Finding ways to promote government transparency (national, regional, and local) is a serious issue among academics, policy makers, and citizens concerned about a perceived decline in the quality of governance in long-standing democracies (Cucciniello, Porumbescu, and Grimmelikhuijsen Reference Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen2017). Many scholars have highlighted transparency as a key feature of good governance as a means to reduce corruption and its costs to the public(Weller Reference Weller, Samek, Montavon, Vedaldi, Hansen and Müller2019; Cahlikova and Mabillard Reference Cahlikova and Mabillard2020; Matheus, Janssen, and Maheshwari Reference Matheus, Janssen and Maheshwari2020). At the local level, it has been argued that greater transparency in local government decision making, which provides citizens with access to information about how and why decisions were reached, is related to higher levels of trust and engagement among citizens (Harrison and Sayogo Reference Harrison and Sayogo2014). These concerns about transparency were magnified during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially at the local level, where access to information about resources, the latest public health guidance, and how authorities were spending pandemic resources was a public priority (Maher, Hoang, and Hindery Reference Maher, Hoang and Hindery2020). Thus, identifying the important determinants of transparency (and its absence) has been of even more critical interest to local-government scholars since 2020.

We are interested in one aspect of the transparency debate because it has become relevant in more countries in Europe: the challenge presented to long-standing national parties by non-partisan independent local lists (ILLs) and non-partisan mayors. We selected Portugal for our case study, where there has been a slow but steady increase in municipalities being governed by non-partisan mayors (who topped non-partisan lists) in local elections to the municipal council (câmara municipal) since 2006. According to Jalali (Reference Jalali2014, 239), “The câmara municipal is the executive body, albeit a hybrid one. It is…composed of a mayor and councilors….The mayor is the chief executive, with a wide-ranging set of powers.” These mayors were all once elected from national political party lists, but since the adoption of law 1/2001, “…the monopoly of political representation that parties had at the municipal level was revoked” (Jalali Reference Jalali2014, 241). ILLs were allowed to present and compete (they still are not allowed in national contests) and have eroded the vote totals for the two largest parties since then.

The dominant national parties in Portugal (i.e., the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party) also were impacted at the local level by the adoption of a 2005 law that mandated a three-term limit for mayors. This led to tremendous turnover by 2013, when the full effects of the law were applied: 52% of incumbent mayors were not eligible to run again in that election, which opened the door for challenges from new lists and citizens’ groups (Veiga et al. Reference Veiga, Veiga, Fernandes and Martins2017). Since 2013, the number of non-partisan mayors has increased from six to 13 to 17 and, after the last elections, to 19.

Despite widespread acknowledgment of an increase in ILLs in Europe, there is little empirical research that examines the potential impact of this phenomenon on recent efforts to promote greater transparency in local-government decision making. Will the increase in number of councils governed by independents make a difference? Are the levels of local transparency in councils governed by party mayors and by non-party mayors significantly different or not? This exploratory study begins to fill that gap. The questions are important to answer as more and more countries contemplate changes to their local (as well as regional and national) electoral rules to allow for more ILLs to compete and win seats—usually in the name of improving the quality of democracy (as in Portugal in 2005). This article is a starting point, given that it focuses on only a single country over a subset of years. However, the study further develops avenues of future research—from a greater number of countries, over longer periods—given the increase of non-partisan mayors in local governance. To reiterate, our central aim is to understand what difference, if any, the municipal council executive “independence” might have on local-government transparency efforts. The study discusses the conflicting theoretical expectations about partisan affiliation and transparency, based on a brief review of earlier work. We then introduce our methodology and the source of our data on municipal transparency in Portugal, present our results, and conclude with avenues for further exploration.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Although many important political determinants of local government transparency have been explored in the literature, we examined whether party-affiliated councils behave differently than independently led councils with regard to transparency (Egner et al. Reference Egner, Gendźwiłł, Swianiewicz, Pleschberger, Heinelt, Magnier, Cabria and Reynaert2018). As the famed democratic theorist Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1942, 1) once noted, “Political parties created democracy and modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.” Even for would-be local leaders, partisan affiliation serves a number of important functions. Among others, it is a means of signalling to voters that candidates are supported by a national party, have values consistent with that party, and both the candidate and the community may benefit from a partisan connection with national or regional party sponsors—especially if the partisan composition of the local government is aligned with that of the higher level of government (Borrella-Mas and Rode Reference Borrella-Mas and Rode2021).

Furthermore, parties do the work of recruiting, training, and financially supporting local politicians, as well as providing short cuts (i.e., cues) to voters about likely policy preferences and priorities. In part, a partisan executive’s commitment to local transparency could be explained by national parties having clear incentives to police their own candidates for the sake of the party, by winnowing out corrupt and ineffective types and promoting more effective candidates (Borrella-Mas and Rode Reference Borrella-Mas and Rode2021). One example stems from a Portuguese case in the municipality of Oeiras, the tenth-largest municipality in the country, which had been headed since 1985 by Isaltino Morais. “As a result of a legal prosecution for fraud and corruption, Isaltino Morais was not selected as the mayoral candidate of the PSD in the run-up to the 2005 local elections” (Jalali Reference Jalali2014, 248). Although the party did its job by refusing to nominate Morais (who later was imprisoned), it is ironic that Morais subsequently formed an “independent” list and won.

It nevertheless is possible that the amount of coordination, organization, and commitment typically displayed by political partisans (Ypi Reference Ypi2016) may influence their elected “agents” and act as institutional “tethers” to their behavior in ways that favor local transparency efforts. Moreover, political parties often are studied as drivers of local-government transparency efforts (Araújo and Tejedo-Romero Reference Araújo and Tejedo-Romero2016; Brás and Dowley Reference Brás and Dowley2021; del Sol Reference del Sol2013).

However, not everyone is convinced that party-affiliated local governments are more transparent, and there has been a popular movement to delink local, municipal-level elections from partisan competition. For instance, “partisanship can bias voters’ perceptions and weaken local accountability” (Breux and Couture Reference Breux and Couture2018, 24). Part of the impetus for even allowing “independent” lists to organize and compete may be to challenge parties that perhaps have become complacent and nonresponsive to citizens’ desire for more transparency, less corruption, and less-opaque decision making. Thus, some scholars have suggested that independently led governments are more responsive to voters and local issues; others suggest that non-partisan mayors may be better municipal managers and pragmatic problem solvers. In fact, non-partisan local lists usually are to “a large extent locally based and, insofar as they formulate political programmes, these very often revolve around local issues” (Aars and Ringkjøb Reference Aars and Ringkjøb2005, 162). In addition, unlike other formal elective acts, local elections usually are delinked from ideology and closer to important quotidian issues of local community life (Lucas, McGregor, and Bridgman Reference Lucas, McGregor and Bridgman2023), such as facilities maintenance, speed limits, and parking permits.

In several European countries, the number of non-partisan mayors (linked to independent or non-partisan groups) has been growing (Gendźwiłł Reference Gendźwiłł2017). Some scholars have suggested that democracy in the local context is now in a process of change in Europe, with mayors becoming more neutral and making non-ideological decisions even when they belong to a political party (Kukovic et al. Reference Kukovic, Copus, Hacek and Blair2015).

Because this is becoming more common at the local level in some European countries, “the greater the extent to which municipal production is ‘freed from politics,’ the greater the questioning of the role of the parties as aggregating and integrating institutions may become” (Wise and Amnå Reference Wise and Amnå1993, 356). In fact, political parties are losing ground at the local level (Vampa Reference Vampa2016) and extremely low levels of party membership are found in local governments in some countries (e.g., Poland and Slovenia) (Gendźwiłł and Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2014; Haček Reference Haček2023). Institutional changes in local governments have taken place in Germany that reduced parties’ relevance through reforms aligned to a citizen-oriented model of democracy (Vetter Reference Vetter2009). In this vein, Vampa (Reference Vampa2016) suggested that local government is no longer merely a competition space between political parties but instead has been filled by independent leaders (from independent or non-partisan groups) who have the advantage of being closer to citizens’ demands and capturing a larger share of personal votes.

In the context of a closer relationship between non-partisan mayors and citizens, less politicized environments seem to favor online open governments and, therefore, their local transparency (Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney2017). The candidacy and election of a non-partisan member may help local people to feel that they can exercise their right to local self-government in their own municipality (Kukovic and Hacek Reference Kukovic and Hacek2011) and to be accountable to local inhabitants rather to central party leaders (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2021). Although only a small proportion of mayors in European democracies are non-partisan (Egner, Sweeting, and Klok Reference Egner, Sweeting, Klok, Egner, Sweeting and Klok2013), Gendźwiłł and Żółtak (Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2014) suggested that they may be more accountable and transparent.

Of course, we must acknowledge—as others before us have—that in Portugal, non-partisan mayors often are former partisans themselves or even part of a formally non-partisan movement with party support. Some citizens even refer to them as fake or false independents who simply fell out or lost the support of their own party. Nonetheless, they often campaign on promises to be more transparent and less corrupt than the long-standing party-affiliated elite. However, even with former links to and support from existing parties, non-party movements stood for election as independent local groups. Most notable in the Portuguese context is Rui Moreira, the independent mayor of Porto—Portugal’s second-largest city. He ran on a decidedly anti-party platform, in which he that noted the “apparatchiks” of parties of the left and the right now are associated with economic mismanagement and corruption; he also touted his business credentials (Minder Reference Minder2013). He went on to win two additional terms.

The increase in number of independently governed municipalities allows us to make preliminary comparisons regarding their efforts to govern transparently, compared to their partisan peers, and contribute through exploratory research to the continuing debate among scholars about the impact of partisan independence on local-government transparency.

METHODS

This section describes the methodological approach by outlining the key steps and specific options for conducting the research.

Variables and Research Design

This exploratory study examines whether the transparency levels in municipalities governed by non-partisan groups are significantly different from those governed by political parties. To this end, secondary data were collected from the following sources between 2013 and 2017 (the last year available): Transparency International’s Municipal Transparency Index (MTI) in Portugal and the Portuguese National Elections Commission. Based on panel data, the empirical analysis included all of Portugal’s 308 municipalities.

This exploratory study examines whether the transparency levels in municipalities governed by non-partisan groups are significantly different from those governed by political parties.

The MTI is an indexFootnote 1 developed by da Cruz et al. (Reference da Cruz, Tavares, Marques, Jorge and de Sousa2016) in conjunction with Transparency International that measured the efforts of local governments in Portugal to provide transparent governance. Operationally, transparency in this context means “the publicity of all the acts of government and their representatives to provide civil society with relevant information in a complete, timely, and accessible manner” (i.e., on the municipalities’ official websites) (da Cruz et al. Reference da Cruz, Tavares, Marques, Jorge and de Sousa2016, 872). The index was evaluated along seven dimensions of public availability/access to information corresponding to the following weights:

-

(1) “Organizational information, social composition, and operation of the municipality (executive and deliberative bodies)” [15% of the MTI]

-

(2) “Plans and planning” [6% of the MTI]

-

(3) “Local taxes, rates, service charges, and regulations” [12% of the MTI]

-

(4) “Relationship with citizens as customers” [6% of the MTI]

-

(5) “Public procurement” [21% of the MTI]

-

(6) “Economic and financial transparency” [15% of the MTI]

-

(7) ”Urban planning and land use management” [25% of the MTI]

Regarding the local-government variable, all municipalities governed by political parties take the value 1, whereas municipalities governed by independent (non-partisan) groups take the value 0. This political party (PP) dummy variable was not invariant over time; more specifically, we considered the results of the municipal elections of October 11, 2009. These results reflected the values of the dummy variables in 2013, as well as those of the municipal elections held on September 29, 2013, in which the values of the dummy variable affected 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017. These data were collated by the Portuguese National Elections Commission.

Data

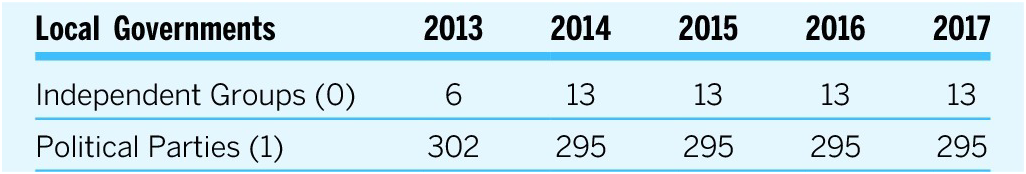

Table 1 presents information about the asymmetrical number of municipalities governed by political parties and by independent (non-partisan) groups in Portugal. The 13 municipalities and their mayors are as follows: Anadia (Maria Cardoso), Aguiar da Beira (Joaquim Bonifácio), Borba (António Anselmo), Estremoz (Luís Mourinha), Redondo (António Recto), Oeiras (Paulo Vistas), Portalegre (Adelaide Teixeira), Matosinhos (Guilherme Pinto), Porto (Rui Moreira), Vila Nova de Cerveira (João Nogueira), Santa Cruz (Filipe Sousa), São Vicente (José Garcês), and Calheta [Açores] (Décio Pereira). From the 2013 election, regarding non-partisan mayors (i.e., a total of six from the previous election), four left the local government, two were reelected, and 11 were elected for the first time. Overall, it is a set of heterogeneous municipalities: from the countryside to the seaside; from Porto, the second-largest city in Portugal, to tiny Vila Nova de Cerveira; and from Portuguese archipelagos (Santa Cruz, São Vicente, and Calheta) to inland municipalities in continental Portugal.

Table 1 Distribution of Local Governments

Hierarchical Bayesian models provide a way to model and account for the inherent variation and heterogeneity in the data, allowing for more robust parameter estimation and inference—particularly when dealing with groups of varying sizes (see Johndrow et al. Reference Johndrow, Smith, Pillai and Dunson2019).

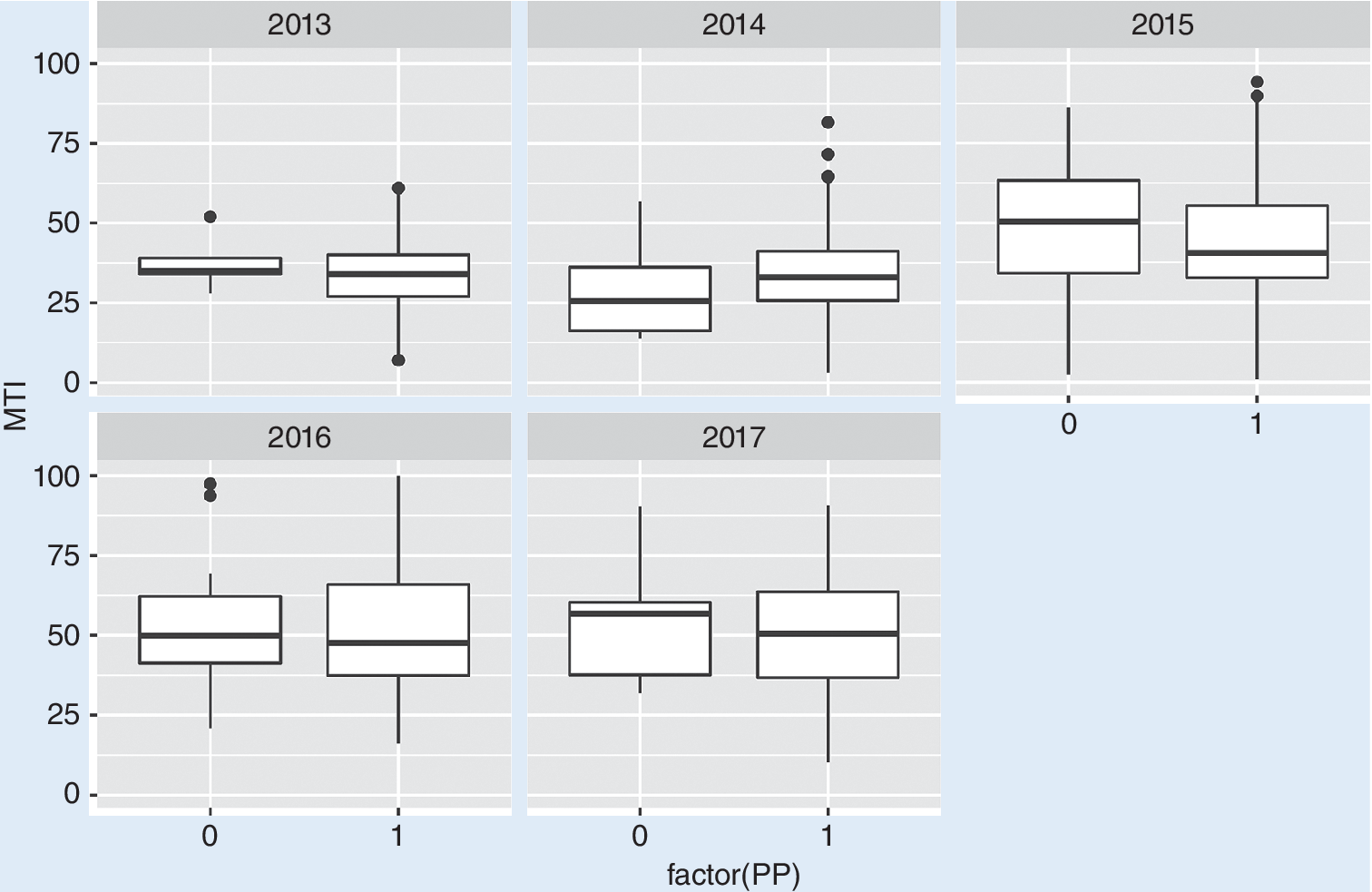

Regarding the descriptive statistics of the two groups of local government, the box plots in Figure 1 display the minimum, the maximum, the median, and the first and the third quartiles.

Figure 1 Box Plot of MTI (1-Political Parties versus 0-Independent Groups)

Briefly, the MTI of the two groups of local government does not show a different pattern for dispersion or central tendency. Nevertheless, an upward trend in MTI can be decoded over a period of five years, as confirmed by Figure 2.

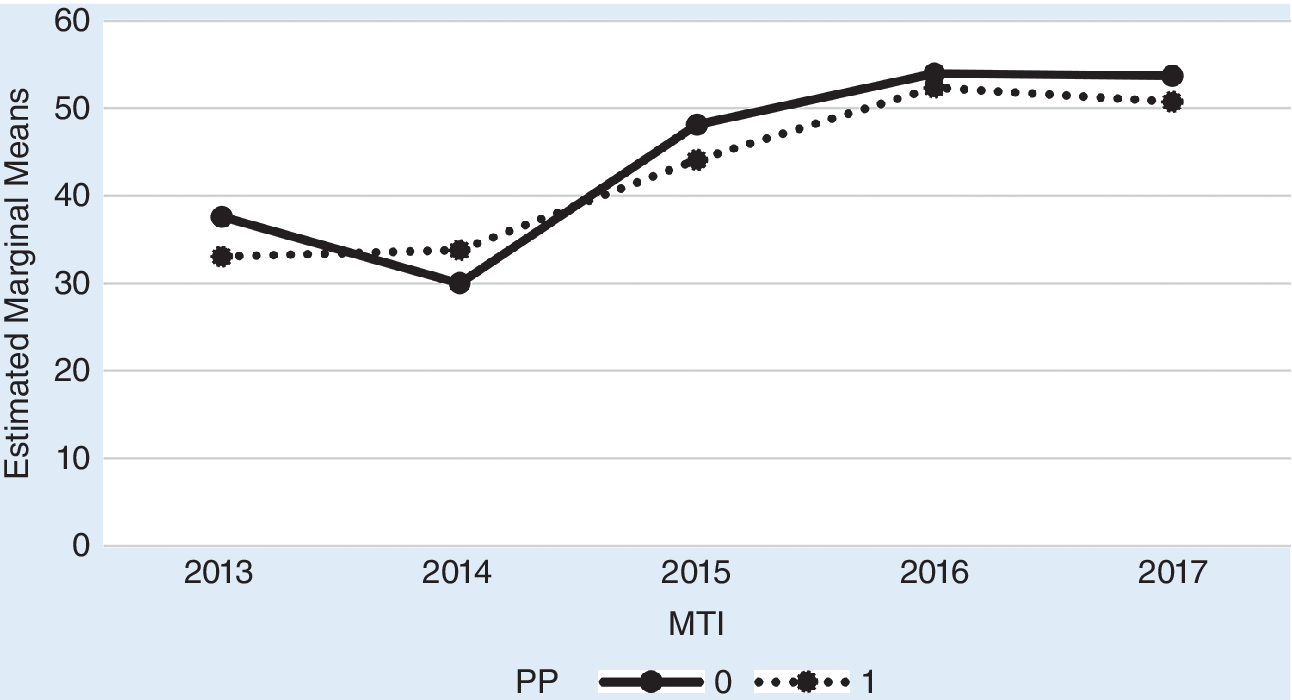

Figure 2 Estimated Marginal Means of MTI (1-Political Parties versus 0-Independent Groups)

Figure 2 shows that MTI growth reached a peak in 2016 in both groups of local government: an annual growth rate of 8.6% and 10.7% for independent (non-partisan) groups and for political parties between 2013 and 2017, respectively.

Model

We conducted a statistical analysis using generalized linear models in which the data were linked to covariates and random effects through an appropriately chosen likelihood and a link function (McCulloch, Searle, and Neuhaus Reference Searle, McCulloch and Neuhaus2008). We denoted by

![]() $ {y}_{jt} $

the transparency level (scaled as MTI/100; i.e., 0<

$ {y}_{jt} $

the transparency level (scaled as MTI/100; i.e., 0<

![]() $ {y}_{jt} $

<1) in municipality j and year t; and by

$ {y}_{jt} $

<1) in municipality j and year t; and by

![]() $ {x}_{jt} $

the binary covariate that takes the value 1 if municipality j in year t is governed by a political party and 0 otherwise. We assumed that

$ {x}_{jt} $

the binary covariate that takes the value 1 if municipality j in year t is governed by a political party and 0 otherwise. We assumed that

![]() $ {y}_{jt} $

follows a Beta distribution—one of the most common distributions for model rates and proportions—which is useful when the variable of interest is continuous and restricted to the interval (0, 1) and is related to other variables through a regression structure (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto Reference Ferrari and Cribari-Neto2004). Regarding the Bayesian hierarchical structure that was followed, the main advantage was the flexibility and the capability of dealing with correlation structures in space and time (Albert and Hu Reference Albert and Hu2019; Turkman, Paulino, and Müller Reference Turkman, Paulino and Müller2019). More specifically, we assumed the following Bayesian hierarchical structure (Brás, Pereira, and Dowley Reference Brás, Pereira and Dowley2023):

$ {y}_{jt} $

follows a Beta distribution—one of the most common distributions for model rates and proportions—which is useful when the variable of interest is continuous and restricted to the interval (0, 1) and is related to other variables through a regression structure (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto Reference Ferrari and Cribari-Neto2004). Regarding the Bayesian hierarchical structure that was followed, the main advantage was the flexibility and the capability of dealing with correlation structures in space and time (Albert and Hu Reference Albert and Hu2019; Turkman, Paulino, and Müller Reference Turkman, Paulino and Müller2019). More specifically, we assumed the following Bayesian hierarchical structure (Brás, Pereira, and Dowley Reference Brás, Pereira and Dowley2023):

Data | Parameters

-

1. Parameters | Hyperparameters

$$ \mathrm{logit}\hskip0.35em \left({\mu}_{jt}\right)\;\alpha +{x}_{jt}^{\prime}\beta +{w}_j+{w}_t $$

$$ \mathrm{logit}\hskip0.35em \left({\mu}_{jt}\right)\;\alpha +{x}_{jt}^{\prime}\beta +{w}_j+{w}_t $$

$$ {w}_j \mid {\tau}_1\sim \mathrm{i}.\mathrm{i}.\mathrm{d}.\mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{\tau}_1\right) $$

$$ {w}_j \mid {\tau}_1\sim \mathrm{i}.\mathrm{i}.\mathrm{d}.\mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{\tau}_1\right) $$

$$ {w}_t \mid {\tau}_2\sim \mathrm{AR}(1)\;\left({\tau}_2\right) $$

$$ {w}_t \mid {\tau}_2\sim \mathrm{AR}(1)\;\left({\tau}_2\right) $$

$$ \alpha \sim \mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{10}^6\right) $$

$$ \alpha \sim \mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{10}^6\right) $$

$$ \unicode{x03B2} \sim \mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{10}^6\right) $$

$$ \unicode{x03B2} \sim \mathrm{N}\;\left(0,{10}^6\right) $$

where α is the intercept, β is the fixed effect,

![]() $ {w}_j $

is the unstructured regional random effect, and

$ {w}_j $

is the unstructured regional random effect, and

![]() $ {w}_t $

is the structured temporal random effect. The unstructured regional random effect allowed the heterogeneity between the municipalities to be considered, whereas the structured temporal random effects allowed the temporal dependence between the observations to be considered. For the regression coefficients, we assumed the following noninformative priors:

$ {w}_t $

is the structured temporal random effect. The unstructured regional random effect allowed the heterogeneity between the municipalities to be considered, whereas the structured temporal random effects allowed the temporal dependence between the observations to be considered. For the regression coefficients, we assumed the following noninformative priors:

-

2. Hyperparameters

log

$ {\tau}_1 $

∼ logGamma(1, 0.0005)

$ {\tau}_1 $

∼ logGamma(1, 0.0005)log

$ {\tau}_2 $

∼ logGamma(1, 0.0005)

$ {\tau}_2 $

∼ logGamma(1, 0.0005)

We assumed noninformative priors for the hyperparameters.

The inference was made using the Integrated Nested Laplace Approximations, known for its computational efficiency, as an alternative approach to the Markov Chain Monte Carlo for Bayesian inference (Rue, Martino, and Chopin Reference Rue, Martino and Chopin2009).

RESULTS

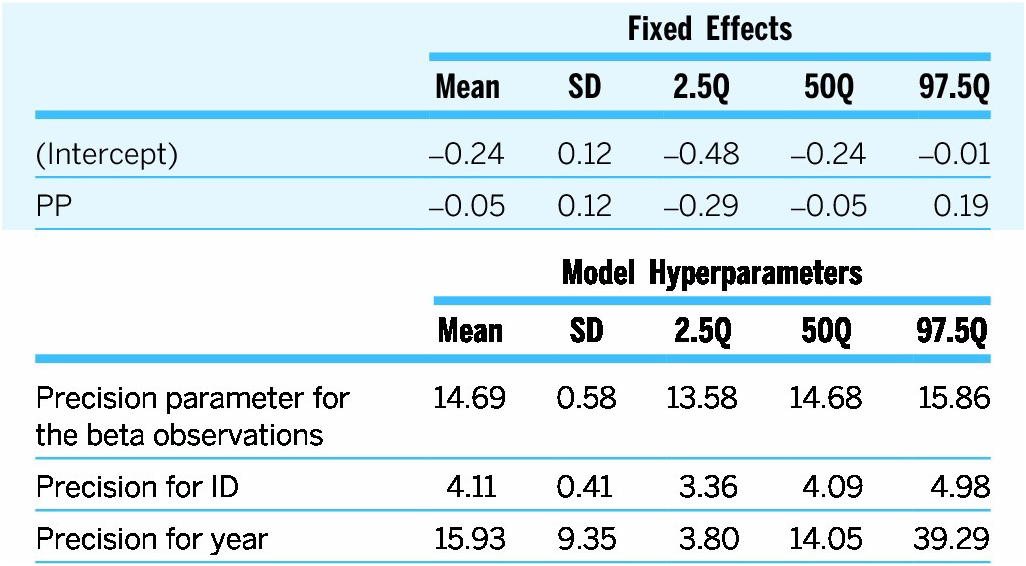

The results are displayed in table 2. As shown in the table, the 95% credible interval for regression coefficient

![]() $ \beta $

includes the value 0, indicating that the dummy PP is not a significant variable in this model. Thus, there is no statistical evidence that the two government groups present different transparency levels. We note that the proposed methodology is robust for imbalanced covariates. Although some techniques for unbalanced panel data could be used (e.g., under-sampling methods), the results did not differ from the results obtained using the original dataset.

$ \beta $

includes the value 0, indicating that the dummy PP is not a significant variable in this model. Thus, there is no statistical evidence that the two government groups present different transparency levels. We note that the proposed methodology is robust for imbalanced covariates. Although some techniques for unbalanced panel data could be used (e.g., under-sampling methods), the results did not differ from the results obtained using the original dataset.

Table 2 Posterior Mean, Standard Deviation, and 95% Credible Interval for the Parameters and Hyperparameters of the Model

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

This study asks whether there were any significant differences in transparency levels found between municipalities governed by independent (non-partisan) groups and those of the majority of municipalities governed by mayors from national political parties. The question is increasingly relevant—in Portugal and Europe more broadly—because the number of “independent” and nonaligned lists are becoming more common, and few scholars have examined what the consequences of this trend might be for local-level transparency. However, our analysis does not reveal a significant difference in MTI scores for each type of municipal government.

There are several potential explanations for this non-finding. The similar scores across the time frame may be explained by the fact that even mayors with party affiliation are becoming more independent and making non-ideological decisions (Kukovic et al. Reference Kukovic, Copus, Hacek and Blair2015). Because mayors often may make policy decisions without considering the guidelines of their political party, the segregation between local governance (i.e., partisan versus non-partisan groups) may be “diluted,” which may have impacted our results. Moreover, given that political parties often are studied as drivers of local transparency (see Brás and Dowley Reference Brás and Dowley2021; del Sol Reference del Sol2013; Araújo and Tejedo-Romero Reference Araújo and Tejedo-Romero2016), in competitive political landscapes, it makes sense that independent (non-partisan) groups also may strive to achieve local transparency. In other words, municipalities governed by mayors with party membership as well as those governed by independent (non-partisan) groups have incentives to promote local transparency in competitive environments. Recent experimental and survey work in Portugal suggests that voters reward party efforts to increase transparency (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Coroado, de Sousa and Magalhães2023).

Another explanation may be the fact that the coordination, organization, and commitment typically displayed by political partisans (Ypi Reference Ypi2016) might attenuate the independent (non-partisan) groups’ advantage of being closer to citizens’ demands (Vampa Reference Vampa2016) in a context in which less-politicized environments favor online open governments (Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Feeney2017). Furthermore, it has been suggested that the mere presence of non-partisan lists as an option has increased voter interest in local elections, increased turnout, and increased electoral competition—all potentially positively reinforcing pressure to pursue transparency efforts (Almeida Reference Almeida2022).

Whether or not cumulatively, these circumstances may explain the similarity between the local transparency of these governance typologies (i.e., partisan versus non-partisan groups), which has theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical point of view, assuming that citizen participation is critical to foster local transparency (Kim and Lee Reference Kim and Lee2019), it is reasonable to point out that cooperation between citizens and municipalities to promote local transparency and accountability need not depend on governance typologies (i.e., partisan versus non-partisan groups). In practice, our findings show that there is room for growth on both sides of the local-governance typology, putting pressure on partisan and non-partisan mayors to increase local transparency. This is important to consider because countries as diverse as Sweden, Germany, Portugal, and Poland allow ILLs to compete in municipal contests. Other countries soon may follow if it can be shown that the presence of ILLs in local elections results in more competition; more engagement and citizen participation; and, therefore, more responsive, transparent, and accountable local governance.

Whether or not cumulatively, these circumstances may explain the similarity between the local transparency of these governance typologies (i.e., partisan versus non-partisan groups), which has theoretical and practical implications.

Given the small number of cases, our results serve only as a starting point for future avenues of research that could provide a deeper understanding of this phenomenon. The context in which ILLs come into existence could be meaningful, as could the competitiveness of the race (e.g., was an incumbent running or was there a scandal in the prior partisan administration). Moreover, it is worth asking whether it matters if the “independent” mayors were once partisans who have since “defected” from the party (i.e., mavericks) or, instead, political outsiders of the technocratic/managerial ilk? Finally, although there are relatively few independent mayors in our dataset and analysis, recent elections confirm the trend that these non-partisan, citizen-led groups and lists are not going away, providing more cases and more mayors for comparison. These are all fruitful avenues for further research: the 2021 local-government elections resulted in 19 independently led municipalities, which provides more opportunities for comparison.

Moreover, it is worth asking whether it matters if the “independent” mayors were once partisans who have since “defected” from the party (i.e., mavericks) or, instead, political outsiders of the technocratic/managerial ilk?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the editor of PS: Political Science & Politics and anonymous reviewers for suggesting several revisions that significantly improved the article. We also acknowledge the multiple scholars and stakeholders who participated in the development of the Municipal Transparency Index in Portugal and for making it available to the public. The first author acknowledges the support action (CSA) ERA Chair BESIDE project financed by the European Union’s H2020 under Grant Agreement No. 951389, DOI10.3030/951389, and the financial support of the Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM) by FCT/MCTES (UIDP/50017/2020+UIDB/50017/2020+LA/P/0094/2020), through national funds. The second author was partially supported by national funds through Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under Project No. UIDB/00006/2020.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OBXSJT.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.