This paper gives an outline of four research areas examining therapeutic community practice: an international systematic review, health economics cost-offset work, a cross-institutional multi-level modelling outcome study and a proposed action research project to deliver continuous quality improvement in all British therapeutic communities. Results of the first two have been published and are summarised here; the third is under way and the fourth is seeking funding.

Therapeutic communities in mental health service settings date back to World War Two (Reference MainMain, 1946; Reference KennardKennard, 1999) and have a long history of research endeavour (Reference Lees, Campling and HaighLees, 1999). However, most of the early work is descriptive or qualitative. A few contributions stand out, such as Robert Rapoport's Community as Doctor, which was published as a book in 1960 and described four ‘themes’ by which therapeutic communities have become known; permissiveness, reality confrontation, democratisation and communalism. The study used an ethnographic and questionnaire method at Henderson Hospital, and analysed the data using a grounded theory approach to distil the ‘themes’.

In the past few years the Association of Therapeutic Communities (ATC) has formed a committee to co-ordinate research in a way that meets modern demands for high quality evidence (Department of Health, 1999), while keeping mindful of the democratic and consensual way in which therapeutic communities necessarily work. The studies discussed here have all been developed in consultation between therapeutic communities, in this committee. It does not include the extensive qualitative and quantitative research undertaken recently in prison units run as therapeutic communities (see for example, Reference MarshallMarshall, 1997; Reference RawlingsRawlings, 1998).

The international systematic review

A systematic international review was commissioned by the late High Security Psychiatric Services Commissioning Board (HSPSCB) in 1998 and published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York (Reference Lees, Manning and RawlingsLees et al, 1999).

Their working definition of a therapeutic community was: “A consciously designed social environment and programme within a residential or day unit in which the social and group process is harnessed with therapeutic intent. In the therapeutic community the community is the primary therapeutic instrument.” They did not attempt to address issues of defining personality disorder per se, noting that it was a term subject to sociological drift over the past 2-3 decades, over which time the studies reviewed were performed. Examples of figures from some of the units gave 87% of members meeting DSM—IV—R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD), and 95% meeting criteria for at least one cluster B Axis II diagnosis; these are patient groups familiar to psychiatric and psychotherapy services.

In addition to research literature, they targeted the grey literature by writing to known therapeutic communities, writers and workers in the field, asking for any published and unpublished research they had and information about their principles, organisation and practices. The work was conducted in accordance with the guidelines from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination — using protocols for searching and criteria for describing relevance and quality of identified research. Systematic meta-analysis was only possible for part of the results, as much of the literature was not numerically comparable.

They began with 8160 papers and reduced this to 294 broadly covering the relevant area. One hundred and eighty-one therapeutic communities were named in 38 countries. There were 113 items on outcome studies (72 in secure settings, including 20 addiction units). Of those 113, 52 were controlled: 10 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 10 cross-institutional and 32 other controlled.

A meta-analysis was undertaken, with 23 controlled studies excluded because outcome criteria were unclear; raw numbers were not reported or original sample before attrition was not clearly specified. Where there was a choice of outcome measures or control groups emphasis was placed on conservative criteria (like reconviction rates rather than psychological improvements) and on non-treated controls.

Of these 29, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (Cls) were calculated. Then odds ratios were combined into sub-sections and overall. The meta-analysis showed strong evidence for effectiveness: across all 29 acceptable studies, the summary odds ratio is 0.57 with an upper 95% Cl of 0.61. Other groupings — like all the RCTs and the 3 different subgroupings of therapeutic communities all show strong results with upper Cls well below one. This shows that no one subset of studies was strongly affecting the overall summary result.

Considerable efforts were made to try and avoid publication bias from negative results being not submitted or published but little grey literature was found. Odds ratios were plotted against sample size in a ‘funnel plot’. The lower the sample size, the higher should be the odds ratio reported, giving a funnel shaped scattergram. The exception is that a scattergram would reveal blank spots caused by unpublished findings, or ‘lost’ studies. The funnel plot for this meta-analysis does not suggest that this is the case.

The highest level of rigour, or ‘type la evidence’, as defined in the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999) is “at least one good systematic review, including at least one RCT”. The answer to the question “do therapeutic communities work for personality disorder?” is therefore clearly yes. This systematic review went on to make several recommendations for further types of study and reducing dropouts. One of the RCTs reported ran into major problems with attrition and contamination between the two limbs, and the cross-institutional design was suggested as a more promising methodology for future studies, although more complex in methodology and less definitive in results.

Cost-offset work: the health economics analysis

A Henderson study (Reference Dolan, Warren and MenziesDolan et al, 1996) examined a cohort of 29 admissions, of whom 24 were followed up 1 year after treatment. Service usage was assessed for psychiatric in-patient, day-patient, out-patient and periods of imprisonment. The average cost of treatment at Henderson was £25 461 per patient. Total psychiatric and prison costs for the year before treatment were £335 196 and £31390 for the year after treatment. This was calculated as an average cost-offset of £12 658 per patient, which if maintained would mean the Henderson treatment would pay for itself in just over 2 years.

A more recent study at Francis Dixon Lodge in Leicester (Davies et al, 1999) looked at 52 consecutive admissions, and examined histories of in-patient admissions for 3 years before and 3 years after admission to the therapeutic community. Psychiatric bed use dropped from 74 per year to 7.2 for the patients referred from outside the district, and from 36 per year to 12.1 for those locally based. This represents an average cost offset of £8 571 over 3 years following treatment.

A Cassel Hospital cost-offset study (Reference Chiesa, Iccoponi and MorrisChiesa et al, 1996) compared 26 consecutive admissions to 26 in a post-treatment group. Although, for that and other reasons, it was methodologically less exacting, they estimated a cost offset of £7423 per patient. A comparative trial at the Cassel Hospital (Reference Chiesa and FonagyChiesa & Fonagy, 2000) has shown that patients with personality disorder treated with a 1-year in-patient programme significantly improve on symptom severity, social adaptation and global assessment of mental health, while there is limited improvement on some clinical indicators of outcome such as self-harm, parasuicide and readmission rates. However, those on a shorter in-patient programme followed by psychosocial outreach nursing and continuing group therapy fare even better, and significantly so. A third limb has been added to the study, a comparison group in North Devon who receive community mental health team care as usual, and they show no improvement or very limited improvement on all outcome measures (Chiesa, 2001, personal communication).

An extension of the cost-offset argument would be to claim that a number of these patients do not need residential treatment, and there would be clinical and social advantages to treating them without removing them from their normal environment — in locally accessible day units. The costs of treatment in such units would be significantly less, and rehabilitation could be designed as an integrated part of the programme. The development and use of such modified therapeutic communities, including outreach elements and treatment in day units, has been proposed (Reference HaighHaigh, 2000; Reference Haigh and SteganHaigh & Stegan, 1996).

The cross-institutional multi-level modelling study

The cross-institutional study is funded by the National Lottery Charities Board, and started in late 1999. It is addressing four research questions in a 25-centre UK project (ATC, 1999):

-

(a) Who uses therapeutic communities?

-

(b) What are the distinctive treatment elements?

-

(c) How do therapeutic communities vary?

-

(d) What is related to good outcome?

The analysis is multi-level modelling, as used in education. In schools, for example, numerous factors are analysed at the level of individual pupil, class, school and county. In this study, natural variations in process and outcome in the 23 communities are measured, and a path analytic causal model of the interaction between the constituent parts of the process and outcome is constructed. A qualitative component will be used to refine understanding of the treatment elements, at three representative therapeutic communities. It will be triangulated by using ethnographic observation and semi structured interviews.

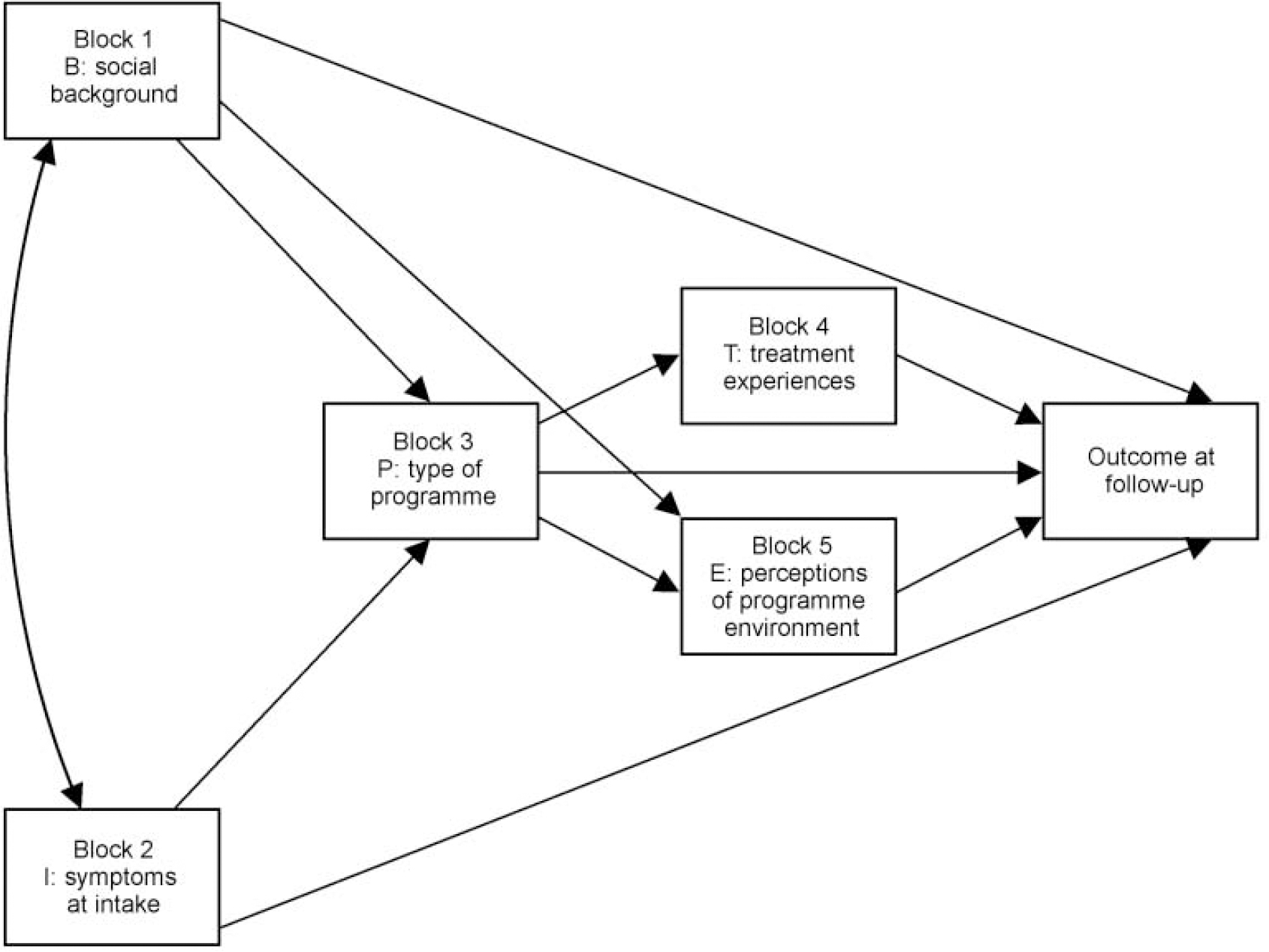

The individual subjects of the study will be the total population in the participating therapeutic communities, investigated seven times — typically every 3 months for 18 months. The study needs 200 participants to achieve sufficient power to give adequate precision for path analysis. Six areas are measured: individual subjects' social backgrounds and initial symptoms, the programmes they are in, their experiences and perceptions of those programmes and outcome at follow-up. Figure 1 shows the probalistic ‘strength’ of causality between each of the component parts.

Fig 1 A model of treatment outcome

An action research proposal: sharing best practice and valuing diversity

The protocol for an action research project has been drawn up by the Clinical Governance Support Unit at the College's Research Unit (CRU). This is in collaboration with ATC and the Charterhouse Group (CHG, specifically representing therapeutic childcare). It will be in the form of a ‘quality network’ (ATC, 2000).

A set of service standards is being developed as the first stage of the process. This will involve all participating communities, their users and have input from commissioners, referrers and others. It will be reviewed annually in the light of new policy and practice developments and feedback from the reviews. The aim is that it will set up an open and democratic definition procedure, with involvement of all those who have a legitimate interest, and an agreed method for reaching decisions.

Once the initial standards have been written, the process will involve annual reviews; alternately internal (by a community's own staff and users) and external (with visitors). For the external reviews, the visiting team (staff and service users from a therapeutic community elsewhere, with a methodologist) will spend a full day on the visit. It will provide an important learning experience for reviewers as well as the service being visited. Reviewers will be trained in the use of the standards.

The results of both internal and external reviews will be collated and disseminated. Detailed individual feedback will be given about activity against the standards, in comparison with other community members of the network (national benchmarking) and in relation to the communities' activity in previous reviews.

The model will be one of engagement rather than of inspection. The expectation will be that therapeutic communities who are network members will use the results of reviews to achieve year on year developmental change. They will be expected to share their results with key groups locally, including health and local authorities, those making referrals to their service and local user and carer groups. Where difficulties in communities become apparent, action planning workshops involving other network members will be set up to help services develop and implement plans based on the findings of reviews.

In the longer term, the project should be able to identify the necessary supporting structures to ensure therapeutic communities are effective services of high quality. This might include development of specific training programmes for both individuals and staff teams, career structures to allow movement between different types of therapeutic community and a consequently agreed research strategy. An early example might be the incorporation of results from the cross-institutional study (described above) into the standards: robust results about what matters in therapeutic communities will be discussed at a stakeholder conference and incorporated by the democratic process.

This is more than an audit cycle because it will be producing new knowledge (about what defines a therapeutic community, and what is good practice within one) and bringing about structural change in systems (new ways of doing things). It is an action research project because it will gain its legitimacy through a consensual process involving all involved parties: all the stakeholders ‘own’ the emerging results. It is a coherent way of ensuring and improving quality while bringing about coordinated and research-based change. Further-more, it institutionalises the process of change, so therapeutic communities become responsive to the superordinate systems upon which they rely for survival. They will need to continually negotiate their place among other communities and other treatment modalities by maintaining a culture of enquiry (Reference MainMain, 1967; Reference NortonNorton, 1992) about their own practice.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.