This research builds on and extends the database of 3,715 faculty created for “The Political Science 400: A 20-Year Update” by Masuoka, Grofman, and Feld (Reference Masuoka, Grofman and Feld2007a) and used in subsequent work by these authors (Fowler, Grofman, and Masuoka Reference Fowler, Grofman and Masuoka2007; Masuoka, Grofman, and Feld Reference Masuoka, Grofman and Feld2007b; c), later updated by Kim and Grofman (2019; hereafter KG).Footnote 1 The original Masuoka, Grofman, and Feld (hereafter MGF) dataset includes a record of all regular faculty members at the 132 US political science PhD-granting institutions ca. 2002 and provides supplementary information such as the date of PhD, the institution from which the PhD was awarded, and individual faculty citation counts from 1965 to 2005,Footnote 2 as well as gender coding.Footnote 3 We build also on the KG (Reference Kim and Grofman2019) update of the original MGF database that identifies where the original set of scholars are ca. 2017. We supplemented the original MGF and subsequent KG coding by including the rank currently held by individual faculty—based on our hand coding of departmental and individual websites—and the prestige level of departments.Footnote 4

Using these data, we asked related questions about indicia of professional success and correlating factors. Although our primary focus was on what has happened to faculty in the 2002 dataset who were still in non-emeritus status ca. 2017 in the intervening period, we also mention data in the 2017 faculty dataset.Footnote 5 We reviewed several overall indicators, looking particularly at the gender gap.Footnote 6 However, before discussing the central questions of our investigation, we summarize descriptive information about our datasets. We found dramatic changes over time in the cohort and gender compositions of the PhD-granting departments.

A substantial proportion of those with jobs in PhD-granting departments in 2002 are now either emeritus or deceased (33%).Footnote 7 Of those remaining, nearly 95% have stayed in academia with either a faculty appointment (93.4%) or an administrative appointment (1.2%). We found that roughly 90% of this set remains at US PhD-granting institutions, the majority at the same institution they were listed at in 2002; 7.3% have academic positions at US non-PhD-granting institutions; and 3% currently have jobs at academic institutions outside of the United States.Footnote 8 Of these, more than 77% are full professorsFootnote 9 and a non-trivial proportion of more than 22% who are 15 years or more past their PhD are still at the associate-professor rank or lower.Footnote 10 Moreover, among this dataset, only 18% of male scholars remain at the associate-professor rank or lower whereas more than 33% of female scholars remain at the same level.

Moreover, among this dataset, only 18% of male scholars remain at the associate-professor rank or lower whereas more than 33% of female scholars remain at the same level.

Among those for whom we coded for gender in the full 2002 dataset, there were 2,930 (78.9%) male scholars and 758 (21.1%) female scholars. Among the tenured or tenure-track faculty at PhD-granting departments in the 2017 dataset, moreover, there were 2,955 (72.3%) male scholars and 1,135 (27.8%) female scholars. This shows that the proportion of female faculty with R1 jobs is rising, albeit very slowly.

We can see more clearly what has been happening to the gender composition of the profession by disaggregating the 2017 data into five-year cohorts. The proportion of female scholars teaching at PhD-granting departments has grown steadily over time: the pre–1970 cohorts had female representation in the single digits; 12.88% of members in the 1970–1974 cohorts were female; and the 1975–1999 cohorts had female representation in the 20% range. In the most recent (partial) cohort, women comprise 39.8% of faculty who have been hired (the full data are omitted due to limited space; see appendix J).Footnote 11

Another important piece of descriptive data is information on the citation counts of faculty categorized by both cohort and gender. Table 1 shows average citation numbers for the full dataset of 2002 faculty, based on the Social Sciences Citation Index data reported by MGF.

Table 1 Average Citation Numbers for the 2002 Dataset of Faculty at Phd-Granting Departments By Cohort, Based on the Social Sciences Citation Index Data Reported By MGF

The male-female citation ratio show that men are almost always cited more than women. Moreover—and rather surprisingly—the gap has increased over time. Similarly, the 2017 data set of political science faculty continues to show similar trends.Footnote 12

KEY QUESTIONS ABOUT GENDER DIFFERENCES

For the non-emeritus 2002 faculty in 2017, we examined status changes during the intervening period. For example, if a faculty member changed institutions within the dataset of PhD-granting departments, were there gender differences in whether the shift was to a PhD-granting department of greater prestige, of the same or lesser prestige, or to another type of job? Similarly, were there gender effects in terms of likelihood of achieving tenure or full-professor rank?

In addressing these questions, we were careful to consider differences in date of PhD (in terms of five-year cohorts). This control was especially critical in understanding gender differences in professional success because women currently comprise a higher proportion of job holders than in the past. Failure to use this control would risk confounding ecological compositional effects with causal patterns because men, on average, have had greater seniority due to historical gender gaps and thus are more likely to have higher rank and professional visibility.

We also considered the effects of controlling for citation counts, which we found to be an important factor in accounting for differences in various indicia of professional success. We discuss the impact of the interaction of citations and gender on professional success in a subsequent section. However, citations can be a gender-biased measure. Studies have shown that women are less likely to cite themselves than men (Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013); men are less likely to cite women scholars than male scholars (Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013); and edited books are disproportionately edited by men (with the striking exception of gender studies) (Mathews and Andersen Reference Mathews and Andersen2001).Footnote 13

Status Change in Terms of Movement across Departments

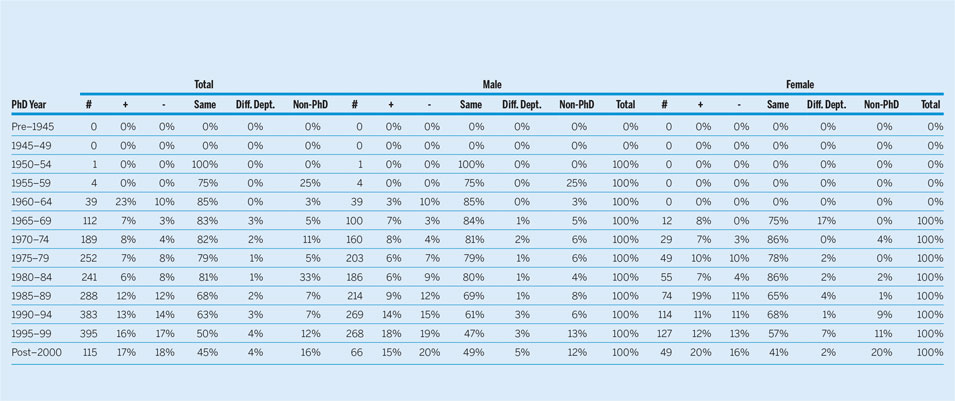

How likely were the non-emeritus 2002 faculty in 2017 to have made a change in jobs between 2002 and 2017 that involved an upward or downward movement in university ranking? Furthermore, is there a gender-related pattern to the directionality of change? Table 2 shows the proportion of non-emeritus scholars with an academic position in the United States who are currently at the same university that they were in 2002,Footnote 14 categorized by gender. The table also provides data on those who moved to another academic position in the United States ca. 2017. For example, the table shows whether they moved to a non-PhD-granting institution. For those who changed institutions but remained at a US PhD-granting department, table 2 also shows whether the 2017 department was ranked higher, lower, or the same as the 2002 department by using the 2017 ranking of political science departments in US News and World Report.Footnote 15

Table 2 Movement of 2002–2017 Non-Emeritus Faculty by PhD-Granting vs. Non-PhD-Granting, and University Rank Change for Those Staying at US R1 Institutions, with Further Breakdown by Gender

Notes: “#” means the total number of people within each group. “+” stands for an increase in ranking; “-” implies a decrease in ranking. “Same” means that scholars remain at the same department. “Diff. Dept.” refers to those who are at different departments that are similarly ranked with their previous institutions (within five ranks). “Non-PhD” refers to the proportion of those who moved to non-PhD-granting institutions.

The data show that the majority of non-emeritus faculty who were employed at a PhD-granting department in 2002 were at that same university in 2017. Remarkably, among those who moved, movement was as likely to a more prestigious as to a less prestigious department. The same is true for both men and women. Also, men and women were roughly equally likely to move to a job that was not at a PhD-granting university. Moreover, younger cohorts—who are still in the process of establishing themselves within the profession—had higher proportions of taking positions at non-PhD-granting departments.

Status Change in Terms of Tenure and Promotions

Older cohorts had fewer women in terms of both those teaching at PhD-granting departments and the pool of PhDs from which such faculty are drawn. This has a downstream effect as most full professors are men, largely because they disproportionately come from older cohorts. A key question is whether these representational differences can be explained over time by gender differences in PhD production at universities that provide most of the faculty who teach at PhD-granting universities. According to Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Htun, Rosenbluth, Thelen and Walsh2017), female PhD students comprised nearly half of the student body at the largest 20 departments in 2012; however, this level of gender representation is not characteristic of earlier cohorts.

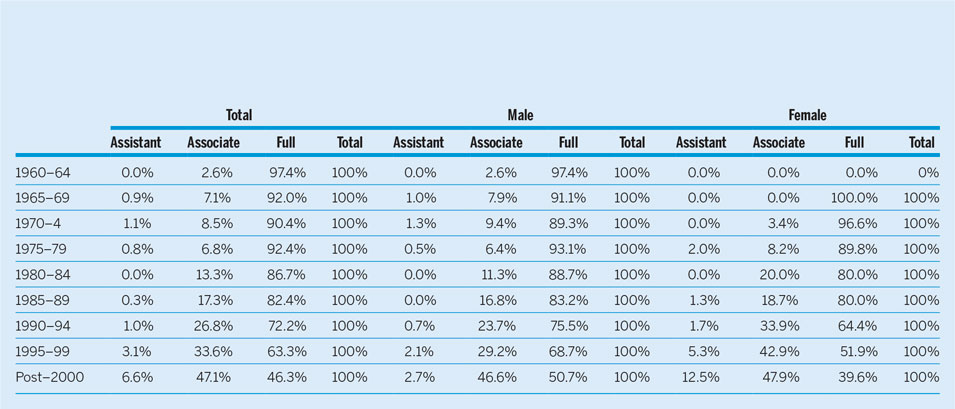

Although we could not directly address this issue, table 3 provides relevant evidence on gender differences that cannot be explained by differences in the proportion of males and females in different cohorts. We examined the proportion of men in each cohort with R1 jobs who became full professors compared to the proportion of women in the same cohort who became full professors. The table shows that except for the earliest cohorts, within each cohort, women were less likely to be full professors and more likely to be assistant professors than men. Among all cohorts, 82% of men were full professors whereas only 66.9% of women were full professors. In the youngest cohort, 50.7% of men were full professors whereas only 39.6% of women were full professors.Footnote 16 Within cohorts, women were overrepresented at the associate-professor rank.

The table shows that except for the earliest cohorts, within each cohort, women were less likely to be full professors and more likely to be assistant professors than men. Among all cohorts, 82% of men were full professors whereas only 66.9% of women were full professors.

Table 3 2017 Rank of Non-Emeritus Faculty in the 2002 MGF Dataset, by Cohort, with Further Breakdown by Gender

ROLE OF CITATION COUNTS

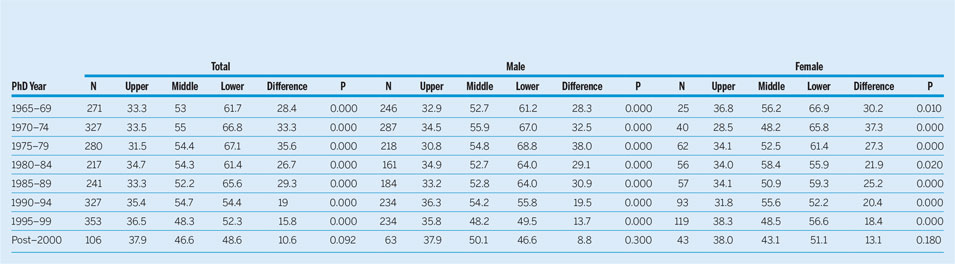

We now discuss the role of citation counts in both present and past placements. We conjectured that those with lower citation counts within each cohort would begin and end at relatively lower-ranked institutions. Within each cohort, we divided the faculty in the MGF dataset into three groups (i.e., the upper, middle, and bottom thirds of citation counts) based on the MGF lifetime citation count using data from the Web of Science. We also categorized the data by gender.Footnote 17

We compared faculty in the upper third of citation ranks to those in the lower third, vis-à-vis the average rank of the department at which they taught ca. 2002, on a scale from 1 to 97 in table 4, using US News and World Reports departmental rankings. Lower numbers indicate higher-ranked departments. As shown in table 4, those in the upper third of their cohorts, regarding their citation counts, were located at considerably higher-ranked universities in 2002 than those in the bottom third.Footnote 18 The difference-of-means test for each cohort was statistically significant for all except one cohort.Footnote 19

Table 4 Effects of Citation Counts on Gender Differences in Rank of Department of Employment

Thus, citation counts are important in explaining differences in placement. Moreover, these statistically significant differences in placement ranking, according to citation counts, hold separately for both men and women. Similarly, Grofman (Reference Grofman2009) demonstrated that for University of California political science faculty, citation counts are a good predictor of salary levels once the date of PhD is taken into account.

We expect that table 4 understates the importance of citation counts for professional success at the research-university level because our dataset includes only those who already had a job at a PhD-granting department. We expected that the average citation differences between those employed at PhD-granting departments and those with other types of political science jobs would be significant. However, we also think that the causal arrow goes in both directions because those who are not hired at research-oriented institutions will have more difficulty obtaining the resources needed to publish and, thus, potentially be cited.

The key question of interest is whether highly cited women (i.e., the top third, relative to their cohort) were as highly placed as comparably highly cited men in that cohort. A similar question is asked about those in the bottom and middle thirds of citation counts relative to their cohort overall. We found a mixed pattern. Looking at the upper citation group, for example, the differences were not that compelling—and basically “noise.” Highly cited women were as likely to be highly placed as highly cited men. Similarly, although there was slightly more variation, less cited women (i.e., the bottom third, relative to their overall cohort citation counts) were essentially as likely to be highly placed as men of comparable citation status in their cohort. Among the middle-third citation category, however, we found substantial evidence of gender differences. In summary, while women seem to do as well as men among scholars who are above or below average in terms of citation counts relative to their cohort, it seems easier for middle-ranked men, vis-à-vis citations, to be placed higher than women with comparable citation counts. Moreover, as discussed above, women are less likely to be cited than men in their respective cohorts, and this citation gender gap seems to be increasing. As such, it is possible that the gender gap in placement and promotion, which is influenced by citation counts, may also increase.

DISCUSSION

This article focuses on questions drawn from our integration of 2017 data with the 2002 MGF dataset. We found extensive turnover in terms of retirements and deaths among the set of scholars identified in 2002 as being employed at an R1 US political science department. During this 15-year period, there was a strong generational shift, which is reflected in the present cohort composition of R1 political science departments compared to 2002. There is no clear pattern of upward or downward movement in prestige of institution between 2002 and 2017 among those in the 2002 dataset who were alive and non-emeritus in 2017. However, we found that citation counts (ca. 2002) relative to those among an individual’s own cohort were useful in predicting the prestige level of the institution that a scholar taught at in 2002, as well as the likelihood of a shift to a more or less prestigious institution in 2017.

Regarding gender effects, we examined those 2002 faculty who still had non-emeritus status in 2017; when we controlled for cohort, there was no statistically significant gender differences in retention at a PhD-granting university. There also were no significant gender differences regarding whether these faculty stayed at a non-R1 institution; however, there were significant differences based on cohort.Footnote 20 Moreover, looking at the full dataset of 2017 faculty, we found that male scholars in younger cohorts were more likely to advance to full professorship than their female peers. These differences were not as strong in older cohorts, but this may be due to the fact that there were very few women in those cohorts to begin with.

Women are becoming an increasing proportion of faculty at PhD-granting political science departments. Indeed, if present trends continue, it is not unreasonable to expect gender parity in hiring new faculty in the not-too-distant future.

When we added citation-count data, scholars with higher citation counts relative to their cohort were more likely to be at and stay at more highly ranked departments; this was true for both men and women. However, women in the middle-third group of citation counts relative to their cohort seemed to be disadvantaged in department placement relative to the men in their cohort.Footnote 21

Controlling for citations still may understate gender effects. Citation counts may suffer from gender bias as measures of achievement and visibility. Much of the gender bias in academia (i.e. tenure, promotions, etc.) stems from the gender bias in citation counts. Because female scholars have fewer citations, this gender citation gap makes women less likely (or take longer) to be hired and promoted, less likely to achieve full professorship, and more likely to leave academia (Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Xu Reference Xu2008).Footnote 22 As such, finding a way to fix the gender bias in citation counts in the discipline can help alleviate much of the downstream gender bias.

A note of caution must be added to a too-casual reading of this literature. In particular, we argue for the importance of a control for the date of PhD.Footnote 23 We might expect that the men who publish in a given journal, on average, are older than the women who publish there, simply because of the historical gender structure of the profession and the fact that those who publish continue to include older (and often frequently publishing) as well as younger scholars. However, ceteris paribus, we do not expect the number of citations for work in a journal by relatively younger scholars to be as high as citations to work in that same journal by more senior scholars—for example, those whose work was read by many present faculty members since their graduate school days. How much this potential confound matters can be understood only by controlling for cohort when making gender comparisons. It well may turn out that this type of potential confound, although real, is simply too minor to explain the considerable gender citation differences often found. However, in reanalyzing the Mitchell, Lange, and Brus (Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brus2013) study, Zigerell (Reference Zigerell2015) suggested that much of the observed gender gap is due to gender differences in citations among only relatively few of the most highly cited articles.Footnote 24

We want to conclude this article on an optimistic note. Women are becoming an increasing proportion of faculty at PhD-granting political science departments. Indeed, if present trends continue, it is not unreasonable to expect gender parity in hiring new faculty in the not-too-distant future.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000490

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers at PS: Political Science & Politics and the editors for helpful feedback and comments.