EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In light of concerns about sexual harassment within our profession, especially at the APSA Annual Meeting, the APSA Professional Ethics, Rights, and Freedoms Committee surveyed the entire APSA membership during February-March, 2017 to determine the extent and nature of perceived harassment experience. The results were intended to complement the recent institution of a new anti-harassment policy to find out what, if any, further courses of action might be warranted. Close-ended questions asked respondents to indicate their experience with specific types of treatment at the APSA Annual Meeting during a limited time frame: 2013–2016. Three open-ended questions elicited further detail. With a universe of 13,367 members contacted, we received 2,424 completed surveys, a response rate of 18.1%.

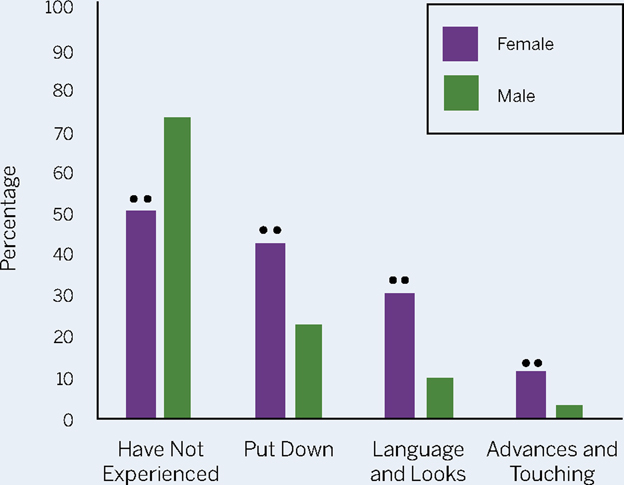

The topline results reveal that while most APSA members have not experienced harassing behavior at the Annual Meeting, a sizeable minority have, including a much higher percentage of women than men. About 63% of members, including 74% of men and 51% of women said they had never experienced any of the negative forms of behavior listed. We examined three broad categories of negative behavior. The first is feeling put down or experiencing condescension; 42% of women and 22% of men said this had happened to them. The second concerns inappropriate language or looks, such as experiencing offensive sexist remarks; getting stared at, leered, or ogled in a way that made them uncomfortable; or being exposed to sexist or suggestive materials which they found offensive. The results are that 30% of women and 10% of men report negative experiences in this regard. The third is inappropriate sexual advances or touching, such as unwanted attempts to establish a sexual relationship despite efforts to discourage it, being touched by someone in a way that was uncomfortable, or experiencing bribes or threats associated with sexual advances. About 11% of women and 3% of men reported these experiences.

Even in those cases where the percentage of members experiencing such incidents may be low, the number is nonetheless disconcerting. That 29 of our members felt they had experienced threats of professional retaliation for not being sexually cooperative, and 44 felt they were being bribed with special professional rewards is, respectively, 29 and 44 people too many.

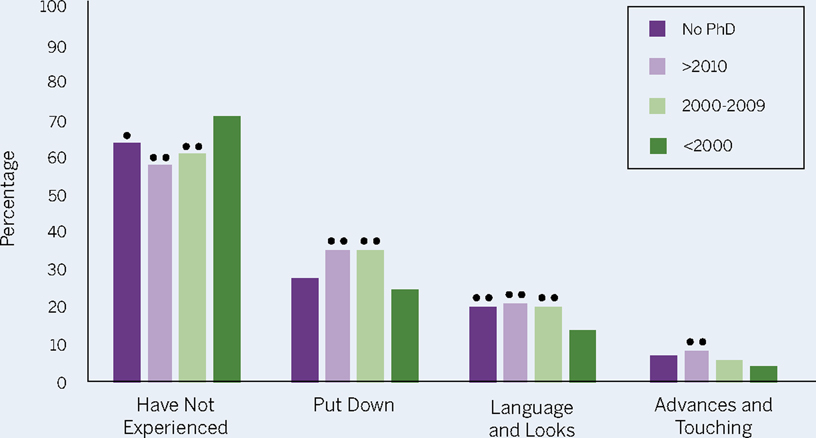

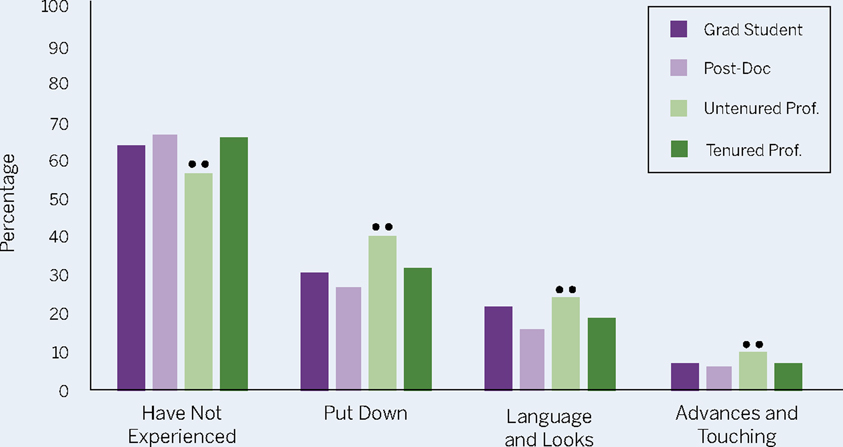

Further analysis reveals no differences across race/ethnicity categories. Colleagues from newer professional cohorts are more likely than more senior colleagues to say they have had experience with negative behavior. Likewise, untenured faculty experience more harassing and negative behavior than tenured faculty. Neither graduate students nor post-docs differ from senior faculty in these reports.

Multivariate analysis shows that gender, cohort, and meeting attendance predict negative conference experiences such that women and more recent PhD’s are subject to more negative and harassing behavior as are colleagues who attend meetings more frequently. These results vary somewhat depending on the type of negative behavior.

The responses to open-ended questions amplified and added rich detail to this quantitative analysis. They revealed five general categories of behavior colleagues described as examples of the negative experiences they had had:

-

(1) General disrespect, including being ignored or otherwise demeaned in ways that are not explicitly sexual;

-

(2) Referencing their gender, sexuality, or bodies in non-professional ways;

-

(3) Persistent or otherwise inappropriate romantic or sexual overtures;

-

(4) Discriminatory statements or attacks on one’s gender or sexuality;

-

(5) Harassing, demeaning, or discriminatory behavior based on categories other than gender; especially, race and prestige.

The abbreviated report published here provides more detail about the survey, and both the quantitative and qualitative analysis. The full report is available online at apsanet.org/reports. Footnote 1

INTRODUCTION: LEGAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Recent news events highlight the prevalence of sexual harassment in many professions. But not so long ago sexual harassment did not even have a name, and not until 1986 did the Supreme Court rule that sexual harassment is a violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Over time, the legal definition of sexual harassment has evolved. While at first the law recognized only quid pro quo harassment, involving specific threats or benefits, it now includes unwelcome sexual conduct that “has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, a hostile, or offensive working environment.” Increasingly, the notion of sexual harassment has been expanded to include gender harassment, or verbal or nonverbal behavior that is not explicitly about sexual relations, but which systematically demeans or insults people on the basis of their gender.

Thus, until very recently, the vast majority of senior members of our discipline, and certainly its leaders, were men who were unlikely to have been the targets of sexual or gender harassment and who had completed their professional socialization before there were many women in the discipline, and before sexual or gender harassment behavior was recognized as discrimination.

RAISING THE ISSUE OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT AT APSA ANNUAL MEETINGS

In 2015, eleven senior professors of political science from major universities addressed a letter to the APSA leadership and Professional Ethics, Rights, and Freedoms Committee (hereafter “the Committee”) expressing concern about sexual harassment in the political science discipline, saying that junior scholars and graduate students had often sought advice from them on how to deal with experiences of harassment at APSA meetings. A major roadblock to dealing with these experiences is that while the law covers places of employment, the Annual Meeting is not a place of employment, and therefore is not covered by the law unless the harassment occurs between people employed at the same institution.

The Committee immediately took up this matter as its major agenda for 2015–16.

At its February, 2016 meeting, the Committee concluded with the following action items:

-

1. It agreed that designated Ombudspersons should be available at the annual meeting (a) to assist individuals who encounter harassment or other such problems to help them in determining options for resolution and (b) to bring systemic concerns to the attention of the organization for resolution. This was implemented for the 2017 Annual Meeting.

-

2. It planned to propose to the APSA Council a new code of conduct designed to deter harassment at the annual meeting, and further proposed that the code be incorporated widely and noticeably into meetings-related communications. The code of conduct is available here: apsanet.org/divresources/policyprocedures.

-

3. It decided to undertake a survey of APSA members to gain more understanding of meeting participants’ sexual harassment experience.

APSA SURVEY ON SEXUAL HARASSMENT: METHOD AND RESPONSE

The purpose of the survey was simply to determine the extent of perceived harassment experience, along with basic information to help us understand who is most likely to experience harassment. After review of the literature the Survey Development Subcommittee concluded that the most appropriate model to use for the APSA survey is the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire developed by the Department of Defense (Fitzgerald, et al. Reference Fitzgerald, Magley, Drasgow and Waldo1999; Gutek, Murphy, and Douma Reference Gutek, Murphy and Douma2004). The survey focused on member experiences at Annual Meetings of the APSA over a limited four-year period of time: 2013–16, and asked them only about experiences they had had personally. The close-ended part of the questionnaire presented a list of specific negative behaviors to respondents and asked them whether they had ever experienced them, and if so, had they experienced them more than once. It then used three open-ended questions to allow respondents to offer examples and suggest solutions.

The anonymous survey was fielded in February and March, 2017. The “bounce-back” rate on the e-mail addresses was around 3%. Of the 13,367 members contacted, 2,810 started the survey and 2,424 completed it, yielding a response rate of 18.1%.

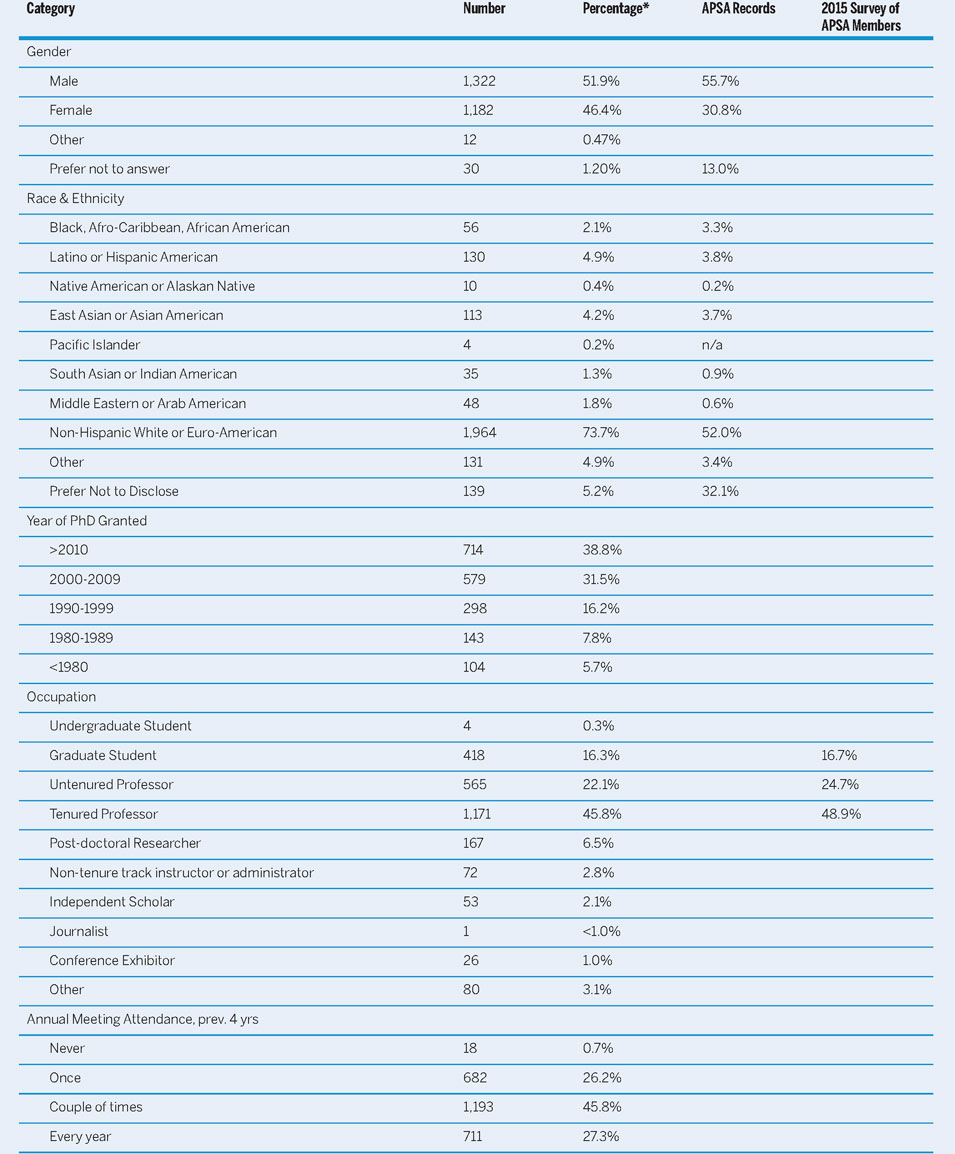

Comparison with APSA membership data shows that determining the representativeness of our response group is not straightforward because of non-response patterns in both APSA membership and survey data and our survey. Bearing that in mind, our survey respondents appear to over-represent women by about 16 percentage points and over-represent white people by about 21 percentage points (see table 1).

Table 1 APSA Harassment Survey Demographics

*APSA has multiple sources of data, described in the original report

*percentages do not add to 100% because respondents could select more than one category

REACTIONS TO THE HARASSMENT SURVEY

Because this survey was intended to address issues relating to the functioning of our profession, we found reactions to the project itself informative. Some made the effort to laud APSA for this initiative. Many commended APSA for doing the survey. Some defined it as a positive step for either seeking information about the situation at meetings or as a means for alerting the membership to the issues. Soon after launching the survey we received a letter from a woman who described going to her “first and last” APSA meeting when she was a post-doc to tell us why she thought this effort was important. Having completed her PhD at an elite institution, she was invited for drinks in the hotel bar by men who were “well-established in the field.” After she finished her drink she left the bar to go back to her room. The men continued to drink and, she later found, charged all their drinks to her room. She was afraid to confront them because of their stature, and learned a fellow post-doc had been threatened by a senior member of the field who said that if she said anything about such an experience, he would destroy her career.

Some were more critical. One colleague wrote approvingly of the “motives behind the survey,” but worried that it might be detrimental by implying “that the ‘victimization’ of adult members of the political science community by other members is a rampant and pressing problem, or that adults cannot normally discourage unwanted sexual advances on their own without serious negative professional repercussions,” and that it has implications that are “both demeaning and potentially disempowering for those it intends to help.” This respondent also worried that “such a survey, by its very nature, blurs the line between relatively innocent flirtation … and illegal harassment and assault, in ways that are more likely than not to generate misleading (and potentially alarmist) data.”

Some were more blunt in their critical responses, as in this example:

At first I thought this was a joke e-mail. Now I realize it is not. Let me spare you the tension: your ‘survey’ will show that APSA conferences are seething with sexual assault and sexual harassment, that 50% of our female members claim to have experienced one or the other, that they do not feel ‘safe’ during the conference, and APSA will respond to alarm and hysteria and calls for new controls, perhaps training for all attendees. And all of this will be false, totally false, akin to our current sham campus rape crisis. And those who see this as such will ignore it, and increasingly APSA itself.

Some comments were variations on this response: “Don’t make a big deal about what isn’t a systematic problem.” A few commented on question wording or other specific issues.

EXPERIENCES OF HARASSMENT: QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

The core of the survey asked, “At any APSA Annual Meeting you have attended in the past four years (2013–2016), has anyone attending the meeting ever done the following to you personally:

-

• Put you down or was condescending to you?

-

• Made offensive sexist remarks in your presence?

-

• Stared, leered, or ogled you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?

-

• Displayed, used, or distributed sexist or suggestive materials (for example, pictures, stories, or pornography) which you found offensive?

-

• Made unwanted attempts to establish a romantic sexual relationship with you despite your efforts to discourage it?

-

• Made you feel like you were being bribed with some sort of reward or special treatment to engage in sexual behavior?

-

• Made you feel threatened with some sort of retaliation for not being sexually cooperative (for example, by mentioning an upcoming review, grant, promotion, etc.)?

-

• Touched you in a way that made you feel uncomfortable?

Let us emphasize two aspects of the survey instrument before presenting the results:

First, the survey listed both experiences that constitute sexual harassment as traditionally understood and those that can constitute gender harassment. Second, the survey did not ask respondents whether they have experienced things of a sexual nature, but whether they had such experiences that they found offensive or made them uncomfortable, etc.

The majority of respondents report no personal experience with the offensive and demeaning behaviors the survey lists. About 63% of respondents say they had never experienced any of the listed negative behavior. In response to open-ended questions some said that they had experienced these negative behaviors, but before the four year time frame. Some said that as older women they were no longer subject to these problems, but had encountered them when they were younger.

Among those who indicated that they have experienced one or more forms of demeaning or offensive behavior, the largest percentage have experienced “put-downs” or condescending behavior. About 16% said they experienced put-downs only and another 15% said they had experienced put-downs and another form of negative behavior. About 5% said they had experienced only some form of negative behavior other than put-downs or condescension.

The topline results are enumerated in more detail in table 2. Almost one-third of respondents said they have experienced condescending or “put down” behavior, evenly divided between those who said it has happened once and those who say it has happened more than once. The other categories are smaller, some considerably so, but given how serious some of these charges are, we cannot feel relieved by the data. Consider that 29 colleagues say they were threatened with retaliation for not being sexually cooperative at a meeting, and the 44 who thought they were being bribed with some sort of reward or special treatment to engage in sexual behavior. Another 4%—108 people—feel that they have been sexually pursued at our professional meetings “despite … efforts to discourage it.” Although these represent small percentages of our membership, too many colleagues have had their experience of our professional conference marred by encountering seriously nasty behavior.

Table 2 Topline Results

As all previous literature suggests, women and other more vulnerable members of the profession—especially younger people and those without tenure—are more likely to report experiencing negative behavior from others. Figures 1–3 combine the specific listed behavior into three categories: put down, language and looks, and advances and touching. They analyze, respectively, gender, PhD cohort, and occupational differences. We do not show differences by race and ethnicity because that analysis revealed no differences in harassment reports. As expected, women are more likely than men to have experienced most of these forms of negative behavior, as are younger cohorts, and untenured professors. Although we expected graduate students and post-docs to stand out as well as compared with tenured faculty, they do not.

Figure 1 Annual Meeting Harassment by Gender

•• p < .05

Figure 2 Annual Meeting Harassment by PhD Year

• p < .10 •• p < .05 <2000 is baseline

Figure 3 Annual Meeting Harassment by Occupation

•• p < .05 Tenured Prof is baseline

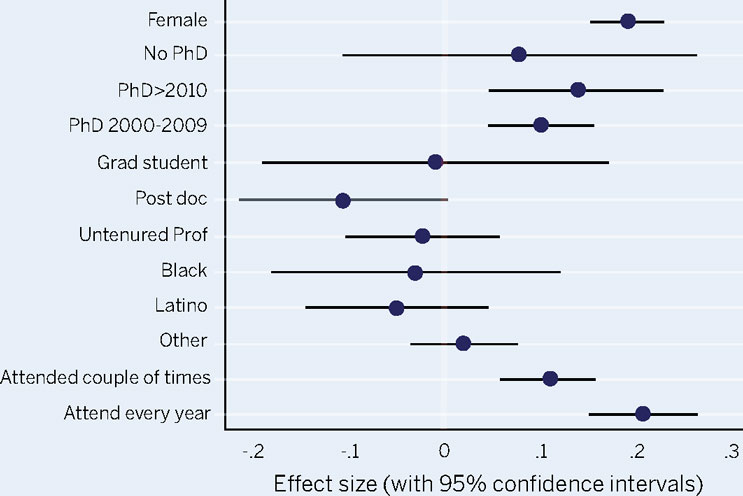

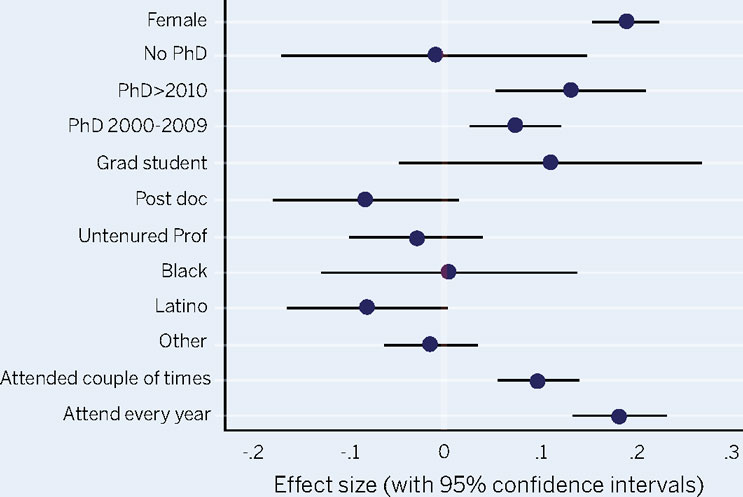

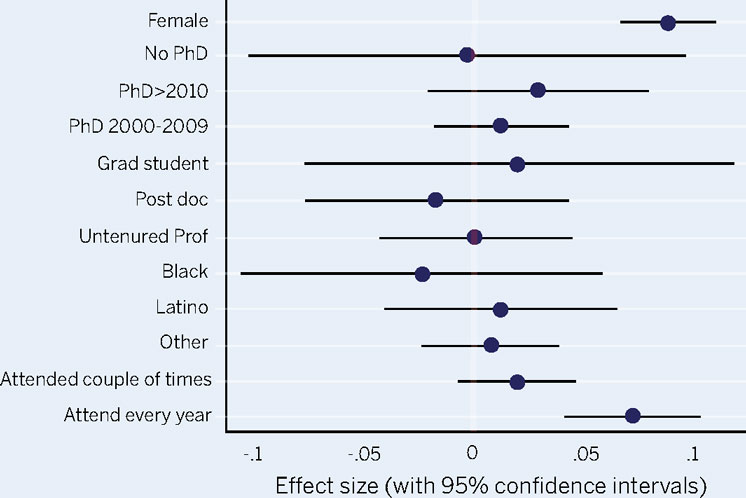

Finally we did multivariate (ordinary least squares) analysis to investigate the impact of gender, cohort, occupation, frequency of attendance, and race/ethnicity on experience of harassment (tables 3–tables 5). Footnote 2 In general, gender, cohort, and meeting attendance predict negative conference experiences such that women, more recent PhD’s, and colleagues who attend more regularly are subject to more negative and harassing behavior. We note that being untenured “falls out” of the picture in the multivariate analysis, presumably because age/cohort remains in. In the case of “advances and touching”—the clearest cast of sexual harassment in the most conventional sense, and the most egregious—only gender and regularly attending the APSA conference are significant predictors.

Table 3 Linear (OLS) Probability: Put Down

Table 4 Linear (OLS) Probability: Language and Looks

Table 5 Linear (OLS) Probability: Advances and Touching

EXAMPLES FROM THE OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

Responses to the open-ended questions add examples and texture to the quantitative survey results.

Comments by Respondents Who Had Not Personally Experienced Harassment

The majority of respondents had not themselves experienced any of the demeaning and objectionable behaviors listed in the survey and, not surprisingly, a large number of respondents reiterated this in the open-ended questions. As one person put it, and others implied or said in other words, “My experience is that males and females typically have normal conversations that include showing affection and friendship such as hugs, handshakes, laughing, touching, smiling... in other words, normal human interaction.” Indeed, the point is not whether people are socially comfortable with each other and engage in these acts of friendship and comradeship, but whether there are colleagues whose behavior is threatening, demeaning, or presumptuous and regardless of the perceptions and feelings of others, especially (but not only) systematically on the basis of gender.

At least 23 respondents—most of them men—explained that they had not had any of these experiences, but that they witnessed or heard from female graduate students and colleagues about experiences they had had. One respondent memorably put it:

I’m a straight, white, Christian male, who leans conservative on social issues and even I know the conference is a breeding ground for older men to behave inappropriately toward women, particularly younger women-grad students (sometimes their own students), postdocs, young professors. I have not seen much touching, but I have witnessed leering, sexist jokes made in the presence of women, inappropriate and gross comments about a woman’s appearance (in at least two cases this comment was made directly to or in front of the woman in question).

Some men reported on inappropriate behavior toward women that occurs out of the earshot of the particular woman concerned, for example: “Was present as a male professor inappropriately engaged a female graduate student. After she left, professor made sexually suggestive comments about following her up to her room. Was shocked.”

As we have seen, a few respondents said they had not experienced harassment, had not witnessed it, and thought it was a non-issue or merely a politicized concept.

People who themselves have not been subject to demeaning or harassing behavior differ in the degree to which they might be in the kind of situations where they would witness it or perceive it when it is happening. Women in particular are much less comfortable confiding in or seeking advice from some male advisors or colleagues about these matters, which will affect what these members of our profession are likely to hear.

Examples of Harassment

Many women and some men offered examples that help us understand the experiences to which the close-ended responses referred. In the vast majority of cases pronouns indicate that incidents of harassment were heterosexual, although some reported same-sex incidents. The examples—some hundred or so of them—fall into five general categories: (1) General disrespect, including being ignored or otherwise demeaned in ways that are not explicitly sexual; (2) Referencing their gender, sexuality, or bodies in non-professional ways; (3) Persistent or otherwise inappropriate romantic or sexual overtures; (4) Discriminatory statements or attacks on one’s gender or sexuality; (5) Harassing, demeaning, or discriminatory behavior based on categories other than gender; especially, race and prestige.

(1) General disrespect, including being ignored or otherwise demeaned in ways that are not explicitly sexual:

The most common complaint by women is that they find themselves ignored, dismissed, or not taken seriously at the meetings. Examples include noting when men on panels are introduced or referred to by their titles, while women are introduced or addressed using their first name. Often the feeling is a general sense of disrespect; as one person said, “The sexism I have experienced is generally more subtle, such as being ignored or talked over in group conversations.” Another reported, “It’s just a feeling in the room. Like when a man repeats exactly what I just said as if it were his own idea.” In some cases the dismissiveness explicitly concerns expertise:

I had a very senior male professor make a comment about what could a “girl” like me know about the topic. That’s really something since I was [in my 40s] at the time, and plenty knowledgeable about the topic. That bothers me more than the time a colleague was hitting on me.

Some women use a more traditional definition of sexual harassment, but describe their own experiences of gender harassment: “I haven’t personally felt this to be a problem. Condescension from male to female colleagues, sure. But sexually harassing behavior? No.”

(2) Referencing their gender, sexuality, or bodies in non-professional ways

The survey elicted a variety of examples. With regard to physical behavior, one woman reported,

At the annual meeting two years ago, I felt so ogled and stared at by older male attendees for wearing a dress instead of a pantsuit one morning that I went all the way back to my hotel room to change because I was made to feel so uncomfortable for wearing a professional dress. It was distressing, upsetting, inconvenient and disappointing.

Many women reported on comments they found inappropriate:

My attire and physique was commented on by an older male academic after a panel on which I was a presenter.

A few women referenced the annoyance of having men “staring at our chests when they’re talking to us.”

One respondent suggested how such inappropriate gender-referencing can frame apparently professional interactions.

I got my first job by doing interviews at the APSA meeting back in the late 1980s. I cannot tell you how many times I was asked if I could teach a course on women even though nothing on my cv indicates that I’m trained in that field. It was so insulting that I started cutting interviews short if that question was asked.

Indeed there is no reason to ask women to teach women and politics, or African Americans to teach race politics, or gay people to teach sexual politics if nothing in their CV suggests they are trained, expert, or professionally interested in that field of inquiry.

(3) Persistent or otherwise inappropriate romantic or sexual overtures

Institutional sexual harassment policies explicitly warn staff and faculty about initiating sexual or romantic relationships across status and supervisory lines, but it seems that some colleagues think these norms do not apply away from home at professional meetings.

I am personally aware of an incident that happened at [a recent APSA meeting] in which a senior male professor ... sexually harassed a female PhD student. The professor suggested [to] the student they should talk about her research “after hours,” which involved leaving the conference hotel at night with him for a drink and then walking outside together (alone), and finally him making an unwanted advance on her. All of this was done under the ostensible premise of providing feedback on the student’s paper and helping her prep for the job market…. Not only did this situation put the student in a compromised position, but it also traps her in that her refusing the advancements of someone who is very senior and likely to be influential in recommending her candidacy (let alone sit on a search committee) may result in him actively damaging her career prospects.

On several occasions, I have experienced mostly male colleagues treat the Annual Meeting (and other PS conferences) like their personal playground and the women who attend it—including graduate students—as their weekend dating pool. A prominent scholar in the discipline, for example, texted a grad student in the department where he was on faculty and told her to bring her “hot friends” to the bar he was at.

Although the survey asked only about overtures that persisted despite being rejected, making sexual or romantic overtures in a business setting can interfere with professional relations, which is all the more serious if it is in the context of unequal professional status:

A senior scholar made physical sexual advances after walking me back to my hotel after a group dinner. I declined. It was not made explicit that I would face professional penalization for declining, but our working relationship has not been the same since.

Our data suggest that young women are especially subject to this experience. As one wrote,

I’m not comfortable talking about specific instances, but I will say that being a young woman scholar at APSA is often exhausting. The harassment is nearly constant, from men who stare at your chest rather than your eyes while you’re speaking to explicit propositioning after a few drinks at a reception, with the strong implication that saying “yes” will lead to career opportunities.

Professional political scientists are not the only people at the meetings who are implicated in the dynamics of sexual and gender harassment. Two book exhibitors who responded to the survey discussed the discomfort of being “trapped” in their booths, having to be polite to potential consumers or authors, but suffering inappropriate and persistent attention. As one put it, “I get the impression that there are some people who believe that women who work in the exhibition room are ‘open for business.’ There have been times I was more or less trapped in my booth (which I basically cannot leave) by someone who insisted on talking me up.”

(4) Discriminatory statements or attacks on one’s gender or sexuality

A few men reported that they experienced explicit discrimination on the basis of their gender, often in combination with their race or ideology. For example, one wrote,

Numerous panels and private discussions have belittled white males and portrayed them as inherently inferior, by nature oppressive, and determined to do ill to all others. The vitriol, the smugness, and the assumed status of victimhood made me extremely uncomfortable, as did the clear looks of disapproval, the open hostility to my point of view, and the determination to see to it that my arguments would not be heard. This hostile atmosphere is pervasive at APSA events.

(5) Harassing, demeaning, or discriminatory behavior based on categories other than gender; especially, race, and prestige.

Although this survey was framed as a study of sexual harassment, a few respondents took the opportunity to point to other bases for discrimination and harassment, and gave examples. In a few cases, colleagues believe that there is a strong political bias, especially toward the left, which impedes scholarly discourse or excludes particular individuals:

Most folks are very professional. However, each panel has one or two individuals that are so politically biased (usually left of center) that they are unprofessional and no one can take their papers seriously.

Others pointed to instances of race bias or homophobia:

I have been in a number of situations where colleagues made misogynistic and homophobic comments. The latter stand out in particular, since those colleagues assumed I was heterosexual.

Other responses underscored the specific impact of being an African American woman at the conference; some colleagues reported that hotel security where the conference was being held accused some African American women colleagues of being prostitutes. As one respondent said, “Coaching hotel security to not question the presence of black women in business suits during the convention would be a long way towards making the conference more inclusive to them.” Others reported on a lack of respect they encounter from colleagues who are dismissive of people who study gender or sexuality and politics.

Some respondents complained about a status system in which the prestige of one’s institution, or personal prestige determines how people are treated, what some people called the “nametag effect.”

Causes of and Solutions to Harassment and Demeaning Behavior

Most respondents merely described incidents they experienced or witnessed and did not speculate on the reasons why people engage in these behaviors toward colleagues at political science meetings. Others suggested reasons for such behavior, often perceiving the problem as a generational issue and cultural lag. Others define it simply as ignorance and lack of awareness. For example,

Some men in the profession may not be aware that being in a position of power and making advances puts untenured women in an uncomfortable situation where while they still say no, they can’t say so as strongly or with as much emphasis as they would outside of a professional context. Making men aware of this could be helpful.

For women who encounter these situations, it can be a disheartening recognition of some of the roadblocks not just to women’s professional success, but their ability to enjoy professional settings in ordinary ways:

Though I did say that I had experienced unwanted sexual advances, I don’t think it rose to the level of sexual harassment but rather was more of a misunderstanding. It certainly wasn’t anything that merited a formal complaint. Nonetheless, it’s quite disheartening to realize that while *I* thought I was successfully networking, the person I saw as a new professional contact did not see me primarily as a fellow scholar but rather as a potential hookup.

In response to the question of whether there is anything that can be done to make the meetings more inclusive and welcoming, many respondents said that it is important to broadcast the APSA anti-harassment policy more widely. Many also called for clear means for reporting violators of the policy, and for investigation and enforcement, an issue tackled by an APSA special committee in 2017. Others were less sure there is a solution. As one person responded,

No. I don’t think the people I’ve seen engage in this behavior are aware of or would be willing to acknowledge it as problematic. And I imagine any ‘education’ around it would fall on deaf ears, and that these people would assume the problem was someone else.

Some men and women wondered whether they could do more to alleviate the problem by intervening more as bystanders. Some said they weren’t sure what they should do: “I observed a tenured professor speak to and touch a female graduate student in an extremely inappropriate fashion at an APSA dinner. It was extremely uncomfortable, and it was unclear whether I should intervene.”

One respondent showed what difference a bystander can make. A young woman reported,

What I experienced is a “normal” act of micro-aggression of being spoken down to, as though I were still a graduate student. A male member of the audience came up to me and asked whether he had just witnessed an act of sexism, calling my attention to how I had been dismissed and lectured to, as though a student. Of course I had noticed this myself, but I felt affirmed in having a senior male colleague corroborate this. The panel member in question is very senior and famous, and this incident is typical of what I have experienced throughout my career. I wish more attention would be drawn to this so that possibly more male colleagues would exhibit the awareness that I experienced after this panel concluded.

Although it should not be necessary for women to receive corroboration from men to deal with these challenges, when men speak up about witnessing harassment, the alliance against demeaning behavior is very helpful, especially for younger colleagues who see harassment as an added burden to the normal issues of making one’s way in the profession. Many campuses are now offering bystander education and workshops, to help people think about ways they can make a difference when they witness harassment.

A persistent theme concerned the negative impact of the gender imbalance of participation in the meetings and on panels, and the importance of addressing that imbalance. Women discussed the challenges posed by being the only woman on a panel, a point underscored by research on the impact of the group’s gender balance on communication and behavior within those groups. (e.g., Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Kabat-Farr and Cortina Reference Kabat-Farr and Cortina2014). Consider this comment.

I was the only woman on a panel of very distinguished men and the chair, a former APSA President, made a disparaging remark about my research and its relevance. As a junior professor, I was mortified and intimidated.

We cannot know from this comment whether there was any gender-based motivation or manifest content to the reaction to this colleague’s paper. But research suggests that being the only woman on such a panel, and being junior at that, is very likely to lead to the reaction this colleague had.

Of course problems can arise from “misunderstandings” over the nature of a social interaction, but some misunderstandings can derive from gender-based assumptions about what it means when women act in a proactively friendly way toward men:

I think that “conference culture” in general can be more complicated for women to negotiate. Most of us are trying to be polite (especially junior scholars and those on the job market), but this politeness sometimes seems to be an open invitation for male colleagues to assume that we’re interested or that a smile is some kind of a come-on. This is an especially problematic dynamic when it comes to networking with strangers: on more than one occasion, I have sought to engage a man in a professional conversation, only to have him assume that I was trying to hit on him. Weird, right? Would a man assume that another man at the conference was trying to hit on him? I remember waiting in a very long line to get coffee … and having what I thought was a pleasant, professional conversation with the man standing next to me. Later that night, I found numerous phone messages in my hotel room from him, inviting me for a drink. Apparently, he had simply seen my name on my name-tag and called the conference hotel to leave a message. There’s nothing “wrong” with this on its face; it’s just creepy. I very frequently get the signal at APSA that men can easily initiate networking with men and with women, but that when women try to network with men, it gets misinterpreted.

A couple of men indicated that they had experiences of women who used their sexuality for professional advancement. As one said,

As a quite successful man with lots of “informal power” in the profession I have many times been approached by younger un-tenured female colleagues (and also by female PhD students) at APSA meetings with not so subtle invitations to intimate encounters. After a number of such experiences, it became very obvious to me that what they were interested in was not me but the emotional and professional support (advice, access to networks, etc.) I could give them for advancing their careers. Every time, this had ended badly and with lots of sadness, both for me and for them.

One especially worrying situation that some responses underscored is the discomfort women experience when senior faculty use their hotel room to interview candidates for jobs, and suggest that people should be counseled against this. The reasons should be obvious.

Conclusions

The results of this survey gives us little reason for either extraordinary alarm or celebration about the presence of harassment at American Political Science Association annual meetings. The majority of respondents had not experienced or witnessed instances of harassment or demeaning behavior as we enumerated them. But a large number of colleagues, and an especially large number of women, have had unfortunate experiences.

There is no acceptable amount of sexual harassment other than none. That 128 of our colleagues reported experiencing unwanted sexual advances despite rejecting them, threats or bribes, or inappropriate touching in just the past four years in what is, after all, a professional setting, says we must give careful thought both about how to reduce and eliminate that number and also how to support those colleagues who have had these experiences. The multivariate analysis shows that two things—gender and how often one goes to meetings—are predictors of these forms of harassment. No women should learn the lesson that not attending the Annual Meeting is an effective means of avoiding harassment.

That such a large number of our colleagues—30% of women who responded to the survey—have encountered situations in which by language or nonverbal behavior colleagues in this professional setting have made sexist comments or called inappropriate attention to their gender, sexuality, or bodies also warrants careful thought to how to reduce that number and also how to support those colleagues who have had these experiences. For some women it is just part of the atmosphere, rather than some specific event:

I don’t have a particular event in mind but I cannot in good conscience say that I have not heard sexist remarks at APSA because they are so ubiquitous. Let me put this another way: I would not be surprised in the least to hear at least some sexist remark while in the company of men at a professional meeting.

Our youngest colleagues, women, and those who attend meetings more regularly are more likely to have these experiences. Some older women reflected that these things used to happen to them when they were younger, but don’t any more. Harassment should not be a hazing experience for our newest colleagues.

We are struck by the very large number of colleagues of both sexes who have had occasion to feel put down or experience condescension by others. This suggests a broader issue about professional communication. The Twitterverse of political scientists often jokes about “Reviewer #2,” the one who seems to regard professional reviewing as self-inflating combat. No doubt Reviewer #2 participates in APSA Annual Meetings. As one respondent put it, perhaps only partly jokingly. “It’s an academic conference. People are condescending towards me ALL THE TIME. I thought that was the POINT of academic conferences.” Or, as one man put it: “Asking if someone at APSA was ever condescending to me is like asking if the sky is blue.” Perhaps session chairs and other bystanders can assist with encouraging a more civil and productive—even if rigorous and intellectually sharp—tone.

It can be difficult to distinguish put downs and condescension that are gender-based (or based on any other specific demographic category) from those that are not.

But in the context of the great gender imbalance that remains in our senior ranks, in many parts of our profession, and that still describes many conference panels, women have good reason to suspect they have been subjected to gender-based belittling even when gender is not explicitly referenced, because research indicates that gender balance helps determine how women are treated.

One of the most prominent recent efforts to highlight women’s contributions to our discipline and to encourage people to pay attention to and use their work is #womenalsoknowstuff, which lists on its website (womenalsoknowstuff.com) nearly 2,000 women experts in political science and provides details people can use to learn more about their work, cite them, and include their work in syllabi. Its active Twitter presence as @womenalsoknow helped to spawn @pocalsoknow and @womenknowhistory.

People who perpetrate sexual and gender harassment can be unaware of the implications and impacts of their actions. The fact that women receive more disruptive questioning in finalist job talks (Blair-Loy, et al. Reference Blair-Loy, Rogers, Glaser, Anne Wong, Abraham and Cosmn2017) is not likely noticed by those doing the questioning; they probably see themselves as asking particular individuals appropriate questions. Young women who have the uncomfortable—but common—experience of men “talking to their chests” rather than their faces tend to understand that the men who are doing this are probably unaware that they are doing it, or that the women see where their eyes are pointed. People who tell sexist jokes just think they are funny, and don’t understand that, especially when women are a small minority of those present, these jokes make many of them very uncomfortable. For women who use the annual meetings as a time to focus on their careers scholarship, make professional contacts, and even spend time with professional friends, this attention to their gender is especially distracting, frustrating, and even hurtful.

Political science is not alone, as recent news has made clear. A recent widely-circulated paper did a linguistic analysis of the Economics Job Market Rumors website, and found telling and disturbing differences in the words used to describe and refer to women and men (Wu Reference Wu2017). Men and women alike have commented on the demeaning qualities of the Political Science Job Rumor website, and the recent invention of #PSMinfo is intended in part to provide a better source of information.

It is not surprising that the cultural change in the profession has left some colleagues uncomfortable with the changes. Some are left uncertain about how to interact in normal, social, and professional ways with women. Some feel personally attacked and demeaned by discussions such as these. Some feel that discussing these issues or creating policies about harassment makes it more difficult to engage in appropriate professional relations:

Stop making it impossible for people to have normal male-female interaction without having to worry if casual conversation constitutes “harassment.”

For some respondents, the solution is not policies, but women developing the right skills to handle problems they encounter.

We know of no evidence suggesting that such policies have a negative impact on work quality, professional opportunity, or social or professional relations in the workplace and there is considerable evidence that sexual and gender harassment have negative impacts. Nevertheless, change requires listening across the discipline.

Our reading of the surveys and of the open-ended responses suggests that most women, at least those who responded, and said they have experienced sexual or gender harassment, just want to be treated like professional colleagues. As one respondent said, “Basic etiquette should prevent bad behavior.” But given that it doesn’t in a significant minority of cases, the new APSA policies and the presence of Ombuds at our meetings aim to support an atmosphere at our annual meetings where all should expect to be treated in appropriate professional ways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Betsy Super and Amanda Meyers of the APSA for their assistance. We also express our appreciation to Andre Audette, who gave us invaluable help.