Introduction

Panic disorder (PD) is an anxiety disorder characterized by repeated and unforeseen episodes of panic attacks. A panic attack is an abrupt onset of extreme fear or discomfort that reaches its peak within a few minutes and involves various physical and cognitive symptoms. PD typically manifests during late adolescence or early adulthood, with an average onset age of nearly 20–24 years. PD is more prevalent in women than in men. Specifically, women are nearly twice as likely to experience PD as men (Sansone, Sansone, & Righter, Reference Sansone, Sansone and Righter1998). PD affects ~2%–3% of the general population (Lydiard, Reference Lydiard1996), and it often coexists with other mental health disorders, such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder (MDD), and substance use disorder (SUD) (Lecrubier, Reference Lecrubier1998). Psychiatric comorbidities may complicate the diagnosis and treatment of PD, leading to severe consequences such as chronic health problems, concomitant mental disorders, social and vocational deficits, increased healthcare expenditures, and substance dependence. During panic episodes, continual anxiety may substantially diminish the quality of life, lead to avoidance behaviors, and increase the risk of long-term psychological distress and even suicidality (Katschnig & Amering, Reference Katschnig and Amering1998).

Several studies have attempted to examine the association of PD with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death. Weissman et al. (Weissman, Klerman, Markowitz, & Ouellette, Reference Weissman, Klerman, Markowitz and Ouellette1989) conducted the first study on the likelihood of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in patients with PD. They examined a random sample of 18,011 adults from five communities in the United States, and they reported that 20% of those with a lifetime diagnosis of PD had attempted suicide. The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study demonstrated that PD was associated with elevated likelihoods of suicidal ideation (odds ratio: 2.23) and suicide attempts (2.01) (Sareen et al., Reference Sareen, Cox, Afifi, de Graaf, Asmundson, ten Have and Stein2005). Evidence showed varying rates of suicide attempts among patients with PD, ranging from 0.7% (Beck, Steer, Sanderson, & Skeie, Reference Beck, Steer, Sanderson and Skeie1991) to 2% (Friedman, Jones, Chernen, & Barlow, Reference Friedman, Jones, Chernen and Barlow1992; Woodruff-Borden, Stanley, Lister, & Tabacchi, Reference Woodruff-Borden, Stanley, Lister and Tabacchi1997) and even 42% (Lepine, Chignon, & Teherani, Reference Lepine, Chignon and Teherani1993). Kinley et al. (Kinley, Walker, Mackenzie, & Sareen, Reference Kinley, Walker, Mackenzie and Sareen2011) examined a population-based sample of active Canadian military personnel and reported that PD and panic attacks were associated with an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation. Pilowsky et al. (Pilowsky, Wu, & Anthony, Reference Pilowsky, Wu and Anthony1999) examined the correlation between suicide attempts and panic attacks in a community-based sample of adolescents. They discovered that adolescents who experienced panic attacks were three times more likely to exhibit suicidal ideation and approximately two times more likely to attempt suicide compared with those who did not, even after demographic factors, MDD, alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use were adjusted for. Overall, these findings indicate that panic attacks or PD may increase the risk of suicide.

Despite these efforts, several studies have failed to confirm an increase in suicidality in patients with PD (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Sanderson and Skeie1991; Overbeek, Rikken, Schruers, & Griez, Reference Overbeek, Rikken, Schruers and Griez1998; Rudd, Dahm, & Rajab, Reference Rudd, Dahm and Rajab1993; Warshaw, Dolan, & Keller, Reference Warshaw, Dolan and Keller2000). Zonda et al. (Zonda, Nagy, & Lester, Reference Zonda, Nagy and Lester2011) examined a sample of 281 outpatients with PD without comorbid psychiatric disorders; they were followed up for an average of 5 years. They reported no difference in the likelihood of suicide mortality between those with PD without comorbid diseases and the general population. Weissman et al. (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Klerman, Markowitz and Ouellette1989) explored the effect of psychiatric comorbidities on the risk of PD-related suicide but surprisingly found no associations between additional suicide outcomes and the coexistence of MDD and alcohol or drug misuse. Later, Johnson et al. (Johnson, Weissman, & Klerman, Reference Johnson, Weissman and Klerman1990) compared the rates of suicide attempts between patients with uncomplicated PD (i.e. without schizophrenia or major affective disorders) and those with other psychiatric disorders. They discovered that patients with uncomplicated PD (7%) had consistently higher lifetime rates of suicide attempts compared with normal controls (1%). Similar rates were observed in those with uncomplicated MDD (7.9% suicide attempts). These results indicate that PD, whether uncomplicated or comorbid, is associated with suicide attempts, and the risks associated with PD are similar to those observed for patients with MDD (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Weissman and Klerman1990). A clinical study of 730 individuals who sought emergency psychiatry consultation because of suicide attempts revealed that depression, anxiety (including panic attacks), alcohol or substance abuse, and psychosis/rational thought loss account for a significant proportion (Randall, Sareen, & Bolton, Reference Randall, Sareen and Bolton2020). Compared with the general population, Chang et al. (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Pan, Chen, Chen, Su, Tsai, Chen and Kuo2022) examined the mortality risk for 298,466 patients with PD and found that the risk was highest for suicide (mortality rate ratio [MRR]: 4.94, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.32–5.72). They further revealed that patients with PD who had a comorbid SUD exhibited higher suicide risk (MRR: 9.45, 95% CI: 6.29–17.85) compared with those who did not. In contrast to these findings, subsequent research has indicated that the associations between PD and suicidality are likely because of the presence of concurrent SUD, bipolar disorder, and MDD rather than PD serving as a standalone risk factor for increased suicidality (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Sanderson and Skeie1991; Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Jones, Chernen and Barlow1992; Rudd et al., Reference Rudd, Dahm and Rajab1993; Starcevic, Bogojevic, Marinkovic, & Kelin, Reference Starcevic, Bogojevic, Marinkovic and Kelin1999).

According to the literature, patients with PD exhibit varying rates of suicidality. Nevertheless, the potential effect of psychiatric comorbidities on the risk of suicide in patients with PD remains unclear, presumably because of the differences between study methodologies and the ambiguity surrounding the concept of suicidality. Suicidality is typically identified through suicidal ideation or purpose, particularly in the presence of a well-developed suicidal plan. Suicidality may refer to suicidal ideas, plans, gestures, or attempts. These discrepancies may be because of the settings used for patient recruitment, the small sample sizes used, or the fact that the majority of relevant research has adopted a cross-sectional study design. To address these discrepancies, additional large-scale population-based follow-up studies are required. In this study, we used a longitudinal cohort technique to evaluate the risk of suicide death in patients with PD. We utilized a nationwide, population-based insurance claims database in our analysis to obtain a large sample and conduct long-term follow-up. Our primary goal was to determine whether PD is an independent risk factor for suicide and identify the additional risks posed by specific psychiatric comorbidities.

Methods

Data source. The Ministry of Health and Welfare’s Taiwan Health and Welfare Data Science Center audits and makes accessible for research purposes the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which includes comprehensive healthcare data on almost 99.7% of Taiwan’s population. Individual medical records are anonymous in the NHIRD to safeguard individuals’ privacy. We linked the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database of the NHIRD, which includes all medical records from 2003 to 2017 of the entire Taiwanese population, and the Database of All-cause Mortality, which provides for all-cause mortality records from 2003 to 2017 of the whole Taiwanese population, to analyze the suicide risk among patients with PD. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification is used in Taiwanese clinical practice (ICD-9-CM [2003–2014] or ICD-10-CM [2015–2017]). The institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital approved the study protocol. It waived the requirement for informed consent because de-identified data were used in this study and no participants were actively enrolled. The NHIRD has been used in numerous epidemiological studies in Taiwan (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Su, Chen, Hsu, Huang, Chang and Bai2013; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chang, Chen, Tsai, Su, Li, Tsai, Hsu, Huang, Lin, Chen and Bai2018; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Liang, Tsai, Bai, Su, Chen and Chen2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Bai, Tsai, Su, Chen, Wang and Chen2021).

Inclusion criteria for individuals with PD and the control group. Figure 1 illustrates the study flowchart. The Taiwan NHIRD comprised 29,077,426 subjects. The individuals in the PD group were those who were diagnosed with PD (ICD-9-CM codes: 300.01, 300.21 or ICD-10-CM codes: F40.01, F41.0) by board-certified psychiatrists at least twice (Figure 1). To reduce the confounding effects of age and sex, a 1:4 case–control matched analysis was conducted based on birth year and sex. The control group was selected at random from the whole Taiwanese population after all people who had ever obtained a diagnosis of PD were eliminated from the database (Figure 1). The urbanization level of residence (levels 1–4, most to least urbanized) was assessed as a proxy for health-care availability in Taiwan (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Hung, Chuang, Chen, Weng and Liu2006). The PD diagnosis was regarded as a time-dependent variable. Suicide was identified between 2003 and 2017 from the Database of All-cause Mortality. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores for patients with PD and matched controls were computed. To ascertain the systemic health status of every enrolled subject, the CCI, which consists of 22 physical conditions, was also evaluated (Charlson, Pompei, Ales, & MacKenzie, Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie1987). The CCI includes congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease (mild or moderate/severe), diabetes mellitus (with or without complications), hemiplegia, paraplegia, renal disease, malignancy, leukemia, lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, and AIDS (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie1987; Drosdowsky & Gough, Reference Drosdowsky and Gough2022). We further identified PD-related comorbidities, including schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code: 295 or ICD-10-CM code: F20, F25), bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM codes: 296 except 296.2, 296.3, 296.9, and 296.82 or ICD-10-CM codes: F30, F31), MDD (ICD-9-CM codes: 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311 or ICD-10-CM codes: F32, F33, F34), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (ICD-9-CM code: 300.3 or ICD-10-CM code: F42), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (ICD-9-CM code: 314 or ICD-10-CM code: F90), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (ICD-9-CM codes: 299.0, 299.8, 299.9 or ICD-10-CM codes: F84.0, F84.5, F84.8, F84.9), alcohol use disorder (AUD) (ICD-9-CM codes: 291, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0 or ICD-10-CM code: F10), and SUD (only illicit substances, ICD-9-CM codes: 292, 304, 305 except 305.0 and 305.1 or ICD-10-CM codes: F11, F12, F13, F14, F15, F16, F18, F19), as suicide-related confounding factors in our analysis (Catala-Lopez et al., Reference Catala-Lopez, Hutton, Page, Driver, Ridao, Alonso-Arroyo, Valencia, Macias Saint-Gerons and Tabares-Seisdedos2022; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chang, Tsai, Li, Tsai, Bai, Lin, Su, Chen and Chen2023; Hirvikoski et al., Reference Hirvikoski, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Boman, Larsson, Lichtenstein and Bolte2016). The aforementioned major psychiatric comorbidities also were investigated during the follow-up period for further evaluation of the effect of comorbidities on the risk of suicide. Suicide was identified from the Database of All-cause Mortality. These psychiatric disorders were diagnosed at least twice by board-certified psychiatrists (Huang, Wei, Huang, Wu, & Chan, Reference Huang, Wei, Huang, Wu and Chan2023; Wu, Kuo, Su, Wang., & Dai, Reference Wu, Kuo, Su, Wang. and Dai2020).

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Statistical analysis. We used repeated measure analyses of variance with the general linear models for continuous variables and conditional logistic regressions for nominal variables for between-group comparisons in grouping data. Time-dependent Cox regression models with adjustment for sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, psychiatric comorbidities, and CCI were used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI of subsequent suicide between PD and non-PD groups. Because of a significantly higher risk of suicide death in men than in women (India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide C, 2018), we performed the sex-stratified subanalyses to clarify the suicide risk between men and women with PD. We investigated the effects of psychiatric comorbidities, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, AUD, and SUD, on the suicide risk among individuals with PD in comparison to the control group using Cox regression models with adjustments for sex, birth year, income, levels of urbanization, and CCI. We also assessed the effects of psychiatric comorbidities among patients with PD. The proportional hazards assumptions were verified using the log-minus-log plots, resulting in no considerable violation. A two-tailed p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis Software Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Data Availability Statement. The NHIRD was released and audited by the Department of Health and the Bureau of the NHI Program for Scientific Research (https://www.apre.mohw.gov.tw/). The NHIRD can be accessed through a formal application that is regulated by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Results

The study consisted of a total of 858,685 participants, with 171,737 individuals with PD and age-/sex-matched 686,948 non-PD individuals. Within both cohorts, 38.79% of individuals identified as male, and the majority of individuals were born between the years 1961 and 1970 (Table 1). The PD cohort had higher CCI scores and a greater prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities compared with the control cohort (all P < 0.001). The most prevalent psychiatric comorbidity in PD is MDD, accounting for 63.35% of cases. Bipolar disorder is the second most common comorbidity, occurring in 8.93% of cases (Table 1). The total follow-up duration was 2,540,218 person-year in the PD group and 10,187,864 person-year in the control group, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with PD and matched controls

OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; USD: United States dollar; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

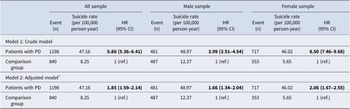

During the follow-up period, a total of 1,198 individuals from the PD cohort and 840 individuals from the control cohort died by suicide. The suicide rates for the PD and control cohorts are 47.16 and 8.25 per 100,000 person-years, respectively (Table 2). Our analysis showed that PD was a significant and independent risk factor for suicide, with an HR of 1.85 and a 95% CI of 1.59–2.14. In addition, the subgroup analyses of both men and women showed a similar pattern (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2. Suicide risk between patients with PD and matched controls

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

# adjusting for sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, psychiatric comorbidities, and CCI.

Bold type indicates statistical significance.

Using Cox regression models with adjustments for sex, birth year, income, levels of urbanization, and CCI, we examined the additive suicide risk among individuals with PD in comparison to the control group in the presence of psychiatric comorbidities, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, ASD, ADHD, AUD, and SUD. Except for ADHD, all of these psychiatric comorbidities were found to tend to increase the risk of suicide (Table 3). In the PD cohort, MDD is the most significant psychiatric comorbidity that elevates the risk of suicide. Compared with the control group, the suicide rate in PD with MDD is 6.08 times higher (95% CI: 5.48–6.74), while it is 2.11 times higher (1.77–2.52) in PD without MDD. In particular, female individuals with PD and MDD had an 8.18-fold higher risk (95% CI: 7.07–9.45) of suicide than control females (Table 3). ASD is the second psychiatric comorbidity with a greater additive increase in suicide rate. Suicide rates in PD with ASD are 4.52 times higher (95% CI: 1.66–12.29) than in the control group, and 1.79 times higher in PD without ASD. Furthermore, we found that the comorbidities of schizophrenia (HR: 3.34, 95% CI: 2.7–4.13), bipolar disorder (3.20, 2.71–3.79), OCD (2.10, 1.64–2.67), AUD (2.99, 2.41–3.72), and SUD (2.82, 2.28–3.47) also increased suicide risk among individuals with PD (Table 3). Interestingly, we discovered that ADHD comorbidity did not increase the suicide risk (HR: 1.55, 95% CI: 0.82–2.93) among individuals with PD (Table 3). Finally, Table 4 shows the suicide risk among patients with PD with psychiatric comorbidities compared with those without psychiatric comorbidities. We found consistent findings that elevated suicide risk was associated with schizophrenia (HR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.77–2.59), bipolar disorder (2.00, 1.73–2.32), MDD (3.08, 2.58–3.66), ASD (2.86, 1.05–7.77), AUD (1.76, 1.45–2.12), and SUD (1.99, 1.64–2.42), respectively (Table 4).

Table 3. Suicide risk between patients with PD with different psychiatric comorbidities and matched controls

OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

# Separate Cox regression models with adjustment of sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, and CCI.

Bold type indicates statistical significance.

Table 4. Effect of psychiatric comorbidities on suicide risk among patients with PD (n = 171,737)

OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder.

# Separate Cox regression models with adjustment of sex, birth year, income, level of urbanization, and CCI.

Bold type indicates the statistical significance.

Discussion

Over the past two decades, studies have increasingly indicated a correlation between PD and suicidal behavior. Several models have been proposed to explain the relationship between PD and suicidality. Nevertheless, studies have yet to determine whether psychiatric comorbidities or panic attacks are responsible for the relatively high risk of suicide observed in patients with PD (Hornig & McNally, Reference Hornig and McNally1995; Huang, Yen, & Lung, Reference Huang, Yen and Lung2010; Johnson & Lydiard, Reference Johnson and Lydiard1998). In addition, few studies have examined suicide mortality in patients with PD. The present population-based cohort study revealed that patients with PD had a higher rate of suicide mortality compared with the control group. After adjusting for various covariates, including sex, birth year, income level, urbanization level, psychiatric comorbidities, and CCI score, we observed that PD was an independent risk factor (1.85-fold) for suicide, with an elevated risk in both men and women. These findings are consistent with those of Weissman et al. (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Klerman, Markowitz and Ouellette1989), who reported that PD is associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, which cannot be explained by the presence of MDD, AUD, or SUD.

PD is associated with an increased risk of suicide mortality, and this can be attributed to diverse factors, including psychological and neurobiological factors. In patients with panic attacks, early onset, increased severity, and extended duration of such attacks may increase the risk of suicide (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yen and Lung2010; Tietbohl-Santos et al., Reference Tietbohl-Santos, Chiamenti, Librenza-Garcia, Cassidy, Zimerman, Manfro, Kapczinski and Passos2019). Patients with panic attacks frequently experience severe physical symptoms and strong, abrupt episodes of fear. These panic episodes may result in long-term stress and emotional distress, which may in turn lead to suicidal thoughts and emotions of hopelessness and helplessness. Nam et al. (Nam, Kim, & Roh, Reference Nam, Kim and Roh2016) studied 223 Korean outpatients with MDD. They compared those with PD (33%) and those without PD (67%) in terms of their history of suicide attempts. They observed that those with both MDD and PD were more likely to have a history of suicide attempts and to exhibit greater levels of impulsivity, depression, and hopelessness compared with those with MDD alone. In another study involving patients with MDD and PD, Yaseen et al. (Yaseen, Chartrand, Mojtabai, Bolton, & Galynker, Reference Yaseen, Chartrand, Mojtabai, Bolton and Galynker2013) discovered that the fear of dying observed during a panic attack increased the likelihood of subsequent suicidal ideation by sevenfold, even when comorbid disorders and demographic factors were controlled for. Regarding neurobiological factors, research has suggested that dysregulation in neurotransmitter systems (e.g. serotonin and norepinephrine) and alterations in brain regions associated with emotion regulation (e.g. amygdala and prefrontal cortex) may underpin both PD and suicidal behavior (Charney, Woods, Krystal, Nagy, & Heninger, Reference Charney, Woods, Krystal, Nagy and Heninger1992; Dresler et al., Reference Dresler, Hahn, Plichta, Ernst, Tupak, Ehlis, Warrings, Deckert and Fallgatter2011; Grove, Coplan, & Hollander, Reference Grove, Coplan and Hollander1997; Rappaport, Moskowitz, Galynker, & Yaseen, Reference Rappaport, Moskowitz, Galynker and Yaseen2014). Kim et al. (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oh, Kim, Lee, Tae, Kim, Choi and Lee2015) conducted a neuroimaging study and revealed no significant difference in gray matter or white matter volume between patients with PD who had attempted suicide and those who had not. Nevertheless, their data indicated that the abnormal integrity of the white matter observed in the internal capsule and thalamic radiations was presumably a key neural factor associated with suicide attempts in patients with PD.

Furthermore, PD commonly co-occurred with agoraphobia, which was also associated with suicide risk (Brown, Gaudiano, & Miller, Reference Brown, Gaudiano and Miller2010; Gros, Pavlacic, Wray, & Szafranski, Reference Gros, Pavlacic, Wray and Szafranski2023; Nepon, Belik, Bolton, & Sareen, Reference Nepon, Belik, Bolton and Sareen2010). A path analysis study involving 58 veterans with PD revealed that PD symptoms predicted agoraphobia symptoms, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms (Gros et al., Reference Gros, Pavlacic, Wray and Szafranski2023). Depressive symptoms subsequently predicted suicidal ideation (Gros et al., Reference Gros, Pavlacic, Wray and Szafranski2023). Brown et al. further reported that a panic-agoraphobic spectrum condition increased the risk of suicide attempts among patients with mood disorders (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Gaudiano and Miller2010). However, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions study of 34,653 adults discovered that only PD (with and without agoraphobia), but not agoraphobia without PD, was associated with an elevated risk of suicide attempts (Nepon et al., Reference Nepon, Belik, Bolton and Sareen2010). In the present study, we combined PD with agoraphobia and PD without agoraphobia into a single category and did not include patients with agoraphobia without PD. The complex associations between PD, agoraphobia, and suicide would need further investigation.

PD often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. In a nationwide population-based study conducted in Taiwan, Chen and Lin (Chen & Lin, Reference Chen and Lin2011) discovered that patients with PD were more likely to have MDD (OR = 23.45), bipolar disorder (OR = 15.54), and schizophrenia (OR = 2.14) compared with their healthy counterparts. Similarly, in the present study, we discovered that MDD was the most commonly observed psychiatric comorbidity (63.35%) in patients with PD, followed by bipolar disorder (8.93%), OCD (4.00%), SUD (3.55%), AUD (3.28%), and schizophrenia (3.06%). We also determined that patients with PD and MDD had a 6.08-fold higher rate of suicide compared with the control group, with only a 2.11-fold higher rate observed in those with PD but without MDD. Compared with the control group, women with PD and MDD exhibited an even higher (8.18-fold) risk of suicide. Several studies have indicated that, in patients with PD, MDD increases the risk of suicidality (Batinic, Opacic, Ignjatov, & Baldwin, Reference Batinic, Opacic, Ignjatov and Baldwin2017; Chen & Lin, Reference Chen and Lin2011). Tietbohl-Santos et al. (Tietbohl-Santos et al., Reference Tietbohl-Santos, Chiamenti, Librenza-Garcia, Cassidy, Zimerman, Manfro, Kapczinski and Passos2019) conducted a meta-analysis of risk factors for suicidality in patients with PD and reported that alcohol dependence and comorbid depression were associated with suicide attempts in patients with PD. In this study, we discovered that the rate of suicide was 2.99 times higher in patients with PD and AUD than in the control group and 1.73 times higher in patients with PD but without AUD than in the control group. Compared with the control group, women with PD and AUD exhibited an even higher (4.12-fold) risk of suicide.

Finally, the association between PD and suicidality may potentially be influenced by certain personality traits related to PD that do not exceed the clinical threshold to meet the diagnostic criteria of mental disorders (Bi et al., Reference Bi, Liu, Zhou, Fu, Qin and Wu2017; Peters, John, Bowen, Baetz, & Balbuena, Reference Peters, John, Bowen, Baetz and Balbuena2018). A study from the United Kingdom Biobank involving 389,365 adults aged 40–69 years indicated that neuroticism, frequently observed in individuals with PD, serves as a distal and non-specific risk factor for suicide (Peters et al., Reference Peters, John, Bowen, Baetz and Balbuena2018). The study demonstrated that neuroticism was associated with an increased risk of suicide in both men (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.15) and women (HR: 1.16) (Peters et al., Reference Peters, John, Bowen, Baetz and Balbuena2018). Bi et al. examined the personality traits among 196 people who attempted suicide and revealed that 156 individuals (79.6%) met the criteria for Axis I disorders (including PD) and 11 (6.6%) met the criteria for Axis II personality disorders using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV Axis I and II Disorders (Bi et al., Reference Bi, Liu, Zhou, Fu, Qin and Wu2017). Moreover, they found that individuals who attempted suicide and met the criteria for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders had higher neuroticism scores compared with those who attempted suicide without any DSM-IV Axis I or II Disorder diagnoses (Bi et al., Reference Bi, Liu, Zhou, Fu, Qin and Wu2017). Conversely, individuals who attempted suicide without any psychiatric disorder diagnoses exhibited higher impulsivity scores than those who attempted suicide and had a psychiatric disorder diagnosis (Bi et al., Reference Bi, Liu, Zhou, Fu, Qin and Wu2017). Further studies would clarify complex associations between PD, personality traits, and suicidality.

This study has some limitations. First, the number of suicide-related deaths may have been underestimated because some of these deaths may have been listed as deaths from accidents or unknown reasons in Taiwan’s national cause-of-death statistics. Nevertheless, because these statistics are compiled by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan, they are likely to be of high diagnostic validity. Second, we did not evaluate the severity of PD in this study. According to previous studies, the severity of panic attacks can be used as a predictor of suicidal behavior (Cox, Direnfeld, Swinson, & Norton, Reference Cox, Direnfeld, Swinson and Norton1994; Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Jones, Chernen and Barlow1992; Woodruff-Borden et al., Reference Woodruff-Borden, Stanley, Lister and Tabacchi1997). Third, patients with PD are likely to attempt suicide when they experience stressful life events (Scheer et al., Reference Scheer, Blanco, Olfson, Lemogne, Airagnes, Peyre, Limosin and Hoertel2020). Nevertheless, we were unable to determine the influence of environmental and psychological stressors because these variables were unavailable in our data. Fourth, the current study focused on Taiwanese individuals, potentially restricting its generalizability to other ethnic groups. Evidence suggested that there were differences in the patterns of PD/attacks among different races (Barrera, Wilson, & Norton, Reference Barrera, Wilson and Norton2010). For example, Asians were more likely to report symptoms such as dizziness, unsteadiness, choking, and feeling terrified compared with Caucasians (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wilson and Norton2010). In addition, Asians and Caucasians showed a greater association between panic symptoms and panic severity than did African Americans (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wilson and Norton2010). Further population-based studies specific to each race would be required to clarify this issue. Fifth, to ensure the diagnostic validity of PD, the present study only included those who had a PD diagnosis given by psychiatrists at least twice and excluded the subjects who were only diagnosed once. Finally, the development of the CCI relied on cancer epidemiological studies, potentially restricting its application to psychiatric epidemiological studies (Drosdowsky & Gough, Reference Drosdowsky and Gough2022). In addition, the mortality risk associated with an overall multimorbidity index may differ from that of a specific disease. In the present study, we focused on an association between PD and suicide after adjusting for CCI scores. Further studies may be required to clarify specific physical comorbidity with PD-related suicide risk.

In conclusion, patients with PD have a high rate of suicide mortality. PD alone is associated with a relatively low but significant risk of suicide mortality. In patients with PD, suicide mortality may be exacerbated by psychiatric comorbidities, particularly MDD, autism, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, AUD, and SUD. Therefore, clinicians should carefully monitor the mental health and suicide potential of patients with PD, particularly those with major psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, future studies should focus on the complex interplay between neurobiological factors, chronic stress, impaired functioning, and comorbid mental health conditions, which increase the risk of suicide among patients with PD. Addressing these concerns through comprehensive treatment approaches, including psychotherapy and medication, can mitigate this risk and improve the overall mental health outcomes of these patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724003441.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr I-Fan Hu for his support and friendship.

Author contribution

Drs MHC and SJT designed the study; Drs MHC and CMC and Ms WHC analyzed the data; Drs MHC and SJT drafted the manuscript; Drs TPS, YMB, and TJC performed the literature reviews; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and agreed to its publication.

Funding source

The study was supported by grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V113C-039, V113C-011, V113C-010, V114C-089, V114C-064, V114C-217), Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-113-32, CI-113-30, CI-114-35), Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST111-2314-B-075-014-MY2, MOST 111-2314-B-075-013, NSTC113-2314-B-075-042), Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, Academia Sinica Joint Research Program (VTA112-V1-6-1, VTA114-V1-4-1) and Veterans General Hospitals and University System of Taiwan Joint Research Program (VGHUST112-G1-8-1, VGHUST114-G1-9-1), Cheng Hsin General Hospital (CY11402-1, CY11402-2). The funding source had no role in any process of our study.

Financial disclosure

All authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Competing interest

No conflict of interest.