Political science professors face challenges teaching an increasing number of students using traditional instructional strategies that students often consider uninteresting (Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015). As a result, a growing number of faculty strive to develop creative techniques and implement experiential-learning methods in the classroom to maintain student engagement and increase learning (Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015; Bromley Reference Bromley2013; Lay and Smarick Reference Lay and Smarick2006). Among these methods are simulations, which have become increasingly popular among political science faculty (Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2010, Reference Baranowski and Weir2015; Fitzhugh Reference Fitzhugh2014; Lay and Smarick Reference Lay and Smarick2006; Mariani Reference Mariani2007; Pappas and Peaden Reference Pappas and Peaden2004) on a diverse set of topics (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2013; Biziouras Reference Biziouras2013; Bridge Reference Bridge2013; Frombgen et al. Reference Frombgen, Babalola, Beye, Boyce, Flint, Mancini and Eaton2013; Glasgow Reference Glasgow2015; Hunzeker and Harkness Reference Hunzeker and Harkness2014; Jiménez Reference Jiménez2015; Pallister Reference Pallister2015; Rinfret Reference Rinfret2012; Switky Reference Switky2014; Woessner Reference Woessner2015).

In political science, simulations have been found to be effective pedagogical tools in teaching civic education, campaign processes, electoral processes, and legislative processes (Bernstein and Meizlish Reference Bernstein and Meizlish2003; Caruson Reference Caruson2005; Deitz and Boeckelman Reference Deitz and Boeckelman2012; Fuller Reference Fuller1973; Kathlene and Choate Reference Kathlene and Choate1999; Lay and Smarick Reference Lay and Smarick2006; Pappas and Peaden Reference Pappas and Peaden2004; Sands and Shelton Reference Sands and Shelton2010). Research indicates that simulations enhance student understanding of difficult materials, complex political concepts, interest, reality, skills, and motivation in a way that traditional methodologies often cannot achieve (Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015; Caruson Reference Caruson2005; Fuller Reference Fuller1973; Mariani Reference Mariani2007; Pappas and Peaden Reference Pappas and Peaden2004; Wedig Reference Wedig2010).

This article describes a new simulation activity for teaching about campaigns and elections, specifically focusing on campaign finance. It also reports the extent to which the simulation is linked to student perceptions of campaigns, elections, and political involvement, as indicated by results from several years of post-activity debriefs with simulation participants.

SIMULATING CAMPAIGN FINANCE

To create the simulation, we took inspiration from Sampson v. Buescher, a federal lawsuit on the topic of the complexities of campaign-finance laws. In brief, Sampson involved a small group of neighbors, led by Karen Sampson, who opposed the annexation of their Colorado neighborhood into a nearby town. After they posted a few handmade yard signs and talked to their neighbors, an annexation proponent sued them for operating as a ballot-issue committee without registering with the state. Colorado law required that any group that collectively spent more than $200 to speak on a ballot issue was to register as an issue committee and comply with all of the sundry requirements that accompany it (e.g., completing campaign-finance forms, tracking and reporting all contributions and expenditures, and opening a bank account). The neighbors knew nothing of campaign-finance laws, and when they attempted to comply, they were soon overwhelmed by the requirements. They eventually challenged the federal constitutionality of the state’s campaign-finance laws as a burden on free speech and association.

To introduce these issues to students, we designed a classroom simulation in which they are assigned to “community groups” that attempt to convince their neighbors how to vote on a forthcoming ballot issue. As far as the students know, this is the sum total of their task at the beginning of the exercise. It is only when each group spends more than $200 that the campaign-finance element is triggered and they must comply with all of the various requirements.

As such, the exercise is designed to help students—who typically receive a disproportionate exposure to theory in political science—gain greater awareness and appreciate the practical realities of (1) engaging other people on issues; and (2) a little-known element of electoral campaigns—campaign-finance laws—particularly in the context of ballot-issue campaigns (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2009).

The focus of the simulation is twofold: (1) introducing campaign-finance laws—with a particular emphasis on disclosure—and compliance requirements associated with these laws; and (2) compelling students to think about how to engage their fellow citizens. As such, the exercise is designed to help students—who typically receive a disproportionate exposure to theory in political science—gain greater awareness and appreciate the practical realities of (1) engaging other people on issues; and (2) a little-known element of electoral campaigns—campaign-finance laws—particularly in the context of ballot-issue campaigns (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2009).

Campaign finance, of course, is a large and debated topic, spanning candidate and ballot-issue contexts; recent US Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Citizens United v. FEC); the role of money in politics (Gaughan Reference Gaughan2016; Gerken Reference Gerken2014; Krumholz Reference Krumholz2013; Mayer Reference Mayer2016); and the efficacy of disclosure (Hasen Reference Hasen2011; Munger Reference Munger2009; Primo Reference Primo2013; Primo and Milyo Reference Primo and Milyo2006; Wood and Spencer Reference Wood and Spencer2016)—to name only a few. By necessity, a simulation created to be implemented within the confines of one class meeting must be narrowly focused. Thus, drawing on Sampson v. Buescher and placed within the context of discussion and debates about compliance with disclosure in ballot-issue campaigns (Carpenter and Milyo 2012–Reference Carpenter and Milyo2013; Gardener Reference Gardener2012; Kang Reference Kang2013; Milyo Reference Milyo2007; Youn Reference Youn2013), we chose to focus the simulation on the experience of common citizens rather than experienced political participants.

This is not to ignore issues of disclosure (or its relative absence) associated with corporations, unions, large nonprofits, and other entities in the wake of Citizens United (Dowling and Wichowsky Reference Dowling and Wichowsky2013; Potter and Morgan Reference Potter and Morgan2013; Torres-Spelliscy Reference Torres-Spelliscy2011). We expect these issues to be discussed among other disclosure-related topics in which our simulation would be placed, and perhaps someone else will develop and report on a simulation focused on “dark-money” campaigns. Although we focus the simulation on compliance within the context of campaign-finance disclosure laws, similar issues may be present with compliance in other contexts, such as opening a business, running a large public fundraiser, and other circumstances in which citizens must navigate a potentially challenging bureaucratic landscape. Thus, the framework of our simulation could be adapted to numerous other contexts.

HOW IT WORKS

This section briefly describes simulation activity. Detailed instructions and materials are provided in the online appendix.

At the beginning of a two-hour-and-40-minute class, students are assigned to one of multiple groups (ideally, four to five students per group). They are told that their task is to determine a way to convince their neighbors how to vote on a measure that will appear on the ballot six days hence. Each group is given a scenario to guide their actions. Some groups are supposed to convince their neighbors to vote for and others to vote against the measure. The activity lasts two hours. The first half-hour is dedicated to groups planning their campaign efforts. The remaining time is divided into six 15-minute blocks, each representing one day, during which students implement their plans.

Materials are purchased from a “store” using the money that each member of each group is given. The reality of the simulation is heightened by using actual materials, such as t-shirts and fabric markers. As groups make purchases from the store, the total money spent is tracked by storekeepers to determine when a group exceeds the $200 threshold. When this happens, the activity stops and groups are introduced to the campaign-finance requirements with which they now are required to comply. This is accomplished by giving each group a state’s actual multi-hundred-page campaign-finance manual, as well as all relevant forms (available on state websites).

They also are provided the “assistance” of another person in the room to whom they were not introduced at the beginning of the simulation: a representative of the “secretary of state.” Much like a state elections division, the representative is available to answer questions as students complete the necessary campaign-finance documents. The representative also tracks mistakes made by groups as they submit (or do not submit) the required forms and tallies fines. When we implement this activity, we fill this role with a local attorney who is an expert in campaign-finance law.

After the simulation resumes, groups have two responsibilities: (1) designing materials for what are now officially campaigns, and (2) complying with state campaign-finance laws. To further increase the realism of the activity, each “day” in the simulation introduces new complexities that require greater attention to campaign-finance laws, including receiving unsolicited donations and anonymous cash contributions, offers to pay for political rallies, and requirements to submit necessary forms by prescribed deadlines. Many but not all of these complexities require that groups review the laws to determine what to do.

After the activity, we lead a debrief during which the instructor solicits perspectives from students about (1) the activity, and (2) the political phenomenon that the activity is designed to simulate. Results of these debriefs are reported in the next section as a measure of the simulation’s effects. The simulation ends by asking the representative from the secretary of state’s office to review errors made by the groups and announce the amount in fines that each group must pay.

We completed an inductive analysis of the debrief comments and discerned three dominant themes: participants find the simulation’s disclosure requirements (1) incredibly burdensome, (2) potentially chilling on speech and association, and (3) utterly mystifying.

DEBRIEF RESULTS

In the years that we have implemented this simulation activity (we designed it in 2007), the debrief responses typically are consistent and unequivocal. We completed an inductive analysis of the debrief comments and discerned three dominant themes: participants find the simulation’s disclosure requirements (1) incredibly burdensome, (2) potentially chilling on speech and association, and (3) utterly mystifying. It is far different than the idealized campaign environment they learn about in typical classes as well as other campaign simulations that lack a campaign-finance element.

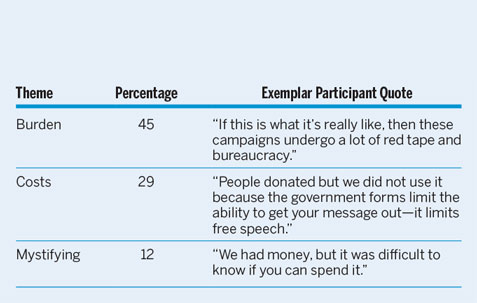

Table 1 indicates the percentage of comments per theme made during debriefs. Whereas burdens associated with the campaign-finance regulations clearly dominated the students’ comments, references to potential costs in the form of chilling speech and association also represented a non-trivial percentage of their observations. Although mentioned comparatively less often than the other themes, confusion and uncertainty associated with the disclosure laws emerged as a clear theme during the inductive coding of the comments. The percentages in the table do not total 100% because debrief discussions yielded comments that did not converge around identifiable themes. These comments included “I really liked this activity” and “The activity shows the benefits of contributions.” The substance of each of the three themes is briefly discussed in the following subsections.

Table 1 Percentage of Debrief Comments per Theme

Burdensome

During the first 30 minutes of the simulation, when groups plan their campaign, it is common to hear students talk about the beliefs and principles they want their campaign to convey and then turn to specific strategies for conveying those to potential voters. During the first day, that wish is translated into enthusiasm for creating campaign materials. In every iteration of this simulation, we observe that students genuinely enjoy generating political speech. However, we also consistently observe students switch quickly from the pleasure of exercising First Amendment rights to the pain of compliance. When the campaign-finance disclosure requirements are introduced, the initial plans often are significantly disrupted as participants grapple with the regulatory requirements. The most common response is for campaigns to dedicate one group member full time to disclosure requirements while the others continue with their original plans; however, they soon discover that one person often is not enough. “We dedicated several people just to do forms,” one student described.

Students often reflect on the burdens from the perspective of the average citizen. As one student commented, “It’s easy to make flyers and signs, but it’s hard to monitor your actions to avoid getting into trouble.” Or, as another described, “There are so many hoops to jump [through]—a regular person would not want to do it.” In fact, as the simulation proceeds, groups sometimes refuse to accept contributions. One campaign spokesperson noted, “When donations came in, we dreaded it. We eventually said we did not want them anymore because we had to constantly change our paperwork.” Every time we have implemented the simulation, at least one person makes an observation like this: “Money is important, but I can’t go through this manual and know what to do. I would need a lawyer and accountant on staff to make sure I did not make any mistakes.”

Chilling Speech and Association

During debriefs, simulation participants also commonly infer two effects from these burdens: a chill on speech and the reduced likelihood of political participation. For many, speech is reduced by refusing to accept contributions—even legal ones—which then limits the ability to speak through the production of campaign materials. As one participant described, “We rejected or returned contributions—they weren’t worth the hassle.” This sentiment is repeated in debriefs every time we run the simulation. A related effect occurs when groups intentionally hold back funds, thinking they will have to pay fines at the end of the simulation. In other words, rather than spending money on speaking, they wait to spend money on fines. As one participant described it, “You need to run a campaign by saving money for a legal defense.” We do not tell participants about the potential of being fined for mistakes; they often discover it on their own by reading the manual and then adjust their behavior spontaneously.

Just as students see implications for speech, they also see burdens on political involvement, particularly their own. “Having to fill out all of this stuff makes me never want to do this again” is a common refrain during debriefs. Some generalize the effects (“This dampens people’s willingness to participate”) whereas others personalize them (“If I knew this is what a campaign was like, I would be less likely to get involved”). Participants mostly ascribe reduced involvement to regulatory requirements, but others recognize the potential for campaign-finance laws to be used as a weapon, thereby creating a disincentive to be involved. As one astute participant discovered, “You can really use these laws to hurt the other side—watching their disclosed forms for mistakes to generate fines and even sabotaging them with illegal contributions.” Indeed, we have seen group members approach the secretary of state representative to report on the activities of other groups. This is a feature of the simulation that even mimics actual circumstances. When we wrote this article, for example, Colorado newspapers were reporting on how a local conservative political activist was using campaign-finance disclosure laws to bully opponents (Luning Reference Luning2017; Schrader Reference Schrader2017).

We always implement the debriefs before we ask our campaign-finance attorney to describe to the students the extent of their mistakes on the forms and the monetary consequences they would incur in the form of fines. Thus, all of the students’ comments are voiced before they fully understand the implications of campaign-finance disclosure systems. Every time we run the simulation, groups violate from five to 20 provisions of the law, generating fines ranging from a few thousand dollars to almost $100,000. The announcement of mistakes and fines typically is met with nervous laughter or an occasional pitiful defense such as, “But we’re just normal people.”

Utterly Mystifying

The fear of violating the law typically leads participants to spend significant time pouring over the campaign-finance manual when accepting a donation or making an expenditure while asking one another, “We did not get receipts for our expenditures; is that legal?” and “When did we get this money?” The requirements make them exceedingly wary about anything related to their campaign. When receiving donations as part of the simulation, it is common to hear students say, “Wait, …can we take this?” The same sentiments are expressed in the debriefs. One student observed, “It was difficult to figure out what we could and could not accept.” In fact, this type of observation is common for this theme, as one participant said, “It was painful to get a donation; we had to figure out if we could use it.”

CONCLUSION

Simulations are designed to help students develop a deeper and more concrete understanding of a particular topic, and comments from participants in our simulation suggest that it is achieving the desired ends. Through the activity, students learn that the requirements of a modern campaign are more complex than the idealized models that often are portrayed. They also understand more practically how money is the lifeblood of political speech and that it is a “two-edged sword.”

A potentially efficacious change to the activity would be to expand it beyond one class meeting and then measure its effects. A longer simulation would allow for the inclusion of a voter element such that hypothesized benefits of disclosure could be measured and discussed with students, particularly in relation to the types of costs discussed previously. It also could make possible original research to contribute additional findings to a current and important discussion/debate about disclosure requirements (Carpenter et al. Reference Carpenter, Primo, Tendetnik and Ho2014; Carpenter and Milyo 2012–Reference Carpenter and Milyo2013; Gilbert and Aiken Reference Gilbert and Aiken2015; Mayer Reference Mayer2014; Wood and Spencer Reference Wood and Spencer2016).

Finally, there is always a risk when programming simulations into the curriculum—we can never be certain until the first implementation whether students will find it engaging if not enjoyable. For those interested in using the simulation described herein, our observation has been that students are engaged throughout the activity and frequently express positive comments weeks later, when completing course evaluations. We expect that others who use this simulation will have a similar experience.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517002323