When the Court of Appeal (COA) held that L. had been detained unlawfully the interpretation of the Mental Health Act changed dramatically (Department of Health, 1998). The informal admission of mentally incapacitated patients to mental hospitals became unlawful and with it a huge increase in the rate of sectioning became inevitable. Before the full effects of this had been seen, the House of Lords overturned the judgement. The grounds upon which the Law Lords overturned the judgement were principally that the Mental Health Act had been written with a libertarian intention and that the automatic detention of anyone with mental incapacity was not intended by the Act. Lord Goff (House of Lords, 1998) reminded us of the Percy Commission report (Royal Commission, 1957) which recommended “the offer of care, without deprivation of liberty, to all who need it and are not unwilling to receive it”. Lord Goff pointed out that the Court of Appeal's judgement suggested that “there will be an additional 22000 patients detained on any one day, plus an additional 48000 admissions per year under the Act”. This compared with a figure of 11000 detained under the Act at any one time prior to the COA judgement. It was also pointed out by Lord Goff that if the COA judgement were considered to apply to mental nursing homes not registered to receive detained patients, the estimates would be much higher. Lord Goff believed that L's readmission “did not constitute a deprivation of his liberty”. Rather care was provided to a patient whose illness had deprived him of the ability to choose under the doctrine of necessity.

Although the judgement was unanimously overturned, Lord Steyn (House of Lords, 1998) believed that the result was “an indefensible gap in our mental health law”. He said “the general effect of the decision of the House of Lords is to leave the compliant incapacitated patients without the safeguards enshrined in the Act of 1983” and lamented the fact that “the common law principle of necessity contains none of the safeguards of the Act of 1983”. He concluded by asserting that “there is no reason to withhold the specific and effective protections of the Act of 1983 from a large class of vulnerable mentally incapacitated adults. Some opinion at the time of the Lords ruling suggested, that the issue of mental capacity had come to stay, and that changes in practice which resulted from the COA judgement would be permanent and consolidate further (Reference EastmanEastman, 1998).

The UK government (Department of Health, 1998) issued guidelines after the House of Lords' ruling advising informal admission of compliant incapacitated patients but suggesting regular assessment of capacity during admission, consultation with relatives and/or carers, and visits by hospital managers or advocates if no-one from outside the hospital would otherwise take a continuing interest in their care.

The revised edition of the Mental Health Act Code of Practice (Department of Health & Welsh Office, 1999) has since been published and advises the informal admission of the mentally incapacitated and their treatment under the common law doctrine of necessity. Reference is made to consultation with immediate relatives and carers, but no other formal safeguards are recommended.

The study

We undertook a postal survey of consultant old age psychiatrists practising in the former South-East Thames NHS Region and also collected data on rates of detention from Mental Health Act managers in the same region. Census data on admissions of patients over the age of 65 years as well as patients detained at any one time were collected.

Findings

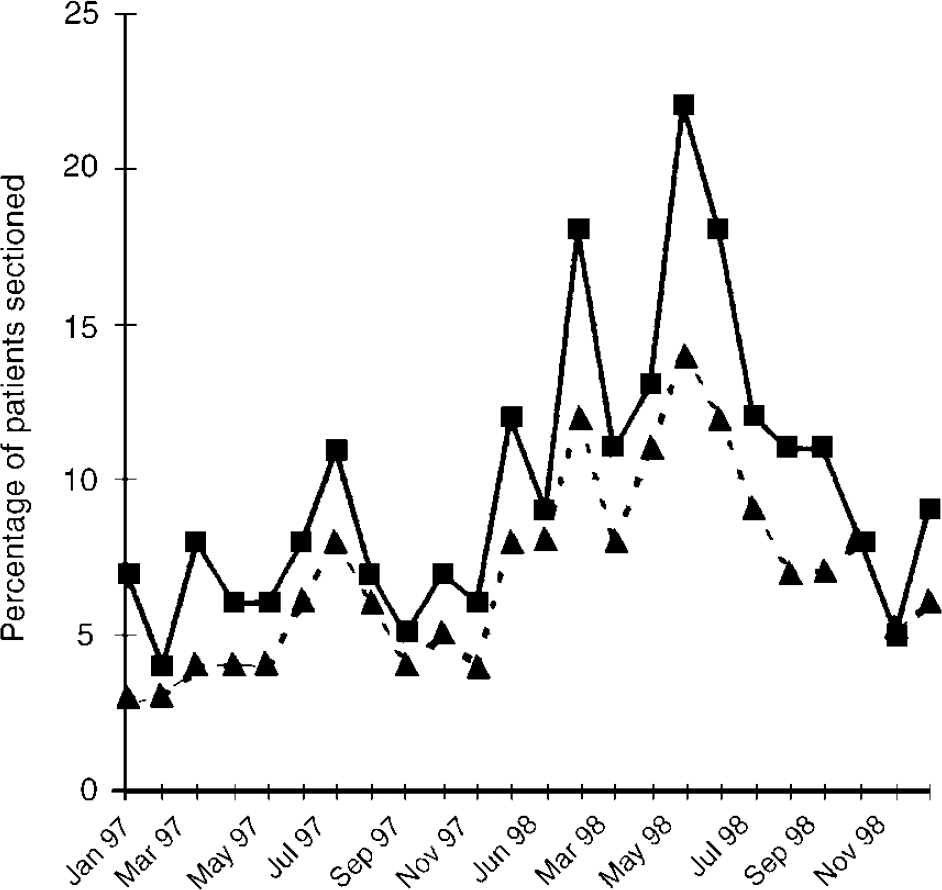

Twenty-six (72%) replies out of 36 questionnaires sent out were received from consultants. Responses to questions are shown in Table 1. Administrator's responses were available from seven hospitals and covered a total of 410 beds available for the assessment of the elderly. Figure 1 shows the percentage of all admissions under section on a month by month basis as well as cumulative data on the number of patients remaining detained. It should be noted that these changes appear to reflect alterations in the practice of some, but not all consultants.

Table 1. Consultant responses to questions

| Most favoured judgement | Court of appeal n=3 (12%) | Lords judgement n=22 (88%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did your rate of sectioning increase after the Court of Appeal judgement? | Decreased, n=1 (4%) | Stayed same, n=11 (42%) | Increased, n=14 (54%) |

| Since the House of Lords' ruling, what has happened to your rate of compulsory admission of patients with dementia? | Decreased, n=16 (62%) | Stayed the same, n=9 (35%) | Increased, n=1 (4%) |

| Do you now section more patients with dementia than you did before the Court of Appeal judgement? | Yes, n=6 (23%) | No, n=20 (77%) | |

| Do you think that it is satisfactory that patients without capacity are managed without any statutory safeguards? | Yes, n=7 (27%) | No, n=19 (73%) | |

| Has the Bournewood case had an impact for your future psychiatric practice? | Yes, n=11 (44%) | No, n=14 (56%) |

Fig. 1. Impact of Bournewood case on proportion of patients over the age of 65 years admitted under section, ▪, percentage of patients admitted under section; ▴, total percentage of patients under section.

Discussion

Over half of the consultants felt that their practice had changed as a result of the Bournewood judgement, but only a minority felt that the judgement still affected their practice. The majority of consultants agreed with Lord Steyn that the absence of safeguards for this group was not satisfactory. The data collected via Mental Health Act administrators show that the rate of detention was slow to increase following the COA judgement and this fits with the need to plan implementation of the COA judgement and the working groups which were established to do this at local level. By the time of the Lords ruling, the rise in detentions showed no sign of plateauing and it seems likely that detentions would have risen further had the judgement not been overturned.

Following the House of Lords judgement the detention rate appears to have returned to the pattern that pertained prior to the COA judgement. This suggests that the impact of the Bournewood case is now minimal and that the predicted permanent change in psychiatric care of the mentally incapacitated (Reference EastmanEastman, 1998) has not occurred. Even though around half the responding consultants felt that the judgement had had an impact upon their practice, there is no evidence of a continuing impact from the Bournewood judgement on clinical practice.

Although the Mental Health Act may not provide an ideal framework for the safeguarding of the mentally incapacitated, the effective absence of safeguards must, however, remain as concerning now as it was, last year, to Lord Steyn. At the present time in the UK, legislation is being considered that will change the management of the mentally incapacitated. A proposed revision of the Mental Health Act is considering the use of capacity as the key basis for detention, and the Government's proposals on mental incapacity have suggested the establishment of formal proxies for decision-making (Lord Chancellors Department, 1997).

Over two-thirds of responding consultants agree that the lack of safeguards is a problem. There is a risk, however, that if new processes were cumbersome, they might effectively obstruct the delivery of health care to the incapacitated. In our view the challenge now is to establish those safeguards in a way that is both effective as well as an efficient use of resources.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.