Donepezil was the first drug to receive a licence in the UK (in the spring of 1997) for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. At the time there was only one published clinical trial using the drug (Reference Rogers and FriedhoffRogers & Friedhoff, 1996) and this had shown only modest improvement in cognitive performance in patients with Alzheimer's disease. It was estimated that the annual cost of drug treatment (excluding any other costs, e.g. investigations) would be about £1000 per patient. As a result there was widespread uncertainty among both clinicians and health service managers in many parts of the country concerning the cost-effectiveness of providing this treatment (Alzheimer's Disease Society, 1997). Thus, in some parts of the country the policy was simply not to prescribe, while in other areas local guidelines were developed for prescribing donepezil (Reference HarveyHarvey, 1999).

In Leicestershire it was decided that donepezil should be available but the treatment should be targeted at patients for whom there is evidence of benefit. To achieve this a local protocol for prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors was developed and employed from the outset (see Appendix). One of the requirements of the protocol was that the pattern of use of donepezil and compliance with the protocol should be monitored. As a consequence a prospective clinical audit was undertaken. The audit also provided an opportunity to examine systematically the outcome of therapy in a routine clinical setting, an area in which there are few published data at present.

Method

Setting

The audit was carried out at the Bennion Centre, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester. This is the base hospital for oldage psychiatric services covering the western half of the city of Leicester and Leicestershire, with a catchment population of approximately 70 000 persons aged 65 and over.

Subjects and procedures

All patients initially considered for donepezil treatment between 1 August 1997 and 31 July 1998 were included in the audit. They received a standardised assessment of dementia severity, cognitive and functional status and other parameters. This included the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Reference Hughes, Berg and DanzigerHughes et al, 1982), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHughFolstein et al, 1975), Barthel ADL (activities of daily living) Index (BAI; Reference Mahoney and BarthelMahoney & Barthel, 1964) and a check-list covering various non-cognitive features of dementia. Case notes were reviewed to determine the basis for the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease. Following the initial assessment those who then went on to receive the treatment were reassessed 8-12 weeks later with the same measures. In addition, pre- and post-treatment questionnaires were sent to each patient's main carer to assess their knowledge and expectations of treatment.

Results

Patient selection and characteristics

Between 1 August 1997 and 31 July 1998, 62 patients were considered for donepezil treatment. Of these, 35 eventually received treatment. The characteristics of the treated and untreated groups are shown in Table 1. The groups differed only in mean age (t=3.52, P=0.001). Reasons for eventual non-treatment included failure to meet diagnostic or other eligibility criteria (44%), refusal of the general practitioner to continue treatment (30%) and other factors including problems of follow-up (26%); for example, patient moving out of the area. Of the 35 treated patients, complete 12-week follow-up data were available for 25 of them. Four patients had discontinued before 12 weeks and for the remainder only incomplete data were available.

Table 1. Characteristics of treated and non-treated patients

| Treated (n=35) | Non-treated (n=27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 71.8*** | 79.2 |

| Male:female | 13:22 | 7:20 |

| Mean MMSE score | 20.4 | 18.9 |

| Mean BAI score | 18.9 | 17.7 |

| Severe dementia - CDR>2 (%) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (11.1) |

| Living with spouse or family (%) | 24 (68.6) | 12 (44.4) |

With respect to non-cognitive symptoms there were no significant differences between the treated and non-treated groups with the exception of weight loss and aggression, which were present in a significantly greater number of non-treated (P<0.05; Fisher's exact test).

Therapeutic outcome

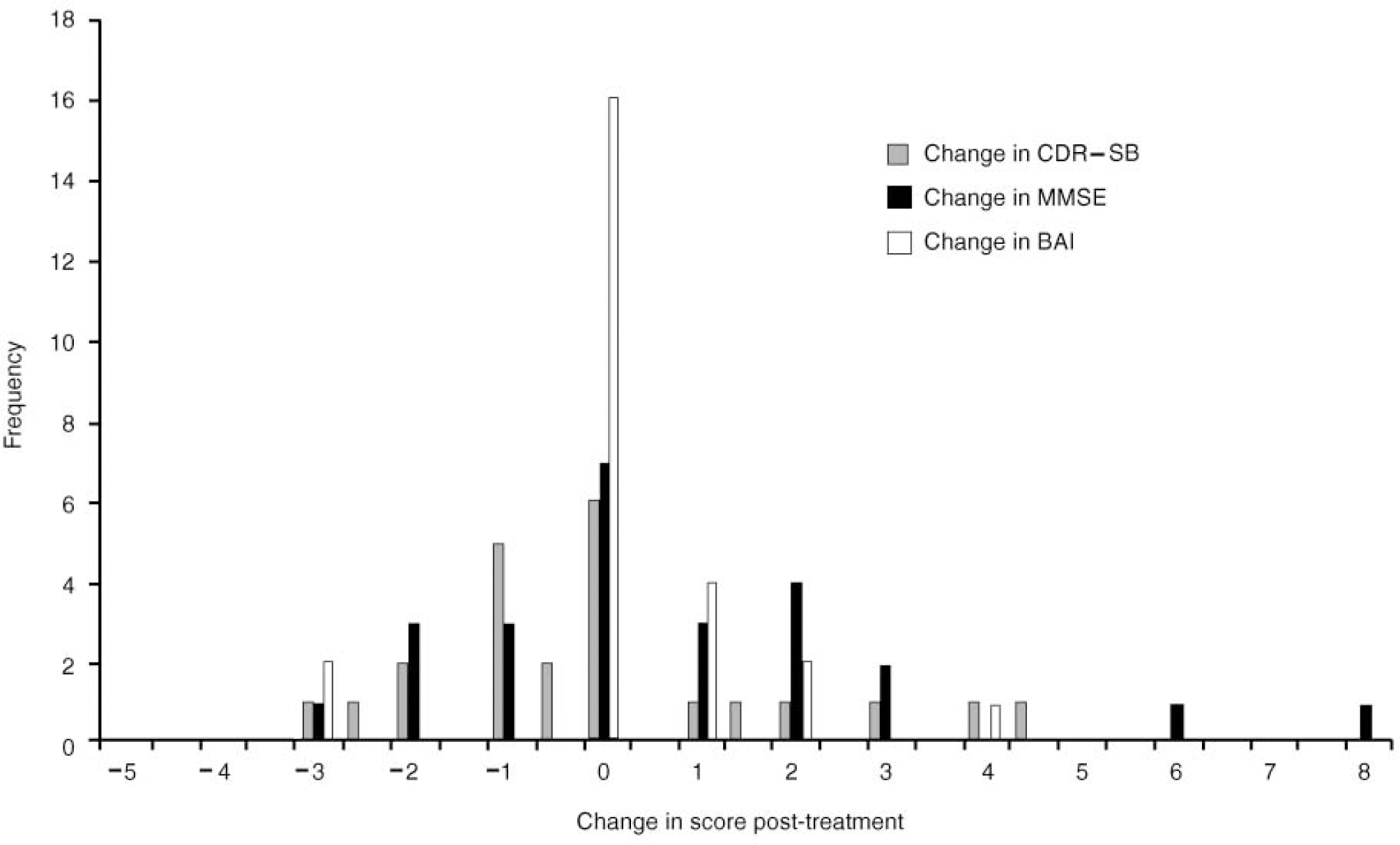

Mean changes in MMSE, BAI and CDR—SB (sum of boxes) scores were not statistically significant (see Table 2) although a few individuals showed larger changes on one or both measures (see Fig. 1). These findings were broadly in line with clinicians' general impressions of a small minority of patients demonstrating a marked overall clinical change.

Table 2. Mean Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Barthal ADL (activities of daily living) Index (BAI) and Clinical Dementia Rating scale - sum of boxes (CDR-SB) scores: baseline and post-treatment (n=25)

| Mean baseline | Mean post-treatment | Mean difference (95% Cl) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 21.0 | 21.9 | 0.9 (-0.1 to 1.9) | 0.09 |

| BAI | 18.6 | 18.9 | 0.3 (-0.3 to 0.8) | 0.11 |

| CDR-SB | 6.2 | 6.0 | -0.2 (-1.1 to 0.7) | 0.39 |

Fig. 1 Change in Clinical Dementia Rating scale — sum of boxes (CDR—SB), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Barthel ADL (activities of daily living) Index (BAI): post-treatment against baseline

Sixty-nine per cent of carers reported ‘some’ or ‘marked’ improvement (number of responders=16). The most frequently cited areas of improvement were in mood (n=7; 44%) and sociability (n=8; 50%). In eight cases (50%) carers stated that the degree of improvement was less than they had anticipated.

Discontinuation of treatment

At the 12-week follow-up four of the 35 patients discontinued treatment; two owing to side-effects (gastrointestinal), one owing to rapid deterioration and one owing to death (unrelated to treatment). In addition to this, five carers reported possible side-effects that were mild and transient. These included minor gastrointestinal upset (two), insomnia (one), mood swings (one) and muscular aches (one). As at 31 July 1999, a further 22 patients had discontinued treatment; nine owing to lack of benefit, 12 owing to deterioration and one owing to death (again, this was unrelated to treatment). There were no further cases of discontinuation because of side-effects and nine of the 35 patients who had commenced treatment were still continuing treatment as at 31 July 1999. Of the 26 patients who had discontinued treatment, 50% had discontinued by 30 weeks and approximately two-thirds (65%) by 12 months.

Conclusions

The characteristics of the patients selected for treatment with donepezil were broadly in line with the eligibility criteria contained in the protocol. Acceptance of the protocol by the clinicians did not present any significant problems despite the additional work involved in administering the rating scales and questionnaires. During the period described, it appears that resource-related and organisational factors were as important as clinical factors in determining who received treatment. The total number of patients was far less than had been originally anticipated. Although the annual cost of prescribing donepezil has been estimated at £1000 per patient, a significant proportion of the patients did not complete 1 full year's treatment. Thus, the average drug cost per patient treated was significantly less than the estimated cost.

Generally, donepezil appears to be well tolerated, with only two of the 35 patients in this series discontinuing treatment because of adverse effects. The objective outcome measures employed in this evaluation did not demonstrate a large treatment effect. This would be consistent with either a genuine lack of clinical benefit; with a relative insensitivity of these measures in the target domains together with the possibility of type two error (owing to small numbers); or with a failure to rate those domains that may, in fact, manifest the greatest response to treatment. The latter possibility is reinforced by the subjective clinician and carer impressions of improvement in mood and social functioning. Other authors have also reported noticeable improvements in the non-cognitive features of the condition and the relief and enhancement in quality of life experienced by the patients' carers (Reference Burns, Russell and PageBurns et al, 1999; Reference Watts-TOBIN and HornWatts-Tobin & Horn, 1999). It will be important in future to incorporate into anti-dementia drug trials and evaluations valid measures of personal functioning that assess those areas in which carers report worthwhile improvement.

Finally, donepezil was the first drug (apart from clozapine) prescribed by psychiatrists in Leicestershire to be subjected to a clearly defined protocol for its use. Overall, we did not encounter any significant problems in incorporating the protocol into routine clinical practice. The systematic collection of data on clinical experience with newly introduced drugs usefully complements the evidence available from clinical trials: our experience indicates the feasibility of this approach and its acceptability to prescribers.

Appendix

The Leicestershire Mental Health Service NHS Trust Protocol for the prescribing of cholinesterase inhibitor drugs: 1997 VersionFootnote 1

-

(a) Patients should have a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease. Although this should be a clinical judgement, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria are suggested as guidelines for making the diagnosis.

-

(b) Disease should not have progressed to the severe stage. The Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly severity classification is suggested as a model for assessing the disease stage.

-

(c) There should be assurance of supervision when administering medication in the domestic setting.

-

(d) Treatment is to be initiated by the specialist but the responsibility of ongoing prescribing to be that of the patient's general practitioner.

-

(e) Treatment should be discontinued if disease progresses to the severe stage or if there is no benefit from the treatment after an adequate trial.

-

(f) The treatment response should be regularly monitored — initially at 2-4 weeks, then at 12 weeks and then at 12-weekly intervals.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Ltd.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.