In 2004 Buckinghamshire Mental Health Trust set up a crisis and home treatment team. This team functioned alongside the local Trust day hospital, which had been upgraded to an acute day hospital with the remit to minimise hospital admissions and facilitate early discharge. By February 2006 the Trust recognised that the acute day hospital and crisis and home treatment team were performing similar functions and therefore should be co-located; and, as Buckinghamshire geographically is a long thin county from north to south, it was appropriate to re-deploy into two bases in the north and south. The service was ‘re-launched’ as the community acute service, complete with one whole time equivalent consultant and junior to provide the (previously) missing medical input. Notably, the Department of Health Mental Health Policy Implementation Guidelines 1 was used as the operating model for the crisis and home treatment team element of the new service.

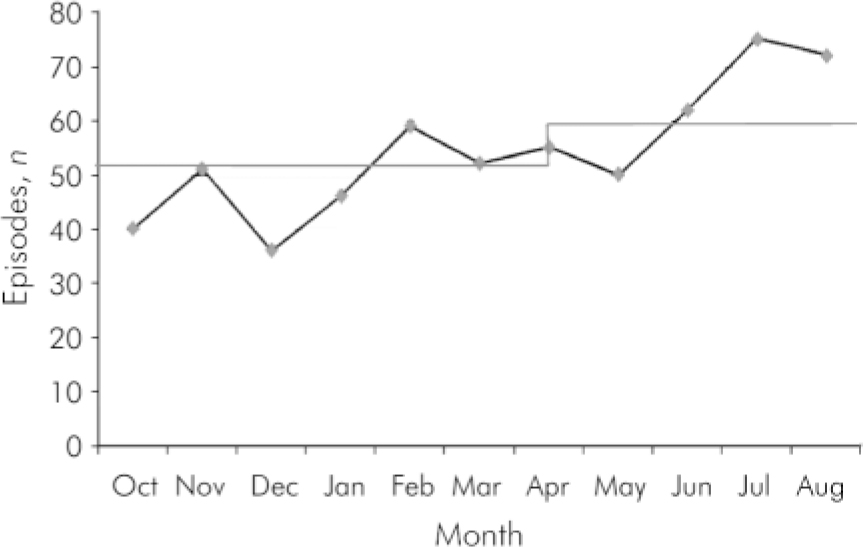

In spite of the vision for an integrated community acute service team, after a 6-month review it became clear that the two component parts (the crisis and home treatment team and the acute day hospital) sat uneasily together. The crisis and home treatment team was adhering rigidly to the Department of Health guidelines, 1 leading to continual problems with people suffering rejection against access criteria; at the same time the team had difficulties fulfilling its service level agreement (Fig. 1). A lack of clarity in clinical pathways and roles regularly led to arguments as to who should be looking after patients, and complaints from service users and allied health services were commonplace.

Method

Defining the problem

The initial mandate (by S.M.) was to look at crisis and home treatment team functioning; this involved shadowing team members to observe their working patterns, followed by consultations with W.B. and D.A. (who was involved with the acute day hospital from the outset). It was agreed that in order to provide a value-based service to patients and at the same time meet the Trust's targets, a model of seamless care between the crisis and home treatment team and the acute day hospital was the best way forward.

Fig. 1. Buckinghamshire community acute service episodes, October 2006 to August 2007. Target adjusted to reflect wider geography and corresponding additional headcount.

S.M. advised to focus first upon the development at the level of the ‘core competency’ (systems and processes of delivering care). The first step was to start to improve the capacity of staff by freeing up their time, and next to increase their ability by training and supervision. Finally, methods would need to be developed to reduce variation in the way that the service addressed demand emanating from its referrers.

The study's aim was to answer the following questions:

-

• capacity: what time is lost unnecessarily and how much wasted activity is there?

-

• sources of demand and activity (looking for ways to smooth demand and reduce unnecessary activity);

-

• sources of variation in service delivery: can we identify the causes of variation and how do we eliminate them?

-

• service delivery: how should the service organise itself in order to deliver what had been commissioned and how did it define the purpose of the service?

Finding solutions

Solutions to lost capacity (i.e. time spent travelling to distant wards or addresses in order to observe arbitrary, geographical boundaries when the sister community acute service could get there in less time) emerged from observations of the team at work and from the analysis of both Trust-held and locally generated data. Once goals were identified, changes were agreed and made by the lead consultant and service manager in consultation with Trust management.

Options for service reorganisation flowed first from the studies described above and second from patient case reviews conducted between key community acute service clinicians and their ‘internal customers’ (community mental health teams (CMHTs), wards, and accident and emergency departments). The philosophical underpinning of all solutions was the concept of ‘lean systems’. This can best be summarised as removing all the steps in the delivery of care which are of no value to the patients or other ‘customers’.

Results

Generic changes

It is not possible in this article to cite all the changes that have resulted, but key examples are listed below.

The northern team, which was co-located with the wards, took over in-patient assessments and the southern team would take on an extra CMHT to reduce overall travel time.

It was agreed that reassessment by the community acute service of people known to CMHTs was unnecessary and that instead time should be spent formulating agreed care plans. Reassessment was only needed in complex cases, particularly those involving personality disorder.

Junior doctors in accident and emergency were empowered to identify and manage psychiatric attendees who were not in need of secondary services by the use of a screening tool for depression and a questionnaire that enabled them to identify which patients were already in touch with our services. This reduced the number of out-of-hours calls and enabled us to concentrate on home treatment.

A care model emerged based on a single community acute service keyworker but with two sub-teams: the crisis and home treatment team and the acute day hospital. Twice-weekly whole-team meetings made it possible for people to have treatment in the acute day hospital, at home or both at various points in their journey through the service.

Continuous adjustments to the Trust's information system and the move to a single currency to count activity in both the crisis and home treatment team and the acute day hospital, led to a reduction in errors in performance figures. It also improved the quality of the collected data and significantly reduced the overall inputting time.

More focused care planning and earlier referral to CMHTs meant that flow through the system improved. It was agreed that during the day the duty CMHT would start any assessments and that after hours the community acute service would take over, leaving them free to provide home treatment during the day.

The community acute service also committed to working with people, even if it only meant doing so for short periods before returning them to CMHTs or general practitioners (GP). Where people needed hospital admission, the community acute service facilitated this by ‘tracking’ their progress for early discharge.

The more efficient running of the service as a whole has enabled the Trust to cope in the face of the closure of one of the acute adult wards. Some of the nursing staff from this ward chose to join the community acute service; this combined with newly recruited staff greatly increased the team's capacity and enabled us to work in a much more assertive way. A good example of this was increased visits to the acute day hospital non-attendees at home, thereby switching easily between the different modes of delivering care.

Patient typing

Good patient outcomes depend on identifying what it is individuals really need to get better. The most innovative change in our project was to identify that need in a proactive manner and ‘label’ it. We developed six ‘service types’. Types A and B were about mental illness, in the community or in an acute day hospital respectively; it soon became evident that many people would need both at various stages.

Individuals with dual problems, for example substance misuse or learning disability, were classified as type C: their extra needs are for linking in with other services and sometimes in more direct ways than current practice allowed. The emphasis is on configuring help around the individual, not referring them away for some aspect of their care. For example, we can detoxify people from alcohol and bring the substance misuse team into the acute day hospital to see them there.

Type D refers to people who present with an acute crisis and no mental illness; they are dealt with in a more holistic way, with minimal medical input and are able to return back to their GP or CMHT fairly quickly. People with more prominent personality difficulties can be signposted to our complex needs service if appropriate.

Sometimes we encounter people who might not have been appropriate for our service, but who present out of hours; these people are termed type E and we ‘keep them safe’ until they can be passed onto another service. Type F refers to purely elective ‘admissions’, usually to the acute day hospital, for medication switches, classically to clozapine.

With early discharge from hospital we developed the concept of ‘trial leave to the community acute service’ to deal with the uncertainty we all sometimes feel about a individual's treatability in the community. Leave is granted until the date of a future community acute service clinical meeting when a team decision is made and the ward informed. For individuals still detained under the Mental Health Act, the community acute service consultant then becomes the responsible clinician.

Discussion

We know that home treatment is an effective intervention Reference Smyth and Hoult2 and reduces hospital admission rates by about 23% for 24-hour services. Reference Glover, Arts and Babu3 Additionally, home treatment is generally preferred by patients. Reference Smyth and Hoult2 Similarly, we know that certain carefully selected individuals with severe mental illness improve more quickly in a day hospital than if cared for as an in-patient Reference Marshall, Crowther, Almarez-Serrano, Creed, Sledge and Kluiter4 and that acute day hospitals provide greater patient satisfaction than in-patient care, at least in the short-term. Reference Priebe, Jones, McCabe, Briscoe, Wright and Sleed5

One of Marshall's Reference Marshall6 proposals for developing day hospital care was to combine it with outreach services for people who fail to attend. Our model has started from the same ‘structures’ but our philosophical approach has been to tailor the care to what patients value most. Working as one team, the crisis and home treatment team and the acute day hospital are able to design flexible care plans, switching easily between modalities of care with minimal bureaucracy, creating a whole much larger than the sum of its parts.

From a service management point of view, the team is now fulfilling its service level agreement; increased efficiency has also facilitated a reduction of in-patient beds. Early polling suggests high user satisfaction and the team is committed to collecting continuous feedback through market research-style questionnaires; these will be used to inform future improvements. One of the areas we are currently working on is improving the interface with other services.

Declaration of interest

S.M. runs his own company, which works specifically with mental health services to improve their performance.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.