As part of the development of continuing professional development (CPD) for non-training grade doctors working in the field of mental health, the College has made a number of proposals to modify the CPD process (Reference Katona and MorganKatona & Morgan, 1999). A key proposal is the prospective planning of individual CPD requirements with local peer groups. CPD is defined, for the purposes of this paper, as continuing education of an individual throughout professional life with prospective planning undertaken in association with a peer group, this process eventually contributing to an annual appraisal. CPD, delivered in the context of clinical governance and revalidation, will have to meet the needs of both individuals and local services.

In order for CPD to be successfully implemented, potential obstacles must be identified and overcome (Reference Grant and ChambersGrant & Chambers, 1999). An often quoted barrier to successful introduction of new systems in health care is the resistance of doctors themselves (Reference GleinerGleiner, 1998). Knowing the views of those who have to undertake CPD, and how they might view difficulties with any proposed format, will aid in successful implementation. The aim of this survey was to determine how a group of non-training grade psychiatric doctors would view the proposed CPD format, with particular reference to the peer group planning method.

The study

A list of all non-training grade psychiatrists in the Wessex region was obtained from local CPD representatives. Each person on the list was then sent a questionnaire with an explanatory letter. The questionnaire asked respondents a number of questions concerning CPD, including the size of peer group and a possible frequency of meeting. Respondents were then asked to identify problems that might be anticipated with the peer review method, along with who should receive information from the process and possible penalties if the process was not satisfactorily undertaken.

Findings

In all, 189 non-training grade staff in psychiatric posts were identified in the Wessex region. Of these, 136 (72%) were consultants, 42 (22%) were staff grades and 11 (6%) associate specialists. The total number of respondents was 115 (60.8%). Ninety-four out of 136 (69%) consultants, 16 out of 42 (38%) staff grades and 5 out of 11 (45%) associate specialists responded. When asked whether respondents agreed with some form of CPD, 113 (98%) said they did, while two (2%) said they were against CPD.

When asked whether respondents were currently registered for CPD, 87 (76%) indicated they were. Of these, all associate specialists were registered for CPD, while 76 (81%) consultants were registered and only 7 (44%) staff grades. Of the 26 not registered for CPD, 15 (58%) intended to register, while six did not intend to register. Five did not specify their intention. When asked about who CPD should be planned with, a majority suggested peer groups, although a significant percentage also suggested other alternatives, such as medical director and manager. Respondents were then asked to specify the optimum number for a peer group. The vast majority of respondents indicated the optimum number in a peer group to be between three and six. The optimal frequency of meetings ranged between 2 and 12 months, with the mode being every 3 months.

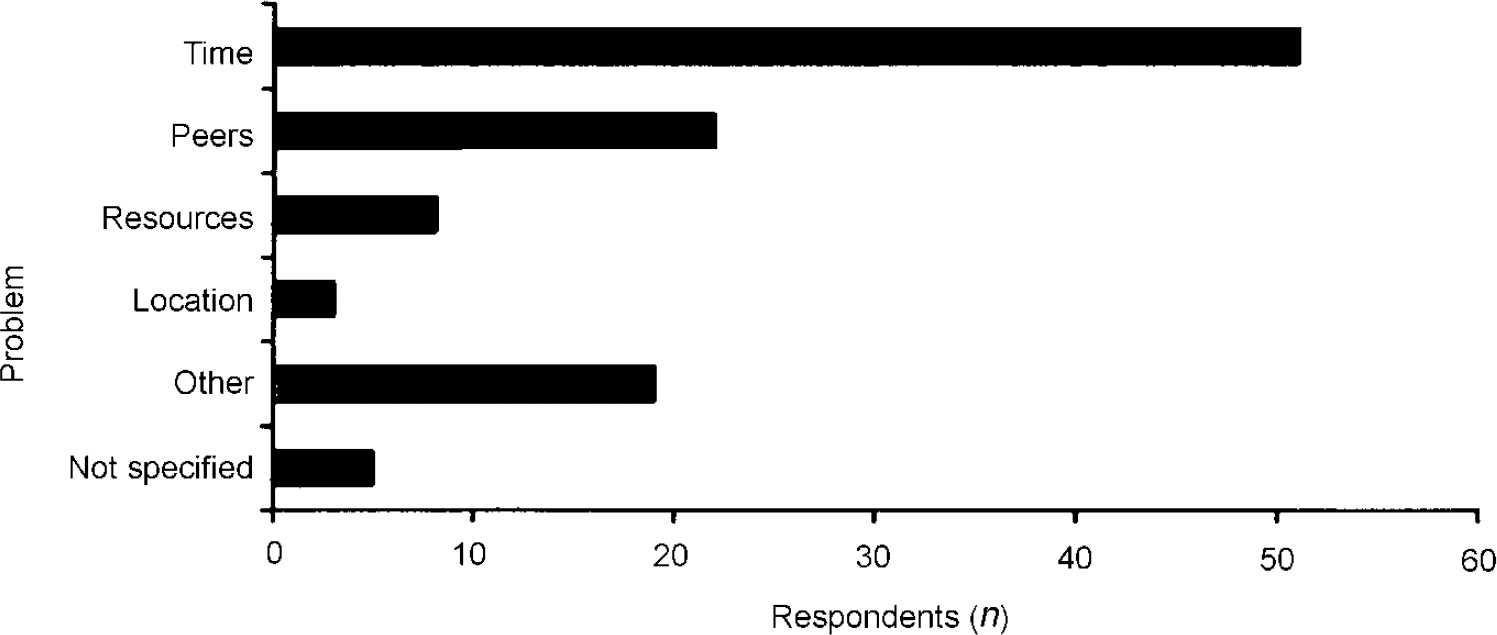

The next part of the survey asked respondents to comment on what the single most important problem would be with the peer review method. The three most likely problems cited were availability of time, peers themselves and resources generally (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Problems with peer the review method

Respondents were then asked how peers themselves could be a problem. From the responses three main problem areas were identified, as shown in Table 1, more than half being identified in the ‘individual’ category.

Table 1. Examples of potential problems identified with peers

| Individual | Speciality v. speciality | Peer group v. trust organisation |

|---|---|---|

| Not competent | Competition for courses | No authority to get resources |

| Uncooperative | Disparate | Coloured by local politics |

| No commitment to process | Difficulty in reaching consensus | Ineffective |

| Lack of trust | Lack of knowledge of other specialities | Different goals |

When asked who should receive information on this process, respondents demonstrated some uncertainty. One-fifth of respondents indicated either the college or medical director, with similar numbers suggesting a combination of the two. A number of alternative suggestions accounted for the other 40% of replies. Finally, respondents were asked to specify a penalty for not undertaking CPD. Again, a variety of answers were suggested, the three most common being loss of accreditation as educational supervisor, loss of individual accreditation and a combination of both.

Discussion

As government policy moves towards a more transparent process of quality control in health care, emphasis on the education of doctors becomes greater. For those in non-training grades, this education is provided in the form of CPD. The response to this survey implies that the vast majority who need to register will already have registered, although staff grade doctors may be one possible area of concern. Owing to varying rates of return, results would appear to be generalisable for consultant staff but not necessarily for staff grades and associate specialists.

In psychiatry, CPD will be prospectively planned with the aid of a peer group. However, from this survey, under half of respondents thought peer groups alone should be involved in CPD planning, while over a quarter thought peer groups should not be involved at all. Of those rejecting peer groups for CPD planning, a majority thought another key individual should be involved, such as the medical director or lead consultant.

Regarding peer group size, four was the most often quoted, with six to a group coming a close second. Three months was the most popular meeting interval, the second most cited being 6 months. Both the number in the peer group and the frequency are roughly in line with College expectations, that a peer group of two might be too cosy and more than six too ambitious, and meetings should be at least twice a year.

A number of potential problems were identified with the peer group method. Almost half of those surveyed identified time as being a difficulty. This is consistent with previous studies on CPD (Reference NewbyNewby, 1999). One-fifth thought peers themselves would be a problem. More specifically, three problem areas associated with peers were identified; relating to individuals within the peer group; problems between specialities represented within the group; and the relationship between the peer group and other bodies (see Table 1). Poor relationships within the group, for example lack of trust and cooperation, were seen as key difficulties. Similar comments were made concerning relationships between specialities, with lack of mutual understanding and difficulties with consensus being examples. This might be exacerbated by some specialities being underrepresented in a locality, either through vacant posts or through lower workforce requirements. Finally, there was concern over potential for conflict between peer groups and other organisations, for example, over resource allocation and different goals, particularly when peer group decisions are contrary to local or national policy.

The last part of the survey asked about the sharing of information from the peer group process, and the possible penalties for not complying with CPD requirements. Interestingly, only 40% of respondents thought the College should receive the information, while the medical director was cited in half of the replies. Yet CPD will be an integral part of the annual appraisal process in which medical directors will have a key role (British Association of Medical Managers, 1999) and the College will need to be involved in the process of certification.

Regarding possible penalties, over half of respondents cited “loss of accreditation as educational supervisor”, either alone or with another penalty, as the most ‘desirable’ penalty. However, currently this only relates to consultants. Loss of individual accreditation was considered an option in only 10% of respondents. This is at odds with the intention of the General Medical Council to introduce revalidation for all doctors (Reference BuckleyBuckley, 1999). CPD will play a crucial role in this process, with failure to comply almost certainly resulting in loss of accreditation.

This survey demonstrates that participants in CPD show clear preferences for the way in which CPD is designed and implemented. These preferences may not necessarily reflect national or local CPD policy, either in method or in potential implications if CPD fails in individual cases. These findings suggest that, along with the provision of appropriate resources, the participation of those undertaking CPD should be actively sought at every stage if the implementation of CPD is to be successful.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Brenda Holmes and Eileen Jay for their invaluable help in collating the survey data.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.