Introduction

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) introduced “somatic symptom disorder” (SSD) as a new diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM-5 diagnosis not only received a new name; its diagnostic criteria also differ radically from somatization disorder which it replaced: Following scientific evidence of over two decades (Kroenke, Reference Kroenke2003; Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012), positive psychological criteria were formulated, i.e. excessive health concerns, and exclusion of potentially underlying medical disorders was no longer required. There are three diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013): The A-criterion requires one or more distressing or disabling somatic symptoms. The B-criterion requires disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness of one's symptoms (cognitive dimension), high levels of anxiety about health or symptoms (affective dimension), or excessive energy or time devoted to these symptoms or health concerns (behavioral dimension). The C-criterion specifies that somatic symptoms should persist for over 6 months. SSD also replaced DSM-IV's undifferentiated somatoform disorder, hypochondriasis, and the pain disorders. SSD specifiers with regard to severity, pain, and persistence were introduced (Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013). Patients with severe health anxiety and somatic symptoms are now assigned to SSD and those with solely health anxiety without somatic symptoms to “illness anxiety disorder” (IAD).

DSM-5 explicitly allows SSD to be diagnosed in addition to any comorbid somatic disease, thus avoiding both mind−body dualism and equating medically unexplained with psychogenic. The new criteria also meant to reduce stigmatization: Earlier diagnostic concepts of somatoform disorders in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 1992) described affected patients as “difficult,” unable to accept that symptoms are not caused by pathophysiology, and repeatedly requesting medical examinations. After publication, SSD criteria were criticized as imprecise (Mayou, Reference Mayou2014) and overinclusive, risking overdiagnosis (Frances, Reference Frances2013). In the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2021), which will take effect in January 2022, the former category of somatoform disorders has also been intensively revised and designated with the term “bodily distress disorder” (BDD). BDD is in large parts similar to SSD; in this respect, it is to be expected that some strengths and weaknesses of SSD will also apply to BDD, for which empirical studies are still missing.

A decade of research on the new SSD diagnosis is now available since the start of the scientific discussion that led to the release of DSM-5. From 2019 to 2021, the APA prepared a text revision of the DSM-5, to which authors of this article contributed as a section editor (JL) and reviser (BL). The literature review for DSM-5-TR was expanded into this scoping review. Its primary aim was to summarize the evidence on the diagnostic criteria of SSD, following the topics addressed in the text sections of the SSD chapter of DSM-5. The second aim was to identify the most relevant research gaps regarding SSD.

Methods

Search strategy

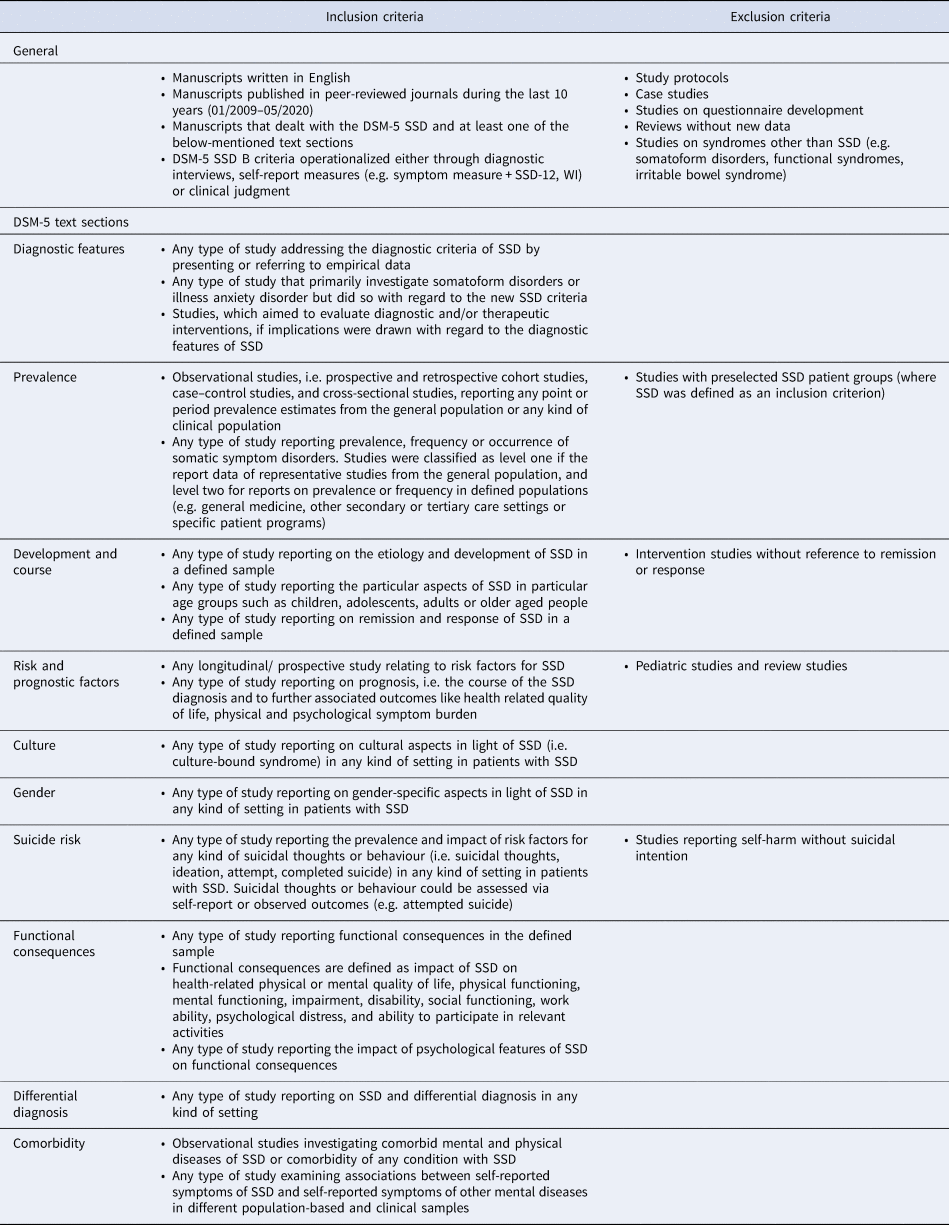

A review protocol defining the databases and search terms was drafted by the research team and refined by a research librarian (online Supplemental material). We defined outcome domains based on the subheadings for the specific DSM-5 text sections, i.e. diagnostic features, prevalence, development and course, risk and prognostic factors, culture-related diagnostic issues, gender-related diagnostic issues, suicide risk, functional consequences of SSD, differential diagnosis and comorbidity. Table 1 summarizes general inclusion and exclusion criteria and those specific for each text section. To identify all potentially relevant studies, the bibliographic databases PubMED, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library for systematic reviews were accessed. Searches were conducted between January and May 2020.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature search within each DSM-5 SSD text section

Note. SSD, Somatic symptom disorder; SSD-12, Somatic Symptom Disorder B-criteria Scale; WI, Whitley Index.

Study selection and data extraction

All identified records were collected in Endnotex9 where duplicates were removed. All titles and abstracts were screened for their relevance to the DSM-5 text sections, research questions and eligibility criteria. Selected articles were evaluated based on full text and reviewed by at least two researchers. Disagreements regarding inclusion were discussed and a consensus was resolved through team discussions. Reviewers also checked reference lists of studies meeting inclusion criteria, relevant review articles and editorials to identify further relevant studies. For each DSM-5 text section on SSD, searches were conducted separately, and the number of identified studies was documented. Subsequently, key information within each DSM-5 text section was extracted into a standard data form including publication year, study population, study design, SSD assessment and DSM-5 text section. Review findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun, Levac and Straus2018).

Results

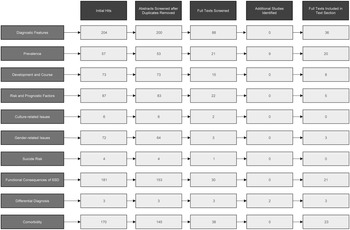

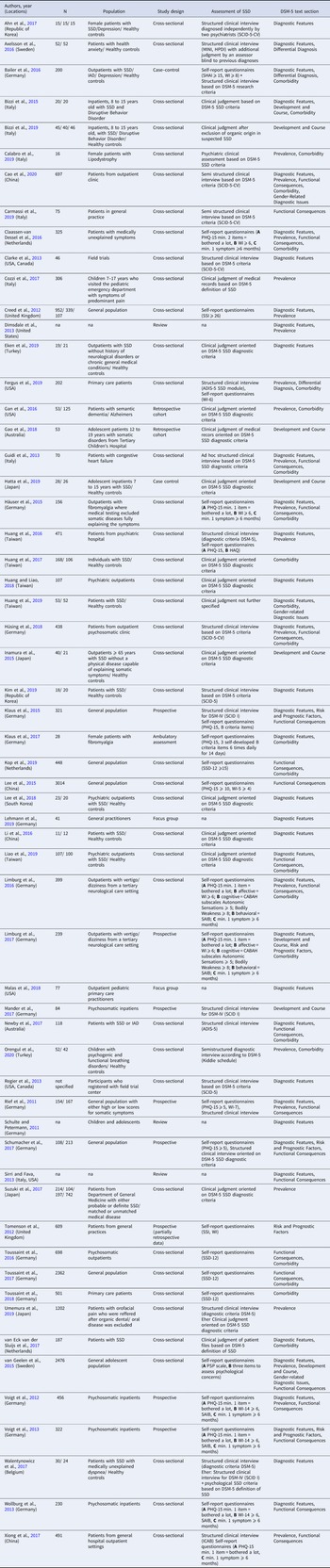

The literature search identified 882 articles. After duplicates were removed, 781 abstracts were screened for eligibility. After the screening of abstracts and including additional studies identified in the reference lists, full texts were screened in 250 studies. Several studies were identified for multiple DSM-5 text sections, and after full-text screening and excluding duplicate articles that were identified for multiple text sections eventually 59 articles were included into the analyses (see Fig. 1 for flow chart). Table 2 provides an overview of the included full texts with study design, sample size and operationalization of SSD criteria.

Fig. 1. Study flow chart for scoping review. Displayed are the number of articles per DSM-5 text section. Some articles were identified for multiple text sections, thus the total number of articles included does not equal the column total (e.g. full texts included: column total, n = 119; total number of included articles, n = 59).

Table 2. Overview of included studies

Note. ADIS-5, Anxiety Disorders Interview for DSM-5; HAQ, Health Anxiety Questionnaire; HPDI, Health Preoccupation Diagnostic Interview; IAD, Illness Anxiety Disorder; ICAB, Interview about cognitive, affective, and behavioral features associated with somatic complaints; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 6; PHQ-15, Patient Health Questionnaire 15; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PSP scale, Psychosomatic Problems Scale; SAIB, Scale for the Assessment of Illness Behavior; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for Disorders according to DSM-5; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist; SSD, Somatic Symptom Disorder; SSD-12, Somatic Symptom Disorder B-criteria Scale; SHAI, Short Health Anxiety Inventory; SSI, Somatic Symptom Inventory; WI, Whitley Index;

Diagnostic features

Reliability of the SSD criteria

In the DSM-5 field trials (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Narrow, Regier, Kuramoto, Kupfer, Kuhl and Kraemer2013), SSD showed good inter-rater reliability between clinicians of intra-class κ = 0.61 (Regier et al., Reference Regier, Narrow, Clarke, Kraemer, Kuramoto, Kuhl and Kupfer2013), which compared favorably with other psychiatric disorders (Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013). One study indicated that SSD and IAD were more reliable diagnoses than the DSM-IV diagnosis of hypochondriasis (Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong, & Andrews, Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017). Another study indicated by an overall interrater agreement of Cohen's κ = 0.85 that clinicians could distinguish well between healthy controls and patients with SSD or IAD (Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn, & Hedman, Reference Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn and Hedman2016). Agreement between raters was, however, much lower regarding severity, pain and persistence specifiers of SSD.

Validity of the SSD criteria

Studies in psychosomatic clinics showed a higher frequency for DSM-5 SSD compared to DSM-IV somatoform disorders (Hüsing, Löwe, & Toussaint, Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018; Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012). However, mental impairment at discharge was greater for SSD compared to DSM-IV somatoform disorders (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012). A study in patients with medically unexplained symptoms also indicated more severe physical symptoms and impairment in patients with SSD compared to DSM-IV somatoform disorder (Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker, & van der Horst, Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016). In contrast, in patients with dizziness and vertigo, lower impairment for patients with SSD compared to patients with DSM-IV somatoform disorders was observed (Limburg, Sattel, Radziej, & Lahmann, Reference Limburg, Sattel, Radziej and Lahmann2016). Rief and colleagues (Rief, Mewes, Martin, Glaesmer, & Braehler, Reference Rief, Mewes, Martin, Glaesmer and Braehler2011) concluded in their early evaluation of SSD that the SSD criteria themselves are not over-inclusive.

The majority of studies considered the inclusion of the B-criteria as a positive change in the diagnostic conception (Claassen-van Dessel et al., 2016; Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Rief, Brähler, Martin, Glaesmer and Mewes2015; Wollburg, Voigt, Braukhaus, Herzog, & Löwe, Reference Wollburg, Voigt, Braukhaus, Herzog and Löwe2013). However, the choice of the three psychological B-criteria was criticized (Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Rief, Brähler, Martin, Glaesmer and Mewes2015), and the relevance of the clinical context and the interpretation of these criteria were highlighted for diagnosing SSD and its severity (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020; Huang, Chen, Chang, & Liao, Reference Huang, Chen, Chang and Liao2016). Two studies compared SSD and IAD, indicating higher health service use, more comorbid anxiety disorders (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Kerstner, Witthoeft, Diener, Mier and Rist2016; Newby et al., Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017), more severe health anxiety, depression and somatic symptoms in individuals with SSD compared to individuals with IAD (Newby et al., Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017).

With regard to SSD in early life, SSD criteria were seen as helpful (van Geelen, Rydelius, & Hagquist, Reference van Geelen, Rydelius and Hagquist2015) and more suitable for children and adolescents compared to prior diagnoses (Schulte & Petermann, Reference Schulte and Petermann2011). Other authors suggested that an insecure and disorganized attachment style toward parents might be associated with adolescent SSD (Bizzi, Cavanna, Castellano, & Pace, Reference Bizzi, Cavanna, Castellano and Pace2015).

A general population study indicated that the total number of somatic symptoms in the general population was an independent predictor for health status (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Davies, Jackson, Littlewood, Chew-Graham, Tomenson and McBeth2012). The authors concluded that these findings supported abandoning the diagnostic criterion that somatic complaints must be medically unexplained, as was required with somatoform disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10. The predictive validity of SSD's diagnostic criteria was further demonstrated in psychosomatic inpatients (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2013) and in patients with fibromyalgia (Klaus, Fischer, Doerr, Nater, & Mewes, Reference Klaus, Fischer, Doerr, Nater and Mewes2017). Further, psychological distress was more strongly associated with patient complexity than the number of physical symptoms (van Eck van der Sluijs, de Vroege, van Manen, Rijnders, & van der Feltz-Cornelis, Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, de Vroege, van Manen, Rijnders and van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). Another study indicated that patients with SSD showed a lower level of functioning and quality of life than healthy controls (Liao, Ma, Lin, & Huang, Reference Liao, Ma, Lin and Huang2019). Comparing SSD to other diagnoses with regard to future healthcare utilization, SSD was found to be a valid, yet not a superior diagnosis (Schumacher, Rief, Klaus, Brähler, & Mewes, Reference Schumacher, Rief, Klaus, Brähler and Mewes2017). Note, however, that most of the studies mentioned had used proxy SSD criteria, otherwise specified “clinical judgment,” or previous diagnostic concepts for diagnosis. The diagnostic approaches used in each study are specified in Table 2.

Clinical utility of the new criteria

According to the DSM-5 field trials, SSD was among the most improved and useful criteria sets according to clinicians (Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013; Regier et al., Reference Regier, Narrow, Clarke, Kraemer, Kuramoto, Kuhl and Kupfer2013). Other authors stressed the clinical utility of the new concept compared to DSM-IV (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012). Results from a qualitative study in general practitioners indicated that the advantages of SSD outweigh its disadvantages; especially the new psychological criteria and no longer making the diagnosis by exclusion of physical disease were regarded as improvements for clinical practice (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Jonas, Pohontsch, Zimmermann, Scherer and Löwe2019). In a study of pediatric primary care providers' experiences with patients with SSD, inexperience in applying the diagnostic criteria became apparent despite clinicians' postulated interest (Malas, Donohue, Cook, Leber, & Kullgren, Reference Malas, Donohue, Cook, Leber and Kullgren2018). In patients with fibromyalgia, clinical utility of SSD was judged to be limited (Häuser, Bialas, Welsch, & Wolfe, Reference Häuser, Bialas, Welsch and Wolfe2015). Two studies suggested using “diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research” to improve DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (Huang & Liao, Reference Huang and Liao2018; Sirri & Fava, Reference Sirri and Fava2013).

Associated features

Some potential additional features of SSD have been investigated, e.g., body scanning, illness denial, and self-concept of bodily weakness (Guidi, Rafanelli, Roncuzzi, Sirri, & Fava, Reference Guidi, Rafanelli, Roncuzzi, Sirri and Fava2013; Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Rief, Brähler, Martin, Glaesmer and Mewes2015; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Voigt, Braukhaus, Herzog and Löwe2013). Other studies, all including small samples, suggested potential cerebral changes in patients with SSD, e,g. in the right temporal and the left inferior parietal gyri (Eken et al., Reference Eken, Colak, Bal, Kusman, Kizilpinar, Akaslan and Baskak2019), frontostriatal circuit dysfunction (Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Han, Hong, Min, Lee, Hahm and Kim2017), changes in regional homogeneity values (Li et al., Reference Li, Xiao, Li, Li, Lu, Xu and Yuan2016), altered autonomic reactivity (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liao, Tu, Yang, Kuo and Gau2019; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim, Cheon, Hwang, Jung and Kang2018), altered pain processing (Kim, Hong, Min, & Han, Reference Kim, Hong, Min and Han2019), and changes in autobiographical memories (Walentynowicz, Raes, Van Diest, & Van den Bergh, Reference Walentynowicz, Raes, Van Diest and Van den Bergh2017). All of these studies were exploratory in nature.

Prevalence

Only seven studies used semi-structured clinical interviews based on DSM-5 criteria to diagnose SSD (Calabro et al., Reference Calabro, Ceccarini, Calderone, Lippi, Piaggi, Ferrari and Santini2019; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020; Fergus, Kelley, & Griggs, Reference Fergus, Kelley and Griggs2019; Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Rafanelli, Roncuzzi, Sirri and Fava2013; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Chang and Liao2016; Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018; Umemura et al., Reference Umemura, Tokura, Ito, Kobayashi, Tachibana, Miyauchi and Kurita2019). Of these, Fergus et al., was conducted in primary care patients; the others were in specialized patient populations. All other studies used proxy-diagnosis operationalized by a combination of self-report questionnaires or by clinical determination of SSD. Prevalence studies in the general population using diagnostic criterion standard interviews are completely missing. Two studies reported data from randomly selected, adult, population-based samples using self-report questionnaires assessing previously considered SSD criteria (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Davies, Jackson, Littlewood, Chew-Graham, Tomenson and McBeth2012; Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013; Rief et al., Reference Rief, Mewes, Martin, Glaesmer and Braehler2011). SSD frequency rates in different medical and non-medical populations are summarized in Fig. 2. In general population studies, the frequency of proxy diagnosis for SSD varied between 6.7 and 17.4% [mean frequency 12.9% (95% confidence interval (CI) 12.5–13.3%)]. In studies conducted in non-specialized general medicine settings, frequency rates ranged from 3.5 (Suzuki, Ohira, Noda, & Ikusaka, Reference Suzuki, Ohira, Noda and Ikusaka2017) to 45.5% [mean frequency 35% (95% CI 33.8–36.3%)] with the highest reported frequency rate in patients with medically unexplained symptoms. In diverse specialized care settings (e.g. pulmonology, cardiology, endocrinology, pain) including a pediatric emergency department (Cozzi et al., Reference Cozzi, Minute, Skabar, Pirrone, Jaber, Neri and Barbi2017), SSD frequency ranged between 5.8 and 52.9% [mean frequency 23.6% (95% CI 22.3–25%)]. The highest frequency of SSD was observed within mental health care settings specialized in SSD treatment with frequency rates ranging between 40.3 and 77.7% [mean frequency 60.1% (95% CI 57.8–62.4%)]. The current lack of studies examining the prevalence of SSD based on criterion-standard interviews is a major research gap, precluding reliable estimates of the prevalence of SSD.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of frequency estimates on somatic symptom disorder (with 95% CI). Of note, almost all frequencies estimates are based on proxy diagnoses of SSD, using self-report questionnaires or clinical judgement. The vertical lines indicate the mean values across several studies of a comparable setting (with 95% CI). Underlined references refer to studies in children and/or adolescents. *Data reported in this paper are based on Creed et al., Reference Creed, Davies, Jackson, Littlewood, Chew-Graham, Tomenson and McBeth2012.

Development and course of SSD

Characteristics of adolescent SSD

A cross-sectional population-based study among adolescents (van Geelen et al., Reference van Geelen, Rydelius and Hagquist2015) indicated that in those with serious psychological concerns regarding health and illness, reporting three or more persistent distressing somatic symptoms was significantly more common than reporting one or two. The most commonly reported somatic symptoms were unrefreshing sleep and headache, while the most commonly reported psychological symptoms were illness worries. Medical and psychiatric comorbidity was highest in the group reporting more than three somatic symptoms plus health/illness concerns.

A retrospective cohort study of adolescents admitted to a tertiary children's hospital with SSD or conversion disorder observed that 45% of the presenting symptoms were neurological and 39% involved pain (Gao, McSwiney, Court, Wiggins, & Sawyer, Reference Gao, McSwiney, Court, Wiggins and Sawyer2018). Two-thirds of adolescent SSD patients had at least one medical condition.

Bizzi and colleagues (Bizzi et al., Reference Bizzi, Cavanna, Castellano and Pace2015) compared inpatients with SSD v. disruptive behavior disorders and observed significant presence of insecure attachment in more than a half of the patients in both groups, but no significant differences between them in sociodemographic characteristics, attachment styles, or post-traumatic symptoms. The same group (Bizzi, Ensink, Borelli, Mora, & Cavanna, Reference Bizzi, Ensink, Borelli, Mora and Cavanna2019) reported higher rates of insecure and disorganized attachment in school-aged children with SSD compared to healthy controls. Further, mentalization ability operationalized as reflective functioning was significantly lower in SSD children as compared to healthy controls. Another study (Hatta, Hosozawa, Tanaka, & Shimizu, Reference Hatta, Hosozawa, Tanaka and Shimizu2019) observed no more traits of autism in adolescents with SSD than in healthy controls.

Characteristics of late-life SSD

A small cross-sectional study in late-life outpatients found that those with severe SSD had more cognitive impairment than those with milder SSD and healthy age-matched controls, but sampling bias prevents drawing reliable conclusions (Inamura et al., Reference Inamura, Shinagawa, Nagata, Tagai, Nukariya and Nakayama2015).

Course of SSD

After inpatient treatment of adolescents with clinically diagnosed SSD, complete remission was observed in 49% (n = 18), response in 32% (n = 12), and no changes in 19% (n = 7) (Gao et al., Reference Gao, McSwiney, Court, Wiggins and Sawyer2018). Complete recovery after discharge was almost 20 times more likely in adolescents whose families fully accepted the SSD diagnosis compared to families with partial or no acceptance. Additionally, readmitted patients were eight times less likely to completely recover compared to first admission patients. In their 1-year prospective study of SSD in adult outpatients with vertigo and dizziness, a persistence rate of 82% and a remission rate of 18% was observed (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017). Finally, in a sample of SSD inpatients, ambivalent treatment motivation was related to more negative treatment outcomes (Mander et al., Reference Mander, Schaller, Bents, Dinger, Zipfel and Junne2017).

Risk and prognostic factors

Risk factors for SSD

A prospective study in patients with vertigo and dizziness (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017) found that those who developed SSD within the 1-year study period had higher baseline levels of health anxiety, were more catastrophizing, had a stronger self-concept of bodily weakness, showed more illness-related behaviors (e.g. taking medication), and had higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Prognostic factors for SSD remission

The same study showed that patients who recovered from SSD during the study period reported less catastrophizing at baseline compared with patients who did not recover (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017).

Prognostic factors for SSD associated outcomes

In a 4-year prospective general population study, SSD at baseline predicted the development of higher subjective impairment, health care utilization, and numbers of symptoms at 1-year and 4-year follow-ups (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Rief, Klaus, Brähler and Mewes2017). In a related prospective general population study, lower somatic symptom attribution and higher health anxiety were predictors of the number of medically unexplained symptoms after 4 years, while psychological variables did not predict impairment (Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Rief, Brähler, Martin, Glaesmer and Mewes2015). SSD at admission predicted poorer physical and mental functioning at 1-year follow-up in an inpatient sample with anxiety, depression, or somatoform disorders (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2013). Additional predictors of limited physical functioning were a self-concept of bodily weakness, intolerance of bodily complaints, poor health habits, and somatic illness attributions. Finally, another prospective study indicated that the number of somatic symptoms and health anxiety were predictors of health care use 1 year later (Tomenson et al., Reference Tomenson, McBeth, Chew-Graham, MacFarlane, Davies, Jackson and Creed2012).

Culture-related diagnostic issues

Although international studies of functional syndromes exist, no study could be identified that applied the DSM-5 criteria for SSD and examined them in a transcultural comparison.

Gender-related diagnostic issues

A cross-sectional adolescent general population study reported that significantly more girls than boys reported problems regarding persistent distressing somatic symptoms (van Geelen et al., Reference van Geelen, Rydelius and Hagquist2015). However, in a large study in general hospital outpatients (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020) no gender differences in the prevalence of SSD were reported. An experimental study (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liao, Tu, Yang, Kuo and Gau2019) tested whether heart rate variability differentiated healthy controls from patients with SSD. Compared to women without SSD, women with SSD showed a greater decrease in vagal activity when viewing stimuli related to somatic distress. This effect was not found in men.

Suicide risk

No studies could be considered for review.

Functional consequences

Functional impairment compared to healthy controls

Consistently across all six clinical adult studies, patients with SSD reported higher levels of impairment in terms of lower quality of life and functioning, and higher disability compared to individuals not meeting SSD criteria (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020; Carmassi et al., Reference Carmassi, Dell'Oste, Ceresoli, Moscardini, Bianchi, Landi and Dell'Osso2019; Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016; Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Rafanelli, Roncuzzi, Sirri and Fava2013; Häuser et al., Reference Häuser, Bialas, Welsch and Wolfe2015; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Ma, Lin and Huang2019). In addition, higher health care use and disability in individuals with SSD compared to those without were reported in two studies examining the same general population sample (Rief et al., Reference Rief, Mewes, Martin, Glaesmer and Braehler2011; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Rief, Klaus, Brähler and Mewes2017). One study examining adolescents showed higher levels of functional impairment in SSD compared to healthy controls and individuals with somatic symptoms without psychological features (van Geelen et al., Reference van Geelen, Rydelius and Hagquist2015).

Comparisons with former diagnostic classifications

Six studies compared functional consequences in SSD to former or other proposed classifications for persistent somatic symptoms. Comparing SSD with DSM-IV or ICD-10 somatoform disorders, two studies with psychosomatic outpatient and inpatient samples reported lower mental quality of life in SSD (Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018; Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012; 2013). These studies found similar (Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012; 2013) or higher (Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018) physical quality of life in SSD. No differences were found in health care use. Higher disability levels and health care use were reported in SSD compared to IAD (Newby et al., Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017).

Relation with SSD severity

Six studies examined the relationship between SSD severity and functional consequences. Consistently, they reported increasing levels of impairment, health care use and decreasing quality of life with increasing number and severity of B-criteria across psychosomatic and other secondary care settings and the general population (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Radziej and Lahmann2016; Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Murray, Voigt, Herzog, Gierk, Kroenke and Löwe2016; Toussaint, Löwe, Braehler, & Jordan, Reference Toussaint, Löwe, Braehler and Jordan2017; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Voigt, Braukhaus, Herzog and Löwe2013; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Zhang, Wei, Leonhart, Fritzsche, Mewes and Schaefert2017). In particular, the Somatic Symptom Disorder B-Criteria Scale (SSD-12), a self-report questionnaire assessing SSD B-criteria, has been shown to be a valid predictor of quality of life and health care use (Kop, Toussaint, Mols, & Löwe, Reference Kop, Toussaint, Mols and Löwe2019; Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Murray, Voigt, Herzog, Gierk, Kroenke and Löwe2016, 2017).

Health anxiety and somatic symptom burden as predictors

A large prospective general population study found health anxiety and somatic symptom burden to be independently related to functional impairment (Lee, Creed, Ma, & Leung, Reference Lee, Creed, Ma and Leung2015). Klaus et al. found somatic symptoms to be more relevant in predicting impairment and health care use than psychological features (Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Rief, Brähler, Martin, Glaesmer and Mewes2015).

Differential diagnosis

Illness Anxiety Disorder (IAD)

Given that IAD is diagnosed when there are no or only minimally distressing persistent somatic symptoms, by DSM-5 definition, a patient can either be diagnosed with SSD or IAD, but not both (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Nevertheless, recent research reported comorbidity of 8% of IAD and SSD (Fergus et al., Reference Fergus, Kelley and Griggs2019) and that different raters sometimes disagree in their diagnostic classification of IAD and SSD (Axelsson et al., Reference Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn and Hedman2016). Other authors have questioned the utility of distinguishing them at all, as the diagnoses may have more in common than sets them apart, as reported in a case-control study that observed no significant differences between IAD and SSD regarding health anxiety, illness behavior, somatic symptom attributions, and physical concerns (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Kerstner, Witthoeft, Diener, Mier and Rist2016).

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder is indicated as a differential diagnosis in DSM-5, yet raters in an interview study disagreed whether panic disorder should be an additional diagnosis or whether panic symptoms were part of SSD (Axelsson et al., Reference Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn and Hedman2016).

Comorbidity

Comorbidity with mental disorders

Most studies assessing other mental disorders or self-reported psychopathological symptoms in patients with SSD found high comorbidity rates with depression and anxiety whereas other psychiatric comorbidities were rarely assessed. The three studies shown in Fig. 3 investigated mental comorbidities in specific clinical outpatient samples with diagnostic interviews (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Kerstner, Witthoeft, Diener, Mier and Rist2016; Fergus et al., Reference Fergus, Kelley and Griggs2019; Newby et al., Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Forest plot of frequency rates of mental comorbidities in somatic symptom disorder (with 95% CI).

In another general hospital outpatient sample, patients with SSD showed higher depression and anxiety levels than patients without SSD (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020). Four studies observed higher self-reported depression and anxiety rates in patients with SSD compared to healthy controls (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Kerstner, Witthoeft, Diener, Mier and Rist2016; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liao, Yang, Kuo, Chen, Chen and Gau2017, 2019; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Ma, Lin and Huang2019). Furthermore, three studies found significant associations between the SSD-12 score and depression and anxiety levels in the general population (Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Löwe, Braehler and Jordan2017), in a primary care setting (Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Riedl, Kehrer, Schneider, Löwe and Linde2018), and in a psychosomatic outpatient sample (Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Murray, Voigt, Herzog, Gierk, Kroenke and Löwe2016). Patients with SSD also showed higher depression (Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016) and anxiety severity levels than patients with DSM-IV or ICD-10 somatoform disorders (Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016; Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018).

SSD severity was not related to depression and anxiety severity in one study (Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018), while another (Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016) found higher depression severity in moderate compared to mild SSD. Fergus and colleagues found that the severity of health anxiety was positively associated with the rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity (Fergus et al., Reference Fergus, Kelley and Griggs2019). In another study, the complexity of SSD was associated with higher self-reported depression and anxiety (van Eck van der Sluijs et al., Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, de Vroege, van Manen, Rijnders and van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). Comorbid depression was found to be associated with poorer overall functioning and quality of life (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Ma, Lin and Huang2019). In a cross-sectional study of patients with vertigo and dizziness, the rate of psychiatric comorbidities was highest in SSD patients who fulfilled all three B-criteria (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Radziej and Lahmann2016). Another study on this sample observed that comorbid depression and anxiety disorders were associated with the persistence of SSD (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017).

Comorbidity with physical conditions, including functional somatic syndromes

In studies examining different physical conditions, SSD criteria were met by 41.5% of patients with semantic dementia, 11.2% of patients with Alzheimer's disease (Gan, Lin, Samimi, & Mendez, Reference Gan, Lin, Samimi and Mendez2016), 25% of female patients with non-HIV lipodystrophy (Calabro et al., Reference Calabro, Ceccarini, Calderone, Lippi, Piaggi, Ferrari and Santini2019), and 18.5% of patients with congestive heart failure (Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Rafanelli, Roncuzzi, Sirri and Fava2013). In individuals with fibromyalgia, 25.6% met SSD criteria (Häuser et al., Reference Häuser, Bialas, Welsch and Wolfe2015), and they had higher depression rates compared to fibromyalgia patients without SSD. In a smaller ambulatory study of fibromyalgia patients, 38.5% fulfilled the A- and B-criteria of SSD (Klaus et al., Reference Klaus, Fischer, Doerr, Nater and Mewes2017). In a study assessing somatic conditions in patients with SSD, 28.8% had asthma, 23.1% had a circulatory condition, and 13.5% had gout, rheumatism or arthritis (Newby et al., Reference Newby, Hobbs, Mahoney, Wong and Andrews2017). In a population-based study, patients with different medical conditions scored higher on the SSD-12 compared to those free of these conditions, and the severity of the medical condition was associated with the SSD-12 score (Kop et al., Reference Kop, Toussaint, Mols and Löwe2019).

Comorbidity in children and adolescents

In a study in children and adolescents with SSD, no elevated levels of post-traumatic symptomatology were found (Bizzi et al., Reference Bizzi, Cavanna, Castellano and Pace2015). In a study including children with psychogenic and functional breathing disorders, 5.8% were diagnosed with persistent SSD (Orengul et al., Reference Orengul, Ertaş, Ustabas Kahraman, Yazan, Çakır and Nursoy2020).

Discussion

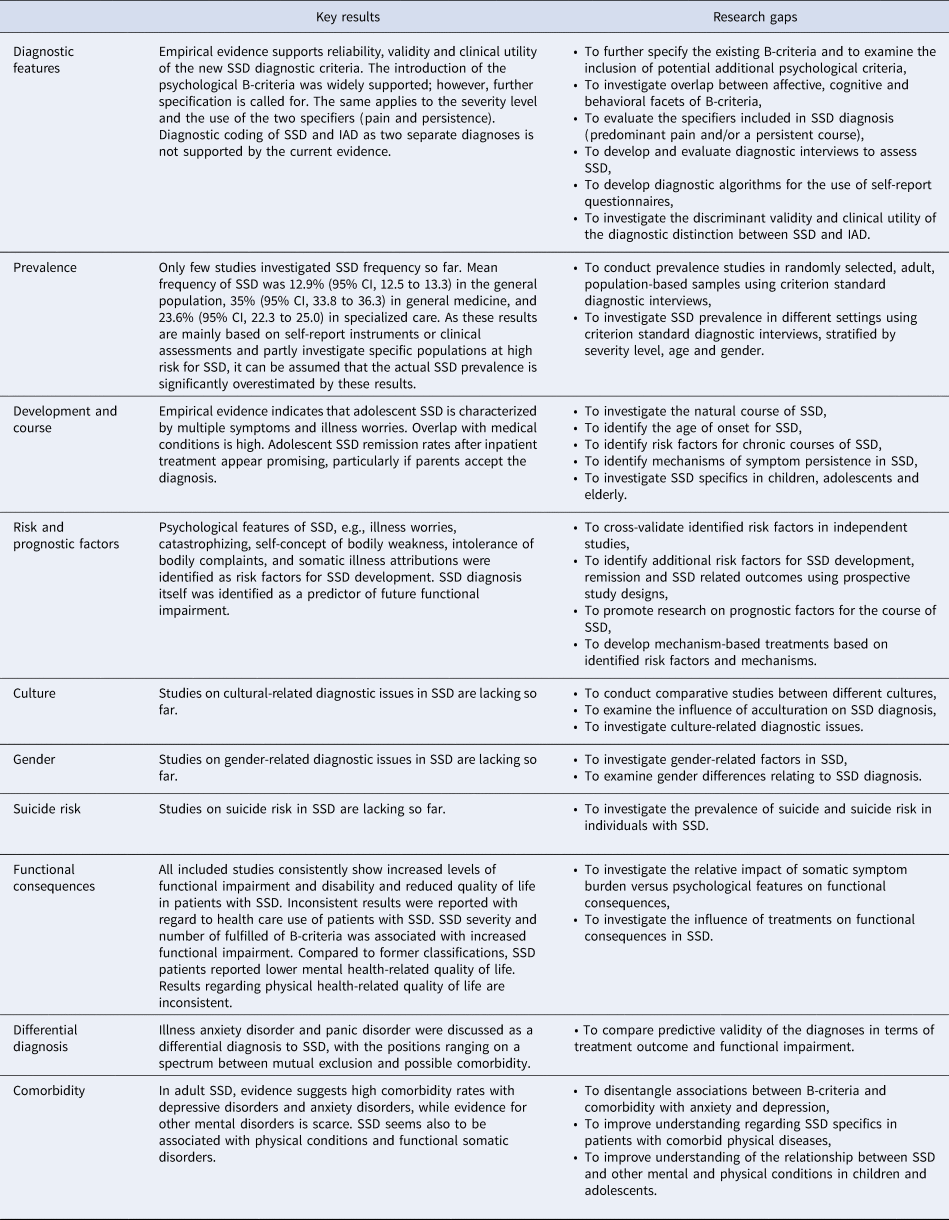

This scoping review summarizes the continuously growing scientific evidence regarding SSD after its introduction in DSM-5 in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Even though available research does not yet provide data on all DSM-5 text sections, it does allow a first assessment of the new diagnosis. Key research findings are discussed below and summarized together with the corresponding research gaps in Table 3.

Table 3. Key results of scoping review and resulting research gaps in the context of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder

Reliability, validity, clinical utility, functional consequences

When a new diagnosis is introduced, it is expected to surpass its predecessor, especially in terms of reliability and validity. In the case of SSD, the available data demonstrate that it has better reliability and validity than its predecessor diagnoses. With regard to reliability, an acceptable to good interrater-reliability can be assumed for SSD, especially in comparison with other mental disorders (Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013). The findings that patients with SSD display higher disability and lower health-related quality of life compared to the general population (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Jiang and Leonhart2020; Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Chang and Liao2016) also support construct validity, as do the findings that with increasing severity of SSD, functional impairment also increases (Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Murray, Voigt, Herzog, Gierk, Kroenke and Löwe2016; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Voigt, Braukhaus, Herzog and Löwe2013). Notably, the group of individuals identified by the new diagnosis of SSD is not identical to the group described by the previous diagnosis of somatization disorder. Regarding severity, it appears that SSD includes more severe cases in terms of mental quality of life, and perhaps somewhat milder cases in terms of physical quality of life in comparison to former classifications (Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018; Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Wollburg, Weinmann, Herzog, Meyer, Langs and Löwe2012). These results are not surprising considering that the new B-criteria emphasize psychological burden rather than somatic symptom count. Initial studies also indicate improved acceptance and clinical usefulness of SSD compared to its predecessor, which is most likely due to the added psychological criteria (B-criteria) and the removal of the need for medical diagnosis exclusion. However, the diagnostic distinction between SSD and IAD remains questionable: Based on present findings, IAD might be considered a milder form of SSD (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Kerstner, Witthoeft, Diener, Mier and Rist2016).

Individual diagnostic criteria

Our review yielded mixed results regarding the reliability of the B-criteria (Axelsson et al., Reference Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn and Hedman2016; Regier et al., Reference Regier, Narrow, Clarke, Kraemer, Kuramoto, Kuhl and Kupfer2013; Rief & Martin, Reference Rief and Martin2014), and several alternative psychological features have been proposed (Martin & Rief, Reference Martin and Rief2011). The empirically justified abolition of the medical inexplicability of the somatic symptoms was generally well-received by the clinical and scientific communities. Further, the diagnostic specifiers included in the diagnosis (predominant pain, persistence, and severity) were addressed in only a few studies (Axelsson et al., Reference Axelsson, Andersson, Ljotsson, Wallhed Finn and Hedman2016; Katz, Rosenbloom, & Fashler, Reference Katz, Rosenbloom and Fashler2015; Rief & Martin, Reference Rief and Martin2014). Study results on biomarkers of SSD are unlikely to be included in the diagnostic criteria in the near future due to their small sample sizes, exploratory nature, and rarely replicated results thus far. In summary, the greatest need for improvement of the SSD diagnostic criteria appears to be measurable and more precise diagnostic B-criteria. To date, it remains unclear how exactly the term “excessive” can be operationalized for symptom-related cognitions, anxiety, and behavior. A first attempt at operationalizing excessiveness can be found in a study (Toussaint, Hüsing, Kohlmann, Brähler, & Löwe, Reference Toussaint, Hüsing, Kohlmann, Brähler and Löwe2021), which describes that individuals with SSD spent an average of 4 h a day preoccupied with their somatic symptoms. Validated scales could also help operationalize cut-offs between normal and clinically abnormal range for the diagnostic B-criteria. Thus, a more precise definition of the content and cut-offs for the B-criteria definitely remains a task for the next edition of the DSM.

Prevalence

Reliable data on the prevalence of SSD are still scarce. Only two studies that used proxy estimates of SSD, reported data from adult population-based surveys (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Davies, Jackson, Littlewood, Chew-Graham, Tomenson and McBeth2012; Dimsdale et al., Reference Dimsdale, Creed, Escobar, Sharpe, Wulsin, Barsky and Levenson2013; Rief et al., Reference Rief, Mewes, Martin, Glaesmer and Braehler2011) with frequency rates of 6.7 and 17.4% being higher than DSM-IV somatization disorder (~1–6%) (Creed & Barsky, Reference Creed and Barsky2004; Escobar, Burnam, Karno, Forsythe, & Golding, Reference Escobar, Burnam, Karno, Forsythe and Golding1987), but lower than undifferentiated somatoform disorders (~20%) (Grabe et al., Reference Grabe, Meyer, Hapke, Rumpf, Freyberger, Dilling and John2003). When making this comparison, it is important to keep in mind that the prevalence estimates for SSD are derived primarily from clinical assessments and self-report questionnaires, and not based on criterion standard diagnostic interviews. As self-report questionnaires and clinical assessment usually lead to an overestimation of the prevalence of mental disorders compared to diagnostic interviews, it can be assumed that the currently available data actually overestimate SSD prevalence. Since diagnoses in the available studies were based on self-report data, the mean 13% frequency of SSD in the general population indicates a considerable at-risk subgroup rather than a group with reliable diagnoses of SSD. All other studies included in this scoping review reported data from rather specific clinical settings, many of them limited by small samples sizes. In these studies, frequency rates covered a wide range from 3.5 to 77.7%. So far, none of the studies reported any prevalence data based on the SSD severity specifiers or age-adjusted and/or sex-adjusted prevalence estimates, or estimates stratified by age or gender. Studies in pediatric samples seem to find lower frequency rates. Our conclusions are tempered by the wide methodological heterogeneity of the included studies, i.e., different sample characteristics, sampling strategies, and varying diagnostic approaches. In conclusion, the concern that the new diagnosis of SSD might be overinclusive (Frances, Reference Frances2013) cannot be completely dismissed, since the data on prevalence thus far are relatively unreliable. Accurate population-based estimates of SSD using criterion standard diagnostic interviews are needed in order to inform health care planning and resource allocation.

Development, course, and risk factors

The evidence on SSD development, course and risk factors is unfortunately sparse and characterized by imprecise operationalization of SSD diagnosis often related to former diagnostic concepts. Whereas preliminary evidence on adolescent SSD suggests a frequent involvement of pain and illness worries in adolescent SSD along with promising remission rates in those who seek treatment (Gao et al., Reference Gao, McSwiney, Court, Wiggins and Sawyer2018; van Geelen et al., Reference van Geelen, Rydelius and Hagquist2015), current evidence allows no conclusions on late-life SSD. In treated adult patients, remission rates appear considerably lower (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017) and influenced by interpersonal problems, somatic symptom severity and stress. Catastrophizing and the ideation of bodily weakness might be relevant aspects affecting SSD development and course (Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Dinkel, Radziej, Becker-Bense and Lahmann2017). However, to date, no study of SSD has yet investigated the age of onset, duration of untreated illness, natural course, risk factors for chronicity, or mechanisms of symptom persistence.

Differential diagnosis and comorbidity

Differential diagnosis in SSD has rarely been investigated. Further research seems necessary to investigate how and if SSD and IAD differ from each other. Similar to DSM-IV somatization disorder (Kohlmann, Gierk, Hilbert, Brähler, & Löwe, Reference Kohlmann, Gierk, Hilbert, Brähler and Löwe2016; Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Spitzer, Williams, Mussell, Schellberg and Kroenke2008), SSD frequently co-occurs with depressive and anxiety disorders. Reasons for the overlap of SSD, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders may be partially overlapping diagnostic criteria, shared biological and psychological diathesis, the bidirectional risk for development of the other disorders, and a common basic construct (Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Spitzer, Williams, Mussell, Schellberg and Kroenke2008). Recent evidence also indicates that the SSD B-criteria are highly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms (Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018; Kop et al., Reference Kop, Toussaint, Mols and Löwe2019; Toussaint et al., Reference Toussaint, Murray, Voigt, Herzog, Gierk, Kroenke and Löwe2016, 2017). Thus, comorbidity rates of depression and anxiety may be higher in SSD compared to earlier diagnoses (Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016; Hüsing et al., Reference Hüsing, Löwe and Toussaint2018). Moreover, the pattern of the B-criteria, the severity/complexity of SSD symptoms, and the number of fulfilled components (affective, cognitive, behavioral) seem to be associated with the frequency of comorbid mental disorders (Claassen-van Dessel et al., Reference Claassen-van Dessel, van der Wouden, Dekker and van der Horst2016; Fergus et al., Reference Fergus, Kelley and Griggs2019; Limburg et al., Reference Limburg, Sattel, Radziej and Lahmann2016; van Eck van der Sluijs et al., Reference van Eck van der Sluijs, de Vroege, van Manen, Rijnders and van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). A variety of studies showed that among patients with various somatic diseases, roughly a quarter suffer from SSD. This suggests that it is important to consider the diagnosis of SSD in patients with somatic diseases in order to adequately treat them. Although no suitable reference could be identified, it should be mentioned that excessive somatic focus is a feature of both body dysmorphic disorder and SSD, but in the former, the patient is concerned with appearance, while in SSD the worry is about being ill.

Further research gaps

Results of this scoping review indicate a large research gap regarding cultural- and gender-related aspects, as well as suicide risk in SSD (see also Table 3).

Strengths and weaknesses

Results of the present scoping review must be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, it is in the nature of a scoping review, that we could only report the results of studies that were found during our predefined literature search. Results may thus not completely reflect the state of knowledge on SSD; but rather the currently published state of knowledge. Second, the included studies were very heterogeneous in terms of study design, sample size, and operationalization of SSD diagnosis. In line with scoping review methods (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun, Levac and Straus2018), we did not conduct a formal quality assessment of all included research papers. Nevertheless, we ensured sufficient study quality by formulating strict requirements for study inclusion. Third, our search strategy was based on the predefined DSM-5 text sections. Other relevant aspects, e.g., the efficacy of treatments for SSD, were not considered and should be addressed in future reviews.

Conclusion

Since the introduction of SSD in 2013, evidence has been accumulating that the new DSM-5 diagnosis appears to be reliable, valid and clinically useful. The introduction of positive psychological criteria and the elimination of the need to exclude medical explanations might have contributed to improved validity and acceptance. However, diagnostic changes in the ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2021), other newly proposed classifications such as “functional somatic disorders” (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Fink, Henningsen, Löwe, Rief and Group2020), and various other diagnostic conceptualizations for persistent somatic symptoms (Weigel et al., Reference Weigel, Hüsing, Kohlmann, Lehmann, Shedden-Mora and Toussaint2017) will require further scientific debate.

Thus far, it remains unclear how often the diagnoses of SSD or the respective ICD-11 diagnosis of BDD are actually used in different fields of medicine and countries (Kohlmann, Löwe, & Shedden-Mora, Reference Kohlmann, Löwe and Shedden-Mora2018). This is unfortunate because a missed diagnosis of SSD might prevent patients from receiving appropriate treatment. Valid self-report instruments for the diagnosis of SSD are available for the A-criterion, e.g., with the Somatic Symptom Severity Scale-8 (SSS-8) (Gierk et al., Reference Gierk, Kohlmann, Kroenke, Spangenberg, Zenger, Brähler and Löwe2014) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) (Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Löwe, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe2010), and for the B-criteria, e.g., with the Somatic Symptom Disorder B-Criteria Scale (SSD-12) (Toussaint, Hüsing, Kohlmann, & Löwe, Reference Toussaint, Hüsing, Kohlmann and Löwe2020). Beyond these instruments, the recommendations of the EURONET-SOMA group for assessing core outcome domains may help to improve the comparability of results from clinical trials in the future (Rief et al., Reference Rief, Burton, Frostholm, Henningsen, Kleinstäuber, Kop and van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). In addition, research in recent years has led to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the perception and experience of persistent somatic symptoms (Henningsen et al., Reference Henningsen, Gündel, Kop, Löwe, Martin, Rief and Van den Bergh2018). Continuing this research has the potential to lay the groundwork for the development of mechanism-based therapeutic approaches in the near future. We hope that the diagnosis of SSD will be appropriately used in patient care and intensively researched to increase the knowledge about SSD and fill the research gaps (Table 3).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004177

Acknowledgements

James Levenson, MD, was appointed as section editor for the chapter “somatic symptom and related disorders” for the DSM-5 Text Revision by the American Psychiatric Association. Bernd Löwe, MD, was appointed as a reviser for the text on “somatic symptom disorder” for the DSM-5 Text Revision by the American Psychiatric Association. Neither author received an honorarium for these tasks.

Financial support

This research was conducted without external funding; no author did receive specific funding for the preparation of this scoping review from any funding agency or any commercial or non-profit institution.

Conflict of interest

None.