The Drug Treatment Centre Board in Dublin runs the largest substance misuse treatment centre in Ireland, with over 500 clients from all over Dublin registered with the clinic. The vast majority are on substitution treatment for opiate dependence. However, cocaine use is increasingly becoming a major problem in this group as the use of the drug in the country continues to increase. In January 2008, a report by the National Advisory Committee on Drugs, and the Drug and Alcohol Information and Research Unit noted a significant increase in lifetime cocaine prevalence rates among all adults (15-64 years of age) in Ireland, from 2.5% in 2002/2003 to 5.1% 2006/2007 (National Advisory Committee on Drugs, 2008). In a national multi-site evaluation in the USA (Reference Hubbard, Craddock and FlynnHubbard et al, 1997), cocaine misuse was found in 42% of those beginning treatment with methadone and in 22% of the same group at 1-year follow-up. Cocaine misuse during opioid maintenance treatment has been associated with poor treatment outcome (Reference Demaria, Sterling and WeinsteinDeMaria et al, 2000); a high risk of HIV infection (Reference Bux, Lamb and IguchiBux et al, 1995); higher levels of family, medical, vocational and legal problems; and continued focus on drug-related criminal activity (Reference Kosten, Rounsaville and KleberKosten et al, 1987). Clients with cocaine dependence also have a greater risk of suicidal behaviour (Reference Marzuk, Tardiff and LeonMarzuk et al, 1982).

The aim of the study was to quantify the number of regular users of cocaine in the treatment centre, using a cut-off point of half weekly urine samples testing cocaine positive in a 12-week period. The study also sought to find out what proportion of this cohort of regular users fulfil dependence criteria as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) (Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 2002).

Method

Participants

Using the database from the clinic laboratory, information was obtained about urine drug test results for all clients attending the drug treatment centre over a 12-week period between 7 August and 30 October 2007 (clients are required to submit a urine sample for drug analysis once a week as part of the treatment programme). The results were then analysed to find the number of clients whose urine samples tested positive for cocaine in more that 50% of cases. Only those who provided more than four samples over the period of analysis and had provided a sample within 3 weeks of the commencement date of the study were selected for further assessment. All eligible candidates provided written voluntary consent for involvement in the study. The study and all its procedures were approved by the drug treatment centre board ethics committee.

Diagnostic measures

Participants fulfilling the study criteria were assessed for cocaine dependence using SCID-I. The assessment was carried out by a psychiatrist.

Results

Participants

The data from the laboratory showed that 419 clients had submitted a minimum of four urine samples for drug testing in the 12-week period, of which 38 (9.1%) met the inclusion criteria of at least half for cocaine positive samples in this period.

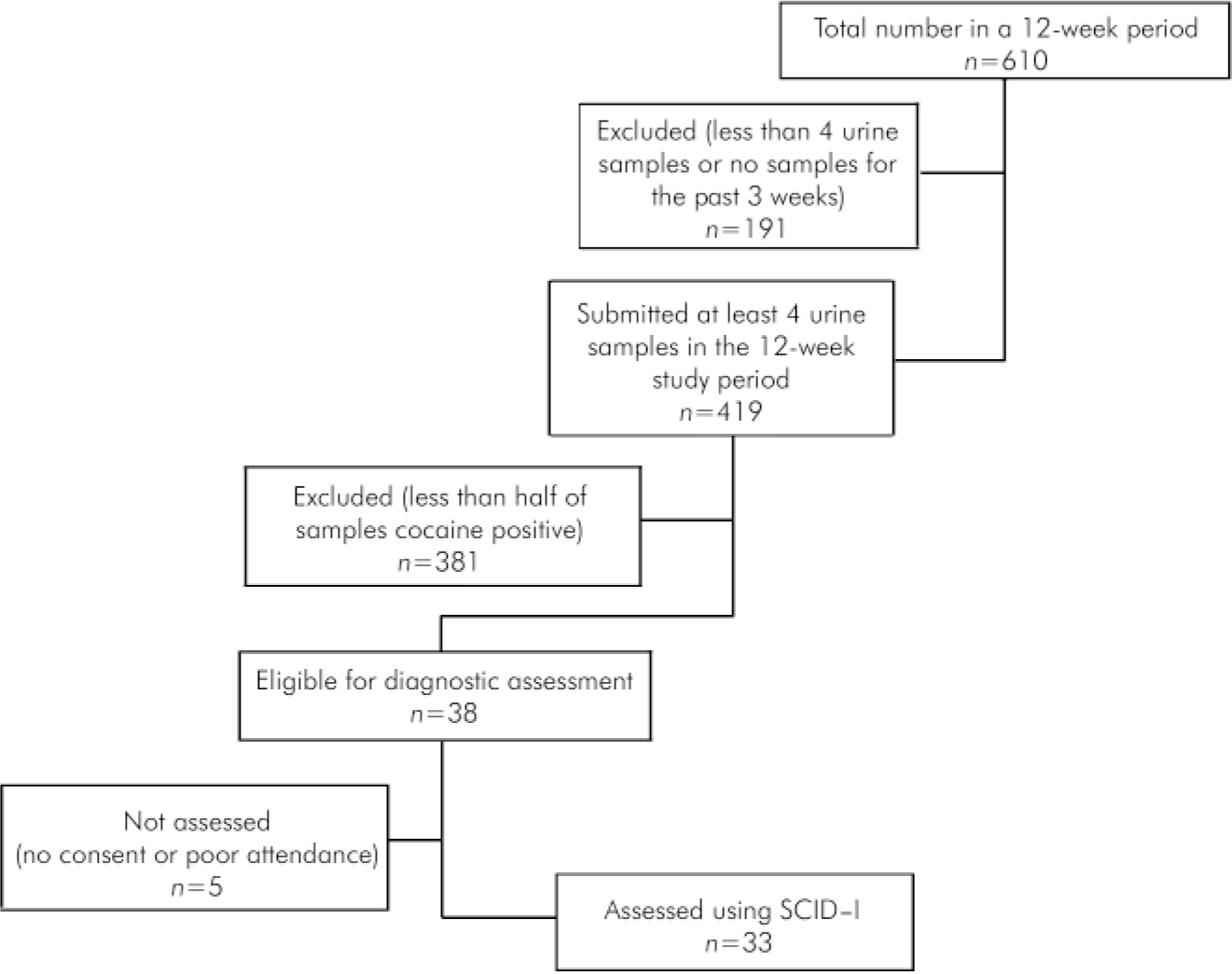

Of the 38 candidates who were eligible for assessment for cocaine dependence, 2 did not give their consent to participate in the assessment (5.3%) and 3 (7.9 %) could not be assessed for other reasons (1 was in prison, 1 had since stopped attending the clinic and 1 had a very poor attendance record). Therefore, 33 of the eligible candidates were assessed for cocaine dependence. The flow of candidates through the study up to the assessment stage is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Study profile.

Outcomes

Of the candidates who were assessed using SCID-I, 32 satisfied the criteria for cocaine dependence and 1 did not (Table 1). Therefore, 84.2% of all eligible candidates satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for dependence and 2.6% did not. Of the 32 candidates who satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for dependence, 3 (9%) did not meet the criteria in the last month before the diagnostic assessment; 25 (86%) of those who met the criteria for cocaine dependence in the previous month had physiological dependence to the drug.

Table 1. Results of the SCID–I assessment

| Gender | Current cocaine dependence, n | Cocaine dependence, but not in month before assessment, n | No cocaine dependence, n | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 21 | 3 | 1 | 25 |

| Female | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 29 | 3 | 1 | 33 |

Discussion

The study aimed to assess the extent of cocaine dependence among clients attending treatment for opiate addiction. The results showed that 9.1% of clients attending an opioid dependence treatment clinic were regular users of cocaine and 84.2% of these satisfied the DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence as assessed by SCID-I. In total, 7.7% of clients attending the clinic had cocaine dependence. This compares well with previous studies of cocaine dependence in this population group, where 9% of daily cocaine misuse was found in patients 6 months after admission into methadone maintenance treatment, falling to 6% after 12 months (Reference Dobler-Mikola, Hättenschwiller and MeiliDobler-Mikola et al, 2005). Although most available data tend to quote cocaine use and cocaine misuse, this study set out to find the rates of cocaine dependence in a chosen population group.

The 2007 report from the National Advisory Committee on Drugs in Ireland noted that treatment programmes in Ireland are not designed for stimulant users and that opiate-based treatment services have to deal with increasing numbers of individuals presenting with cocaine-related problems (National Advisory Committee on Drugs, 2007). Cocaine use is higher among individuals with opiate dependence in maintenance treatment than among the general population (Reference Haasen, Prinzleve and ZurholdHaasen et al, 2004). Although effective substitution pharmacological treatment is available for opioid dependence, there is no similarly effective intervention for primary cocaine dependence (Reference Delima, Deoliviera Soares and Reisserde Lima et al, 2002). However, psychosocial interventions, mainly contingency management and cognitive-behavioural approaches, have been effective in the management of cocaine addiction (Reference Rawson, Huber and McCannRawson et al, 2002).

Drug treatment programmes focusing mainly on opiate addiction need to adapt so that they can deal with increasing numbers of cocaine users (National Advisory Committee on Drugs, 2007). This will require resources and training in non-pharmacological approaches that have been shown to be effective in treating cocaine addiction.

Limitations

The sample of those who were eligible for assessment was quite small. Of the 38 clients eligible for diagnostic assessment, 5 (13%) could not be assessed, which could have affected the outcome. At any given time, patients who fail to stabilise on opioid agonist maintenance are placed on a low-dose regime for a defined period of time as part of contingency management and do not have to provide urine samples. Therefore, they would not be included in this study. This group tend to be more likely to be misusing cocaine as well as opiates. Excluding this group could have underestimated the prevalence of cocaine dependence in the clinic.

Diagnostic assessment was carried out by one individual which could have resulted in bias.

Despite the limitations of the study, the results show that there is a significant cocaine dependence problem among clients attending opioid treatment centres. Appropriate services need to be put in place to address this.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

I thank the clients at the Drug Treatment Centre, Dublin, who took part in the study and Dr Brion Sweeny for his guidance.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.