Introduction

Although there are a number of studies on the physico-chemical properties and peroxidase-like activity of ferric heme b (= hemin) in micellar and vesicular systems, the current knowledge in this field is still rather limited. The reason for this primarily lies in the complexity of these systems and the many factors that determine the properties, for example the type of micelle- or vesicle-forming amphiphile used, its concentration, and the presence of other compounds that are expected to influence the catalytic power of hemin in a positive way. Some of the challenges that should be explored further emerge from a compilation of the results obtained so far. More fundamental studies toward a better understanding will help to judge the potential of hemin–micelle or hemin–vesicle systems as simple molecular assemblies for dedicated analytical or synthetic applications. In this Introduction and in the next section, clarifications about the terminology and abbreviations used are important, since they will be applied throughout the entire review.

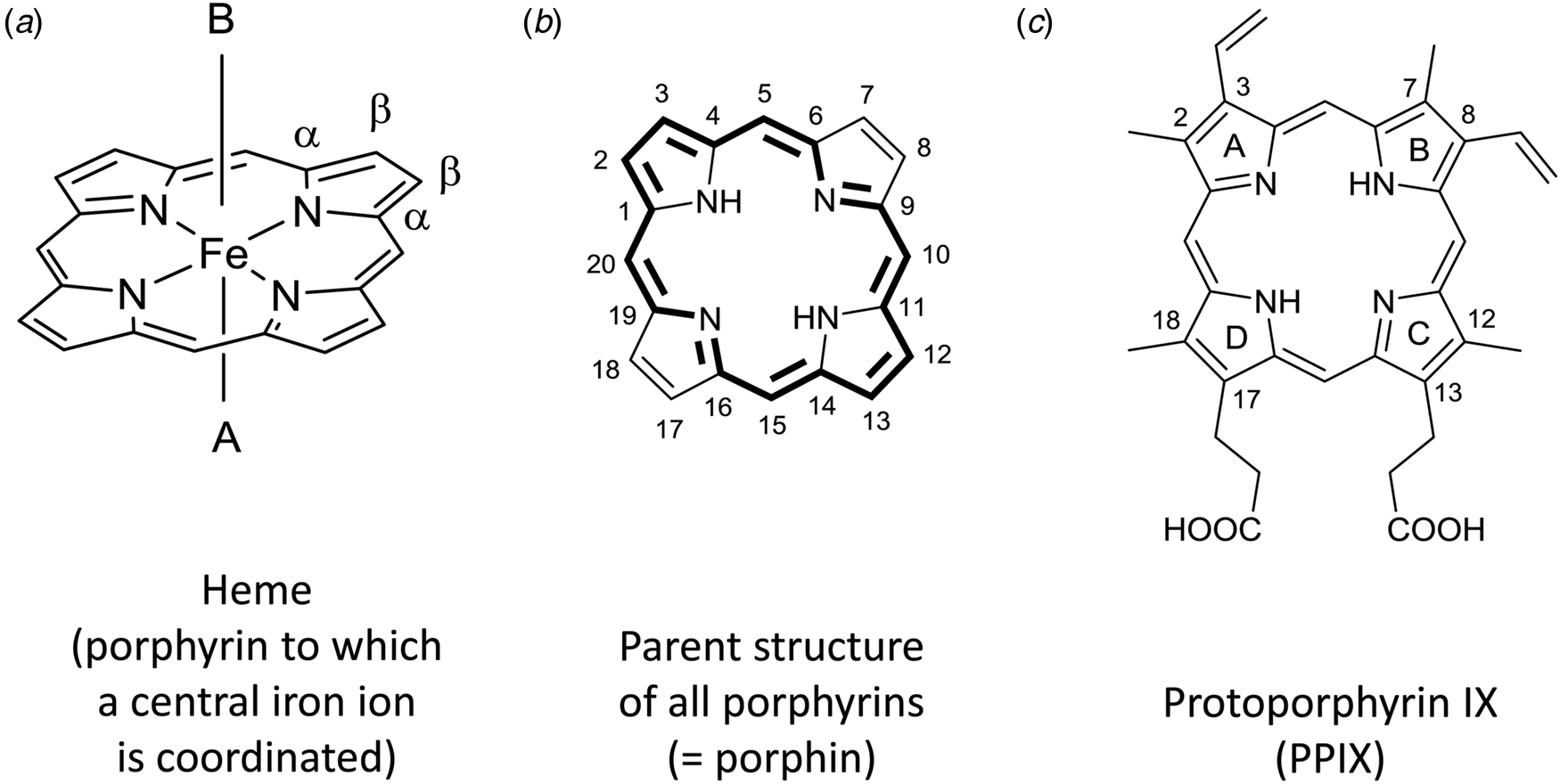

The term heme (American English) or haem (British English) refers to a coordination complex consisting of a central iron ion which (i) is coordinated to a porphyrin moiety as tetradentate ligand and (ii) may consist of one or two axial ligands (Fig. 1a) (Moss et al., Reference Moss, Smith and Tavernier1995). Heme is a metalloporphyrin in which the metal ion is iron, i.e. heme is an example of an iron porphyrin.

Fig. 1. (a) Chemical structure of heme consisting of an iron ion which is coordinated to the four nitrogen atoms of a planar macrocyclic porphyrin ring. The simplest porphyrin structure is shown, often called ‘porphin’, the parent structure of all porphyrins, with indication of the α- and β-positions of one of the four pyrrole units. A and B are the two axial ligands at the 5th and 6th coordination sites, respectively. In depictions of heme, A and B often are omitted, although they are essential for the biophysical properties of free heme and for the catalytic properties of heme as a prosthetic group in heme proteins. (b) Using the ‘1–24 atom numbering system’ for porphin (Moss, Reference Moss1988), all C-atoms at positions 2, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17, and 18 are connected to H-atoms; the base form of one of the two tautomers (before complexation with an iron ion) is drawn. All porphyrins are built from four pyrrole rings that are bridged via methine units and consist of 18 π-electrons that are delocalized (marked in bold). The two tautomers differ with respect to the location of the two N-bonded H-atoms, trans (shown) versus cis (Moss, Reference Moss1988). The methine units with C-atoms 5, 10, 15, and 20 are called meso-positions. In porphyrins different from porphin, one or more H-atoms in the β-positions of the pyrrole groups, at C-atoms 2, 3, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17, and/or 18, or at the methine carbons 5, 10, 15, and/or 20 are substituted by an organic residue. For naturally occurring porphyrins present in biological hemes, substitutions are possible at all mentioned positions. (c) Chemical structure of one of the four possible tautomers of the base form of protoporphyrin IX (= H2PPIX). As compared to the parent porphyrin structure shown in (b), a methyl group is at C2, C7, C12, and C18, an ethenyl (= vinyl) group at C3 and C8, and a propionic acid group at C13 and C17. To specify the four pyrrole rings, they are designated A, B, C, and D, as indicated. Upon metalation with Fe(II) or Fe(III), the two protons connected to the two nitrogen atoms in H2PPIX are released and the corresponding metalloporphyrin heme b is formed, (PPIX)FeII or [(PPIX)FeIII]+, see Fig. 2.

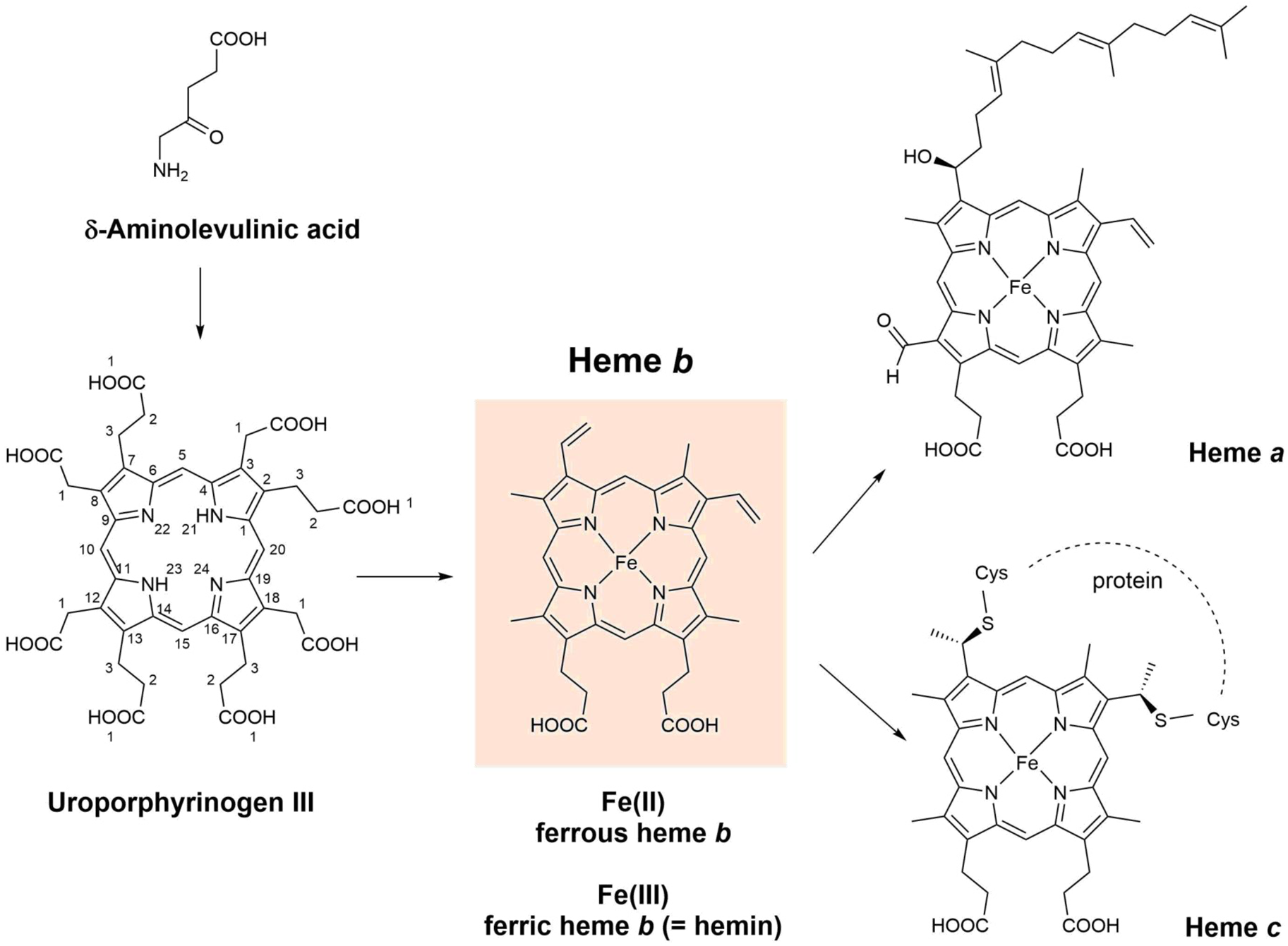

Fig. 2. Chemical structures of δ-aminolevulinic acid, uroporphyrinogen III, heme a, heme b (= iron protoporphyrin IX), and heme c. For the three known pathways of the biosynthesis of heme b (Kořený et al., Reference Kořený, Oborník, Horáková, Waller and Lukeš2022), δ-aminolevulinic acid and uroporphyrinogen III are the common intermediates. Biosynthetically, heme a and heme c are related to heme b (see Layer et al., Reference Layer, Reichelt, Jahn and Heinz2010; Hederstedt, Reference Hederstedt2012; San Francisco and Kranz, Reference San Francisco and Kranz2014; Niwa et al., Reference Niwa, Takeda, Kosugi, Tsutsumi, Mogi and Miki2018; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Grimm and Layer2019; Layer, Reference Layer2021; Kořený et al., Reference Kořený, Oborník, Horáková, Waller and Lukeš2022). Fe2+ coordinated to PPIX is called ferrous heme b, abbreviated as (PPIX)FeII, or (por)FeII (with por = PPIX). Fe3+ coordinated to PPIX is called ferric heme b, abbreviated as (PPIX)FeIII or (por)FeIII (with por = PPIX). Ferric heme b is also called hemin (Dunford and Stillman, Reference Dunford and Stillman1976). Often, the term ‘hemin’ is specifically used for (PPIX)FeIII(Cl), while (PPIX)FeIII(OH) is called hematin (or α-hematin) (see Omodeo-Salè et al., Reference Omodeo-Salè, Monti, Olliaro and Taramelli2001; Egan et al., Reference Egan, Chen, de Villiers, Mabotha, Naidoo, Ncokazi, Langford, McNaughton, Pandiancherri and Wood2006; Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009; Huy et al., Reference Huy, Shima, Maeda, Men, Hirayama, Hirase, Miyazawa and Kamei2013). Although shown in their neutral form, the two carboxylic acids of heme a, b, and c will be present in deprotonated form as well, depending on the local environment. DFT (density functional theory) calculations for free (PPIX)FeIII (= hemin) provided pK a values of 4.3 (= pK a1) and 5.6–6.4 (= pK a2) (see Durrant, Reference Durrant2014). Note that in this article, we do not distinguish between heme b (present as a prosthetic group in certain heme proteins) and heme B (the isolated, apoprotein-free form). Such distinction was suggested by Puustinen and Wirkström (Reference Puustinen and Wikström1991).

The general term porphyrin is used for the unsubstituted parent structure of all porphyrins shown in Fig. 1b, previously and often still called porphin, as well as for substituted porphyrins. The latter include any molecule made up of the core structure with C-bound hydrogen atoms (12 possible positions) substituted by alkyl, alkenyl, or other organic moieties (Park et al., Reference Park, Hong, Lee and Jang2021; Senge et al., Reference Senge, Sergeeva and Hale2021).

All porphyrins consist of a cyclic tetrapyrrole unit in which four pyrrole rings are linked at their α-positions (see Fig. 1a) via four methine bridges (–CH=, (Moss, Reference Moss1988)), forming a planar, aromatic macrocycle of 18 delocalized π-electrons. These delocalized electrons are responsible for the characteristic light absorption in the near ultraviolet and visible regions of the spectrum (Gouterman, Reference Gouterman1961), see below.

In addition to porphyrins, there are also a number of porphyrin derivatives (also called porphyrinoids) in which the core structure deviates from the one shown in Fig. 1b, for example with methylene bridges (–CH2–) instead of methine bridges, or with pyrrole rings that are linked without a bridging unit at all, as in the case of vitamin B12 (Moss, Reference Moss1988; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Smith and Tavernier1995, Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oh, Osuka and Kim2022).

For the most abundant porphyrin types present in biological hemes, all hydrogen atoms at the β-positions of the four pyrrole units (see Fig. 1a) are substituted. Depending on the chemical structures of the substituents and on their positions, different heme types result, called heme a, heme b, or heme c (Fig. 2), just to mention three of the most important ones (see e.g. Walker and Simonis, Reference Walker and Simonis2006). Differences between the three heme types exist in the substitutions at positions C3, C8, or C18. Heme c has two covalent thioether linkages to the apoprotein at C3 and C8 (made by cysteine residues of the protein). In the case of heme a, a hydroxyfarnesyl group is present at position C3, which makes the lipophilic part of heme more lipophilic than in the case of heme b. In addition, there is a formyl group at C18 that is easily oxidized to a carboxyl group, making heme a less stable than heme b upon extraction from biological systems (Hederstedt, Reference Hederstedt2012).

Hemes with substitutions at the methine positions are also known, but they will not be considered here. The focus of this review is on heme b (see Fig. 2). In heme b, the porphyrin to which an iron ion is coordinated is called protoporphyrin IX, abbreviated as PPIX (Fig. 1c). In the chemical structure of PPIX shown in Fig. 1c, the C-atoms are numbered according to the IUPAC/IUB recommendations of 1986 (Moss, Reference Moss1988; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Smith and Tavernier1995). The full numbering is given for the parent porphyrin structure shown in Fig. 1b.

Regardless of the great importance of PPIX (metalated and non-metalated), other porphyrin structures than PPIX as well as different porphyrinoids exist in living systems and play essential roles, including (i) in photosynthesis, (ii) for electron transfer processes, and (iii) as prosthetic groups in enzyme-catalyzed oxidation reactions (Lemberg, Reference Lemberg1954; Battersby, Reference Battersby2000; Dayan and Dayan, Reference Dayan and Dayan2011; Senge et al., Reference Senge, Sergeeva and Hale2021). This enormous importance of metalloporphyrins in biological systems explains the great interest in these metal-organic complexes. According to Senge et al. (Reference Senge, Sergeeva and Hale2021), from a purely physico-chemical point of view, the parent unsubstituted porphyrin structure shown in Fig. 1b is the most difficult porphyrin to work with, mainly due to its insolubility in many solvents, i.e. its strong propensity to self-associate into aggregates (Senge and Davis, Reference Senge and Davis2010). For this and other reasons, many different types of non-natural porphyrins have been synthesized in the past (Zipplies et al., Reference Zipplies, Lee and Bruice1986; Sitte and Senge, Reference Sitte and Senge2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Hong, Lee and Jang2021; Senge et al., Reference Senge, Sergeeva and Hale2021). They are being used as free porphyrins or as metalloporphyrins for fundamental studies, analytical and medical applications, as well as for the fabrication of functional materials (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Selbo, Weyergang, Dietze, Prasmickaite, Bonsted, Engesaeter, Angell-Petersen, Warloe, Frandsen and Høgset2005; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Song, Rieffel and Lovell2015; Sitte and Senge, Reference Sitte and Senge2020; Park et al., Reference Park, Hong, Lee and Jang2021; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang and Linhardt2021). In biological systems, heme is essential for the survival of virtually all types of organisms, including bacteria (Gallio et al., Reference Gallio, Fung, Cammack-Najera, Hudson and Raven2021). Heme is indispensable for the functioning of thousands of different proteins. More recently, evidence has been presented for the role of heme in ‘heme-responsive sensors’ that are involved in many important physiological functions, including heme-dependent transcriptional and translational regulation, tRNA synthesis, microRNA processing, heme-based potassium cation-channel regulation, and heme-based protein degradation (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Lengalova, Martínek and Martínková2019; Krüger et al., Reference Krüger, Keppel, Sharma and Frunzke2022). It is likely that hemes played at least some of these roles already in early cells, and porphyrins and hemes might have been present in prebiotic times, promoting photochemical processes and catalyzing chemical transformations in precellular compartment systems (often called ‘protocells’) (see e.g. Chen and Walde, Reference Chen and Walde2010; Monnard and Walde, Reference Monnard and Walde2015; Joyce and Szostak, Reference Joyce and Szostak2018; Toparlak and Mansy, Reference Toparlak and Mansy2019; Gözen et al., Reference Gözen, Köksal, Põldsalu, Xue, Spustova, Pedrueza-Villalmanzo, Ryskulov, Meng and Jesorka2022; Imai et al., Reference Imai, Sakuma, Kurisu and Walde2022).

Heme b is the simplest and most common heme type in biological systems (Bertini et al., Reference Bertini, Gray, Stiefel and Valentine2007). Therefore, often when ‘heme’ is mentioned in the literature without specification of the heme type, heme b is actually meant (see e.g. Kořený et al., Reference Kořený, Oborník, Horáková, Waller and Lukeš2022). There are three known biosynthesis routes that lead to heme b, with δ-aminolevulinic acid and uroporphyrinogen III (Fig. 2) as common intermediates (Layer, Reference Layer2021; Kořený et al., Reference Kořený, Oborník, Horáková, Waller and Lukeš2022). It seems that this diversity in heme b biosynthesis pathways is the result of an evolutionary optimization. In any case, heme b is present as a prosthetic group in the active site of many different types of heme proteins (also called hemoproteins) that perform astonishingly diverse functions, see the next section.

In ferrous heme b, Fe(II) is complexed to PPIX. Three different ways of abbreviating ferrous heme b are Fe(II)PPIX (= ferrous protoporphyrin IX), (PPIX)FeII, or (por)FeII, with ‘por’ standing for the porphyrin PPIX. These, or similar, abbreviations are often used in the literature (see e.g. Dunford, Reference Dunford2010; Campomanes et al., Reference Campomanes, Rothlisberger, Alfonso-Prieto and Rovira2015). In ferric heme b, Fe(III) is complexed to PPIX, abbreviated as Fe(III)PPIX (= ferric protoporphyrin IX), (PPIX)FeIII, or (por)FeIII (again with ‘por’ = PPIX). Ferric heme b is also known as hemin (Dunford and Stillman, Reference Dunford and Stillman1976), see Fig. 2. One way of specifying the type of axial ligands coordinating to the central iron ion as well as discriminating between mono- and bis-coordination (5th or 5th and 6th coordination sites, ligands A and B in Fig. 1a) is as follows: (PPIX)FeIII(Cl) in case one likes to emphasize that one chloride ion coordinates to ferric heme b; (PPIX)FeIII(OH) to indicate coordination of one hydroxyl group, or (PPIX)FeIII(DMSO,DMSO) for indicating the coordination of two dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) molecules. Often the term ‘hemin’ is used exclusively for (PPIX)FeIII(Cl), while (PPIX)FeIII(OH) is called hematin (or α-hematin) (see Omodeo-Salè et al., Reference Omodeo-Salè, Monti, Olliaro and Taramelli2001; Egan et al., Reference Egan, Chen, de Villiers, Mabotha, Naidoo, Ncokazi, Langford, McNaughton, Pandiancherri and Wood2006; Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009; Huy et al., Reference Huy, Shima, Maeda, Men, Hirayama, Hirase, Miyazawa and Kamei2013; de Villiers and Egan, Reference de Villiers and Egan2014; Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Mohunlal, Fitzroy, Asher, Smith, Egan and De Villiers2016). In this review, we do not make this differentiation. Hemin stands for any type of (PPIX)FeIII, independent from the chemical structure of the axial ligand(s). In experimental work, often (PPIX)FeIII(Cl) is used as a commercially available source of ferric heme b, sold as ‘hemin’. Dispersing (PPIX)FeIII(Cl) in aqueous NaOH solution will result in a rapid exchange of the chloride ion at the 5th coordination site forming (PPIX)FeIII(OH,H2O) or (PPIX)FeIII(OH,OH) (see Brown and Lantzke, Reference Brown and Lantzke1969).

In the following, we will first provide a brief overview of some heme proteins and their biological roles to illustrate the diversity of their functions. Then we will focus on the catalytic activity of selected heme b-containing enzymes (mainly heme b peroxidases). Afterward, two selected physico-chemical properties of hemin when dispersed or dissolved in an aqueous medium or in non-aqueous solvents will be discussed, followed by a summary of the current knowledge about the properties of hemin in micellar and vesicular systems. In that section it will be outlined why studies on the catalytic activity of hemin in the presence of micelles or vesicles are of interest. Some of the arguments discussed are in direct relation to the content of the succeeding section, which deals with the possible prebiotic presence of heme on the early Earth before life emerged from non-living forms of matter, at the origin of life. The final section provides conclusions about the entire field covered and a brief outlook on challenges that should be addressed in future studies. Figure 3 lists topics of interest in relation to research on heme b, including those highlighted in this review. A similar compilation of research topics could also be made for other hemes, as well as for metal-free porphyrins.

Fig. 3. Topics of interest in research on heme b (or other heme types), as highlighted in this review: (i) activity of heme b proteins in biological systems in terms of dependence of the activity on the oxidation state of the iron ion, the structure of the apoprotein, and the local environment of the protein-embedded heme group; (ii) physico-chemical properties of free heme b in aqueous and non-aqueous media; (iii) possible prebiotic formation of heme b; and (iv) preparation of heme b-based systems for mimicking the activity of heme b proteins. Understanding the physico-chemical properties of heme b helps understanding diseases caused by free heme b, designing heme b-protein mimics, and contributes to the discussion of scenarios concerning possible role(s) heme b might have played in prebiotic times.

Understanding the biophysical properties of free heme b is particularly useful for developing synthetic heme b-based catalytic systems that mimic the function of heme b proteins but do not contain a protein scaffold. Micellar and vesicular systems containing hemin belong to this category, see later Fig. 15.

The different roles of hemes in biological systems

Overview

The mere fact that the heme group – heme b, heme c, or another heme type – has many different functions in biological systems (in eukaryotes as well as in prokaryotes) not only underscores its importance, possibly already in early forms of life, but is also fascinating from a purely physico-chemical perspective. The key component of all hemes is the central iron ion with its ability to release or accept electrons, i.e. its redox properties, when an electron from ferrous bivalent iron is released to form ferric trivalent iron in a one-electron oxidation reaction, (por)FeII → (por)FeIII + 1 e−, with ‘por’ standing for any type of porphyrin, or when trivalent ferric iron is reduced to ferrous iron, (por)FeIII + 1 e− → (por)FeII. In addition, in catalytically active heme proteins the formation of tetravalent ferryl iron, oxoiron(IV), FeIV(=O) (see George and Irvine, Reference George and Irvine1956; Huang and Groves, Reference Huang and Groves2018) is an essential step, obtained in the case of heme peroxidases by a two-electron oxidation from ferric heme: (por)FeIII + H2O2 → (por+•)FeIV(O) + H2O (Dunford, Reference Dunford2010), see below.

Although iron is the second most abundant metal on Earth after aluminum (Williams and da Silva, Reference Williams and da Silva1997), free Fe2+ or Fe3+ are very toxic, and their concentrations in biological systems must be kept low; reactive oxygen species can form, for example the hydroxyl radical (HO•) or the superoxide radical anion (O2•−) (see Crielaard et al., Reference Crielaard, Lammers and Rivella2017; Eid et al., Reference Eid, Arab and Greenwood2017; Muckenthaler et al., Reference Muckenthaler, Rivella, Hentze and Galy2017; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Lengalova, Martínek and Martínková2019; Katsarou and Pantopoulos, Reference Katsarou and Pantopoulos2020). Upon complexation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ to porphyrins, for example PPIX, the formed iron porphyrin complex remains toxic. Some of the reasons for the toxic effect of free hemin are (i) its interaction with biological membranes causing changes in the fluidity and permeability (Kumar and Bandyopadhyay, Reference Kumar and Bandyopadhyay2005; Qutub et al., Reference Qutub, Uzunova, Galkin and Vekilov2010), and (ii) the hemin-catalyzed degradation of proteins and the formation of modified lipids including lipid peroxides, resulting in an alteration of the membrane properties (Kumar and Bandyopadhyay, Reference Kumar and Bandyopadhyay2005; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Dang, Dringen and Bishop2009). This explains why the concentration of free heme b in living systems (ca. 25–300 nM in mammalian cells, see Donegan et al., Reference Donegan, Moore, Hanna and Reddi2019) is tightly regulated by O2-dependent heme oxygenase systems and through the formation of non-toxic heme–protein complexes (involving e.g. albumin) (Kumar and Bandyopadhyay, Reference Kumar and Bandyopadhyay2005; Unno et al., Reference Unno, Matsui and Ikeda-Saito2007; Matsui et al., Reference Matsui, Unno and Ikeda-Saito2010).

There are various dedicated biological functions of heme, enabling (i) certain oxidation reactions to occur selectively (e.g. in the case of heme peroxidases, catalases, cytochrome P450, or nitric oxide (NO) synthase), (ii) electron transfer reactions (e.g. in the case of cytochrome c), or (iii) the transport and storage of gaseous molecules (the case of hemoglobin (Hb) and myoglobin (Mb)). The hemes may even act (iv) as signaling agents in heme-responsive sensors, or (v) as heme-based gas sensors. This diversity of functions in contemporary forms of life might provide a hint for the importance of hemes in early cells and possibly before the first cells emerged. These diverse functions of hemes in biological cells are illustrated with a few examples.

Conceptually, the involvement of heme in the different biological functions can be grouped in two categories.

The first category consists of heme proteins with either a covalently bound heme group (e.g. heme c in cytochrome c), or a non-covalently associated heme group (e.g. heme b in Mb, Hb, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), catalase, NO synthase (NOS), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), or cytochrome P450), see Fig. 4. All these heme b proteins have different functions, see Table 1. In the case of heme-based gas sensors, which also belong to this category, binding of a gaseous molecule to the heme group in the ‘sensor module’ (a specific domain of the protein) results in a change of the activity at the ‘catalytic module’ (another, spatially separated domain of the protein). This occurs due to bound gas molecule-induced conformational changes that are transmitted from the ‘sensor module’ via the ‘transducer module’ (a third protein domain) to the ‘catalytic module’. Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) is one such example (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Liu, Wu and Chen2019), schematically shown in Fig. 5. In this case the sensor molecule is NO, and binding occurs to ferrous heme b.

Fig. 4. (a) Crystal structures of selected examples of heme proteins containing heme b: sperm whale myoglobin (Mb), horse deoxy hemoglobin (Hb), human catalase, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, the heme domain of rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and human cytochrome P450. (b) Details of the active site of the crystal structure of HRP, with (PPIX)FeIII (= hemin) non-covalently bound to a hydrophobic pocket formed by the apoprotein. The two carboxylates of hemin are localized at the periphery of HRP. The positions of the proximal His170, distal His42, and distal Arg38 and the existence of an extended H-bond network are emphasized, as reported by Smulevich et al. (Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005) (see also Veitch, Reference Veitch2004; Battistuzzi et al., Reference Battistuzzi, Bellei, Bortolotti and Sola2010). The H-bond between His170 and Asp247 (Smulevich et al., Reference Smulevich, Paoli, Burke, Sanders, Thorneley and Smith1994) seems to contribute to the reactivity of HRP by increasing the electron donating properties of His170 (see Ortmayer et al., Reference Ortmayer, Fisher, Basran, Wolde-Michael, Heyes, Levy, Lovelock, Anderson, Raven, Hay, Rigby and Green2020). (b) Reprinted with permission from Smulevich et al. (Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005), Copyright 2005 American Chemical Society.

Fig. 5. Example of a heme-based gas sensor: soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC). (a) Schematic representation of the conformational changes during the activation of human sGC by gaseous nitric oxide (NO) generated by NOS from l-Arg and O2 (see Table 1), as reported by Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Liu, Wu and Chen2019). sGC is a heterodimeric protein complex composed of one α-subunit and one β-subunit; H-NOX is the sensor domain (‘sensor module’), which consists of ferrous heme b, (PPIX)FeII (labeled ‘Haem’), able to bind NO (and O2 or CO, similarly to Hb and Mb). NO binding to β1 H-NOX triggers structural rearrangements and conformational changes that affect the catalytic domains (CD, ‘catalytic module’), resulting in a boosting of the catalytic activity of sGC (see Derbyshire and Marletta, Reference Derbyshire and Marletta2012; Herzik et al., Reference Herzik, Jonnalagadda, Kuriyan and Marletta2014; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Liu, Wu and Chen2019). The other two domains shown are the PAS (Per/ARNT/Sim) domain and the CC (coiled-coil) domain (‘transducer module’). (b) Ribbon drawing for the heme-binding domain β1 H-NOX in sGC of the moth Manduca sexta, as reported by Montfort et al. (Reference Montfort, Wales and Weichsel2017). (PPIX)FeII is shown as stick representation. C-atoms are drawn in black, N atoms in blue, and O atoms in red. His105 is the proximal axial ligand that coordinates to Fe(II). After binding of NO to (PPIX)FeII, the bond between Fe(II) and the proximal His105 is broken, which results in conformational changes (Herzik et al., Reference Herzik, Jonnalagadda, Kuriyan and Marletta2014; Montfort et al., Reference Montfort, Wales and Weichsel2017; Wittenborn and Marletta, Reference Wittenborn and Marletta2021). The reaction catalyzed by sGC in the CD domain is: GTP (guanosine 5′-triphosphate) → GMP (cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate) + PPi (inorganic pyrophosphate = diphosphate) (see Denninger and Marletta, Reference Denninger and Marletta1999). Reproduced with permission from (a) Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Liu, Wu and Chen2019), Springer Nature and (b) Montfort et al. (Reference Montfort, Wales and Weichsel2017), Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

Table 1. Examples of the biological function of selected heme proteins containing heme b (Bertini et al., Reference Bertini, Gray, Stiefel and Valentine2007; Efimov et al., Reference Efimov, Basran, Thackray, Handa, Mowat and Raven2011; Ortiz de Montellano, Reference Ortiz de Montellano and Lyubimov2012; Poulos, Reference Poulos2014; Huang and Groves, Reference Huang and Groves2018; Cinelli et al., Reference Cinelli, Do, Miley and Silverman2020)

The second category, to which the heme-responsive sensors belong, consists of proteins that do not have a heme group, but instead carry a binding site for heme (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Lengalova, Martínek and Martínková2019; Krüger et al., Reference Krüger, Keppel, Sharma and Frunzke2022). Upon binding of free heme to this binding site, conformational changes in the protein occur, resulting in a change of the protein properties. One example is the membrane-embedded potassium ion channel Kv1.4, as schematically shown in Fig. 6 (Sahoo et al., Reference Sahoo, Goradia, Ohlenschläger, Schönherr, Friedrich, Plass, Kappl, Hoshi and Heinemann2013; Burton et al., Reference Burton, Kapetanaki, Chernova, Jamieson, Dorlet, Santolini, Moody, Mitcheson, Davies, Schmid, Raven and Storey2016; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Lengalova, Martínek and Martínková2019). Binding of heme b to Kv1.4 results in conformational changes that prevent closing of the channel so that the permeation of potassium ions for the heme b-bound channel protein is increased if compared to the same channel protein without heme b.

Fig. 6. Example of a membrane-bound heme-responsive sensor: voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channel Kv1.4. (a) Cartoon representation of the interaction of free ferrous or free ferric heme b, (PPIX)FeII or (PPIX)FeIII (red diamond symbol), with membrane-bound Kv1.4, as summarized by Burton et al. (Reference Burton, Kapetanaki, Chernova, Jamieson, Dorlet, Santolini, Moody, Mitcheson, Davies, Schmid, Raven and Storey2016), based on the experimental results reported by Sahoo et al. (Reference Sahoo, Goradia, Ohlenschläger, Schönherr, Friedrich, Plass, Kappl, Hoshi and Heinemann2013). Heme b binds to the N-terminal domain of the channel protein and impairs an inactivation process that is known to occur in the absence of heme b. In this way, heme b acts as a regulator of the potassium ion channel activity of Kv1.4. The investigations showed that the heme b-responsive binding motif in the N-terminal domain most likely involves His16 and His35, as well as Cys13. Heme b binding induces a conformational constraint that prevents the N-terminal inactivation domain from reaching its receptor site at the vestibule of the channel pore (see Sahoo et al., Reference Sahoo, Goradia, Ohlenschläger, Schönherr, Friedrich, Plass, Kappl, Hoshi and Heinemann2013). The cell membrane is depicted in pale blue and the intracellular side is at the bottom. The light purple rectangles depict the conduction pore of the Kv1.4 channel. The dark purple rectangles are the voltage sensor domains in the Kv1.4 channel. Other transmembrane domains have been omitted for simplicity (see Burton et al., Reference Burton, Kapetanaki, Chernova, Jamieson, Dorlet, Santolini, Moody, Mitcheson, Davies, Schmid, Raven and Storey2016). (b) Using a recombinant 61 amino acid long peptide with the sequence of the N-terminal inactivation domain and NMR spectroscopy, the peptide conformation and the binding of heme b to the peptide through the imidazole rings of His16 and His35, coordinated at the 5th and 6th coordination positions of Fe(II) or Fe(III), is illustrated. Adopted from Sahoo et al. (Reference Sahoo, Goradia, Ohlenschläger, Schönherr, Friedrich, Plass, Kappl, Hoshi and Heinemann2013). Reproduced with permission from (a) Burton et al. (Reference Burton, Kapetanaki, Chernova, Jamieson, Dorlet, Santolini, Moody, Mitcheson, Davies, Schmid, Raven and Storey2016) and (b) Sahoo et al. (Reference Sahoo, Goradia, Ohlenschläger, Schönherr, Friedrich, Plass, Kappl, Hoshi and Heinemann2013).

The fact that heme proteins composed of the very same heme group can have diverse activities is surprising at first glance, but can be understood by considering the molecular complexities of the heme-binding domain of the different apoprotein structures in which the heme group is embedded. These local apoprotein features must be taken into account if one aims to mimic a certain heme b protein function by placing heme b in a non-natural environment. Selected examples of heme b-containing proteins are given in Fig. 4 and Table 1. There are at least five factors which determine the activity at the heme group of heme b proteins.

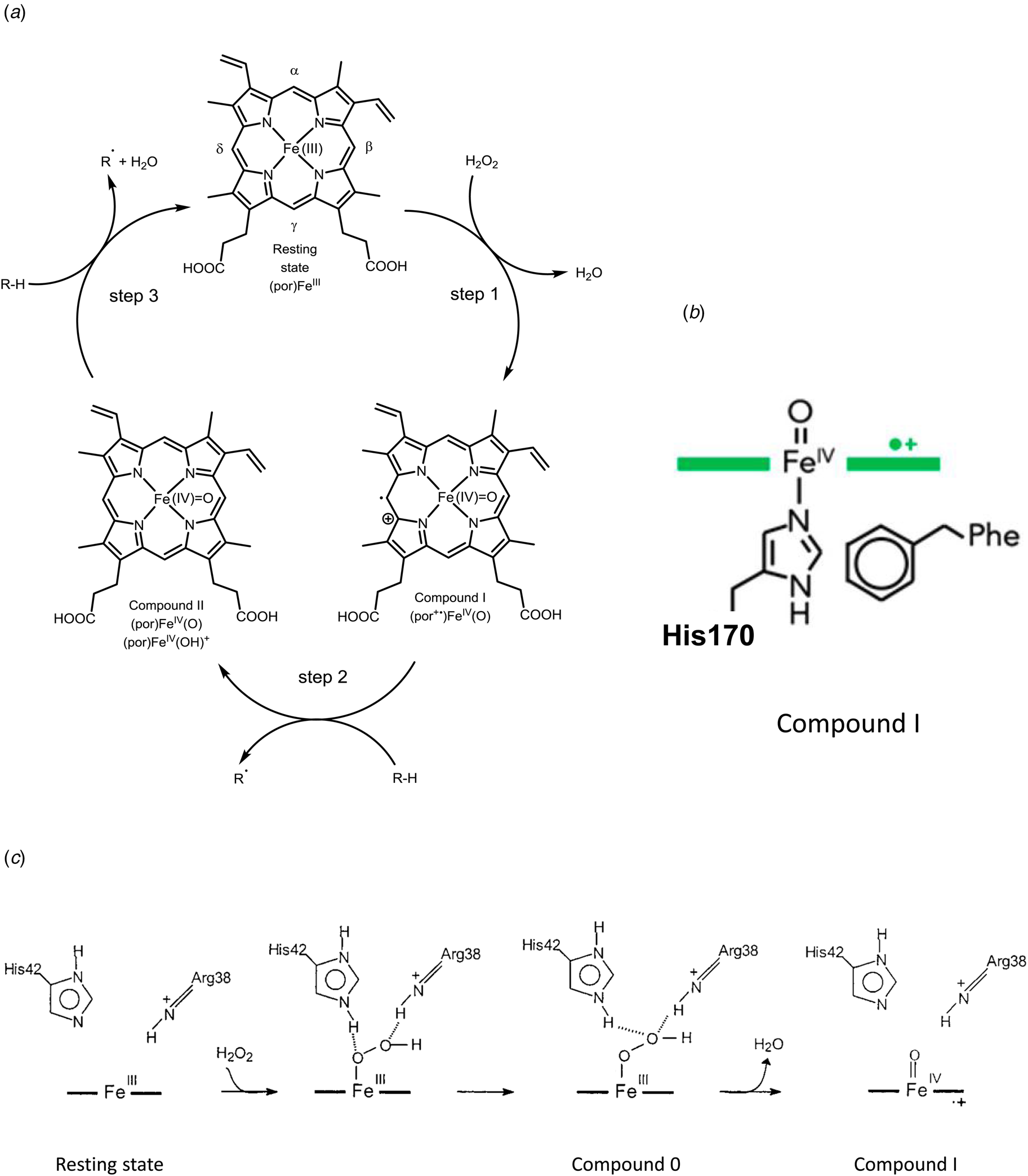

The first factor is the oxidation state of the iron ion. For the binding of O2 to heme b in Hb, Mb, or IDO, the iron ion must be in ferrous state, i.e. heme b must be (PPIX)FeII, embedded in the appropriate environment of the apoprotein (see Jensen and Ryde, Reference Jensen and Ryde2004; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Roos and Ryde2005; Shikama, Reference Shikama2006). The same is true for NOS, when NO binds to heme b, or for cytochrome P450, when O2 binds. Since in both cases, the resting state of the enzyme contains ferric heme b, (PPIX)FeIII, a reduction of (PPIX)FeIII to (PPIX)FeII must precede the binding of these gaseous molecules to the enzymes (Guengerich, Reference Guengerich2018; Jeffreys et al., Reference Jeffreys, Girvan, McLean and Munro2018; Tejero et al., Reference Tejero, Hunt, Santolini, Lehnert and Stuehr2019; Cinelli et al., Reference Cinelli, Do, Miley and Silverman2020). In the case of the catalytic cycle of cytochrome P450, for example, ferric heme b of the resting state of the enzyme is first reduced to the ferrous state, involving NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form) or NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced form) and a reductase. Moreover, after binding of O2 to the intermediate (PPIX)FeII, for an oxidation of the substrate to occur, a further reduction of (PPIX)FeII containing bound O2 is required by the delivery of an electron from an electron donor partner (Ortiz de Montellano, Reference Ortiz de Montellano and Lyubimov2012; Jeffreys et al., Reference Jeffreys, Girvan, McLean and Munro2018). Then, after protonation, O2 is heterolytically cleaved, resulting finally in the oxidation of the substrate, e.g. octane is oxidized to octan-1-ol (‘R’ and ‘RO’, respectively in Table 1). Overall, the catalytic cycle of cytochrome P450 is very complex and, therefore, it is very challenging to mimic it in vitro with a heme b system that lacks the apoprotein and the other cofactors and enzymes required for the functioning of the enzyme in vivo. The same can be said for NOS as an example. In the case of HRP, however, the catalytic cycle is ‘simpler’ since ferric heme b, (PPIX)FeIII of the resting state can directly be activated (oxidized) by H2O2 as a terminal oxidant (Berglund et al., Reference Berglund, Carlsson, Smith, Szöke, Henriksen and Hajdu2002; Dunford, Reference Dunford2010), see Fig. 7a. Therefore, there are many attempts to mimic the activity of HRP by using isolated ferric heme b (= hemin).

Fig. 7. Peroxidase cycle of HRP. (a) Schematic representation of the three steps of the peroxidase cycle of heme peroxidases like HRP (see e.g. Torres et al., Reference Torres, Bustos-Jaimes and Le Borgne2003; Campomanes et al., Reference Campomanes, Rothlisberger, Alfonso-Prieto and Rovira2015; Cvjetan et al., Reference Cvjetan, Kissner, Bajuk-Bogdanović, Ćirić-Marjanović and Walde2022). Step 1 is the two-electron oxidation of HRP in its resting state (with the ferric heme b group, (por)FeIII, por = PPIX) by H2O2, which yields compound I (por+•)FeIV(O), with a π-cation radical on the porphyrin ring. In this first step, H2O2 must be able to reach Fe(III) at the distal site. In step 2, compound I oxidizes the reducing substrate (R-H, e.g. phenol, see Table 1) in the solvent-exposed δ-region of the heme group in an one-electron oxidation reaction to yield the substrate radical R• (e.g. phenol radical, see Table 1) and compound II (por)FeIV(O) or (por)FeIV(OH)+ (see Derat and Shaik, Reference Derat and Shaik2006; Campomanes et al., Reference Campomanes, Rothlisberger, Alfonso-Prieto and Rovira2015). With step 3 – another one-electron oxidation of R-H at the δ-region of the heme group – the cycle is closed and the resting state of HRP is again obtained. Overall stoichiometry: 2RH + H2O2 → 2R• + 2H2O. (b) Key intermediate ‘compound I’. Illustration of the coordination of the proximal His170 to oxoferryl PPIX as a radical cation (green) (see Moody and Raven, Reference Moody and Raven2018). (c) Mechanism of the formation of compound I in HRP, occurring at the distal side of (por)FeIII, as described by Rodriguez-López et al. (Reference Rodríguez-López, Lowe, Hernández-Ruiz, Hiner, García-Cánovas and Thorneley2001) for neutral or basic pH (neutral His42). (b) Reproduced with permission from Moody and Raven (Reference Moody and Raven2018), Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. (c) Adapted with permission from Rodriguez-López et al. (Reference Rodríguez-López, Lowe, Hernández-Ruiz, Hiner, García-Cánovas and Thorneley2001), Copyright 2001 American Chemical Society.

The second factor is the chemical structure of the electron donating functional group of the amino acid side chain of the apoprotein that coordinates to the heme group axially at the 5th coordination site, the ‘proximal side’, for example a thiol of a cysteine (e.g. in the case of cytochrome P450 or NOS), the imidazole group of a histidine (e.g. in the case of Hb, Mb, HRP, or IDO), or the phenolic hydroxy group of a tyrosine (e.g. in the case of human catalase), see Table 1.

The third factor is the functional groups present at the ‘distal side’ of the heme group, opposite to the proximal side. In the case of HRP, the side chains of a distal histidine and a distal arginine are important for the efficient oxidation of ferric heme b by H2O2 to compound I (a powerful oxidant), with a FeIV=O oxoferryl group in the center of the porphyrin and a π-cation radical on the porphyrin PPIX, (por+•)FeIV(O) (Fig. 7b). The reported reduction potential of the compound I/compound II couple is 880–900 mM (referenced to the standard hydrogen electrode) (see Torres and Ayala, Reference Torres and Ayala2010).

The fourth factor is the accessibility of the heme group for the substrate molecules that need to reach the heme group. One example is the accessibility of H2O2 at the 6th coordination site of heme b in HRP in the first step of the catalytic cycle (Rodríguez-López et al., Reference Rodríguez-López, Lowe, Hernández-Ruiz, Hiner, García-Cánovas and Thorneley2001) (Fig. 7c). The apoprotein structure in the vicinity of the distal side of the heme group allows the oxidizing substrate, H2O2, to approach Fe(III). Furthermore, if the 6th coordination site would be blocked by a strongly coordinating ligand (Durrant, Reference Durrant2014), H2O2 would not be able to bind to the iron ion, so that the required formal transfer of two electrons from the heme group to the bound O-atom and a heterolytic cleavage of the peroxo (–O–O–) bond in H2O2 to form compound I, (por+•)FeIV(O) (Vidossich et al., Reference Vidossich, Fiorin, Alfonso-Prieto, Derat, Shaik and Rovira2010) would not occur, see Fig. 7c. The formation of compound I as an intermediate of the peroxidase cycle of HRP, as well as the formation of compound II is reflected in the absorption spectrum of HRP in the Soret and Q-band regions of the spectrum, see Fig. 8. The reported reduction potential of the compound II/Fe(III) couple is 870–900 mV (referenced to the standard hydrogen electrode) (see Torres and Ayala, Reference Torres and Ayala2010).

Fig. 8. (a) UV/vis absorption spectra of the resting state of HRP (‘native’) and of the two intermediates of the peroxidase cycle, compound I (‘I’) and compound II (‘II’), as reported by Dunford (Reference Dunford2010). The Soret-band region of the spectrum is shown on the left-hand side, the much less intense Q-band region on the right-hand side. Native HRP is brown, compound I is green, and compound II is red. The molar absorptions are given for HRP isoenzyme C (HRPC), the most abundant isoenzyme of HRP, λ 403 (native HRP) = 1.02 × 105 M−1 cm−1 (see Dunford, Reference Dunford2010). Similar spectra were obtained at pH = 5 by Sumithran et al. (Reference Sumithran, Sono, Raner and Dawson2012) and at pH = 10.7 by Hewson and Hager (Reference Hewson and Hager1979). Furthermore, Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Sanders, Thorneley, Burke and Bray1992) showed that the absorption spectrum of native (glycosylated) HRPC (measured at pH = 7.0) and the peroxidase activity are very similar to the spectrum of recombinant (non-glycosylated) HRPC; indicating an insignificant influence of the glycosidic chains on the structural properties of the heme group and on the activity of purified HRP, at least at pH = 7.0. (b) Dependence on pH of the UV/vis absorption spectrum of H170A hHRP (10 μM), a mutant of native HRP in which the proximal histidine (His170, see Fig. 4b) was replaced by alanine, as reported by Newmyer (Reference Newmyer1996) and Newmyer et al. (Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996); ‘hHRP’ indicates the presence of a terminal polyhistidine tag in the mutant. Solid line: pH = 4, (0.1 M acetate); dotted line: pH = 5 (0.1 M phosphate); short dashed line: pH = 6 (0.1 M phosphate); long dashed line: pH = 7.0 (0.1 M phosphate) (see Newmyer, Reference Newmyer1996). The strong pH-dependency of the spectrum seems to reflect binding of distal His42 and H2O or HO− to Fe(III) (see Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). The pattern in the Q-band region indicates hexacoordination of Fe(III), see Fig. 18a. (a) Reproduced with permission from Wiley. (b) Reprinted with permission from Newmyer et al. (Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996), Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

The fifth factor is the local heme b environment in terms of (i) the hydrophilic parts of heme b that are exposed to the bulk aqueous solution, (ii) electrostatic interactions between amino acid residues of the apoprotein and the two propionic acid groups of heme b, and (iii) the hydrophobicity as well as the local charges around the porphyrin core of heme b. All of these interactions, together with the second and third factors mentioned above, have a significant influence on the redox potential of heme b. For heme proteins, the impact of each factor on the redox potential was ranked as follows: axial coordination (280 mV), metalloporphyrin type (245 mV), heme burial (36–138 mV, up to 500 mV), and local charges (40–135 mV, up to 200 mV) (Reedy and Gibney, Reference Reedy and Gibney2004; Torres and Ayala, Reference Torres and Ayala2010). It is expected that HRP-mimicking catalysts, such as heme b in micellar or vesicular systems, will depend on each of these factors. It remains to be investigated how these factors can be adjusted in an apoprotein-free system in vitro in order to obtain a heme b-based catalytic system of the desired redox potential, and catalytic performance.

In addition to the actual oxidation state of the iron ion in heme proteins, the iron's spin state is a characteristic property of iron porphyrins. In the case of ferric heme b, (PPIX)FeIII, with one or two axial ligands, three spin states are known for the five d electrons of Fe(III) (Scheidt and Reed, Reference Scheidt and Reed1981). They are the low-spin S = 1/2 state [(dxy)2 (dxz, dyz)3], the high-spin S = 5/2 state [(dxy)1 (dxz, dyz)2 (dz 2)2 (dx 2–y 2)0], and the intermediate-spin state. The intermediate-spin state is either a pure intermediate S = 3/2 state [(dxy)2 (dxz, dyz)2 (dz 2)1 (dx 2–y 2)0] or an admixed-intermediate S = 3/2, 5/2 state due to spin–orbit coupling, see Scheidt and Reed (Reference Scheidt and Reed1981) for details. The spin state in ferric heme b is determined by the axial ligands and the environment. The stronger the ligand field, the greater the d-orbital splitting and the more likely a low-spin state will be obtained (Scheidt and Reed, Reference Scheidt and Reed1981). This is independent of whether the heme is part of a heme protein or whether it is a synthetic heme complex. Strong axial ligands lead to low-spin hexacoordinated hemes, e.g. (PPIX)FeIII(Im,Im) (Scheidt and Reed, Reference Scheidt and Reed1981) or (PPIX)FeIII(pyr,pyr) (Ncokazi and Egan, Reference Ncokazi and Egan2005). Weaker axial ligands, typically anionic ones (e.g. chloride) lead to high-spin pentacoordinated hemes (Scheidt and Reed, Reference Scheidt and Reed1981). Since the main determinant of the spin state is the axial ligand field, there is a correlation between the spin state and the length of the bond between the iron ion and the N atoms coordinating to the iron (Nporphyrin). A short Fe–Nporphyrin bond means a strong bond, resulting in a low-spin state; a long Fe–Np orphyrin bond means a weak bond, resulting in a high-spin state, see the examples given by Scheidt and Reed (Reference Scheidt and Reed1981).

For gaining insight into the spin state of native, glycosylated (or recombinant, non-glycosylated) HRP, detailed resonance Raman spectroscopy measurements of solutions of recombinant HRP isoenzyme C (HRPC) dissolved in an aqueous buffer solution of pH ≈ 7 were carried out at T = 296 K (room temperature) and at T < 200 K (Smulevich et al., Reference Smulevich, English, Mantini and Marzocchi1991, Reference Smulevich, Paoli, Burke, Sanders, Thorneley and Smith1994, Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005). The measurements involved the analysis of the C=C stretching frequency of the two vinyl groups of PPIX after excitation in the Soret- or Q-band regions of the absorption spectrum. The overall conclusion from these measurements was that Fe(III) of the heme group of HRP at room temperature is a pentacoordinated mixed-spin state (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Maberge, Szigeti, Fidy and Schweitzer-Stenner2003; Smulevich et al., Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005). This state is, for example, characterized by an absorption spectrum similar to a pentacoordinated high-spin heme, but with shorter wavelength π → π* transitions at 630–635 nm due to the porphyrin to iron charge transfer transitions (Smulevich et al., Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005). According to Smulevich et al. (Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005), the spin state of HRP at pH ≈ 7 and room temperature ‘reflects a quantum mechanical admixture of intermediate (S = 3/2) and high (S = 5/2) spin states and is unusual in biological systems’. For an alkaline HRP solution (pH = 12), the absorption and resonance Raman spectra were characteristic of mainly hexacoordinated low-spin heme (due to the coordination of hydroxide ions to the iron and a strong H-bond between the axial hydroxide ligand and distal His42 and/or Arg38) (Feis et al., Reference Feis, Marzocchi, Paoli and Smulevich1994).

As a general conclusion drawn from the spin-state analysis of mutants of heme peroxidases, it seems that there is not necessarily a direct correlation (see Laberge et al., Reference Laberge, Szigeti and Fidy2004) between spin state and the catalytic activity of a heme enzyme; important is the role of the key amino acid residues involved in the catalytic cycle (including also the important amino acid side chains at the distal side of the heme group and the presence of an extensive network of H-bonds coupling the distal and proximal sides) (Smulevich et al., Reference Smulevich, Feis and Howes2005). The following section deals with the role of the amino acids at the heme's proximal and distal sides in HRP.

The importance of proximal His170 and distal His42 in HRP

One model to explain the role of proximal His170 and distal His42 and Arg38 in the first step of the catalytic peroxidase cycle of HRP is the ‘push–pull’ mechanism (Sono et al., Reference Sono, Roach, Coulter and Dawson1996; Shinomiya et al., Reference Shinomiya, Araki, Momotake, Kotani, Kojima and Yamamoto2019), see Fig. 9. A pair of electrons is donated from the imidazole group of His170 to the ferric iron ion of heme b. This ‘push’ effect seems to contribute to the stabilization of higher oxidation states of the iron ion during catalysis, most likely compound II (Ortmayer et al., Reference Ortmayer, Fisher, Basran, Wolde-Michael, Heyes, Levy, Lovelock, Anderson, Raven, Hay, Rigby and Green2020). On the other hand, during the catalytic cycle, distal His42 accepts a proton from the O-atom of Fe-bound H2O2 that is close to the iron ion and transfers it to the other O-atom of H2O2 after heterolytic cleavage of its peroxo bond to generate H2O, which then diffuses away (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, Arg38 facilitates the heterolytic –O–O– bond cleavage through stabilization of the developing negative charge of the distal O-atom during the bond cleavage. Thus, the ‘pull’ effect is provided by combined interactions involving His42 and Arg38. The experiments carried out by Ortmayer et al. (Reference Ortmayer, Fisher, Basran, Wolde-Michael, Heyes, Levy, Lovelock, Anderson, Raven, Hay, Rigby and Green2020) suggest that the ‘pull’ effect is related to an increased proton affinity of ferryl oxygen of compound II.

Fig. 9. ‘Push–pull mechanism’ to explain the role of proximal His170 and distal His42 and Arg38 in the formation of HRP compound I, as reported by Sono et al. (Reference Sono, Roach, Coulter and Dawson1996). The cleavage of the –O–O– bond in H2O2 positioned at the distal site occurs heterolytically. See also Shinomiya et al. (Reference Shinomiya, Araki, Momotake, Kotani, Kojima and Yamamoto2019) and Ortmayer et al. (Reference Ortmayer, Fisher, Basran, Wolde-Michael, Heyes, Levy, Lovelock, Anderson, Raven, Hay, Rigby and Green2020) and text for details. Reprinted with permission from Sono et al. (Reference Sono, Roach, Coulter and Dawson1996), Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

For the preparation of any type of artificial ‘HRP-mimicking’ systems, the ‘push–pull’ mechanism for the formation of the key intermediate compound I makes it clear that the local environment and coordination state of ferric heme b at the distal side is equally important as the situation at the proximal side. The key amino acids are proximal His170 (coordinating to the ferric iron) and distal His42 (not coordinating, but acting as acid/base catalyst), see Figs 4b and 7. Other amino acids nearby are also important (see e.g. Dunford, Reference Dunford2010). How well the local environment on the proximal and distal sides of heme b in HRP can be imitated with a HRP-mimicking system is the key question for any application of such systems that are based on a peroxidase-like catalytic activity.

To stress the importance of the environment in which ferric heme b is embedded in HRP, some of the results of the elegant experiments reported by Newmyer, Ortiz de Montellano, and collaborators in 1995 and 1996 are worth recalling (Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1995; Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). A mutant of HRPC lacking proximal His170, called H170A, was prepared and analyzed (Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). His170 (H170) was replaced with an alanine (A). The mutant contained an oligohistidine tag for easier purification, indicated as ‘hHRP’. The UV/vis absorption spectrum of H170A hHRP was measured (see Fig. 8b) and compared with native HRP (Fig. 8a) and hHRP. While the spectrum of native HRP and hHRP (recombinant HRPC with a His tag) did not change with pH, the spectrum of H170A hHRP showed a clear pH dependence, and the maximum of the Soret band at pH = 5–7 was shifted to higher wavelength (‘red-shifted’) by 9–11 nm if compared to hHRP. This indicated that Fe(III) was hexacoordinated, with two strongly binding axial ligands rather than a single one in native HRP (His170) (Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). The authors suggested that the two strongly binding axial ligands were His42 and H2O or HO−. In any case, blocking both coordination sites must result in low peroxidase activity since compound I cannot be formed efficiently according to the mechanism shown in Fig. 7c. The determined rate constant for the formation of compound I was in the case of H170A hHRP about 5 orders of magnitude lower than for native HRP or hHRP. Very low peroxidase activity of H170A hHRP was measured by using as reducing substrate either guaiacol (5 mM at pH = 6.0) or ABTS (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), 5 mM at pH = 5.0) in the presence of 0.5 mM H2O2 (see later Fig. 19 for the chemical structures of ABTS and guaiacol). H170A hHRP displayed only 0.003% of the guaiacol and 0.004% of the ABTS peroxidase activity of native HRP (Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). The rate of formation of compound I and the overall peroxidase activity of H170A hHRP could, however, be partially restored by adding saturating concentrations of imidazole (≈25 mM) to yield 0.8% (for guaiacol) and 0.5% (for ABTS) of the activity of native HRP (Newmyer et al., Reference Newmyer, Sun, Loehr and Ortiz de Montellano1996). This activity was still much lower than in the case of native HRP, but higher than the one of H170A without added imidazole.

In a second related work, Newmyer and Ortiz de Montellano prepared two mutants lacking distal His42, H42A hHRP and H42V hHRP (V = valine) (see Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1995). The determination of the peroxidase activity at pH = 7.0 and T = 25 °C with guaiacol (5.1 mM) as a reducing substrate and H2O2 (0.5 mM) showed that the initial rates of guaiacol oxidation was ≈104 fold lower than in the case of native HRP of hHRP; the rate of formation of compound I was even ≈106 fold lower for the mutants as compared to native HRP or hHRP (Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1995). This clearly demonstrated the importance of His42 for efficient compound I formation and for efficient guaiacol oxidation. Trials to increase the peroxidase activity of the mutant H42A hHRP by adding imidazole showed only a modest increase that leveled off with increasing imidazole concentration, indicating the formation of inactive hexacoordinated heme b (Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1996). With 2-methylimidazole or 1,2-dimethylimidazole (for the chemical structures, see later Fig. 18), the situation was much better because coordination to Fe(III) was not possible, the added deprotonated form of 2-methylimidazole or 1,2-dimethylimidazole acting as an acid/base catalyst (Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1996). The partial ‘rescue’ of the peroxidase activity of H42A hHRP by added 1,2-dimethylimidazole was demonstrated by using guaiacol or ABTS as reducing substrates; the native HRP or hHRP still being 10–100 times more active than the mutant with added 1,2-diimidazole (see Newmyer and de Montellano, Reference Newmyer and de Montellano1996).

In another investigation of a HRPC mutant lacking distal His42, H42L hHRP (L = leucine), evidence was presented that the peroxo bond in H2O2 is cleaved homolytically and not heterolytically, resulting in the formation of hydroxy radials (HO•) and compound II (Rodríguez-López et al., Reference Rodríguez-López, Lowe, Hernández-Ruiz, Hiner, García-Cánovas and Thorneley2001). Instead of compound I, another intermediate might form with a oxoferryl moiety and a protein radical, (por)FeIV(O) R•, called compound I*, instead of a porphyrin radical cation (por+•)FeIV(O) (Fig. 7) (see Rodríguez-López et al., Reference Rodríguez-López, Lowe, Hernández-Ruiz, Hiner, García-Cánovas and Thorneley2001).

Overall, the primary and secondary structures of the apoproteins in heme b proteins determine the local environment of heme b and thus its chemical properties. The second, third, and fifth factors mentioned above are thus interdependent and as such determined by the apoprotein structure, which is the outcome of million years of biological evolution. Therefore, it is not surprising that it is difficult to replace a sophisticated proteinaceous heme b environment by non-natural apoprotein mimics for achieving a similar catalytic performance of heme b as in the case of native heme b proteins under their respective physiologically optimal conditions.

Concerning the use of heme b in a functional state in a non-natural environment, such as surfactant micelles or artificial vesicle membranes, for potential synthetic or analytical applications, the challenge is to find conditions that mimic to some extent one of the many situations of active (monomeric) heme b embedded in a protein environment. Depending on the biological activity of heme b one is interested in, finding such conditions might be very demanding. One of the activities that raised the most interest to mimic with heme b-based non-natural systems is the peroxidase activity of HRP or other heme peroxidases, see Fig. 7a. As outline below, many approaches have been undertaken already, not only by using micelles or vesicles for providing the hydrophobic environment of ferric heme b at the active site of HRP (see later Fig. 15). Before summarizing some of these approaches, two physico-chemical properties of free ferric heme b are important to mention: (i) the aggregation state in aqueous media and in organic solvents, and (ii) the spectroscopic properties in the UV and vis regions of the absorption spectrum. Some of the key findings concerning both properties are summarized in the next section.

Two of the physico-chemical properties of ferric heme b

Aggregate formation

Among the different physico-chemical properties of ferric heme b (= hemin), its propensity to form aggregates in aqueous solution is arguably the most important one. One of the first reports on the hemin insolubility in water dates back to the 1940s (Morrison and Williams, Reference Morrison and Williams1941). A couple of decades later, it was found that the peculiarity of hemin is not its insolubility in water but rather the existence of multiple structurally different aggregation states: monomeric hemin, π–π dimer, μ-oxo dimer, or large stacks (also called π–π stacks) of μ-oxo dimers (de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007; Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009; de Villiers and Egan, Reference de Villiers and Egan2014), see Fig. 10. Depending on the exact experimental conditions, one of the four aggregation states will be predominant. Each aggregation state has its characteristic physico-chemical properties. Out of the four aggregation states shown in Fig. 10, only monomeric hemin can be catalytically active (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Dean and Jones1970; Kremer, Reference Kremer1973), while aggregated hemin exhibits negligible catalytic activity. This was, for example, demonstrated with the seminal experiments of Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Dean and Jones1970) in which the decomposition of H2O2 in the presence of hemin under different conditions was measured, so-called ‘catalatic activity’. The key conclusion from these experiments is also important for those interested in preparing HRP mimics based on free hemin: experimental conditions must be applied under which hemin is monomeric. Therefore, the main challenges are: (i) knowing which experimental parameters affect the aggregation state of hemin, and (ii) knowing how to adjust these parameters to obtain predominantly monomeric hemin. In the following, we will first explain the features of each of the four aggregation states of hemin. Second, we will summarize literature data that correlate experimental conditions with the dominating aggregation state of hemin, with particular emphasis on conditions under which monomeric hemin prevails. Third, characteristic UV/vis spectroscopic features of each aggregation state will be covered.

Fig. 10. Depiction of the equilibria between four different hemin aggregation states in aqueous solution, as reported by Asher et al. (Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009) and de Villiers and Egan (Reference de Villiers and Egan2014): monomer, π–π dimer, μ-oxo dimer, and large aggregates of μ-oxo dimers. Note that the scheme refers to situations at pH = 10, i.e. with fully ionized propionic acid groups. The situation gets more complicated if the pH value is below the pK a values of the two carboxylic acid groups (pK a1 = 4.3, pK a2 = 5.6–6.4, see Durrant (Reference Durrant2014) and the legend of Fig. 2). In addition, with a decrease in pH, the ligands coordinating at the 5th and 6th coordination sites change from the hydroxyl group (−OH) to water (H2O) (see Crespo et al., Reference Crespo, Tilley and Klonis2010). Adapted with permission from Asher et al. (Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009), Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

Monomeric hemin, as the name implies, is in a non-aggregated state, resembling ferric heme b in the resting state of many contemporary heme enzymes, such as HRP (see Berglund et al., Reference Berglund, Carlsson, Smith, Szöke, Henriksen and Hajdu2002; Dunford, Reference Dunford2010; Poulos, Reference Poulos2014; Huang and Groves, Reference Huang and Groves2018). The two types of dimers, π–π and μ-oxo, differ in the way of interaction between two hemin molecules. In the case of the π–π dimer, there is π–π interaction between two hemin molecules, while in the case of the μ-oxo dimer, an oxygen atom bridges two hemin molecules via their iron atoms. In both types of dimers, the carboxylic acid/carboxylate moiety are pointing in opposite directions, see Fig. 10. In the past, it was initially thought that only μ-oxo dimers exist. However, later on it was clearly shown that under certain conditions π–π dimers can also form (de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007; Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009). Large aggregates of μ-oxo dimers form when μ-oxo dimers stack via the non-coordinated sides of the porphyrins by π–π interactions.

In addition to the π–π and μ-oxo dimers mentioned so far (Fig. 10), a third hemin dimer type is known, a μ-propionato dimer, see Fig. 11. A biocrystalline material called ‘hemozoin’ (malaria pigment) and comprising this dimer type exists inside the digestive vacuole of Plasmodium falciparum (pH ≈ 4.5–4.8) (Ketchum et al., Reference Ketchum, Olafson, Petrova, Rimer and Vekilov2013; de Villiers and Egan, Reference de Villiers and Egan2014) and other blood-feeding parasites, after the parasite has invaded red blood cells (erythrocytes in humans). The parasite causes the release of ferrous heme b, (PPIX)FeII, from the erythrocytes' Hb. Upon rapid oxidation to ferric heme b, (PPIX)FeIII, crystallization in a lipidic environment (vacuole membrane or intravacuolar lipid bodies) occurs. In vitro experiments have shown that a lipidic environment promotes such crystallization, and the synthetic material is referred to as β-hematin (and in some cases, hematin anhydride) (see Egan et al., Reference Egan, Chen, de Villiers, Mabotha, Naidoo, Ncokazi, Langford, McNaughton, Pandiancherri and Wood2006; Egan, Reference Egan2008; Orjih et al., Reference Orjih, Mathew and Cherian2012; Huy et al., Reference Huy, Shima, Maeda, Men, Hirayama, Hirase, Miyazawa and Kamei2013; Ketchum et al., Reference Ketchum, Olafson, Petrova, Rimer and Vekilov2013; Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Nadovich and Spadafora2014; de Villiers and Egan, Reference de Villiers and Egan2014; Vekilov et al., Reference Vekilov, Rimer, Olafson and Ketchum2015; Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Mohunlal, Fitzroy, Asher, Smith, Egan and De Villiers2016). This crystallization appears to be a ‘strategy’ of the parasite to prevent its own destruction, which would occur if dissolved (PPIX)FeIII would interact with the plasma membrane of the parasite, thereby causing membrane lysis (Fitch et al., Reference Fitch, Chevli, Kanjananggulpan, Dutta, Chevli and Chou1983).

Fig. 11. (a) Two unit cells of the crystal structure of β-hematin (= hemozoin), as determined by Pagola et al. (Reference Pagola, Stephens, Bohle, Kosar and Madsen2000). The crystal consists of cyclic μ-propionato dimers that are stabilized by two Fe–O coordination bonds (Fe1–O41), while two dimers are linked by hydrogen bonds (through O36 and O37), as reported by Pagola et al. (Reference Pagola, Stephens, Bohle, Kosar and Madsen2000). (b) Depiction of one cyclic μ-propionato dimer and the linking hydrogen bonds, as reported by Rifaie-Graham et al. (Reference Rifaie-Graham, Pollard, Raccio, Balog, Rusch, Hernández-Castañeda, Mantel, Beck and Bruns2019) (see also Gildenhuys et al., Reference Gildenhuys, Roex, Egan and De Villiers2013; de Villiers and Egan, Reference de Villiers and Egan2014; Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Mohunlal, Fitzroy, Asher, Smith, Egan and De Villiers2016). Reproduced with permission from (a) Pagola et al. (Reference Pagola, Stephens, Bohle, Kosar and Madsen2000), Springer Nature and (b) Rifaie-Graham et al. (Reference Rifaie-Graham, Pollard, Raccio, Balog, Rusch, Hernández-Castañeda, Mantel, Beck and Bruns2019), Springer Nature.

Overall, the aggregation behavior of (PPIX)FeIII is rather complex. The aggregation state is affected by multiple factors: solvent type, pH, buffer salt, and neutral salt (e.g. NaCl) if added (type and concentration), the concentration of hemin itself, and the presence of ‘additives’ that alter the solvent properties, e.g. micelle forming amphiphiles. The challenge is to know how to set the conditions to obtain a desired aggregation state that will be present predominantly. In Table 2, a few chosen examples of conditions are listed to depict how the experimental conditions determine the state of hemin.

Table 2. Examples of the predominant aggregation state of (PPIX)FeIII depending on the experimental conditions

CHES, 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethane-1-sulfonic acid; HEPES, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid.

Hemin dissolved in pure DMSO, up to concentrations of at least a few millimolars, is in monomeric state (Table 2, entry 1) (Brown and Lantzke, Reference Brown and Lantzke1969), while in aqueous solution at pH 6–9 (de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007; Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Streltsov, Davydova, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2014) or at pH = 10 (Table 2, entry 2), hemin forms π–π dimers (Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009) (Table 2, entry 2). In a detailed spectrophotometric study, de Villiers et al. (Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007) determined the dimerization constant for pH 6–9 conditions (at an ionic strength of 0.154 M), yielding K D,obs ≈ 3.2 × 106 M−1 (K D = [dimer]/[monomer]2). No big variation of this constant with pH was found; above 10 μM (PPIX)FeIII, more than 92% dimerized (see de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007).

Another important experimental finding of de Villiers et al. (Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007) was the strong tendency of (PPIX)FeIII to adsorb from aqueous solution onto the surface of the glass or plastic vessels used for the experiments. This property must be taken into account in experiments with hemin in aqueous solution to avoid misinterpretation of experimental observations.

From a practical point of view, to minimize effects that might arise from surface adsorption of hemin added to an aqueous solution, the suggestion is to freshly prepare a concentrated hemin stock solution in DMSO and then add a small portion of it to an aqueous solution that contains molecules – or molecular assemblies – that can act as ‘hosts’ to bind hemin by providing a suitable local environment (Cvjetan et al., Reference Cvjetan, Kissner, Bajuk-Bogdanović, Ćirić-Marjanović and Walde2022). Some of the most common hosts which were employed for this purpose are: G-quadruplex RNAs or DNAs, human serum albumin (HSA) and other proteins, or sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) or sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS) micelles, see below. The small percentage of DMSO present in the final solution (typically about 1% (v/v)) should not lead to any undesired alterations of the system.

In water/organic solvent mixtures (Table 2, entries 3 and 4), at constant concentration of the organic solvent, the physical state of hemin depends on whether the organic solvent used is protic or aprotic. Protic solvents (e.g. MeOH) induce the formation of π–π dimers, while aprotic solvents (e.g. DMSO) induce μ-oxo dimer formation (Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009). The explanation offered is that the number of solvent molecules that are stabilizing a water molecule bound to Fe(III) (at axial position) via hydrogen bonds is of outmost importance. In the case of protic solvents, the maximum number of solvent molecules that can interact through a hydrogen bond with a water molecule bound to Fe(III) is 3, while in the case of aprotic solvents, it is 2. Further examples of water/organic solvent mixtures using organic solvents different from the ones mentioned here can be found in Asher et al. (Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009). Interestingly, by exchanging the organic solvent, π–π dimers can convert into μ-oxo dimers, and vice versa (Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009). In pure aqueous solutions, at high salt concentrations (Table 2, entry 5), hemin is preferentially present in the form of large stacks of μ-oxo dimers. If an aqueous solution contains surfactants, they influence the aggregation state of hemin (Table 2, entry 6–8). Depending on the chemical structure of the surfactant and its concentration, hemin can be present in monomeric form, if SDS and SDBS surfactants are used, or as μ-oxo dimers if for example Tween-20 is present (Casabianca et al., Reference Casabianca, Kallgren, Natarajan, Alumasa, Roepe, Wolf and de Dios2009). The use of micelle- or vesicle-forming amphiphiles for keeping hemin in monomeric, catalytically active state in aqueous solution will be discussed in detail in the next section.

UV/vis absorption characteristics

Information about the aggregation state of dissolved, dispersed, or solubilized hemin can be obtained by a number of complementary analytical methods: most importantly UV/vis spectroscopy (de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007; Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009; Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2012; Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Kronenberg and Fry2017), Raman spectroscopy (Boffi et al., Reference Boffi, Das, della Longa, Spagnuolo and Rousseau1999; Shantha et al., Reference Shantha, Saini, Thanga and Verma2003), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Mazumdar, Reference Mazumdar1990; Casabianca et al., Reference Casabianca, Kallgren, Natarajan, Alumasa, Roepe, Wolf and de Dios2009), cyclic voltammetry (Toader and Volanschi, Reference Toader and Volanschi2007; Moosavi-Movahedi et al., Reference Moosavi-Movahedi, Semsarha, Heli, Nazari, Ghourchian, Hong, Hakimelahi, Saboury and Sefidbakht2008), X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy (Boffi et al., Reference Boffi, Das, della Longa, Spagnuolo and Rousseau1999), extended X-ray absorption spectroscopy (Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Streltsov, Davydova, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2014), magnetic circular dichroism (Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2012), and molecular dynamics simulation (Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Streltsov, Davydova, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2014, Reference Kuter, Mohunlal, Fitzroy, Asher, Smith, Egan and De Villiers2016). Although the UV/vis absorption spectrum of (PPIX)FeIII in heme proteins (see Fig. 8) or of free hemin in different media is quite complex, recording the UV/vis absorption spectrum turned out to be useful as an analytical tool to gain insight into the aggregation state of hemin and its local environment (including axial ligand coordination and the formation of compound I in the case of HRP, with a radical cation localized on the porphyrin ring, see Fig. 8a). A brief overview about some of the characteristic features of the UV/vis absorption spectrum of hemin is given in the following.

As shown in Fig. 1b, porphyrins (and metalloporphyrins) have 22 π electrons, of which 18 are delocalized (planar aromatic compound following Hückel's rule, 4n + 2 π electrons, with n = 4, n being a non-negative integer). In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gouterman successfully explained the origin of the UV/vis bands of porphyrins using a simple ‘four-orbital model’ (Gouterman, Reference Gouterman1959, Reference Gouterman1961, Reference Gouterman1978; Gouterman et al., Reference Gouterman, Wagnière and Snyder1963). According to this model, the two highest occupied molecular orbitals, HOMOs, of a typical porphyrin are near degenerate, as are the two lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals, LUMOs, and these four MOs are well separated from all other occupied and unoccupied MOs, see Fig. 12a (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kwan and Stillman2017). The basic features of the electronic spectra of porphyrins are then explained, to a first approximation, as π → π* transitions involving these four orbitals (Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2000). Depending on the type of porphyrin, the central metal ion in metalloporphyrins like (PPIX)FeIII (Dunford, Reference Dunford2010), the axial ligands, and the environment, the near degenerate pair of HOMO and LUMO become different in energy and vibrational states, resulting in a characteristic general pattern of the absorption spectrum of most metalloporphyrins (Wang and Hoffman, Reference Wang and Hoffman1984), also involving transitions between the HOMOs and vacant d-orbitals of the central metal ion (Dunford, Reference Dunford2010). An extremely strong band, the Soret band (also called B-band) is present between 380 and 500 nm (ɛ ≈ 105 M−1 cm−1) and much weaker Q-bands exist between 500 and 750 nm (ɛ ≈ 104 M−1 cm−1) (Wang and Hoffman, Reference Wang and Hoffman1984), see also Fig. 8. The two calculated HOMOs, HOMO and HOMO − 1, are a1u and a2u (both of them are π orbitals), while the two LUMOs, LUMO and LUMO + 1, are egx and egy (both of them are π* orbitals), see Fig. 12a. Transition of electrons between the HOMOs and LUMOs gives rise to the characteristic spectrum. Both band types arise from π → π* transitions, with the difference that the Soret band arises from S0 → S2 (singlet ground state to second excited single state), while Q-bands arise from S0 → S1 (singlet ground state to first excited single state) transitions, see Fig. 12b (Giovannetti, Reference Giovannetti and Uddin2012). Four clear transitions in the Q-band region can be identified in metal-free porphyrins, while complexation with a metal ion results in two transitions only (Milgrom, Reference Milgrom1997; Giovannetti, Reference Giovannetti and Uddin2012).

Fig. 12. Illustrations of Gouterman's ‘four orbital model’ for explaining the key electron transitions that determine the absorption spectrum of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins (aromatic 18 π-electron system). The four orbitals to consider are the two HOMOs and the two LUMOs. (a) Schematic drawing of the two relevant HOMOs and the two relevant LUMOs in porphyrins, shown for metalloporphyrin, as reported by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Kwan and Stillman2017). (b) Qualitative molecular orbital diagram for the allowed transitions involving the Fe(III) and porphyrin orbitals for hemin, considering different energy levels of the two HOMOs and high spin state of Fe(III), as reported by Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Langford, Cooke, Lim, Glenister, Duriska, Unthank and Mcnaughton2004). The measured UV/vis absorption spectra of (PPIX)FeIII in different environments and with different axial ligands can be understood – at least qualitatively – on the basis of dominating transitions between the two HOMOs and LUMOs of the porphyrin and minor contributions from transitions between the porphyrin MOs and the d-orbitals of Fe(III) (see also Kuter et al., Reference Kuter, Venter, Naidoo and Egan2012). (a) Reprinted with permission from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Kwan and Stillman2017). (b) Reprinted with permission from Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Langford, Cooke, Lim, Glenister, Duriska, Unthank and Mcnaughton2004), Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society.

In many cases, the absorption is determined by π → π* transitions of the porphyrin. This is clearly evident from a comparison of the UV/vis absorption spectrum of native HRP and compound I (Fig. 8a). On the other hand, ligand binding at the axial positions of heme b can also have a big effect on the spectrum, both in the Soret and the Q-band regions (see Fig. 8b and later Figs 18 and 23).

Regardless of a complete theoretical description and understanding of the complex absorption spectra of metalloporphyrins, the UV/vis absorption spectrum of hemin depends on its aggregation state, as it reflects the situation at the axial coordination sites and the local environment of hemin. In Fig. 13, UV/vis absorption spectra of monomeric hemin (a), π–π dimer (b), μ-oxo dimer (c), and large stacks of μ-oxo dimers (d) are shown, see also Table 2.

Fig. 13. UV/vis absorption spectra of hemin in different aggregation states, as reported by Brown and Lantzke (Reference Brown and Lantzke1969; spectrum a) or Asher et al. (Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009; spectra b–d). (a) Monomeric heme (determined on the basis of the analysis of DMSO solutions containing between 8 and 400 μM hemin; molar absorption coefficient, ɛ, given in M−1 cm−1); (b) π–π dimer (30 μM in aqueous solution, pH = 10); (c) μ-oxo dimer (30 μM in 5.64 M aqueous DMSO (= 40 vol%)); and (d) large stacks of μ-oxo dimers (30 μM in 4.25 M NaCl at pH = 10). For the absorbance versus wavelength plots in (b–d), the aqueous solutions were buffered with 20 mM CHES (N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid). (a) Reprinted with permission from Brown and Lantzke (Reference Brown and Lantzke1969). (b–d) Reprinted with permission from Asher et al. (Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009), Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

In Fig. 13a, the UV/vis spectrum of hemin dissolved in DMSO is shown, as reported by Brown and Lantzke (Reference Brown and Lantzke1969). In this case, hemin is predominantly present in monomeric form. The Soret band is narrow, positioned at around 400 nm with a molar absorption coefficient (also called extinction coefficient) of ɛ 405 = 183 000 M−1 cm−1 (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Pratt, De Wet and Tshabalala1979). In the Q-band region, there are two distinct bands positioned at ≈500 and ≈630 nm with significantly lower molar absorption coefficients. If dissolved in 0.01 N NaOH, the molar absorption coefficient of hemin was found to be much lower than in DMSO, ɛ 383 = 62 000 M−1 cm−1 (Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Sahal and Chauhan2002), while in water (pH = 7.2, at ionic strength of 0.154 M) a value of ɛ 393 = 79 000 M−1 cm−1 was determined. The UV/vis absorption spectra of π–π or μ-oxo dimers, Figs 13b and c, respectively, are significantly different from the spectrum of monomeric hemin. In the Soret band region, the absorption peak is much broader than in the case of monomeric hemin, and the molar absorption coefficient is approximately half that of the hemin monomer, i.e. around ɛ 393 = 45 000 M−1 cm−1 for the π–π dimer at pH = 7.2, 0.154 M ionic strength (de Villiers et al., Reference de Villiers, Kaschula, Egan and Marques2007). A further difference can be seen in the Q-band region, with regard to the position of the bands. It is especially interesting that based on the position and presence/absence of the Q-bands, it is possible to distinguish between π–π and μ-oxo dimers. The π–π dimer has a band positioned at 605 nm, while the μ-oxo dimer has a band at 575 nm with a shoulder at 600 nm (Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009). Lastly, the UV/vis spectrum of large aggregates of μ-oxo dimers is recognizable by a broad Soret band with a molar absorption coefficient even lower than that of the dimers. The Q-bands are similar to the ones of the μ-oxo dimer (Asher et al., Reference Asher, de Villiers and Egan2009).