After the Civil Rights Movement, scholars sought to explain the gap between white Americans’ principled backing of racial egalitarianism and their dismal support of policies to bring those values to fruition. Researchers noted that due to massive political and social transformations, a subtle form of racism had evolved. Among the several theories and measures that sought to capture this “new” racism, racial resentment (RR) has become the most prominent, becoming the key way that political scientists have measured and explained whites’ racial attitudes in the past four decades (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981). Although RR has been incredibly predictive of whites’ political attitudes and preferences, debates around it have “hindered the advancement of research on white racial policy attitudes” (Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005, 168). Indeed, the reliance on this measure has led political scientists to become accustomed to a myopic, static, and unidimensional understanding of white Americans’ racial attitudes.

This article highlights the idea that as the US political, economic, social, and demographic landscape evolves, so also must our measures of racial attitudes (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017). Relying on an array of contributions across the social sciences—including psychology, sociology, and critical race theory—we provide a more comprehensive structural mapping of whites’ racial attitudes and introduce a parsimonious measure of a multidimensional construct. As we show herein, the FIRE battery captures not only racial f ear, acknowledgment of i nstitutional r acism, and racial e mpathy, it also meets the criteria of a good measure, provides important information about the mechanisms that shape whites’ sentiments, and—in some cases—is as (or more) predictive than RR.

THE EVOLUTION AND COMPOSITION OF RACIAL ATTITUDES

Moving beyond the ongoing debate about whether RR measures symbolic attitudes towards blacks rather than ideological stances (Carmines, Sniderman, and Easter Reference Carmines, Sniderman and Easter2011; DeSante Reference DeSante2013), we highlight the fact that the multi-decade reliance on one measure reveals two things about the way racial attitudes are understood by political scientists. First, the persistent employment of this measure implies that racial attitudes are static even though we know that their nature and role evolve over time (Schuman et al. Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997). The development of RR was inspired by the shift in whites’ racial sentiments from being rooted in biological racism to a more subtle form of racial animus (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981).

Other scholars have pointed out that we are likely to see acceptable expressions and rationales for persistent racial inequality shift in response to major political, social, economic, and demographic transformations (DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2020a; Reference DeSante and Smith2020b). Furthermore, a consensus has emerged that “colorblind racism” is America’s current dominant racial ideology. Although having a similar effect as previous forms of racism, colorblind racism explains persistent racial disparities by relying on race-neutral ideological frames, including abstract liberalism, cultural and class differences, and the suggestion that some disparities are simply natural (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2017).

Second, our reliance on RR reflects an assumption that “racial attitudes” is synonymous with latent racial prejudice, animosity, and one type of affect (i.e., resentment), all of which collapse onto a single dimension. Research reveals that racial attitudes have both cognitive and affective components; however, most scholarship tends to focus only on the former. This narrow conceptualization disregards a scholarship that posits that racial attitudes are composed of a constellation of emotions, including anger, apathy, guilt, fear, and empathy (Banks and Valentino Reference Banks and Valentino2012; Chudy Reference ChudyForthcoming). Serious consideration of a broader range of racially related attitudes is likely to produce a far more comprehensive depiction of white Americans’ reference and orientation toward “racialized” targets (e.g., candidates, groups, and policies).

STEPS TOWARD A NEW MEASURE

We take several steps to produce a new, parsimonious measure that not only passes tests for face, convergent, predictive, and discriminant validity but also speaks to dominant narratives of racial inequality and taps into both cognitive and affective components of racial attitudes.Footnote 1 First, we consider an array of previously verified and validated survey measures that mirror socially acceptable expressions of a broad scope of racialized sentiments. Second, we map the structure of whites’ racial attitudes using factor analysis that uncovers two higher dimensions. Third, we discuss which subset of questions most parsimoniously represents the map. Fourth, we test the measure’s validity.

We take several steps to produce a new, parsimonious measure that not only passes tests for face, convergent, predictive, and discriminant validity but also speaks to dominant narratives of racial inequality and taps into both cognitive and affective components of racial attitudes.

First, we analyzed four existing measures of contemporary racial attitudes. To tap into the dominant US racial ideology, we used the Colorblind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS). This scale assesses three cognitive aspects of colorblind racial attitudes: awareness of white racial privilege, acknowledgment of institutional racism, and attentiveness to blatant racism (Neville et al. Reference Neville, Lilly, Durham, Lee and Browne2000). Second, we tapped into quasi-emotional or affective components of racial attitudes using the Psycho-Social Costs of Racism to Whites (PCRW) scale (Spanierman and Heppner Reference Spanierman and Heppner2004). Whereas CoBRAS is concerned with awareness of racial disparities and privilege, the items that compose the three subscales of the PCRW ascertain how whites feel about this reality: the first subscale measures whites’ “empathetic reactions toward racism”; the second captures the extent to which respondents feel “white guilt”; and the third measures fear toward members of other racial groups. These questions address the growing scholarship regarding the increasing racial consciousness that whites are experiencing as US demographics shift (Jardina Reference Jardina2019).

Despite the many critiques put forward about RR, compelling research shows that it measures a cohesive ideology. We need not throw out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. As such, we considered and incorporated the contributions of the scale along with the Wilson and Davis (Reference Wilson and Davis2011, 121) Explicit Racial Resentment (EXR) scale. They note that their questions “mainly differ from past resentment measures in their explicit connection between the source of the resentful feelings and the targeted racial group.”

In total, these measures individually seek to describe and measure a particular aspect of whites’ racial attitudes. Using statistical methods, we allowed the scales to interact in order to construct a more nuanced map of contemporary racial attitudes. In doing so, we expected to uncover a two-dimensional construct, in which one dimension is largely related to what Banks and Valentino (Reference Banks and Valentino2012) referred to as “emotional substrates” and the other is composed of the more cognitive components of racial attitudes.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

The best way to ascertain how these measures work together was to ask a large number of respondents all of the questions posed by these scales. Through this process, we could verify the structure of each construct. More important, we could leverage this large collection of questions to construct a structural map of whites’ racial attitudes. We also could visualize not only which attitudes are held and how strongly but also which clusters of attitudes were correlated with one another.

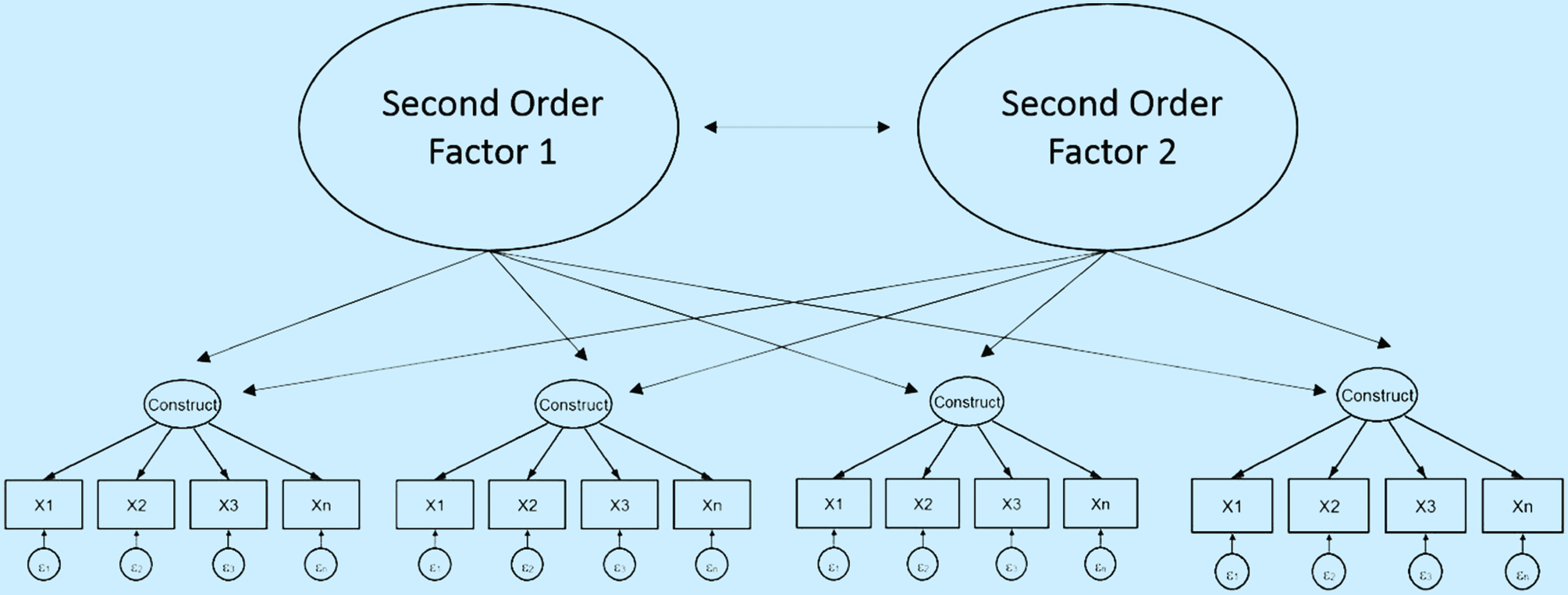

For our initial analyses, we relied on a nationally representative sample of 1,000 respondents, of whom 743 identified as white, from the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). We asked respondents all 45 questions that comprise the four racial-attitudes batteries (i.e., RR, EXR, CoBRAS, and PCRW), as well as a few questions to evaluate their political ideology to parse out the difference between conservative ideology and racial attitudes. Together, these questions compose eight validated measures.Footnote 2 Then, to determine whether our hypothesized dimensions—cognitive and affective—undergird the landscape of whites’ racial attitudes, we fit a second-order confirmatory factor-analytic model using the raw survey data (figure 1). This analysis simultaneously estimated factor loadings for each of the eight first-order factors and also estimated how those factors relate to the two hypothesized higher-order dimensions.

Figure 1 A Second-Order Latent Factor Model

These data showed promising results and confirmed that whites’ racial attitudes fall along two dimensions: a cognitive component and an emotive component (table 1). The items that loaded onto the first higher-order factor include RR, white guilt, conservative ideology, and the three subscales of the CoBRAS. The second dimension was anchored at one end by fear of other races and on the other end by empathetic reactions to racism. In terms of the traditional measures of model fit, a second-order factor analysis fit the data well: the ratio of chi-squared to degrees of freedom was less than 2 (1.64); the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.97; the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) was 0.96; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than 0.04. The second-order factor loadings, shown in table 1, were all significantly different from zero at conventional levels.Footnote 3

Table 1 Higher-Order Factor Loadings

In the map of this construct, illustrated in figure 2, higher scores relate to more positive attitudes toward racial minorities, a higher level of empathy for other racial groups, and an increased awareness of America’s racial reality. That is, respondents who scored higher on factor 1 are more aware of blatant and institutional racism, less racially resentful, less ideologically conservative, and more likely to express white guilt. On reflection, factor 1 consists of items that relate to white respondents’ understanding and awareness of racism and the racial privilege that whites enjoy in America; indeed, even the measure of “guilt” is predicated on the acknowledgment of racial privilege. This factor may indicate how knowledgeable an individual is regarding the racial status quo. Consequently, we deemed this as the more “cognitive” dimension.

Figure 2 Two Dimensions of Whites’ Racial Attitudes

In contrast, the second dimension loaded most strongly on the PCRW subscales related to racial fear and empathy. Respondents who scored higher on this factor have greater empathy toward racial minorities and are generally less fearful of other racial groups. Therefore, we labeled this the “affective” dimension. Graphically, these loadings appear as shown in figure 2, with those first-order factors on the negative side of the x-axis purposely fanned out for ease of reading. The two factors are only slightly correlated (r=0.20) and, when combined, they explain between 60% and 90% of the variance in the first-order factors.

A PARSIMONIOUS MEASURE

Asking respondents to answer almost 50 questions is neither practical nor necessary. To provide researchers with a “short form” for these two dimensions of racial attitudes, we conducted a series of computational tests to determine which smaller subset of items would explain the most variance in our two second-order dimensions.Footnote 4 After this computational procedure, the four items that appeared as the best questions to capture whites’ underlying racial attitudes were the following Likert items (ranging from strongly disagree to strong agree):

1. I am fearful of people of other races.

2. White people in the US have certain advantages because of the color of their skin.

3. Racial problems in the US are rare, isolated situations.

4. I am angry that racism exists.

These four items compose what we call the FIRE battery (FIRE is an acronym for f ear, acknowledgment of i nstitutional r acism, and racial e mpathy). It is critical to note that the four items should not be summed into a single scale for two reasons. First, it is antithetical to their derivation and, second, because we expect distinct aspects of the battery to be theoretically linked to different outcomes. Although a single additive scale may seem safer to use in terms of reliability, the next section highlights how the FIRE battery allows researchers to pinpoint the effects of the many components of whites’ racial sentiments on outcomes of interests.

These four items compose what we call the FIRE battery (FIRE is an acronym for f ear, acknowledgment of i nstitutional r acism, and racial e mpathy).

TESTS OF VALIDITY

As mentioned previously, a good measure should meet tests of convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity. We illustrate the use and usefulness of the FIRE battery by relying on data from the 2016 CCES Common Content and illuminate the validity of the measure through tests on presidential vote choice and attitudes about welfare spending. The CCES surveyed more than 60,000 Americans during the 2016 presidential election cycle; 750 answered both the FIRE battery and the RR items.

One question still being debated is whether Trump’s 2016 election was made possible, in part, by racism—beyond mere prejudice, the term often is used to refer to the racial fear of nonwhites and perceptions that whites’ group status is declining. We first reviewed the mean of the four FIRE items among people in four categories to ascertain the attitudes of voters by candidate choice: (1) those who voted for a Democrat in the primaries; (2) those who voted for a Republican other than Trump in the primaries; (3) those who voted for Trump in the primaries; and (4) voters who voted in the Democratic Primary and then voted for Trump in the general election. Figure 3 shows the means and 95% confidence intervals for these four questions.Footnote 5

Figure 3 2016 (Primary) Vote Choice and FIRE

Figure 3 demonstrates that those who voted for Democrats in the primaries are more likely to recognize institutional racism and foster racial empathy than other voters. Moreover, these measures reveal a cleavage within the GOP and speak to the underlying sentiments of Democratic–Trump “defectors.” In comparison to other Republicans, Trump supporters reported being significantly more racially fearful, less likely to acknowledge white privilege, and not as angered by racism. However, they were more likely to recognize racial problems. The FIRE measures moved in the direction that we expected and allowed us to address specific aspects of racial attitudes across and within parties.

Traditional multivariate analyses provided additional evidence for the necessity of considering this new measure. Table 2 reports a series of logistic regressions that predicted voting for Trump in the general election. The table compares the predictive role and power of FIRE to RR.

Table 2 Predicting the 2016 Presidential Vote

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Unless parenthetically indicated, all variables run from 0 to 1. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Again, the results were promising for this endeavor. Even controlling for standard demographics, each component of the FIRE battery was significantly related to supporting Trump, which is similar to Hooghe and Dassonneville’s (Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018) findings. The second and third models allowed a comparison of FIRE and RR, revealing that racialized fear was one of the strongest predictors of preferring Trump to Clinton. More important, when the FIRE variables and RR were simultaneously included (model 3), the effect of RR diminishes by more than 50% and no longer meets the conventional level for statistical significance (p = 0.11).

Next, we examined whether and the extent to which respondents believe their state legislature should increase or decrease welfare spending. Although racial fear may have been stoked in the 2016 election, we do not believe that it shaped attitudes about welfare spending. However, because the policy is racialized, we expected other components of racial attitudes to influence responses. We followed an almost identical modeling strategy as before; however, because we treated the five-point spending variable as continuous, we used OLS. The estimates are presented in table 3.

Table 3 Predicting Support for Welfare Spending

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Unless parenthetically indicated, all variables run from 0 to 1. †p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

The first model in table 3 reveals that every item except racialized fear was strongly related to opinions on welfare spending. These coefficients were attenuated when we added the RR battery (model 3). Nevertheless, the importance of recognizing that whites have advantage and care enough to be angered by racism illustrates the predictive value of FIRE, even when controlling for respondents’ RR score.

These results show the predictive power of these two dimensions of racial attitudes. The fear/empathy dimension differentiated those who voted for Trump from members of the GOP who preferred another candidate. Trump’s supporters were more fearful of other races, the least angered about racism, and least likely to agree that whites have advantages based on the color of their skin. Our examination of a racialized policy reveals how the dimensions work in tandem to predict policy positions. Those who are most supportive of welfare are those whites who recognize that they have advantages and are angered by racial inequality. Across these political domains, we can pinpoint the component(s) of racial attitudes that influence whites’ preferences. We found similar support for FIRE with issues such as interracial marriage and whites’ sense of urgency around racial inequality (see the online appendix).

DISCUSSION

Given that racial language and logic evolve and that racial attitudes are multidimensional, it is important that scholars develop more accurate ways to measure whites’ racial attitudes. In our effort to advance the research on these attitudes, we examined racial sentiments beyond resentment—including empathy, fear, guilt, and anger—and illuminated the relationship among them. In doing so, we derived a measure that meets both theoretical and technical criteria of validity. FIRE provides substantial predictive power, and it gives scholars greater nuance and leverage to describe and explain the effects of different components of whites’ racial attitudes.

FIRE provides substantial predictive power, and it gives scholars greater nuance and leverage to describe and explain the effects of different components of whites’ racial attitudes.

We do not advocate for the blind use of the FIRE battery; however, our two goals are to (1) begin a conversation within political science regarding the affective facets of racial sentiments; and (2) reinvigorate debates related to measuring racial attitudes in an America that is not only temporally distant from when Kinder and Sears (Reference Kinder and Sears1981) developed the RR scale but also culturally, politically, socially, and demographically different from that era. We admit that no measure is perfect, but all measures can be useful.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000414.