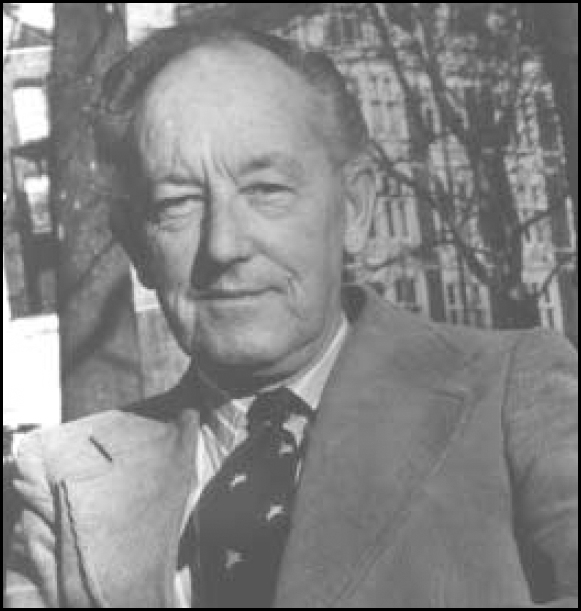

David Stafford-Clark, who died aged 83, was in his day, one of the foremost psychiatrists in the country. He was Physician-in-Charge of the Department of Psychological Medicine and Director of the York Clinic at Guy's, as well as Consultant at the Institute of Psychiatry, University of London. But this summary sells him short: David brought to psychiatry a lively intelligence, humour, a lack of pomposity, but above all, an exemplary compassion and concern for the individual. His contribution to clinical psychiatry contrasted with the therapeutic inertia and detachment that pervaded psychiatry at the time. He was also a gifted teacher. His clinical lectures at Guy's were always packed to the doors by students who regarded most lectures as risible.

He qualified in medicine in 1939 at Guy's. He had been advised to study medicine there by the family doctor, after leaving Felsted - and that was that. He remained loyal to Guy's for life.

During the war he served as a doctor in the RAF, attaining the rank of Squadron Leader. His wartime career included being one of the last members of the British Expeditionary Force to leave France, in a collier, one jump ahead of the Wehrmacht. He returned to Bomber Command, where his work on morale in air crews stimulated an interest in psychiatry which had started in his student days, when he was appalled by seeing mental hospital patients paraded in front of medical students like freaks in a circus in the name of ‘teaching’. In addition, he became a medical parachutist. He volunteered and flew as a doctor, was mentioned twice in dispatches, and inhaled poison gases at Porton Down. The legacy from this was asthma, from which he suffered for the rest of his life, culminating in a near fatal attack which led to early retirement on health grounds, at the summit of his career.

He had returned to Guy's after the war, and later started his postgraduate training in psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry, where he caught the eye of Sir Aubrey Lewis. After a spell as a teaching Fellow at Harvard and the Massachusetts General Hospital, he returned to the Maudsley as Chief Assistant to the Professorial Unit. During this period he carried out electro-encephalogram studies on alleged murderers on remand; work which high-lighted the unrecognised incidence of psychiatric disorder and epilepsy in those potentially facing the death sentence by hanging. A career in forensic psychiatry was aborted by his becoming the Director of the York Clinic at Guy's. Sir Aubrey Lewis had long since spotted that David was a populist, and he recommended him to Sir Allen Lane of Penguin, as being someone best qualified to write Psychiatry Today, the highly successful book which was translated into 12 languages.

David's ability to communicate and clarify the supposed arcana of psychiatry was masterly, and he inspired enthusiasm for the speciality among students and doctors deterred by its obscure terminology and vagueness. His interest and influence were founded on simple clinical principles. For David, psychiatry was a speciality never to be divorced from medicine. It should be practised in the general hospital away from the isolation of the mental hospital: when psychiatry left medicine, it ceased to be psychiatry. Proper history-taking and examination and assessment of the person's mental status were summarised in a clinical formulation aimed at dealing with and relieving the patient's distress. David encouraged students to develop a proper concern for the relief of human suffering. These concerns took precedence over lofty generalisation and speculation about the relevance of social and obscure psychological factors. Regard for, and empathy with, the individual and their problem and how that person is feeling, was, for David, where psychiatry must start and end. He was against the prevailing teaching hospital ethos of tweedy philistinism in which psychiatry was regarded with poorly disguised contempt. David did much to dispel this in a positive fashion, by encouraging the practice of a medically-based discipline founded on compassionate understanding and respect for the patient. His ability to communicate this philosophy of medicine and psychiatry found expression in radio and television, in particular in the television series Lifeline, which ran from 1957 to 1963. It was a pioneering endeavour in the communication of the problems of psychiatric and allied disorders, and set an example at a time when public presentations were regarded as revolutionary, if not dangerous, by the more conservative members of the profession. The ensuing popular appeal incurred him ill-feeling and envy among certain members of the medical establishment. But David could handle criticisms of his public appearances, his exuberant personality, and his espousal of controversial causes. David's concerns spread into areas which counted for little among those anti-intellectual colleagues who found some of his opinions not to their liking. He had better things to do than worry over such trivia. He was always fun to be with.

In the York Clinic, he promoted an atmosphere in which everyone felt enthusiastic; a feeling that spread throughout the staff, producing a community atmosphere that will be long remembered. He leaves a widow, Dorothy, whom he married in 1941, a daughter and three sons, one, Max, the renowned theatre director.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.