By the hundreds, then thousands, the letters and telegrams rolled into the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) Washington, D.C., headquarters and its dozens of field offices across the United States. These communications—by turns desperate, angry, or resigned—sought information about the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America (FCC) and its successor organization, the National Council of Churches (NCC). Before the Second World War, the FCC was the leading ecumenical Protestant body in the United States. It represented nearly thirty-two Protestant denominations, comprising nearly twenty million Christians, committed to ecumenical unity and progressive social reform. In 1950, the NCC emerged as an even more colossal ecumenical body that included over 140,000 churches associated with African American, Orthodox, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran congregations. With an estimated membership of approximately forty million Americans pastored by 107,000 ministers, the NCC continued the FCC's commitment to social justice and became a lightning rod for popular anti-communist sentiment during the Cold War.

By May 1951, the evolution of the FCC into the NCC prompted members of a Baptist church in West Virginia to send FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover a copy of a chart titled How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches? (Figure 1). The large, foldout pamphlet featured an expansive list of FCC-affiliated clergy, and it correlated their names to alleged Communist and subversive groups. The West Virginia Baptists demanded to know if the FCC had “ever been investigated by our government” for Communist activities. “Our church desires this information so that if the Federal Council is in any way connected with communism, we will at once cease to give it our support.”Footnote 1 Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing unabated until the end of the 1960s, letters such as this one flooded into the Bureau. They recounted rumors that the FCC and, later, the NCC represented an unprecedented threat to U.S. national security interests.

Figure 1: Cover of the pamphlet How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches? (Madison, WI: American Council of Christian Laymen, n.d. [1949?]), in the Billy James Hargis Papers MC#1412, box 72, folder 17. Courtesy of the Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville.

Much of this anti-FCC literature was graphical in nature. FBI correspondents described charts, sent graphs, or developed elaborate schematic images designed to encapsulate visually the alleged relationships behind a massive Communist conspiracy at work in American religious institutions. In fact, How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches?—the intricate graphic pamphlet sent by the West Virginia Baptists—alone accounted for hundreds of letters to the FBI in the 1950s and the 1960s. As one member of the Disciples of Christ explained to Hoover, “various literature,” such as How Red “charge[d] that the Federal Council is ‘modernist’ and, far worse, communist.” A 1958 letter to the Bureau provided an elaborate homemade chart depicting the affiliations of twenty-five clergymen associated with the NCC. Eight columns representing an array of pacifist groups and “Communist ‘peace’ organizations” allowed its author to “graphically portray the interlocking and overlapping personnel of these groups.” By visually establishing a critical density of connections, the chart forced its author to conclude that the Reverend Edwin T. Dahlberg, the president of the NCC from 1957 through 1960, had affiliations with “sundry” “Communist projects and fronts.” As these graphic indexes of religious subversion proliferated at midcentury, loyal, God-fearing Americans turned to Hoover's FBI for answers. An exasperated woman from Decatur, Illinois, spoke for many when she reported that her church had “seen a photostat copy of a chart naming our church” as a member of the NCC. Distressed about all of the allegations, she pleaded with Hoover, “We hardly know what to believe. Can you please inform us of the truth[?]”Footnote 2

This essay explores how these letter writers came to view the FCC and, more broadly, ecumenical mainline Protestantism as a threat to the national security interests of the United States. To investigate this problem, one could focus on theological issues such as intellectual battles between fundamentalist and modernist Protestants. A different scholar might emphasize sociological issues embodied in the growing rural-urban divide in the United States. Still another path could map the hierarchical split between professional clergy and laypeople in many churches. In contrast to these approaches, this essay takes a different track. It focuses on three interconnected themes: first, the rise of the national security surveillance establishment in the United States; second, the development of new methods of information management in corporate and state bureaucracies; and, third, changes in popular visual culture in the immediate aftermath of World War I. This essay uses these three themes to situate the midcentury letters to Hoover and his G-men in a complex narrative that highlights how a network of federal bureaucrats, business leaders, and average citizens learned to visualize mainline, ecumenical Protestantism as a subversive threat to American national security. The emphasis on the visual here is deliberate. This essay argues that the public perception of mainline Protestantism was, in part, a function of corporate and state surveillance mechanisms that, in the literal sense of surveillance, attempted to see subversion through a number of visualization schemes and bureaucratic mechanisms that became common in the early twentieth century.

To understand how mainline Protestantism emerged as a subversive threat to national security, this essay explores a network of countersubversive institutions that emerged in American culture during the early twentieth century. Here, the essay follows the insights of political theorist Michael Paul Rogin, who argued that a “countersubversive tradition” has dominated North American culture since before the foundation of the Republic.Footnote 3 “Fearing chaos and secret penetration,” Rogin argued, “the countersubversive interprets local initiatives as signs of alien power. Discrete individuals and groups become, in the countersubversive imagination, members of a single political body directed by its head.”Footnote 4 The countersubversive tradition “defines itself against alien threats to the American way of life and sanctions violent and exclusionary practices against them.” For Rogin, the countersubversive tradition combines fear of very real political threats against the status quo with hyperbolic and fantastic symbolic representations of subversion in literature and visual art.Footnote 5

This essay adopts Rogin's concept of the “countersubversive tradition” as a heuristic for exploring how mainline, ecumenical Protestantism came to be seen as a subversive threat. It focuses on circuits created between mundane visual and technical media used to detect and record secret, clandestine, or phantasmagoric subversive threats and, in turn, publicize the constructed “fact” of their existence in the American body politic. Situated in the immediate wake of the Great War, this essay explores how the surveillance techniques of antiecumenical countersubversives initially emerged in elite governmental, military, and business circles in the very heart of America's power structures.Footnote 6 By midcentury, this countersubversive sentiment creeped out into American popular culture as amateur countersubversive hobbyists extended the surveillance of mainline subversion beyond the halls of power and into living rooms, pulpits, church basements, and high school gymnasia across the country.

To outline this relationship between the countersubversion tradition and mainline Protestantism, this essay explores three interrelated cultural trends and situates them in an emerging historiographic framework in American religious history that has seen scholars take a simultaneous interest in corporations and the national security establishment.Footnote 7 First, it considers the increasing public acceptance of political surveillance by both state and corporate actors.Footnote 8 Situated against the backdrop of the decline of the Progressive era and the outbreak of the Great War, the essay considers the rise of America's aggressive vigilant and voluntary associations that pressed federal bureaucrats, law enforcement agents, and average citizens into the service of an expanding network of surveillance mechanisms designed to scrutinize the political loyalties of American citizens and newly arrived immigrants.Footnote 9

Next, the essay explores how these new mechanisms of political surveillance had their roots in scientific business management practices and associated techniques of collecting, collating, classifying, and preserving vast archives of information.Footnote 10 In this sense, this essay follows the so-called business turn in American religious history while also expanding this “turn” beyond a focus on specific business leaders and corporations to explore the practices, techniques, and infrastructure used in corporate bureaucracies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 11 The essay argues that epistemic assumptions drawn from the business world shaped rank-and-file Protestant perceptions of society in novel and mostly unexplored ways. Thus, this essay focuses on filing techniques, information management, and new visual forms that had their roots in innovative bureaucratic schemes that emerged in corporations and government offices in the early part of the twentieth century.Footnote 12

Finally, the essay examines how surveillance and scientific management fused in the visual tools developed by business managers to facilitate increased efficiency through rigorous oversight by mapping complex social relationships. Consequently, the essay moves away from the typical focus in religious history and religious studies on representational and symbolic forms of art—paintings, prints, and figurative ephemera—to abstract forms of visual representation embodied in the organizational chart. This graphic form emerged with the development of new bureaucratic and corporate structures of social organization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 13 Although it might be tempting to find the root of visualizations of dangerous social actors in earlier religious media such as the prophecy diagrams and biblical timelines popularized by Millerites and Fundamentalists in the mid-1800s through the early 1900s, this essay argues for a different genealogy.Footnote 14 Whereas Millerite charts, for example, focused on eschatological understandings of the present in terms of an imagined future in conversation with history recorded in Scripture, the charts and graphs described in this essay relied on the epistemologies of state and corporate bureaucracies to make sense of the political and social realities of the present.Footnote 15 The circuits of information exchange embodied in the charts, indexes, and file systems discussed in this essay created links between political and religious actors and provided ways for critics of ecumenical Protestantism to project these constructed past relationships into the future with a certain amount of predictive confidence—even if they proved entirely fictitious.Footnote 16

To explore these circuits of surveillance, archiving, and exposing, the following three sections of this essay are heuristically organized around the concepts of charts, indexes, and files. In the interest of narrative coherence, each of the sections emphasizes an exemplary user of the titular technology and the associated techniques they refined. The division, however, is artificial in the sense that the techniques discussed in each section are irreducibly intertwined with the themes of surveillance, information management, and visualization outlined in this introduction.

Charts: Visualizing Interlocking Directorates

Before diving into the complex visualization schemes used to comprehend the alleged Communist infiltration of the FCC and NCC, we first must take a detour through the offices of the U.S. War Department's Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) in Washington, D.C. In 1923, Lucia Ramsey Maxwell, a librarian at CWS, created an elaborate chart purporting to document the influence of the “Social-Pacifist Movement” on the Women's Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC) and the National Council for the Prevention of War. Divided into three vertical rows, the chart connected fourteen national organizations—including the National League of Women Voters, the Girls’ Friendly Society, the Needlework Guild of America, the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and the Young Women's Christian Association—with a dizzying network of intersecting horizontal, diagonal, and vertical lines (Figure 2). From this web of interconnected organizations emerged a massive conspiracy of suffragists, pacifists, liberal Protestants, and women's rights activists all working in concert to undermine the military readiness of the United States.

Figure 2: Lucia Ramsey Maxwell's spider-web chart as it appeared in the March 22, 1924, issue of the Dearborn Independent.

Recognizing the incendiary implications of her chart, Maxwell maintained tight control over the original handmade copy. “[A]t times,” one of her friends recalled, she showed the chart “to various persons in the patriotic societies at Washington. Finally, someone asked to borrow the original chart, and rather than lend it, Mrs. Maxwell permitted a photostat to be made, of which there were several copies.” From this handful of photostatic copies, Maxwell's chart spread throughout the War Department and Justice Department. After copying the chart, Maxwell sent the original copy to President Warren G. Harding, “who kept it in his desk until his death” in 1923. Upon reviewing one of its photostatic copies, a young Justice Department bureaucrat named J. Edgar Hoover enthused, “One can gain more in my estimation from examination of such a chart than he can from reading voluminous reports dealing with the same subject.”Footnote 17 Soon copies found their ways into the hands of likeminded leaders of countersubversive groups outside the federal bureaucracy.

Maxwell's chart might have faded into bureaucratic obscurity had industrialist and automobile manufacturer Henry Ford not intervened. In March 1924, Ford's Dearborn Independent published a full-page edition of Maxwell's chart. Paired with an anonymous article, the Dearborn Independent catapulted Maxwell's chart to the forefront of domestic politics.Footnote 18 Irate women's groups demanded that the Independent retract the publication, while the WJCC hired private detectives to track down the anonymous authors of the chart and the accompanying article. Reprinted versions of Maxwell's chart appeared in newspapers and pamphlets across the country. The War Department, embarrassed by the public relations debacle caused by the chart, acknowledged Maxwell's role in creating it and ordered copies burned. So-called patriotic societies of the day rushed to preserve copies.Footnote 19 The lucky few who possessed one of the early photostats framed them.

Several historians have highlighted the significance of Maxwell's spider-web chart. Most narratives contextualize the chart's production in efforts of the CWS, Military Intelligence Division (MID), and the War Department to protect the rapid expansion of the military during the Great War.Footnote 20 Military advocates, fueled by the Woodrow Wilson administration's efforts to put the United States on a war footing, warned against subversive elements in the general population. The Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 compounded these concerns as pacifist-leaning women's groups, labor unions, and progressive religious organizations increasingly drew the ire of countersubversive groups. Historians have pointed to Maxwell's chart as a salient manifestation of the collapse of civil trust in the decade following the war.Footnote 21 Yet, the spider-web chart—often derided by contemporaries and historians alike as crude, simplistic, and amateurish—did more than embody the jingoism and paranoia of the postwar moment. It bequeathed a visual touchstone to subsequent generations of countersubversive activists seeking to impose order, uniformity, and coherence on seemingly unconnected social actors and cultural events. Maxwell's chart achieved this pioneering feat by appropriating and repurposing graphic strategies used by corporations, scientific institutions, and government agencies to map complex institutional relationships.

The spider-web chart is perhaps best classified as an “organization chart.” It synthesizes the three critical visual elements of this graphic genre: analysis, relationship, and hierarchy.Footnote 22 In the late 1800s, the art of charting organizational structures emerged in large-scale, corporate entities—especially in railroads and financial institutions—that needed novel means to administer complex relationships among employees and manage information across vast distances. With Daniel McCallum's 1855 “Diagram Representing a Plan of Organization of the New York and Erie Railroad” (Figure 3), organizational charts became an increasingly important way for corporate managers to grasp the size, scope, and interrelationships of their companies.Footnote 23 Visual oversight in the form of charts, graphs, and timetables became an essential component of the “Systemic Management” or the “Scientific Management” movement developed by the likes of Frederick W. Taylor and implemented by armies of nameless managers seeking to impose order on vast corporate structures.Footnote 24

Figure 3: D. C. McCallum's New York and Erie Railroad Diagram Representing a Plan of Organization: Exhibiting the Division of Academic Duties and Showing the Number and Class of Employés Engaged in Each Department: From the Returns of September (New York: New York and Erie Railroad Company, 1855). Courtesy of the Library of Congress and available online at https://www.loc.gov/item/2017586274/, accessed August 25, 2020.

By the early 1900s, a large body of literature theorized that the effort to routinize and schematize management through visualization allowed corporate board members to delegate administration to their subordinates and create more efficient means for overseeing their managers and superintendents. The effect of such corporate surveillance was simultaneously to analyze an institution while integrating it into a coherent organizational structure. As Willard C. Brinton noted in Graphic Methods for Presenting Facts, “organization charts are an excellent example of the division of the total into its constituent components.” Likewise, in Graphic Charts in Business, Allan C. Haskell argued, “Probably one of the most important uses of graphic charts . . . is for the development of analytical thinking and investigation.” But, alongside analysis, organization charts could also impose unity on isolated components. According to Winfield A. Savage's 1926 study of the use of charts and graphs by business executives, “An Organization Chart is the surest, quickest and most comprehensive means of showing what the organization is, the various divisions to which each is responsible and all subordinate thereto.” For the businessman, charts reduced complex relationships, figures, and structures into simple patterns that made it possible to “manage his business efficiently and profitably.” In fact, a graph not only made things legible at a glance, it also framed what a viewer could and could not see; a graph, in the words of Henry D. Hubbard, a member of the National Bureau of Standards, “compels the seeing of relations.” As business historian JoAnna Yates makes clear, early advocates of graphical representation exaggerated the objective nature of graphs to render complex information meaningful at a glance. This supposed objectivity, however, was also in tension with the power of graphs to “perform a persuasive function” on their readers.Footnote 25

Within the visual context of the first quarter of the twentieth century, the popularity of scientific management and the cultural cachet of charts and graphs all but assured the influence of Maxwell's innovative spider-web chart for two reasons. First, her chart decoupled the organizational chart from corporate management. The spider-web chart did not map relationships inside a corporation for the purposes of increased efficiency but, instead, purported to document secret relationships between actors who intended to dissimulate their connections. Second, her chart appropriated techniques originally developed by populist and progressive critics of corporate trusts and monopolies to document associations among actors. Activists, cartoonists, and satirists appropriated corporate charts and graphs into older visual traditions to generate fresh ways of criticizing corporate interests. Elaborate corporate organizational charts mutated into baroque organic forms: spider webs, octopuses, and anthropomorphized creatures transformed seemingly benign graphs and charts into monstrous, dangerous social agents.Footnote 26 As historian Peter Knight has noted, “It was important to Populist, Progressive, and Socialists critics alike to find a way of rendering visible the networks of power against which they were protesting.” Quoting Louis Brandeis's study of the “money trust” problem, Knight points out that many critics of monopolistic trusts needed new ways to comprehend the abstract relationships between business leaders, corporate boards, and the corporations they managed. As a result, they appropriated new visual tools from professional management “to visualize the ramifications through which the forces [of corporate trusts] operate.”Footnote 27

Maxwell's chart had a clear relationship to charts that appeared in the 1910s that represented the “corporate interlocks,” “interlocking memberships,” or “interlocking directorates” of corporate directors. These organizational charts attempted to depict graphically how a tiny number of business leaders sat on the boards of directors of many of the country's railroads, banks, and manufacturing companies. The most significant chart in this genre was Philip J. Scudder's 1913 “Diagram Showing the Affiliations of J. P. Morgan & Co., . . . with Large Corporations of the United States” (Figure 4). Also known as Exhibit No. 243 of the Pujo Committee's Money Trust Report, Scudder's elaborate, hand-drawn diagram showed that J. P. Morgan “interlocked” with dozens of corporate boards and, therefore, singlehandedly controlled a significant portion of the U.S. economy.Footnote 28 Variously described as a “spider web” and an “octopus,” the chart, as Brinton noted a year later, “shows the application of the graphic method to such complex situations as it is almost impossible to portray with language alone.”Footnote 29 Scudder's chart inspired myriad imitators; however, most never rose to the Pujo exhibit's complexity or refinement of detail. Instead, many of Scudder's imitators produced simpler “corporate interlock” charts, such as those favored by the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union activists.Footnote 30 The IWW depictions of corporate interlocks in the coal industry flattened Scudder's intricate chart into much simpler linear connections among corporate boards and a handful of business titans.

Figure 4: Philip J. Scudder's “Exhibit 244: Diagram Showing Principal Affiliations of J.P. Morgan & Co. of New York, Kidder, Peabody & Co. and Lee, Higginson & Co. of Boston, First National Bank, Illinois Trust & Savings Bank, and Continental & Commercial National Bank of Chicago” in Money Trust Investigation: Investigation of Financial and Monetary Conditions in the United States Under House Resolutions Nos. 429 and 504 Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Banking and Currency, House of Representatives, February 25, 1913. Courtesy of FRASER and available online at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/80/item/23677, accessed August 25, 2020.

The irony is that Maxwell's chart that depicted the alleged interlocking directorates of subversive women's organizations drew on the visual and rhetorical metaphors developed by populist, progressive, and outright revolutionary critics of big business.Footnote 31 Much like Exhibit No. 243 for the Pujo Committee or the IWW's charts of mining industry interlocks, Maxwell's chart became a powerful tool for seeing relationships among abstract and seemingly unrelated social forces. Unlike progressive or radical representations of corporate interlocks, however, Maxwell's chart struck at the heart of America's progressive voluntary societies. It charged that many respected organizations could not be trusted by their rank-and-file members because the societies’ various boards interlocked with a network of suspicious, unsavory, or foreign agents. If progressives and populists used their interlocking directorate charts to depict a cabal of industrial oligarchs organized against workers, then an emerging network of antiradical countersubversives would use Maxwell's chart to visualize the amorphous network of national security threats that they saw emerging in the United States in the turbulent wake of World War I.Footnote 32

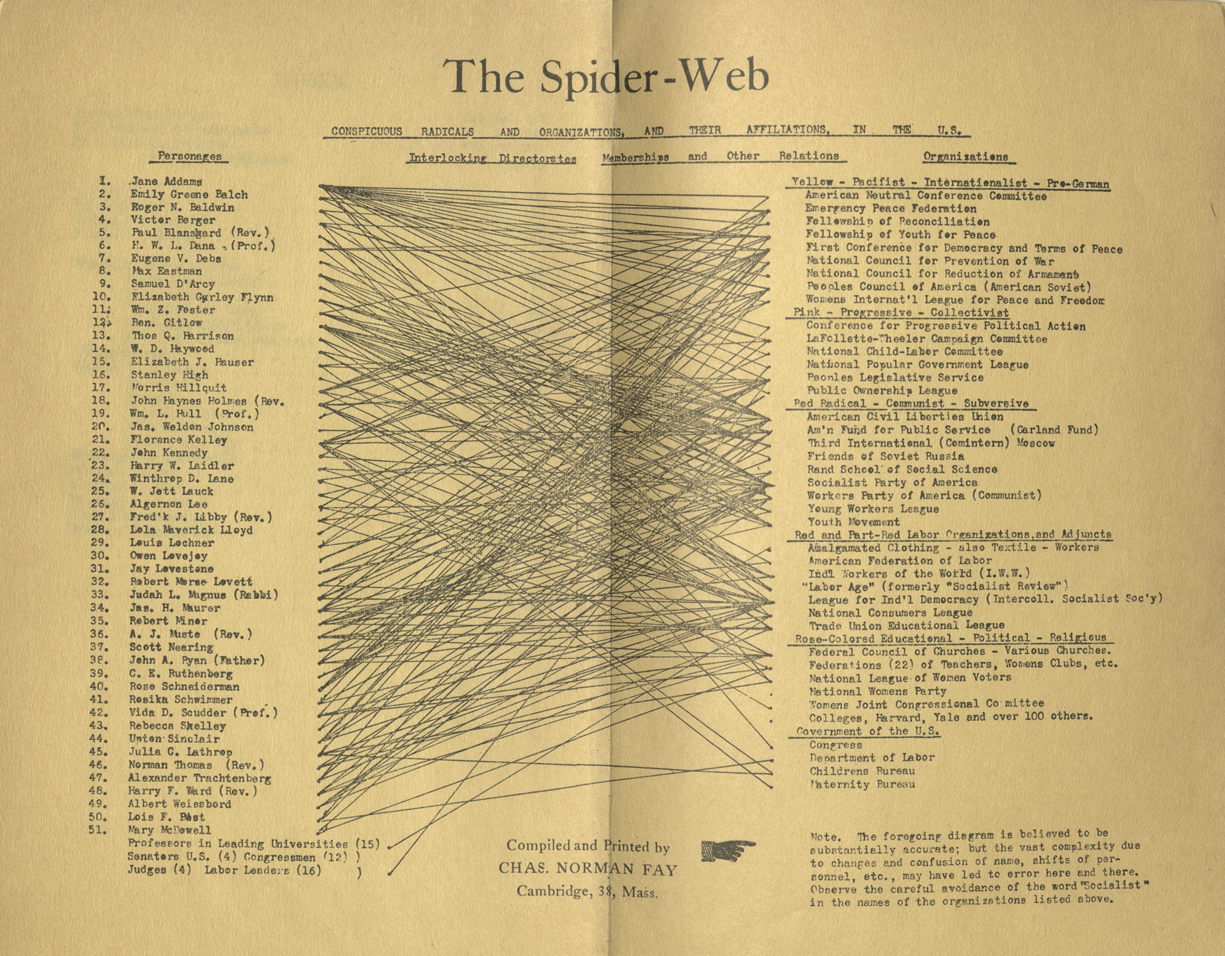

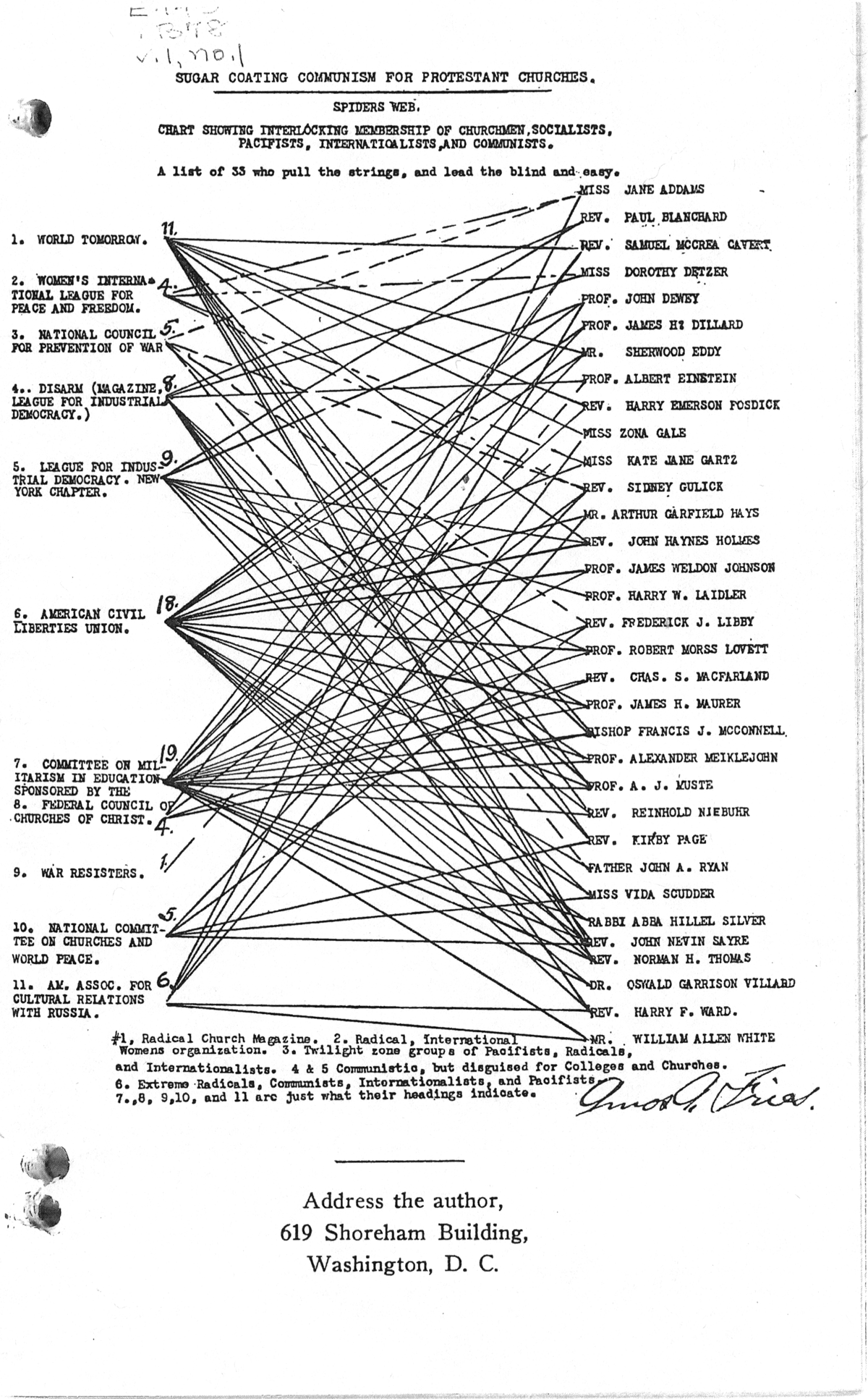

Although Maxwell's chart did not launch a direct attack on the FCC, it did lay the foundation for such attacks, and they came in quick succession. In 1926, Charles Norman Fay, a prominent Chicago industrialist, appended a graph titled “The Spider-Web” (Figure 5) to his book Social Justice, a study that linked socialism, trade-unionism, and progressive religion to revolutionary Marxism and Communism. His chart was likely the first to introduce the FCC into a web of “Rose-colored” religious organizations that interlocked with a massive network of “conspicuous radicals.”Footnote 33 A year later, retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Le Roy F. Smith, dedicated the entirety of Pastors, Politicians, Pacifists (co-authored with E. B. Johns) to attacking the FCC. Smith and Johns went a step beyond both Maxwell and Fay in that they explicitly intended the book to serve as a useful reference guide for their readers. They included “a very thorough and complete TOPICAL, ORGANIZATION, and PERSONNEL INDEX” and an elaborate “Family Tree” interlock chart (Figure 6) that “graphically portray[ed] the Organization, the Cooperating Bodies, and the Spheres of Influence of the Federal Council.”Footnote 34 By the early 1930s, Maxwell's former CWS boss, Amos A. Fries, published “Sugar Coating Communism for Protestant Churches,” his very own interlocking subversive chart targeting churches (Figure 7).Footnote 35 His chart and its companion pamphlet revealed the FCC's “interlocking membership” with other organizations—including the American Civil Liberties Union—that hoped to raise “a Red Flag where now waves the Stars and Stripes.”Footnote 36 Then, in a final significant visual mutation, Henry Bourne Joy, president of Packard Motor Car Company, published the widely circulated “Our Protestant Churches in Politics” (Figure 8).Footnote 37 His chart surpassed its predecessors in neatly depicting the “interlocking” relations between the FCC and subversion. Sleek and rectilinear, “Our Protestant Churches” dispensed with jumbled lists and messy connecting lines in favor of a simple, text-based index that made for easy reference by readers.

Figure 5: “The Spider-Web,” from Charles Norman Fay, Social Justice: The Moral of the Henry Ford Fortune (Cambridge, MA: Cosmo, 1926). Special thanks to Adam T. Beauchamp, Humanities Librarian at Florida State University Libraries, FSU's Interlibrary Loan staff, and Eli Boyne, Rare Books Library Associate at Tulane University's Special Collections Division of Howard-Tilton Memorial Library for securing this image.

Figure 6: “Chart of Organizational ‘Hook-up’” or “The Family Tree” from Le Roy F. Smith and E. B. Johns, Pastors, Politicians, Pacifists (Chicago: Constructive Educational Publishers, 1927).

Figure 7: “Sugar Coating Communism for Protestant Churches: Spiders Web: Chart Showing Interlocking Membership of Churchmen Socialists, Pacifists, Internationalists, and Communists,” from Amos A. Fries, Sugar Coating Communism for Protestant Churches (Washington, DC, 1932), in the Pre-Pearl Harbor Pamphlets Collected by John Bowe, Minnesota Historical Society Library. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society Library.

Figure 8: “Our Protestant Churches in Politics: Diagram of Religious Political Propaganda Machine,” an advertisement published by Henry B. Joy in The Detroit Free Press, November 2, 1930.

Thus, less than a decade after the publication of Maxwell's chart, a wave of countersubversive charts had used its form and spirit to plug the FCC into a broad network of allegedly “radical” groups. The publication of these charts also indicated important changes in public discourse related to charges of clandestine subversion. First, if the War Department had once tried to destroy Maxwell's chart and bury its accusations, then, by the end of the 1920s, retired Army officers and millionaire industrialists could, as private citizens, publish incendiary charges that implicated a wide range of voluntary associations in a web of subversive activities. Going on the record was no longer a public relations disaster; rather, it sold books and pamphlets, and it generated media interest. Next, by turning their attention to ecumenical and modernist Protestant groups, Fay, Smith, Fries, and Joy pointed to the declining influence of women's groups in the 1920s and anticipated the resurgence of interest in Social Gospel–inspired ideas during the Depression era of the 1930s. As the influence of self-proclaimed conservative and patriotic women's groups grew—especially the American Legion and Daughters of the American Revolution—and progressive groups split over their responses to the failures of alcohol prohibition and controversies over progressive social policies, much of the suspicion once aimed at women's voluntary organizations shifted to religious organizations and civil liberties groups. Even as worries over the loyalties of the board members of the WJCC or Women's Christian Temperance Union declined, by the end of the 1920s, spider-web charts had emerged as an important visual tool used by a network of countersubversive activists to depict the relationships among a range of American institutions.

Finally, and most significantly for this essay, the authors of the post-Maxwell charts intended them to be used as reference devices. These new charts simplified Maxwell's difficult-to-read chart. Their authors used the graphic form to create practical interlock charts that readers could use in the service of further research. By incorporating more robust indexical tools into their charts, these graphic devices could work in tandem with book- or pamphlet-length narratives, documentary anthologies, and journalistic accounts that readers could use to “confirm” allegations of subversion. As the second and third sections of this essay argue, this development had long-term implications as it encouraged a consuming audience to investigate the connections alleged in the graphs. These charts also helped readers assemble their own evidence in the service of visualizing subversion. Because of the pioneering work of Fay, Smith, Fries, and Joy, these complex tapestries of dangerous connections would come to include an immense network of mainline Protestant denominations and parachurch organizations.

Indexes: Correlating Subversion

The campaign to chart “the spider's web” inaugurated by Maxwell and perpetuated by Fay, Smith, Fries, and Joy had its roots in a concerted effort to stamp out religiously inspired political dissent. Federal bureaucrats and business leaders honed in on the powerful, well-funded FCC as a threat. Formed in 1908 as an ecumenical body to represent the social reform efforts of thirty-two Protestant denominations, the FCC grew rapidly in size and influence, garnering high-profile support from the likes of Woodrow Wilson, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr.Footnote 38 The FCC's willingness to address controversial social and political matters related to labor, military service, and social justice made it especially vulnerable to critical attacks. To their critics, mainline clergy became part of a diffuse conspiracy to empower organized labor and neuter the military in the decade following the Great War.

Before the outbreak of World War I, the FCC acknowledged industrialization and the growth of organized labor as two of the most significant social problems facing the country. Even though the council remained ambivalent about striking, it created a network of commissions to investigate the labor problem. The FCC angered business leaders during the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s after it appeared to side with organized labor over business interests. Most notoriously, its scathing report condemning management's actions in the 1910 Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Steel Works strike made the FCC an easy target for probusiness advocates for more than a decade.Footnote 39

With the outbreak of World War I, the FCC's diverse body of churches proved mostly supportive of the war, but the organization, nonetheless, angered many critics by protecting pacifists, supporting minority rights in the volatile domestic political environment during and following the war, and opposing military preparedness training in public schools.Footnote 40 When combined with the council's commitment to addressing the labor problem and its willingness to address controversial theological concerns such as evolutionary theory and scriptural criticism, the FCC's wartime positions created tensions between the professional clergy that administered the council and the laity that comprised its constituent bodies.Footnote 41 The progressive clergy often advocated issues and encouraged social reforms that were out of step with many of the rank-and-file in the pews.

The FCC's willingness to wade into these controversial social and political issues earned it the suspicions of powerful business leaders and prominent figures in the federal bureaucracy. Notably, in the 1910s and 1920s, the FCC attracted the investigative scrutiny of the Bureau of Investigation (BI), the precursor of the modern FBI. During World War I, the BI and its allies in Military Intelligence monitored pacifist FCC clergy who spoke out against the U.S. participation in the war. The FCC's support of labor unions and its progressive position in favor of more equitable treatment for African Americans brought further attention to the council after the war, especially by MID.Footnote 42 The BI also paid close attention to the FCC in the aftermath of the extralegal Palmer Raids (executed in the winter of 1919–1920), in which the Department of Justice rounded up and deported suspected Communists and foreign nationals. BI agents investigated FCC clergy who drafted a resolution calling for “legislation by Congress to protect aliens in the United States” and another statement alleging “illegal acts by Department of Justice Agents in connection with the apprehension and detention of alien Communists” during the Palmer Raids.Footnote 43

Yet, despite these tensions, the FCC counted as its members prominent Protestant denominations, including the Presbyterian Church, USA, and major branches of the Methodist, Lutheran, and Baptist churches. By the end of the 1940s, the FCC represented thirty million Christians in the United States. Given the FCC's controversial track record, it is unsurprising that opponents of organized labor, enemies of Communism, and congregants suspicious of centralized religious authority turned their critical gaze toward the council. During the Depression and enduring throughout World War II, a new coalition of FCC critics formed from the legacy established by the likes of Maxwell, Fay, Fries, Joy, and many, many others. Led by industrialists, former Communists, military analysts, union busters, and prominent laypeople, these FCC critics produced charts and narratives documenting the infestation of Protestant groups with subversives. These documents, like Maxwell's chart before them, had their origin in the business, law enforcement, and bureaucratic practices of the early twentieth century. Maxwell's chart relied on her private research—research she modeled on the professional techniques developed by the CWS, MID, and BI. These agencies used large, sophisticated filing systems to translate individual, disconnected acts of observation into usable, archived pieces of information and assembled them into integrated, composite accounts of the actions and beliefs of alleged subversives.Footnote 44 Although it might be tempting to see the production of such files and dossiers as simplistic, guilt-by-association rhetorical gestures, in actuality, these techniques of surveillance and information coordination were rooted in the rigorous production of “facts.”

In the 1940s, a new generation of anti-FCC red hunters took up these tools of factual fabrication. No document more clearly embodied these techniques than Verne P. Kaub's How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches? Footnote 45 As with the spider-web charts of the 1920s and 1930s, How Red exposed the alleged Communist activities of ecumenical, theologically liberal Protestants. Kaub's controversial American Council of Christian Laymen (ACCL) published the document as an incendiary call-to-arms for conservative Protestants. The production of How Red involved the cooperation and coordination of a host of important midcentury countersubversives. Kaub, a retired public relations officer for Wisconsin Power and Light Company, worked with Allen A. Zoll, a New York advertising executive, who ran the National Council for American Education (NCAE). In turn, Zoll relied on the file system developed by notorious Communist-turned-red hunter J. B. Matthews to research the pamphlet.

In 1949, Zoll—an anti-Semite, Nazi sympathizer, and former leader of the fascist Christian Front—founded the American Intelligence Agency (AIA). Zoll's organization began as an anti-communist group but evolved into the far more complex NCAE. Over a decade of operation, the AIA and NCAE served as quasiprivate investigative agencies that gathered a massive archive of information to monitor what Zoll perceived to be a conspiracy among foreign Communist agents, clergy, and progressive educators in the United States.Footnote 46 In the education field, Zoll and Kaub published a short, narrative pamphlet titled How Red Are the Schools? It warned readers, “For a generation, your tax money helped pay the salaries of poisonous propagandists who have been endeavoring to make radicals out the youth of our land.”Footnote 47

Shortly after collaborating on How Red Are the Schools?, Zoll and Kaub hatched a scheme to publish a new pamphlet attacking the FCC. Using a similar title but opting for a nonnarrative, graphic format, How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches? would play a pivotal role in shaping how Americans would view mainline, ecumenical Protestantism in the second half of the twentieth century. To distribute the leaflet, Kaub created the ACCL to distance their anti-FCC organization from Zoll's already well-known NCEA. Kaub understood the implications of his connections to both councils, and he wanted to distinguish the two boards and avoid “creating more of an ‘interlocking directorate’” by setting up the ACCL without Zoll serving in a formal capacity.Footnote 48 Kaub incorporated the ACCL in 1949 in Wisconsin with A. W. Larson, a Congregationalist, and E. E. Espelien, a Lutheran, both of whom were retired businessmen in Madison.Footnote 49

The research behind How Red reflected the complex, collaborative nature of mid-twentieth-century countersubversion. A small network of organizations and citizens managed file systems—massive collections of clippings, letterheads, business cards, public documents, private memoranda, and a host of other ephemera—that allowed them to document alleged Communist subversion in the United States. How Red emerged from contributions from Kaub but relied mostly on Zoll's use of J. B. Matthews's extensive personal index of names and organizations. Matthews had served as lead researcher of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which Texas Democratic Representative Martin Dies chaired from 1938 to 1944. Matthews based his research on a private archive and index he created in the 1930s as he evolved from a Communist sympathizer into an anti-communist investigator. By the 1940s, Matthews split his time between researching un-American activities for the Dies Committee and making sure that William Randolph Hearst's newspapers remained Communist-free.Footnote 50

To understand the production of How Red, it is important to consider how file systems such as those used by Matthews and Zoll worked. The following discussion focuses on Matthews's methods because he frequently discussed them in public. Unlike Matthews, the secretive Zoll, who employed nearly identical methods, refused to offer interviews to the press to discuss his research techniques. On the rare occasions when he interacted with reporters, Zoll proved contentious and unrevealing. In one of his only on-the-record interviews, an agitated Zoll interrupted a McCall's magazine reporter by sputtering, “If you smear me, I'll cut your throat.”Footnote 51 In contrast, the media-savvy Matthews courted the press and bragged about his voluminous files and the exhaustive nature of his research. A compulsive collector and cataloguer, Matthews reported how he used an elaborate index card system to catalog and cross-reference every name and organization in his collection. “I have about a quarter-million cards listing affiliations with Communist and Communist-front organizations,” Matthews told the New York Times in 1953.Footnote 52 Following his association with the Dies Committee, many observers believed Matthews's personal dossier collection to be second only to the FBI's in scope and content.Footnote 53 For individuals connected to Communism by Matthews's indexing methods, the results could be personally and professionally devastating.Footnote 54

Matthews began collecting letterheads, business cards, lunch programs, and other bits of ephemera that he weaponized in the 1930s to create connections between individuals and purported Communist-front organizations. Letterheads played a prominent role in his research techniques. In his memoir, Odyssey of a Fellow Traveler, letterheads emerged as the Communist Party's primary mechanism for manipulating non-Communists:

Around every injustice which might conceivably stir a spark of protest in the bosom of some middle-class citizen, the communists have built an organization—replete with executive secretary, chairman, sponsors, slogans, and letterhead. The revolutionary tactic runs somewhat as follows: If we cannot catch them with the bait of the Scottsboro Boys or the Release of Mooney or the Plight of the Arkansas Sharecroppers, we may, perchance, draw them into the Struggle for the Territorial Integrity of China.Footnote 55

Once enlisted to contribute to these front organizations, good, middle-class Americans found themselves listed on mailers, flyers, and letterheads circulated to other unsuspecting donors. Gullible Americans became pawns in an immense Communist conspiracy. They also found themselves indexed on one of Matthews's cards.

The archival systems developed by the likes of Matthews and Zoll exploited the flexibility of index cards to correlate multiple levels of information by connecting names, dates, places, and institutions. Like the graphic techniques appropriated by Maxwell a generation earlier, the indexing systems of countersubversives relied on the innovative modernizing business efficiency trends popularized in corporations in the early twentieth century. Index cards allowed for the visualization of relationships and for the easy reshuffling of these relationships—subject cards could reference publications, while cards listing publications could cross-reference subjects, for example. The result is that the easy mutability, portability, and connectability facilitated by card indexing provided the agents of blacklisting with a means for producing connections among people, events, and publications.Footnote 56

Through their collaboration on the ACCL's How Red, Matthews and Zoll transformed the pamphlet's reader into an amateur investigator. In a literal sense, How Red is nothing more or less than an index of relationships between individuals and organizations. Kaub's final document concretized the process of cross-referencing and indexing techniques honed by Matthews and Zoll into a single document. Gone were the confusing visual relationships created by Maxwell's spider-web chart that connected individuals and organizations with a tangled mess of lines. In their place were—like Joy's sophisticated index chart—neat lists of individuals and organizations. Following every suspect pastor, the reader found a series of numbers that cross-referenced a separate list of organizations. In turn, capsule descriptions accompanying each organization narrated its deceptive, Communist-related activities (Figure 9). The index then connected these descriptions to authoritative sources—New York's Lusk Committee Report, California's Committee on Un-American Activities, and Matthews's pervious publications under the auspices of the Dies Committee. In short, How Red is an index of indexes designed to allow its reader to generate patterns between religious leaders and Communist front groups.

Figure 9: Annotated cover and interior page from How Red Is the Federal Council of Churches? in Federal Bureau of Investigation HQ file number 62-100432, serial number 1, Subject: American Council Of Christian Laymen. Courtesy of the Internet Archive's Ernie Lazar FOIA Collection available online at https://archive.org/details/AmericanCouncilOfChristianLaymenVerneKaubHQ62100432, accessed August 25, 2020.

The influence of How Red on midcentury Protestantism was immediate. Newspapers across the country covered the pamphlet throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Major dailies, including the New York Times, noted its incendiary charges but allowed FCC defenders the last word.Footnote 57 Local papers were much more critical of the FCC. Some editorials reprinted the pamphlet's charges and used them to implicate local church officials in its spider's web of conspiracy. Churches advertised using the pamphlet in Sunday sermons and Bible study groups.Footnote 58 One story recounted how the chart prompted a newspaper editor in California to offer Dr. E. Stanley Jones, a Methodist missionary indexed in the chart, $1000 to submit to a two-hour interrogation with a stenographer present.Footnote 59 By the FBI's own estimation, the chart had driven a considerable amount of the negative mail urging the Bureau to investigate the FCC and its descendent bodies, the National and World Councils of Churches. Further, as religious historian Peter J. Thuesen has noted, the chart helped drive a significant amount of the distrust in the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.Footnote 60

The chart's notoriety and popularity in the 1950s followed close behind calls by public figures for laypeople to be on guard against the threat of collectivism in their churches. Most infamously, in March 1947, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover told the HUAC, “I confess to a real apprehension so long as Communists are able to secure ministers of the Gospel to promote their evil work and espouse a cause that is alien to the religion of Christ and Judaism.”Footnote 61 Hoover's fleeting reference to Communist efforts to manipulate “ministers of the Gospel” proved a godsend to the Zolls, Matthewses, and Kaubs of the world. Kaub appended Hoover's words to an updated 1949 edition of How Red, and the quotation regularly appeared in literature printed by countersubversive organizations. Hoover, intentionally or otherwise, had waded into almost a half-century of controversy over the nature of American Protestant activism and, in the process, seemed to endorse the role of blacklist entrepreneurs and amateur countersubversive investigators.

Files: Seeing Like the FBI

Hoover's dire warnings about the Communist threat to American religious institutions helped cultivate the deep distrust many laypeople in mainline denominations already harbored against their ministers and church leaders. His words seemed to validate the rumors and whispers promoted by over thirty years’ worth of countersubversion activists. Maxwell's spider-web chart and its many descendants (including Kaub's index of indexes) had taught vigilant anti-communists how to visualize the relationships among Communists, fellow travelers, and church leaders. By the middle of the century, figures ranging from national titans such as J. Edgar Hoover to obscure redbaiters like Verne P. Kaub insisted that researchers could best recognize Communists not by documenting their direct actions but, instead, by tracking down their hidden associations. Behind every effort to chart these associations and every graphic representation of communistic connections stood an archive of ordered, correlated information. By midcentury, any aspiring Communist hunter understood that filing cabinets and index cards had become the requisite investigative hardware of the era. This climate of paranoid vigilance, facilitated by legislative investigative committees and surveillance entrepreneurs, found ample reinforcement in the rise of American mass media culture, especially in popular media, and in the widespread availability of cheap mechanical textual production and efficient information storage.

At midcentury, innumerable books, motion pictures, and radio and television programs idealized the limitless research files of surveillance agencies such as the FBI. In the popular imagination, the Bureau's files represented the federal government's ability to watch its citizens and to retrieve even the most obscure bit of information and mobilize it as evidence in a criminal investigation. Popular television programs, such as I Led 3 Lives (broadcast from 1953 to 1956), claimed to draw their “fantastically true” stories from exclusive access to the secret files of FBI informant Herbert A. Philbirck and other famous counterspies.Footnote 62 As media historian Michael Kackman has argued, producers filmed I Led 3 Lives and similar programs in a “semidocumentary” style that blended “‘based-in-fact’ truth claims” with “a kind of civic nationalism” to allow viewers to imagine themselves playing an important role in the contemporary battle against Communism.Footnote 63

This sensibility reached its popular visual and narrative apotheosis in Warner Brothers Studio's Jimmy Stewart film The FBI Story.Footnote 64 Described by media scholar Thomas Doherty as a “biopic of bureaucracy,” this 1959 film focused not on Stewart's portrayal of G-man Chip Hardesty but on the way the character becomes a “cog in the precision machineworks of [J. Edgar] Hoover-style law enforcement.”Footnote 65 The film made clear that the real heroes of the FBI are not only its faceless contingent of agents, researchers, secretaries, and lab assistants but also its boundless infrastructure of surveillance, intelligence gathering, and information management. As the prelude of the film insisted, no criminal could escape the “broad research powers of the FBI—its high-speed communications, its endless flow of vital correspondence, a laboratory equipped to analyze all documents, a serology section geared to break down every known blood sample, a firearms section containing two thousand weapons.” Long, patient tracking shots lingered over an ocean of file cabinets and a roiling mass of agents combing through their contents in search of evidence. The message was clear: surveillance and information management went hand-in-hand; seeing and recording what one sees were essential, interrelated tasks in the war against subversion and crime in the United States.

Yet, regardless of the deep faith many Americans had in the surveillance conducted by law enforcement agencies, federal and local laws restricted access to the information generated by such activities. The secrecy surrounding official investigations into the threat of Communist subversion drove intense public interest in the matter. The midcentury period witnessed an explosion of countersubversive groups seeking to bridge the information gap between the FBI's secret files and the public clamor for information regarding Communist infiltration of American institutions. As Major Edgar C. Bundy—a retired Air Force intelligence officer, Baptist minister, chairman of the Church League of America, and a leading critic of the FCC-style liberal ecumenism—informed his readers, “A citizen . . . cannot go to a local FBI office or to Mr. Hoover's headquarters, and ask for the names of all clergymen or church groups which have aided the cause of Communism, and expect to get them. They are not available. However, this does not mean that they do not exist.”Footnote 66 In his books, newsletters, and public speeches, Bundy advised concerned laypeople to subscribe to his newsletters and to read the publications of organizations ranging from Kaub's ACCL to Robert Welch's John Birch Society.Footnote 67 Bundy used Hoover's public calls for vigilance as endorsements for his activities and those of his countersubversive peers.

A network of private organizations emerged that operated in a bureaucratic gray area between nonprofit religious educational organizations and private investigative firms. Many maintained their own subversive lists, which subscribers could purchase. Some of these organizations had a national scope with leaders who, such as Bundy, had direct connections to military intelligence and law enforcement, or they were former employees of the American Legion or similar countersubversive organizations. Four of the largest religiously affiliated countersubversive operations—M. G. Lowman's Circuit Riders Inc., Billy James Hargis's Christian Crusade, Bundy's Church League of America, and Kaub's ACCL—were nonprofit educational organizations supported by business, law enforcement, and religious interests. These groups fused the intelligence-gathering, secrecy-obsessed culture of the midcentury period with the populist antielitism of twentieth-century anti-communism into a potent attack on midcentury mainline, ecumenical Protestantism. Students of their publications learned how to see the Communist plot against America's churches and, in turn, became vigilant private investigators who could connect the dots of conspiracy when the FBI could not publicly do so.

Against this cultural backdrop, it should not be surprising that private surveillance became a hobby for Americans from a variety of political or social backgrounds. Civic organizations such as the right-leaning Chamber of Commerce and the more liberal Institute for American Democracy (IAD) counseled Americans to create private file systems for collecting and collating information on their neighbors. The Chamber advised every local branch to create an elaborate file system to serve as the “eyes of the community” looking for local Communist activities. “If you keep track of the players,” an IAD pamphlet similarly explained, “you quickly learn the score on extremist activity in your community. Files become the garden implements for workers in democracy's vineyard.” The fundamentalist American Council of Christian Churches reminded “re-awakened” college students that “one of the most neglected needs” of young Christians “is an adequate filing system so that information read today can be located when it is needed for documentation tomorrow.”Footnote 68

Industrious amateur investigators developed complex file systems for housing an ever-expanding collection of clippings culled from local and national newspapers, The Congressional Record, and various legislative committee reports. They also bought information and outsourced surveillance to trusted watchers: those with money could purchase preclipped and annotated material. They received national publications such as the Dan Smoot Report, the various periodicals of the John Birch Society, or Stuart McBirnie's Documentation and clipped and indexed the issues to suit their purposes.

Women were especially active watchers.Footnote 69 As Gary North, a Southern California conservative activist, remembered decades later, many of these women belonged to a network of right-wing groups, and they did their research out of a profound sense of patriotic duty. Remembering a close friend of his parents, North recalled in 2002:

She was an inveterate collector of The Congressional Record. She clipped it and lots of newspapers, putting the clippings into files. . . . She was representative of a dedicated army of similarly inclined women in that era, whose membership in various patriotic study groups was high, comparatively speaking, in southern California. These women are dead or dying now, and with them go their files—files that could serve as primary source collections for historians of the era. I suspect that most of them disposed of their collections years ago, cardboard box by cardboard box, when they ran out of garage space, and their nonideological husbands and children finally prevailed.Footnote 70

Historian Michelle Nickerson's study of the political activism of Southern Californian housewives provides a rich narrative capturing the broader cultural context of the kind of surveillance described by North. For example, she observed that the Network of Patriotic Letter Writers, a collective of mostly female activists, “had been monitoring Communism and accumulating files” for much of the 1950s.Footnote 71 As they clipped, attended meetings, and watched their neighbors, the network's files had swelled. Before the end of the decade, the network had to recruit a full-time researcher and rent office space to house their ninety-nine boxes of files.Footnote 72

In churches across the United States, this midcentury investigative spirit helped spur the widespread proliferation of innumerable ad hoc committees, layperson commissions, and informal panels assigned to probe the alleged subversive activities of the NCC. These religious roundsmen patrolled the boundaries of orthodox Protestantism and guarded it against alleged Communist influence. Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, Baptists, and fundamentalists of all descriptions clipped newspapers, read congressional reports, interrogated clergy, wrote their public officials, and assembled their conclusions into reports, memoranda, and presentations at church board meetings and general assemblies.

Although it is difficult to draw concrete conclusions about which American Christians most actively guarded the frontier between religion and Communism, declassified FBI files provide some clues.Footnote 73 The Bureau maintained many domestic security files on issues related to the communist infiltration of religious organizations in the United States. One of the largest, a file of more than 2,400 pages titled “Communist Infiltration of Religion” (file number 100-HQ-403529), recorded the Bureau's efforts to assess the accusations swirling around mainline Protestant denominations, with specific focus on the NCC.Footnote 74 This file collected inquiries from adherents from a variety of denominations, but Protestant mainline churches in the Methodist, Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Congregationalist traditions were the most frequent.Footnote 75 After letters from authors from mainline churches, inquirers from an assortment of unaffiliated and nondenominational Protestant churches and a few nontrinitarian groups, sent the Bureau inquiries.Footnote 76 Regardless of the authors’ denominational affiliations, their letters came from everywhere—from the megalopolises of New England and the mid-Atlantic states, the rural South, small towns in the Midwest, and the burgeoning population centers of the Sunbelt.Footnote 77

These FBI files point to the existence of a nationwide movement of citizens trying to untangle the FCC–NCC–Communism knot. Because many of the church investigators believed they needed a final, trusted arbiter of the facts, they inundated J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI with the letters, charts, and fallacious reports that formed the bedrock of the FBI's own investigations into ecumenical Protestantism. This recursivity pointed to the profound epistemological uncertainty that lay at the heart of the problem. Many of the FBI's correspondents acknowledged that they could not find any factual proof of the NCC's collusion with Communists, but they traced this lack of evidence to the problematic nature of the “facts” themselves. As one correspondent wrote to Hoover, “The officers of the [redacted] Presbyterian Church are trying to make a study of the National Council of Churches . . . . However, we are finding it next to impossible to locate any factual unbiased information in this regard.”Footnote 78

Other investigators believed they had discovered the verifiable “facts” that they sought, only to realize that many in their own congregations refused to accept their “proof.” A Methodist fact-finder noted that his congregation's support for the NCC had prompted “quite a bit of feeling” in the church. Some in the congregation “rely completely on the charges of Edgar C. Bundy and Carl McIntyre [sic]” to condemn the NCC, while other church members rejected the findings of these anti-communist authorities. To settle the matter, the church appointed a committee to investigate the NCC. After some wrangling in the church, the committee concluded that “they have every confidence in anything that” Hoover might say on the matter—so they wrote the FBI director. Another chairman of a similar ten-member Methodist Church committee, which was formed to investigate the NCC, pleaded with Hoover, “Could you please send us information as to where we can get information about this that would be the truth[?]” It is difficult to believe that the FBI's inevitable nonresponses to these inquiries—such as, “I hope you will not infer either that we do or do not have material in our files relating to the [NCC]”—did not strike some readers as the bureaucratic equivalent of Pilate's infamous proto-postmodern rebuke, “What is truth?”Footnote 79

Not all of the investigators approached Hoover in search of more trustworthy information. Some believed they had uncovered the necessary facts to condemn the NCC, and they wrote the Bureau to share their findings. In Admore, Oklahoma, St. Philip's Episcopal Church organized an Americanism Committee to research the NCC. After concluding their investigations, the committee assembled a thirty-four-page booklet titled “A Two Hour Parish Study of Communism and the Episcopal Church.” Confident in their research and its pedagogical utility for other loyal Americans, in 1961, the St. Philip's Episcopalians sent their study course to the HUAC and to Hoover. They hoped that Hoover, like HUAC chairman Francis Walters, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, might do the church the honor of placing the booklet in the FBI's permanent research files. “You are,” they wrote Hoover, “the Moses of today whom the Lord has raised up to lead our people through the wilderness of Communism and onto the promised land, once again, of the sound and solid principles of our Christian American heritage.”Footnote 80 Meanwhile, in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, another Episcopal congregation started a committee they called “Call to Arms.” The committee focused on creating “informed and convinced” Christians who can “conquer the Communist conspiracy even in its floodtide.” The committee, rather than asking Hoover for information, instead asked for his “endorsement” of their research endeavors, which they hoped to publish in the parish magazine. Hoover declined an official endorsement but he commended their focus on becoming “better informed” “through the process of Christian education.”Footnote 81

Almost as frequently as inquiries from official church investigations, letters came from rogue inquisitors seeking information from the FBI to buttress their efforts to police their denominations and challenge dissenting members of their congregations. A Baptist pastor from Wisconsin told members of his church's board that the “American Baptist Convention is Modernistic” and associated with the communistic NCC. When members of the board resisted the pastor's claims, he turned to Hoover for help in clarifying the matter: “Now I realize that this is a strong accusation to make, but I have heard of men in the National Council of Churches that deny God Himself, Jesus Christ, and the Virgin Birth of Christ as well as His atoning death upon the cross. Is not this one of the main doctrines of the Communist Party?” In another case, a member reported that his church's “Social Action and Education Committee” had “investigated” the NCC and concluded that there was “no truth in the charges” against the ecumenical organization. Angered by his fellow committee members’ blithe ignorance to the Communist menace, the writer reached out to the FBI for “conclusive proof that the Protestant churches of America have been infiltrated by the Communists.”Footnote 82 The FBI, as was its wont, refused to comment on the matter.

Conclusion

On May 15, 1956, a Special Agent from the FBI's Washington, D.C., headquarters sat down to interview a woman claiming to have incendiary information regarding Communist efforts to infiltrate the University Congregational Church near the campus of the University of Washington in Seattle. The woman “spoke for approximately 3 hours” with the agent as she recounted a byzantine tale of conspiracy and religious intrigue in which a senior prelaw and psychology major at the University of Washington inquired about becoming a theologian.Footnote 83 Although seemingly unremarkable, the student's banal professional aspirations swelled into something dark and twisted as the woman spoke. According to her story, the student began insinuating himself into church groups around the university. He “appears to be an atheist,” she told the agent, “in that he stresses disbelief in God and the fact that pure science can solve all problems.” Further, a summary of the agent's interview recounted that the student “is critical of the Government, and builds up agitation between the economic classes in all his teachings and is completely negative and depressive.” Parents of other students attending these church groups came to believe their children “seem to be going through a complete ‘brainwashing’” by the aspiring atheist-theologian. The perplexed agent noted that the woman “rambled off in many directions,” and he expressed concern when he found it “difficult to keep her on the subject matter of her main complaint.” As he pressed the woman to keep on task, she produced a “brief case full of newspaper clippings, charts and diagrams and what appeared to be numerous rambling notes.” Confused and likely exhausted by yet one more fevered attempt to map Communist infiltration of a Protestant church, the agent dismissed the woman as “overly alarmed” and concluded the memo by offering no recommendation for further investigative action.

In the end, this bureaucratic oddity—and so many thousands of others like it—came to nothing. For all the attempts by the likes of this would-be informant to chart, index, and archive the Communist threat to America's Protestant churches, the evidence proved stubbornly elusive. In fact, FBI investigators had dismissed the infiltration of Communism in the churches even if the Bureau's public rhetoric still implied the potential of such threats. Internal memoranda produced by J. Edgar Hoover and his agents showed that many of the attacks on the FCC and NCC originated as an internal Protestant fight between rival sects. As early as the mid-1950s, internal FBI documents conceded that nearly all of the “derogatory information” about the FCC and NCC “comes from rival church groups,” especially those from fundamentalist or conservative evangelical backgrounds.Footnote 84

But the FBI's effort to reduce these controversies to interchurch organizational disputes or theological infighting was, at best, a selective and self-serving assessment of the issues involved. At every step, from the end of the First World War to the onset of the Cold War, the federal bureaucracy had played an instrumental role in facilitating a context that framed citizenship, civic voluntarism, and domestic loyalty in terms of resistance to foreign Communism. World War I–era efforts to enlist citizens as voluntary agents of and docile targets for state surveillance meant that average Americans looked for subversion in the institutions that dominated their everyday lives: their schools, workplaces, families, voluntary associations, and their churches. Further, the valorization of business interests in the face of Communist threats tended to make many—but certainly not all—Americans skeptical of labor unions and hesitant to support social projects that emphasized state regulation of economic activity. By the late 1940s, these durable cultural tendencies found an acute expression in the general skepticism of the FCC and, eventually, the NCC. These ecumenical religious organizations—with their historic sympathy with labor unions, Social Gospel–inspired progressivism, and willingness to address controversial issues ranging from civil rights for African Americans to the diplomatic recognition of Soviet Russia—seemed to flirt with the very political, social, and economic projects generations of Americans had been encouraged to distrust. Indeed, as a young bureaucrat in the Justice Department, Hoover had voiced support for Maxwell's early efforts to stoke countersubversive zeal through visual media such as her infamous spider-web chart. This complex cooperation between countersubversive elements in the Justice Department, the military, and a network of business leaders created a framework for visualizing a vast web of subversive agents that expanded to include the largest ecumenical Protestant parachurch organization of the twentieth century.Footnote 85

Although it is easy to dismiss these countersubversive forces—and, by extension, Hoover's thousands of anti-FCC and anti-NCC interlocutors—as engaging in naïve guilt-by-association polemics, the fact is they were part of a more than half-century-long tradition of sophisticated political surveillance and factual fabrication. These activists learned how to identify domestic threats, mastered techniques of sorting and fabricating connections between social actors, and deployed novel visualization and archival techniques for rendering these complex relationships legible to likeminded Americans. In our contemporary moment in which prominent national figures have called for the resurrection of HUAC to monitor the political loyalties of suspect religious populations and in which privately held corporations admit that domestic political surveillance is as important to corporate risk assessment as maintaining tight security protocols, reevaluating the relationship between state and private surveillance networks seems especially salient.Footnote 86 As electronic databases and internet-based social networks replace card indexes and paper-based file systems as ways of knowing the social and visualizing its shape, and as “Sharia law” displaces ecumenical Protestantism as America's next great internal religious threat, new ways of charting social networks and visualizing their political influence are likely to mingle with this much older and durable culture of voluntary domestic religious surveillance.Footnote 87