Women remain underrepresented in academic careers despite their increasing participation in doctoral programs. Female scholars submit and publish fewer articles than their male colleagues in political science, with underrepresentation particularly pronounced in certain top journals (Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Edward Sokhey2019; Mathews and Andersen Reference Mathews and Andersen2001; Østby et al. Reference Østby, Strand, Nordås and Gleditsch2013; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017); this mirrors patterns in many other disciplines (West et al. Reference West, Jacquet, King, Correll and Bergstrom2013). Furthermore, across a wide range of fields, women’s work is cited less frequently than research authored by men (Beaudry and Larivière Reference Beaudry and Larivière2016; Ferber and Brün Reference Ferber and Brün2011; King et al. Reference King, Bergstrom, Correll, Jacquet and West2018; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013). Given gender gaps in output and recognition, women are less likely than men to achieve tenure and more prone to depart academia in a pattern often called “the leaky pipeline” (Xu Reference Xu2008).

This article describes one early factor that may contribute to these gaps: students’ low exposure to female-authored readings. If faculty teaching PhD courses (henceforth, “instructors”) largely omit female authors, students may become less likely to cite female-authored work, and they may develop implicit stereotypes regarding the quality of female scholars’ research. Indeed, recent studies confirm that female authors are underrepresented in syllabi in two subfields of political science: international relations and American politics (Colgan Reference Colgan2017; Diament, Howat, and Lacombe Reference Diament, Howat and Lacombe2018; Phull, Ciflikli, and Meibauer Reference Phull, Ciflikli and Meibauer2018).

We analyzed the GRaduate Assignments DataSet (GRADS), which is—to our knowledge—the most comprehensive dataset of assigned graduate readings to date. GRADS includes 75,601 syllabi readings from 840 syllabi and 605 unique instructors at 94 US-based political science departments.Footnote 2 In contrast to prior studies of syllabi in single subfields, the dataset comprises works from across subfields. It also is substantially larger: six times larger than Phull et al.’s sample (n=12,399), 12 times larger than Diament et al.’s sample (n=6,266), and about 23 times larger than Colgan’s sample (n=3,343). This study used GRADS to investigate the relationship between instructor characteristics—gender, race, age, and national origin—and their rates of assigning female-authored work. In another article, we show that contextual factors (e.g., time, department composition, and subfields) also influence these rates (Hardt et al. Reference Hardt, Smith, June Kim and Meister2019).

We report several findings. Across political science, female-authored readings are significantly underrepresented, relative to women’s publication rates in top journals. Underrepresentation is particularly pronounced when considering women as first authors. Instructors’ characteristics affect whether they assign work by women; both identity and socialization appear to play a role. Women, people of color, and instructors socialized in more gender-equal countries all assign more female-authored readings than their peers. Among female instructors, generational cohorts also matter.

We report several findings. Across political science, female-authored readings are significantly underrepresented, relative to women’s publication rates in top-journal articles. Underrepresentation is particularly pronounced when considering women as first authors.

SYLLABI AND THE SOCIALIZATION OF GRADUATE STUDENTS

This study investigated gender representation in syllabi—that is, the proportion of assigned readings that are female authored. Syllabi socialize PhD students (henceforth, “graduate students”) into academia, conveying not only academic content but also implicit and explicit messages about what constitutes model work—and which scholars do that work. Thus, gender representation in syllabi affects how future scholars view and engage with academia.

Similar to studies that document a gender citation gap, we expected to find a gender syllabus gap. Several mechanisms could lead instructors to under-assign work by women. The first mechanism is path dependence. Scholars designing syllabi experience significant time constraints. They tend to assign some of the same readings that they themselves read as graduate students and to seek out relevant syllabi from other instructors. They also may rely on classic works and “elite readings,” in which gender gaps in citation counts are largest (Zigerell 2015). Second, instructors are likely to assign work by well-known scholars; male authors, in general, are likely to occupy more central locations in scholarly networks. However, network effects would lead female instructors to assign more female-authored work than men, given gender homophily.

Third, implicit gender biases could lead instructors unconsciously to favor male-authored readings. Beginning at a young age, individuals adopt the gender stereotypes that women are less brilliant than men and less capable academics (Bian, Leslie, and Cimpian Reference Bian, Leslie and Cimpian2017; Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Cimpian, Meyer and Freeland2015; Williams, Phillips, and Hall Reference Williams, Phillips and Hall2014). Scholars have found evidence of gender bias in academia in evaluations of scholarly work, letters of recommendation, and certain hiring practices (Knobloch-Westerwick and Glynn Reference Knobloch-Westerwick and Glynn2013; Krawczyk and Smyk Reference Krawczyk and Smyk2016; Lee and Ellemers Reference Lee and Ellemers2015; Madera, Hebl, and Martin Reference Madera, Hebl and Martin2009; Rivera Reference Rivera2017). One study observed hiring practices that favor women (Williams and Ceci Reference Williams and Ceci2015).

Because instructors draw on top journals to create syllabi (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), we adopted women’s publication rates in 10 top journals as a benchmark. We expected underrepresentation to be particularly pronounced in first-author positions. Typically, political scientists use alphabetical author order. However, when author order is not alphabetized, we expected male authors to appear earlier in the author list, indicating greater importance.Footnote 3 We hypothesized that:

H1. The proportion of assigned readings with female first authors is significantly lower than the proportion of female-authored publications in top journals.

We expected that instructors from underrepresented groups assign a higher proportion of female-authored readings.Footnote 4 Both men and women of color, as well as white women, are likely to be more aware of barriers to demographic representation, due to both personal experience and informal networks (Brink and Benschop Reference Brink and Benschop2014; McDowell, Singell, and Stater Reference McDowell, Singell and Stater2006). As a result, underrepresented individuals may deliberately diversify syllabi. For example, recent studies found that female scholars cite more female-authored work (Maliniak and Powers Reference Maliniak and Powers2013; Mitchell, Lange, and Brus Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brus2013). We hypothesized that:

H2. Instructors from underrepresented groups assign more female-authored readings than instructors from dominant groups.

We also expected that older female instructors assign more women’s research. Scholars who went through graduate school decades ago likely had little exposure to female-authored research. However, motivation and networks may matter more for older women. Studies show that women socialized during the second wave of feminism are distinctly feminist, relative to subsequent generations (Schnittker, Freese, and Powell Reference Schnittker, Freese and Powell2003). In addition, older female instructors may have larger gender-homophilous networks, including the mentoring of junior women, making them more aware of women’s publications. We hypothesized that:

H3. Older female instructors assign more female-authored readings than younger instructors.

Finally, instructors socialized in more gender-equal environments may assign more female-authored readings due to greater awareness of diversity and perhaps lower gender bias. Indeed, the gender citation gap is smaller in more gender-equal countries and those with higher human development (Sugimoto, Ni, and Larivière Reference Sugimoto, Ni and Larivière2015). Nonetheless, gender inequality in academia does not simply mirror societal gender inequality; rather, national academic institutions structure female academics’ opportunities and challenges (Bain and Cummings Reference Bain and Cummings2000; Husu Reference Husu2000; Le Feuvre Reference Le Feuvre2009). Although many European countries have lower indices of gender inequality than the United States, hierarchy within European universities may create barriers to female instructors’ advancement. Relative to other countries’ political science associations, the American Political Science Association (APSA) “has the longest history of institutionalizing multiple forms of diversity within its organizational structure, beginning in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement” (Abu-Laban, Sawer, and St-Laurent Reference Abu-Laban, Sawer and St-Laurent2018, 15). Hence, European-trained instructors may assign fewer female-authored readings.Footnote 5 We hypothesized that:

H4. Instructors raised in more gender-equal countries and with PhD training in countries with more gender-equal academic hierarchies will assign more female-authored work.

DATA AND METHODS

We collected syllabi through a multiphase process. First, 301 syllabi were obtained from an IRB–registered survey that sampled APSA members teaching in US-based PhD programs; these respondents also answered demographic and institutional questions. Second, contributed collections and online searches yielded another 160 syllabi. Third, graduate-student project affiliates at top-50 programs collected 450 syllabi on our behalf. (See online SI: Methods for more details about our data collection and a discussion of the representativeness of each data-collection component.)

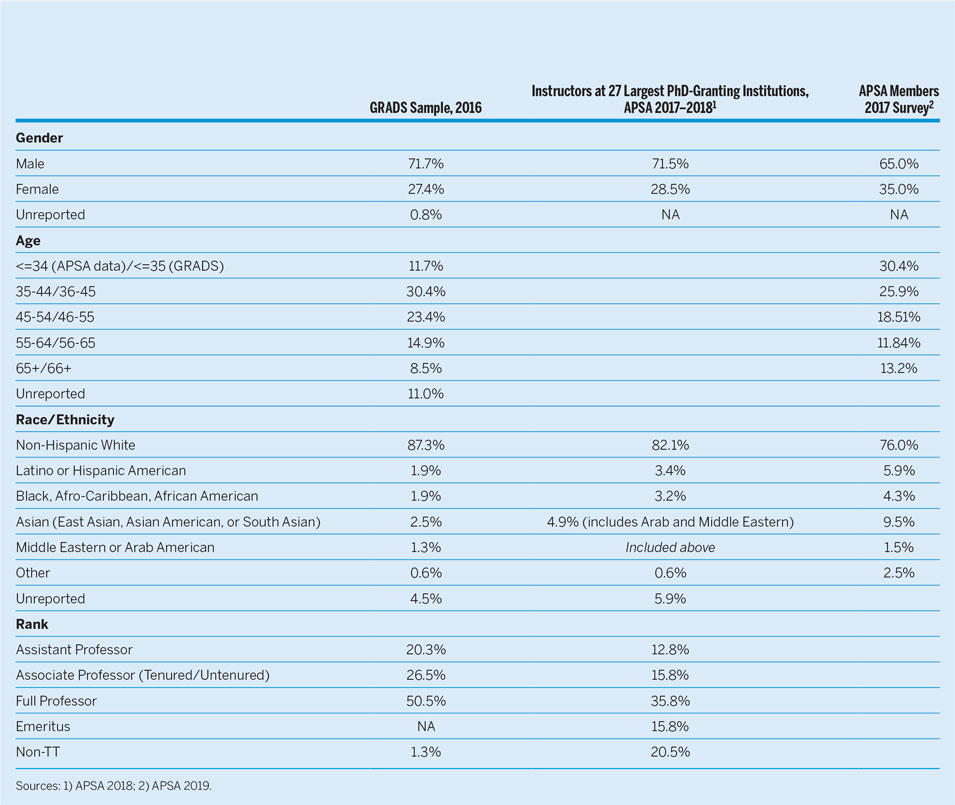

The resulting dataset—GRADS—comprises data at the levels of (1) syllabi, (2) instructors, and (3) assigned readings. We processed readings through a combination of hand-coding and machine-learning to parse the different components (e.g., author name and title). To code author gender, we first matched given names against a list of known political scientists whose names we expected would be coded incorrectly. We then matched remaining given names against existing gender datasets, including those based on US and UK censuses and social media data (see online SI: Methods for a full discussion). Instructor gender was coded by examining online biographies and using the names dataset.Footnote 6 Appendix table 1 compares the GRADS instructor sample to APSA members and faculty in PhD-granting departments in the United States. Although our sample is whiter, older, and more male than the APSA membership, it is comparable to the population of PhD-level instructors.Footnote 7

RESULTS

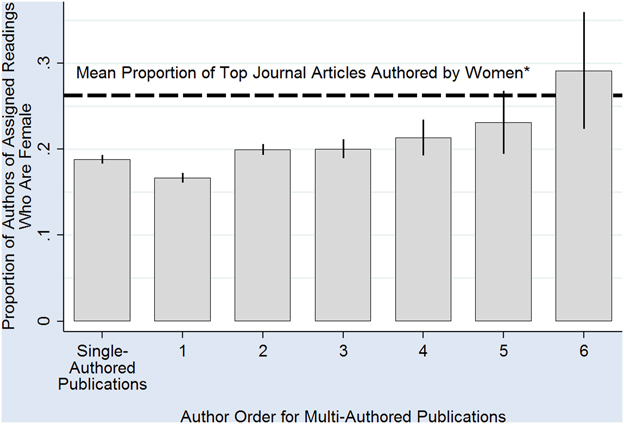

Scholarship authored by women is underrepresented in political science graduate training, overall and within each subfield (see online SI: Results). In support of hypothesis 1, figure 1 shows that the proportion of assigned readings with female-first or only (“solo”) authors (18.5%) is lower than the female-authored proportion of top journal publications. Gender is significantly associated with author order; that is, women are less likely to be first authors than solo or subsequent authors.

Figure 1 Female Scholars Are Underrepresented in Political Science Syllabus Readings Except as Sixth Authors

Notes: *The dashed line represents mean proportion of female-authored readings from 10 leading political science journals from 2000 to 2015 (weighted by number of articles per journal), reported in Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017). Unit of analysis is the reading; data are weighted to account for varying numbers of readings across syllabi. Bars represent mean proportion of female-authored within each author-order category, and whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (based on standard errors of mean).

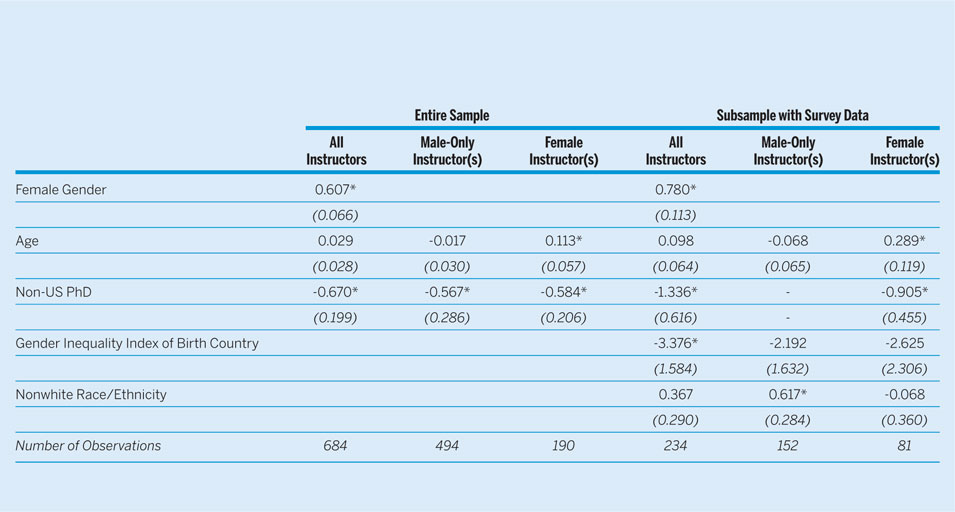

Table 1 demonstrates that instructors’ individual characteristics affect the extent to which they assign work by women. We used fractional logistic regression models to assess the roles of instructors’ gender, race, age, and national origin, as well as subfield and syllabus year, in predicting the proportion of readings on a syllabus with female first or solo authors. The variables of race and national origin were included in a separate set of models because they were available only for instructors for whom we had survey data.

Instructors’ individual characteristics predict how frequently they assign female-authored readings. Older female instructors assign more female first-authored readings, whereas white male instructors (irrespective of age) assign fewer.

Table 1 Instructor Characteristics as Determinants of Proportion of Readings with Female-First or Only Author(s)

Notes: Results are from fractional logistic regression models. Unit of analysis is the syllabus. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Models also control for year of course and subfield/topic of syllabus. Coefficients are statistically significant at *p<0.05.

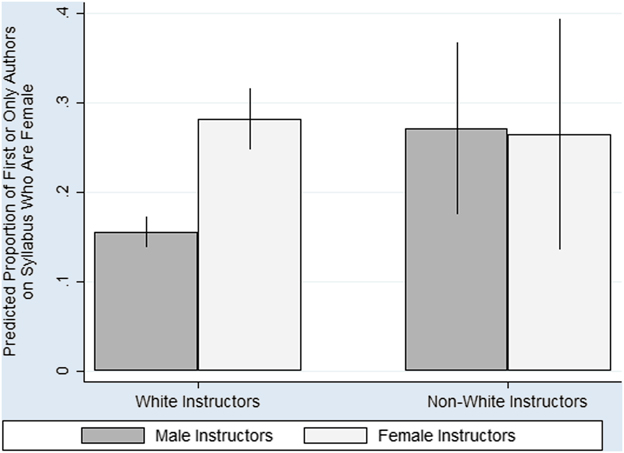

Consistent with hypothesis 2, female instructors assign more female-authored readings. Holding all variables at their observed values, 15.4% of readings assigned by male instructors are predicted to have female-first or solo authors, contrasted with 24.4% of readings assigned by female or mixed-gender instructors.Footnote 8 Moreover, although the proportion of readings with female-first authors rises as a function of publication year, the gap between male and female instructors is not closing over time (see online SI: Results). In our examination of readings authored between 2012 and 2017, 35.0% of works assigned by female instructors were female-authored and 21.8% of those assigned by male instructors were female-authored. However, table 1 and figure 2 indicate that an instructor’s race conditions the effect of gender. Race was statistically significant among male instructors, whereas gender disparities in assigning work by women were observed only among white instructors. Nonwhite male instructors assign female-authored work at rates that are indistinguishable from those of female instructors (both white and nonwhite).

Figure 2 Instructor Gender and Race Jointly Predict the Rate of Assigning Female-Authored Readings

Notes: Unit of analysis is the syllabus (N=234: n(WM)=146, n(NWM)=7, n(WF)=145, n(NWF)=6). Predicted proportions from analysis in table 2. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (calculated from robust standard errors).

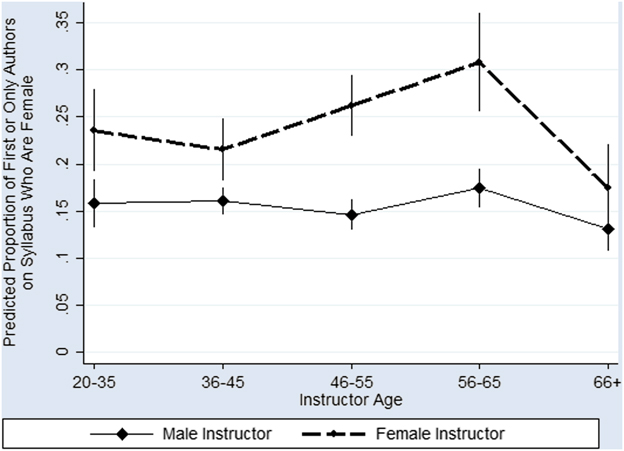

Interestingly, table 1 suggests that an instructor’s age matters among women but not men. Supporting hypothesis 3, figure 3 shows that older female instructors tend to assign female-authored readings more frequently than younger women, with a decrease after age 65. By contrast, men—irrespective of age—infrequently assign readings with female-first authors. The size of the gender gap in assigning female-authored readings thus varies by age group.

Figure 3 Instructor Gender and Age Predict Rate of Assigning Female-Authored Readings

Notes: Unit of analysis is the syllabus (N=746: n(M,20-35)=67, n(M,36-45)=177, n(M,46-55)=145, n(M,56-65)=94, n(M,66+)=53, n(F,20-35)=28, n(F,36-45)=84, n(F,46-55)=52, n(F,56-65)=38, n(F,66+)=8). Predicted proportions are from analysis per table 2. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (calculated from robust standard errors).

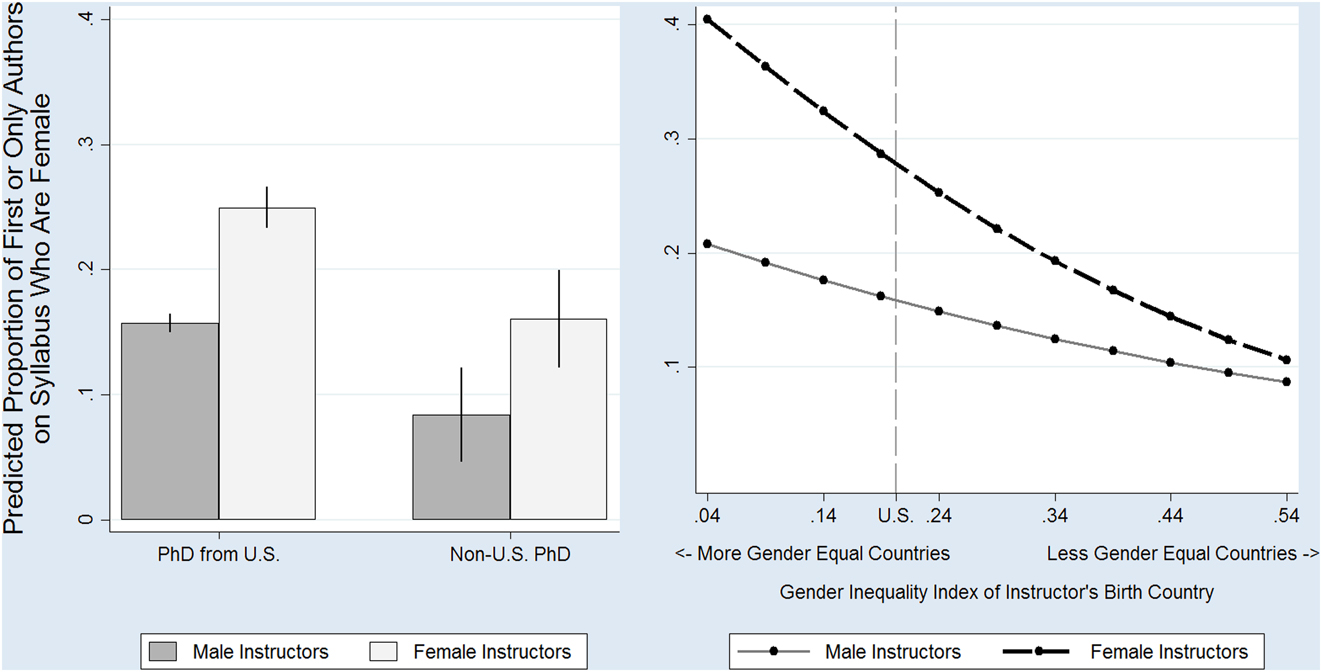

Finally, in support of hypothesis 4, we found that an instructor’s national origin matters. The right panel of figure 4 shows that men and women born in countries that are less gender equal, according to the United Nations (UN), assign fewer readings authored by women (UN Development Programme 2017). The predicted proportion of assigned work first-authored by women decreases from 0.399 for women born in the most gender-equal country in our data to 0.102 for women born in the least gender-equal country. Among male instructors, the predicted proportion decreases from 0.210 to 0.078. The left panel of figure 4 shows that both men and women trained outside of the United States assign fewer female-authored readings than their counterparts trained in the United States. Note that in our dataset, all instructors with PhDs from countries other than the United States were trained in wealthy Western countries—most prominently, the United Kingdom (see online SI: Methods).

Figure 4 National Origin and Country of PhD Predict Rate of Assigning Work Authored by Women

Notes: Unit of analysis is the syllabus (left panel N=665; right panel: N=225). Predicted proportions are from analysis per table 2. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (calculated from robust standard errors).

CONCLUSION

Women’s research is underrepresented not only in publications and article citations but also in graduate syllabi. Instructors’ individual characteristics predict how frequently they assign female-authored readings. Older female instructors assign more female first-authored readings, whereas white male instructors (irrespective of age) assign fewer. We also found that instructors from more gender-equal countries assign more female-authored work. These findings are robust to calculating the dependent variable based on all authors (not only first and solo authors) and to analysis using hierarchical models rather than fractional logistic regression models.

Our research contributes to empirical research on gender diversity in political science by introducing the original GRADS dataset. Future studies can use GRADS to code other author characteristics, such as examining the representation of people of color. More broadly, we call for greater scholarly attention to graduate training in research on diversity in academia. In particular, the consequences of gender representation in syllabi deserve further research. The visible presence of women in a career can influence other women’s attitudes toward that profession; likewise, underrepresentation in syllabi can affect female graduate student retention rates. Additionally, male and female students who rarely see women’s research may become less likely to cite women, thereby developing or reinforcing gender biases related to the quality of women’s research. Improving understanding of these early influences can help to stem leaks in the academic pipeline.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001239.

APPENDIX

Appendix Table 1 Summary Statistics: GRADS Full Sample versus APSA Data