A growing body of literature on political science education shows that games and simulations are effective in helping students better understand abstract theories and concepts (Brown Reference Brown2018; Frank and Genauer Reference Frank and Genauer2019; McCarthy Reference McCarthy2014; Rittinger Reference Rittinger2018). Simulations are useful in illustrating how real institutions work and how decisions in the real world are made within specific institutional structures. Games also are a useful way to illustrate how theories work and how they might apply to real-world settings (Asal Reference Asal2005, 360). It is important for instructors to create game or simulation rules that precisely reflect the theories or reality they want to emphasize (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Jahanbani, Lee and Ren2018; Mendenhall and Tutunji Reference Mendenhall and Tutunji2018; Sears Reference Sears2018).

What if students, rather than instructors, designed games based on political science and international relations (IR) theories? This article describes a project-based course entitled “International Relations and Games” in which students were required to create game rules and scenarios using IR concepts, theories, and topics. Although students learned through participation in games and simulations in previous courses, in this course, they learned by developing their own games—a case of “learning by creating.”

Although students learned through participation in games and simulations in previous courses, in this course, they learned by developing their own games—a case of “learning by creating.”

Game-creation activities share pedagogical advantages with game-playing and simulation activities. They help students to better understand political science theories and concepts and to be more engaged, motivated, and interested in the study of political science. In addition, game-creation activities have other advantages. First, they facilitate peer-based and self-directed learning (SDL). To create a game, students must share and discuss their knowledge and understanding of IR with one another on an ongoing basis and also conduct library and website research to acquire additional knowledge and information when needed. Second, because game creation is an idea-generating activity, it helps improve students’ creativity. Third, it enables students to understand the importance and utility of discipline in the world beyond the classroom.

Existing literature shows the positive role of active-learning strategies such as peer-based learning or peer instruction (PI) and SDL in improving students’ conceptual understanding, problem-solving ability, and analytic skills (Crouch and Mazur Reference Crouch and Mazur2001; Knight and Brame Reference Knight and Brame2018; Knowles Reference Knowles1975). This effect has been observed in multiple disciplines in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Vickrey et al. Reference Vickrey, Rosploch, Rahmanian, Pilarz and Stains2015). However, attempts to apply PI and SDL in political science and IR and to identify their effect have been relatively rare. Because game-creation activities can promote productive and effective peer interactions and self-formulated learning, it can be an instructional practice to test the utility of PI and SDL in political science and IR.

This article first provides a course outline and introduces three game-creation group projects. It then reports the processes and outcomes of the group projects and evaluates their effectiveness in achieving these pedagogical advantages by analyzing the results of a class-participant survey. Finally, conclusions and additional issues are discussed to improve future game-creating activities.

CLASS OUTLINES AND PROJECT DESIGN

This course was offered in the 2018 fall semester at the Department of International Relations of Yonsei University in South Korea. The course format consisted of lectures and group activities. The lecture sessions were presented in a traditional format, introducing students to basic IR approaches, theories, concepts, terms, themes, topics, and contemporary global issues of IR. Although it was a typical introductory-level IR course, a key difference of these lecture sessions was that students had to remember that, later in the course, they would create game rules based on what they had learned.

Three game-creation group projects, summarized in table 1, were assigned during the semester. The first involved making a board game using major IR approaches such as realism, liberalism, and Marxism. Students were required to use the basic game format of Monopoly in which players took turns rolling the dice and moving their token the required number of spaces (boxes). With the exception of this basic format, all other rules of the game were devised by the students. Monopoly was chosen because it is a popular board game and most students were already familiar with its rules. The students were told explicitly that the aim of the project was to help them use group activities to better understand IR approaches and theories. Therefore, by presenting their games, they could demonstrate how well they understood the IR approaches and theories presented in the lectures. At the same time, it was emphasized that the games should be interesting. Therefore, the project evaluation was based on how well the game reflected IR approaches and theories (70%) and how interesting it was to play it (30%).

Table 1 Class Outlines

The second group project involved developing a marketing strategy using a gamification method. Gamification is the application of game elements and rules in non-game contexts, such as marketing. Each group designated a specific product and developed a marketing strategy to sell that product in a specific foreign market of their choice. Because all students had taken at least a couple of courses in comparative politics (e.g., politics of China and political economy of Southeast Asia), they were asked to share their knowledge and use it to help the group choose a country. In addition, it was emphasized that the two most critical factors of their gamification ideas should be competition and excitement. Consumers should compete with one another while having fun and feeling excitement. The primary purpose of this project was to encourage students to teach and learn from one another about specific areas or states and to conduct additional research if necessary. The utility of games in real-world situations also was emphasized. In other words, students were encouraged to devise ideas that real companies would be willing to acquire to increase their sales. The evaluation for this project was based on how well the game reflected the group’s knowledge of the target country and market (50%) and how well they included the two key factors (50%).

The final group project, the most important of this course, involved the students creating and presenting an online game scenario using IR theories, concepts, topics, and contemporary issues. The students were first introduced to existing online games based on the scenarios of war, state building, and elections to provide tips while also emphasizing that they were not allowed to copy existing game scenarios. These projects were evaluated on how well the scenarios reflected IR aspects (50%) and by a professional game developer who evaluated the commercial value of the scenarios in the real game market (50%). In addition, another game developer was invited as a special guest lecturer to give the students a better understanding of the real game market. This special lecture took place a month before the students’ final presentations.

All course outlines and presentation guidelines were specified in the syllabus and were introduced to students during the first week of class. The first group project was presented immediately before the midterm period; the other two were presented four weeks later; thus, students had approximately one month to prepare each project. One third of regular lecture sessions were assigned to in-class group discussions, during which students prepared their projects. During these discussions, the lecturer encouraged and sometimes helped students while also observing how they carried out their projects. The lecturer was concerned with how the students engaged in peer-based learning and how that affected the processes and outcomes of group projects. Students were assigned to different groups for each project, giving them the opportunity to interact with different members of the class.

Of the 21 students enrolled in the course, all majored in IR and had taken introductory and higher-level IR courses; 10 students had taken courses in which playing games or engaging in simulations was part of class activity. The 21 students were divided into five groups to accomplish the three projects. Everyone agreed to sign a form indicating that group members would share equally any benefits generated by their group activities.

PROCESS AND OUTCOMES

In the first project, groups developed board-game rules based on an approach of their own choice. Overall, students successfully demonstrated that they could use the keywords and concepts of each IR approach and create rules that effectively reflected their meanings and implications. For example, one group created a board game based on liberalism. In the game, if a state made a decision to increase its official development assistance (ODA) budget and assist less-developed countries, it benefited by receiving a special card. This rule was based on the liberal assumption that cooperation among states brings about mutual benefits (i.e., a win-win situation). In addition, if a state was caught in a financial crisis, all other states were automatically damaged to some degree, emphasizing economic interdependence and globalization. Table 2 summarizes the outcomes of the first project.

For example, one group created a board game based on liberalism. In the game, if a state made a decision to increase its official development assistance (ODA) budget and assist less-developed countries, it benefited by receiving a special card.

Table 2 First Group Project Outcomes

In the second project, students used their previous knowledge of specific countries or areas to develop effective and interesting gamification strategies. They predominantly focused on rivalry because the importance of competition had been emphasized during lectures. The groups chose specific cases of rivalry between two countries or between regions or provinces within a country and then designed games in which consumers competed to buy more to gain a competitive advantage over their counterparts. All groups developed an essentially similar game format: when consumers bought a product and scanned a product’s Quick Response code using their smartphone, a score was added to the specific country or region chosen by the consumer. In this way, the game made consumers compete against one another. For example, one group, which chose China, was supposed to export a banana-flavored milk drink to Chinese consumers. When buying this milk, consumers had to select a province that belonged to one of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient China—Wei, Shu, or Wu. This idea was based on the famous Chinese novel, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. If people in the province of Sichuan bought more milk, the ancient kingdom Shu earned more power in the animation application shown on the consumers’ smartphone. Results of the competition were released on a monthly basis and special offers were provided for the winning provinces.

In the third project, students used IR concepts, terms, and topics such as sovereignty, sustainable development, global warming, and the Syrian Civil War, concepts which had been introduced during lectures. For example, one group created a scenario titled “The Age of the Ark” in which global warming and rising sea levels had submerged all land; survivors had built boats to live on the seas. The boats were the new sovereign states and players were responsible for their boat’s survival and development in a self-help system. The boats went to war and captured the resources of others. The player who secured a certain amount of national power within a given time won.

In the personal interviews conducted in the final week, 10 students noted that maintaining a balance between the game’s IR aspects and its commercial value proved challenging. They were concerned that a professional online game developer would evaluate their projects. However, all of the students reported that the evaluation system of this final project provided a unique opportunity to realize the utility of the discipline. Two groups used the basic format of existing popular online games and changed or added some of the rules, whereas the other three groups created completely new games. However, this difference was not a factor in the grades they were awarded by either the course coordinator or the games specialist.

EVALUATION

In all three projects, students actively exchanged knowledge, ideas, and opinions. They frequently taught and debated one another. They also conducted research by searching websites and reading online material to gain a deeper understanding of contemporary global issues central to the games they created. When students asked questions, they first were encouraged to share their answers with one another, and only then were the opinions of the lecturer voiced. They constructed knowledge together, providing insights and motivation to one another (Asal Reference Asal2005, 362). Therefore, PI and SDL were the main driving forces for the effective implementation of group projects and successful outcomes. Ideas were generated and sharpened during these learning processes, making the students more engaged, attentive, and active. The projects promoted positive interdependence among students (Zeff Reference Zeff2003). These results confirm the findings of previous research on the benefits of active-learning strategies (Johnson and Johnson Reference Johnson and Johnson2009; Ruben Reference Ruben1999; Sears Reference Sears2018).

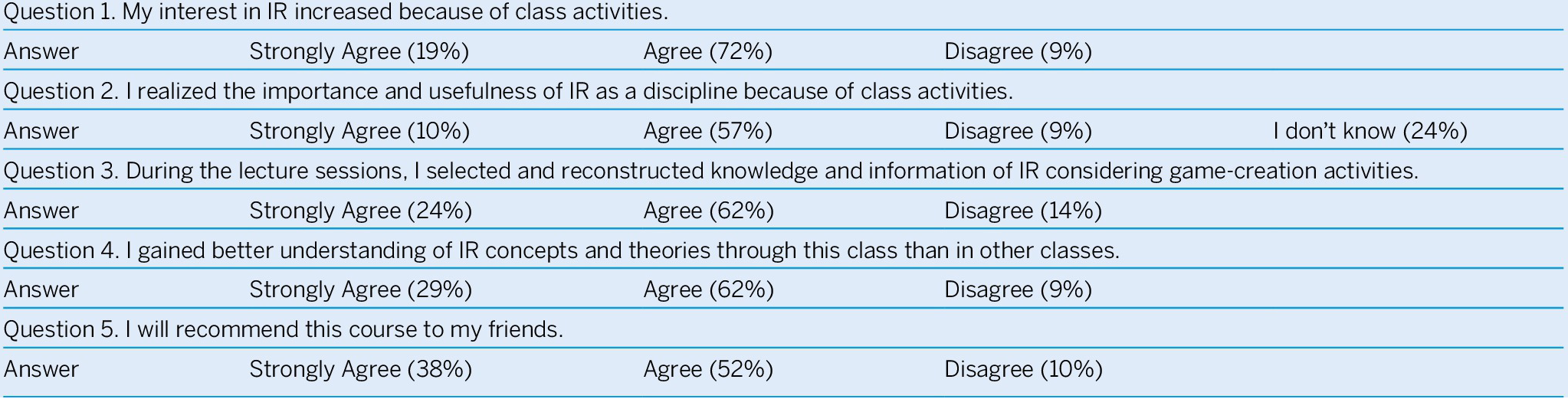

At the end of the semester, a survey and personal interviews were conducted. As shown in table 3, students’ responses were generally positive. They gained a new and better understanding of IR, realized the importance and usefulness of the subject, and experienced knowledge reconstruction through PI and SDL as well as lecture sessions. Overall, they were highly satisfied with the course.

Table 3 Survey Results

During the interviews, students were asked more specific questions about the course. They were asked whether, in the final project, it might be better to require students to create games based on topics suggested by the instructor—for example, a game of US–China competition that would evaluate how seriously the game reflected the nature of relations between the two countries with reference to IR theories and concepts. Almost all students (20 of 21) disagreed with this suggestion and believed it would cause them to be less engaged and less creative.

Ten students had previous experience playing games and simulations in other political science courses. When asked to reflect on the differences between those game-playing activities and the game-making activities of this course, they said that in other simulations, they felt that they were the subjects of the experiment: “lab rats,” in other words, who passively followed instructions until they realized the message of the simulation. In contrast, in this course, they felt as if they were leading the class because they not only discussed and taught one another but also created games that might be used in other IR courses. In other words, creating games made them feel more like teachers than students. Similarly, two students emphasized that creating games required creativity, insight, critical thinking, and communication skills, whereas the key to success in game playing was correctly and promptly understanding the rules of the game. In addition, all 10 students said that game creation was more exciting, fun, novel, and innovative than previous game-playing activities.

Notably, two students commented that after commencing these projects, they subsequently found existing online games using IR content to be unrealistic, too simplistic, and overwhelmingly male dominated. A student noted that existing games are based predominantly on the realist perspective, with the state as the basic unit, and where hard power is increased through competition for material interests such as natural resources. In these games, international cooperation is never an option and the role of international institutions is minimized. Indeed, even games designed to teach realism often are too rigid in their emphasis on core realist assumptions, making it difficult for students to recognize the limitations of realism (Mendenhall and Tutunji Reference Mendenhall and Tutunji2018).

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

Game creation motivates students to participate in the teaching and learning process and helps them more effectively understand IR approaches, theories, and concepts. Unlike game-playing activities in previous IR courses, students in this course led the class in selecting, constructing, and utilizing their knowledge to create IR games. They shared their understandings, taught and learned from one another, and conducted the background research required to create IR games. In these ways, this was a unique experience for the students.

…students in this course led the class in selecting, constructing, and utilizing their knowledge to create IR games. They shared their understandings, taught and learned from one another, and conducted the background research required to create IR games.

The game-creation course can be further developed in three ways. First, it could be designed as a flipped class by which students could learn class content watching lecture videos or PowerPoint presentations before class, with class time devoted to engaging in group discussion and activities. Second, one student commented that having a non-Korean group member would have given the group a new perspective and better understanding of that student’s country. Because the university has a large international student population, it would be interesting to incorporate students from different countries into the game-creation process to observe how they interact and share ideas and how different their final outcomes might be from those produced by Korean students. Third, as mentioned previously, the course content taught in class can be reduced to a certain degree—for example, teaching international political economy (IPE) rather than general introductory-level IR. Lectures on specific IPE topics, such as World Trade Organization dispute-settlement mechanisms and various versions of exchange-rate systems, could be given wherein students would be required to create games based on these topics. Although students might feel a greater burden if the scope of topics for game creation was limited, it ultimately would save time because they could focus directly on the given topic. In addition, professors could obtain a clearer understanding of the students’ grasp of the topic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Hyuk Seo for his enormous help and encouragement, Sujin Ri for her wonderful lecture as a guest speaker, and Ji-Ae Lee for her useful comments and advice.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials are available on Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JCO5EI.