Formerly Consultant Psychiatrist, St Nicholas Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne

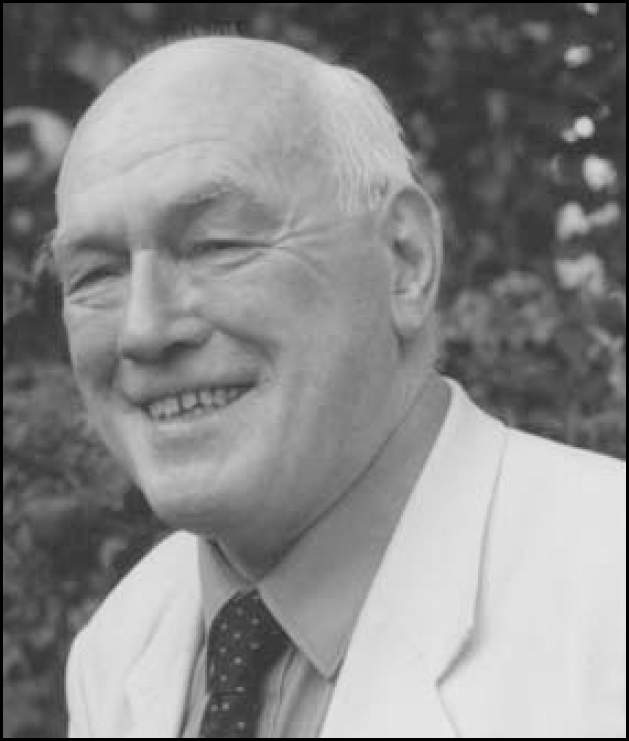

Peter Morgan was born on 28 November 1928 in Bishop Auckland, County Durham.

An intelligent and politically motivated student, he went to Kings College, Durham University, which was at Newcastle upon Tyne. Keen to alleviate the plight of coal miners in the optimism of post-war technology, he first studied physics, but gravitated towards medicine as a more potent force for social change. Locally, he became chairman of the Liberal Society, set up a free trade organisation, acted as president of the Medical Students Union, vice president of the British Medical Students Association and, briefly, president of Durham University Students Council.

He was frustrated at the false mind-body dualism in medicine, and it so happens that, while working at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle upon Tyne, he noted the use of surgical interventions for what would now be considered irritable bowel syndrome; he decided to study psychological medicine. His enthusiasm was intensified by the appointment of Sir Martin Roth as Clinical Professor at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Sir Martin became his lecturer and, subsequently, consultant colleague for the next 20 years. Sir Martin's ability to combine science, art and humanity inspired Peter for the duration of his career.

Peter formed the opinion that a significant number of patients in vast psychiatric hospitals would be better accommodated within the community, and this opinion coincided with the initial wave of replacing 1000-bed mental hospitals with smaller units. He took great pleasure and satisfaction in this process, working tirelessly to overcome local bureaucracies with any tools at his disposal, including political influence in local planning departments and alliances with Quakers, the Salvation Army and Mind. It was typical of him that the death of his baby daughter Diana, from complications of Down syndrome, led him to establish some of the first training centres for people with learning disabilities.

Peter settled as a consultant psychiatrist at St Nicholas Hospital in Gosforth and also became Medical Director of the newly opened Lindisfarne Suite Psychiatric Unit which flourished under his leadership. He succeeded because he hugely enjoyed his profession which he regarded as a privilege. He practised continually for 50 years and resented his necessary retirement, aged 76. An influential clinician, he was more of a ‘patient's doctor’ than a ‘doctor's doctor’, and was admired by his patients for his devotion, wit and wisdom. As Peter's health declined, it is indicative of the affection he inspired that so many of his erstwhile colleagues became his carers, including his nursing staff and his medical secretary. Predeceased by his wife, Anne, he died at home on 23 May 2008 in the presence of his grandchildren and carers. Following his death, he was credited in the local press as having ‘changed the way we deal with mental illness’.

He left behind three children; the author of this piece (also a consultant psychiatrist), a solicitor and a clinical psychologist, as well as nine grandchildren.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.