INTRODUCTION

The 3rd millennium cal BC—referred to as Late Eneolithic or Early Bronze Age in different local research traditions—is a key period in Mediterranean and European prehistory, during which major transformations took place as evidenced by the development of extensive interaction networks. In the Balkans, this process is materialized by a complex archaeological record where various traits and practices are distributed over extended areas linking together different cultural spheres with, on the one hand, the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean, and, on the other hand, the Carpathian Basin and Central Europe. For instance, two-handled beakers—vessels with a variety of morphologies with two high-swung vertical handles—appear in an area extending from Transdanubia to continental Greece during a period spanning the mid-3rd to early 2nd millennium BC (Garašanin Reference Garašanin and Benac1983: 720–722; Stojić Reference Stojić1996: 248; Roman Reference Roman2006: 459; Bulatović and Stankovski Reference Bulatović and Stankovski2012: 323–326; Gori Reference Gori, Gimatzidis, Pieniazek and Mangaloğlu-Votruba2018: 399–404). Roughly at the same time, the Cetina phenomenon is defined by the presence of particular ceramic style and archaeological features from Dalmatia over the entire Adriatic-Ionian area during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC (Govedarica Reference Govedarica1989; Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher2018a, Reference Forenbaher2018b). Further evidence from ceramic assemblages suggests also connections between these two groups (see below).

Although great emphasis has always been given to Mediterranean patterns of sea-borne connectivity (e.g. van Dommelen and Knapp Reference van Dommelen and Knapp2010; Broodbank Reference Broodbank2013), new data and analyses are increasingly demonstrating that overland connections were not only closely intertwined to maritime routes, but that they played a primary role in the development of 3rd millennium cal BC societies (e.g. Maran Reference Maran1998; Gori Reference Gori2020).

In the central Balkans, defined as the region comprising the central part of present-day Serbia (with the exclusion of Vojvodina, which lies in the southern Pannonian plain), the northern part of North Macedonia, and western Bulgaria (Cvijić Reference Cvijić1922), our ability to identify and trace such distant connections relies primarily upon intricate typological debates, associated with potentially circular arguments and confusing, conflicting local terminologies. For instance, despite differences in detailed sub-divisions, there is a general agreement that the Early Bronze Age in Bulgaria lies between the middle of the 4th and the end of the 3rd millennium cal BC (Leshtakov Reference Leshtakov1992; Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999; Todorova Reference Todorova2003), and in continental Greece between 3100 and 2000 cal BC (Manning Reference Manning1995; Rutter Reference Rutter2001; Wiencke Reference Wiencke2000; Arvaniti and Maniatis Reference Arvaniti and Maniatis2018); yet, in Serbia the start of this period is traditionally placed at the end of the 3rd millennium cal BC, following Reinecke’s chronology of the Central European Bronze Age (Reinecke Reference Reinecke1902; Garašanin D. Reference Garašanin1967). Whilst, in the first two areas, the chronological systems are internally coherent and based upon—admittedly limited—radiocarbon dates (e.g. Boyadziev Reference Boyadziev, Bailey and Panayotov1995), they present noticeable discrepancies with Serbia, despite marked similarities in the archaeological record. The chronological position of the Early Bronze Age in Serbia has long been debated, with some scholars having complained that the general archaeological picture has changed very little in recent decades, especially when compared to neighbouring areas (e.g. Tasić and Tasić Reference Tasić, Tasić and Grammenos2003: 98). This situation is particularly noticeable given the shortage of absolute chronological information (e.g. Krstić et al. Reference Krstić, Bankoff, Vukmanović and Winter1986; Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999: 404; Bogdanović Reference Bogdanović1986; Gogâltan Reference Gogâltan1999; Bulatović and Stankovski Reference Bulatović and Stankovski2012), until the recent publication of some 14C dates for the site of Bubanj (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017).

Likewise in present Croatia and Albania there is an on-going debate concerning the chronological position of the Early Bronze Age, especially as concerns the extensive interaction networks that connect the western Balkans to the Aegean and southern Italy (i.e. the Cetina phenomenon) and the cultural groups that spread in the entire Macedonian region encompassing different chronological systems (i.e. Armenochori). To avoid confusion in this paper the entire 3rd millennium BC will be referred to as Early Bronze Age.

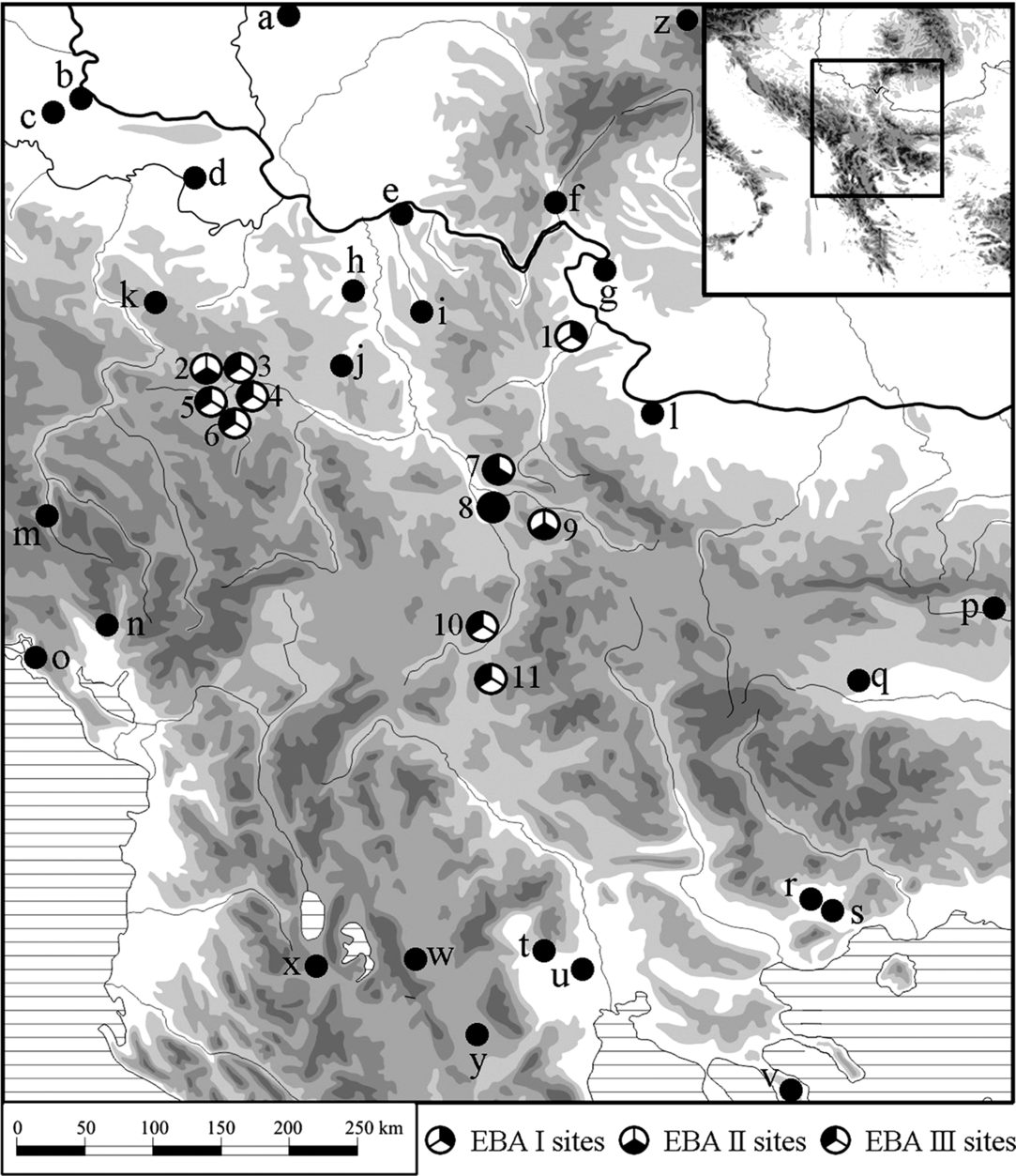

In order to fill this damaging documentary gap, we obtained 25 absolute dates for the end of the 4th and the 3rd millennium cal BC from a series of sites located in modern-day Serbia and North Macedonia (Figure 1). These include a combination of settlements—some of them with stratified deposits—and cemeteries (Table 1), as well as recent and older investigations. As much as possible, dates were obtained on bone samples (including cremations) originating from reliable stratigraphic contexts, demonstrating robust associations with either key ceramic types (e.g. double-handled beakers) or cultural practices (especially cremations), which are at the core of existing typo-cultural arguments for the period and area under consideration. After a brief presentation of the archaeological context of each site, we discuss the implications of our results for our understanding of the chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the central Balkans, and for the wider associated socio-cultural dynamics. In particular, we discuss the absolute chronology for Coţofeni-Kostolac, Belotić-Bela Crkva, Armenochori, and Bubanj Hum III groups, which represent the main cultural units of the central Balkans sequence for the 3rd millennium cal BC.

Figure 1 Sites mentioned in the study: 1. Mokranje, Mokranjske Stene; 2. Jančići, Veliko Polje; 3. Prijevor, Ade; 4. Dučalovići, Ruja; 5. Krstac, Ivkovo Brdo; 6. Lučani, Suva Česma; 7. Hum, Velika Humska Čuka; 8. Novo Selo, Bubanj; 9. Glogovac, Polje; 10. Ranutovac, Meanište; 11. Pelince, Dve Mogili. a. Mokrin, b. Vučedol, c. Vinkovci, d. Gomolava, e. Viminacijum, f. Baile Herculane, g. Ostrovul Corbului, h. Novačka Ćuprija, i. Belovode, j. Ljuljaci, k. Belotić and Bela Crkva, l. Bagačina, m. Odmut, n. Gruda Boljevića, o. Velika Gruda and Mala Gruda, p. Dubene, q. Junacite, r. Sitagroi, s. Dikili Tash, t. Mandalo, u. Archontiko, v. Sykia, w. Armenochori, x. Sovjan, y. Xeropigado, z. Poiana Ampoiului.

Table 1 Absolute dates for the central Balkans EBA groups obtained in this study. The δ13C was obtained from the isotope determination in the AMS system, for collagen on uncremated bones, and on carbonate for cremated ones. This value may be influenced by isotope fractionation and is only used for fractionation correction. Hence, this value is not comparable to the one obtained in a stable isotope IRMS and should not be used for further data interpretation.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA

Stratified Settlements

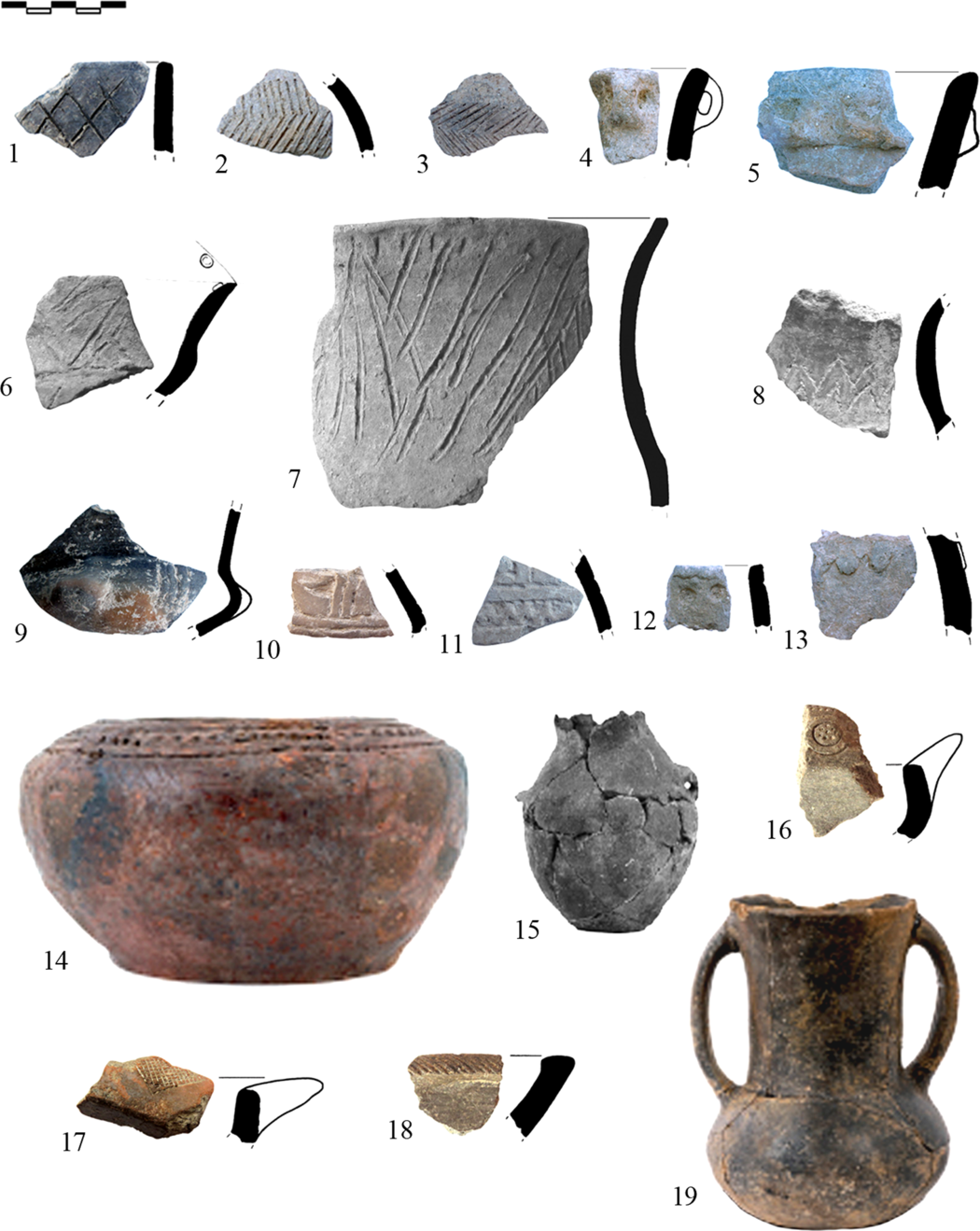

Bubanj is a stratified prehistoric settlement located in the middle course of the Južna Morava River, close to the confluence with the Nišava River, in the Niš plain, southeastern Serbia. The site was excavated on several occasions during the 1930s, 1950s, and lastly between 2008 and 2014 (Orsich-Slavetić Reference Orsich-Slavetić1940; Garašanin M. Reference Garašanin1958a; Bulatović and Milanović Reference Bulatović and Milanović2020). During the last excavation campaigns numerous structures were uncovered, belonging to the Neolithic, Copper and Bronze Ages (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017). One sample (MAMS-31462) was taken from below floor 82A, which possibly belongs to a pre-Coţofeni-Kostolac horizon. The sample was not used in the model presented hereafter, but it is published here for the completeness of the information. The first sample (MAMS-31466) was taken from the remains of the Late Eneolithic dwelling structure 49/93, which according to pottery and stratigraphy (cultural layer IV) belongs to the Coţofeni-Kostolac group (Figure 2/1-3). This group is generally dated to the end of 4th and beginning of the 3rd millennium cal BC (e.g. Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017) and is distributed across the mountainous parts of the Iron Gates hinterland. It is characterized by the occurrence of both Kostolac- and Coţofeni-type ceramics, and by a variety of settlement types (hillforts, plateau and lowland settlements, caves) suggesting an economy based on transhumant herding and landscape control (Kapuran and Bulatović Reference Kapuran and Bulatović2012: 77; Kapuran et al. Reference Kapuran, Bulatović, Milanović, Dietz, Mavridis, Trankosić and Takaoglou2018: 84). Cultural layer IV also yielded sample MAMS-31465, taken from structure 42, a fireplace. Associated pottery is characteristic of the same group (Figure 2/4–5). Sample MAMS-31459 was taken from the remains of dwelling structure 15, belonging to layer IV also belonging to the Coţofeni-Kostolac group. Cultural layer V provided both sample MAMS-31458, taken from the rectangular dwelling structure 83, and sample MAMS-31464, from structure 40 (a concentration of river stones and potsherds). Pottery from both structures has Coţofeni-Kostolacelements and also stylistic and typological traits similar to the Vučedol group (Figure 2/9–13). This is not unusual considering the Vučedol influence in this period in the Morava Valley (Bulatović and Milanović Reference Bulatović and Milanović2020: 129–139). The last sample from Bubanj, MAMS-31461, was taken from structure 91, a pit which was dug from the lower level of layer V deep into layer IV. Associated pottery belongs to the Bubanj-Hum III group (Figure 3/6–7) with some elements of the Bubanj-Hum II group (Figure 3/8).

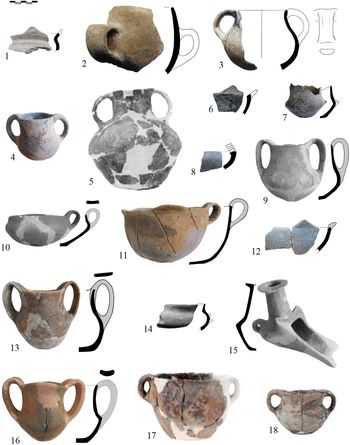

Figure 2 1–3. Bubanj, str. 49/93; 4–5. Bubanj, str. 42; 6–8. Mokranjske Stene; 9–11. Bubanj, structure 83; 12–13. Bubanj, structure 40; 14–15. Jancici, Veliko Polje, grave 2; 16–18. Velika Humska Čuka, structure 6A; 19. Dučalovići, Ruja, mound 12, grave 1.

Figure 3 1–3. Velika Humska Čuka; 4. Pelince, Dve Mogili, pit Б 28; 5. Lučani, Suva Česma, mound 7, central grave; 6–8. Bubanj, structure 91; 9–10. Ranutovac, grave 3; 11–13. Ranutovac, grave 17; 14. Ranutovac, grave 1; 15. Ranutovac, grave 7; 16. Ranutovac, grave 21; 17–18. Prijevor, Ade, mound, central group of vessels.

The site of Mokranjske Stene lies about 8 km south of Negotin in eastern Serbia, not far from the Timok River and the Serbian-Bulgarian border. It encompasses both the hilltop and the foot of the hill along the rocky walls. Excavations undertaken between 2011 and 2013 revealed a small rock-shelter with stratified prehistoric deposits (Bulatović Reference Bulatović, Капуран and Булатовић2015; Bulatović et al. Reference Gori, Gimatzidis, Pieniazek and Mangaloğlu-Votruba2018). The two samples presented here were taken from spits 7 (MAMS-31468) and 12 (MAMS-31469), excavated in trench 2. Spit 7 was formed by a light brown soil and yielded pottery characteristic of the Coţofeni-Kostolac group, while spit 12 corresponded to a yellow soil, containing mixed pottery of Bubanj-Hum I and Coţofeni-Kostolac groups (Figure 2/6–8). Bubanj-Hum I belongs to the Bubanj-Salcuţa-Krivodol cultural complex and dates to the early Eneolithic (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017).

The site of Velika Humska Čuka is, with Bubanj, the eponymous site of the Bubanj-Hum culture (Garašanin M. Reference Garašanin1958a). It is located on the top of a hill at the edge of the Niš plain, about 8 km northeast from Niš in southeastern Serbia. In 2014, remains of settlements dated to Early and Late Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman period were uncovered (Bulatović and Milanović Reference Bulatović and Milanović2015). The first sample (MAMS-31475) was taken from a dwelling structure (structure 6A) in trench I/16S, with numerous potsherds belonging to Bubanj-Hum II group (Figure 2/16–18). The second sample (MAMS-31477) was taken from a pottery scatter in excavation spit 6 attributed to the Bubanj-Hum III group (Figure 3/1-3). The scattered pottery was quite homogeneous from a stylistic and typological point of view. On the other hand, the older layer beneath the pottery scatter belonged to the Coţofeni-Kostolac group, which is dated to between 32nd and 29th century cal BC (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017; this study). For this reason, the possibility that this sample belongs to the older layer and thus to a preceding phase can be excluded.

Ritual Space

The site Pelince Dve Mogili (“Two Mounds”) is situated on a hill overlooking the Pčinja River, in the northern part of North Macedonia, near the border with Serbia. The site was excavated in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Trajkovska Reference Trajkovska1995; Trajkovska Reference Trajkovska2003; Bulatović and Stankovski Reference Bulatović and Stankovski2012). Two areas, interpreted as ritual spaces, were excavated, containing a few dozens shallow circular pits and three pyres covered by earth. The single sample dated here (MAMS-31472) was taken from a pit in quadrant Б28, about 10 m south of the central pyre (Bulatović and Stankovski Reference Bulatović and Stankovski2012: Figure 11). Pottery from the pit (Figure 3/4) belongs to the Bubanj-Hum III—Pelince—Pernik complex, which covers a variety of sites from western Bulgaria, southern Pomoravlje, eastern Serbia and northeastern part of North Macedonia (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2014: 68).

Cemeteries—Inhumations

Two samples were obtained from Polje, in the municipality of Glogovac, southeastern Serbia. The site lies on the left bank of the Crvena Reka and was investigated in 2011–2012 during rescue excavations prior to the construction of a highway (Lazić and Ljuština Reference Lazić, Ljuština and Prodanovic Rankovic2017). Besides the remains of settlements dating to the Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages, one triple grave was also uncovered, from which we obtained two dates (MAMS-31478, MAMS-31479). All skeletons were buried in a crouched position, lying one behind the other. Although the burials did not contain any grave goods, pottery belonging to the Late Coţofeni-Kostolac group, with some Vučedol elements, was found nearby. The Vučedol group initially develops in eastern Slavonia and Srem following the Kostolac group, before undertaking a phase of spatial expansion with both settlements and cemeteries observed across the Carpathian Basin, the western Balkans, and beyond Eastern Europe and the Adriatic.

The site of Veliko Polje is located on the northern slope of the Kablar Mountain in the Jančići village near Čačak, western Serbia. Several funerary mounds are distributed over an elongated ridge, and one of them was excavated in 1979 (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 58–60). The mound, 13 m in diameter, consists of an inner sod-and-earth mound (diam.: 6m), with an outer layer of stones. The central mound contained a stone cist, with a skeleton in crouched position (grave 2) from which sample MAMS-31474 was taken. A small vessel was found in association with the skeleton (Figure 2/15), and another one close to the cist (Figure 2/14). The second presents characteristic Vučedol decoration.

The site of Ruja lies near the village of Dučalovići, western Serbia. This cemetery includes 23 mounds. Five of them, in a better state of preservation, were excavated between 1978 and 1979 (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2002). Mound 12 measures about 10 m in diameter and is 1.2 m high and is made of earth. It contained two graves, including a central stone cist (grave 1), with a skeleton in crouched position, from which sample MAMS-31473 was taken. This grave was associated with a two-handled beaker (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 51–57; Figure 2/19) belonging from a typological point of view to the Belotić-Bela Crkva group. Centred upon western Serbia, this Early Bronze Age group is so far only defined through material culture found in cemeteries of clustered barrows. As most of the Belotić-Bela Crkva pottery is undecorated, existing typologies are based on morphological criteria only and point to links with other contemporary groups in the region, especially the Vinkovci-Somogyvár group.

Cemeteries—Cremations

Ivkovo Brdo is situated on the Krstac Mountain, western Serbia. The site consists of several mounds, five of which were excavated (Nikitović Reference Nikitović2003). The sample reported here (RICH–24515) was taken from mound 1, which measures 10 to 15 m in diameter and is composed by earth and stone slabs. A central stone cist contained the remains of a cremated individual together with one stone triangular arrowhead (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 95–103). Several potsherds were recovered within the body of the mound, but none of them presenting any diagnostic feature. Nevertheless, this context was selected because of its architectural characteristics and the use of cremation.

The site of Suva Česma in Lučani is located on the western slope of Ruja Mountain, western Serbia. Eight mounds were recorded during a survey in the early 1970s, but only mound 7 survived and was recently excavated (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 110–115). Its earthen cover was irregular in shape, and measured ca. 12–15 m in diameter. In the northwestern part of the mound, a circular construction made of stones contained cremated human bones (RICH–24503), a handstone, and some potsherds belonging to four vessels (Figure 3/5) attributed to the Belotić-Bela Crkva group.

The site of Meanište in Ranutovac was excavated in 2012 prior to the construction of a highway. It is located about 5 km northeast from Vranje, in southeastern Serbia (Bulatović, Bizjak and Vitezović Reference Bulatović, Bizjak, Vitezović, Perić and Bulatović2016). The site lies on a slight slope about 600 m from the modern riverbed of the Južna Morava. Together with an Early Iron Age settlement, an Early Bronze Age cemetery was uncovered. The cemetery comprised 21 graves distributed over three separated areas. The graves consisted of circular shallow pits around 0,5 m in diameter, surrounded and covered by stones. Remains of cremated human bones were discovered lying at the bottom of the pits, associated with various vessels, mostly cups. Six samples from different graves were sent for analysis (RICH–24516, RICH–24542, RICH–24543, RICH–24513, RICH–24544, RICH–24514). Pottery grave goods (Figure 3/9–16) belong to the Armenochori group, which is distributed in northwestern Greece, southeastern Albania and southwestern North Macedonia. At present Ranutovac-Meanište marks the northernmost extension of this group.

The cemetery of Ade in Prijevor near Čačak, in western Serbia, is located on the river terrace close to the confluence of the Kamenica and Zapadna Morava rivers (Stojić and Nikitović Reference Stojić and Nikitović1996). The mound consisted of an earthen cover surrounded by a circular ring of river pebbles, and comprised four distinct features, indicating its long-lasting use as a burial place: the primary grave 1 (which dates to the Early Bronze Age), grave 2 (which dates to the Late Bronze Age), a group of vessels placed in the centre of the mound, and a pyre. Grave 1, for which we obtained a radiocarbon determination, is located in the western part of the mound, and consists of a shallow pit about 1 m in diameter filled with cremated human bones (RICH–24502), charcoal and two river stones (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 136–139). Grave 1 did not include any grave good. However, on the basis of typological characteristics, the central group of vessels can be attributed to Bubanj-Hum III or succeeding Bubanj-Hum IV−Ljuljaci groups (Figure 3/17–18).

METHODS

Radiocarbon samples were processed by two distinct laboratories. Bone samples were submitted for counting to MAMS, the AMS facility at the Curt-Engelhorn-Centre for Archaeometry, Mannheim, and were treated following the standard protocol in operation there (Kromer et al. Reference Kromer, Lindauer, Synal and Wacker2013). Cremated human remains were sent to the KIK-IRPA AMS laboratory, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels (Boudin et al. Reference Boudin, Van Strydonck, van den Brande, Synal and Wacker2015). They were pretreated following Van Strydonck et al. (Reference Van Strydonck, Boudin and De Mulder2009). Hereafter CO2 of the cremated bone was released by adding phosphoric acid and graphitization, following Van Strydonck and van der Borg (Reference Van Strydonck and van der Borg1990–1991). As dates on cremated bone actually correspond to the atmospheric 14C during the cremation process, a possible offset between this date and the death of the sampled individual cannot be ruled out because of, for instance, use of very old wood or fossil fuel in the pyre. However, for prehistoric Europe, such offset is generally considered to be minimal and comparable to the decadal inbuilt age of the adult human skeletal (Snoeck et al. Reference Snoeck, Brock and Schulting2014). The δ13C value (see Table 1) was obtained from the isotope determination in the AMS system. This value may be influenced by isotope fractionation and is only used for fractionation correction. Hence, this value is not comparable to the one obtained in a stable isotope IRMS and should not be used for further data interpretation.

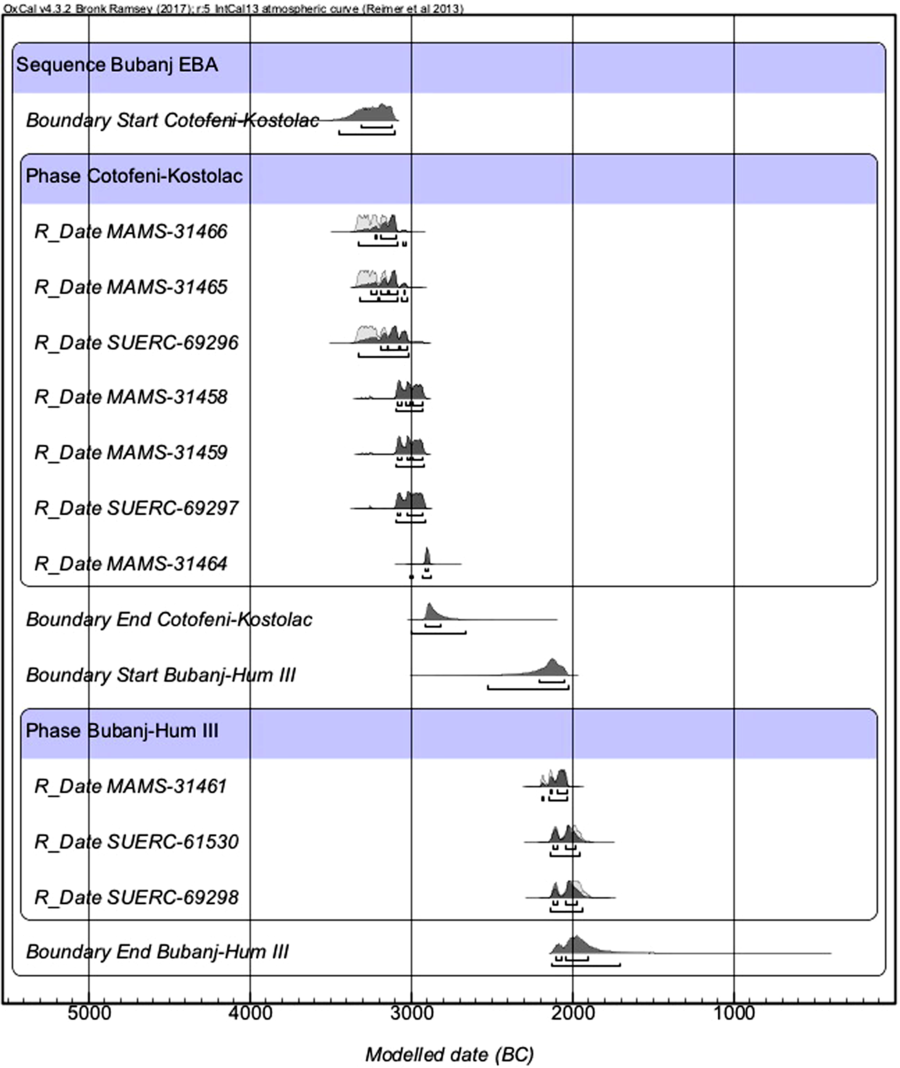

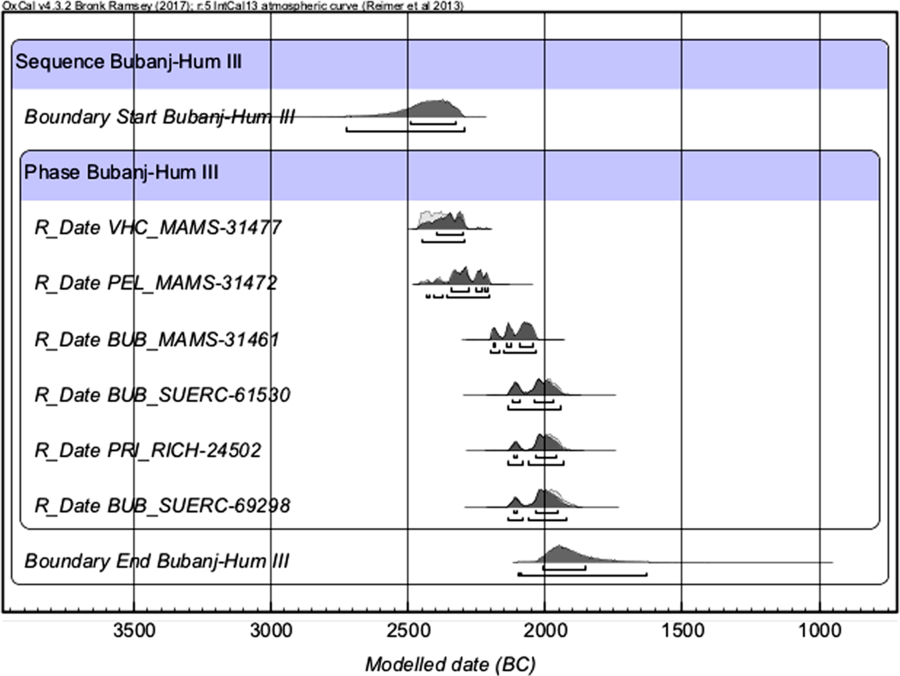

All dates were calibrated using OxCal 4.3 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). In the case of Bubanj, a Bayesian model was built (Figure 5) by combining the radiocarbon dates with the stratigraphic information, the latter providing the necessary prior beliefs (e.g. Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Bronk Ramsey, van der Plicht and Whittle2007). Given the complexity and relative uncertainties of the stratigraphy of the site, our model distinguishes two successive phases corresponding, on the one hand, to layer IV and V/lower horizon (which yielded pottery attributed to the Late Eneolithic Coţofeni-Kostolac group), and, on the other hand, layer V / upper horizon (with pottery belonging to the EBA Bubanj-Hum III group). When multiple dates were available for the same site (e.g. Mokranjske Stene, Ranutovac), a simple Bayesian model was built as a single bounded sequence, thus providing quantitative estimates for the start and end of the modeled phases. The same approach was adopted for collating and analysing dates belonging to the same cultural group. Despite this, it must be noted that, in several instances, the resulting models remain relatively imprecise, either due to limited information, or to the shape of the calibration curve of the 3rd millennium cal BC, characterized by a succession of plateaus and peaks.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Early Bronze Age 1

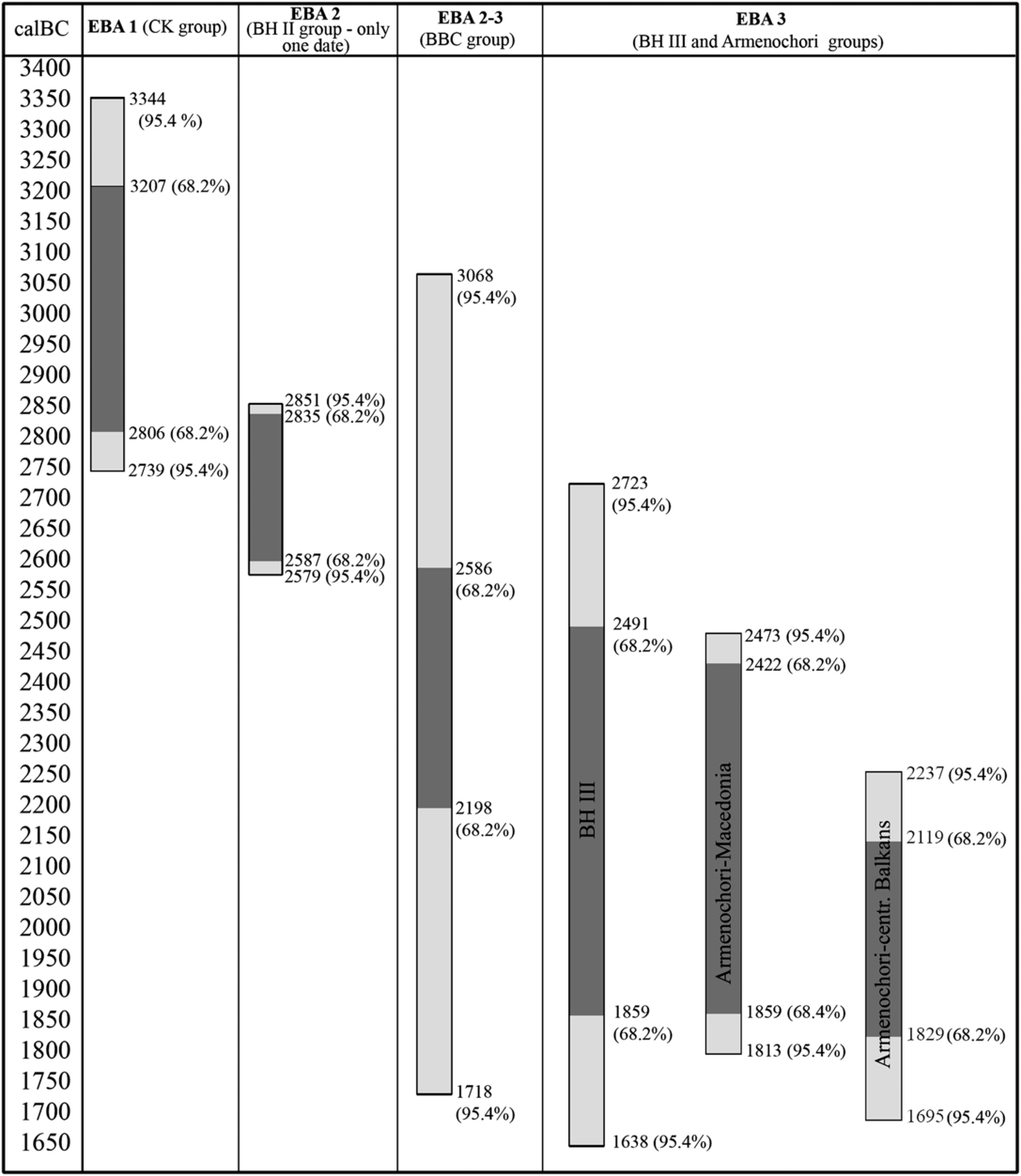

Of the 25 dates presented in this paper, ten belong to the Late Eneolithic, according to Serbian chronology, or Early Bronze Age 1 (hereafter EBA 1) following the chronology used in Greece and Bulgaria. Six originate from Bubanj, two from Mokranjske stene, and two from Polje in Glogovac (Table 1). According to stylistic and typological characteristics of ceramics and other finds, the EBA 1 levels of these sites were attributed to the Coţofeni-Kostolac group as defined by Jovanović (Reference Jovanović1976), followed by Tasić (Reference Tasić1979), Nikolić (Reference Nikolić1997) and Kapuran and Bulatović (Reference Kapuran and Bulatović2012). A total of 29 dates from Serbia and Romania are included in the EBA 1 model, comprising the following sites: Bubanj (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017), Mokrajnske Stene, Jančići, Glogovac, Vučedol (Benkö et al. Reference Benkö, Horvath, Horvatinčić and Obelić1989), Pivnica (Durman and Obelić Reference Durman and Obelić1989, Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher1993), Gomolava (Durman and Obelić Reference Durman and Obelić1989, Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher1993), Belovode (Borić Reference Borić, Keinlin and Roberts2009), Ostrovul Corbului (Breunig Reference Breunig1987), Băile Herculane (Breunig Reference Breunig1987), Poiana Ampoiului (Ciugudean Reference Ciugudean1996). The beginning of this cultural group falls between 3207 and 3105 cal BC (68.2% probability), or 3344 and 3097 cal BC (95.4% probability), while its end dates to between 2864 and 2806 cal BC (68.2% probability), or 2878–2739 cal BC (95.4% probability). The duration of this group is estimated at 255–402 years (68.2% probability), or 234–587 years (95.4% probability) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Coţofeni-Kostolac group, EBA 1 (BEL = Belovode, BHE = Baile Herculane, BUB = Bubanj, GLO = Glogovac, GOM = Gomolava, MOK = Mokranjske stene, PIV = Pivnica, OCO = Ostrovul Corbului, POI = Poiana Ampoiului, VUC = Vučedol.)

The Coţofeni-Kostolac group at Bubanj is concurrent with the presence of Kostolac and Coţofeni groups across modern-day Serbia. At Bubanj the model for the Coţofeni-Kostolac group was based on seven dates, of which two (SUERC-69296 and SUERC-69297) have been previously published (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017). The Coţofeni-Kostolac group starts between 3273 and 3106 cal BC (68.2% probability), or 3344 and 3100 cal BC (95.4% probability) and ends between 2856 and 2749 cal BC (68.2% probability), or 2866 and 2684 cal BC (95.4% probability). It thus spans a duration of 265–461 years (68.2% probability) or 248–628 years (95.4% probability) (Figure 5, top). In respect to the previously published results (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017), the chronological definition of the Coţofeni-Kostolac group at Bubanj improved thanks to a better data set and thus more reliable Bayesian model. The dates in this paper further improve the chronological framework of the EBA 1 in the central Balkans and challenge the well-established assumption that the Coţofeni-Kostolac group would be younger than both Kostolac and Coţofeni groups. The younger dates from Coţofeni-Kostolac layers at Bubanj and Glogovac, and the date for the following EBA 2 phase at Velika Humska Čuka combined with stylistic and typological analysis of ceramics suggest that there is no significant chronological hiatus between the EBA 1 Coţofeni-Kostolac and the following EBA 2 Bubanj-Hum II groups.

Figure 5 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Coţofeni-Kostolac (EBA 1) and Bubanj-Hum III (EBA 3) groups from Bubanj.

Early Bronze Age 2

Two samples date to Early Bronze Age 2 (hereafter EBA 2; or Late Eneolithic using the existing Serbian system), the first one originates from Jančići in western Serbia (MAMS-31474), and it comes from an inhumation grave under a tumulus, in which an early-classical Vučedol vessel was discovered (Dimitrijević Reference Dimitrijević1979: Figure 4/19–22). The grave in Jančići is dated to a period between 2849 and 2627 cal BC with 68.2% probability, which approximately corresponds to the classical horizon of the Vučedol group (Durman and Obelić Reference Durman and Obelić1989: Table 1). Vessels similar for shape but with slightly different decoration, were recorded near Loznica (Garašanin M. and Garašanin D. Reference Garašanin and Garašanin1962: Figure 12), in a mound attributed to the Belotić-Bela Crkva group. The second sample originates from a possibly residential structure in Velika Humska Čuka (MAMS-31475), in which exclusively Bubanj-Hum II pottery is recorded (Figure 2/16–18). This group has been defined by Garašanin M. (Reference Garašanin1958b) on the basis of stylistic and typological ceramic features of Bubanj and other sites, and stratigraphy at Bubanj. Its origins and its relationship with similar cultural phenomena in the surrounding areas (e.g. horizon IIB in Dubene, and horizons 8–5 of Junacite in central Bulgaria, Bagačina in NW Bulgaria: Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999; Alexandrov Reference Alexandrov, Stefanovich and Angelova2007) are still unclear. In terms of ceramic style and typology, Bubanj Hum II holds some elements of the previous Coţofeni-Kostolac group, however typical Vučedol decorative traits are also present. Besides pottery, contacts between these groups are also suggested by the contemporaneity between the absolute dates for the Vučedol group, and the sole date for the Bubanj-Hum II group, published here. The Vučedol ceramic horizon is distributed over a large part of the Balkans comprising Pannonia and the entire East Adriatic coast, and has been dated to the first half of the 3rd millennium BC, probably from around 2900 to 2600 cal BC (Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher1993: 247; Velušček and Čufar Reference Velušček and Čufar2014: 42–43; Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher2018a: 133). The dating from Velika Humska Čuka (MAMS-31475; 2835–2587 cal BC, 68.2% probability, 2851–2579 cal BC, 95.4 probability) represents the oldest from a Bubanj-Hum II context, since at Dubene a somewhat younger date is recorded (2580–2470 cal BC with 68.2% probability). Data for the horizons 8–5 at Junacite, where pottery with identical decoration as at Velika Humska Čuka is recorded (Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999: 203, 227, Table 9.2, Table 10.2) indicate an even younger dating (2402–2210 cal BC with 68.2% probability). At present EBA 2 remains the most poorly defined horizon of the 3rd millennium cal BC in the area under analysis, however it is now clear that it is contemporaneous with the EBA 2 Bulgarian Dubene group (Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999; Nikolova and Görsdorf Reference Nikolova and Görsdorf2002).

Early Bronze Age 2-3

Most of the dates presented in this study (13 in total) belong to the EBA 2-3 and EBA 3 or the final stage of the Late Eneolithic and beginnings of the Early Bronze Age according to Serbian chronology. The oldest dates come from two samples taken from cist graves under tumulus located in different areas of western Serbia. While the deceased from Krstac was cremated (RICH–24515), the burial from Dučalovići was an inhumation (MAMS-31473) (Dmitrović Reference Dmitrović2016: 50–57, 94–103). Interestingly, the two dates are quite close. Based on the characteristics of pottery from Dučalovići (Figure 2/19), the tumulus can be assigned to the Belotić-Bela Crkva group, which was defined by M. Garašanin who also underlined the coexistence of both rituals within the group (Garašanin M. Reference Garašanin1973: 253–266). The cremation burial at the tumulus in Lučani (RICH 24503) was assigned to the Belotić-Bela Crkva group on the basis of typological characteristics of the grave goods (Figure 3/5). Although no diagnostic ceramics were recorded in the burial of Krstac, given its chronology, which is comparable to Dučalovići, and the fact that both cremation and inhumation are attested within the Belotić-Bela Crkva group, it can be assumed that the tumulus from Krstac belongs to the same group.

According to the Bayesian model (Figure 6), the start of Belotić-Bela Crkva falls between 3068 and 2311 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2586–2366 cal BC (68.2% probability). The end dates to between 2461 and 1718 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2431–2198 cal BC (68.2% probability). Based on these dates, the group would last 0–1197 years (95.4% probability), or 0–368 years (68.2% probability). Large temporal brackets for all measures at 95.4% probability are related to the low number of dates included in the model, and the absence of true boundaries.

Figure 6 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Belotić-Bela Crkva group, EBA 2-3 (DUC = Dučalovići, LUC = Lučani).

The chronology of Belotić-Bela Crkva and its comparison to other groups has been always rather problematic (Maran Reference Maran1998: 322). Even if uncertainty remains, it is possible to propose that Belotić-Bela Crkva is contemporaneous with the neighbouring Vinkovci-Somogyvár group (Kalafatić Reference Kalafatić2006: Table A; Kulcsár Reference Kulcsár, Anders, Kulksár, Kalla, Kiss and Szabó2013: Table 1), somewhat younger than Makó-Kosihy Čaka (Kulcsár Reference Kulcsár2009: 15), and older than the Moriš group (Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999: 405). The existence of an EBA 2-3 chronological horizon embodied by the Belotić-Bela Crkva group, is supported by the Loznica findings (Garašanin M and Garašanin D Reference Garašanin and Garašanin1962: Figure 12), in which Belotić-Bela Crkva ceramics were found together with ceramics with elements of classical Vučedol group. Belotić-Bela Crkva is also connected to the Adriatic Cetina group. The presence of Cetina material culture in the interior of the Balkans is well-attested; for instance, pottery finds in several sites in Bosnia and Herzegovina and western Serbia (Govedarica Reference Govedarica2006; see below), and by numerous vessels with distinctive traits from both Cetina and Belotić-Bela Crkva (e.g. Vrtanjak; Govedarica Reference Govedarica2006: 36).

The Cetina group is identified by its characteristic decorated pottery and burials under tumuli, which spread in the central Balkans (Govedarica Reference Govedarica2006; Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher2018a) and over Dalmatia down to Peloponnese and further across the Central Mediterranean in the second half of the 3rd millennium cal BC. Given the paucity of stratified and closed Cetina contexts and of 14C dating, to propose a reliable chronology for this widespread and long-lasting phenomenon represents a challenging enterprise (see recently Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher2018a: 135–140). It is clear that that the Ljubljana-Cetina phenomenon comprises several phases covering much of the 3rd millennium cal BC. The earliest one (Ljubljana-Adriatic) seems to belong to the second quarter of the third millennium BC, while the last two (here referred to as Cetina 1 and Cetina 2) are likely to encompass both the second half of the 3rd and the first century of the 2nd millennium cal BC (Gori Reference Gori2020). On the basis of absolute dating combined with ceramic typology from different sites in the Mediterranean, Jung and Weninger (Reference Jung, Weninger, Meller, Arz, Jung and Risch2015) suggest a terminus post quem for their classic Cetina (corresponding to Cetina 2) around 2250 cal BC. It can be thus suggested that Belotić-Bela Crkva is contemporaneous with the phase Cetina 1, while Cetina 2 would be contemporaneous with Bubanj-Hum III and the second horizon of Armenochori (see here below). The last is also suggested by the presence of few decorated potsherds with Cetina 2 features in Sovjan level 7 (Gori Reference Gori2015a). However, it has to be noted that tankards recalling Belotić-Bela Crkva examples were recovered in both Sovjan levels 8 and 7 (Gori Reference Gori2015a: 87–90). This is the first attempt of correlating absolute chronology of the central and western Balkans, however a larger number of radiocarbon dates from reliable contexts is required to improve this correlation and better understand cultural connections between these areas.

The correlation between central Balkan EBA 2-3 and northern Greece also presents some difficulties, as an intermediate period between EBA 2 and EBA 3 was only recognized in the southern Greek Mainland and in the Cyclades (Arvaniti and Maniatis Reference Arvaniti and Maniatis2018: 765–766, Table 2). On the contrary, the northern Greek sequence is divided in three phases, with corresponding Bayesian analysis (Arvaniti and Maniatis Reference Arvaniti and Maniatis2018: Fig. 6). This further confirms the need for a larger number of radiocarbon dates from reliable contexts and for cross-regional analysis.

Early Bronze Age 3

Four dates belong to the Bubanj-Hum III group, originally defined by M. Garašanin in the 1950s (Garašanin M. Reference Garašanin1957: 205–207). The samples here analysed come from Velika Humska Čuka, Bubanj, Prijevor and Pelince. The Bayesian modeling of the dates available for the Bubanj-Hum III group, which comprise the aforementioned four dates and the further two from Bubanj already published (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017) yielded the following results: Bubanj-Hum III group would start between 2723–2296 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2491–2296 cal BC (68.2% probability), while its end would fall into 2085–1638 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2006–1859 cal BC (68.2% probability). The duration of the Bubanj-Hum III group would be of 275–983 years (95.4% probability), or 365–633 years (68.2% probability) (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Bubanj-Hum III group, EBA 3 (BUB = Bubanj, PEL = Pelince, PRI = Prijevor, VHC = Velika Humska Čuka).

The earliest available date of this group comes from Velika Humska Čuka (MAMS-31477). This date is about two to three centuries older than the ones previously published for this group (Bulatović and Vander Linden Reference Bulatović and Vander Linden2017), and the other dates obtained with this study. Although we cannot totally exclude the risk of residuality for this particular sample, it is noticeable that this date, which originates from an archaeological context yielding stylistically and typologically homogeneous pottery, presents a large overlap with the second older date. The latter originates from the ritual area in Pelince (MAMS-31472), which yielded numerous ceramic finds the stylistic and typological characteristics of which correspond to examples from southwestern Bulgaria and southeastern Serbia. By comparison, the other two dates (site of Bubanj, MAMS-31461; Prijevor, RICH–24502) are a little bit younger, pointing to the very end of the 3rd millennium cal BC, or the beginning of the 2nd millennium cal BC. The name Bubanj-Hum III-Pernik-Pelince was suggested for this wider cultural phenomenon by one of the authors (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2014: 68, Map 2).

Although these results should be taken with caution given the low number of available samples, when singling out the dates available for the Bubanj-Hum III group on the eponymous site of Bubanj, it seems that here this phase started with a delay of two to three centuries (Figure 5, bottom). The internal Bayesian model for Bubanj indicates that this phase started there between 2473–2030 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2196–2048 cal BC (68.2% probability). The end of Bubanj-Hum III group falls at Bubanj between 2129–1781 cal BC (95.4% probability) and 2106–1916 cal BC (68.2% probability). Its duration is estimated at 0–604 years (95.4% probability), or 0–237 years (68.2 % probability). The uncertainty towards the duration of the BH III group at 95.4% probability is related to the limited number of dates and the shape of the calibration curve for the 3rd millennium cal BC.

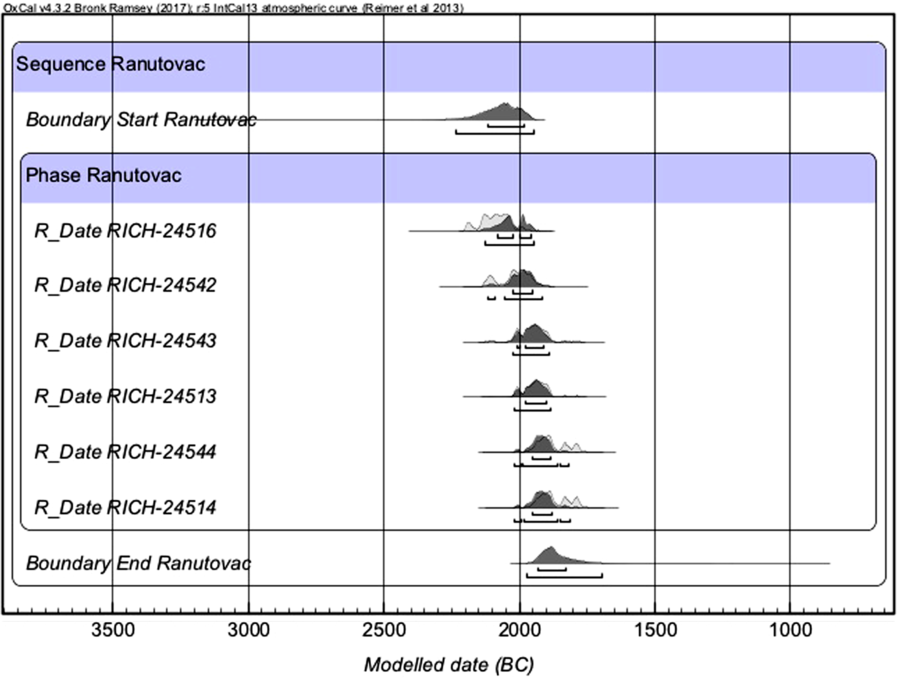

The last set of dates comes from Meanište in Ranutovac. According to typological characteristics of ceramics (Figure 3/9–14, 16; compare Bulatović, Bizjak and Vitezović Reference Bulatović, Bizjak, Vitezović, Perić and Bulatović2016) and the presence of miniature oven models with long chimneys (Figure 3/15) (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2013), referred to also as smoking pots (Gori Reference Gori, Suchowska-Ducke, Scott Reiter and Vandkilde2015b: 45), this cemetery can be ascribed to the Armenochori group, of which Ranutovac represents its northernmost manifestation. Considering the model based exclusively on Ranutovac (Figure 10), the time in which the cemetery was in use is comprised to between 2237–1947 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2119–1984 BC (68.2%) for its start, and to between 1971–1695 cal BC (95.4%), or 1933–1829 cal BC (68.2% for its end. In that case, the cemetery would have been in use for 0–470 years (95.4%), or 74–294 years (68.2%).

It is noteworthy that there is no spatial coherence to these results, as for instance samples lying both at the beginning (RICH–24516) or the end of the sequence (RICH–24514) come from the same sector. The same conclusion applies to all other samples. The cemetery of Ranutovac was partially damaged by agricultural works, so it remains unknown whether the graves were originally covered by one or several burial mounds. With the exception of Ranutovac, cemeteries that exclusively contained cremations have not been recorded in the central Balkans for the Early Bronze Age (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2014: 66–67). A parallel can be established with Kriaritsi, a cemetery located in the Chalkidiki Peninsula (Asouhidou Reference Asouhidou2011). Both cemeteries are related by the exclusive use of cremation, funerary architecture and spatial organization of the graves. It must be noted however that pottery from Kriaritsi presents typological links with Thessaly and southern Greece (Wiencke Reference Wiencke2000) rather than with Macedonia and central Balkans. The joint use of cremation and inhumation is attested at Xeropigado (Ziota Reference Cr1998), Agios Mamas (Pappa Reference Pappa2010), and Nea Skioni (Tsigarida and Mantazi Reference Tsigarida and Mantazi2004) in northern Greece, and Steno on Lefkada (Dörpfeld Reference Dörpfeld1927: 220–227). In these cases, cremation is always a minor form of body treatment. Structures from the last two sites present close similarities with the architecture of Kriaritsi (Forsén Reference Forsén and Cline2012: 55) and Ranutovac. Steno is a key site for Aegean–Balkan relationships both for the presence of diagnostic Balkan material culture (Kilian-Dirlmeier Reference Kilian-Dirlmeier2005) and because it is one of the few known examples of EH II-III tumuli in Greece (Müller Celka Reference Müller Celka2012: 415–416), an architectural type often assumed to originate from the Balkans. The combined use of cremation and inhumation is also attested in the entire Dalmatian region. Cetina cemeteries, dated to the second half of the 3rd millennium cal BC, comprise tumuli, often clustered, under which different types of burials are placed, including single or multiple inhumations (mostly but not exclusively in stone cists) as well as cremations possibly placed in urns (Marović Reference Marović1991).

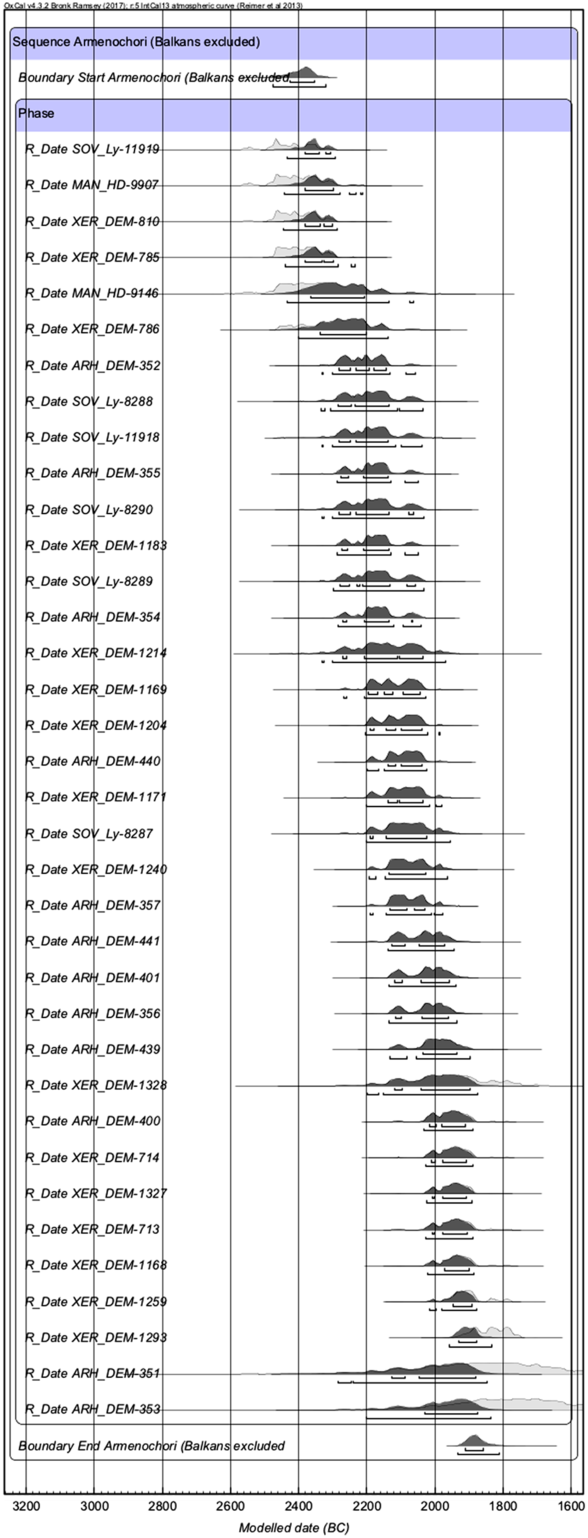

The site of Ranutovac is also important because of the typology of the ceramic grave goods, typical of the Armenochori group. In order to observe eventual spatial variation in the distribution patterns of Armenochori sites, two Bayesian models were produced: a comprehensive one for the group (Figure 8), and another one excluding Ranutovac (Figure 9). The global model (Figure 8) comprises 42 dates from Archontiko (Papaefthimiou Papanthimou and Pilali Papasteriou Reference Papaefthymiou Papanthimou and Pilali Papasteriou1997), Mandalo (Maniatis and Kromer Reference Maniatis and Kromer1990), Ranutovac (present study), Sovjan (Lera and Touchais Reference Lera, Touchais, Cabanes and Lamboley2004; Gori Reference Gori, Suchowska-Ducke, Scott Reiter and Vandkilde2015b), and Xeropigado Koiladhas (Maniatis and Ziota Reference Маniatis and Ziota2011). It shows that its start falls into 2467–2316 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2421–2351 cal BC (68.2% probability), and its end by 1916–1784 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 1901–1851 cal BC (68.2% probability), while the duration was estimated at 425–638 years (95.4% probability), or 463–562 years (68.2% probability). Without surprise given the amount of overlap between them both, the second model (i.e. excluding Ranutovac; Figure 9), provides strikingly similar results, with a start corresponding to 2473–2318 cal BC (95.4% probability), or 2422–2354 cal BC (68.2% probability), and an end to 1932–1813 cal BC (95.4% probability) or 1911–1859 cal BC (68.2% probability), for a duration of 420–632 years (95.4% probability), or 460–557 years (68.2% probability).

Figure 8 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Armenochori group, EBA 3, including Ranutovac (ARH = Archontiko, MAN = Mandalo, RAN = Ranutovac, SOV = Sovjan, XER = Xeropigado).

Figure 9 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for the Armenochori group in Greece, EBA 3, excluding Ranutovac (ARH = Archontiko, MAN = Mandalo, SOV = Sovjan, XER = Xeropigado).

Using the “difference” function in OxCal to compare the start dates for this second model and the Ranutovac one (corresponding to the label Armenochori—central Balkans on Figure 10), it appears that the Ranutovac sequence begins with a delay of 244–400 years (68.2% probability) or 121–429 years (95.4% probability).

Figure 10 Bayesian modeling of 14C dates for Ranutovac, EBA 3.

Although based on limited evidence, these results thus suggest that the Armenochori cultural group can be tentatively divided into two partially overlapping phases, and that it is possible to observe an expansion of Armenochori features from central Macedonian region towards the north (Hammond Reference Hammond1972: 240; Bulatović Reference Bulatović2014: 68) along the upper stream of the South Morava River (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2014: Map 2), the west (Gori Reference Gori2020) and the south, towards the Chalkidiki Peninsula in its second phase in the last quarter of the 3rd millennium cal BC. The existence of two phases was already hinted at by typological and, in very few cases, stratigraphic evidences (e.g. Sovjan, Albania, Gori Reference Gori2015a); however, it was never demonstrated with absolute chronological data. The results presented here, therefore, are particularly encouraging. Furthermore, ceramic assemblages suggest some relationship between both Cetina and Armenochori groups. Two-handled beakers from Cetina contexts show a combination of distinctive Cetina decorative traits with Armenochori typological features (e.g. double-handled vessels from Jukić; Olujić Reference Olujić2012: Pl. 8; Bajagić; Govedarica Reference Govedarica1989: Pl. XLVI/2; and Shtoj; Govedarica Reference Govedarica1989: Pl. XXIX/1). Likewise, several vases found in Armenochori sites present features echoing Cetina and wider Aegean traditions (e.g. the pedestal-footed vessel from grave 2 at Ranutovac; Bulatović et al. Reference Bulatović, Bizjak, Vitezović, Perić and Bulatović2016: Pl. I/5 that compares to Cetina examples from tumulus 2 at Shkrel, Albania Jubani Reference Jubani1995; Maran Reference Maran2007: 15; Gori Reference Gori2020).

The smoking pot/miniature oven model found by Tsountas (Reference Tsountas1908: 274, Figure 198) in the uppermost destruction levels at Sesklo is the southernmost known example of this type of object (Bulatović Reference Bulatović2013; Gori Reference Gori, Suchowska-Ducke, Scott Reiter and Vandkilde2015b), and together with the well-known presence of Cetina pottery in the Peloponnese at e.g. Olympia, Lerna, Andravida Lechaina, Teichos Dymaion (Gori et al. Reference Gori, Gimatzidis, Pieniazek and Mangaloğlu-Votruba2018), and ceramic features of southern origin in central Balkans (Gori Reference Gori2015a, Reference Gori, Suchowska-Ducke, Scott Reiter and Vandkilde2015b, Reference Gori2020) it confirms that central and western Balkans were closely connected to Greece down to the Peloponnese.

The chronology of the eponymous site of Armenochori, excavated in the 1931 by Heurtley (Reference Heurtley1939: 57–59), has always posed problems (Hanschmann and Milojčić Reference Hanschmann and Milojčić1976: 212; Aslanis Reference Aslanis1985: 278; Maran Reference Maran1998: 106–107), as until recently it represented the only site whose ceramics connected the central Balkans to the Greek mainland. Despite new excavations, Armenochori stratigraphic and ceramic sequences remain regrettably unpublished except for a concise report (Chrysostomou Reference Chrysostomou and Lilimpake-Akamate1998). Since several sites yielding Armenochori type ceramics have been excavated and published—including Archontiko (Merousis Reference Merousis, Alram-Stern, Felten and Efstratiou2004), Mandalo (Papaefthymiou Papanthimou and Pilali Papasteriou Reference Papaefthymiou Papanthimou and Pilali Papasteriou1997), Sovjan (Gori Reference Gori2015a), Xeropigado (Ziota Reference Cr1998), and Ranutovac (Bulatović et al. Reference Bulatović, Bizjak, Vitezović, Perić and Bulatović2016)—this new information allows for a better understanding of the typological development of this group, which will require chronological elucidation through further 14C sampling. Even though the definition of the Armenochori cultural group is no longer based on the Armenochori sequence, this name is maintained to avoid possible confusion. Typical ceramics for this group are double-handled beakers, referred to also as kantharoi, and smoking pots/miniature oven models.

Two-handled beakers group together vessels with a variety of morphologies ranging from open, shallow examples to deep, closed forms. Handle shape may also vary substantially. Two-handled beakers are known from an area extending from Transdanubia to continental Greece during a period spanning the 5th to 1st millennium BC. The initial identification of the Armenochori group was based solely on the presence or absence of two-handled beakers, which, together with jars of “unfamiliar forms”, characteristic plastic enhancement of tubular handles, and the near absence of bowls with incurving rims, convinced Heurtley to consider Armenochori separately from other sites discovered in Macedonia (Heurtley Reference Heurtley1939: 85). Two-handled beakers are present also at sites belonging to Bubanj-Hum III, while in the Belotić-Bela Crkva assemblages there are no two-handled beakers that resemble Armenochori, Bubanj-Hum III or Maroš examples, but a variant of this shape with an elongated cylindrical, sometimes funnel shaped neck. Only one two-handled beaker, together with other finds characteristic for the Bubanj-Hum III group (Figure 3/17–18), has been found at Ada in Prijevor (RICH 2450). Absolute dating shows that Ada belongs to a younger horizon with respect to Belotić-Bela Crkva burials. These data further hint at the chronological precedence of Belotić-Bela Crkva in respect to Bubanj-Hum III and Armenochori. Dates from Novačka Ćuprija (Nikolova Reference Nikolova1999: 404: sample codes Beta 2572 and BC 84) where pottery partially matching with the stylistic and typological elements of the Bubanj-Hum III group was found, as well as new dates from Viminacium (Bulatović, Kapuran and Milovanović Reference Bulatović, Kapuran, Milovanović, Kapuran, Bulatović, Filipović and Golubović2019) point to a possible expansion of the Bubanj-Hum III group towards north at the end of the 3rd millennium BC.

CONCLUSIONS

During the 3rd millennium BC, the Balkans were subdivided into a mosaic of overlapping networks with different ranges. For the early part of the 3rd millennium BC, metal objects found in funerary assemblages of the south Adriatic Vučedol group provide the only evidence for long-distance networks connecting the Balkans to the Aegean and even Anatolia (Maran Reference Maran2007). From the mid-3rd millennium BC onwards the Balkans were connected with the Central Mediterranean through supra-regional networks such as the Bell Beaker phenomenon (e.g. presence of Bell Beaker-related wrist-guards in several Dalmatian sites: Heyd Reference Heyd2007; Forenbaher Reference Forenbaher2018a; Gori Reference Gori2020). Further examples of such extensive interaction comprising also the Aegean include the Cetina phenomenon, as well as the large-scale distribution of tankards with an oval body and cylindrical neck (typical of the Belotić-Bela Crkva) and two-handled beakers (the so-called Armenochori kantharoi) in funerary contexts found in an area extending from Transdanubia to continental Greece. At the end of the 3rd millennium BC, there is an apparent increase in connectivity that cross-linked Central Mediterranean and Balkan networks, with emphasis on a north-south axis that crosses the Peninsula. In the central Balkans, a major difficulty in the identification and interpretations of the trajectories of such distant connections is in the lack of a solid chronological framework.

Through a combination of 25 new radiocarbon dates and re-examination of the existing documentation, this paper defines the absolute chronology for groups which were previously only broadly framed into the early 3rd millennium BC (Figure 11). These absolute dates have allowed us to establish with greater clarity the chronological relations between different cultural groups in the central Balkans. Yet, when comparing together the chronologies for material culture, funerary treatment of the body (i.e. inhumation, cremation) funerary architecture, there are no easily discernible patterns.

Figure 11 Chronological table for EBA in the central Balkans (Abbreviations for cultural groups: CK – CotofeniKostolac; BH II – Bubanj-Hum II; BH III – Bubanj-Hum III; BBC – Belotić-Bela Crkva)

Available evidence points to the fundamental role of the funerary sphere as an area for social and cultural negotiations. For instance, the dates obtained in this study for western Serbia confirm that cremation and inhumation were used in conjunction in the Belotić-Bela Crkva group (EBA 2-3 ca. 2700–2100 cal BC), whilst the only inhumation was attested in EBA 1 (c. 3200–2800 cal BC).

We also reported the earliest dates for the Bubanj-Hum III group and for the two-handled beakers phenomenon in the central Balkans. Our dating programme and analysis confirms that the Armenochori and Bubanj-Hum III groups chronologically overlap during a significant part of the 3rd millennium cal BC (e.g. Maran Reference Maran1998: 109–110). Although the Armenochori group is first observed in geographic Macedonia from the third quarter of 3rd millennium cal BC onwards, its influence, under the form of pottery traits, is not attested in the central Balkans until the end of the 3rd millennium cal BC.

Rather than a single area of origins for all traits, we observe a complex mix of traits criss-crossing over a wide area encompassing the Pannonian basin, the central Balkans and the Greek peninsula. Communities living in the Balkans during the end of the 4th and the 3rd millennium cal BC were entangled in a web of exchange and dynamic borrowing different cultural traits, the precise organization of which remains to be further described and explained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, which provided generous financial support to the project “Rewriting Early Bronze Age Chronology in the southwestern Balkans: Evidence from Large-Scale Radiocarbon Dating”. The analyses of the samples were undertaken at the CEZ Archäometrie gGmbH Laboratory in Mannheim, Germany (Dr. Ronny Friedrich), and at the KIK-IRPA, The Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Belgium (Dr. Mathieu Boudin). The authors want to thank the Institute for Pre- and Protohistory of the University of Heidelberg, which hosted the project and provided logistic support and M. Milinković for background of the map (Figure 1). We thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and their many insightful comments and suggestions.