The Department of Health requires that specialist early intervention services be introduced throughout England (Department of Health, 2001). One of the goals of such services is to improve acceptability and thus to increase long-term engagement. In-patient services currently appear unpopular with mental health service users in the UK (Reference Greenwood, Key and BurnsGreenwood et al, 1999; Reference RoseRose, 2001). When the initial experience of mental health services by people with psychosis is hospital admission, this may reduce long-term willingness to engage.

Studies in areas without early intervention services or services offering intensive home treatment have found high rates of admission among people with first-episode psychosis, ranging from 80% to 95% (Reference Bhugra, Leff and MallettBhugra et al, 1997; Reference Castle, Wessely and VanosCastle et al, 1998; Reference Sipos, Harrison and GunnellSipos et al, 2001).

There is evidence of lower rates of in-patient admissions where specific early intervention services exist (Reference Power, Elkins and AdlardPower et al, 1998; Reference Malla, Norman and ManchandaMalla et al, 2002; Reference Sanbrook, Harris and ParadaSanbrook et al, 2003; Reference Yung, Organ and HarrisYung et al, 2003). In Melbourne the rate of hospitalisation within 3 months fell from 86% to 63% following the introduction of a specialist early intervention service (Reference Power, Elkins and AdlardPower et al, 1998). Admission rates as low as 54% have been reported when specialist early psychosis services are supplemented by crisis services (Reference Cullberg, Levander and HolmqvistCullberg et al, 2002).

A goal for early intervention services in England is to provide intensive community care following first contact with services in order to prevent admission. However, the NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2001) also requires crisis resolution teams to offer 24 h emergency assessment and intensive home treatment. Therefore, an important question for service planning is whether crisis resolution teams are capable of preventing admissions in early psychosis, thereby reducing the necessity for early intervention services to provide intensive home treatment.

Tomar et al (Reference Tomar, Brimblecombe and O'Sullivan2003) investigated service use by patients with early psychosis referred to a crisis resolution team and found that about half were successfully managed at home. However, the study sample was small (n=40) and did not include all presentations of first-episode psychosis in the catchment area. The aim of our study was to investigate the initial treatment phase of an epidemiologically representative cohort of patients with first-episode psychosis in a defined catchment area, focusing on the extent to which well-established crisis resolution teams were able to avert admissions during the first 3 months following initial contact.

Method

Setting

This study took place in the London boroughs of Camden and Islington, which have a combined population of 373 817 (2001 Census; http://www.statistics.gov.uk/census). The area is ethnically diverse and socially deprived and its population is skewed towards younger age-groups. The first local crisis resolution team was established in 1999 and at the time of the present study, four were in operation, providing crisis assessment and intensive home treatment throughout the two boroughs.

The Camden and Islington crisis resolution teams follow the guidelines in the Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide (Department of Health, 2001) and appear to be effective in reducing admissions in the weeks following a crisis (Reference Johnson, Nolan and HoultJohnson et al, 2005a ). They have a gatekeeping role, so that no patient can be admitted to hospital without an initial screening by the local crisis treatment team to determine whether home treatment is feasible. They are available 24 h a day and can offer visits at least twice daily when needed. The Islington crisis resolution teams have been the subject of a major research programme but the present study did not coincide with recruitment for either of the main evaluative studies (Johnson et al, Reference Johnson, Nolan and Hoult2005a ,Reference Johnson, Nolan and Pilling b ).

The area also has 24 h staffed crisis houses and well-established community mental health teams, integrating both National Health Service and social care professionals. At the time of this study, there were no specialist services for first-episode psychosis in the area.

Patients

In order to identify all new presentations of psychosis throughout a 1-year census period (2002), a researcher (M.G.) maintained contact with a range of key informants, including psychiatrists and team managers in the crisis resolution teams, in-patient wards, crisis houses, community mental health teams and accident and emergency liaison teams. Contact was made with all key informants at least once a month to confirm identification of any new presentations.

All patients were residents of Camden and Islington and were under 65 years. All those initially identified by staff as potential cases were screened using the World Health Organization Screening Schedule for Psychosis (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992). The Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Disorders (OPCRIT; Reference McGuffin, Farmer and HarveyMcGuffin et al, 1991) was then used to confirm whether criteria for an ICD–10 diagnosis were met (World Health Organization, 1993). All psychotic illnesses were included (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, depression with psychotic symptoms and mania with psychotic symptoms). Patients with an organic brain disorder were excluded.

Socio-demographic details and data regarding the individual’s initial assessment and pattern of care were collected from medical notes and from interviews with primary and secondary care staff using a standardised audit tool. Information regarding informal and formal admissions within the first 3 months was also collected using this tool.

Results

Between January and December 2002, 111 people with first-episode psychosis were identified. This represents an incidence rate of 30 per 100 000 population per annum.

Care following initial assessment

Table 1 shows the care provided following initial assessment for all 111 people. Sixty (54%) were admitted to hospital immediately (41 under the Mental Health Act 1983 and 19 voluntarily). Thirty-three (30%) were managed by the crisis resolution team and 18 (16%) by other community mental health services (11 by the community mental health teams, 5 by the out-patient clinic and 2 by child and adolescent services).

Table 1. Care planned following initial assessment of 111 people with first-episode psychosis

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Follow-up by crisis resolution team | 33 (30) |

| Compulsory admission to general adult ward | 30 (27) |

| Informal admission to general adult ward | 17 (15) |

| Follow-up by community mental health team | 11 (10) |

| Compulsory admission to psychiatric intensive care unit (in-patient) | 10 (9) |

| Follow-up in out-patients by psychiatrist | 5 (5) |

| Follow-up in community by child and adolescent mental health services | 2 (2) |

| Informal admission to child and adolescent in-patient ward | 2 (2) |

| Compulsory admission to child and adolescent in-patient ward | 1 (1) |

Socio-demographic characteristics and management

A comparison was made between the characteristics of patients initially taken on by the crisis resolution teams, those who were admitted immediately and those managed by other community services (Table 2). In all groups, most patients were single and unemployed, but the numbers living with family were greater than in inner city samples with established mental illness (Reference MacDonald, Jackson and HayesMacDonald et al, 1998). Those initially managed by the crisis resolution team were younger than the groups who were admitted or managed by other community services. Otherwise no significant differences emerged, although there was a trend for those admitted to be more likely to live alone than those managed in the community.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of the 111 people with first-episode psychosis according to initial management

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Crisis resolution team n (%) | Community mental health team n (%) | In-patient unit n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age1 | ||||

| < 17 | 5 (15) | 2 (11) | 4 (7) | 11 (90) |

| 18-24 | 15 (46) | 7 (39) | 23 (28) | 45 (41) |

| 25-34 | 11 (33) | 1 (6) | 19 (32) | 31 (28) |

| 35-44 | 2 (6) | 6 (33) | 6 (10) | 14 (13) |

| 45-54 | — | 2 (11) | 4 (7) | 6 (5) |

| > 55 | — | — | 4 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 21 (64) | 9 (50) | 40 (67) | 70 (63) |

| Female | 12 (36) | 9 (50) | 29 (33) | 41 (37) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 17 (52) | 7 (39) | 34 (57) | 58 (52) |

| Black British/Caribbean | 5 (15) | 4 (22) | 9 (15) | 18 (16) |

| Black African | 6 (18) | 1 (6) | 13 (22) | 20 (18) |

| Black other | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | — | 2 (2) |

| Asian | 4 (12) | 2 (11) | 4 (7) | 10 (9) |

| Other | — | 3 (17) | — | 3 (3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 28 (85) | 17 (95) | 54 (90) | 99 (89) |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 6 (18) | 4 (22) | 23 (38) | 33 (30) |

| With others | 27 (82) | 14 (78) | 37 (62) | 78 (70) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 21 (66) | 16 (89) | 41 (68) | 78 (70) |

| Employed/in education | 10 (31) | 1 (6) | 19 (32) | 30 (27) |

| Not known | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | — | 3 (3) |

Patterns of admission at 3 months

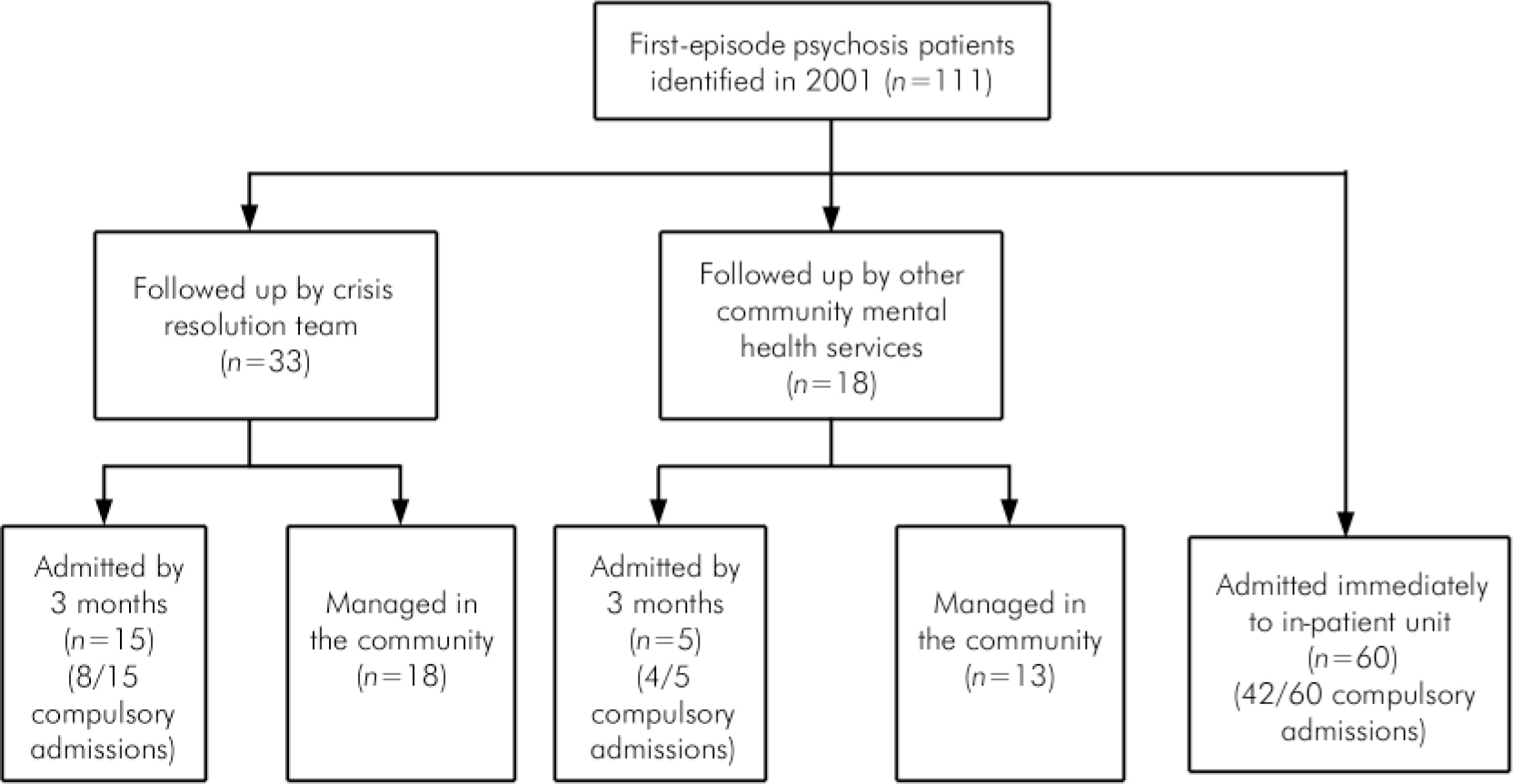

Figure 1 shows patterns of admission in the 3 months after the initial assessment. By 3 months, 80 people (72%) had been admitted and almost half (49%) had been detained compulsorily under mental health legislation. None had been admitted to the local crisis houses. For those admitted voluntarily after a delay, 7 were initially managed in the community by a crisis resolution team and 1 in an out-patients department by a psychiatrist. Of the patients initially treated in the community but later compulsorily detained, a crisis resolution team initially managed 8 and follow-up by a community team was the initial plan for 4. Of the 33 initially taken on by crisis resolution teams, 18 (55%) remained in the community throughout the 3 months whereas 13 of the 18 (72%) managed by other services remained in the community.

Discussion

The strength of this study is that it was conducted in an area with well-established crisis services, allowing assessment of how far a service network that includes these can prevent admission in first-episode psychosis. Data were obtained regarding every presentation of first-episode psychosis identified during the study year. Limitations of our study include the relatively small numbers, a catchment area whose socio-demographic characteristics make it an outlier nationally and the fact that there was no control group.

Our data support previous findings that admission rates are high and compulsory detention frequent among people with first-episode psychosis (Reference Power, Elkins and AdlardPower et al, 1998; Reference Garety and RiggGarety & Rigg, 2001; Reference Yung, Organ and HarrisYung et al, 2003). In our study 60 people (54%) were admitted to hospital immediately, a figure which rose to 80 (72%) after 3 months. Sipos et al (Reference Sipos, Harrison and Gunnell2001) reported similar rates of admission in an area with conventional community mental health teams (53% at first contact; 80.7% at 3-year follow-up). The admission rates in our study were not much lower than in this previous study, despite the availability of well-resourced crisis resolution teams.

The crisis resolution teams initially accepted almost a third of patients but almost half of these had been admitted by 3 months, so that at 3 months only 18 people (16% of the cohort) had received support from the crisis resolution team and had remained in the community. This and the high overall admission rate suggest that if crisis resolution teams do have an impact on admission rates in first-episode psychosis in an inner city area, it is probably modest. This might result from many patients being severely unwell and lacking insight by the time of presentation or reflect the fact that although intensive home treatment for early psychosis is one of the roles of crisis resolution teams, they are not specialists in this area. The study cohort did not make use of crisis houses, even though the area’s crisis houses do admit substantial numbers of patients with psychotic illnesses (Reference Killaspy, Dalton and McNicholasKillaspy et al, 2000). Crisis houses potentially offer care which is less stigmatising and more acceptable than conventional in-patient care: it is thus worth exploring whether the provision of crisis housing could play a greater role in the management of early psychosis.

The prevention of early admission may require the involvement of specialist services at a very early stage. Early intervention services should thus probably be involved immediately in assessments of people with first-episode psychosis rather than operating as a tertiary service (Reference Singh and FisherSingh & Fisher, 2004). An interesting question is whether such specialist teams, supplemented by contact with crisis resolution teams, will be able to prevent inpatient admissions for this group more effectively than crisis resolution teams alone (Reference Cullberg, Levander and HolmqvistCullberg et al, 2002).

Our data suggest that in-patient services remain for the present a necessary component of care for early psychosis (Reference Sipos, Harrison and GunnellSipos et al, 2001), even with the availability of intensive community treatment. Thus far most areas have set up only community teams for managing early psychosis and dedicated in-patient wards remain rare. If in-patient wards remain the first point of contact for many young people with psychotic illness, greater attention is required to making these more appropriate and acceptable than traditional in-patient services. Dedicated early psychosis in-patient services may be needed to achieve this.

Fig. 1. Service outcomes after initial assessment and admissions by 3 months.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.