Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is the psychological approach with the most evidence for efficacy across a range of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety and some eating disorders (Department of Health, 2001; National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004a , b ). However, the role of the psychiatrist in the provision of CBT is unclear and requires further attention (Reference Le Fevre and GoldbeckLe Fevre & Goldbeck, 2001; Reference Swift, Durkin and BeusterSwift et al, 2004).

Training in CBT that is available to the psychiatrist ranges from local arrangements for senior house officers as part of basic specialist training, through to more formal postgraduate certificate or diploma courses typically costing £2500-£3500. Attendance can count towards gaining accreditation with the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) - the lead body for CBT in the UK (http://www.BABCP.com).

The training guidelines of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2002) have fully endorsed training in CBT for all psychiatrists. A number of surveys have confirmed that it can prove difficult for practitioners to build upon the CBT skills they learn in postgraduate courses (Reference Ashworth, Williams and BlackburnAshworth et al, 1999; Reference Gournay, Denford and ParrGournay et al, 2000; Reference Hull and SwanHull & Swan, 2003). Le Fevre and Goldbeck (Reference Le Fevre and Goldbeck2001) surveyed all Scottish consultant psychiatrists and found that of the 268 respondents, 24 (9%) had received formal training from an accredited CBT course, and a total of 39 (15%) carried out formal CBT in their routine National Health Service practice. A recent UK-wide survey of BABCP-accredited psychiatrists (Reference Swift, Durkin and BeusterSwift et al, 2004) found that only 4 of 17 (24%) non-psychotherapy post holders were satisfied with the extent to which they used their CBT skills, compared with 12 of the 15 (80%) psychotherapy post-holders. In view of the lack of detailed information on the use of CBT skills by psychiatrists trained to certificate/diploma level in CBT, we conducted a survey of all such psychiatrists identified in Scotland.

Method

Psychiatrists working in Scotland who had previously attended a specialist postgraduate certificate or diploma course in CBT were surveyed. The course administrators of both certificate/diploma courses in Scotland (Dundee and South of Scotland) provided a complete list of all psychiatrists who had attended the CBT courses since their inception. Five additional psychiatrists currently working in Scotland were also known to the authors as having attended CBT certificate/diploma courses in England and were added to the study population. All four of the current authors similarly completed questionnaires (included among the 51 respondents).

We used an abbreviated version of a questionnaire used in a previous CBT course audit (Reference Ashworth, Williams and BlackburnAshworth et al, 1999) and altered for a survey of UK-wide BABCP-accredited psychiatrists (Reference Swift, Durkin and BeusterSwift et al, 2004). The questionnaire asked the psychiatrist's gender, professional grade and the year of attendance at the CBT certificate or diploma course. A yes/no question asked whether cognitive therapy was the ‘ main focus’ of their current job description. We asked whether the psychiatrists ‘continued to use cognitive therapy as a technique with patients’ and for the reasons why they were not using CBT if this was the case. A 7-point Likert-type scale allowed the practitioners to subjectively rate their current skills in CBT relative to their skills at the end of the CBT course. A response of 1 equated to ‘a lot worse’, through to 7 which equated to ‘a lot better’. The remainder of the questionnaire assessed continuing professional development, supervision (both received and given) and BABCP membership status.

The participants were not asked to disclose their identity on the questionnaires. The questionnaire was given to 9 psychiatrists attending the South of Scotland CBT workshop in February 2003 and sent on one occasion only to a further 49 psychiatrists in June 2003. A self-addressed envelope for postage back to the authors was included but no further incentives were given. The results were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 11.5 for Windows.

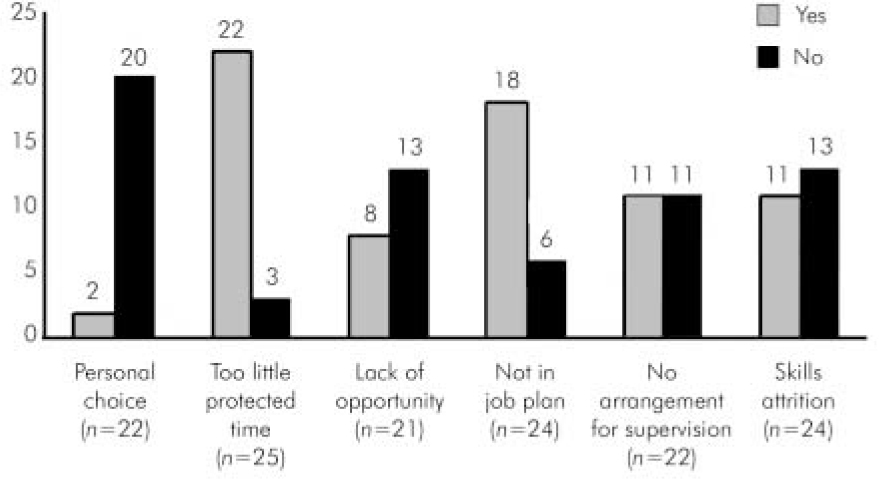

Fig. 1. Reasons given for not using cognitive-behavioural therapy (multiple responses were accepted).

Results

Of the 58 psychiatrists approached, 51 responded, giving a response rate of 88%. Of the respondents, 24 (47%) were men and 27 (53%) were women. Most were consultants (39, 76%); 9 (18%) were specialist registrars and 3 (6%) were staff grades.

Year of CBT certificate/diploma course

The consultants had completed their postgraduate courses a mean of 6.21 years (s.d.=3.64) prior to the survey, whereas the specialist registrars and staff grades together as a group completed their training a mean of 3.67 years (s.d.=1.83) previously.

Use of CBT since the course

When the psychiatrists were asked whether they ‘continued to use cognitive therapy as a technique with patients’, 31 (61%) said they did with ‘some of their case-load’, 12 (24%) said that cognitive therapy was their ‘predominant therapeutic approach’, and 7 (14%, all consultants) said ‘No, or only very occasionally’. One (2%) did not respond. When asked if CBT was the ‘main focus’ of their current job, 40 (78%) said that it was not, 9 (18%) responded that it was and 2 (4%) did not respond to this item. A greater proportion of the non-consultant staff said that CBT was the main focus of their job (5 of 12, 42%) relative to the consultant group (4 of 37 or 11%, χ2=5.75, d.f.=1, P=0.016).

Reason for not using CBT

Personal choice was clearly not the reason why most psychiatrists were not practising CBT: 20 of the 22 (91%) respondents to this question specifically answered ‘No’ to this with only two (9%) answering ‘ Yes’ (Fig. 1). Other reasons given were ‘too little protected time’, with 22 of 25 (88%) responding ‘yes’ to this item. Of 24 respondents, 18 (75%) stated that not having CBT in their ‘job plan’ was a reason.

Supervision provided to others

Just under half of the responders (23, 45%) offered CBT supervision to trainees, 26 (51%) did not and 2 (4%) did not respond; 16 of the 51 (31%) said that they offered supervision to other team members, 27 (53%) did not and 8 (15.7%) failed to respond. Overall, 24 (47%) supervised either trainees or other team members.

Skills attrition

Using the Likert-type scale for the subjective assessment of skills, the consultant group (n=38, 1 missing response) rated their CBT skills as having on average stayed the same since the CBT certificate or diploma course (mean=4.08, s.d.=1.58). The non-consultant group (n=12) believed that their CBT skills had improved (mean=5.25, s.d.=1.22). This mean difference in subjective skill attrition between the two professional groups was statistically significant (t=–2.35, d.f.=48, P=0.023). There was no significant correlation between the years that had elapsed since course attendance and the degree of skill attrition among the 50 respondents to this item (Pearson correlation=–0.123, P=0.4).

Supervision received

About half of the psychiatrists (25, 49%) received CBT supervision for their own practice, 24 (47%) said they did not and 2 (4%) did not respond to this item. A significantly greater proportion of the non-consultants (10 of 12, 83%) were receiving supervision than the consultants (15 of 37 respondents, 41%, χ2=6.64, d.f.=1, P=0.01). Eighteen psychiatrists (16 of these consultants) continued to use CBT with at least some patients, but were not receiving CBT supervision. Those who received supervision for their own practice were more likely to provide supervision for trainees (χ2=5.07, d.f.=1, P=0.024). Nevertheless, 6 psychiatrists (all consultants) supervised trainees but were not receiving supervision themselves.

Continuing professional development

Eighteen psychiatrists (35%) had not attended any formal training in CBT in the past year, 20 (39%) had attended 1 or 2 training days, and a further 11 (22%) had attended 3 or more. The majority (44, 86%) were interested in further cognitive therapy training. Of the responding psychiatrists, 30 (59%) were current members of the BABCP; 21 (41%) responded that they were not.

Discussion

A notable strength of this survey is the high response rate (88%). We can be reasonably confident that the survey results paint an accurate picture of the cognitive-behavioural practices of the majority of psychiatrists in Scotland who have been trained in this model to diploma/certificate level.

In common with the current survey, Ashworth et al (Reference Ashworth, Williams and Blackburn1999) noted that doctors saw only a small number of patients after completing the certificate/diploma course. The current study showed that this is likely to be owing to a lack of relevant job planning, supervision arrangements and protected time for CBT. Indeed, CBT has frequently been seen as the domain of psychologists or nurses in current UK mental health services. However, psychiatric consultants tend to have a wide experience of teaching, multiprofessional working, and managing and supporting teams. The psychiatrist therefore has the potential to integrate multiple factors within a cognitive-behavioural formulation and management plan for the purposes of teaching, and the management of patients.

It is worrying that 22 of the 37 responding consultants (59%) were not receiving supervision for their CBT practice, particularly as the majority of these continued to provide some CBT and (in 6 cases) provide supervision to juniors. These figures compare very unfavourably with a UK-wide study of cognitive-behavioural psychotherapists from all professional backgrounds, of whom 90% were being supervised (Reference Townend, Iannetta and FreestonTownend et al, 2002). Supervision of CBT practice is an essential element of continuing professional development even in those therapists who do not need or wish to have formal accreditation with the BABCP (Reference Townend, Iannetta and FreestonTownend et al, 2002). Likewise, over half of the psychiatrists in the current survey were not supervising others (trainees or other team members) in the CBT model. In view of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ emphasis on training juniors in psychological approaches this was surprising.

There appears to be a real opportunity to assist in the provision of continuing professional development for psychiatrists with an interest in CBT. This could assist in the maintenance of morale in a group that frequently perceive their professional role and identity as having been excessively narrowed. The finding that having ‘too little protected time’ and ‘ not having CBT in a personal job plan’ are the two most common blocks to engaging in CBT has important implications for consultant job planning.

In conclusion, our findings point to a population of CBT-trained Scottish psychiatrists who rarely use CBT, who are dissatisfied with this situation and who in the main neither provide supervision to others nor receive supervision for their own CBT practice. This situation represents a wasted resource. Planners should think carefully about how to harness and hold on to psychiatrists with these skills if future diversity in psychological skills training is to be assured.

Declaration of interest

M. Connolly is a co-director and supervisor on the South of Scotland certificate and diploma CBT course. All authors have themselves attended CBT certificate or diploma courses.

Acknowledgements

We thank all medical staff who returned the questionnaires, the BABCP who provided the figures about therapist accreditation, and the administrators of the Dundee and South of Scotland CBT diploma course for their assistance.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.