Twitter has been a prominent forum for academics communicating online, both among themselves and with policy makers and the broader public. Twitter thus has had a significant role in the practice of social scientific research in the 2010s and early 2020s.

The growth of this online academic community has weathered a number of changes in how the platform operates, but perhaps none have been as dramatic as the takeover by Elon Musk in the Fall of 2022. Musk’s ownership brought a range of changes to the platform, including mass layoffs at Twitter; the reinstatement of ex-president Donald Trump’s account, which had been deactivated following its role in the January 6, 2021, riots at the capitol; the reinstatement of tens of thousands of accounts that had been suspended for violating the platform’s Terms of Service; the corresponding permission of posts containing mis/disinformation that previously had been barred; as well as a general weakening of the enforcement of these scaled-back policies (Dang Reference Dang2023; Rutenberg and Conger Reference Rutenberg and Conger2024). Given subsequent developments in global politics, these changes enabled a less-moderated conversation around topics of interest to social scientists including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Hamas attacks on Israel and subsequent conflict in Palestine, and ex-president Trump’s legal battles. Each of these changes influenced the broader social-network characteristics in ways that are not yet fully understood, quantitatively, but which entailed a shift in the user experience that we colloquially refer to as “vibes.”

This article asks and answers a simple research question: Did Elon Musk push academics away from the platform? Anecdotal evidence of a broader move off Twitter is abundant, perhaps best exemplified by the pervasive inclusion of profile names for alternative social media platforms in user bios after Musk’s takeover. But how widespread was the desertion? When, exactly, did it happen? Moreover, and perhaps most important, who was most likely to reduce their use of the platform?

Using a snowball sample of academics across the fields of political science, economics, sociology, and psychology, we show that there was a substantively significant reduction in engagement with the platform, especially in terms of original tweets and quote tweets.Footnote 1 Furthermore, we show that the accounts most responsive to Musk’s takeover were higher profile, as proxied by the (original) blue check that indicated verified accounts. The reduction in engagement from these accounts is arguably more damaging for Twitter and is almost certainly a greater opportunity cost for the account holders who had developed substantial online reputations using these accounts.

…we show that the accounts most responsive to Musk’s takeover were higher profile, as proxied by the (original) blue check that indicated verified accounts.

Conversely, the greater visibility of these accounts also may have increased the social pressure to abandon the platform and signal objections to Musk’s various decisions. These included reactivating alt-right accounts that had been deactivated by Twitter’s previous moderators and, most notably, inviting ex-president Trump back to the platform on which he had built his reputation. The vibes on academic Twitter certainly have changed, and this article provides a quantitative answer to the questions of “When, exactly?” and “For whom?”

The vibes on academic Twitter certainly have changed, and this article provides a quantitative answer to the questions of “When, exactly?” and “For whom?”

THE ROLE OF TWITTER IN SCHOLARLY COMMUNICATION

To understand why Elon Musk’s ownership of Twitter might drive academics from the platform, it is important to note its utility that academics may have obtained in the first place. Twitter has been a prominent forum for academics communicating online among themselves (Klar et al. Reference Klar, Krupnikov, Ryan, Searles and Shmargad2020), with policy makers and the broader public (Jester Reference Jester2022; Jünger and Fähnrich Reference Jünger and Fähnrich2020), and even with their students (Sweet-Cushman Reference Sweet-Cushman2019).

Thus, Twitter has had a significant role in the practice of academic and particularly social scientific research in the 2010s and early 2020s. Ke, Ahn, and Sugimoto (Reference Ke, Ahn and Sugimoto2017) found that Twitter use is most common among social scientists; we restricted our analysis to academics in the disciplines of political science, economics, sociology, and psychology.

Has this been a positive development? Perhaps it is too soon to know. In broad strokes, some observers point to Twitter as a site for revolutionary political organization by marginalized groups (Tufekci Reference Tufekci2017) or for direct democratic communication between elected officials and constituents (Barberá et al. Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019). For other observers, Twitter precipitates the decline of traditional party organization and the bedrock liberal values of toleration and free speech (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2019).

In more concrete terms, existing research paints a mixed picture. On the one hand, Twitter undeniably has increased the volume and visibility of academic communication, enabling public conversations that otherwise would have remained within faculty lounges or not taken place at all. In Grossmann’s (Reference Grossmann2021) account of recent social science reforms, Twitter has an important role in enabling conversations about research best practices that include the recent “credibility revolution” and conventions around preregistration, data sharing, and open access publication.

Twitter also has provided opportunities for scholars from diverse fields and different levels of seniority to interact. Searles and Krupnikov (Reference Searles and Krupnikov2018) provided valuable advice for faculty mentors to guide their graduate students on how to use the platform to promote their work—for example, illustrating how existing seniority hierarchies were made more porous on Twitter. Especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Twitter was a valuable resource to preserve existing academic networks for knowledge dissemination. Bandula-Irwin and Kitchen (Reference Bandula-Irwin and Kitchen2022) described how the platform could be used as a replacement for traditional in-person conferences. Given that the pandemic seemed to disproportionately affect female academics’ continued productivity (Kim and Patterson Reference Kim and Patterson2022), Twitter may have prevented the problem from being exacerbated further.

On the other hand, many of the structural inequalities associated with legacy academia are reproduced on Twitter, with women and junior scholars being less central and less amplified than their male peers (Bisbee, Larson, and Munger Reference Bisbee, Larson and Munger2022). There is also evidence that this is true for the related case of journalists on Twitter (Usher, Holcomb, and Littman Reference Usher, Holcomb and Littman2018).

However, beyond these broader descriptions, Twitter is a social network where academics can feel seen by their peers, learn in-group signifiers, and express themselves in ways that produce positive feelings of solidarity (Jünger and Fähnrich Reference Jünger and Fähnrich2020). In this sense, the academic Twitter community operates according to the same psychological incentives as any other online community (Bail Reference Bail2021). Moreover, for most of Twitter’s existence at least, the broader platform was characterized by many of the qualities of the social science community: it was younger, better educated, and more progressive in its politics (Pew Research Center 2018).

THE MUSK EFFECT

Why might Elon Musk’s acquisition of the corporation have driven academics off the platform? There were numerous significant policy changes, including changes to Twitter’s verification process, regulations on account names, and removal of the free Application Programming Interface (API) that many scholars had relied on for empirical research across a range of areas of scientific inquiry.

Some academics also expressed distaste for Musk’s vibe. Musk had long used the platform in ways that many academics disliked. His use of Twitter’s “polls” feature to determine several of his early policies evinced an unscientific understanding of the principle of random sampling. He endorsed and amplified dangerous and unfounded conspiracy theories about US elected officials. More broadly, he demonstrated a puerile childishness that often was at odds with the predominantly liberal worldview and the at least nominally staid professionalism of Twitter’s academic community.

We argue that a combination of these features of the threat and then the reality of Musk’s ownership of the Twitter corporation influenced academics either to quit Twitter altogether or at least reduce their engagement with the platform (i.e., “disengage”). The policy changes and personality of Twitter’s new owner were difficult to avoid and may have made the experience of using the platform less palatable. Conversely, these same attributes may have stimulated a type of ideological boycott, in which academics disengaged with Twitter as a political strategy to indicate their intellectual and moral opposition. We expected this pressure to be greater among more popular users because the visibility of their continued use of the platform (and the assumed tacit endorsement of it) would be greater. However, these same users also are more sensitive to a sunk-cost logic in which the prospect of shutting down a “valuable” Twitter account is more costly.

Data limitations rendered a careful analysis of these mechanisms beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, we examined heterogeneous effects in our analysis, finding that more popular accounts were more likely to disengage following Musk’s takeover. These patterns are consistent with the social-pressure explanation for disengagement described previously, although we acknowledge the limitations of a causal interpretation of our data.

DATA AND METHODS

In early 2021, we used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to begin the process of collecting what we believed to be the most comprehensive dataset of US-based social scientists on Twitter. This procedure had several steps, which are described in the online appendix.

The collection and analysis of substantial quantities of social media trace data are now de riguer across the quantitative social sciences as well as many other realms of social, political, and economic life. Thousands of peer-reviewed academic studies use the same methods that we used in our study. As is common in these studies, our respective Institutional Review Boards deemed our research exempt from full review. Nevertheless, there were legitimate concerns about the ethics of potentially causing public scrutiny of social media users who are not accustomed to (and who obviously are not seeking) attention beyond a local network. For this reason, this article does not identify any accounts by name and our replication materials anonymize the accounts (Bisbee and Munger Reference Bisbee and Munger2024).

Our analysis consisted of a series of descriptive results, relying on a before and after comparison of several different measures of engagement with the platform to reach a causal conclusion. These measures included the number of active accounts on Twitter; the frequency with which they were tweeted; and the levels of engagement with their content, measured as either likes, retweets, replies, or quote tweets.

For simplicity, we focused on Elon Musk’s official takeover on October 28, 2022, as the cut point around which to compare before and after changes in academic use of the platform. However, we also implemented a Bayesian Change-Point Analysis (BCPA) that located the structural break in Twitter usage by academics around November 19, 2022—which happened to be the date when Musk announced he would reinstate Trump’s Twitter account (see figure 4).

Causally identifying Musk’s impact on social scientists on Twitter is complicated by two alternative narratives. The first is that Musk’s ownership began just prior to the standard academic winter break, during which social scientists naturally disengage from the platform, thereby rendering spurious any empirical association that we documented. The second narrative is the potential for reverse causality. It is difficult to imagine that social scientists would have any influence over Musk’s interest in purchasing the platform or the previous owners’ interest in selling. However, there was a steady decline in engagement among our sample that mirrored a broader disengagement that paved the way for Musk’s takeover.

We implemented various methods to address these concerns, but we do not claim that our findings are perfectly causally identified. First, we calculated a per-account change in activity between the weekly data we measured in 2022 relative to data observed during the same week in 2021. Although this approach is coarse, it does account for seasonal variation in engagement that otherwise might produce a dramatic but spurious association between Musk’s takeover and engagement among users in our sample.

Second, we allow the data “speak” by implementing the BCPA method. This method detects structural breaks in time-series data under the assumption that observations are drawn from one of two independent and identically distributed random processes. We bootstrap sampled 5,000 accounts at a time to demonstrate that the method selected November 18, 2022, in 71.5% of these bootstrapped samples as the break point separating one era of social-scientist engagement with the platform from another. It is important to note that this was one month after Musk’s official takeover, suggesting that it is unlikely to reflect a reverse-causality narrative in which declining academic engagement prompted Musk’s interest. More tellingly, this breakpoint coincides with Musk’s promise to reinstate ex-president Trump’s Twitter account, which previously had been suspended by the previous ownership on January 8, 2021, in response to his role in the Capitol riots.

Third, we implemented a simple difference-in-differences specification with account fixed effects, subsetting to one month before and following the cut point identified using the BCPA method. The first difference, estimated with account fixed effects, cubic polynomial time trends, and subsetting to a period just prior to and just following Musk’s takeover, provides further evidence against the alternative explanations for the association between Musk’s ownership and social science’s Twitter disengagement. Our second difference is of theoretical interest, examining whether verified accounts were more or less likely to disengage,

RESULTS

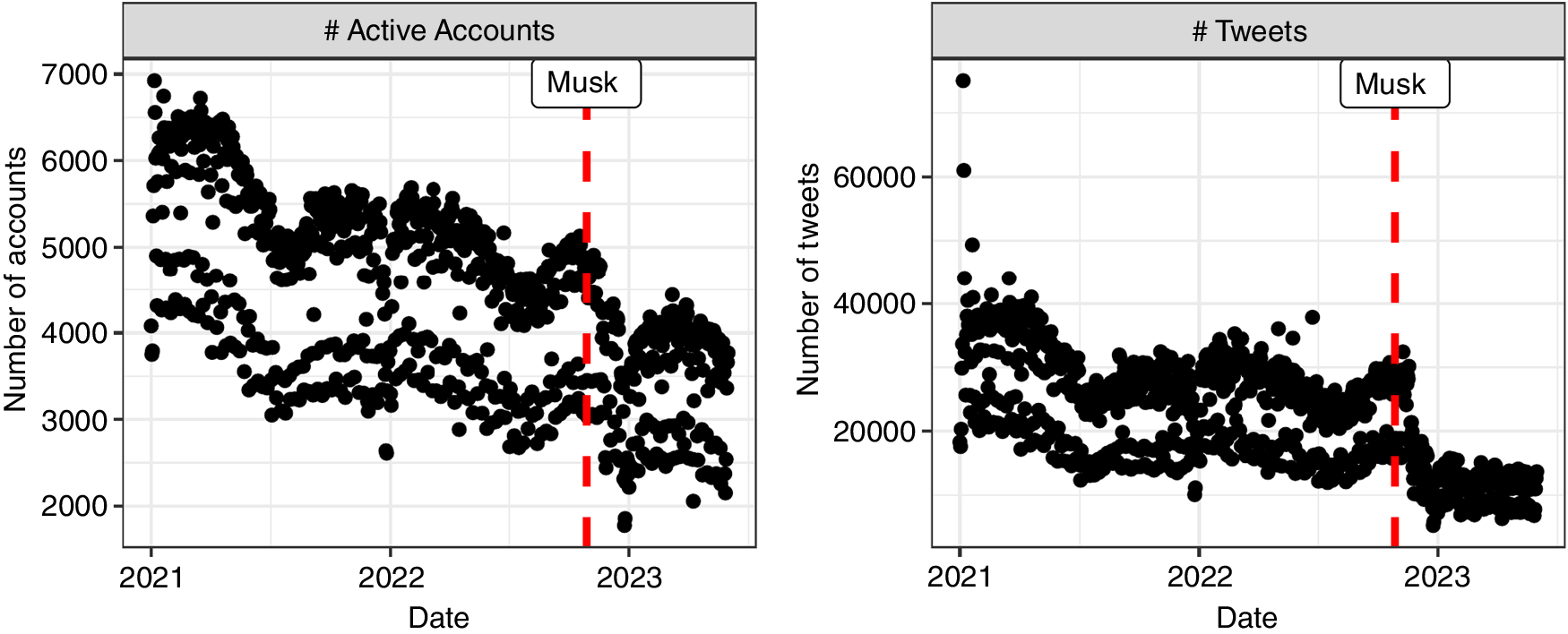

Was Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter concurrent with a decline in the academic community of scholars who had been using the platform to share and discuss research? A simple overtime plot of the number of users posting on a given day suggests that the answer is a qualified “yes.” The left panel of figure 1 illustrates that although the average number of daily active accounts had been declining since 2021, it experienced a dramatic decrease in early November 2022, just as Musk took over. More strikingly, the level of engagement with the platform—operationalized by the total number of tweets written by academics (see the right panel of figure 1)—exhibited an even more precipitous decline slightly later in November.

Figure 1 Descriptive Time-Series Plots of Academic Use of Twitter

The left panel depicts the total number of users who posted each day. The right panel depicts the total number of tweets posted each day. Vertical dashed lines indicate the date that Elon Musk officially took over Twitter ownership on October 28, 2022.

However, Musk’s takeover occurred just prior to the typical academic winter break. As previous years illustrate, this generally is a period of reduced Twitter activity in our social science Twitter sample, with especially pronounced reductions during the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day. The 2022/2023 winter-break period, however, exhibited a stronger decline than that observed in the 2021/2022 break, which began much earlier than the preceding year (i.e., around the time of Musk’s takeover) and exhibited no evidence of a sharp rebound to pre-break levels.

Nevertheless, it may be that the decline in both active users and average tweets per day that is associated with Musk’s takeover is simply a spurious correlation driven by a seasonal trend. To investigate this claim, we calculated a per-account annual change by week. Specifically, for each of our 15,000 accounts, we first calculated their average activity per week and then the annual change measuring how many tweets were written in a given week in 2022 versus those written by the same user in the same week of 2021. Of course, many other factors are involved, such as changes in an individual’s position in the academy. Nevertheless, with 15,000 accounts on which to draw, we argue that these individual-level factors should produce more or less random variations and therefore be attributed to attenuation bias, which our large sample is sufficient to overcome.

These annual comparisons are presented in figure 2, in which the bars are green if 2022’s weekly average engagement was higher than the same week in 2021 and red if it was lower. Again, despite other fluctuations over the course of the year, the decline following Musk’s takeover is stark and persistent. Specifically, the post–Musk takeover experienced the second-greatest decline in average weekly tweets for all of 2022 relative to 2021. The only week with a larger decline was the first week in January, the 2022 engagement of which is compared to the Capitol riots on January 6, 2021, which produced a flurry of tweets from social scientists of all disciplines. Even after controlling for seasonal trends by calculating the annual change in activity, we still noted a striking decline in academic Twitter use that co-occurred with Musk’s takeover.

Figure 2 Account-Level Change in Tweets Posted Per Calendar Week

Bayesian Change Point Analysis

Thus far, we have relied on descriptive plots that suggest that academics reduced their use of Twitter in response to Elon Musk’s takeover. Although the patterns are striking, this approach nevertheless prevents us from making inferential statements about these patterns absent our assumption that October 28, 2022, is the pivotal cause. To overcome this limitation, we turn to the BCPA method. (For more detail, see the online appendix.)

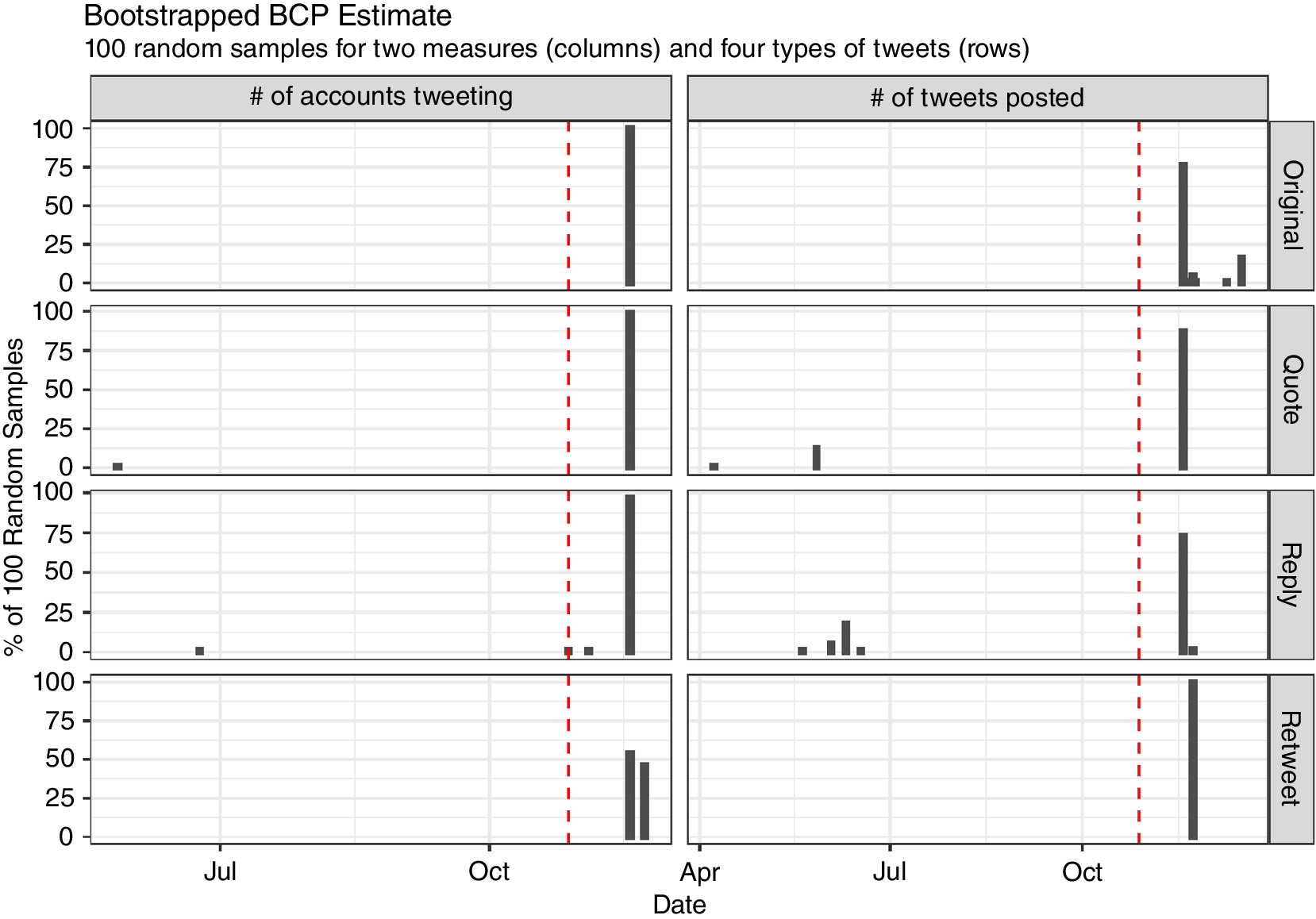

Figure 3 visualizes the results in which the y-axes indicate the number of bootstrapped simulations in which each date (x-axes) was chosen as the break point. Taken together, there is clear and consistent evidence that the period between November 18 and 23, 2022, was when the academics who comprised our social science sample disengaged from the platform.

Figure 3 Agnostic Estimation of Structural Break in Tweeting Activity

Bootstrapped BCPA estimate. 100 random samples for two measures (columns) and four types of tweets (rows).

This period is proximate to Musk’s takeover on October 28, 2022, but clearly with somewhat of a lag. A review of the events of the period provides a post hoc explanation: November 19, 2022, was the date that Musk reinstated Trump’s Twitter account and announced it with the tweet shown in figure 4. Although Musk’s actions during the second half of 2022 were regularly norm breaking, for many social scientists, the idea of allowing Trump back on the platform may have been the last straw (not to mention Musk’s hubris and statistical ignorance for thinking that his “poll” measured the voice of the people). In the subsequent analyses, we used November 19, 2022, as the inflection point to evaluate heterogeneous effects by account type.

Figure 4 Musk’s Tweet Announcing the Decision to Reactivate Donald Trump’s Twitter Account

Who Left?

As discussed previously, we posit that the decision to disengage from the Twitter platform was a function of the account’s popularity; however, this intuition can be interpreted in one of two ways. To test it, we separated our data by whether an account was verified before November 30, 2022—that is, when a blue check still meant more than a willingness to pay the $8-per-month fee.

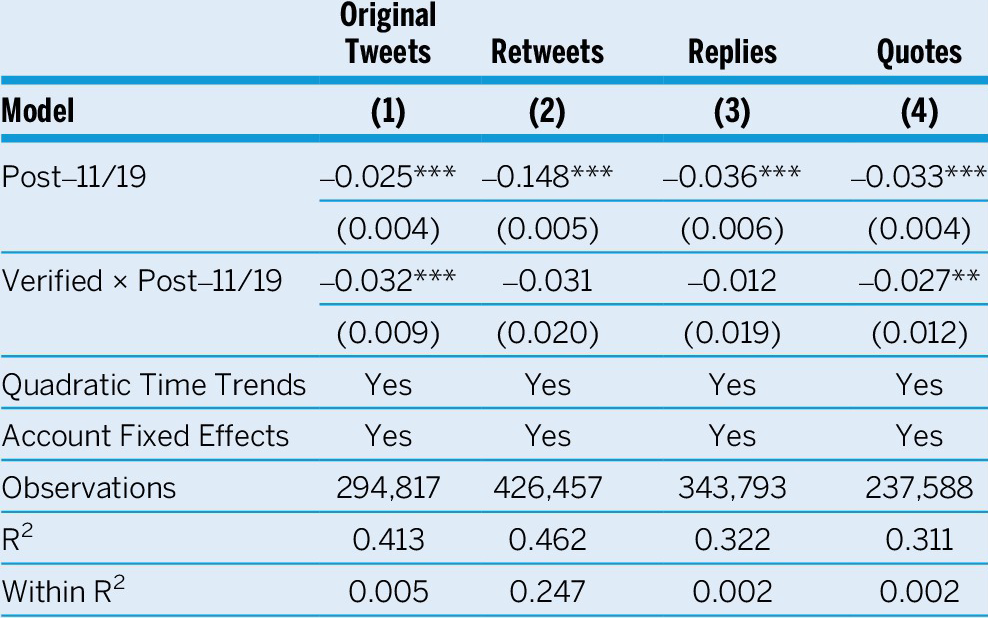

The columns in Table 1 present the results for each tweet type, highlighting that verified users were significantly more likely to reduce their engagement on the platform—but only in terms of original tweets (column 1) or quote tweets (column 4). Across all specifications, the Post t indicator is negative and significant, which demonstrates that—within users—engagement decreased significantly after November 19, 2022, relative to October 1, 2022.

Table 1 Logged Tweets per Day Predicted by Period Interacted with Verified Accounts

Notes: Clustered (account) standard errors are in parentheses. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1.

These results are consistent with a reputational mechanism by which the most visible members of the academic community on Twitter (i.e., those with verified accounts) reduced their engagement with the platform more than less-visible accounts. However, these conclusions hold only for the more reputational behaviors of authoring original content (column 1) or quoting another’s tweet (column 4). Conversely, we observed no significant difference between verified and unverified accounts regarding retweeting and replying to tweets, although both of these are in the same direction. If we were to imagine a range of behaviors on Twitter from most to least reputational, it would be arrayed from original posts, quote tweets, replies, retweets, and finally favorites (which we could not measure in our data). As such, the patterns we document in this article seem to indicate that all academics in our sample reduced their engagement with the platform. However, this reduction was substantially more pronounced among those whose visibility carried more significant implications for their reputation and among behaviors that are more reputational in nature.

DISCUSSION

We documented suggestive evidence of academics across four social science disciplines who disengaged from Twitter just as Elon Musk took over ownership of the platform. We found that both the number of daily active accounts and the volume of content that was posted declined significantly following his takeover. Using the BCPA method, we further concluded that the actual decrease did not occur until around November 19, 2022, three weeks after Musk’s official tenure began and corresponding to his poll-driven decision to reinstate ex-president Donald Trump’s account. Finally, we show that the decline in engagement was stronger among “verified” academic accounts, especially in the behaviors that create original content: that is, writing original tweets and quote-tweeting existing tweets.

We argue that these patterns are consistent with a simple narrative in which Musk’s ownership brought about changes in the social network that reduced the utility obtained by those academics using it. In addition, the significantly greater declines in engagement among more popular accounts were consistent with a reputational driver, wherein scholars with larger profiles may have been more concerned about being perceived as tacitly endorsing the platform. We have not been able to experimentally manipulate anything in our study, including this potential reputational mechanism; therefore, we call on future research to evaluate more carefully our explanations for why academics reduced their use of Twitter after Musk’s takeover. Given the lack of a dedicated API to collect data (one of many of the onerous changes made by Musk), future studies may need to rely on smaller-N approaches via survey experiments or qualitative studies.

An obvious question is: “Who cares?”Footnote 2 We contend that those who value Twitter specifically and public-facing academic research more generally should care about these results. Although the net effect of Twitter on political and intellectual life will continue to be debated, as summarized previously, there are many parties that will be affected by the decline of academic Twitter.

Those who believe that Twitter generated fruitful discussion about working papers should care about the evidence presented in this article. Those who became aware of junior scholars’ research that they otherwise would not have should care, as should those who were introduced to academics from underrepresented backgrounds in the academy. Furthermore, the nonacademics who were introduced to and followed the scholars in our dataset also should care, as well as anyone who values the principle of independent research reaching a wider, nonacademic audience.

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there are many scholars who never used Twitter in the first place and that the institutions that govern professional advancement remain mostly insulated from new channels of networking and influence such as those embodied by Twitter. Furthermore, it is possible that the decline we have documented will be temporary and that those who were pushed off the platform by Musk’s ownership may return one day. As with any research that focuses on online social networks, we expect that our conclusions are fleeting—but we argue that the dynamics governing the patterns that we documented are durable.

This is the part of the article when we normally would “punt” the outstanding questions to “future research.” Except in the case of Twitter at the time of writing, our capacity to conduct the type of analyses we have described has been destroyed. Free access—academic or otherwise—to Twitter’s APIs is no longer possible.

This is the part of the article when we normally would “punt” the outstanding questions to “future research.” Except in the case of Twitter at the time of writing, our capacity to conduct the type of analyses we have described has been destroyed.

Even the skeptic who might not be very concerned about the decline of social scientists on Twitter should be concerned about the decline in transparency that has accompanied Musk’s leadership caused by the removal of API access. This decline is mirrored across a number of prominent online information environments, weakening the ability of noncorporate actors—including journalists and social scientists—to study how these ecosystems contribute to society writ large.

We note that this API access removal was not a total shock: Freelon (Reference Freelon2018) predicted the coming “post–API era” more than five years ago. As Munger (Reference Munger2023) argues, this type of “temporal validity” problem is a first-order concern for research on fast-moving systems such as social media. Therefore, social scientists cannot take stability for granted but rather should embrace more epistemically humble research methods such as quantitative description (Munger, Guess, and Hargittai Reference Munger, Guess and Hargittai2021).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096524000416.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FH59GV.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.