Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is the largest threat to the world in this century (WHO, 2020). To limit transmission, business and school closures are implemented, mass quarantines (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020) are imposed and self-isolation and social distancing (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Trumble, Stieglitz, Mamany, Cayuba, Moye and Gurven2020) are highly recommended, and such measures have been implemented in almost all countries to differing extents (Galea, Merchant, & Lurie, Reference Galea, Merchant and Lurie2020; Ho, Chee, & Ho, Reference Ho, Chee and Ho2020; Jung & Jun, Reference Jung and Jun2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b). Millions of people in the world have been infected, with ever increasing numbers under quarantine or in isolation. Fear of illness, severe shortages of resources, social isolation, large and growing financial losses, and increased uncertainty will contribute to widespread psychological distress and increased risk for mental illness and behavioral disorders as a consequence of COVID-19 (Pfefferbaum & North, Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020).

The worldwide impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health has already been identified as including insomnia, anxiety, and depression among healthcare workers and other vulnerable populations (Que et al., Reference Que, Shi, Deng, Liu, Zhang, Wu and Lu2020; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Hu, Hu, Jin, Wang, Xie and Xu2020; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Fang, Hou, Han, Xu, Dong and Zheng2020; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zheng, Jia, Chen, Mao, Chen and Dai2020; Gonzalez-Sanguino et al., Reference Gonzalez-Sanguino, Ausin, Castellanos, Saiz, Lopez-Gomez, Ugidos and Munoz2020; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault and Bullmore2020; King, Delfabbro, Billieux, & Potenza, Reference King, Delfabbro, Billieux and Potenza2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Lu, Que, Huang, Liu, Ran and Lu2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Gauthier, Yu, Tang, Barbarino and Yu2020a, Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020b, Reference Wang, Zhao, Feng, Liu, Yao and Shi2020c; Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li, & Yang, Reference Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li and Yang2020). Chinese healthcare workers exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic reported symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34.0%), and psychological distress (71.5%) (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei and Hu2020). These symptoms also manifest in the general population, whose prevalence of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and acute stress was 27.9, 31.6, 29.2, and 24.4%, respectively (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Lu, Que, Huang, Liu, Ran and Lu2020). Similar types of symptoms have accompanied other infectious disease epidemics such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS), and Ebola virus disease (EVD) (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chee and Ho2020; Jalloh et al., Reference Jalloh, Li, Bunnell, Ethier, O'Leary, Hageman and Redd2018; Pfefferbaum & North, Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020; Vyas, Delaney, Webb-Murphy, & Johnston, Reference Vyas, Delaney, Webb-Murphy and Johnston2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fang, Guan, Fan, Kong, Yao and Hoven2009). People discharged from hospital after recovering from COVID-19 have reported high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bo et al., Reference Bo, Li, Yang, Wang, Zhang, Cheung and Xiang2020). A systematic review showed that after severe coronavirus infection, the point prevalence of PTSD was 32.2% (95% CI 23.7–42.0), depression was 14.9% (12.1–18.2), and anxiety was 14.8% (11.1–19.4) (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, McGuire, Fusar-Poli and David2020). Some mental health problems persisted for years with a quarter of SARS patients having PTSD, and 15.6% having depression 2 years after experiencing SARS (Mak, Chu, Pan, Yiu, & Chan, Reference Mak, Chu, Pan, Yiu and Chan2009).

Early detection and recognition of COVID-19-related psychiatric symptoms is pivotal for tailoring cost-effective accessible interventions. Mental health responses could enhance coping and lead to recovery from this massive worldwide psychological trauma of COVID-19 and the pandemic. Given the developing situation with coronavirus pandemic worldwide, policy makers urgently need an evidence synthesis to produce guidance for the development of psychological interventions and mental health response. The aim of this paper is to synthesize the data on mental health services and interventions for the infectious disease epidemics, and to enhance knowledge and improve the quality and effectiveness of the mental health response to COVID-19 and future infectious disease epidemics.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We sought to include any articles focusing on mental health interventions or services applied specifically for infectious disease outbreaks. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, PsycINFO on 5 May 2020, using a combination of text words and MeSH terms: (SARS OR severe acute respiratory syndrome OR Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus OR middle east respiratory syndrome* OR MERS-CoV OR Mers OR Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome* OR MERSCoV* OR coronavirus OR coronavirus infections OR coronavirus* OR COVID-19 OR 2019-nCoV OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Ebola) AND (mental disorders OR mental health OR mental health programs OR mental health services OR public health services OR emergency services psychiatric OR emotional trauma OR psychosocial interventions OR psychiatric interventions OR psychological treatment OR psychotherapy). We also searched WHO Global Research Database on COVID-19 using the term ‘mental health’, and the preprint server medRxiv with search terms ‘SARS or MERS or Ebola or coronavirus or COVID-19’ and ‘mental health’ on 15 April 2020. Articles about mental health services (e.g. mental health system, mental health measures or strategies) and specific types of psychological interventions for infectious diseases such as SARS, MERS, EVD, and COVID-19 were included in the present review. We excluded articles on the epidemiology of psychological impacts, mental health responses to other types of diseases, and non-English publications.

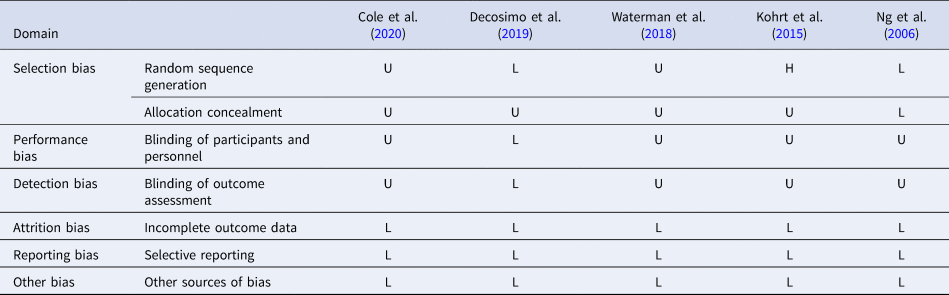

All articles were independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers (SYK and YW) on title and abstract. All full-text articles identified were reviewed by YJL and BYP. For each retrieved full-text article, we hand searched the article's references and examined possible additional studies. Original intervention trials were independently critically appraised using the Cochrane Collaboration's quality assessment tool by two reviewers (SSZ and YK) (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher, Oxman and Sterne2011; Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2009). Consensus was used to resolve any disagreements. Review authors’ judgments evaluated selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. In all cases, an answer ‘L’ indicates a low risk of bias and an answer ‘H’ indicates high risk of bias. If insufficient detail was reported of what happened in the study, the judgment will usually be ‘Unclear’ risk of bias.

Results

Search retrieval and characteristics

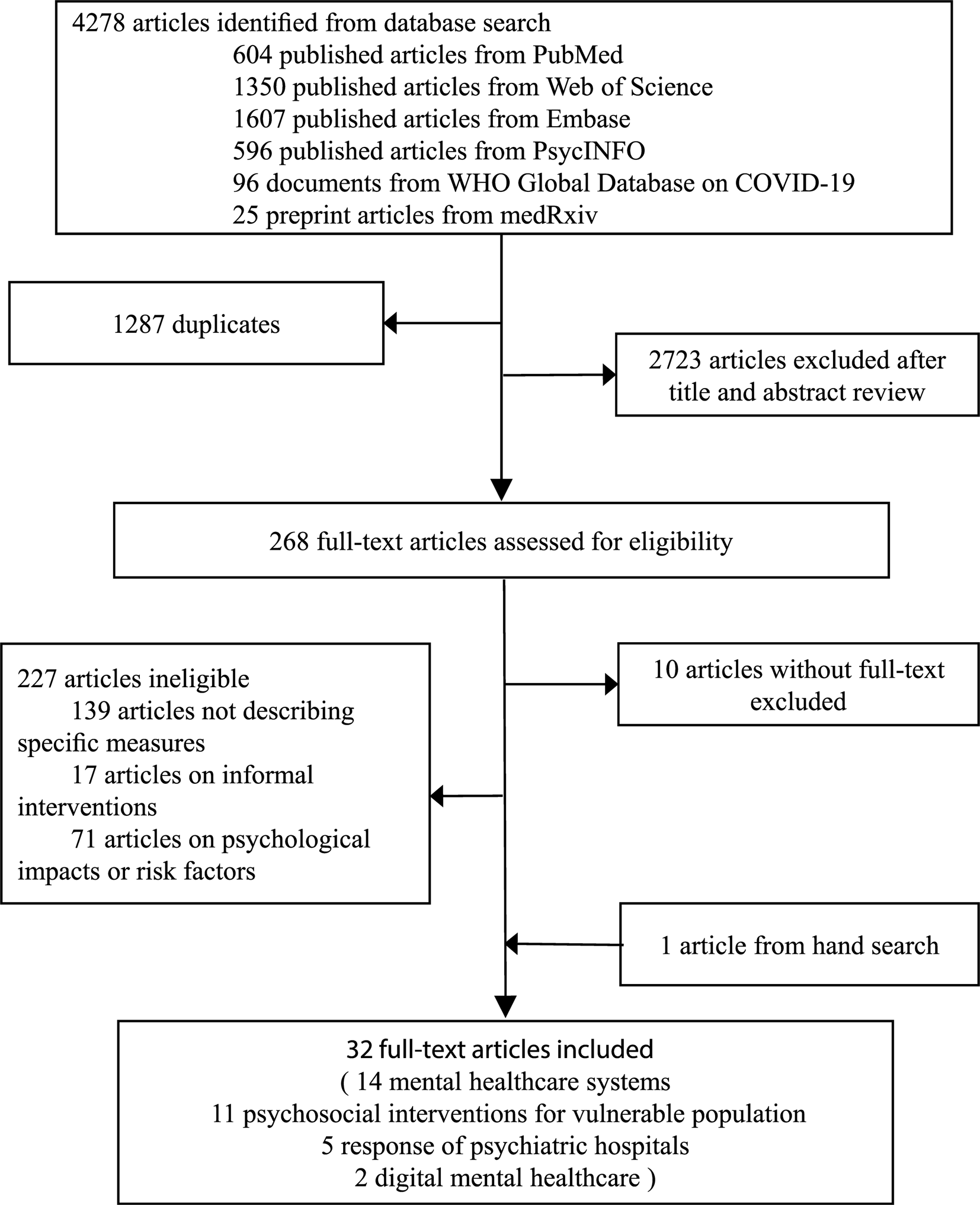

The PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and PsycINFO search identified 604, 1350, 1607, and 596 articles, respectively. The WHO Global Research Database on COVID-19 identified 96 articles and medRxiv identified 25 articles. There were 2723 articles left after removing those articles which were duplicates from the six searches. Hand searching of full-text articles yielded one additional reference to include in this review. In total, 32 eligible articles were included in this review (see Fig. 1), most focusing on COVID-19, followed by EVD, SARS, and MERS. Of the 32 articles, one used a randomized controlled trial (RCT), seven used quasi-experimental methods or pre-post intervention or quantitative interview, 24 reported processes of the delivery of care but did not rigorously evaluate outcomes (8 reports, 14 commentaries, and 2 reviews) (see Table 1). Twenty-three articles described mental health practices and services for COVID-19 [China (9), South Korea (2), Singapore (2), Italy (2), and one each for Canada, Germany, USA, UK, Malaysia, Iran, Australia, and Spain], seven articles for EVD [Sierra Leone (5), Liberia (1), and USA (1)], one article for SARS (Hong Kong, China), and one article for MERS (South Korea).

Fig. 1. Selection of included studies.

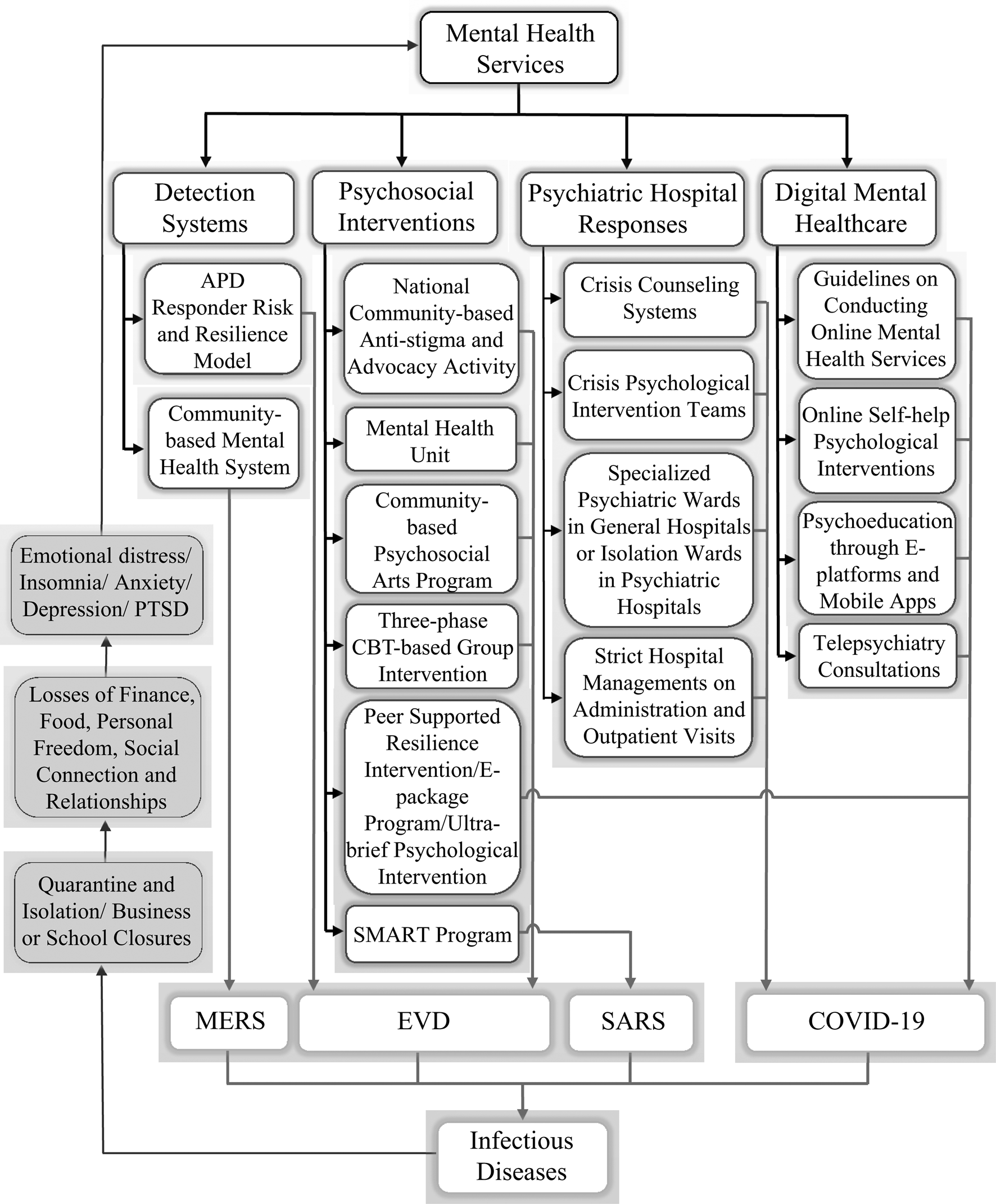

Table 1. Characteristics and main results of articles included in the systematic review

AI, artificial intelligence; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CBT-I, cognitive behavioral therapy of insomnia; CIT, crisis intervention team; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ETC, Ebola treatment center; EVD, Ebola virus disease; IMH, Institute of Mental Health; MERS, middle east respiratory syndrome; MHCs, mental health clinicians; MHPSS, mental health and psychosocial support; NHC, National Health Center; PFA, psychological first aid; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

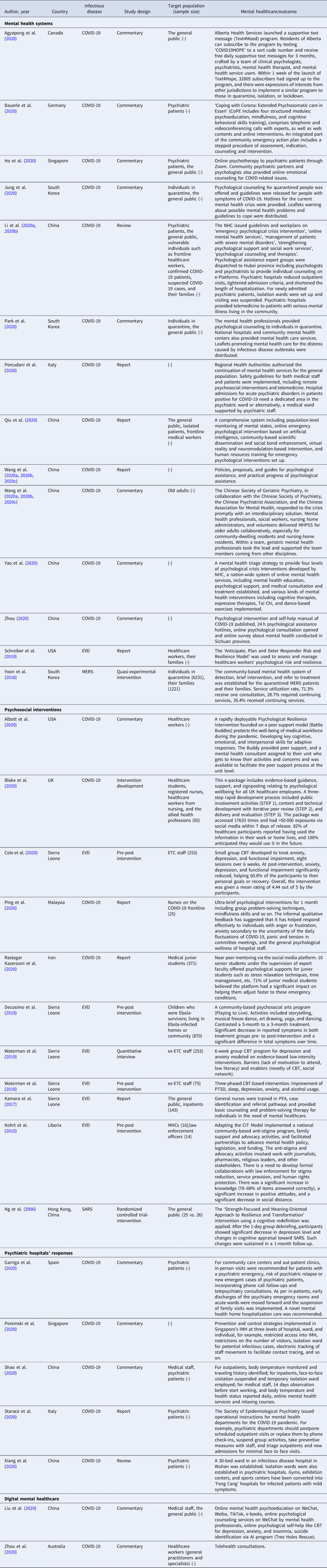

Four different mental health practices were reported in this systematic review, including mental healthcare systems, psychosocial interventions, specific responses of psychiatric hospitals and digital mental healthcare (see Fig. 2). Fourteen articles described mental healthcare systems, six in China (all for COVID-19), three in South Korea (2 for COVID-19 and 1 for MERS), one each for COVID-19 in Canada, Germany, Singapore, Italy, and one for EVD in the USA. Eleven articles evaluated psychosocial interventions (5 for EVD in Sierra Leone, 1 for EVD in Liberia, 1 for SARS in Hong Kong China and 1 each for COVID-19 in the USA, UK, Malaysia, and Iran). Five articles described the response of psychiatric hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic [China (2), Spain (1), Singapore (1), and Italy (1)]. Two articles reported the digital mental healthcare for the COVID-19 outbreak [China (1) and Australia (1)]. Multiple vulnerable populations were the main target subjects including healthcare workers, psychiatric patients, quarantined individuals, family members, older adults, and children (see Table 1).

Fig. 2. Summary of mental health interventions during infectious disease outbreaks.

Quality appraisal

Table 2 summarizes the assessment of risk of bias for five controlled trials. The majority of the intervention trials showed a low risk of bias, or we were unable to determine the risk. One trial had low risk of performance bias and detection bias, one trial had high risk of selection bias, and we were unable to determine the risk for other trials. All five trials had low risk of attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases. As the other 27 records included in this review were not controlled trials or were commentaries, we did not conduct quality assessments for them.

Table 2. Risk of bias summary showing review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias domain

L, low risk; H, high risk; U, unable to determine.

Mental health intervention systems for infectious disease outbreaks

Governments have variously developed interventions and response systems to deal with the mental health problems caused by emergency infectious disease epidemic. Countries including China, South Korea, Singapore, and Canada had experienced SARS and MERS outbreaks, which brought them evidence-based experience to better cope with the mental health crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the MERS outbreak, the South Korean government established a community-based mental health system for detection, brief intervention, and referral of treatment for the MERS patients and their families quarantined in Gyeonggi province (Yoon, Kim, Ko, & Lee, Reference Yoon, Kim, Ko and Lee2016). Various mental health centers such as public health centers, community mental health centers cooperatively delivered services for MERS patients and the National Center for Crisis Mental Health Management evaluated people using these services and subsequently transferred them to local community mental health centers for continuing case management and follow-up. The service utilization rate was high, but they also found that the referral system from the national level to regional or local levels did not work well (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Kim, Ko and Lee2016). While active detection of subjects with emotional difficulties and interventions following the COVID-19 outbreak was a potential option, they needed a more efficient process for an open entry system at the local level rather than a triage system starting nationally from the top.

A series of mental health-related actions were taken at the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China (Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b; Qiu, Zhou, Liu, & Yuan, Reference Qiu, Zhou, Liu and Yuan2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Gauthier, Yu, Tang, Barbarino and Yu2020a, Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020b, Reference Wang, Zhao, Feng, Liu, Yao and Shi2020c; Yao, Chen, Zhao et al., Reference Yao, Chen, Zhao, Qiu, Koenen, Stewart and Xu2020; Zhou, Reference Zhou2020), Singapore (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chee and Ho2020), South Korea (Jung & Jun, Reference Jung and Jun2020; Park & Park, Reference Park and Park2020; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Kim, Ko and Lee2016), Canada (Agyapong, Reference Agyapong2020), Germany (Bauerle, Skoda, Dorrie, Bottcher, & Teufel, Reference Bauerle, Skoda, Dorrie, Bottcher and Teufel2020), Italy (Percudani, Corradin, Moreno, Indelicato, & Vita, Reference Percudani, Corradin, Moreno, Indelicato and Vita2020), and the USA (Schreiber, Cates, Formanski, & King, Reference Schreiber, Cates, Formanski and King2019). Specifically, mental health professionals including psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, and psychologists were deployed to provide psychological counseling and support for vulnerable populations (e.g. frontline healthcare workers, confirmed COVID-19 patients, suspected COVID-19 cases and their families) in China and for people in quarantine in South Korea. The National Health Center of China (NHC) issued several guidelines and plans (NHC-China, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d, 2020e, 2020g). Several national associations related to mental health and academic societies cooperated to establish expert groups on psychological interventions to older adults (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Gauthier, Yu, Tang, Barbarino and Yu2020a, Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020b, Reference Wang, Zhao, Feng, Liu, Yao and Shi2020c). Psychoeducational books, articles, and videos were made available for the public through e-platforms and mobile apps (e.g. WeChat) at the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in China (Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi, & Lu, Reference Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi and Lu2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b; Pfefferbaum et al., Reference Pfefferbaum, Flynn, Schonfeld, Brown, Jacobs, Dodgen and Lindley2012).

Several hospitals, individual psychiatric departments, community psychiatric partners, and psychologists all provided online psychotherapy and counseling to psychiatric patients and the general public with COVID-related psychological distress through videoconferencing platforms (e.g. Zoom) in Singapore (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chee and Ho2020). Leaflets for the general public provided guidelines for coping with the COVID-19 distress and hotlines provided information for COVID-19 mental health crisis that might occur in South Korea (Park & Park, Reference Park and Park2020). Canada launched a support text message (Text4Mood) program to respond to the psychological impact of COVID-19. This program provided free psychological supportive text messages daily for 3 months (Agyapong, Reference Agyapong2020). Germany's ‘Coping with Corona: Extended Psychosomatic care in Essen’ (CoPE) offered psychological support for distressed individuals, which included four steps: initial contact, triage and diagnosis, support via tele- or video-conference, and aftercare. This program offered psycho-educational information materials about resources, relaxation techniques, and mental health (Bauerle et al., Reference Bauerle, Skoda, Dorrie, Bottcher and Teufel2020).

Increasing public mental health literacy is vital to prevent and overcome the mental health crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education and support from the voluntary and professional mental health sectors should be a part of mental health prevention under large infectious disease outbreaks.

Psychosocial interventions for specific populations during infectious disease outbreaks

Psychological and physical supports tended to be specifically matched to different vulnerable populations, such as children, older adults, and health care workers.

For individuals with mental health needs

A national community-based anti-stigma and advocacy activity, which is a curriculum based upon the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model was launched in Liberia during the EVD outbreak, could significantly decrease mental health and public health problems including violence, self-harm and suicide (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Blasingame, Compton, Dakana, Dossen, Lang and Cooper2015). A mental health unit was created at Connaught hospital in Sierra Leone during EVD outbreak (Kamara et al., Reference Kamara, Walder, Duncan, Kabbedijk, Hughes and Muana2017). General nurses were trained in psychological first aid (PFA), case identification, and referral pathways, and provided basic counseling and problem-solving therapy for individuals with mental healthcare needs. A nurse-led approach within a non-specialist setting appears to have been successful for delivering mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) services during the EVD outbreak. Peer support programs or services led by non-professional mental health workers are potential ways to deliver care in areas with limited human resources and weak social welfare systems.

An alternate strategy which was employed during the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Chan, Chan, Lee, Yau, Chan and Lau2006) was the Strength-Focused and Meaning-Oriented Approach to Resilience and Transformation (SMART). This intervention employed a body-mind-spirit framework with a strong emphasis on cognitive redefinition of the stressful situation and the individual's response. Results of the RCT (n = 51) suggested that participants’ depression levels and adaptive changes in cognitive appraisal of SARS decreased significantly after the single-day group debriefing. As this intervention trial included only a small sample, its efficacy needs to be replicated in a larger sample, and should include a follow-up study.

For children and adolescents

A community-based psychosocial arts program created by Playing to Live (PTL) was established for children who were Ebola-survivors or living in Ebola-affected homes or communities (Decosimo, Hanson, Quinn, Badu, & Smith, Reference Decosimo, Hanson, Quinn, Badu and Smith2019). The PTL group hired and trained 40 Ebola-survivors to run the PTL activities two to three times a week in their communities. They also hired 40 psychosocial workers to provide weekly supportive talks to families, and information about childcare and child rights. The PTL activities included storytelling, musical freeze dance, art drawings, yoga, and dancing. Results of the pre-post-evaluation (n = 870) suggested that the 3-month program was associated with a 15% reduction in symptoms including social withdrawal, extreme anger, bedwetting, worry/anxiety, poor eating habits, violence, and continued sadness, whereas the 5-month intervention group showed a 38% reduction of such symptoms.

For older adults

For mental disorders of old age, particularly dementia, there have been limited reports of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found only one report on mental health care for older adults among our included papers. Given the high death rate among older adults infected with COVID-19 and the added strain on families with older relatives and on the institutions caring for them, the Chinese Society of Geriatric Psychiatry in collaboration with the Chinese Society of Psychiatry responded with an interdisciplinary solution. Mental health professionals, social workers, nursing home administrators, and volunteers collaboratively delivered MHPSS for older adults, especially for community-dwelling residents and nursing-home residents (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Gauthier, Yu, Tang, Barbarino and Yu2020a, Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020b, Reference Wang, Zhao, Feng, Liu, Yao and Shi2020c). Mental health care for older adults during this epidemic was not given enough attention in the early stage of outbreak. More specific age-appropriate interventions may need to be developed for older adults for effective intervention during pandemic in the future.

For healthcare workers

Frontline health care workers are also shouldering a greater mental health burden, and thus need support in strengthening their resilience through peer support and other interventions (Que et al., Reference Que, Shi, Deng, Liu, Zhang, Wu and Lu2020). First, proper protection against their own infection is critical. For example, masks, personal protective equipment, and other essential medical equipment (e.g. ventilators) will help relieve the stress of having to treat people with infections, and improve their mental wellbeing. During this COVID-19 crisis, various interventions were offered to healthcare workers, such as a peer-supported resilience intervention in the USA (Albott et al., Reference Albott, Wozniak, McGlinch, Wall, Gold and Vinogradov2020), e-package with Agile methodology in the UK (Blake, Bermingham, Johnson, & Tabner, Reference Blake, Bermingham, Johnson and Tabner2020), and the ultra-brief psychological intervention in Malaysia (Ping et al., Reference Ping, Shoesmith, James, Nor Hadi, Yau and Lin2020). The e-package in the UK included evidence-based guidance, support, and signposting relating to psychological wellbeing, and results of this pre-post intervention (n = 55) revealed that 82% of healthcare participants used the information in their work or home lives (Blake et al., Reference Blake, Bermingham, Johnson and Tabner2020). Feedback from healthcare workers suggests that qualitative wellness is improved by providing a free online resource manual targeting psychological skills and interventions to reduce the distress caused by uncertainty during the pandemic (Ping et al., Reference Ping, Shoesmith, James, Nor Hadi, Yau and Lin2020). Many countries have developed dedicated teams to provide mental health support for healthcare workers; however, the type of support needed depends on the stage of the pandemic, and can benefit from peer and professional counseling (Isaksson Rø, Veggeland, & Aasland, Reference Isaksson Rø, Veggeland and & Aasland2016).

The Anticipate, Plan, and Deter responder risk and resilience model was used to assess and manage healthcare workers’ psychological risk and resilience during the EVD outbreak (Schreiber et al., 2019). The Anticipate, Plan, and Deter model contains three components. First, pre-deployment training about the stressors that healthcare workers may face during deployment (‘Anticipate’). Second, development of a personal resilience plan (‘Plan’) and monitoring stress exposure during deployment using the web-based system. Third, invoking the personal resilience plan when risk is elevated (‘Deter’), addressing responder risk early before the onset of impairment. Psychological support was offered to junior medical students in Iran via a novel social media platform during the COVID-19 (Rastegar Kazerooni, Amini, Tabari, & Moosavi, 2020). In total, 71% of participants (n = 371) believed the platform had a significant impact on helping them adjust faster to these emergency conditions.

Following the EVD outbreak in Sierra Leone, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) was widely used among Ebola treatment center (ETC) staff (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Waterman, Hunter, Bell, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2020; Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018; Waterman, Cole, Greenberg, Rubin, & Beck, Reference Waterman, Cole, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2019). Results of the pre-post intervention (n = 253) showed that small group CBT could significantly reduce anxiety, depression, and functional impairment of ETC staff after eight sessions over 6 weeks (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Waterman, Hunter, Bell, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2020). Workshops with different themes such as PFA, stress, sleep, depression, anxiety, relationships, and behavior were developed in phase 1 and 2. Participants still displaying high anxiety and depression levels after phase 1 and 2 were enrolled in phase 3 with low-intensity CBT strategies. Significant improvements in the stress, anxiety, depression, and anger domains were reported, but no improvement in sleep (Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018). CBT is an evidence-based intervention delivered through various means besides face-to-face interactions. For example, delivery over the Internet or smartphone apps can be efficient for broad outreach to the populations at risk for mental health complications. The feasibility and effectiveness of training a national team to deliver a three-phase CBT-based group intervention to ex-ETC staff suggested that this model protected healthcare workers from negative psychological consequences of potentially traumatic stressors (Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018; Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Cole, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2019). However, the effectiveness of this model and its components needs more rigorous evaluation, because it relied on a single small sample during a unique epidemic (Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Cates, Formanski and King2019). Furthermore, most of the reviewed studies were pre-post measurements with substantial heterogeneity in the included participants, methods, study designs, and outcomes. Standardized evaluations in randomized clinical trials were difficult to implement due to the urgent nature of the pandemics. Evidence-based interventions that have shown efficacy in conditions differing from epidemics also might be effective approaches to combat COVID-19, but their effectiveness needs to be tested in controlled trials during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Psychiatric hospitals’ response for infectious disease outbreaks: focus on COVID-19

Psychiatric hospitals in China prepared to cope with the COVID-19 outbreak by establishing crisis psychological intervention teams across many psychiatric hospitals, including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatric nurses (Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b; Shao, Shao, & Fei, Reference Shao, Shao and Fei2020; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Zhao, Liu, Li, Zhao, Cheung and Ng2020). A specialized psychiatric ward was established in an infectious disease hospital in Wuhan on 3 February 2020, and in turn isolation wards were established in psychiatric hospitals for mentally ill patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Zhao, Liu, Li, Zhao, Cheung and Ng2020). NHC issued a set of guidelines in February 2020 to standardize the management of patients with severe mental disorders during the COVID-19 outbreak (NHC-China, 2020f). Subsequently, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry published guidelines to the hospital administration applicable to both psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units in general hospitals during the outbreak (Chinese Society of Psychiatry, 2020). Psychiatric hospitals reduced outpatient visits, tightened admission criteria, and shortened the length of inpatient hospitalizations. For newly admitted psychiatric patients, isolation wards were set up and visiting was suspended to minimize the potential risk of nosocomial infection. Additionally, the majority of psychiatric hospitals used telemedicine to provide psychiatric consultations for infected patients and medical treatments for patients with preexisting mental disorders, and antipsychotic drugs were often delivered to patients’ homes following the COVID-19 outbreak in China.

The Italian Society of Epidemiological Psychiatry also issued operational instructions for the management of mental health departments and similar measures were employed in Italy (Starace & Ferrara, Reference Starace and Ferrara2020). The Institute of Mental Health (IMH) in Singapore implemented a series of prevention and control strategies at the levels of hospital, ward, and individual (Poremski et al., Reference Poremski, Subner, Lam, Kin, Dev, Mok and Fung2020). Except for restrictions on patients and visitors, medical staff were managed effectively, for example, electronic tracking of staff movement to facilitate contact tracing in Singapore (Poremski et al., Reference Poremski, Subner, Lam, Kin, Dev, Mok and Fung2020) and China (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Shao and Fei2020). For community care centers and out-patient clinics, in-person visits were recommended for patients with a psychiatric emergency, risk of psychiatric relapse or new emergent cases with mental disorders, incorporating phone call follow-ups and telepsychiatry consultations in Spain (Garriga et al., Reference Garriga, Agasi, Fedida, Pinzón-Espinosa, Vazquez, Pacchiarotti and Vieta2020). As per in-patients, early discharges of the psychiatry emergency rooms and acute wards were moved forward and the suspension of family visits was implemented. A novel mental health home hospitalization care was recommended (Garriga et al., Reference Garriga, Agasi, Fedida, Pinzón-Espinosa, Vazquez, Pacchiarotti and Vieta2020).

The infection control measures needed to limit potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 led to inaccessibility of some mental health interventions such as injectable medications and electroconvulsive therapy, and the relative risks and benefits of these treatment losses need to be evaluated (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley, Jones and Arango2020). These losses should be assessed in the balance with many novel strategies involving digital telemedicine, mental health home hospitalization, commercial drug delivery, and electronic tracking. Moreover, follow-up studies are needed on how effective these interventions were in mitigating the mental health impacts of other losses to mental services and patients.

Digital mental healthcare for infectious disease outbreaks, particularly for COVID-19

Tele-mental health services were prioritized for individuals at higher risk of exposure to COVID-19 infection such as frontline clinicians, infected patients, suspected cases of infection, their families, and policemen. There are well-documented reports of China proactively providing various tele-mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Zhang, Xiang, Liu, Hu and Zhang2020; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Snoswell, Harding, Bambling, Edirippulige, Bai and Smith2020). The NHC and the Chinese Psychological Society provided guidelines on conducting online mental health services (Li et al., Reference Li, Yang, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Zhang and Xiang2020a, Reference Li, Yang, Qiu, Wang, Jian, Ji and Li2020b; NHC-China, 2020a, 2020e). These services were provided by the government, academic agencies (e.g. hospitals, universities, institutes), associations of mental health professionals, and non-government organizations. The services included counseling, supervision, training, as well as psychoeducation through e-platforms (e.g. hotline, WeChat, Weibo, Tencent QQ, Alihealth, and HaoDaiFu) (MOE-China, 2020). Additionally, online self-help psychological interventions such as CBT for depression, anxiety, and insomnia were also developed (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Zhang, Xiang, Liu, Hu and Zhang2020). Early reports indicated high interest and acceptance of these services by the target population. The ‘National Crisis Intervention Platform for COVID-19’ was created with mental health professionals. Several hospitals set up their own crisis counseling system for staff and patients using telehealth in many provinces of China (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liang, Li, Guo, Fei, Wang and Zhang2020; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Li, Hu, Chen, Yang, Yang and Liu2020). The Australian government had delivered a wide range of telehealth services including telehealth consultations to general practitioners and specialists (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Snoswell, Harding, Bambling, Edirippulige, Bai and Smith2020). However, to date, the Australian government has focused on managing the physical health needs of the population during the epidemic, with less focus on mental health (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Snoswell, Harding, Bambling, Edirippulige, Bai and Smith2020). Access to other existing tele-mental health support services such as self-help platforms, videoconferencing, or mobile apps for depression, anxiety, and emotional problems should be made available for the general population (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Snoswell, Harding, Bambling, Edirippulige, Bai and Smith2020).

Telehealth has become a cost-effective alternative for delivering mental health care during the COVID-19 global pandemic when in person and face-to-face visits are not possible. Solid evidence supports the effectiveness of telephone and web-based interventions, especially for alleviating symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Kerst, Zielasek, & Gaebel, Reference Kerst, Zielasek and Gaebel2020; Turgoose, Ashwick, & Murphy, Reference Turgoose, Ashwick and Murphy2018). Videoconferencing, online programs, smartphone apps, text-messaging, and e-mails have been useful communication methods for the delivery of mental health services (Torniainen-Holm et al., Reference Torniainen-Holm, Pankakoski, Lehto, Saarelma, Mustonen, Joutsenniemi and Suvisaari2016; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Snoswell, Harding, Bambling, Edirippulige, Bai and Smith2020). National and provincial digital mental health services (e.g. hotlines, websites, WeChat, Weibo) have been established as essential measures to address mental health needs of key target populations such as healthcare providers during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, digital therapies might not be appropriate for older or demented people, people with reading difficulties, poor people, or people who are not technologically adept. The combination of online and offline psychological counseling is a key strategy for mental health services and intervention systems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

This paper provides a rapid review of the published literature on mental health practices and services during recent infectious disease epidemics. Except for publications on some mental health intervention systems and psychosocial interventions, most other reports were not specifically designed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of mental health interventions. More evidence-based psychosocial interventions with telehealth services and considering contextual adaptation, complexity, and resources requirements are needed during the COVID-19 pandemic and future outbreaks of infectious diseases.

During infectious disease outbreaks such as COVID-19, measures implemented for their prevention (e.g. quarantine and isolation, business or school closures) as well as the losses induced by them (e.g. finance, food, personal freedom, social connection, and relationships) contributed to significant emotional distress, reduced mental well-being, and may lead to psychiatric or behavioral disorders in both the short and long term. These consequences are of sufficient magnitude, requiring immediate efforts and direct interventions to reduce the impact of the outbreaks at both individual and population levels (Galea et al., Reference Galea, Merchant and Lurie2020). Psychoeducation and emotional support in particular help to normalize crisis reaction, mobilize resources, and increase adaptive coping strategies for progression to serious mental illness such as major depression or PTSD (North & Pfefferbaum, Reference North and Pfefferbaum2002; North, Hong, & Pfefferbaum, Reference North, Hong and Pfefferbaum2008; Reyes, Reference Reyes and Elhai2004). However, many countries have tended to focus on the physical health needs of COVID-19, often neglecting mental health needs with few designated organizations offering specific mental health services with easy access to those in need. The integration of mental health provisions into the COVID-19 (and other infectious disease emergencies) response should be best addressed at the national, state, and local planning levels (Pfefferbaum & North, Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020).

Call for evidence-based psychosocial interventions to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic

Prevention efforts in mental health were implemented primarily for people who were at risk or had greater vulnerability, such as frontline workers, confirmed COVID-19 patients, infected family members, and those affected by the loss of loved ones (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault and Bullmore2020). MHPSS programs through international organizations were used effectively in several low- and middle-income countries during infectious disease outbreaks (Cenat et al., Reference Cenat, Mukunzi, Noorishad, Rousseau, Derivois and Bukaka2020). For example, group-based CBT (Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Hunter, Cole, Evans, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2018; Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Cole, Greenberg, Rubin and Beck2019), PFA, PTL (Decosimo et al., Reference Decosimo, Hanson, Quinn, Badu and Smith2019), culturally adapted interventions such as SMART (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Chan, Chan, Lee, Yau, Chan and Lau2006), ultra-brief psychological interventions (Ping et al., Reference Ping, Shoesmith, James, Nor Hadi, Yau and Lin2020) and peer supports (Rastegar Kazerooni et al., Reference Rastegar Kazerooni, Amini, Tabari and Moosavi2020) have been reported to effectively mitigate the emotional impacts of COVID-19, EVD, and SARS outbreaks. However, the quality of evidence was still restricted because limited studies have provided quantitative data, and most intervention studies included small numbers of participants.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, other evidence-based interventions can be applied, and their feasibility and effectiveness should be evaluated. For example, mindfulness-based interventions (Hofmann & Gomez, Reference Hofmann and Gomez2017) or CBT for insomnia (Koffel, Bramoweth, & Ulmer, Reference Koffel, Bramoweth and Ulmer2018; Riemann et al., Reference Riemann, Baglioni, Bassetti, Bjorvatn, Dolenc Groselj, Ellis and Spiegelhalder2017; Trauer, Qian, Doyle, Rajaratnam, & Cunnington, Reference Trauer, Qian, Doyle, Rajaratnam and Cunnington2015) can be assessed for their effectiveness in the provision for individuals suffering from severe sleep problems or chronic anxiety symptoms. Psychosocial interventions can provide support for individuals in the wake of a crisis and can increase the perceived safety of individuals, further ameliorating maladaptive stress reactions and reducing emotional distress (Slavich, Reference Slavich2020). People with major losses or those with more severe illnesses are more vulnerable to experience depression, suicidal ideation, or PTSD in the initial phase of the pandemic or even after it ends (North, Suris, Davis, & Smith, Reference North, Suris, Davis and Smith2009). Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapies and pharmacotherapy are appropriate. For specific subgroups, family intervention may be recommended (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015; Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Creamer, Bisson, Cohen, Crow, Foa and Ursano2010; North & Pfefferbaum, Reference North and Pfefferbaum2013). Facing the pandemic, measures for identifying, triaging, referring, and treating severe psychosocial consequences, death notification, and bereavement care should be established (North & Pfefferbaum, Reference North and Pfefferbaum2013; Pfefferbaum & North, Reference Pfefferbaum and North2020; Sun, Bao, & Lu, Reference Sun, Li, Bao, Meng, Sun, Schumann and Shi2020). Moreover, for the lower income countries, with greater scarcity of mental health resources, implementation or modification of evidence-based psychological treatments, such as psychological treatments to be delivered by non-specialist providers including through task sharing, is urgently needed (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon and Thornicroft2020; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017).

Evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to mitigate COVID-19's mental health consequences on patients

The degree of risk for infection with COVID-19 for individuals with severe mental illnesses has not been clearly established; however, it is reasonable to presume such risk to be higher than that of the general population, because of disordered mental state, possible poor self-care, inadequate insight, or side effects of psychotropic medications (Starace & Ferrara, Reference Starace and Ferrara2020; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Zhao, Liu, Li, Zhao, Cheung and Ng2020). Furthermore, adverse social determinants brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, including poverty, food insecurity, and stigma, can be contributory (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Saxena2018). People with severe mental health problems commonly live in poverty which impacts their ability to socially distance themselves from neighbors or the local community and increases transmission risk. Psychiatric inpatients confirmed or suspected COVID-19 could be treated in specialized wards in infectious disease hospitals or in isolated wards in psychiatric hospitals or shelter hospitals equipped with psychiatric consultations. As for psychiatric hospitals, measures including strict triaging/precautionary procedures and admission criteria, and shorter hospitalization length of stay should be taken to prevent the clustering of COVID-19 cases (Chinese Society of Psychiatry, 2020; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Shao and Fei2020; Starace & Ferrara, Reference Starace and Ferrara2020). Additionally, mental health home hospitalization care was recommended (Garriga et al., Reference Garriga, Agasi, Fedida, Pinzón-Espinosa, Vazquez, Pacchiarotti and Vieta2020), and medical staff management in psychiatric hospitals such as electronic tracking of staff movement might facilitate contact tracing (Poremski et al., Reference Poremski, Subner, Lam, Kin, Dev, Mok and Fung2020). However, follow-up studies on how effective these interventions were in mitigating COVID-19's mental health impacts on mentally ill patients are needed. These studies should balance the risks and benefits of these alternative interventions on mental health services among patients and providers.

Opportunity to develop evidence-based digital mental health

The potential of digital therapy programs which can offer cost-effective evidence-based therapies has not been fully realized. However, awareness of the disparities in access to the technology of poorer populations and cultural and linguistically diverse communities in low- and middle-income countries may have an impact on their implementation (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Araya, Marsch, Unutzer, Patel and Bartels2017). The effectiveness of digital mental health interventions in such countries has not been rigorously evaluated. Online mental health services’ utilization is still low in China and Australia (Yao, Chen, & Xu, Reference Yao, Chen and Xu2020). However, telehealth remains a valuable way of reducing psychosocial distress without increasing the risk of infection. During infectious disease outbreaks, tele-mental health services can enable remote triaging of care, offer cognitive and/or relaxation skills to deal with stress symptoms, encourage access to online self-help programs, and deliver professional psychological interventions if necessary. Simple communication methods such as e-mail and text messaging can and should be used more extensively in low-income countries. However, many of these interventions require more rigorous assessments to determine their efficacy, effectiveness, treatment retention, and outcomes. Investing in the collection of evidence on the outcomes, workforce requirements, patient engagement, and ethical uses of tele-mental health services will allow them to truly deliver their full potential (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Thomas, Snoswell, Haydon, Mehrotra, Clemensen and Caffery2020). Telehealth and digital services should not completely replace face-to-face treatment for patients in need, particularly those requiring intensive mental health treatment and support including wider deployment of injectable long-acting medications and hands-on interventions such as electroconvulsive and transcranial magnetic stimulation therapies, when in-person contact is once again safe.

Limitations

Several limitations of this systematic review need to be considered. First, few RCTs on the effectiveness of mental healthcare interventions on mitigating mental problems during any of these infectious disease outbreaks were identified, and more high-quality RCT studies are needed. Second, due to the limited number of studies on psychological interventions during infectious disease outbreaks, and the heterogeneity of evaluation methods, we only could provide a systematic review without a formal meta-analysis. Third, relatively few countries have reported mental health services and treatments during infectious disease outbreaks, more high-quality studies are in need to form culture-adapted efficient and nationally unique mental health responses for infectious disease outbreaks.

Conclusion

The pandemic of COVID-19 brings huge challenges for mental health systems worldwide which have to rapidly change, but also can offer an opportunity for improvement of mental health responses, and lead to long-term development of sustainable mental health care systems. Despite differences in political, social, and health systems, mental health services worldwide have implemented acute responses that focus on care for mental health service users, and have facilitated access to mental health assessment and care for new-onset or high-risk patients. More evidence-based interventions should be implemented during epidemics especially for vulnerable populations such as children, older adults, and healthcare workers. The effectiveness of alternative digital interventions in mitigating the mental health consequences on mental services and patients should be assessed in follow-up studies.

Tele-mental health strategies and global cooperation are sound approaches to develop and implement mental health systems to cope with the current COVID-19 pandemic and to improve mental health response capacity for future comparable infectious disease outbreaks. During infectious disease outbreaks, expanded access to cost-effective approaches for delivering effective mental health services should be a priority and retain effective existing services and promote new practices. Effective existing practices should be refined and scaled up, and the usefulness and limitations of remote health delivery should be recognized. Culturally-adapted and cost-effective mental health emergency systems based on evidence-based intervention methods integrated into public health emergency responses at the national and global levels are recommended to reduce the psychological impacts of infectious disease outbreaks, especially for COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate An-Yi Zhang, Yi-Jie Wang, Xiao-Xing Liu, Xi-Mei Zhu, Ze Yuan, Chen-Wei Yuan and Meng-Ni Jing for their help with the data search.

Financial support

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81761128036, 81821092 and 31900805), the Special Research Fund of PKUHSC for Prevention and Control of COVID-19 (no. BMU2020HKYZX008) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2019YFA0706200). GT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London at King's College London NHS Foundation Trust, and by the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. GT also receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). GT is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards.

Conflict of interest

None.