National training numbers (NTNs) in general adult and old age psychiatry appear to have increased significantly over the past 2 years. This is supported by the 17% increase identified by this survey. Senior house officer (SHO) posts feeding into this rise in national training numbers for specialist registrars have not increased. Within the Wessex Deanery, there are 35 national training numbers in general adult and old age psychiatry. Of the SHOs in Wessex who pass MRCPsych, 50% on average apply for specialist registrar training in the Wessex Deanery. Other trainees enter staff grade posts or flexible training, move abroad or go on to training schemes elsewhere in the country.

There has been a shortfall in local and external applicants to fill the increased number of national training numbers added to the scheme within the past 3 years. Prior to this increase, our local scheme was fully recruited through a competitive interview.

A nationwide snapshot survey was conducted to determine the current recruitment position on general adult and old age specialist registrar rotations in England, Scotland and Wales, so that it could be seen whether this was a local problem or was being replicated elsewhere.

Method

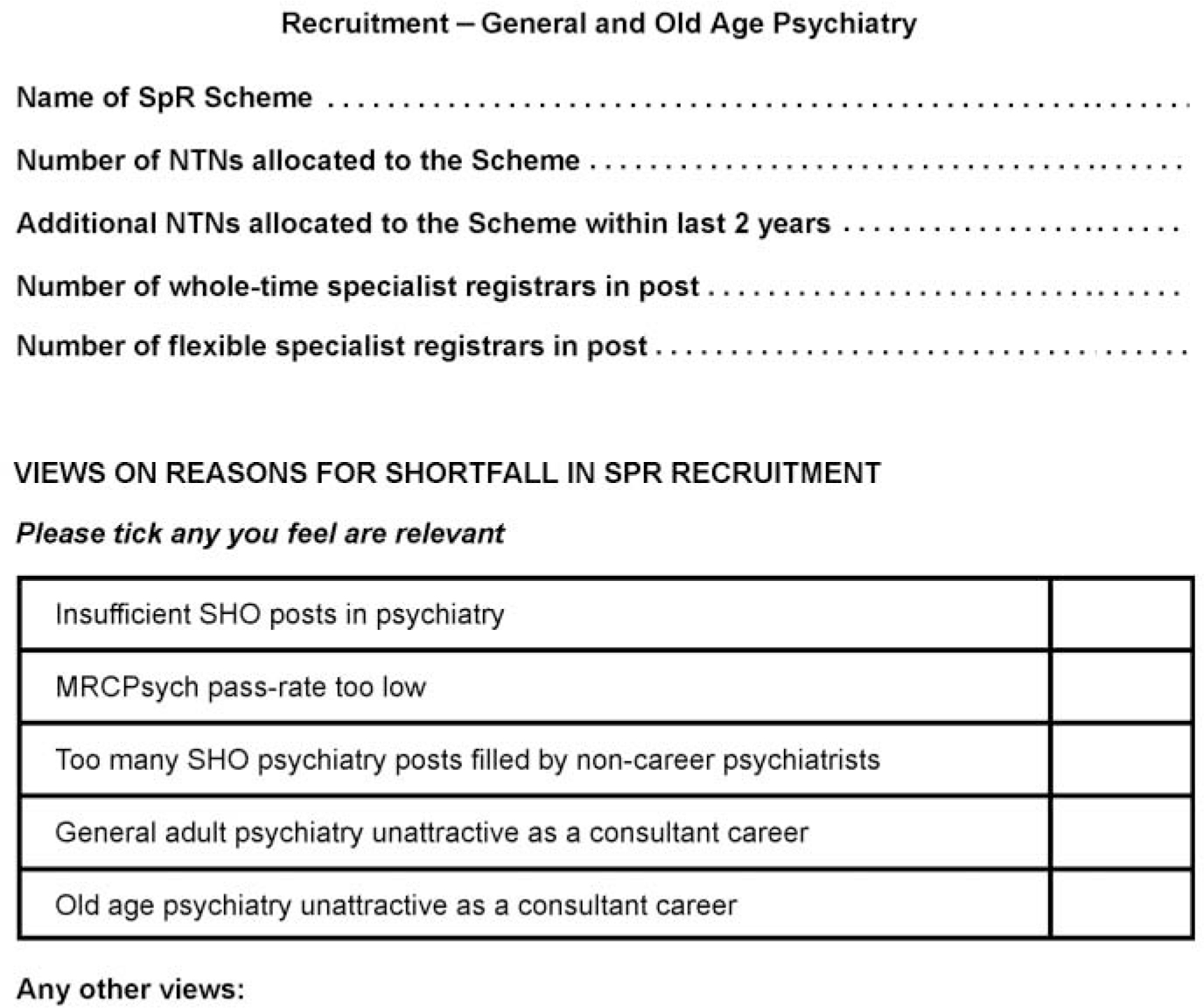

A questionnaire was designed (Fig. 1) and sent to all programme directors in England, Scotland and Wales for specialist registrar training schemes in general adult and old age psychiatry. The questionnaire addressed not only the issue of recruitment numbers to the specialist registrar training posts, but also the opinions of programme directors on the reasons for any identified shortfall.

Fig. 1. Format of postal questionnaire.

Results

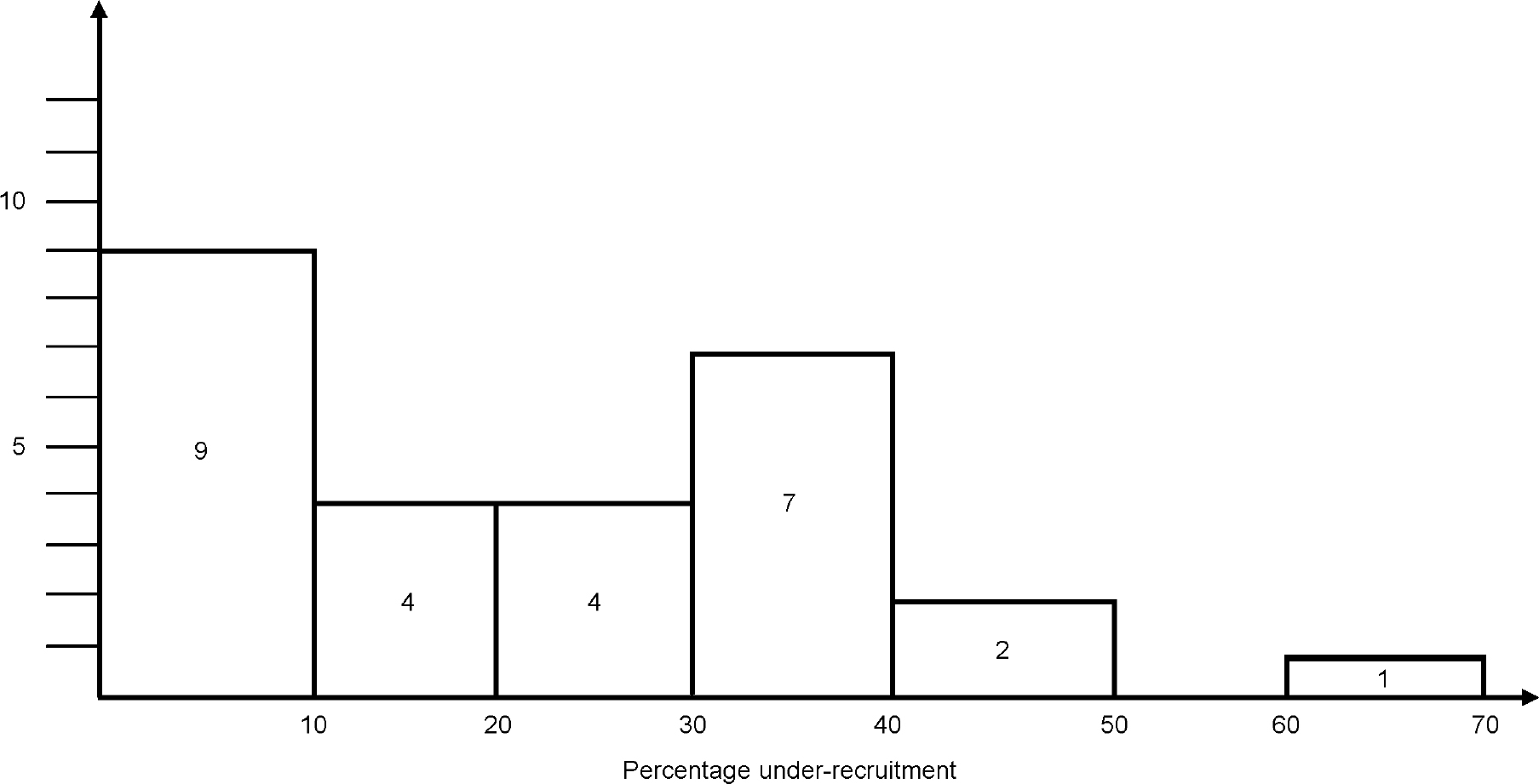

The response rate to the questionnaire was 27 out of 31 (87%). The four non-responding schemes were based on large conurbations, and were not obviously different from the urban schemes that did respond. Of the schemes surveyed, there was a total of 670 national training numbers and 158 of these were unfilled, giving a 24% vacancy rate for SpRs. The range for under-recruitment was 0% to 62%, the mean being 21%. The schemes with the highest recruitment were centred on large conurbations, with the lowest recruitment levels being identified in more rural areas. The distribution of the shortfall is graphically depicted in Fig. 2. In the schemes surveyed, there had been a 17% increase in national training numbers in general adult and old age psychiatry during the past 2 years.

Fig. 2. Under-recruitment within general adult and old age specialist registrar schemes.

The programme directors had the opportunity to give their views on the reasons for a shortfall in specialist registrar recruitment. These are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Identified reasons for under-recruitment at SpR level

| Statement | Agree (%) |

|---|---|

| Insufficient SHO posts in psychiatry | 42 |

| MRCPsych pass-rate too low | 7 |

| Too many SHO psychiatry posts filled by non-career psychiatrists | 30 |

| General adult psychiatry unattractive as a consultant career | 58 |

| Old age psychiatry unattractive as consultant career | 15 |

Programme directors from schemes identifying little problem in recruitment commented that: ‘Recruitment generally takes all applicants who are appointable in the past 4-5 years’; ‘We have about the same number of qualified applicants as we have posts available’; and ‘No shortfall; recent appointment committees over-subscribed’.

Comments from programme directors of schemes experiencing problems with recruitment included: ‘SHOs are taking career breaks or moving to staff grade jobs’; ‘Crisis looms in general psychiatry’; ‘Calibre of candidates for SpR posts fairly low’; and ‘General adult psychiatry very unattractive’.

Discussion

This survey is limited by the inherent bias of respondents answering a set questionnaire. The views expressed are those of programme directors, therefore further work looking at the views of trainees would add to the debate about recruitment in psychiatry.

Nationally, there appears to be a significant (24%) under-recruitment to specialist registrar training in general adult and old age psychiatry. The 17% increase in national training numbers in the past 2 years accounts for a large proportion of the 24% under-recruitment identified. As SpR numbers have increased, there has not been a corresponding increase in SHO numbers. An insufficient number of SHOs was identified by 42% of programme directors as a factor influencing under-recruitment. The limited nature of the survey prohibits further analysis. Adult psychiatry has been described as something done in training by all psychiatrists, prior to specialising in something else (Reference ColganColgan, 2002). These results certainly support the view that adult and old age psychiatry are not attracting sufficient SHOs into higher training, although these SHOs have all had experience in these areas prior to passing the MRCPsych. The increase in national training numbers for general adult and old age psychiatry in the past 2 years does not appear to have been matched by an increase in the number of applicants for the posts. Reasons for this have been stated as: inadequate resources, public expectations, manpower and quality of training (Reference Wilson, Corby and AtkinsWilson et al, 2000). A planned additional increase in national training numbers without a corresponding increase in SHO posts can only lead to a further crisis in recruitment at specialist registrar level, unless steps are taken to address some of these issues. Schemes that are currently running at a healthy 90%-plus level of recruitment (nine out of 27 surveyed) are likely, with a further increase in national training numbers, to continue recruiting well and this could lead to a further decline in the recruitment to other schemes. In turn, this could lead to an imbalance in the distribution of specialist registrars in training and consequently a further crisis in recruitment at consultant level in these same areas of the country. Filling consultant posts is already difficult, with 14% of consultant vacancies overall being identified in the Royal College of Psychiatrist's 1998 Census (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1999). Reasons contributing to this include early retirement and haemorrhage into the private sector (Reference Kendell and PearceKendell & Pearce, 1997).

The issue of the unattractiveness of general adult psychiatry as a consultant career has been highlighted by the programme directors who responded to the survey. The unlimited responsibility of general adult psychiatrists appears to be unique to this country and undoubtedly contributes to its unattractiveness (Reference BristowBristow, 2001). This issue cannot be addressed by individual training schemes in an attempt to recruit people into higher training in general adult and old age psychiatry.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.