1. Introduction

Over the last 30 years there have been considerable advances regarding both dictionary content and format. Yet studies into dictionary use show that the spectacular developments that have taken place in the past decades have not had a dramatic impact on actual dictionary-user behaviour (Atkins & Varantola, Reference Atkins and Varantola1997; Frankenberg-Garcia, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2005, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2011; Gromann & Schnitzer, Reference Gromann and Schnitzer2016; Lew & de Schryver, Reference Lew and de Schryver2014; Welker, Reference Welker2006). Dictionaries – both paper-based and digital – remain by and large underused, with the public in general still referring to them mainly for language comprehension, to look up definitions (or translations in the case of bilingual dictionaries), or simply as an authority that can be consulted, often in the contexts of games and crossword puzzles (Müller-Spitzer, Reference Müller-Spitzer2014). Few users are aware that dictionaries can also help in language production, offering users information about how to employ words in texts. As a result, it is widely acknowledged that more needs to be done to teach dictionary consultation skills. The ColloCaid project stems from the realization that an arguably better solution would be to develop alternative, dictionary-like tools that do not require much in the way of training or instruction. In this paper we describe the development of an intuitive lexicographic resource that is accessed from within digital writing environments to help learners write more idiomatically. More specifically, we aim to assist users of English for Academic Purposes (EAP) with collocations.

2. Research background

Much research and development has already been achieved with regard to writing tools. Most text editors today, for example, come with integrated spell checkers and can recognize simple grammatical and stylistic issues, such as capitalization problems and missing punctuation. Some text editors also allow users to right-click on words to retrieve synonyms. Although many of these functionalities can undoubtedly be immensely helpful to writers, the more complex automatic advice given by this kind of software – such as flagging up the use of the passive voice or overly long sentences – is often simplistic and prescriptive.

In addition to text editors, recent advances in computational linguistics and machine learning have enabled researchers to develop novel types of writing assistants. Grammarly, for example, is an online writing platform and plug-in for Microsoft Word that gives general feedback on features such as English spellings, verb tenses, and word choice, with a paid service that enables users to adjust the feedback according to document type (e.g. business emails). Read and Write Gold helps people with dyslexia or other learning difficulties with predictive spelling, word choice, and dictionary and thesaurus features. Cambridge’s Write & Improve gives automatic feedback to writers at different levels of English proficiency when engaging in the set writing assignments specified in the tool. WriteAway autocompletes writers’ sentences with words taken from a corpus. Write Assistant, aimed at Danish users of English, integrates a bilingual Danish-English dictionary and predictive text as an add-in to Microsoft Word (Tarp, Fisker & Sepstrup, Reference Tarp, Fisker and Sepstrup2017).

In this project, we are aiming for a more targeted tool and resource. Rather than attempting to cover every possible writing issue at once, we are focusing on collocations; that is, words that are conventionally used together in a language or specific variety of language. Collocations constitute a particularly pervasive problem in learner and non-expert writing (Boers & Webb, Reference Boers and Webb2018; Nesselhauf, Reference Nesselhauf2005; Paquot & Granger, Reference Paquot and Granger2012; Wray, Reference Wray2013). Violating collocation conventions can result in errors or awkward, non-idiomatic text (e.g. *an increase of temperature; *to make research; *a large mistake). This affects not only writing, but also reading, as texts with collocation problems are known to be more difficult to process (Conklin & Schmitt, Reference Conklin and Schmitt2012; Ellis, Simpson-Vlach & Maynard, Reference Ellis, Simpson-Vlach and Maynard2008).

It would not be feasible, however, to cover every possible collocation in a language. The ColloCaid project aims specifically to help writers with the collocations of academic English. English plays a fundamental role in the dissemination of knowledge (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2014), and focusing on academic English will enable us to develop a writing tool for a well-defined group of real-world users.

The vast number of EAP programmes devoted to helping writers is testament to the significant effort required to master written academic prose. Although in the UK such programmes are usually tailored to meet the specific needs of second language (L2) users of English, in agreement with Kosem (Reference Kosem2010) and Hyland and Shaw (Reference Hyland and Shaw2016), we take the view that there are no native speakers of academic language. This claim is supported by a study comparing the collocations available to first language (L1) and L2 English EAP users across different levels of academic experience, where Frankenberg-Garcia (Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2018) found that academic experience was a better predictor of the number of academic collocations EAP users could employ in gapped academic sentence excerpts than having L1 English.

Although both L1 and L2 English novice EAP users need to familiarise themselves with the collocations they are expected to produce in academic settings, like further research, change substantially, and particularly dramatic, it is important to recognise that the difficulties they will encounter on the way may differ. EAP users with L1s other than English may be hindered by the interference of incongruent collocations in their first languages (Peters, Reference Peters2016), but L1 English EAP users may let themselves be overly influenced by general-English collocations that could sound out of place in more formal academic settings (Frankenberg-Garcia, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2018).

Another point that must be made is that although existing research recognises that there are a good number of collocations that cut across different academic domains (Ackermann & Chen, Reference Ackermann and Chen2013; Durrant, Reference Durrant2016; Gardner & Davies, Reference Gardner and Davies2014; Lea, Reference Lea2014a), EAP users are also required to become acquainted with discipline-specific collocations. For example, compile corpora and parallel concordances are collocations used specifically in the field of corpus linguistics. Hyland and Tse (Reference Hyland and Tse2007) believe a more restricted, discipline-specific lexical repertoire may be preferable from a pedagogical point of view. However, incidental learning of collocations increases in step with the number of encounters with target collocations (Webb, Newton & Chang, Reference Webb, Newton and Chang2013). Thus, as discussed in Frankenberg-Garcia (Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2018), one must consider the possibility that EAP users might end up acquiring discipline-specific collocations more easily throughout a targeted and concentrated exposure to the subject matter of their studies. On the other hand, general academic English collocations could be harder to remember because they are less noticeable to EAP users.

There are a number of tools and resources for learning general EAP collocations. Based on the 25-million-word written component of the Pearson International Corpus of Academic English (PICAE) (Ackermann, de Jong, Kilgarriff & Tugwell, Reference Ackermann, de Jong, Kilgarriff and Tugwell2011), Ackermann and Chen (Reference Ackermann and Chen2013) compiled the Academic Collocations List (ACL), with 2,469 cross-disciplinary collocations that were pedagogically vetted by EAP experts (e.g. abstract concept, briefly describe). Of course, in the same way as people do not learn a language by reading dictionaries, EAP users are not expected to learn EAP collocations by reading through such a list. However, as Swales (Reference Swales2002: 151) explained, vocabulary lists can serve as a “platform from which to launch corpus-based pedagogical enterprises.” The ACL, for example, has been converted to standard dictionary format and appended to the Longman Collocations Dictionary and Thesaurus (Mayor, Reference Mayor2013), which EAP users can consult as they write. In Quizlet, an online platform for creating and sharing educational materials, it is possible to access a series of interactive online exercises such as flashcards and matching quizzes based on the ACL.

Novice EAP users can also learn about academic collocations extracted from corpora by studying from EAP textbooks like Focus on Vocabulary: Mastering the Academic Word List (Schmitt & Schmitt, Reference Schmitt and Schmitt2005) and Academic Vocabulary in Use (McCarthy & O’Dell, Reference McCarthy and O’Dell2008). Another lexical resource EAP users can consult is the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary of Academic English (Lea, Reference Lea2014b), which was informed by the Oxford Corpus of Academic English (OCAE), and whose accompanying CD-ROM includes interactive collocation exercises.

The Louvain EAP Dictionary (Granger & Paquot, Reference Granger and Paquot2015), in turn, is a corpus-based free resource initially developed for University of Louvain users that has recently been opened to the wider community. It provides collocations, corpus examples, and translations (into French) for circa 1,200 academic headwords. Another free, online EAP collocation resource is the FLAX Library, which provides easy online access to collocations in the British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE) (Nesi, Reference Nesi2011).

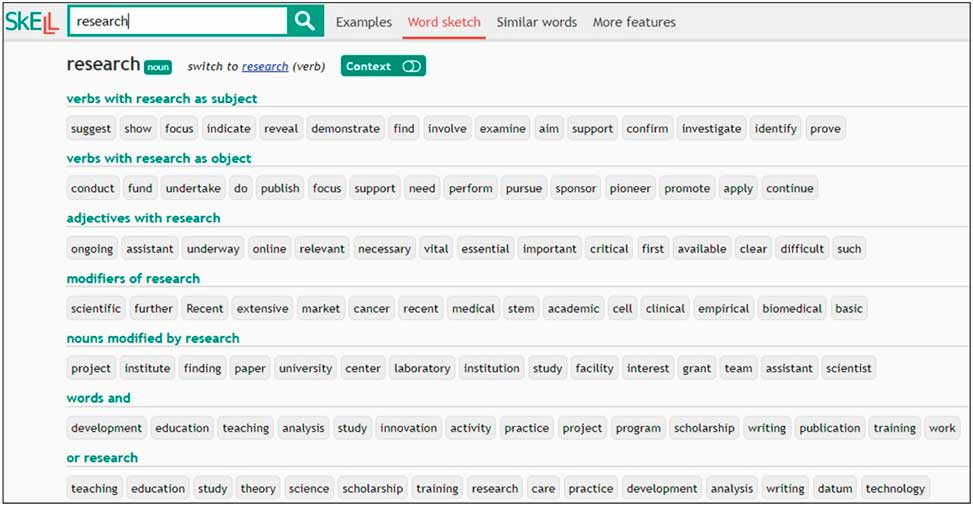

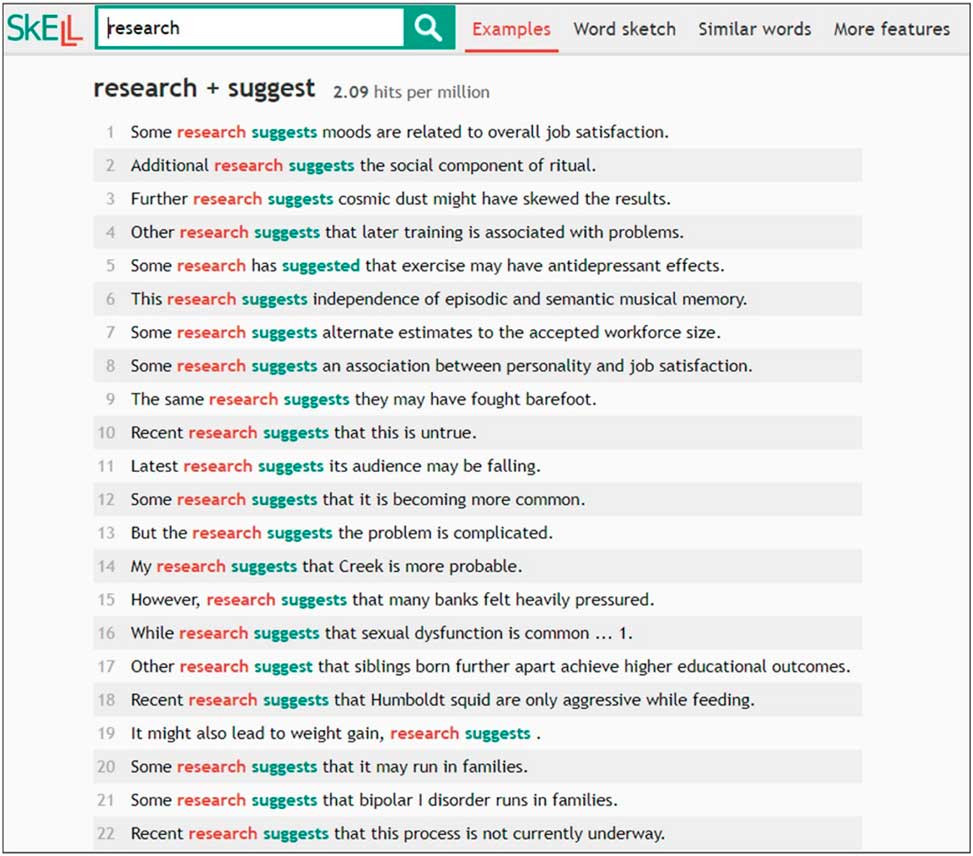

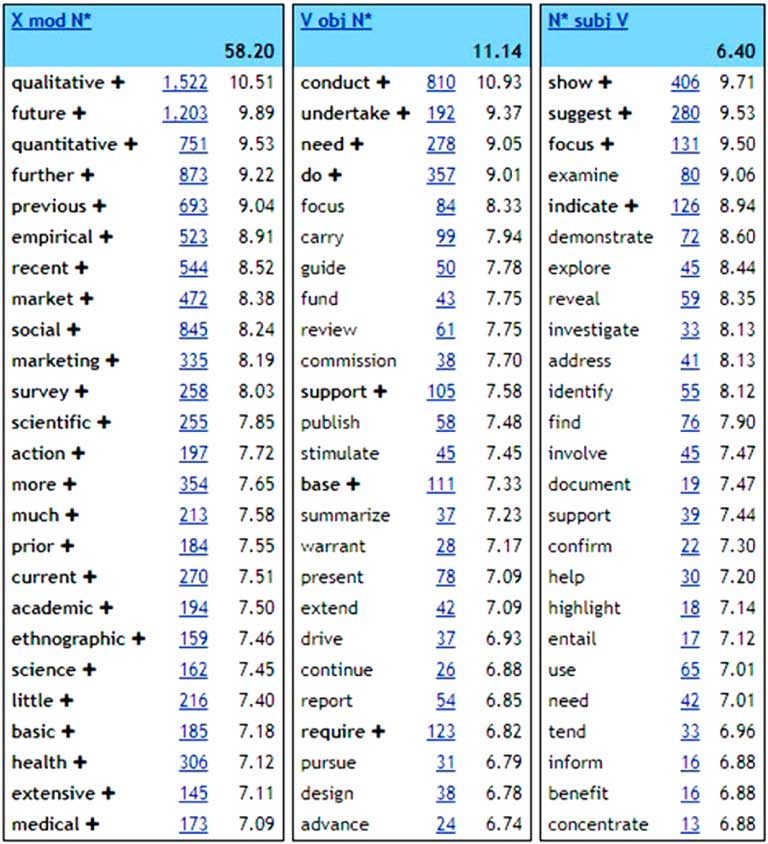

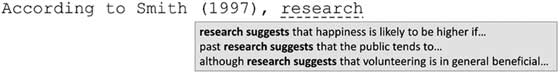

Although there is no room here to carry out an exhaustive review of existing EAP collocation aids, one last resource that deserves to be highlighted is Sketch Engine for English Language Learning, or SkELL (Baisa & Suchomel, Reference Baisa and Suchomel2014), an open-access tool to help laypeople not familiar with corpora better understand how words are used in English. Although SkELL is based on a corpus of general rather than academic English, looking up academic words in SkELL’s word sketch option is likely to return academic collocations, as exemplified in Figure 1 with a word sketch for research.Footnote 1 Clicking on a specific collocate will then bring up 40 concordance lines illustrating how to use the selected collocation in context, as shown in Figure 2 for the collocation research+suggest. The resulting concordances are automatically selected such that priority is given to “sentences with more frequent words, filtering out effectively all sentences with special terminology, typos and rare words” (Baisa & Suchomel, Reference Baisa and Suchomel2014: 69). What is particularly appealing about SkELL is that its extremely user-friendly and intuitive free online interface allows people who have never heard of corpora to benefit from a one-billion-word pedagogically motivated general English corpus tool.

Figure 1 Word sketch for research in SkELL

Figure 2 Concordances for research + suggest in SkELL

However valuable all these collocation resources may be, as previously discussed, most language users are not in the habit of consulting references to help them in language production. Moreover, in the specific case of collocations, Laufer (Reference Laufer2011) found that learners tend to overestimate their knowledge, so do not feel the need to look them up in the first place. Even if EAP users were made aware of their shortcomings and got used to turning to collocation dictionaries and other resources, the fact that they have to interrupt their writing to look up a collocation can disrupt the flow of their words. As Tarp et al. (Reference Tarp, Fisker and Sepstrup2017: 496) explained, “any consultation of an external information resource inevitably represents an interruption of the activity in question,” and if users get distracted in the process (by online ads, for example), “when they finally return to the task they were performing they will probably have lost their focus and maybe even forgotten why they started the consultation in the first place.” This can be especially detrimental to the cognitively demanding process of academic writing.

We therefore propose to develop a tool to help EAP writers with academic collocations directly from within a text editor in a way that does not distract them from their writing. In the sections that follow, we explain the rationale underpinning (1) the lexicographic database we are compiling to support novice EAP users’ general academic English collocation needs and (2) the preliminary visualisation decisions taken to present writers with information on collocation as seamlessly as possible. We conclude the paper by outlining the next steps in our research.

3. Lexicographic decisions

As discussed in the previous section, we believe it is possible to arrive at a core set of collocations that can benefit novice EAP writers in general, irrespective of first language or subject specialism. This section describes the lexicographic decisions made in the process of developing ColloCaid. It begins by explaining how previous research to identify core academic vocabulary was used to determine which collocation nodes to prioritise. Next, it outlines how expert academic English corpora were used to compile a database of collocations and corpus-based examples to support novice EAP users.

3.1 Collocation nodes

To maximize the relevance of the EAP collocation support offered by ColloCaid, academic vocabulary frequently used across disciplines was taken as a starting point to determine which collocation nodes to focus on. A combination of three recognised EAP vocabulary lists was used for this purpose. The first one was the Academic Vocabulary List (AVL; Gardner & Davies, Reference Gardner and Davies2014), which consists of 3,000 core lemmas that occur across a range of academic disciplines in the 120-million-word academic subcorpus of the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies, Reference Davies2008). Although COCA is an American corpus and the spellings in AVL favour American English conventions (e.g. analyze, not analyse), the vocabulary listed is based on texts by an international community of experts. An advantage of the AVL is that, as discussed in Gardner and Davies (Reference Gardner and Davies2014), it addresses known limitations of the well-established Academic Word List devised by Coxhead (Reference Coxhead2000) more than 10 years earlier.

Not all academic lemmas trigger relevant collocation questions, however. It would not make sense for a writer to initiate a collocation query from an adverb (e.g. “what words can I use with primarily?”). Therefore, when considering which collocation nodes to focus on, the 283 adverb lemmas in AVL were not taken into account. Even without the adverbs, however, it would not be feasible to construct a lexicographic database with the over 2,700 remaining noun, verb, and adjective lemmas in AVL within the scope of the present, three-year project. Moreover, as AVL is based on expert academic writing, novice EAP users may simply not use some of the core academic lemmas in the list, so there would be no point in helping them find collocates for words that they did not use in the first place. In fact, in a study investigating the extent to which AVL words were actually employed in university student writing from the BAWE corpus, Durrant (Reference Durrant2016) found that around half the lemmas in the list were rarely used, and that frequent items were not always well distributed across disciplines. Durrant was nevertheless able to identify 427 AVL items in BAWE that were both frequent and used in over 90% of the disciplines. This included 38 adverbs (e.g. however, therefore), which, as discussed above, were not considered relevant to our research. The remaining 174 nouns, 136 verbs, and 79 adjectives identified by Durrant (henceforth referred to as AVL-BAWE) were, however, regarded as central to the compilation of the ColloCaid database.

It was nevertheless deemed important to validate and, if relevant, expand the AVL-BAWE selection using additional corpus-based EAP vocabulary lists extracted from other corpora. One such source was the Academic Keyword List (AKL), developed by researchers at the Université catholique de Louvain and used to inform both the previously referred to Louvain EAP Dictionary and the academic writing section of the Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (Rundell, Reference Rundell2007). The AKL was compiled by extracting keywords from expert British EAP corpora (the academic sections of the British National Corpus [BNC] and Micro-Concord) and a corpus of British and American student written assignments (Louvain Corpus of Native English Essays [LOCNESS] and BAWE) using a large reference corpus of fiction for contrastive purposes (Paquot, Reference Paquot2010). It consists of 930 items, of which 766 (353 nouns, 233 verbs, and 180 adjectives) would be useful to cross-reference with AVL-BAWE.

The third and last corpus-based EAP source used to determine which collocation bases to cover in ColloCaid was the previously referred to ACL (see section 2). The ACL is different from the two previous lists because, rather than individual lemmas, it presents collocation units (e.g. abstract concept). Although it may be suitable to cover such units in textbooks and flashcards for studying academic vocabulary, they are less useful at the moment of writing, as writers tend to ask questions like, “what adjective can I use with concept?” rather than “where in my text can I fit in abstract concept?” The way we incorporated the ACL in our research was by referring to the appendix of the Longman Collocations Dictionary and Thesaurus, where the ACL is conveniently itemised as 705 separate collocation-node entries (526 nouns, 96 verbs, and 83 adjectives).

Because of the very method of extraction underlying them, we know ACL nodes are bound to evoke strong collocations, unlike the lemmas in the previous two lists, whose significance is due to their individual occurrences rather than their collocational behaviour. However, unlike AVL-BAWE and AKL, the corpus underlying ACL did not cover student writing, and the collocations in ACL exclude the general English words in West’s (Reference West1953) General Service List, some of which (e.g. table) can be very relevant in academic texts. By combining the three lists when determining which collocation bases would be considered for inclusion in ColloCaid, we hope to build on the strengths of each of them. Table 1 summarizes how the three vocabulary lists overlap.Footnote 2 Unsurprisingly, given its extraction method, ACL stands out as different, with comparatively more nouns and fewer verbs and adjectives. As shown in Table 1, the 187 lemmas attested in all three lists were prioritised in ColloCaid, but the 282 nouns, 136 verbs, and 94 adjectives attested in at least two of the lists were taken also into account (see Appendix).

Table 1 EAP collocation node selection in ColloCaid

* Academic Vocabulary List (Gardner & Davies, Reference Gardner and Davies2014) lemmas frequent in student writing (Durrant, Reference Durrant2016).

ǂ Academic Keyword List extracted from expert and learner EAP corpora (Paquot, Reference Paquot2010).

ɸ Academic Collocation List (Ackermann & Chen, Reference Ackermann and Chen2013) headwords in Longman Collocations Dictionary and Thesaurus.

The final decision regarding which of the 513 core academic lemmas listed in the Appendix will be included in ColloCaid will ultimately depend on their collocational behaviour. For example, the adjective actual is not collocationally productive, so it is not useful to cover it. On the other hand, lemmas with more than one sense in academic English – like subject (participant) and subject (discipline) – will be considered separately.

3.2 Collocates and examples

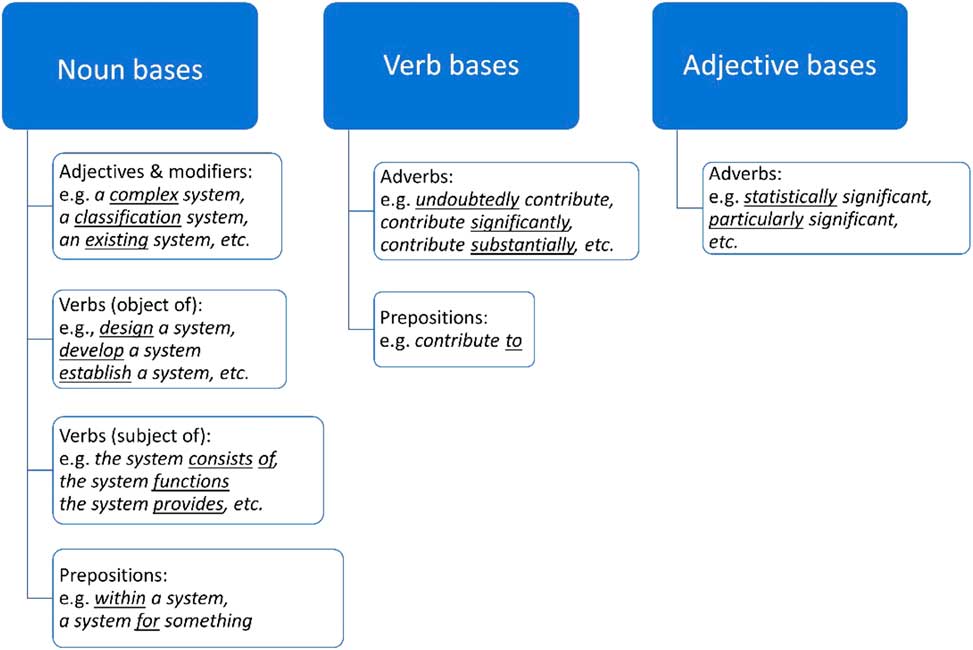

Having determined which collocation nodes to focus on, we followed the pragmatic approach used in collocation dictionaries to establish which collocates to present under each node, bearing in mind that different part-of-speech categories trigger different collocation questions. For example, it is more likely that writers will take a noun like research as a starting point and want to look up a verb to go with it (e.g. carry out) than start from a verb like carry out and look up a noun to go with it. Thus, the collocates presented to the user depend on the logical collocational paradigms they evoke, as exemplified in Figure 3. As can be seen, both lexical and grammatical collocates were considered. Note that under noun bases, verbal collocates where the noun is the subject of the sentence are analysed separately from verbal collocates where the noun is the object, as they represent different paradigms in the minds of writers.Footnote 3 Figure 3 also indicates that adverbs are shown before or after the verb, depending on which is more frequent, and that noun bases tend to be collocationally more productive than verb and adjective bases.

Figure 3 Examples of collocation nodes and collocates evoked

Having defined the type of collocations we aimed to provide, the next step was to populate our database of selected collocation nodes with collocates to support novice EAP users. Although it had been important to consider corpora of student writing to make sure appropriate coverage was given to words novice EAP writers actually use (and which therefore have the potential to prompt collocation queries or problems), when investigating the collocations associated with the lemmas selected it made sense to use expert academic writing as a benchmark.

Several professional written academic English corpora could be used for this purpose. In addition to open-access resources like the academic components of COCA and the BNC, permission was obtained to use PICAE and OCAE (see section 2). We opted to prioritise the use of OCAE, but used the other three corpora to obtain supplementary data when required. With around 70 million words of expert academic writing from a range of disciplines published in journals and textbooks between 2000 and 2011, OCAE was the largest corpus of written academic English available to us in Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff et al., Reference Kilgarriff, Baisa, Bušta, Jakubíček, Kovář, Michelfeit, Rychlý and Suchomel2014), the state-of-the-art corpus-processing tool we elected to use in this research.

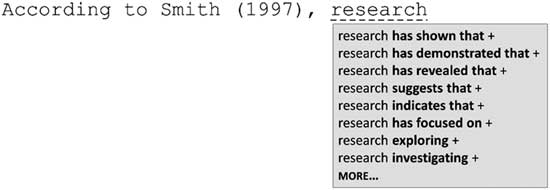

Sketch Engine’s word sketch function (previously shown in Figure 1) greatly facilitates the task of analysing collocations by sorting collocates according to their grammatical relations with the node. Whereas the word sketch for research from SkELL in Figure 1 is presented in a simplified format for laypeople, a snapshot of an expert-user word sketch for research from OCAE is displayed in Figure 4. Its flexible set-up allows users to choose how many and which grammatical relations to view (only three grammar relations are shown in Figure 4), and how much data is presented under each category (the settings can be altered to view more or fewer collocates). The numbers next to each collocate refer to frequency of co-occurrence (first number) and the logDice score (second number). They show how many times a collocate appears in the immediate context of the node (e.g. there are 1,522 occurrences of qualitative+research), and the strength of association measure used to establish whether combinations of words in a corpus can be considered collocations (e.g. the logDice score for qualitative+research is a very high 10.51). Although there are other measures for computing strength of association, the logDice statistic favoured in word sketches (Rychlý, Reference Rychlý2008) is more robust than the t-score (which is overly sensitive to high-frequency words), and more appropriate than the MI score (which rewards low frequency items, including very rare or even misspelled words) (Frankenberg-Garcia, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2018). According to Gablasova, Brezina and McEnery (Reference Gablasova, Brezina and McEnery2017: 164), logDice “highlights exclusive but not necessarily rare combinations,” which was exactly what we felt was important to offer in a tool to assist writers with collocation.

Figure 4 Word sketch for research in OCAE

Although it would be possible to simply link word sketches to a text editor, our aim was to develop an integrated tool that would enable EAP users to concentrate fully on their writing, without any distractions from the potentially dirty or noisy data inherent to corpora. We therefore opted to curate the collocation information retrieved from OCAE. When selecting which collocates to present under each collocational paradigm, we chose to present only collocations used across different academic disciplines. This leaves more room for supplying more collocations that are useful to EAP users in general and at the same time prevents writers from being distracted by subject-specific collocations that are irrelevant to them. Moreover, as discussed earlier, we believe discipline-specific collocations are easier for EAP users to acquire incidentally, through concentrated exposure to the subject matter of their studies, hence the focus on interdisciplinary academic collocations. Thus, of the modifiers of research shown in Figure 4, we considered collocations like qualitative/future research, but not market/social research. It is usually straightforward for an experienced lexicographer to tell the difference between the two, but whenever doubt arose, it was possible to examine the dispersion of a collocation across different subject areas to determine whether it met the interdisciplinarity criterion. More specifically, we determined the collocation had to be reasonably frequent in at least three of the four broad subject areas in OCAE (humanities, life sciences, physical sciences, and social sciences).

Another decision taken was to group together broadly similar collocates whenever possible. For example, in the case of the modifiers of research shown in Figure 4, qualitative/quantitative/empirical research were placed in one broad semantic group (type), and future/further/previous/recent research in another one (time). It was felt that presenting them in this way could make it easier and faster for writers to retrieve the exact collocate they needed.

However, if necessary, it was also important to be able to help undecided writers discriminate between semantically similar collocations (e.g. future/further research) or simply decide whether a given collocation would be a good match for the context in which it was needed. Following user studies on the value of examples for language production (e.g. Frankenberg-Garcia, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2014, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2015), we opted to do this by presenting writers with carefully curated corpus examples. We were guided by the principles discussed in Atkins and Rundell (Reference Atkins and Rundell2008), where good examples are typical, informative, intelligible, and not overly long. Using Sketch Engine’s GDEX (Good Dictionary Examples) parameters (Kilgarriff, Husák, McAdam, Rundell & Rychlý, Reference Kilgarriff, Husák, McAdam, Rundell and Rychlý2008), it was possible to automatically filter out overly long concordances and concordances containing obscure, low-frequency words so as to make the subsequent manual selection process more efficient. Following findings reported in Frankenberg-Garcia (Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2014, Reference Frankenberg-Garcia2015) that one example alone may not be sufficient to aid language production, we opted to provide three analogous examples for each collocation. However, in order not to distract writers with unnecessary reading nor occupy too much space when evoked on the screen of a text editor, we preferred short excerpts rather than full sentences, as shown in the following examples for future and further research from OCAE (see also section 4):

future research should explore the nature of such associations future research should continue to test a variety of methods to an important area for future research

this last point certainly deserves further research further research is needed to examine how best to … further research is required to address some of these questions

Where relevant, the examples selected were curated so as to purposefully expose writers to further collocations (e.g. further research + needed/required) and colligation (e.g. future research + should). If appropriate, we also strove to present collocations in the context of different grammatical paradigms (e.g. carry out research; research carried out) so as to increase the chances that one of them could be transposed directly to the user’s text. Whenever examples happened to include references to scholarly work, these were anonymised and at the same time shortened by replacing author names and publication dates with citations in random number format (e.g. recent research by [3] has shown that …).

At this juncture, it is important to acknowledge that there are practical limits to the amount of lexicographic data that can be curated in this way within the scope of the present three-year project. Bearing in mind that certain collocation nodes – especially noun bases – can be extremely productive, evoking several dozens of collocates, realistically speaking we could either provide a more comprehensive coverage to fewer nodes or cover more nodes in less detail.

To maximise the usefulness of ColloCaid, our approach to selecting the amount of information to provide was a layered one. We opted to address all the circa 500 nodes listed in the Appendix, but to limit the level of lexicographic curation offered. An investigation of what could be a reasonable cut-off point to determine how many collocates to provide under each collocational paradigm was conducted by inspecting the word sketches for a selected sample of high and low frequency noun, verb, and adjective nodes. In consultation with an EAP expert, a threshold of logDice ≥ 5 combined with a minimum co-occurrence frequency of 10 (0.12 per million) in OCAE was found to work well for lexical collocations. Below that point, relevant collocates were few and far between, and intuitively sounded more like free associations than collocations. For grammatical collocations (i.e. nouns plus prepositions and verbs plus prepositions), the co-occurrence threshold was raised to a minimum of 100 (1.2 per million), given the pervasiveness of grammatical words.

For the more prolific collocation nodes, the list of relevant collocates above the established thresholds could still be quite extensive. For example, there are over 20 interdisciplinary adjectival collocates for research with logDice≥5 and co-occurrence≥10 in OCAE. Therefore, in cases where there was a large number of collocates that met our criteria, our layered approach involved fleshing out with curated examples only the eight strongest collocations under each paradigm (see also section 4), and then listing the remaining collocates without examples. We will nevertheless link the latter to non-curated concordances from an external resource like SkELL. By the same token, we will link lemmas that are not covered in our database of circa 500 to an external resource, which can eventually assist users in situations where ColloCaid cannot.

4. Visualisation decisions

In this section we describe the visualisation decisions we have taken in the conception of our initial prototype. Our guiding principles were

1. To raise awareness of collocations EAP users may not remember to look up (rather than just correcting miscollocations reactively);

2. Not to overburden users with information on collocation, but to allow them to retrieve collocation cues as and when needed;

3. To present this information in an intuitive way so that training is minimal or unnecessary;

4. To provide this information in an unobtrusive way, so as not to disrupt writing processes;

5. To enable users to adjust default settings according to their individual needs.

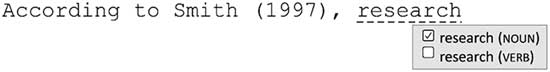

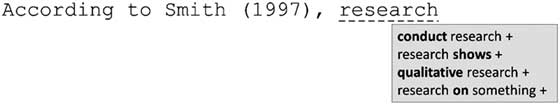

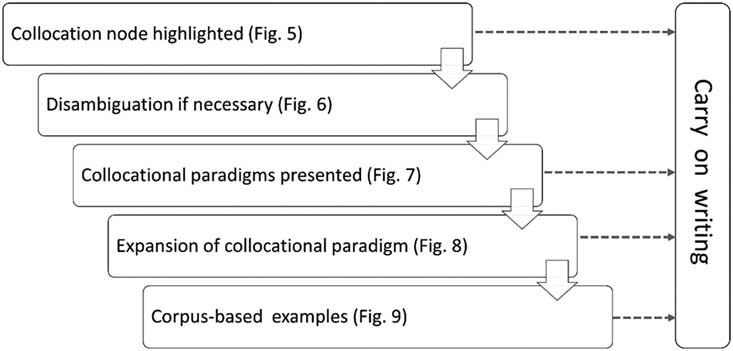

Our first concern was to find an inconspicuous way of letting users know that ColloCaid offered information on collocation for certain words that they might wish to follow up to improve the idiomaticity of their texts. Although there are situations where EAP writers may deliberately pause to try and retrieve a specific collocation (e.g. “what verb can I use with research?”), as discussed in section 2, novice writers tend to overestimate their knowledge of collocations. We therefore wanted users to be able to not only initiate collocation queries, but also to notice collocations they may not otherwise remember to look up. We chose to nudge writers in this direction by highlighting in real time any lemmas they typed that were part of our list of collocation nodes, as shown in Figure 5. Thus, the minute users press the space bar after research, the word is discreetly highlighted to indicate collocational information about the lemma is available. Users can then choose to ignore the prompt and simply carry on writing, or click on the highlighted word to obtain further information. Should they choose the latter, the next step for a lemma like research, which can be a noun or a verb, will be for users themselves to disambiguate the word (see Figure 6). This step will obviously only apply to a limited number of collocation nodes. Rather than introducing on-the-fly part-of-speech tagging, which would not only slow down response time but also be prone to error due to the complexities of parsing unfinished sentences, it would take just a click for users to disambiguate. Similar prompts will also appear whenever it is necessary to disambiguate polysemous nodes, like subject (participant) and subject (discipline).

Figure 5 Highlighting collocation information is available

Figure 6 Disambiguating homographs

If users select the noun, they will then be presented with the collocational paradigms available for it, as shown in Figure 7. Rather than using metalanguage such as adjective+research, research+preposition, which could be off-putting to less linguistically aware users, we opted to present users with the strongest collocate representing each paradigm. This had the additional advantage that users can find what they are looking for there and then and proceed with their writing without having to interact with the tool further. Should users not find the collocate they need, or should they wish to explore further, they can click on one of the plus signs to request more collocates pertaining to the selected collocational paradigm.

Figure 7 Collocational paradigms for research (n)

Figure 8 exemplifies the expansion of the lead collocation research shows. Although electronic resources do not have the same space restrictions as printed collocation dictionaries, which means that for prolific collocation nodes it would be possible to present users with long lists of collocates, invoking too many collocations from within a text editor would not only clutter the main writing screen but also be distracting to the writer. It is important to acknowledge that no matter how fascinating collocations are to a lexicographer or linguist, a writer’s main goal is not to browse collocations, but to find suitable words to convey their thoughts. Therefore, whenever the number of interdisciplinary collocations under a given paradigm exceeded eight, we opted to present at this point only the eight top collocates (in terms of logDice score). We did not want to overburden writers with more, given the well-known limitations as to the number of items that can be processed in the working memory (Miller, Reference Miller1956). Should these first eight collocations not meet the user’s needs, the remaining collocates that satisfy the threshold specified in section 3.2 can be displayed in a side bar by clicking on more. As previously discussed, we will not curate examples for these further collocates but will link them to an external resource like SkELL.

Figure 8 Expansion of collocational paradigm research+shows

Figure 8 also shows that broadly similar collocates have been grouped together to help writers to retrieve the exact collocate they need more efficiently (see section 3.2), and that the collocations are inflected according to typical colligational patterns associated with them, which should increase the chances of users transferring them directly to their emerging texts. When this information is not sufficient, to help undecided writers discriminate between semantically similar collocations or simply give more details about how a given collocation is typically used in context, in the next interaction users can click on the plus sign to retrieve three corpus-based examples curated to provide cues about further collocational and colligational patterns where relevant (see section 3.2).

As shown in Figure 9, research + suggests is often followed by expressions like likely, tend to, and in general, which attenuate the degree of certainty of what is being stated. It can also be seen that the target collocations within each example are highlighted, following research showing that typographically enhanced collocations facilitate intake (Choi, Reference Choi2017; Dziemianko, Reference Dziemianko2014; Szudarski & Carter, Reference Szudarski and Carter2016).

Figure 9 Corpus-based examples for research+suggests

The above choices demonstrate that our approach to visualising collocations enables users to get as much or as little information as they want from ColloCaid. They can choose to ignore the initial highlighted collocation node and simply carry on writing, or, as summarised in Figure 10, they can obtain further information on the collocations associated with a given node incrementally, so that they are not overburdened with too much lexicographic information at once (as is often the case when looking up collocations in dictionaries), and can direct their lookups to the exact information they seek.

Figure 10 Incremental display of collocation information

In addition to this, it is possible for users to customise the visualisation prompts in ColloCaid according to their individual needs. They will be able to switch off real-time help and check their texts only when they wish, and will be able to activate or deactivate specific collocation prompts.

Having laid out our preliminary visualisation decisions aimed at enabling writers to access the collocations they need as seamlessly as possible, without distracting them from their writing, these will be re-evaluated once we start testing the usability of ColloCaid with end users, as explained in the next section.

5. Future work and conclusion

The previous sections detailed the lexicographic coverage and primary visualisation decisions taken in the development of ColloCaid. The next steps in our research involve (1) expanding our lexicographic database to address feedback on miscollocations and (2) collaborating with end users and developers to facilitate and enhance appropriate design solutions and computing prototypes.

To address the first point, we shall scrutinise collocation issues reported in existing work on academic English and learner language as well as use academic learner corpora to investigate whether the core collocation nodes we are focusing on evoke discrepant usages that merit special attention (i.e. error, overuse or underuse of certain collocations). For example, preliminary data from BAWE shows that novice EAP users have problems distinguishing between based in (somewhere) and based on (something), and tend to overuse a lot and lots of. We are also looking to develop collaborations with researchers using EAP learner corpora of different L1s to customize ColloCaid for specific groups of users.

With regard to the second point, in order to fine-tune the ways in which users interact with the system at an early stage, while lexical coverage is still inevitably limited, we are developing an evaluation task that hinges on a predictable set of collocations, but which is nevertheless representative of the type of tasks EAP writers have to complete. Usability tests will be conducted using mixed methods (e.g. protocol analyses, screen recording, and interviews) to elicit reactions from end users and using the five design-sheet method (Roberts, Headleand & Ritsos, Reference Roberts, Headleand and Ritsos2016) to capture specific design requirements.

Although ColloCaid is still under development, we believe our review of previous work and discussion of the decisions taken so far have raised important questions about the usability of lexicographic resources and writing assistants in general, and integrating information on collocation for EAP users with digital writing environments in particular.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), UK, ref. AH/P003508/1.

Ethical statement

The ColloCaid project has received a favourable review from the University of Surrey Ethics Committee. This part of the research is based on publicly available vocabulary lists that draw on anonymised corpus data.

Author ORCIDs

Author ORCiD. Ana Frankenberg-Garcia, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9623-7990

Author ORCiD. Robert Lew, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6772-210X

Author ORCiD. Jonathan C. Roberts, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7718-3181

Author ORCiD. Geraint Paul Rees, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9204-8073

Author ORCiD. Nirwan Sharma, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6576-3848

Appendix

Core academic lemmas considered for inclusion in ColloCaid (priority lemmas in bold)

NOUNS

ability, absence, access, account, achievement, act, action, activity, advance, advantage, aim, alternative, amount, analysis, application, approach, argument, aspect, assessment, assistance, association, assumption, attempt, attention, attitude, author, awareness, basis, behaviour, belief, benefit, capacity, case, category, cause, centre, challenge, change, characteristic, choice, circumstance, class, code, colleague, combination, communication, community, comparison, complexity, component, concentration, concept, concern, conclusion, condition, conflict, consensus, consequence, consideration, constraint, contact, context, contrast, contribution, control, core, correlation, country, crisis, criterion, culture, damage, data, debate, decision, definition, degree, demand, description, design, development, difference, difficulty, dilemma, dimension, discrimination, discussion, distinction, distribution, diversity, effect, element, emphasis, environment, error, evaluation, examination, example, exception, exclusion, existence, expansion, experience, experiment, explanation, extent, factor, failure, feature, figure, finding, force, form, function, group, growth, guidance, history, identity, image, impact, implication, importance, improvement, increase, indication, individual, influence, information, insight, institution, integration, interaction, interest, interpretation, intervention, introduction, investigation, isolation, issue, knowledge, lack, learning, level, likelihood, limit, limitation, link, literature, logic, majority, material, meaning, means, measure, medium, member, method, minority, model, movement, nature, need, network, norm, number, objective, observation, opportunity, organisation, origin, outcome, part, participant, pattern, percentage, perception, performance, period, perspective, phase, phenomenon, point, policy, population, position, possibility, potential, practice, presence, pressure, principle, problem, procedure, process, product, production, programme, progress, property, proportion, protection, provision, purpose, quality, question, range, rate, reality, reason, recognition, reduction, reference, relation, relationship, report, requirement, research, resource, response, restriction, result, review, risk, role, rule, sample, scale, scheme, science, scope, section, sense, service, set, sex, shift, significance, situation, skill, society, solution, source, space, standard, statistics, strategy, stress, structure, study, subject, success, summary, support, survey, system, target, task, technique, technology, tendency, term, theme, theory, tool, topic, tradition, transition, trend, type, understanding, unit, use, value, variation, variety, version, view, volume, whole, work, world

VERBS

accept, account, achieve, acquire, adapt, adopt, affect, aid, alter, analyse, apply, argue, arise, assess, assign, associate, assume, attempt, base, characterise, choose, cite, compare, comprise, concern, conclude, conduct, confine, connect, consider, consist, construct, contain, contribute, control, correspond, create, define, demonstrate, depend, derive, describe, design, determine, develop, differ, discuss, display, distinguish, distribute, divide, effect, emphasize, employ, enable, encounter, encourage, enhance, ensure, establish, evaluate, evolve, examine, exist, expand, experience, explore, express, extend, focus, form, function, generate, govern, highlight, identify, illustrate, imply, improve, include, incorporate, increase, indicate, influence, inform, initiate, integrate, interpret, involve, lack, limit, link, locate, maintain, measure, note, obtain, occur, outline, perform, permit, predict, present, produce, promote, propose, provide, publish, receive, recognize, reduce, refer, reflect, regard, relate, rely, remove, report, represent, require, respond, restrict, result, retain, reveal, seek, select, state, suggest, summarise, support, tend, transform, treat, use, vary, view

ADJECTIVES

acceptable, accessible, actual, acute, additional, alternative, apparent, appropriate, available, basic, central, clear, common, competitive, complex, consistent, correct, critical, dependent, different, direct, distinct, effective, efficient, equal, essential, evident, excessive, explicit, fixed, following, future, general, high, human, ideal, identical, important, increasing, independent, individual, influential, initial, internal, likely, limited, low, minor, modern, natural, necessary, negative, new, obvious, overall, particular, positive, potential, practical, precise, present, previous, primary, recent, relative, relevant, responsible, selective, separate, significant, similar, simple, social, specific, stable, standard, subsequent, substantial, successful, sufficient, suitable, surprising, total, traditional, true, typical, unique, unlikely, useful, valid, valuable, various, vital, widespread

About the authors

Ana Frankenberg-Garcia is a Reader in Translation Studies at the University of Surrey, UK. Her research focuses on applied uses of corpora in lexicography, language learning, and translation. She compiled the COMPARA corpus, was Chief Editor of the Oxford Portuguese Dictionary, and is currently Principal Investigator of the ColloCaid project.

Robert Lew is a Professor at the Department of Lexicography and Lexicology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. His current research interests centre around dictionary use. He has worked as a practical lexicographer and is the Editor of the International Journal of Lexicography.

Jonathan C. Roberts is a Professor of Visualization at Bangor University. His research covers interactive visualization, visual analytics, design of visualisations, and immersive visualization. Much of his research has been to investigate alternative representations of different data sets. It is interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary, including digital humanities, education, oceanography, archaeology, and heritage.

Geraint Paul Rees is a Research Fellow in Corpus-Based Lexicography and Academic Writing at the University of Surrey, UK. His research interests include corpus linguistics, EAP lexicography, and language testing. He has taught on academic and general English programmes in Colombia, Vietnam, and Spain.

Nirwan Sharma is a Research Officer in Human-Computer Interaction and Visualization at the School of Computer Science, Bangor University, UK. He has research interests in citizen science and human-computer interaction.