We are humbled by the quantity and quality of the commentaries on our article in this special issue. Our goal was not to answer definitively how global democracy has changed in recent years but rather to provoke a debate about how we collectively can improve the scholarship on this question. The range of viewpoints raised in this special issue have made important advances on this goal.

Rather than providing a comprehensive response to individual contributions, we use this reply to highlight what we view as the key points of consensus arising from the articles in this special issue, points of disagreement, and paths forward for future research.

WHAT TO EXPLAIN AND WHY IT MATTERS

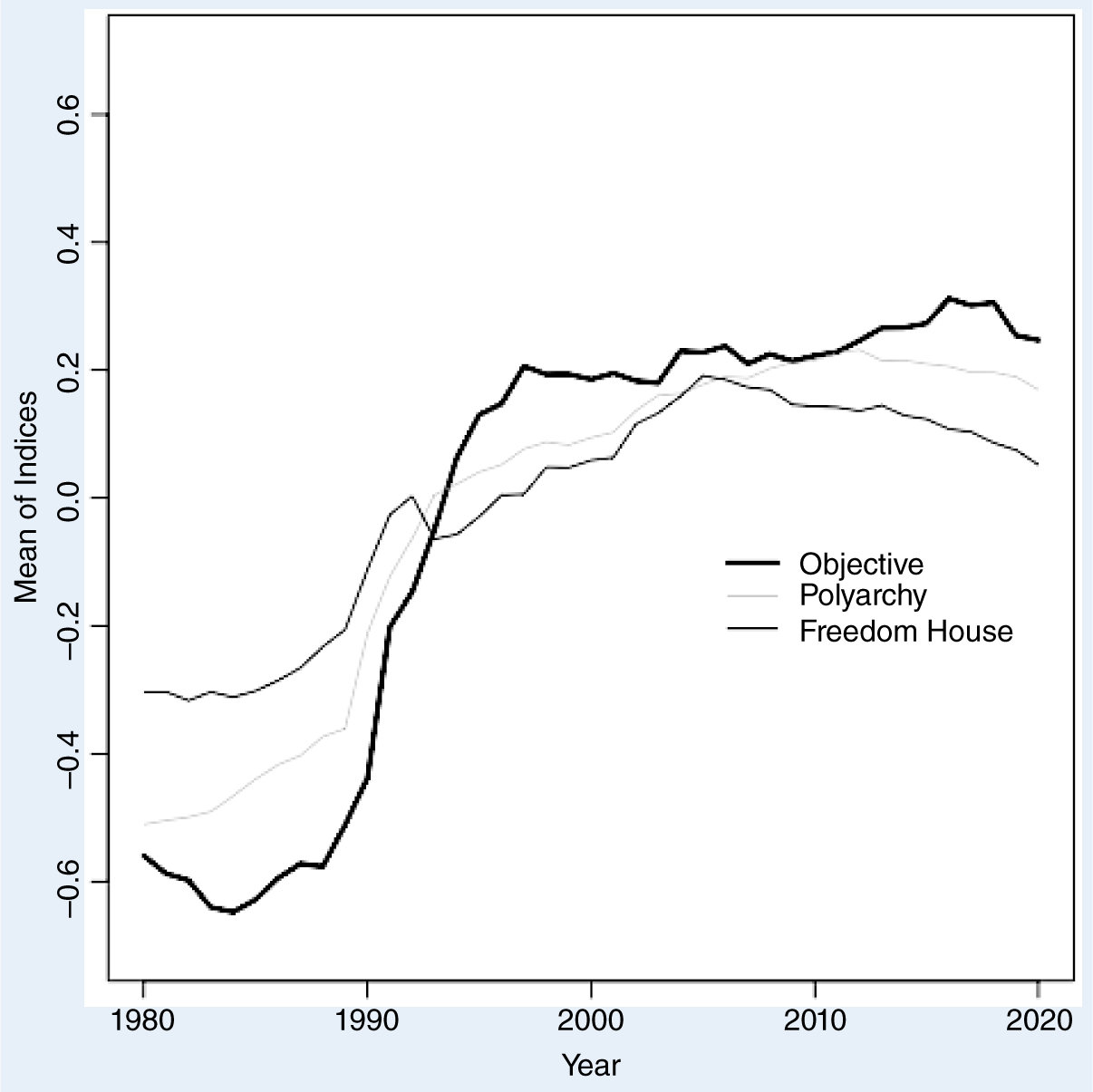

To begin, it is worth reminding ourselves what different aggregate measures of democracies say about the trends in recent decades. Figure 1 plots the average of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Polyarchy score (thin gray line), the Freedom House democracy score (thin black line), and our objective index (thick black line). To facilitate comparison of trends, all three are normalized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 during this time frame.

Figure 1 Averages of Democracy Indices Over Time

The differences in trends are not especially dramatic. For V-Dem and Freedom House, there is a modest decline in recent years; by our objective index, the scores are mostly flat with an even smaller decline in the final years. Weitzel et al. (Reference Weitzel, Gerring, Pemstein and Skaaning2023) find an almost identical trend as in our index using a more sophisticated technique to create democracy scores on a country-year level and using a different set of objective data. Given these minor differences, we understandably could ask why the articles in this special issue seem to describe different realities and whether these minor differences even warrant a special issue.

One reason to continue reading is that for a topic as important as global levels of democracy, minor differences even in a few countries can translate to consequential differences in the lives of billions of people. Furthermore, by delving more deeply into what drives these differences, we see that there is still much to learn about the nature of recent democratic change, what scholars can do to sharpen this understanding, how activists can improve the situation, and what we might expect in the future.

Our central empirical claim is that measures of electoral competition—universally accepted as a key component of democracy—and many other objective metrics have not declined during the past decade (Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2023). None of the responses disputes this finding.

Our central empirical claim is that measures of electoral competition—universally accepted as a key component of democracy—and many other objective metrics have not declined during the past decade. None of the responses disputes this finding.

Rather than challenging the empirical facts that we document, the most strident critiques instead point out that our article does not accomplish goals that we did not set out to achieve. First, we do not attempt to create a complete and reliable new democracy indicator to be used on a country-year level (Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023) or one that can predict democratic breakdown (Miller Reference Miller2023). We reiterate the warning from our initial article: our summary objective index is not a democracy score, and scholars should not use it as such (Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2023). This misuse will lead to nonsensical results and risk blurring rather than improving the debate.Footnote 1

Second, by focusing on aggregate trends, we do not attempt to argue that any individual cases are miscoded (Miller Reference Miller2023) or that concerns about backsliding in any prominent case are misplaced.Footnote 2 As we state in our article, there are approximately 200 countries in the world, and backsliding most likely is occurring in some countries at any given time.Footnote 3 Although case studies that identify instances of backsliding are important for other purposes, they do not systematically reflect broader global trends, which is the emphasis of our article.

Third, because we focus on examining objective variables that are based on factual coding, we do not provide any direct tests for coder bias in expert-coded data. However, we find it useful that some of the commentaries attempt to do so (Bergeron-Boutin et al. Reference Bergeron-Boutin, Carey, Helmke and Rau2023; Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023).

Several articles emphasize another important fact: different trends emerge when using a more expansive definition of democracy, relying on expert-coded data, or weighting by population (e.g., Gorokhovskaia Reference Gorokhovskaia2023; Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023). Our disagreements primarily are concerned about what drives these differences. One possibility is that the decline in subjective measures is driven largely by changes in the information environment and coding standards. Another possibility is that objective measures miss important components of backsliding. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and there may be some truth to both. They also are not mutually exhaustive; future work may propose other explanations that make more sense of recent trends in global democracy.

In summary, there is considerable consensus in this special issue about the general facts to be explained and the importance of studying the topic. We all agree that democratic backsliding and breakdown are occurring in at least some countries; understanding where and why this happens deserves considerable scholarly attention.

The commentaries on our article are full of promising ideas about how to accomplish these goals. More generally, they provide various approaches to improve the measurement of backsliding, as well as more substantive directions for future research (e.g., what explains variance in resilience to backsliding and how individuals perceive changes in democracy).

ONGOING DEBATES

This section outlines four major debates that emerged in this special issue (Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023 has a similar list). First, what is the appropriate sample of cases for examining backsliding? Second, should we use a thick or a thin definition of democracy? Third, how should backsliding be measured? Fourth, what is the appropriate standard of evidence to use for claims about backsliding?

These disagreements cause us to interpret the empirical patterns in a different manner. All of these contrasting viewpoints have merit and tradeoffs. Public-facing scholarship gives the impression that political scientists have reached consensus that we are in a period of major democratic decline. However, scholars do not yet agree on many basics.

Public-facing scholarship gives the impression that political scientists have reached a consensus that we are in a period of major democratic decline. However, scholars do not yet agree on many basics.

What Is the Appropriate Sample of Cases for Examining Backsliding?

The first major source of disagreement is the appropriate sample of cases for studying backsliding. In his contribution, Miller (Reference Miller2023) argues that the study of backsliding should be limited to only the sample of democracies. Other scholars have argued that it is crucial to understand backsliding in “important” and “influential” countries, such as the United States and Turkey, because these nations may affect the behavior of other countries. Many V-Dem reports use a global sample but weigh countries by population size, contending that it is more important to understand the experience of the “average global citizen.”Footnote 4 Much existing work on backsliding examines the unweighted global sample, including democracies and autocracies, and our main analysis uses this approach.

We believe that all of these samples are important to study as long as scholars are clear about the set of cases that they are examining and why. We do not find notable differences in the trends within democracies and autocracies on the measures we collect; however, in other cases, subsetting the world by regime type or regions may produce different results compared to a global average. Studying major or important countries is valuable because what happens in them may affect the overall status of democracy in the world. However, this potential influence is a hypothesis, not a reason to dismiss what is occurring in smaller countries.

Although including a global set of countries has been a common approach (including in our own article), there may be more to learn in future work by separating democracies and autocracies when we study backsliding. Luhrmann and Lindberg (Reference Luhrmann and Lindberg2019) designated the term “autocratization” to denote a decline of democratic qualities (i.e., essentially democratization in reverse), which can be applied to any country, regardless of regime type. However, due to the emergence of durable institutionalized autocracies in the post–Cold War era, it is not clear what constitutes a decline of democratic qualities in autocracies.

Modern autocracies exist on a spectrum from institutionalized regimes that adopt power-sharing institutions to personalist dictatorships in which one leader rules unconstrained (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Institutionalized regimes appear more democratic—they have parties, legislatures, and judiciaries—and leaders often share power with regime elites and opposition leaders through cabinet appointments, seats in the legislature, and policy concessions (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Meng, Paine, and Powell Reference Meng, Paine and Powell2023). Conversely, in personalist dictatorships, parties and legislatures often are banned, and elections (if they even are held) are tightly controlled (Gandhi and Sumner Reference Gandhi and Sumner2020).Footnote 5

Therefore, institutionalized autocracies clearly appear more democratic on the surface compared to personalist regimes and would be coded as such by most measures. However, studies also show that institutionalized regimes are the most durable form of autocracy (Meng Reference Meng2020). The adoption of seemingly democratic characteristics in the short term may hinder more complete democratization in the long term.Footnote 6 Furthermore, autocracies often rely on quasi-democratic institutions (e.g., political parties and courts) for repression, coercion, and citizen monitoring—functions that are fundamentally anti-democratic (Hassan, Mattingly, and Nugent Reference Hassan, Mattingly and Nugent2022; Shen-Bayh Reference Shen-Bayh2018).

This seeming paradox between the adoption of democratic institutions and their effects on stabilizing autocratic rule has been studied widely in the comparative authoritarianism literature; however, it has received less attention in the study of backsliding. Future work on trends in democracy should focus more attention on this key insight: that is, seemingly democratic institutions may be used as tools of control and cooptation, increasing the durability of autocracies.

Should We Use a Thick or a Thin Definition of Democracy?

Defining democracy is difficult. Scholars have always disagreed on whether a thick or a thin conceptualization of democracy is best. In our article, we adopted a quasi-minimalist definition that focuses on the role of electoral competition, which most scholars agree is a central component of democracy (Boix, Miller, and Rosato Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013, Norris Reference Norris2014; Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000). Other scholars prefer a thicker definition of democracy, in which civil liberties and rights protection also have a central role (Gorokhovskaia Reference Gorokhovskaia2023; Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023).

There likely will never be consensus on how expansive our view of democracy should be. Disagreements about definitions of democracy do not have to be a barrier to progress as long as scholars are transparent about which conceptualization they are using, why the measures that they use are appropriate for their definitions, and the implications for interpreting empirical findings and reaching theoretical conclusions.

However, regardless of whether scholars prefer a minimalist or more expansive definition of democracy, a key goal of future research should be to understand why—if the world truly is becoming less democratic in meaningful ways—backsliding does not show up in measures of electoral competition.

Why have election outcomes (e.g., the rate of incumbent turnover) remained largely the same since the early 2000s? On the one hand, it is possible that leaders are not making more attempts to subvert democracy. Our article presents data on election procedures and executive constraints suggesting that, at least on these dimensions, attempts to weaken institutions have not increased over time (Little and Meng Reference Little and Meng2023). However, we encourage scholars to collect more related data.

On the other hand, it is possible that leaders are attempting to weaken democratic institutions, but these attempts are backfiring because voters punish anti-democratic activity. As Miller (Reference Miller2023) notes, there seems to be a recent increase in mass protests following election results; however, this may be driven partly by differences in reporting standards.

Regardless, aggregate levels of electoral competitiveness have remained largely stable in the past two decades, and it is important that we understand which of these two very different pathways explains this empirical pattern.

How Should Backsliding Be Measured?

A third debate centers on how much to prioritize measures that rely less on expert judgment. All measurement strategies entail tradeoffs, and there is no “silver-bullet” solution (Munck and Verkuilen Reference Munck and Verkuilen2002). Furthermore, even if components of democracy can be measured objectively, the mapping of objective measures to the concept of democracy inherently requires subjective choices.

Objective measures have the advantage of being replicable and more reliably coded, but they may focus more on formal institutions, which are easier to observe. A fair critique of our article is that our objective measures capture only part of the picture, and perhaps substantial backsliding would be observed if we had collected more objective data on dimensions like civil liberties. However, as mentioned previously, even if this were true, researchers must explain why electoral metrics have not changed. If leaders have weakened rights protections, why are they not staying in power longer?

Expert-coded variables have the advantage of measuring a wider range of topics and concepts for which it is more difficult to collect objective data. However, as highlighted in our article, subjective measures may be vulnerable to coder bias—and this concern is especially pronounced when it comes to emotionally charged topics such as democratic backsliding, which has received considerable media attention (Treisman Reference Treisman2023). Moreover, it is difficult to check for bias because “only the expert coders know what specific events/factors motivate their coding decisions. Their scores are thus impossible to replicate or falsify. We must accept them on faith” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2023).

Two commentaries in this special issue (i.e., Bergeron-Boutin et al. Reference Bergeron-Boutin, Carey, Helmke and Rau2023 and Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023) and another recent paper (Weidmann Reference Weidmannn2023) present creative ways to check for specific types of expert bias, and we encourage future work to continue examining this issue. These analyses do not find evidence that those with more interest in coding (Bergeron-Boutin et al. Reference Bergeron-Boutin, Carey, Helmke and Rau2023) or coding after particular events (Weidmann Reference Weidmannn2023) are more pessimistic, or that those who change the coding become more pessimistic (Knutsen et al. Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023). We commend these efforts; however, as the authors acknowledge, none directly tests the specific type of time-varying bias that we propose. Furthermore, Treisman (Reference Treisman2023) outlines many possible sources of psychological bias that future work should continue to address. A parallel to the more familiar problem of making causal claims from regressions on observational data may be useful. That is, no matter how many confounding variables are controlled for, there may be an unobserved variable that leads to biased estimates. For certain goals, relying on experts making choices (or running unidentified regressions) may be the best we can do. However, if this is so, any conclusions drawn from the data should be transparent about the possible range of biases influencing the experts that we cannot necessarily specify, much less test for.

Another point of disagreement is whether the distinction between subjective and objective measures is exaggerated. Knutsen et al. (Reference Knutsen, Marquardt, Seim, Coppedge, Edgell, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Teorell, Gerring and Lindberg2023) argue that “seemingly objective measures often have considerable elements of subjectivity.” However, they recognize the difference between subjective and objective indicators in their own analysis. To address the possibility of coder bias, they examine “a spectrum of subjectivity within V-Dem’s indicators that might correlate with coder disagreement” and find that “coder disagreement systematically varies with levels of democracy and freedom of expression, but only for the highly subjective V-Dem indicators (v2elfrefair).” Furthermore, the V-Dem codebook distinguishes between “(A) variables,” which are coded by project managers and research assistants and are “factual in nature,” and “(C) variables,” which are coded by country experts. The measurement model treats these variables differently, assuming that only the latter are observed with noise. We frankly find it puzzling that leaders of the V-Dem project have argued so strongly against our distinction between subjective and objective measures when their own data make a distinction that is exactly the same as ours in practice only with different labels.

In summary, we can disagree about the details of whether individual variables are best classified as objective (which arguably is a subjective determination!) or whether the most appropriate distinction is between objective and subjective, between factual and expert-coded, or some other terminology. Scholars also can disagree about how much to weigh this factor (whatever we want to call it) when deciding on which democracy indicators to focus. However, this need not lead to a nihilistic viewpoint that everything is subjective or that we do not need to prioritize collecting objective measures. Collecting objective data on all dimensions of democracy may be challenging; however, if we aspire to answer these questions scientifically, it must be a central goal. In fact, with recent improvements in technology for collecting and processing data, we should be expending more effort for gathering objective data to encompass dimensions of democracy not included in our article, including civil liberties, rights protections, and other types of executive aggrandizement.

Collecting objective data on all dimensions of democracy may be challenging; however, if we aspire to answer these questions scientifically, it must be a central goal.

Standards of Evidence

Finally, a question that has hovered in the background of this debate and that deserves more attention is: “What is the appropriate evidentiary standard required to claim that the world is becoming less democratic?” Empirical claims in the social sciences typically take the form of some type of hypothesis test, taking into account uncertainty driven by sampling or measurement error. In contrast, research that relies on global averages (including our article) typically examines trends without discussing any uncertainty. An admirable aspect of the V-Dem measurement model is that it reports uncertainty about estimates, which would allow scholars to conduct hypothesis testing on changes in democracy trends.Footnote 7

Although we certainly do not advocate ignoring changes in aggregate democracy scores unless a particular null hypothesis can be rejected, strong claims typically require strong evidence, especially in the contemporary practice of political science. These conventional standards, however, have not been uniformly applied to studies of democratic backsliding. For instance, Weitzel et al. (Reference Weitzel, Gerring, Pemstein and Skaaning2023) claim that their findings constitute “evidence of democratic backsliding using all three indices,” which “validates conventional wisdom.” Yet, they also point out that the changes that they document are “miniscule” and are well within the standard errors of the estimates they produce. Miller (Reference Miller2023) claims that “the clear weight of existing quantitative evidence localizes recent democratic decline to democracies.” To back this up, he presents trends in changes in democracy scores subsetted by regime rather than a more conventional systematic hypothesis test that these trends are different (in fact, to us, they look broadly similar).

We can argue that backsliding is so important that any change in point estimates is worth addressing, but we should be clear that this conventional wisdom rests on evidence that is well below the bar that we typically use for making empirical claims.

OTHER PATHS FORWARD

We conclude this article by discussing promising directions for future research motivated by the comments on our article.

Collect More Data

A clear path forward is to collect more objective data that might capture aspects of democratic backsliding absent from our article. In our experience, those who are skeptical of our research point to specific events that they believe to be emblematic of the world becoming less democratic (e.g., weakening bureaucracy in India and the January 6 breaching of the US Capitol) but for which there is no systematic data to test whether the event in question is part of a wider trend. The data collected by Baron, Blair, and Gottlieb (Reference Baron, Blair and Gottlieb2023) provide examples of many classes of events in which scholars could provide complete global coverage, including attacks on judicial independence and reductions in civil liberties.

Another potentially promising area to explore is governmental control of the media. Barrie et al. (Reference Barrie, Ketchley, Siegel and Bagdouri2023) propose a method to use text analysis for detecting the amount of criticism that potentially could be applied more widely. It also would be valuable to systematically collect data on government ownership of media outlets. Even if any particular approach is imperfect, what matters for detecting backsliding is that the measure is sufficiently reliable to detect changes over time within countries.

Improve Expert-Survey Methods

Another potential direction for future work is to continue the types of methodological innovations highlighted in this special issue. A relatively strong aspect of V-Dem is that it is based primarily on more specific questions than previous democracy scores. We expect that more specific questions likely will exhibit less disagreement and be less biased—a hypothesis that could be explored. If so, future surveys of experts also can lean toward providing more concrete and specific questions.

Weitzel et al. (Reference Weitzel, Gerring, Pemstein and Skaaning2023) also provide a creative way to combine objective measures with expert coding. In addition to extending that approach, future work could integrate these different sources with a methodology such as that described by Fariss (Reference Fariss2014).

Study Democratic Resilience

On the substantive side, we encourage future work to continue studying sources of democratic resilience. Although any amount of backsliding is a reasonable cause for concern, it is helpful to recognize that the proportion of countries in the world that are democracies is at (or at least near) an all-time high (Treisman Reference Treisman2023). This is not a trivial achievement—for most of human history, authoritarianism has been the dominant mode of governance in the world. Furthermore, as Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2023) point out, “Global democracy has confronted serious threats during the past two decades….Given these developments, the fact that the majority of the world’s democracies have survived during the past two decades suggests a striking degree of democratic resilience.”

Democratic resilience is itself an important topic, but it also is highly connected to the study of backsliding simply because many backsliding attempts do fail. It is important for us to understand how and why. In addition, scholars should study cases of backsliding attempts and democratic resilience that occurred before 2016. As our article reveals, the highest number of (successful and unsuccessful) attempts to subvert constitutional term limits occurred in 2006—before most scholars were focusing on the topic of backsliding. Studying earlier periods of backsliding and resilience provides a more complete and accurate picture of the constant push and pull of democracy that has always existed.

We Need to Admit When We Do Not Know!

Regardless of how future work on backsliding progresses, we want to conclude by reiterating the importance of recognizing what we do and do not know about the topic of democratic backsliding. Admitting uncertainty is particularly crucial when studying issues such as backsliding that draw wide attention outside of academia. Journalists seek surprising findings and tidy narratives, and the most confident voices often will receive the most attention. When highly publicized claims about political science research turn out to be unfounded, we collectively lose public trust.

Our point is not that we do not know anything about democratic progress and backsliding. For example, all democracy measures (regardless of their criteria) document major changes in global democracy following the end of the Cold War; this consensus is backed by solid empirical evidence. Scholars and activists who are raising the alarm about democratic backsliding today will have more credibility if they clearly differentiate between claims with strong empirical basis and those that rely on untested assumptions, such as experts applying consistent standards across time.

Even within the confines of academic studies, understanding uncertainty—particularly about fundamental issues of measurement—is crucial to scientific progress. As we hope the contributions to this special issue and our response make clear, doing so provides a sense of where future efforts are more likely to yield results.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.