INTRODUCTION

Throughout the past five centuries, cod (Gadus morhua) on the Grand Banks in the Northwest Atlantic off Newfoundland sustained the largest single fishery on the planet. When this cod stock collapsed in 1991, it was an indictment of human environmental management practices and a salutary warning regarding the human impact on marine life. The rise of the fishery in the early decades of the sixteenth century was similarly of momentous consequence for peoples on both sides of the North Atlantic. We propose the concept of the “Fish Revolution” as a means of representing both the known and as yet only dimly perceived or hypothetical societal impacts wrought by the opening of this fishery. The Fish Revolution dramatically increased fish supplies, primarily cod (Gadus morhua), to the European market shortly after AD 1500, a period also marked by great societal and environmental upheaval (e.g., Parker, Reference Parker2013; Campbell, Reference Campbell2016).

In this article, we argue that the Fish Revolution must be understood in the context of climate change and market globalisation. We present preliminary estimates of supplies from the main catch areas of North Norway, Iceland, and Newfoundland/Grand Banks; map changing fishing effort; and discuss drivers and effects of a globalising seafood market. We identify basic ecological and anthropogenic parameters of the Fish Revolution and propose ways forward to understand the Fish Revolution as it related to climate-driven changes to the natural system and globalisation of the human system. The Fish Revolution should be recognised as a major event in global human history, and we call for collaborative multi- and interdisciplinary research to understand (1) the natural abundance and dynamics of the resource, (2) the shock to and long-term impact on the dynamics of the European food system, and (3) the consequences for human landscapes and migration patterns on both sides of the North Atlantic.

THE NORTH ATLANTIC FISH REVOLUTION

In the late Middle Ages (ca. AD 1300–1500), fish was a high-priced, limited resource. Returns on fishing efforts in Europe were so lucrative that historians have identified the period as the second phase of commercialisation of the fisheries (Kowaleski, Reference Kowaleski2003; Gardiner, Reference Gardiner, Barrett and Orton2016) (following the first breakthrough of intensified sea fishing in the eleventh century; Barrett, Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004). The most important species were herring (Clupea harengus) and cod (Barrett and Orton, Reference Barrett and Orton2016). Fresh marine fish was only used for local consumption while markets farther than 30–50 km from the coast depended on dried and salted goods (Hoffman, Reference Hoffmann2005; Amorim, Reference Amorim, David and Starkey2009).

In the latter half of the fifteenth century, fishers and explorers from many countries were pushing into the North Atlantic, but it is Giovanni Caboto (a Venetian navigator, also known as John Cabot) who is generally credited with the European discovery of the Grand Banks. In 1497, he returned to Bristol from a voyage commissioned by Henry VII of England in a vain search for a westerly seaway to China. He told of waters so “full of fish that [they] can be taken not only with nets but with fishing-baskets” (Lawrence and Young, Reference Lawrence, Young, Cape and Smith1931, p. 274; Jones and Condon, Reference Jones and Condon2016). Within a few years, fishers, primarily from the Iberian Peninsula, had journeyed to the waters of which Cabot spoke. Spanish and Portuguese fishers benefitted from easy access to domestic salt, an essential substance for long-distance fisheries. They soon found that the climate was ideal for drying the cod and producing a staple food that would keep for years. The Grand Banks fishery, thus exploited, offered abundant, high-quality, low-priced catches to the European market. This signalled the third and most dramatic phase in the development of North Atlantic fisheries, the Fish Revolution.

In order to assess the importance of this discovery, we present quantitative estimates of the long-term trends in the European fish market. In his overview of early modern (ca. 1500–1750) fisheries, A.R. Michell (Reference Michell, Rich and Wilson1977, p.134) observed that “one reason why the definitive history of European fishing has yet to be written is that quantitative records concerning fishing pre-1750 are few.” A recent survey of European fisheries refrained from making quantitative estimates (Starkey et al., Reference Starkey, Thor and Heidbrink2009). Nevertheless, historians and fisheries scientists have identified and published a significant number of quantitative records in the last 40 yr (reviewed by Poulsen Reference Poulsen, Máñez and Poulsen2016a). Much of this recent research is, however, confined to particular national contexts. We have assembled the evidence for the major exporters—Iceland, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands—of herring and cod for the continental European market, as well as estimates of total production of Newfoundland cod. All figures have been converted from medieval weights to modern metric tonne live weight fish (including heads and guts).

There are important limitations to the picture presented. First, we have refrained from assessing the British market as it was predominantly served by the domestic fishing industry and figures are hence mostly for total landings (local consumption + marketed volume) and therefore not compatible with those for the Continent (marketed values only). The English East Anglian fishery was much reduced by the fifteenth century because of Dutch competition (Childs, Reference Childs2000). The English cod fishery off Iceland was substantial and is estimated to have peaked at about 10,000 metric tonnes by the 1520s. Thirty years later, the fishery was much reduced, but it recovered somewhat by the end of the century and still exceeded English Newfoundland catches until the 1630s (Jones, Reference Jones and Starkey2000). Second, we lack information about some exporters. There was a British and Irish export of herring and cod to the Continent, though we presently estimate that the volumes would have been insignificant for the broad-brush picture we are painting. French fisheries in the North and Celtic Seas would have been significant for the domestic market, and there was a sizable but unknown export of hake (Merluccius merluccius) and cod to Mediterranean countries. Third, we have not considered the southern European market where hake, tuna (Thunnini), and smaller pelagic species dominated.

Figure 1 documents the dramatic increase of fish supplies for the sixteenth-century continental European market. This rise was exclusively because of cod. Around AD 1500, the ratio of herring to cod volumes was about 5:1; by 1600, it was 1:4. Although herring supplies were relatively stagnant, the cod market boomed. In the medieval period, cod was primarily produced as dried fish—so-called stockfish—by Norwegian and Icelandic fishers. Around AD 1400, total Norwegian cod exports were about 6250 metric tonnes, while we estimate Icelandic supplies to have been about 2000–3000 tonnes. By 1550, Norwegian and Icelandic exports had risen to about 15,000 tonnes (Jónsson, Reference Jónsson1994; Nedkvitne, Reference Nedkvitne2014; Nielssen et al., Reference Nielssen, Bjerck, Hutchison, Kolle and Larsen2014), but Newfoundland catches provided the true step change. By 1580, Newfoundland output is estimated to have reached about 200,000 tonnes of cod (Pope, Reference Pope2004a). This was a 15-fold increase in cod supplies, and it tripled overall supplies of fish (herring and cod) protein to the European market. Average annual consumption of imported fish per capita rose from the very low figure of 0.75 kg in 1500 to 3.2 kg in 1650, employing the demographic data of Maddison (Reference Maddison2008).

Figure 1. Old and New World market supplies of cod and herring for the European continent, in metric tonnes. Based on published studies for the exports from Iceland (Jónsson, Reference Jónsson1994), Norway (Nedkvitne, Reference Nedkvitne2014; Nielssen, Reference Nielssen, Bjerck, Hutchison, Kolle and Larsen2014), Denmark (Holm, Reference Holm, Barrett and Orton2016), the Netherlands (Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2008), and Newfoundland landings (Pope, Reference Pope, Starkey and Candow2006). The figures prior to 1600 are best estimates. For the Grand Banks, the 1550 assessment is based on the number of ships active in the fishery. For Norway, the known export in 1577 has been used as a proxy for 1550. For Iceland, we have used the known exports in 1624 as a proxy for 1600, 1655 for 1650, 1733 for 1700, 1753 for 1750, and 1796 for 1800; Icelandic exports in 1300, 1400, and 1550 are calculated as a ratio of Norwegian exports in 1600. The figure for 1500 is an estimate.

The Fish Revolution begs simple but challenging questions. An immediate question may be: Why would European fishers want to cross the North Atlantic to fish? This was a dangerous journey. An abundance of French notarial records attests to the diverse range of hazards such as storms and pirates faced by mariners. Based on sixteenth-century records, we estimate that an average of 5% of vessels in the French fleet were lost in the crossing because of wreckage, capture, and so forth (Archives départementales de Seine Maritime, Rouen, 2E-70). Portuguese inventories document hundreds of ships captured by pirates in the middle sixteenth century (Russel-Wood, Reference Russel-Wood1998), but no average estimate is yet possible. What were the rewards that justified these perils? One way to answer this question is to reconstruct the set of push and pull factors that influenced the decision making by merchants and fishers.

One likely pull (attraction) was economic gain. In 1502, the first recorded landing of 36 metric tonnes of cod (saltfish) from Northwest (NW) Atlantic waters fetched a price of £180 (Pope Reference Pope2004a, p. 15). It is difficult to assess the actual financial reward of such an endeavour in the absence of business records, but we can gain some insight by simply converting to modern prices. Using the MeasuringWorth calculator, the relative value of £180 from 1500 equals labour earnings of £1.2 million in 2016 prices (Officer and Williamson, Reference Officer and Williamson2018). The economic power (wealth relative to total GDP) would be a staggering £75.9 million in modern value. These estimates, however crude, are sufficient to make the economic pull of Newfoundland cod stocks seem obvious. Indeed, in the past we have grossly underestimated the historical economic significance of the fish trade, which may have been equal to the much more famed rush to exploit the silver mines of the Incas (Pope, Reference Pope2004a).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY WAYS FORWARD

As momentous as this development was, the challenges to model and understand the ecological, economic, and wider social and cultural ramifications of the Fish Revolution are significant. In the words of the eminent historian Peter Pope (Reference Pope2004a, p. 21): “Like most early modern industries, the migratory cod fishery at Newfoundland was constrained by natural forces to an annual cycle no less than to long-term change in the climatic, economic, and diplomatic environments. This web is too complex to untangle with one tug.” We agree and believe that a full understanding of this complex web of marine ecosystems and human societies can only be obtained by multidisciplinary collaboration involving climate and marine science, as well as history and archaeology.

A satisfactory interpretation of the Fish Revolution must assess the relative importance of abiotic, biotic, and human variables. Although most of these factors would have been considered unknowable 10 or 15 years ago, ongoing breakthroughs in marine environmental history and historical ecology have moved information about both supply and demand sides of the equation into the realm of the discernible. Our knowledge of abiotic factors, such as temperature, wind, and currents, has increased tremendously in recent decades (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Ljungqvist, Luterbacher, Osborn, Briffa and Zorita2017). In addition, biotic factors such as primary production, fish abundance, and distribution can now be mapped, visualised, and analysed in tandem with social, cultural, political, and economic variables. On the human side, there is a long tradition of research and recently renewed interest in factors such as settlement, demography, capital, labour, and technology. Recent interest in consumption history has, moreover, sparked research into social and cultural food preferences and the factors of politics, strategy, and subsidies. A multidisciplinary approach facilitates reappraisal of major historical phenomena. Table 1 identifies variables in the complex web of the Fish Revolution that need untangling and call for a multifaceted approach.

Table 1. The web of factors and variables of the Fish Revolution.

WHAT WERE THE ENVIRONMENTAL PARAMETERS OF THE FISH REVOLUTION?

Ecological forces may have been just as important as economic ones. Sixteenth-century explorers remarked on the abundance of marine life in Newfoundland relative to home waters (e.g., Pope, Reference Pope2009), and indeed similar observations are made by seventeenth-century New England writers (Cronon, Reference Cronon2013). Bolster (Reference Bolster2013) argues that these observations indicate an already-severe depletion of European waters. He cites medieval evidence for population decline of right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) and grey whales (Eschrichtius robustus) in the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel, decline of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) and eider ducks (Somateria molissima) in the North Sea, and the depletion of sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) and salmon (Salmo salar) from European rivers and estuaries. Indeed, similar pressure was soon put on the NW Atlantic region. Between 1530 and 1620, Basque whalers in the Straits of Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador decimated right whale and bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) populations by killing tens of thousands of whales (Barkham, Reference Barkham1984). Later, between 1660 and 1701, Dutch and Basque whalers killed 35,000 to 40,000 whales in the western Arctic Ocean, causing considerable depletions of stocks and altering the whales’ migratory patterns (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Jeffrey and Mitchell1999). By contrast, the impact of pre-Columbian human pressure on marine life was considerably less. Although Native American Beothuk and Mi'kmaq communities in Newfoundland did prey on seals, porpoises (Phocoena), and gannets (Morus bassanus), it seems that cod fishing was minimal and that harvest rates were low relative to the scale of these marine resources, due to the available technologies and the comparatively limited level of access to offshore fishing grounds (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2011). Farther south, along the shores and estuaries of present-day New England, there is much evidence of the consumption of shellfish and riverine and marine fish (McKenzie, Reference McKenzie2011, pp. 13–14). Cod was fished in some quantities as early as 2000–1200 years ago in East Penobscot Bay, Maine (Belcher, Reference Belcher1989), and analysis of human collagen indicates a substantial consumption of marine food, primarily shellfish (Little and Schoeninger, Reference Little and Schoeninger1995). On balance, we agree with Bolster that European marine life in nearshore waters had been affected by AD 1500 to a degree that NW Atlantic shores had not.

However, in order to understand the choices confronting European fishers, the question must be whether human extractions had depleted major commercial fish species such as cod and herring in European waters to a degree sufficient to push fishers across the Atlantic. This seems highly unlikely. The largest and best-documented fishery of all is the Dutch North Sea herring fishery, which at a peak in AD 1602 extracted an exceptional 79,000 metric tonnes (Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2008). This was the single most closely managed and technologically advanced fishery of the world at this time. Other nations’ catches in the North Sea may be estimated at no more than half the Dutch based on preliminary investigations. To assess the impact of historical extractions, we can compare them with modern recommended total allowable catches (TACs). Through the 1990s and 2000s, the TAC of North Sea herring was in the interval of 180,000 to 300,000 metric tonnes (Simmonds, Reference Simmonds2007). Thus, total catches in the early modern period were consistently and considerably below those of the present day (Fig. 2). Indeed, 1602 was an exceptional year, and annual catches in the seventeenth century were mostly in the range of 20,000–50,000 tonnes, or at most 25% of today's recommended sustainable catch. The point is not that European catches were insignificant—certainly by the standards of the day the Dutch fishery was magnificent—but that their sustained efforts were likely insufficient to fish down the North Sea herring population according to present understandings.

Figure 2. Herring catch data in the North Sea by Dutch fishers, 1580–1920, including total allowable catches (TACs) range 1997–2007. Based on van Bochove (Reference van Bochove2004) and Poulsen (Reference Poulsen2008), International Council for the Exploration of the Seas recommended TAC. The y-axis units are in metric tonnes. Red line indicates lower TAC range; green line indicates upper TAC range.

Although European waters were not necessarily overfished, the waters of America still presented a bonanza—a pull to attract fishers across the Atlantic. But what exactly caused the attraction: Were NW Atlantic waters simply that much more productive than the European waters, even if their own status had not been markedly degraded, whether because of the intrinsic features of the NW Atlantic environment or the relatively lesser human extraction from these waters? The evidence as we currently have it indicates both. Seventeenth-century New Englanders did rave about the richness of the New World waters. Here they found an abundance and diversity of fish and specimens of a size that they had never seen before. The NW Atlantic is likely to have been more abundant than today because the ecosystem was relatively untouched. Global historical averages indicate that top predators were roughly 10 times more abundant in unimpacted ecosystems than what we observe today (Lotze and Worm, Reference Lotze and Worm2009). In a study of cod in the Gulf of Maine, Rosenberg et al. (Reference Rosenberg, Bolster, Alexander, Leavenworth, Cooper and McKenzie2005) found a 12-fold higher abundance of cod spawning stock biomass around 1852 relative to the average of the late twentieth century. Such superabundance may explain why in the late sixteenth century the combined efforts of French, Spanish, and Portuguese hook-and-line fishers were enough to extract a staggering 200,000 metric tonnes of cod from Newfoundland waters (Pope, Reference Pope2004a, Reference Pope2004b).

What were the ecological implications of this scale of extraction? Clearly, the ecosystem was productive enough to sustain large-scale fishery right up to the fatal collapse of the cod by the last decades of the twentieth century. On the other hand, the removal of biomass during the Fish Revolution will have had direct repercussions on top predators and longer-term impacts on the ecosystem that we are only beginning to understand. One previously ignored consequence of the fishery was the use of marine seabirds as bait as well as diet for resident fishing communities. It is estimated that as many as 70,000–80,000 birds were culled every year. Pope (Reference Pope2009) argues that the ecological side effects of the cod fishery included the demise of the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) and a substantial reduction of nesting places and populations of Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica), Common Murre also known as Guillemot (Uria aalge), and Northern Gannet (Morus bassanus). Woodland contraction was another ecological side effect (Pope, Reference Pope, Sicking and Abreu-Ferreira2008). On the other hand, the removal of substantial whale populations could have left much more food for top predator fish such as cod. Considerable work remains to understand the ecological consequences of the Fish Revolution.

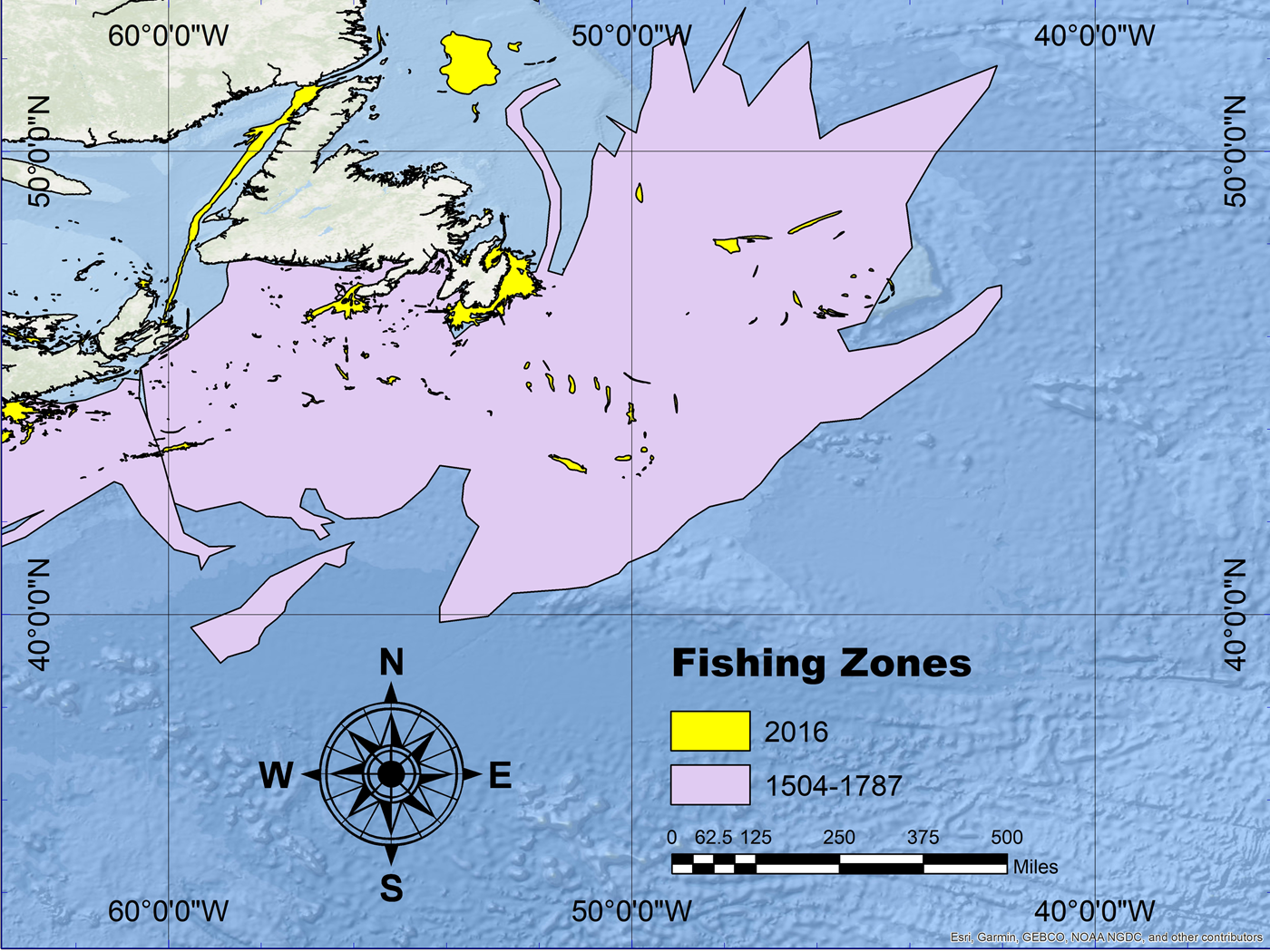

The contraction of Newfoundland and Grand Banks fishing areas between the time of the Fish Revolution and the present may be illustrated by comparing and contrasting historical and contemporary map data. Figure 3 shows the extent of the modern-day cod fishery and how it contrasts with the extent of early modern fishing activities based on 51 georectified historical maps dating between 1504 and 1787. Cod fishing expanded far and wide off the Newfoundland coasts in the early modern period, encompassing the riches of the Grand Banks, which were widely fished (see Fig. 3). Even assuming uncertainty in the accuracy of the available historical maps and the challenges inherent in the process of their georeferencing and visualization that may inflate the area apparently fished, it is abundantly clear that the geographic extent of the modern fishery in the region has contracted markedly.

Figure 3. Contraction of Northwest Atlantic fishery, 1504–1787 versus 2016. Conglomerated historic fishing areas are indicated by purple. Yellow indicates a snapshot of 2016 fishing areas. Sources: MarineTraffic, Advanced Vessel Filters (https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/home/ [accessed 2017]); Kroodsma et al. (Reference Kroodsma, Hochberg, Mayorga, Miller, Boerder, Ferretti and Wilson2018) and Global Fishing Watch (https://globalfishingwatch.org/our-map/ [accessed 2018]); Holm, P., Travis, C., Lougheed, K., Ludlow, F., Rankin, K.J., Legg, R., unpublished data [NorFish Historical Cartography & Fishery Data], 2018. Map by C. Travis, 2018.

To better understand the attraction of the NW Atlantic, we additionally need to understand how ocean productivity varied through time and, in particular, to elucidate the likely role of climate variability such as the Little Ice Age (LIA), the spatially variable downturn of Northern Hemisphere temperatures roughly between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. Much more is currently known about climatic changes and their underlying dynamics during this period than the marine palaeoenvironment per se. However, we can expect that the climatic volatility of the LIA (Matthews and Briffa, Reference Matthews and Briffa2005; Bradley, Reference Bradley2015) affected marine ecosystems. We know that modern ocean productivity can be highly regionalised (Prasad and Haedrich, Reference Prasad and Haedrich1993; Moll, Reference Moll1998). But how did the LIA affect regional productivity? Ólafsdóttir et al. (Reference Ólafsdóttir, Westfall, Edvardsson and Pálsson2014) found historical DNA indications of a decline of the coastal cod population around Iceland around AD 1500, possibly related to climate change. Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Pershing, Conversi, Planque, Hannah, Sameoto, Head, Smith, Reid, Jossi, Mountain, Benfield, Wiebe and Durbin2003) have shown that warmer waters are (at least for the Gulf of Maine) associated with greater primary biological productivity, whereas in the North Sea warmer waters are known to have the opposite effect. If the LIA acted to drive down temperatures across the Atlantic (e.g., Mann et al., Reference Mann, Zhang, Rutherford, Bradley, Hughes, Shindell, Ammann, Faluvegi and Ni2009; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yang, Ljungqvist, Luterbacher, Osborn, Briffa and Zorita2017; Fig. 4), we might infer that this exerted a downward pressure on potential biological productivity in the New World while having the opposite effect in Old World waters. This observation appears initially counterintuitive to the observed attraction of the Newfoundland waters to sixteenth-century fishers. We might thus further infer, at least provisionally, that whatever the influence of climate on the relative productivities of New and Old World waters, it was not of sufficient magnitude to meaningfully rebalance the suite of push and pull factors governing the decisions of European fishers. Future challenges lie, therefore, in testing the physical reality of the assumptions underlying the previous inferences and, ultimately, in reconstructing ocean productivity across the North Atlantic to better understand the role of total and relative biological production in the Fish Revolution.

Figure 4. The Atlantic Multidecadal Variability (AMV) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) as indicators for environmental change, 1400–1800. Available reconstructions are increasing in number and sophistication but still exhibit disagreements, as shown here in the available reconstructions of the AMO. Sources: Top panel, AMV from Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yang, Ljungqvist, Luterbacher, Osborn, Briffa and Zorita2017). Bottom panel, AMV with 30-yr smoothing from Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yang, Ljungqvist, Luterbacher, Osborn, Briffa and Zorita2017), and AMO from Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yang, Ljungqvist, Luterbacher, Osborn, Briffa and Zorita2017) and Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Zhang, Rutherford, Bradley, Hughes, Shindell, Ammann, Faluvegi and Ni2009).

The challenges of reconstructing the marine palaeoenvironment are considerable. Climate dynamics are driven by an interaction between internal variability and external (e.g., volcanic and solar) forcing, all having implications for marine conditions. Major explosive volcanic eruptions may, for example, influence North Atlantic productivity by multiple interacting mechanisms, including by directly cooling surface waters as well as altering ocean currents (location, velocity, mixing) and available light levels, both direct and diffuse (e.g., Robock, Reference Robock2000; Pausata et al., Reference Pausata, Chafik, Caballero and Battisti2015). All of these variables influence ocean productivity, beginning with the foundation of the food web in the abundance of light- and temperature-sensitive lower-trophic-level organisms such as phytoplankton and zooplankton (e.g., Legendre and Rassoulzadegan, Reference Legendre and Rassoulzadegan1995), with influences here cascading to successively higher trophic levels up to and including commercially valuable fish species such as cod and herring (Alheit et al., Reference Alheit, Licandro, Coombs, Garcia, Giráldez, Garcia Santamaría, Slotte and Tsikliras2014; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Bittner, Bryan, Carr, Hall, Jordaan and Klein2017). Only by resolving questions of the long- and short-term variability of ocean productivity, and understanding whether meaningful differences existed between the total productivities and relative trajectories of Northeast (NE) and NW Atlantic waters, will we be able to fully address the questions of how LIA climates mediated marine biomass production and ultimately untangle the ecological drivers of the Fish Revolution. Although such questions would have seemed unanswerable only a couple of decades ago, we are at the cusp of a breakthrough in marine palaeoscience that calls for a sustained inquiry with marine and climate scientists in dialogue with historians and archaeologists.

WHAT WERE THE GLOBALISING EFFECTS OF THE FISH REVOLUTION?

In this article, we use the concept of globalisation in a narrow definition to denote the integration between two continents—America and Europe—as driven by trade, human migration, knowledge and cultural exchange, and financial flows (International Monetary Fund, 2000). The environmental and ecological ramifications of globalisation (Worster, Reference Worster1988; Peters, Reference Peters2008)—such as biodiversity change, invasive species, evolving disease environments, and other health issues—may eventually be analysed in the context of the Fish Revolution. The rise of the NW Atlantic fishery had dramatic repercussions for the European fish market, which experienced a tripling of supplies of fish protein. Consumers had the choice of buying protein as meat or fish, as depicted in Figure 5, and the aggregated effect of their preferences would have ultimately driven fishing effort. To consumers in Europe, Newfoundland cod represented a novelty. The fish was large—up to 2 m in length—and the Newfoundland climate dried the fish well.

Figure 5. Lucas van Valckenborch (1535–1597), Meat and Fish Market (Winter), ca. 1595. Oil on canvas, 123.3 x 188 cm. Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Image used under Creative Commons.

The abundance of Newfoundland cod drove down the overall price of fish, but it still claimed a premium relative to unbranded or inferior products. We can trace the overall decline of the cod price in the purchasing power of the fishers. In AD 1500, 1 kg of Norwegian cod bought the fisher 8 kg of rye in the Bergen market. Only 50 years later, the same amount of fish bought just half this amount (Nedkvitne, Reference Nedkvitne1988). This decline continued relentlessly, as shown in Figure 6. To survive in such a market, you needed bulk, and bulk was what the Grand Banks offered.

Figure 6. Purchasing power of dried cod for rye in Bergen, Amsterdam, London, Münster, and Würzburg, 1270–1730. The y-axis units are kilograms of rye in exchange for 1 kg of dried cod. After Nedkvitne (Reference Nedkvitne1988, pp. 38, 42).

Not only was Newfoundland fish abundant, but consumers were willing to pay a premium for it, up to twice the price of locally sourced cod (Turgeon, Reference Turgeon and Williams2009). Regional control was enforced in the European markets, enabling customers to be confident in the uniform quality of the main commercial fish species (Unger, Reference Unger1978; Vickers, Reference Vickers1988; Wubs-Mrozewicz, Reference Wubs-Mrozewicz, Sicking and Abreu-Ferreira2009; Grafe, Reference Grafe2012). At a time of relative price decline, producers of better quality, volume, and durability stood to gain, but exactly how did the competition between Norwegian, Icelandic, and Newfoundland cod play out? The question raises a contested subject in understanding early modern markets: How efficient—or how integrated—were markets in early modern Europe? In other words, did Newfoundland and Norwegian cod compete in the same market, or did privileged access and consumer preference stall or indeed obviate the emergence of a common seafood market? The question of integration is important for understanding the full impact of the Fish Revolution—and indeed for understanding early modern economic growth (Persson, Reference Persson1999; Bateman, Reference Bateman2011).

The early modern European fish market operated under the influence of diverse factors, and a regional perspective does indicate that market integration was not a given. Norwegian producers had long-established contacts with the Hanseatic trading network that gave them easy access to the German and other continental markets (Wubs-Mrozewicz, Reference Wubs-Mrozewicz, Sicking and Abreu-Ferreira2009). French fishers developed a special commodity, the green or light-salted cod, which was preferred in France, while the Spanish fishers opened new markets in southern Europe for a heavily dried Newfoundland cod. The dried cod was ideal for the hot interior of Spain as it would endure long overland transportation (Grafe, Reference Grafe2012). Between 1580 and 1630, English suppliers eventually took over this market as they forced Iberian fishers from Newfoundland by means of competition and piracy.

When possible, fish merchants took opportunities to sell at different ports in pursuit of higher demand, though the gain of doing so was mediated by variable distances and transport costs (Grafe, Reference Grafe2012). Such behaviour acted to promote a greater integration of the European market and a convergence of prices between regions. Yet any evolving integration also contended with factors such as customs barriers, preferential treatment, and indeed politics and war that would have pushed the market towards fragmentation (Volckardt and Wolf, Reference Volckart and Wolf2004; Grafe, Reference Grafe2012). Questions about the resilience of contemporary globalized markets are now high on research agendas, notably focusing on how these markets may perform under exogenous shocks, whether from sudden moves towards protectionism, warfare, climate, or disease (e.g., Puma et al., Reference Puma, Bose, Chon and Cook2015; Gephart et al., Reference Gephart, Rovenskaya, Dieckmann, Pace and Brännström2016; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Carr, Dell'Angelo, Fader, Gephart, Kummu and Magliocca2016). It is often held that integrated markets should “perform” better by efficiently distributing food supplies from areas with surpluses to deficits, to prevent subsistence crises (van der Spek et al., Reference van der Spek, van Leeuwen and van Zanden2015). However, political, environmental, economic, and ideological complexities often interfere with the system-functional expectations of macroeconomic theory. Historical tests of the functioning of integrated markets are, therefore, urgently needed (Persson, Reference Persson1999; Bateman, Reference Bateman2011; Grafe, Reference Grafe2012). Cod is a suitable candidate commodity for testing these questions, as it originated from a few producers and traded as a well-defined quality product. Such research may focus on a concerted effort to map and assess the extent of market integration (in its rapidity, geography, and depth), how it was promoted or constrained by factors external to the market, how the market performed under shocks such as war or climate extremes, and how much this integration influenced the fortunes of European fishers and associated settlements.

WHAT WERE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE FISH REVOLUTION FOR FISHING COMMUNITIES?

The Fish Revolution affected fishing societies on both sides of the North Atlantic in opposite ways. In the NW Atlantic, new landscapes of at first migratory and later permanent mixed-ethnic settlements emerged in a landscape that had previously borne only a small indigenous population. In the NE Atlantic, the coastal landscape around 1500 was dotted with settlements, which by the seventeenth century were in decline. Distinct migratory pathways developed as a result, which conditioned the landscapes for the next couple of hundred years and in many ways are discernible even today.

Prior to the Fish Revolution, the late medieval commercial boom led to a rapid development of European fishing communities in both urban and rural contexts. A comprehensive review of the settlements remains to be undertaken, but it seems that urban fishing communities thrived on providing fresh fish for the town and local elites while also attracting merchant and estate capital to fit out vessels for long-distance operations. Urban fishing communities flourished in Ribe in Denmark (Holm, Reference Holm1999) and in Great Yarmouth, Scarborough, and Hull in England (Childs, Reference Childs2000), but nowhere more so than in the Low Countries in towns such as Dunkirk, Nieuwpoort and Ostend, Rotterdam, Schiedam, Vlaardingen, Maassluis, Brielle, and Enkhuizen (Sicking, Reference Sicking2002; van Bochove, Reference van Bochove2004). The Dutch developed a technological lead in North Sea herring fisheries that was begrudged but never successfully copied through this period by their competitors (Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2016b). Although the English herring fishery seems to have succumbed to Dutch competition by the fifteenth century, Hull developed a longline fishery off Iceland that lasted well into the seventeenth century (Childs, Reference Childs2000; Jones, Reference Jones and Starkey2000).

Rural coastal settlements—lacking a ready market—concentrated on nearshore fishing and produced dried and salted fish for sale at seasonal fairs in combination with other maritime activities such as trade, privateering (essentially piracy), and other coastal trades. The coastal settlements differed from the rural hinterland by including households of fisher-merchants with international contacts. They stand out in the archaeological record as particularly rich in imported goods and show a wealth in some households that make the settlements more akin to an urban than a rural context. The rural coastal settlements may be found all around northern European coasts of the Atlantic and (western) Baltic. They were clearly linked to the late medieval rise in income that was conditioned by the high fish prices of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Settlement took place on open lands, dunes, rocks, and moors, in close proximity to the sea and sometimes right by the beach. Although settlers cultivated small garden plots, the land was often largely unfit for agriculture. The settlers themselves are likely to have come from impoverished landless origins. The settlements often depended on capital provided by urban merchants and landed nobility who took an interest in developing maritime trade and even piracy out of barren soil (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Jørgensen and Mortensøn1981; Holm, Reference Holm1999; Fox, Reference Fox2001; Kowaleski, Reference Kowaleski2003).

The rural coastal settlements are significant for our understanding of the second phase of commercialisation of the fisheries. Fox (Reference Fox2001, pp. 186–187) interpreted the late-medieval settlements as “marginal economically because Acts of God (like storms and the disappearance of shoals from the inshore waters) could take away their inhabitants’ main means of making a living; and because they were especially prone to destruction by fire (closely huddled houses) and their people especially prone to plague.” A very different view is proposed by Goddard (Reference Goddard2011) who argues that thirteenth- and fourteenth-century small boroughs may be seen as “enterprise zones” within the English manorial economy. Goddard is not particularly concerned with coastal locations, but his considerations may be very pertinent to an understanding of their economic role. His model would fit an interpretation of the many rural ports of southwest England as a major factor in the English expansion into the Atlantic (Kowaleski, Reference Kowaleski2000).

Many of the marginal settlements were deserted or much reduced by the seventeenth century (i.e., after the onset of the Fish Revolution). We can identify local contraction and even abandonment of fishing in Norway, Denmark, Iceland, the Faroes, and Ireland. Archaeological and historical evidence shows that the Danish North Sea coast experienced a retraction of settlements to the inland (Holm, Reference Holm, Starkey and Hahn-Pedersen2002). In northern Norway, specialised coastal fishing settlements were abandoned, and people moved inland to pursue a multiplural economic subsistence that mixed farming and marine exploitation (Nielssen, Reference Nielssen, Barrett and Orton2016). In Iceland, fishing changed from being market led to being primarily for subsistence (Krivogorskaya et al., Reference Krivogorskaya, Perdikaris and McGovern2005; Edvardsson, Reference Edvardsson2010; Vésteinsson, Reference Vésteinsson, Barrett and Orton2016), and the primary export commodity shifted from fish to wool as was the case also on the Faroes (Gunnarsson, Reference Gunnarsson1983; Stoklund, Reference Stoklund1992). Urban fishing communities beyond the still-prospering Netherlands similarly seem to have declined.

This decline may be explained by multiple factors that are likely to have interacted in complex ways. Settlements in the Old World suffered from the Atlantic Fish Revolution (declining real prices of fish, increased fish supplies, and changing consumer demands), increased trade competition and piracy, and the global shipping revolution (increasing focus on port cities and long-distance trade). Others suffered dramatic flooding with coastal erosion and loss of settlements during the LIA (e.g., Lamb and Frydendahl, Reference Lamb and Frydendahl1991; Soens, Reference Soens2013). Their demise or transformation is indicative of a larger economic, social, and environmental pattern that remains to be fully researched.

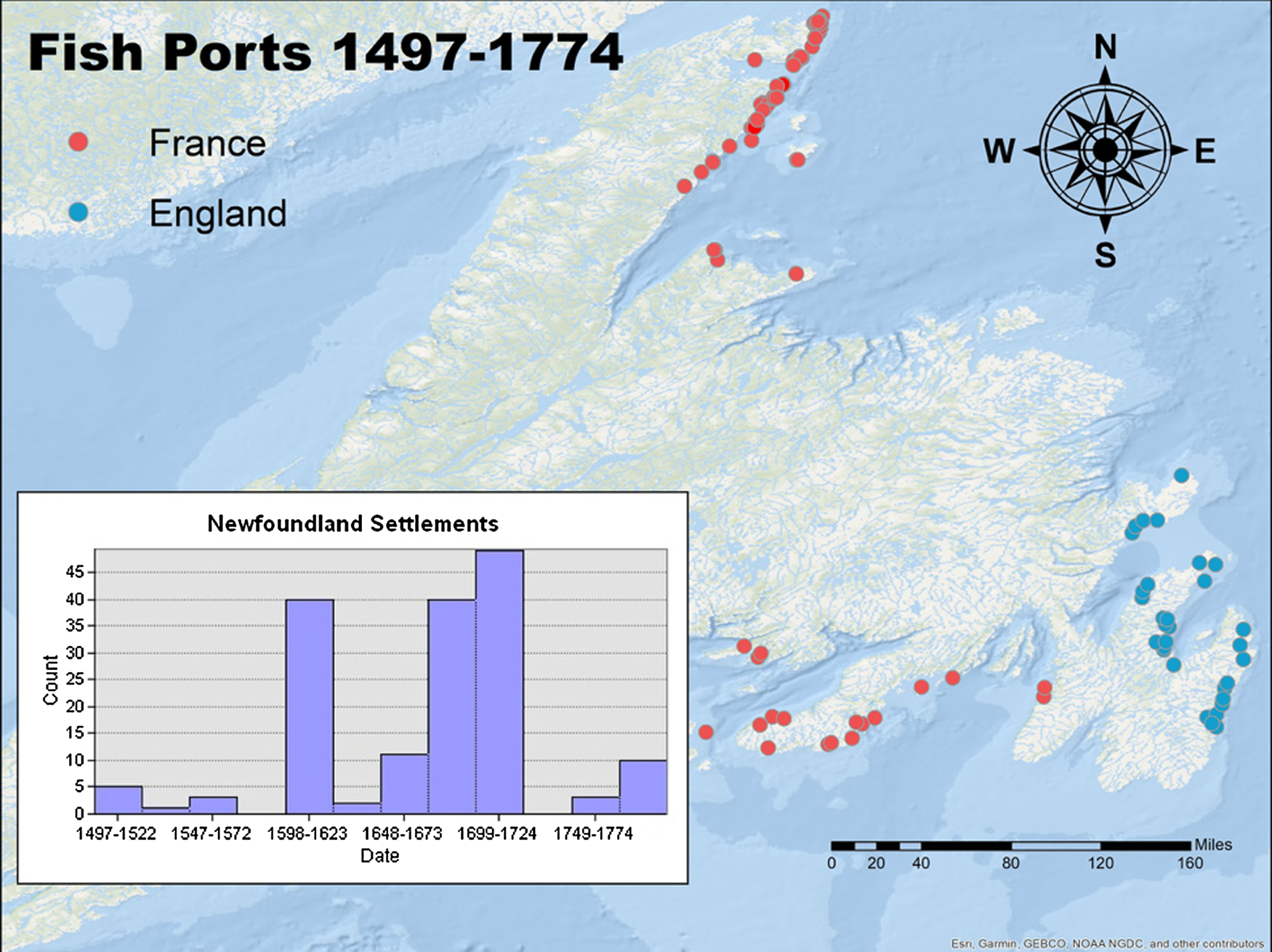

At the same time, settlements increased in Newfoundland. Archaeological traces of French settlers in the Petit Nord, and in southern Newfoundland, in addition to emerging English settlements in the southeast, showed a significant increase when seasonal return voyages of the labour force, typical of the sixteenth century, gave way to permanent settlements in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (see Fig. 7). The process was entangled with the differing political fortunes of the nations and peoples in question. Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, and French fishers had pioneered the Atlantic trade route as is evidenced by the surviving place names of the landscape and early cartography. Unfortunately, the details of this process are still obscure despite some pioneering research (Turgeon, Reference Turgeon and Williams2009; Grafe, Reference Grafe, Stern and Wennerlind2013; Barros, Reference Barros, Robinson, Wilcox and McCarthy2015). However, by the end of the sixteenth century, English fishermen and privateers succeeded in ousting the Iberian fishers, while the French succeeded in keeping the Petit Nord and southern coasts of Newfoundland into the mid-eighteenth century. Figure 7 shows the locations of French and British settlements and highlights that permanent migration took place most heavily in two distinct phases, 1598–1623 and 1699–1724.

Figure 7. Evidence of French fishing “rooms” in the northernmost peninsula (the Petit Nord) and in southern Newfoundland, in addition to English settlement in the southeast, 1497–1774. Sources: Tapper (Reference Tapper2014); P. Pope, personal communication 2016. Redrawn by C. Travis.

These changes in settlement patterns raise fundamental questions about the broader social and cultural impact of the Fish Revolution. Regions, such as Scandinavia, the NE Atlantic islands, and Germany, which failed to obtain access to the new fishing grounds in the NW Atlantic, saw a decline of home fisheries and a rise of an itinerant labour force as the European fisheries went into decline (Holm, Reference Holm, Starkey and Hahn-Pedersen2002; van Lottum, Reference van Lottum2007). Regions such as southwest England that did have access to Newfoundland saw a wave of emigration across the Atlantic (Matthews, Reference Matthews1968). In other words, we may be looking at two distinct patterns of labour migration as a result of the Fish Revolution. A full resolution of this picture will be of importance for understanding how coastal societies responded and adapted to the challenges of climate change and globalisation.

The Atlantic pathway points to the importance of overarching political rivalries and colonial contexts as the commercial interests of the Fish Revolution intensified. As a consequence of the Fish Revolution, perceptions of the North Atlantic changed, not only among fishers themselves but also within the European political, cultural, and economic hierarchy. Fishers were key witnesses for adventurers searching for both the Northwest and Northeast Passages and for prospectors searching for precious metals and valued commodities in the New World. Their information was filtered into the contemporaneous cartographic records, which now yield significant insights into what was known about fisheries and the related marine environment, while also reflecting the political and technological contexts underlying the production of maps. Through maps we can survey how evolving representations of Newfoundland reflected changing political and economic contexts over time, from early renderings by the Portuguese (e.g., Pedro Reinel's map, ca. 1504; Fig. 8) to maps reflecting the English/French rivalry over the fishery in the late seventeenth century, such as the 1693 chart of the coasts of Newfoundland and the Grand Banks by Augustine Fitzhugh (Fig. 9). While Fitzhugh shows the Grand Banks teeming with large French vessels, he depicts the small British boats in the inshore waters as literally besieged. The tensions underlying the political propaganda inherent in this map were eventually resolved with military confrontation and ultimately the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 (Ames, Reference Ames2008), which gave the British the undisputed upper hand in that most valuable asset of the “New World”, the Grand Banks.

Figure 8. Pedro Reinel (ca. 1462–1542), Portulan (Atlantic) (Portugal, ca. 1504). 62.0 x 89.3 cm. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich. (Digital copy is licensed under: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.)

Figure 9. Augustine Fitzhugh, A Chart of the Coasts of Newfoundland, with the Fishing Districts Marked…, 1693, London. Original 122 x 69 cm. © British Library Board (Additional MS. 5414.30).

CONCLUSION

The Fish Revolution is under-researched and indeed little appreciated as a major event in the history of resource utilisation and globalisation. Open research questions abound, especially those that pertain to the natural productivity and variability of fish stocks, the impact of changes in fisheries on coastal societies in Europe, and the relationship between changing fisheries and the politics and culture of European states. The challenge is finding effective ways to coordinate and integrate research into natural environmental variability, social science, and historical analysis. It involves working with very different kinds of data, each with its own appropriate scales, uncertainties, and relevance. It requires multidisciplinary teams that are motivated to collaborate and work towards finding the answers to common questions and problems, and it requires the development of theoretical frameworks capable of addressing complexity and multicausality.

By identifying the Fish Revolution as a major event in the history of resource extraction and consumption, bounded by climate change and globalisation, and by engaging in multidisciplinary research, we have highlighted and begun to address three key questions: (1) What were the environmental parameters of the Fish Revolution? (2) What were the globalising effects of the Fish Revolution? (3) What were the consequences of the Fish Revolution for fishing communities?

Much remains to be done, but we hope here to have identified a research agenda that will stimulate future multidisciplinary endeavours. Further and larger questions wait to be explored and answered in future work. For example: How was the change in fish consumption related to other changes, material and cultural, such as the access to other new foods (potatoes, maize, etc.) coming from the New World, and how significant were the fishing operations to the development of capital, politics, and cultural values of the period?

Fishing was not a glamorous activity; it was dangerous and dirty work. The industry developed between ca.1500 and 1700 with a transatlantic thrust of momentous economic, cultural, and political significance. Indeed, the Fish Revolution around 1500 permanently changed human and animal life in the North Atlantic region. The wider seafood market was transformed in the process, and the marine expansion of humans across the North Atlantic was conditioned by significant climatic and environmental parameters. The Fish Revolution is one of the clearest early examples of how humans can affect marine life on our planet and of how marine life can in return influence and become, in essence, a part of a globalising human world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is dedicated to the late Professor Peter Pope, Memorial University of Newfoundland, a pioneer of North Atlantic fisheries history. We were grateful to receive his support and insights in the early stages of this project. We acknowledge support from ERC Advanced Grant 669461. PH acknowledges support from the Program of High-End Foreign Experts and the Centre for Ecological History at Renmin University, China, during the final writing stage. PH and FL drafted the paper. CS, CT, RL and KL contributed numerical and GIS data and analysis. BA, CB, PWH, JAM, JN and KJR contributed material. RJB and JN performed database management. All authors read the paper and provided intellectual input.