Introduction

Depression is a common debilitating mental health problem affecting around 280 million people worldwide (‘Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx)’, n.d.). Understanding the course of depressive illness and its determinants has clinical and scientific importance. For instance, accurate differentiation of patients at high risk of relapse from patients at low risk may help to improve decisions around clinical treatment (Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen, & Beekman, Reference Hardeveld, Spijker, De Graaf, Nolen and Beekman2010). There are some effective treatments that can prevent future episodes, including maintenance antidepressant treatment (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021) and psychological treatments such as CBT (Teasdale et al., Reference Teasdale, Scott, Moore, Hayhurst, Pope and Paykel2001) and mindfulness (Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Hayes, Barrett, Byng, Dalgleish, Kessler and Byford2015), and monitoring within primary care.

Primary care patients who feel well but still take antidepressants as maintenance treatment are commonly seen in clinical practice. There has been a rise in primary care patients staying on antidepressant medication long-term (Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Kessler, Davies, Martin, Thomas and Gunnell2017; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Yuen, Dunn, Mullee, Maskell and Kendrick2009) with 10% of antidepressant users receiving a ‘chronic’ treatment (5 + years) (McCrea et al., 2016). However, prolonged antidepressant treatment could lead to side effects such as emotional numbness (Goodwin, Price, De Bodinat, & Laredo, Reference Goodwin, Price, De Bodinat and Laredo2017), weight gain, sleep disturbance, and sexual dysfunction (Fava, Gatti, Belaise, Guidi, & Offidani, Reference Fava, Gatti, Belaise, Guidi and Offidani2015; Rosenbaum, Fava, Hoog, Ascroft, & Krebs, Reference Rosenbaum, Fava, Hoog, Ascroft and Krebs1998) (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Gatti, Belaise, Guidi and Offidani2015). There is comprehensive evidence on the clinical effectiveness of antidepressants as maintenance treatment (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Carney, Davies, Furukawa, Kupfer, Frank and Goodwin2003; Glue, Donovan, Kolluri, & Emir, Reference Glue, Donovan, Kolluri and Emir2010; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Macdonald, Atkinson, Buchanan, Downes and Dougall2012; Kaymaz, Van Os, Loonen, & Nolen, Reference Kaymaz, Van Os, Loonen and Nolen2008), though to manage treatment it might also be useful to know the likelihood of a future relapse in this population. The current NICE guidelines (National Institute for Health Care and Excellence, 2022) recognize that some people are at increased risk of relapse and in those cases are recommend continued maintenance treatment for up to 2 years. For NICE, an increased risk was defined as a history of recurrent episodes, incomplete response to treatment, a history of severe depression, unhelpful coping styles amongst other factors. However, NICE acknowledged the low quality of the evidence supporting this recommendation and the lack of research in the primary care population where the vast majority of depression is treated. Our study addresses that gap by investigating factors that could be easily assessed clinically within the primary care setting to better inform treatment decisions for people who feel better and are considering stopping maintenance treatment.

Existing evidence from systematic reviews of antidepressant maintenance, albeit from regulatory trials, suggest that residual depressive symptoms and history of depression are the main factors that influence risk of relapse. However, the evidence suggest that patients with one or more previous episodes have higher risk of relapse than patients with a first episode irrespective of treatment (Geddes et al., Reference Geddes, Carney, Davies, Furukawa, Kupfer, Frank and Goodwin2003; Kaymaz et al., Reference Kaymaz, Van Os, Loonen and Nolen2008). There is also evidence that residual symptoms are associated with relapse in depression, though the type and intensity of the symptoms are yet to be fully determined, as some studies had no minimum score set for symptoms severity (Iovieno, Van Nieuwenhuizen, Clain, Baer, & Nierenberg, Reference Iovieno, Van Nieuwenhuizen, Clain, Baer and Nierenberg2011). The evidence for the episode length and age of onset as risk factors is sparse because the studies that investigated these factors may lack power and the studies (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Wiltse, Walker, Brecht, Chen and Perahia2009; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Stewart, Quitkin, Chen, Alpert, Nierenberg and Petkova2006) have not considered that these factors are potentially confounded. It is also possible that these factors are less researched as they are considered less important than other potential risk factors.

Even without these limitations, the previous evidence comes from studies conducted in specialist mental healthcare services and is unlikely to be generalizable to UK primary care settings where most people with depression seek help (Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Dowrick, McBride, Howe, Clarke, Maisey and Smith2009). For example, patients with fewer than three previous episodes of depression were excluded in one study (Conradi et al., Reference Conradi, de Jonge, Kluiter, Smit, van der Meer, Jennifer and Ormel2007) or studies enrolled patients who had relatively brief periods on antidepressants, 6 months or less. However, many primary care patients take antidepressants for many years, they did not start them after diagnostic criteria and other exclusions (Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Dowrick, McBride, Howe, Clarke, Maisey and Smith2009; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Rossom, Beck, Waitzfelder, Coleman, Stewart and Shortreed2015) were applied. Therefore, the results from the previous literature might be difficult to generalize to patients currently being treated with maintenance antidepressant treatment in UK primary care.

We are only aware of two relevant studies that examined factors associated with relapse in depression in primary care patients receiving long-term antidepressants medication (Conradi, de Jonge, & Ormel, Reference Conradi, de Jonge and Ormel2008; Gopinath, Katon, Russo, & Ludman, Reference Gopinath, Katon, Russo and Ludman2007). Conradi et al. (Reference Conradi, de Jonge and Ormel2008) reported that number of previous episodes were associated with relapse but not duration of the longest episode, nor residual symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, this sample of 110 patients from Netherlands primary care (Conradi et al., Reference Conradi, de Jonge and Ormel2008) was small and likely lacked statistical power. Gopinath et al. (Reference Gopinath, Katon, Russo and Ludman2007) in a larger cohort of 386 primary care patients in US (Gopinath et al., Reference Gopinath, Katon, Russo and Ludman2007) found that residual depressive symptoms, an increasing number of prior episodes, and comorbid anxiety or panic symptoms were associated with relapse. However, the study used a sample limited to patients with either three previous depressive episodes or dysthymia.

We conducted secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial of discontinuing antidepressant treatment in a primary care population on maintenance antidepressants who did not meet criteria for ICD10 depression. On the basis of previous literature, we investigated whether clinical factors of age of onset, duration of last episode number of previous episodes and residual symptoms of depression and anxiety were associated with relapse.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted secondary analyses of the ANTidepressants to prevent reLapse in dEpRession (ANTLER) study. ANTLER was a double blind individually randomized parallel group-controlled trial that was registered with ISRCTN (ISRCTN15969819). The full protocol and results (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Bacon, Clarke, Donkor, Freemantle, Gilbody and Lewis2019, Reference Duffy, Clarke, Lewis, Marston, Freemantle, Gilbody and Lewis2021; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021) are published, in brief: participants were recruited from 150 primary care practices at four study sites: London, Bristol, Southampton and York. Patients were identified via database searches or during consultation and were eligible if they were aged 18 to 74, had experienced at least two episodes of depression; had been taking antidepressants for 9 months or more but were well enough to consider stopping medication. We excluded those who had a comorbid psychiatric disorder, current depression diagnosis according to ICD-10 at baseline, were unable to complete the questionnaires in English, or who had major alcohol or substance abuse. The trial compared maintenance with one of citalopram 20 mg, sertraline 100 mg, fluoxetine 20 mg or mirtazapine 30 mg with discontinuation of medication after a tapering period, with replacement by placebo. The randomization was minimized by the four study sites, the four medications and severity of depressive symptoms at baseline (two categories measured using the Clinical Interview Schedule, Revised (CIS-R [Lewis, Pelosi, Araya, & Dunn, Reference Lewis, Pelosi, Araya and Dunn1992]) a self-administered computerized diagnostic questionnaire.

The ANTLER trial was approved by the National Research Ethics Service committee, East of England – Cambridge South (ref: 16/EE/0032). Clinical trial authorization was granted by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

There are methodological challenges in distinguishing relapse (re-experience of a current episode) and recurrence (a new episode of depression after a period of recovery) due to a requirement for frequent and regular assessments and limitations of the scales used to measure depressive symptoms (Duffy, Marston, Lewis, & Lewis, Reference Duffy, Marston, Lewis and Lewis2023). In our study the term ‘relapse’ refers to any new reappearance of depressive symptoms.

Time to relapse of depression was the primary outcome, assessed by the retrospective CIS-R (rCIS-R) (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021), which asked about the previous 12 weeks, at the 12, 26, 39 and 52 week follow-ups. Five sections (depressive mood, depressive ideas, concentration, sleep, and fatigue) were used to assess symptoms, their duration, their intensity during the worst week and when the symptom/s began. In our analysis, relapse on the rCIS-R was defined according to ICD10 criteria: the participant must have two of depressed mood, loss of interest, reduction in energy plus at least two of the remaining seven symptoms (loss of confidence/self-esteem, recurrent thoughts of suicide or death, change in appetite and weight change, change in psychomotor activity (agitation or retardation), diminished ability to think or concentrate, sleep disturbance).

The results of test-retest reliability study of the rCIS-R and its construct validity in relation to a Global Rating Question about worsening mood, participants stopping their study medication and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores are described in a separate paper. (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Marston, Lewis and Lewis2023). There is strong evidence that rCIS-R is a reliable and valid measure of assessing relapse in depression.

At each time point, participants also completed the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a nine-item self-administered questionnaire for measuring DSM-IV depressive symptoms. Each of the nine symptom items have four response options ranging from ‘0’ (not at all) to ‘3’ (nearly every day). Total scores range from zero to 27. We used clinical judgment to create three categories: mild (a score 3 and under), moderate (a score between 4 and 8 inclusive) and high (a score of 9 and above) to indicate the level of residual symptoms. The categories are for descriptive purposes and in the analysis we used PHQ-9 as a continuous variable. At the same time points participants also completed GAD-7, a seven-item questionnaire, that measures anxiety. Each item has four possible responses ranging from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). The score from each item is added to give a total ranging from 0 to 21. We used clinical judgment to create three categories: mild (a score of 2 and less), moderate (scores between 3 and 6 inclusive) and high (scores between 7 and 21) to show level of residual symptoms of anxiety. The categories are for descriptive purposes and in the analysis we used GAD-7 as a continuous variable. If one or two items were missing from either questionnaire, they were replaced by the mean of the items present. If more than two items were missing, the questionnaire was considered missing for that participant.

At baseline we measured sociodemographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, housing and marital status), alcohol consumption, financial difficulties, undergoing psychological therapies as well as history of depression (age of onset of depression, number of episodes, duration of the current (or index) episode) considered as relevant clinical risk factors of relapse.

Statistical methods

We examined differences in baseline demographic characteristics for those who did and did not relapse using χ2 tests.

To investigate predictors of time to relapse, we defined the whole sample as a cohort and adjusted for randomized group as a covariate. We used Cox proportional hazards modeling to investigate the degree to which each clinical factor (age of onset, number of episodes, duration of the current (or index) episode, residual symptoms of depression measured by PHQ-9 and residual symptoms of anxiety measured by GAD-7 at baseline) was associated with time to relapse, adjusting for potential confounders (baseline demographic characteristics). The outcome was time to relapse and clinical factors were classified as exposures. We included three models: the first is adjusted for group allocation, second included group allocation and mutually adjusted clinical factors and the last model was adjusted for all socio-demographic factors as well as group allocation and clinical factors. We believe such an approach provided clinically useful information as clinicians would want to know which factor/s are associated with relapse as they cannot ‘adjust’ for socio-economic and demographic factors. Our choice of confounders included all available variables (gender, age, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, tenure) as they have been flagged as potential confounders in reviewed literature. We report output as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We plotted time to relapse in depression, using Kaplan–Meier plots.

The literature investigating factors associated with relapse has commonly employed secondary data analysis of data from randomized controlled trials (Cipriani et al., Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Chaimani, Atkinson, Ogawa and Geddes2018; Glue et al., Reference Glue, Donovan, Kolluri and Emir2010; Kaymaz et al., Reference Kaymaz, Van Os, Loonen and Nolen2008). In contrast to other studies, our analyses were adjusted for the randomized allocation. In effect, we have the average association between factor and relapse whether the individuals remained on their antidepressant or were discontinued. We have not investigated whether the clinical factors moderated the effect of discontinuation as this will be a low statistical power interaction test and the average association with relapse across both arms of the trial could be argued as an estimate of clinical interest.

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package STATA 14.

Results

Sample characteristics

We included all participants from the ANTLER trial. Out of 478 participants recruited in the trial, one participant was missing data on the main outcome as well as data on clinical factors and was excluded from the analysis. A further nine participants had missing data on the timing of relapse and were excluded from the survival analysis. As previously described (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021) the maintenance and discontinuation groups were similar in baseline characteristics. Our analysis of differences in baseline characteristics with respect to relapse is shown in Table 1. Apart from education where there were more relapses among more educated participants, there was little difference between the two groups (relapses v. non-relapses) in terms of the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants (n, %) in relation to relapse status

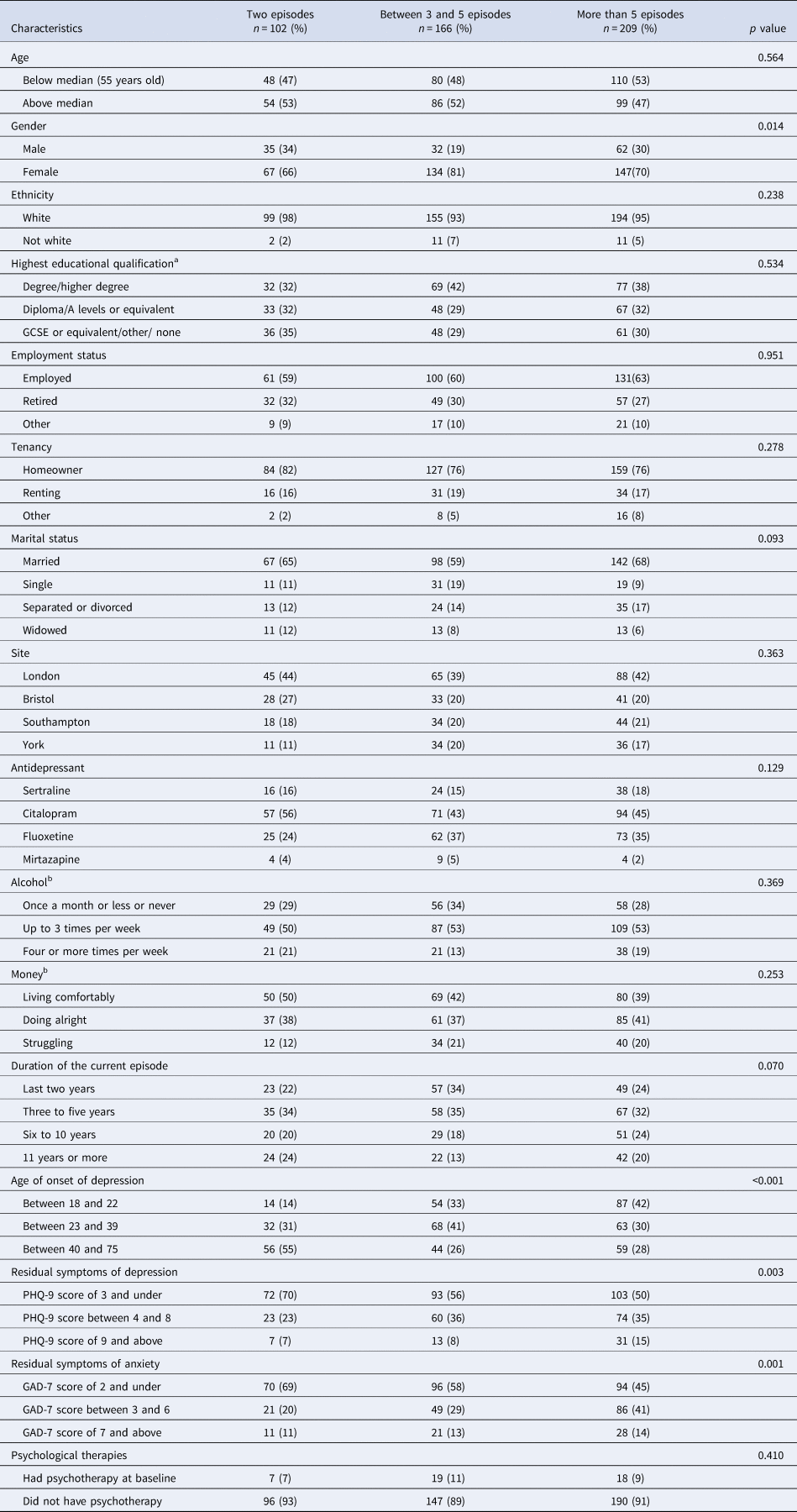

Table 2 shows those with higher number of previous episodes were more likely to be female, to have a younger age of onset of depression and higher residual symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline than those with fewer episodes.

Table 2. Number of episodes in relation to baseline characteristics and possible confounding factors

a n = 468.

b n = 470.

The number of relapses within each group is presented as percentage.

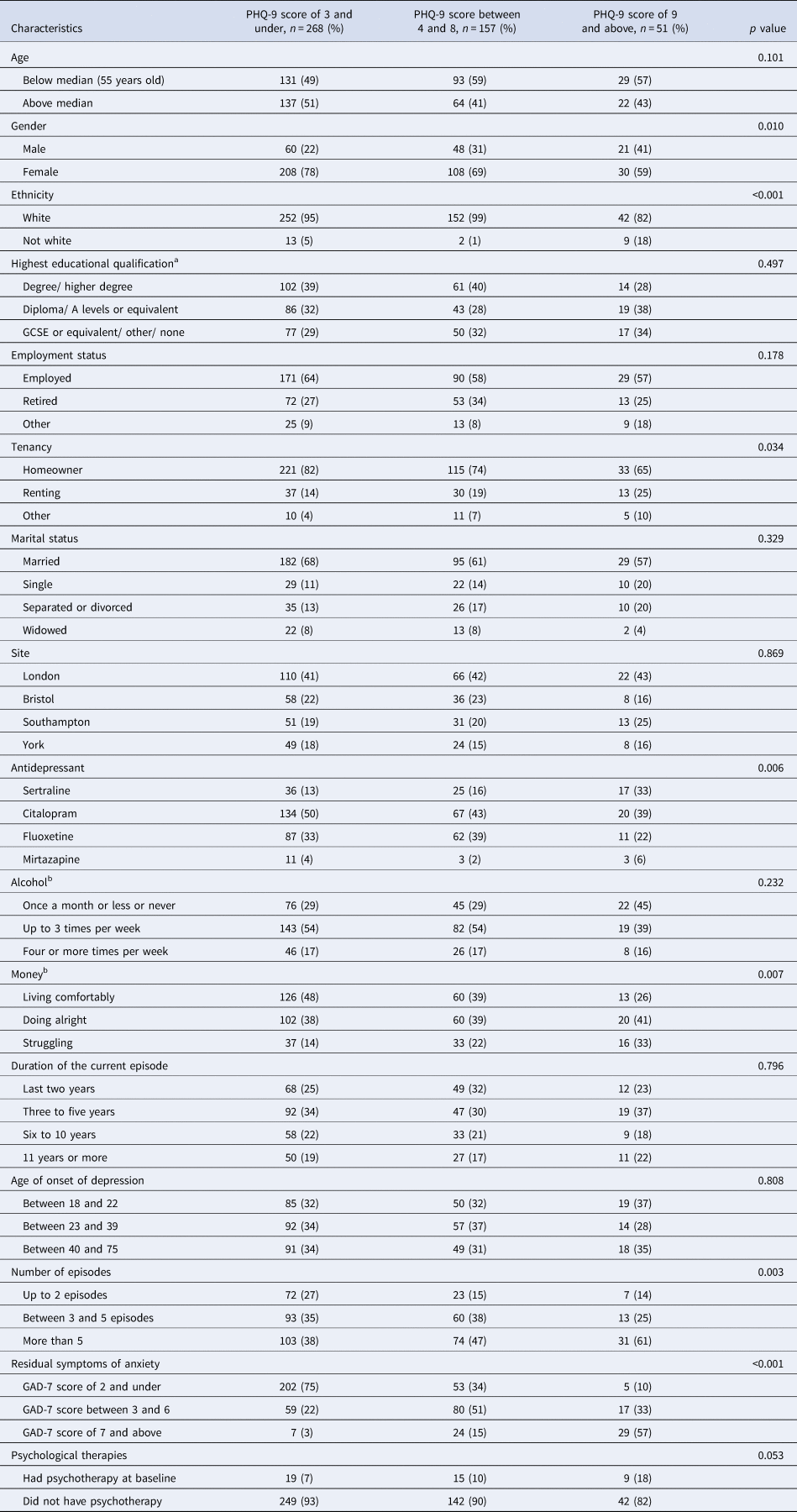

Participants with a higher level of residual symptoms of depression at baseline were likely to be female, experiencing financial struggles; had higher level of residual symptoms of anxiety at baseline and higher number of previous episodes of depression (Table 3). Of note, in our sample a PHQ-9 total score of 19 was the highest score.

Table 3. Residual symptoms of depression in relation to baseline characteristics and possible confounding factors

The number of relapses within each group is presented as percentage.

a n = 468.

b n = 470.

Similar tables for other clinical factors (i.e. age of onset, duration of current episode and residual symptoms of anxiety) can be found in online Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

The Kaplan–Meier plots (online Supplementary Figs S1–S3 and Figs 1, 2) show the proportion of participants that relapsed during the 52-week trial in relation to categories within each clinical factor. We are presenting Figs 1 and 2 for number of episodes and residual depression as we had evidence for an association with relapse. Other results are in online Supplementary Figs S1–S3 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the first relapse of depression by 52 weeks among three categories: those with two and less previous episodes or depression, those with between three and five episodes and those with over five episodes.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the first relapse of depression by 52 weeks among three categories of the residual symptoms of depression measured by PHQ-9 at baseline: those with a PHQ-9 score of 3 and under, those with a score of between 4 and 8 and those with a score of 9 and above.

Compared to those with age of onset between 40 to 75 years, early age of onset was associated with increased relapse: those with age of onset between 23- and 39-years old group HR was 1.62 (95% CI 1.13–2.33) and in the age of onset between 18 to 22 group HR 1.37 (95% CI 0.90–1.97) in the model adjusted for group allocation (Table 4). After adjusting for baseline characteristics and other clinical factors the HRs in the two younger groups became similar: age between 23- and 39-years old HR 1.33 (95% CI 0.87–2.02) and age between 18- and 22- years old HR 1.28 (95% CI 0.86–1.92), compared to the reference group. Cox regression analysis of the age of onset as a continuous variable produced strong evidence of association with hazard of relapse: HR 0.86 (95% CI 0.78–0.95) in the model adjusted for group allocation; the HR attenuated in the fully adjusted model HR 0.91 (95% CI 0.81–1.02).

Table 4. Hazard ratios (95% CI) for relapse according to the age of onset, duration of current episode, number of episodes, residual symptoms of depression and residual symptoms of anxiety before and after adjustment

a Adjusted for treatment group allocation.

b Mutuality adjusted clinical factors.

c Adjusted for gender, age, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, tenure, group allocation, psychological therapy and mutuality adjusted clinical factor.

There was weak evidence that longer duration of the current episode (over 10 years) compared with duration between 2 and 10 years, was a risk factor of relapse: HR 1.17 (95% CI 0.88–1.55) in the model adjusted for group allocation and HR 1.24 (95% CI 0.91–1.68) in the fully adjusted model.

The hazard of relapse was highest in participants who had more than five episodes of depression HR 1.84 (95% CI 1.23–2.75) in the model adjusted for group allocation, with 49% patients relapsing in the more than five episodes group compared with 42% in between 3 and 5 episodes group and 32% in up to two episodes group. The HR attenuated slightly after adjusting for baseline characteristics and other clinical factors HR 1.57 (95% CI 1.01–2.43) (Table 4).

There was also evidence that residual symptoms of depression at baseline were associated with increased relapse; with 51% patients relapsing in the PHQ-9 score of 9 and above group compared with 44% relapsed in the PHQ-9 score of between 4 and 8, and 41% relapsed in the score of 3 or below group. Analysis of the PHQ-9 score as a continuous variable found an increase in relapse for each one-unit change in PHQ-9 score: HR 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.09) in the model adjusted for group allocation and HR 1.06 (95% CI 1.01–1.12) in the model adjusted for group allocation, baseline characteristics and other clinical factors.

There was no evidence of an association between residual symptoms of anxiety at baseline and relapse.

Discussion

The results of our secondary analysis of the ANTLER trial provide strong evidence that number of previous episodes and residual symptoms of depression at baseline increased the risk of relapse in a sample of primary care patients, after adjustment for baseline characteristics and other clinical factors. There was some evidence of the age of onset being associated with relapse, though we did not find evidence that duration of last episode and residual symptoms of anxiety were associated with relapse after adjustment for baseline characteristics and other clinical factors.

An important consideration is whether our results are clinically important. One way of judging this is by comparing the 49% relapse in those with five or more episodes with 32% relapse in those with two or fewer episodes. The difference between 5 or more episodes v. 2 or fewer is relatively large and of the same magnitude as the size of difference, that we reported in earlier paper, between maintenance and discontinuation in the ANTLER trial. Such substantial difference within 12 months would be clinically important information to consider when managing a patient with depression. Likewise, for those scoring 9 or more on the PHQ-9, the proportion relapsing was 51% compared to 41% for those scoring 3 or less. We think these unadjusted findings are the most relevant to guide clinical practice as statistical adjustment of findings is not possible in the clinic and furthermore in our analysis adjustments only slightly attenuated the results.

Strengths and limitations

We examined clinical factors that can be easily assessed and monitored in primary care. The strengths of our study are the sample size, the sample recruited from a primary care setting, the excellent follow up rate and the use of reliable outcome measure (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Marston, Lewis and Lewis2023).

Our sample represents only a small proportion (6%) of patients approached (23 553) either by an invitation letter or at consultation, who agreed to take part and proceeded to screening and eligibility checks (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Clarke, Lewis, Marston, Freemantle, Gilbody and Lewis2021; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021). Therefore, representativeness of our sample might be limited because the population recruited into RCT might differ in some ways from the population that would be potentially eligible. However, in general it is thought that the inclusion criteria and any selection bias into a cohort study are less likely to limit the validity of comparisons within a cohort.

Our study was one of few to examine clinical factors of relapse in the primary care population. Although the sample size was substantial, our analyses were limited by relatively small numbers in some sub-groups and therefore had a limited power to detect small differences. As a result, we decided not to examine interactions though some are reported in our main trial paper (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Marston, Duffy, Freemantle, Gilbody, Hunter and Lewis2021).

Another possible limitation was recall bias. At baseline, we asked people who have been taking antidepressants for years to recall both the history and treatment of their depressive illness. It is possible that some information was inaccurate and reduced the precision of our results, though it is unlikely to have biased the results as these data were collected before the outcome occurred. This method of asking about previous history is similar to that used in clinical practice.

The trial had a relatively short tapering period of two months, and some relapses could have been affected by withdrawal symptoms. To avoid this possibility, we used ICD10 criteria to assess relapse in depression, so it is unlikely withdrawal symptoms were mistaken for relapse.

Implications for practice

The results of our study suggest that the number of previous episodes and presence of residual symptoms are two clinical factors that are associated with relapse and can be used as prognostic factors. Asking about previous episodes and assessing residual symptoms can become a routine part of the consultation where stopping treatment is being discussed. For example, if the benefits of antidepressant maintenance followed a relative risk pattern, one would expect a greater absolute risk reduction for individuals who have a higher risk of relapse. Certainly, knowing someone already has a poor prognosis would likely affect the decision to stop or continue with any treatment.

Implications for further research

Large observational studies are needed in primary care settings investigating a range of factors that might be associated with future relapse. There is potential for identifying other clinical and psychological feature such as history of severe depression and coping styles. Considering the clinical importance and frequency of depression knowing the likely outcomes in primary care would be important information in guiding treatment decisions. Descriptive information on likely outcomes would be useful information for both patients and doctors and would influence management of the illness.

We focused on identifying the clinical factors that are important for outcome irrespective of treatment. Further research is needed to examine a range of possible factors that might affect the response to treatment.

What is already known on this topic

• Antidepressants are effective at preventing relapse of depression

• Residual depressive symptoms and history of depression are the main factors that influence risk of relapse

• Existing evidence predominately comes from studies set in specialist mental healthcare services and is unlikely to be generalizable to UK primary care settings where most people with depression seek help

What study adds

• In primary care settings the number of previous episodes is one of most relevant clinical factors affecting relapse in depression

• In primary care presence of residual symptoms is one of most relevant clinical factors affecting relapse in depression

• Making assessment of the two clinical factors routine practice may help to inform joint decision making when patients when considering future treatment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723002659

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients that took part in the ANTLER trial. We thank the staff in participating general practitioner surgeries for their help with recruitment. We acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding statement

The ANTLER trial was independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme 13/115/48. The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of this paper. The corresponding author had full access to all data used in the study, and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. We acknowledge the support of the UCLH BRC.

Competing interest

None.