspiring the accession of objects otherwise lost to or rendered invisible by industrial recycling economies.Footnote 199

Figure 6. Drop including a potstone impurity excavated at Broadgate, London, later seventeenth century. © Andy Chopping, Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA).

Again, the tastes of Sloane and the other fellows diverge here from those of collectors on the Continent who traditionally favored the exhibition of finished glass produced in nearby workshops.Footnote 200 To be sure, some amount of fragmentary glass, previously thought “valueless” to those outside the trade, did enter into Northern European cabinets of curiosity in the seventeenth century.Footnote 201 Just as the unearthing of Roman glass in London and York expanded interest in industrial waste products among the society's milieu, the excavation of Roman sites, such as those in Luxembourg documented by the brothers Wilhelm and Alexander Wiltheim (1594–1636 and 1604–94), encouraged a new receptivity to the shard as collectible in its own right.Footnote 202

But in the context of early seventeenth-century Antwerp, where Neri had stayed with the Portuguese merchant-banker Emanuel Ximenez (1564–1632) and observed the Venetian-style Gridolphi glassworks, what attention the merchant community paid to the process of glass manufacturing did not lead to their valuing either raw materials or evidence of failed trials as commodities worth collecting outside the trade economy.Footnote 203 Rather than licking sand or crumbling stones, connoisseurs familiar with the composition of Venetian sodic glass instead preferred to exercise their Augenmaß (visual judgment) on finished products. They took pleasure in picking out the prized crystal from within arrays of luxury objects where its vitreousness played off both naturalia and artificialia to extravagant effect.Footnote 204

The society's repository, and later Sloane's cabinets, facilitated similar comparative analysis of glass alongside other objects. No further artifice was attempted for visual effect, though, as the fellows were less keen to ogle at form than they were to handle materials—and perhaps even taste them—in order to deconstruct processes of manufacture. Items worthy of accession included the raw ingredients from which glass derived its properties, described above; by-products of failed furnace experiments; and artifacts of chemical alteration either due to time or subterranean conditions. In cabinet 199, Sloane exhibited “Cinders from the iron furnace in Sussex by Mr Fuller, glasse bottles are made of it at Brystoll” alongside the rarities of “A piece of concave mettall in glasse- belong'd to Dr Hook?” and “Chrystall glasse wch when heated turns of a red colour from France?”Footnote 205 In cabinet 216, he displayed “the cinder of slagg of some metal” together with both contemporary discards—such as “glasse found at the bottom of a lime kiln” and “two pieces of glass of bottom of a Pott from the glasse house”—and antique specimens, among them an iridescent bit of “colour'd glasse I suppose from lime” attributed to Hooke.Footnote 206

Sloane's inventories nonetheless separate contemporary glass matter from antique finds by way of the labels “Miscellanies” and “Antiquities.” That he appears to have mixed examples of these two groups in his cabinets demonstrates how the physical arrangement of his collection encouraged the diachronic assessment of colors and compositions that Gyles speaks of in his letters to Thoresby, cited above.Footnote 207 The varied composition of cabinet 216 (a and b) in particular embodies the virtuosi's fascination with glass's chemical deterioration, namely the iridescence known as Electrum britannicum.Footnote 208 Sloane brought together antique examples of this effect, originally collected by Conyers, with modern specimens displaying the same, such as that from Hooke, aforementioned; a fragment of “a glase bottle by lying in mud earth or water covered wt. the electrum or shining sulphureous vapours”; and another piece from his nephew, “a glasse bottle wch had lain in mud in Hampshire & was of the colour of the rainbow blew redish & yellow like gold the colours vivd. I saw one from Oxford take up out of the Thames. . . . Tis like the electrum antiq. on glasse vessels.”Footnote 209

Like Hartlib, members of the early Royal Society remained interested in the capacity of glass to mimic the vitreous properties of other materials. Merret in his “Observations” gives much attention to the art of forgery, as did Neri,Footnote 210 and the society's minutes reference discussions on the making of counterfeit opals.Footnote 211 Sloane's catalogues for their part record numerous examples of imitative craftsmanship, mostly the use of glass to simulate the properties of naturally occurring substances.Footnote 212 The collection at one time included “Black glasse in imitation of onyx,” “Glasse of sevll colours made in imitation of pretious stones & Intaglios,” and several counterfeit opals, as well as “Glasse or chrystalline pebbles mixd among the diamond dust or bost to cheat people.”Footnote 213 Also notable are entries of “A glasse or Past made of Chalk & clay by a Friend of Dr Hamps” and “Glasse or past in imitation of a Chrysolite of a greenish yellow colour.”Footnote 214

CONCLUSION

On 5 November 1662, Merret presented his materia vitraria to the fellows in what can only be described as a multisensory performance. Some two decades later, the cache of vitreous matter again found its way into the Royal Society's minutes.Footnote 215 The physician Fredrick Slare (d.1727) had caught an error in The art of glass that he sought to codify in the institutional annals.Footnote 216 He argued his case with evidence gleaned from direct observation of a mineral sample recently acquired for the repository. Delivering “an account of experiments . . . made with a piece of mineral called kobalt,” Slare cited Merret's published comments on the composition of zaffer only to conclude that “Dr Merret's conjecture of its being an artificial preparation is made void by this very present [the cobalt], which shews itself to be a true ore or mineral.”Footnote 217 With this new entry into the society's collection, an object once more proved its eloquence as physical commentary, augmenting Merret's own tangible addenda to Neri's book. Slare's sample had all the refutative force of a marginal note or learned gloss, yet with its visual and haptic immediacy, it succeeded in making present properties of matter too easily lost to text.

The recent unearthing of seventeenth-century glass waste at sites across London allows modern archaeologists to continue the “codification of error” that transpired at the early Royal Society (fig. 7).Footnote 218 Through scientific analysis and reconstruction, scholars might yet recover further of the materia vitraria that will for the moment remain conspicuous in their absence at the center of my account.Footnote 219

Figure 7. Gall or sandiver, the saline scum from the surface of molten glass, excavated at Broadgate, London, later seventeenth century, with the glasshouse probably closed by the early 1690s. © Andy Chopping, Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA).