The Mental Health Act 1983 has finally been amended, after several reviews and years of discussion. It was initially intended to be a liberalising act, increasing rights of appeal for detained patients and discouraging the overuse of emergency orders. It was predicted that under this Act the number of tribunal hearings would increase more than fourfold owing to the introduction of new rights to appeal for patients detained under Section 2 or Section 3 (Reference SzmucklerSzmuckler, 1983). The Department of Health data showed that numbers of compulsory admissions almost doubled in the 10 years up to 1996 and the proportion of psychiatric admissions that involved admission under the Mental Health Act increased from 7% to 12% (Department of Health, 1998). More recent data show a slight decline in numbers of detentions under the Mental Health Act after 1998, followed by a further increase to an all-time high in the year 2005-6 (Information Centre, 2007). A study of the use of the Mental Health Act over the same period found that the rate of appeals to and hearings by mental health review tribunals increased faster than the episodes of detention that warranted a tribunal application (Reference LangleyLangley, 1999). Thus, not only has the proportion of those who are detained under the Act risen, but so has the proportion of detained persons who appeal to and are heard by the tribunals. Data from 1987 suggest that the large increase in the number of tribunals after the introduction of the Mental Health Act 1983 did not result in any change in the proportions of detained patients who were discharged by these tribunals (Reference Webster, Dean and KesselWebster et al, 1987). However, there is no more recent information available.

Several studies have found greater than expected compulsory admissions among African-Caribbean patients (Reference Owens, Harrison and BoofOwens et al, 1991). Others have shown that higher proportions of patients of African-Caribbean and Asian origin who were readmitted were detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 when compared with patients of European ethnicity (Reference Thomas, Stone, Osborn, Thomas and FisherThomas et al, 1993).

This study examined trends in the use of the Mental Health Act and rates of appeals to mental health review tribunals and hospital managers’ panels in a hospital covering two outer London boroughs between 1997 and 2007. We examined trends in the outcome of review hearings and associations between the outcome of hearings and demographic characteristics, including ethnicity.

Method

Data were collected from the local Mental Health Act office for the period 1996-2007 to study the trends in number of detentions under the Act, number of appeals, percentage of detentions going to appeal, the result of the appeals and the proportion of appeals that resulted in discharge from the restrictions of the Mental Health Act. Data were restricted to people detained under Sections 2, 3 or 37/41 of the Act, since it is only these sections for which there are rights of appeal. Results of appeals were recorded as ‘compulsory detention upheld’, ‘patient discharged’, ‘no decision, further hearing requested’ and ‘hearing cancelled or adjourned’. The last category was excluded from the analysis, since we wanted to study the pattern of hearings that actually occurred.

The Mental Health Act office routinely collects some demographic details on patients who are detained under a section of the Act. We obtained these data for patients who were compulsorily detained during 2005 and 2006. Data on age, gender, marital status and ethnicity were also collected. These data were used to explore whether there was any factor that was associated with the results of an appeal hearing. For the purposes of this analysis, the results of the hearings were categorised dichotomously into discharged v. not discharged. We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 15 for Windows) for the analysis, and chi-squared and t-tests were performed to examine any associations between hearing result and the demographic characteristics of the individual whom the hearing concerned. For this analysis the unit of analysis was the hearing rather than the individual patient, because some patients had more than one hearing.

Data on ethnicity were first recorded in five categories and then recoded into two categories, White and Black and minority ethnic, for the purposes of analysis. This ensured that there were adequate numbers for a chisquared test to be conducted. Most of the people in the Black and minority ethnic category were of Black African or African-Caribbean ethnicity. Similarly, marital status was coded into two categories - single v. married or in a long-term relationship - and a chi-squared analysis was performed. To examine trends, data were entered into Microsoft Excel, which was used to obtain graphs.

Results

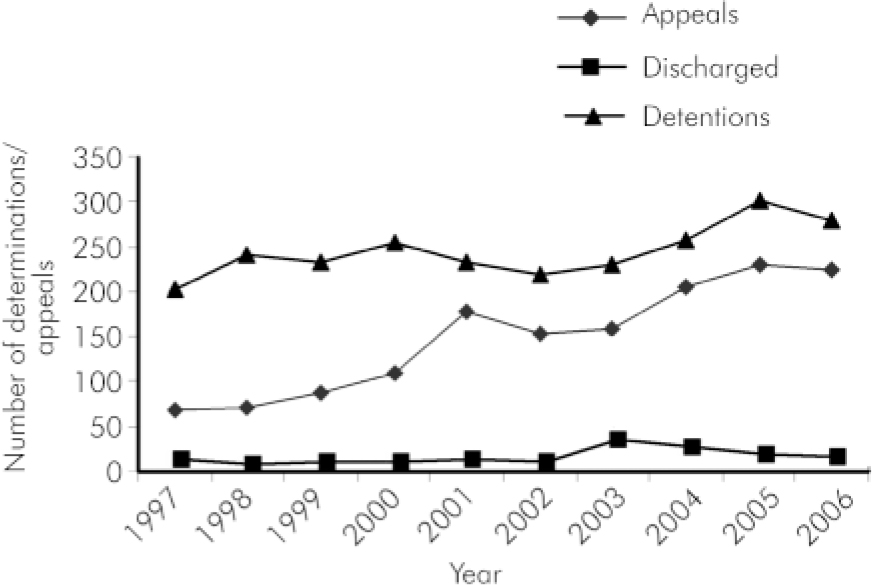

Compulsory detentions under Mental Health Act Sections 2, 3 and 37/41 rose from 203 in 1996 to 279 in 2006 (Fig. 1). The percentage of detentions that went to appeal escalated from 34% to 81% during the same period. However, there was no observed trend in the result of the appeals and the proportions of applicants who were discharged from compulsory detention by the hearing remained unchanged. Two-thirds (66%) of appeals resulted in the power of detention being upheld. Twelve per cent of hearings resulted in the applicant being discharged from detention under the Mental Health Act, and 21% of appeals were adjourned. Table 1 indicates that the results of the appeals were not associated with age, gender, marital status, ethnicity or the Mental Health Act section involved.

Table 1. Exploration of predictors of appeal results

| Test variable | Test statistic | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | t=0.72, d.f.=156 | 0.47 |

| Gender | χ2=1.63, d.f.=1 | 0.20 |

| Marital status | χ2=0.09 | 0.77 |

| Ethnicity | χ2=0.12 | 0.74 |

| Section 2 v. Sections 3 or 37/41 | χ2=0.21 | 0.65 |

Fig. 1. Detentions and appeals 1997-2006.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that there has been a steady increase in the number of detentions and appeals over the past decade, in line with previous findings (Reference Wessely, Wall, Hotopf and ChurchillWessely et al, 1999). This has been accompanied by an increase in the proportion of detentions that are challenged at appeal. However, there has been no trend in the result of appeals. In particular, the proportion of cases discharged at appeal hearings has not changed substantially. Again, this replicates data from the 1980s (Reference Webster, Dean and KesselWebster et al, 1987). No association was found between the results of appeals and any demographic variable, including ethnicity. Only just over 1 in 10 hearings resulted in the section being lifted, which is consistent with other data. Mental health review tribunal data from 2000 to 2001 show that rates of discharge varied from 8.8% to 13.5% across different areas of England and Wales (Department of Health, 2002).

Although there are several studies confirming reports of greater than expected compulsory admissions of African-Caribbean patients (Reference Owens, Harrison and BoofOwens et al, 1991) and of patients from other ethnic minority groups (Reference Thomas, Stone, Osborn, Thomas and FisherThomas et al, 1993), our study did not reveal any association between the result of the hearing and ethnicity. Studies have shown detentions to have bimodal distribution with peaks at age 25-34 years and at over 80 years of age. In the younger age group, rates of detention were higher for men (Reference Audini and LelliottAudini & Lelliott, 2002). In contrast, the current data showed no linear association between age and hearing result and there was no association with male gender.

The study has several limitations. It was based on local data and therefore it gives information only about local trends. Trends in other areas and national trends may differ. Numbers of people in ethnic categories other than White were small and so the power of the analysis of ethnicity was limited. Similar considerations apply to the analysis of other demographic characteristics such as marital status, since only a minority of participants in appeals were married or in a long-term relationship. Nevertheless, the study presents important indications of a rise in the use of the Mental Health Act in one area and a rising volume of appeals against the use of this statute. Since the appeals are no more likely to result in discharge, it means that the rise in the use of the Act is not balanced by increased rates of discharge by review hearings. These trends may indicate that the Mental Health Act is being applied to people who are less severely ill and therefore more likely to appeal. In other words, the Act may currently be applied in more disputable situations, possibly more often with people who maintain the capacity to understand and challenge its use. However, any such change is not reflected in the results of appeal hearings. This may indicate that the threshold for discharge by appeal hearings has risen, in the same way and possibly for the same reasons that the threshold for detentions has fallen. Another factor could be that patients, like everyone else, are increasingly aware of their legal rights. The availability of advocacy services may have facilitated this.

The study also demonstrates the growing workload for all involved in Mental Health Act appeal hearings. This workload may increase after passage of amendments to the 1983 Act, since the introduction of compulsory community treatment orders may result in greater numbers of patients being made subject to the Act. Although the introduction of crisis resolution and home treatment teams may reduce admissions, indications are that these teams do not reduce compulsory admissions to a statistically significant extent (Reference Johnson, Nolan, Pilling, Sandor, Hoult and McKenzieJohnson et al, 2005).

The low rate of success of Mental Health Act appeals is not widely publicised. Patients should be informed about this before they embark on an appeal. We also need to think about whether the system is an adequate check on increasingly liberal use of psychiatric detention.

Declaration of interest

J.M. is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network, a group of psychiatrists that has campaigned against the expansion of the remit of the Mental Health Act and D.K.S. is a member of this network.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.