Reforms to address perceived deficiencies in American elections have included changes to primary rules (Grose Reference Grose2020; McGhee et al. Reference McGhee, Masket, Shor, Rogers and McCarty2014), redistricting reform (Grofman and Cervas Reference Grofman and Cervas2018; Nagle Reference Nagle2019; Saxon Reference Saxon2020), and revisions to election registration and balloting rules (Burden et al. Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2014), among others (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cervas, Grofman and Lipsitz2021). One particular voting reform that has generated significant recent interest is the instant runoff election, commonly referred to as ranked-choice voting (RCV).Footnote 1 This electoral reform was recently implemented in Maine and was adopted in Alaska for federal elections beginning in 2022.Footnote 2 It also is being used in various cities, including city council elections in San Francisco and the New York City mayoral race. RCV is purported to have several positive characteristics, including reduction in negative campaigning and a greater likelihood of electing moderate candidates. It almost certainly leads to the encouragement of more candidates, including women and racial minorities (John, Smith, and Zack Reference John, Smith and Zack2018). One indisputable advantage of RCV is the ability it gives a voter to support a candidate with a lesser chance of winning while still providing support for a candidate with a higher probability of victory by including both in the voter’s ranking.

In the United States, the most ardent supporters of RCV tend to be liberal reformers, who call to mind examples of situations in which RCV would have benefited Democrats. Because this reform is being pushed by the political left, it is seen—incorrectly—as being biased against Republicans; RCV’s opponents tend to be Republicans. For example, an unsuccessful lawsuit in Maine brought by members of the Republican Party asked the court to find RCV unconstitutional (United States District Court District of Maine 2018).

This article provides evidence of why, in contemporary presidential politics, RCV should be attractive to Republicans. However, the bottom line is simple: a priori, there is no reason to believe that RCV has any partisan or ideological bias, even if it might be shown to favor (relative to a simple plurality) one party or another in particular circumstances.Footnote 3

…the bottom line is simple: a priori, there is no reason to believe that RCV has any partisan or ideological bias, even if it might be shown to favor (relative to a simple plurality) one party or another in particular circumstances.

The role of minor-party candidates as potential “spoilers” has long been a topic of concern. That concern became more salient after Ralph Nader’s role in denying Al Gore the 2000 victory in Florida, thereby denying him the presidency. As a consequence of Nader’s taking votes from the Democratic candidate, much of the subsequent outcry has been about Green Party candidates costing Democrats votes. In 2016, there were assertions that Jill Stein, the 2016 Green Party candidate, was a spoiler for Hillary Clinton (see Herron and Lewis Reference Herron and Lewis2007; Magee Reference Magee2003; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2016; and the following discussion). However, even if minor-party candidates did not change the presidential election outcome in 2016 (Devine and Kopko Reference Devine and Kopko2016, Reference Devine and Kopko2021), can we state the same for 2020? Unlike the election in 2016, the 2020 election did not exhibit an Electoral College inversion of the popular vote (Cervas and Grofman Reference Cervas and Grofman2019). Nonetheless, despite Joe Biden having won the national popular vote by more than seven million votes, the outcome was very close in many states—as it was in 2016—including the pivotal states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Indeed, with only a few thousand changes in votes, Trump would have been reelected in 2020. Moreover, as we demonstrate, there was an even greater scope for minor-party candidates to have affected the election outcome in 2020 than was the case in 2016.

After reviewing work on the effects of minor-party candidates in 2016 and then examining the probable effects of minority-party candidacies in 2020 under current election rules, we consider what might have happened in 2020 had presidential voting taken place under RCV. On the one hand, this reform generally is touted in terms of its impact in promoting minor parties by allowing voters to cast votes for the candidates of minor parties without harming the chances of major-party candidates who would be a voter’s second choice. On the other hand, RCV also can be thought of as an “anti-spoiler” reform that reduces the likely impact of minor-party candidates on election outcomes. Thus, we have a pro-RCV coalition in which minor-party supporters tend to favor this reform because it presents a way to affect the two-party cartel that has dominated American politics for the past 150+ years together with major-party supporters who believe that RCV, in general, will help moderates—an advocacy especially true for Democrats concerned about spoiler votes from the left.Footnote 4

Democrat support for RCV was reinforced when the Democratic candidate, Jared Golden, defeated Republican incumbent Bruce Poliquin, after multiple rounds when all candidates failed to reach 50% of the vote in the first round for the 2018 Maine second congressional district. Poliquin received more first-place votes than Golden, and his failure to secure the seat infuriated him, who called the outcome the “biggest voter rip-off in Maine history” (Maine Examiner 2019). Poliquin then unsuccessfully sued the secretary of state, claiming he won the “‘constitutional’ one-person, one-vote first-choice election” (Pathé Reference Pathé2018).

Whereas we agree with Wolfinger’s famous observation (quoted in Wuffle Reference Wuffle1986) that “data is the plural of anecdote,” it also is important to remember another aphorism—namely, “not all swans are white.” Concluding that RCV necessarily (or even usually) can be expected to benefit Democrats is simply wrong. Based on the two most recent presidential elections and building on Devine and Kopko (Reference Devine and Kopko2021), we show that at the presidential level, RCV actually is likely to benefit the Republican nominee.

THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 2016

In 2016, there were two minor-party candidates who received at least a million votes: Gary Johnson, running as a Libertarian, won 4.5 million votes, and Jill Stein, running as the Green Party candidate, won 1.5 million votes.Footnote 5 It is common to view Libertarians as ideologically closer to Republicans, in part because some high-profile Libertarians are former Republicans (e.g., Gary Johnson was the Republican governor of New Mexico before being the Libertarian presidential candidate in 2012 and 2016), whereas Green Party candidates are perceived as ideologically closer to Democrats because they tend to have platforms uniformly to the political left of the Democrats.Footnote 6

In 2016, if Johnson’s voters had instead all chosen Trump and Stein’s had all chosen Clinton, Trump would have lost the popular vote by only 220,461 votes rather than the actual 2,868,686 votes. Moreover, under this strong assumption, the outcomes would have changed in four states: Trump would have won additional electors in Maine and won Minnesota, Nevada, and New Hampshire, for an additional 22 Electoral College votes. In contrast, under these assumptions, there are no additional Clinton victories. Thus, under the assumptions most favorable to minority-party impact, the absence of minority-party candidates would have significantly benefited Trump in terms of both popular vote and Electoral College seat share—but still would not have changed the outcome. However, if only Stein did not run but Johnson remained, Clinton likely would have picked up electors in at least one state: Michigan (Devine and Kopko Reference Devine and Kopko2021).

Nevertheless, it is unrealistic to assume that all minor-party supporters would have shifted their support to a major-party candidate if their preferred choice were not in the contest. Supporters of minor parties can exhibit negative affect toward both major parties (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018), leading to abstention. Using a multinomial probit model and building on Lacy and Burden’s (Reference Lacy and Burden1999) analysis of the 1992 presidential election, Devine and Kopko (Reference Devine and Kopko2021) estimated that about half of the minority-party supporters would not have voted if their own candidate had not been in the race. They also estimated that in 2016, among non-abstainers, about 60% of the voters who ranked the Libertarian candidate, Gary Johnson, first would have ranked Trump second and about 32% to 33% would have ranked Clinton second. Similarly in 2016, they estimated that about 75% to 80% of voters who ranked the Green Party candidate Jill Stein first would have ranked Clinton second and about 20% would have ranked Trump second. We conclude that, on balance—at least vis-à-vis the popular vote—minor-party candidates in 2016 hurt Trump more than they hurt Clinton.

THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 2020

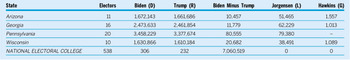

In 2020, there was again a Green Party candidate for president, Howie Hawkins, and again a Libertarian candidate, Jo Jorgensen. However, in 2020, Green Party supporters were more anxious to defeat Trump. They recognized Trump’s victory as a real possibility and thus were more likely to choose to vote strategically. Hawkins failed to make the ballot in 22 states, whereas Stein was on the ballot in all but three states in 2016. Thus, the votes for the Green Party candidate were significantly fewer in 2020 than in 2016 (i.e., 405,035 versus 1,457,288).Footnote 7 In contrast, Jorgensen performed substantially better in terms of raw votes, with 1,865,724 votes in 2020—although still far from the 4.5 million votes for Johnson in 2016. Distribution matters! The 2020 data for four key states are shown in table 1.

Table 1 2020 Election Results in Four Pivotal States

The table shows that Jorgensen’s votes, in principle, could have affected the outcome in three states (i.e., Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin), with a combined total of 37 electors. In these states, the margin of Biden’s victory was not only less than the Jorgensen vote share but also less than the Jorgensen vote share minus the vote share of Hawkins—sometimes markedly so. These are the only three states won by Biden in which the Jorgensen vote relative to Biden’s vote margin is significant enough to plausibly affect the outcome.Footnote 8 The 37 Electoral College votes in these three states would have been enough to change the Electoral College outcome to a tie if all three states had gone to Trump. If there had been a tie in the Electoral College, voting would have gone to Congress; with each state’s delegation in the House voting as a bloc and with votes in tied state delegations not counted, Trump would have won because Republicans control more delegations in more states. We note that because of this state-based bloc-voting rule, the party that holds the majority in the House nevertheless could fail to elect its preferred presidential candidate (Foley Reference Foley2020).

Also noteworthy is the potential importance of minor-party votes in Pennsylvania. If every Jorgensen voter in that state had switched to Trump, the state outcome would have been very close, with a gap of only 1,175 votes. During the certification of votes, Pennsylvania was one of the states asserted by Republicans to have irregularities, and its outcome continues to be challenged by former President Trump (as of September 2021). In light of the events of January 6, 2021, we can only imagine the furor if the outcome of the election in Pennsylvania had been this close.

Of course, positing that all of the Hawkins votes would go to Biden and that all of the Jorgensen votes would go to Trump is highly unrealistic. Nevertheless, whereas only voters know for sure how they would vote if certain candidates had not been on the ballot, plausible inferences are possible. What is likely to have happened if Jorgensen (or perhaps both Jorgensen and Hawkins) had not been on the ballot in 2020 and there was no other Libertarian candidate to replace Jorgensen?

Imagine that Hawkins remains in the race in 2020 but there is no Libertarian candidate. If we posit that the same second-preference rankings found by Devine and Kopko (Reference Devine and Kopko2021) for 2016 apply to Libertarian voters in 2020, and we posit that half of the Libertarian voters would have abstained if their candidate had not been in the race in 2020, we now would find that no states shift in 2020.Footnote 9 Conversely, if we posit a zero rate of abstention for former Jorgensen voters, then there are two states that shift to Trump: Arizona and Georgia—and these two states would shift to Trump even if all of their Hawkins voters shifted to Biden. However, these two states still would not be enough to change the Electoral College outcome.Footnote 10

We might think that these results indicate that minority-party candidates did not have any real impact in 2020, but this is much too strong a conclusion. Assuming a 50% abstention rate if there were no Libertarian option on the ballot, Trump would have gained almost 260,000 net votes. Moreover, if there had been no Libertarian candidates on the ballot but all Libertarian voters still participated, with Trump receiving 60% of their votes, Arizona and Georgia would have flipped in 2020. Trump’s popular-vote loss also would have shrunk by 522,403 votes—and, importantly, Pennsylvania would have been considerably closer.Footnote 11

RANKED-CHOICE VOTING

Let us ask a different but related question about the 2020 presidential election. What might have happened in 2020 had RCV been used instead of plurality? RCV asks voters to rank the candidates. Under Maine rules for RCV for federal elections (Akula, Cervas, and Goren Reference Akula, Cervas and Goren2020), if no candidate receives a majority of first-choice votes, then the candidate with fewest first-choice votes would have the votes on the ballots that ranked that candidate first reallocated to the voter’s second choice on the ballot. The process continues in this way until one candidate has a majority of the then-valid first-place votes. If it has not already been decided by one candidate receiving a majority of the votes in an earlier round, this process must eventually lead to a two-candidate contest and thus a clear winner. RCV makes it easier for voters to express their true preferences without being concerned about whether their vote will be wasted on a candidate who has no real chance of winning; therefore, we might think that RCV would encourage turnout by minority-party voters. Of course, the counterfactual evaluation of any rule-change effect requires a note of caution. It would not only be changes in turnout levels affected by a shift to RCV; the consequences of a change in electoral rules include different incentives for candidate entry, strategic voting in the mass electorate, and different campaign strategies. For instance, a Trump candidacy might have been less (or more) likely in 2016 if RCV had been in place for the Republican primary. The set of competitors might have been different and the outcome very well may have been affected. Under a different voting rule, calculations about whether to enter the race would have changed. Some of Trump’s rivals in 2016 might have defeated him in head-to-head competition at the end of an RCV process, or there might have been more incentives for candidates to seek support from their rivals that would have changed who was eliminated when.Footnote 12 In 2020, because the two major parties received the majority of the votes cast, it would have been the voters who had selected a minor-party candidate as their first choice who would have their second (or third) choice counted in the final round. Is it plausible to assume that the Jorgensen vote would have gone disproportionately to Trump under RCV? The answer is yes—at least using the 2016 estimates of Libertarian voting behavior from Devine and Kopko (Reference Devine and Kopko2021) as our guide.

What might have happened in 2020 had RCV been used instead of plurality?

Let us assume that the same set of voters vote in our hypothetical 2020 RCV election—that is, there are no abstentions because their preferred candidates are on the ballot. We further assume that minor-party supporters vote in the manner posited by Devine and Kopko (Reference Devine and Kopko2021), with those who do vote providing a ranking to at least their top two candidates. Of course, these are strong assumptions, but two states would flip to Trump under RCV even if as many as 50% of the minor-party candidate voters “undervote.”Footnote 13 Although the use of RCV rather than plurality could be expected to have changed the nature of the campaigning and thus the ultimate vote distribution, it still is not unreasonable to believe that had the 2020 election been held under RCV, Trump would have captured two states that in fact he lost and come within 11 votes of an Electoral College victory. Therefore, based on this analysis and in looking forward to a potential 2024 third presidential campaign, Trump should be seriously concerned about a Libertarian spoiler. Given this distinct possibility, he should be a strong supporter of RCV being used in 2024 because it will mitigate the spoiler effect—and the same is potentially true for any Republican presidential candidate in 2024.

Opposition to RCV from the political right is rooted in the idea that liberals would benefit from such a reform, especially in general elections. However, whether any given minor-party candidate will take votes from major-party candidates in a way that benefits the Democrats as opposed to the Republicans depends on the nature of the candidate and the particular circumstances at the time. The appeal of RCV should not depend on expectation of partisan gain because, in the long run, RCV is neutral.Footnote 14 As noted previously, RCV largely eliminates the problem of spoilers while still encouraging the participation of minority-party voters.

The appeal of RCV should not depend on expectation of partisan gain because, in the long run, RCV is neutral.

Nevertheless, it is useful to remember that no reform comes without unintended consequences. This article demonstrates that it was Trump who was more likely to have been harmed by third-party candidates in 2016—and especially in 2020—than his Democratic opponent. It would be ironic, indeed, if a reform supported by liberals and adopted in cities such as San Francisco and New York for local elections resulted in a Trump restoration if it were used to elect a president in 2024.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Elsie Goren and Anjali Akula for excellent research assistance. We also thank Christopher Devine and Kyle Kopko for sharing an early draft of their paper. We have benefited greatly from the comments of the two editors and the three reviewers who, in addition to helping improve the article, saved us embarrassment by alerting us to unforgiveable errors in our numbers. We extend further gratitude to the copyeditor for improving this manuscript. Grofman’s involvement was supported by the Jack W. Peltason Chair at the University of California, Irvine.