Academic conferences are important institutions for promoting new research and facilitating conversations about the field. Yet, they also are spaces where power, hierarchy, and social norms combine in ways that can facilitate identity-based discrimination, harassment, and assault. Examples of harassment at academic conferences are rife on social media (Custer Reference Custer2019; Jaschik Reference Jaschik2018). Sexual harassment is the most prominent form of harassment described in discussions of negative conference experiences, with the rise in 2017 of #MeTooFootnote 1 serving as one catalyst for sharing sexual harassment and assault experiences. Despite its predominance, sexual harassment is not the only cause for concern. Harassment or discrimination on other identity dimensions, particularly race, also have been raised as issues during academic conferences (Sutton Reference Sutton2022). A 2017 survey conducted by the American Political Science Association (APSA) found that 37% of respondentsFootnote 2 had experienced some form of negative behavior at an APSA annual meeting (Sapiro and Campbell Reference Sapiro and Campbell2018). The negative behaviors ranged from being the target of “put-downs” to being threatened for sexual contact.

One proposed solution to the conference harassment problem is a code of conduct (Favaro et al. Reference Favaro, Oester, Cigliano, Cornick, Hind, Parsons and Woodbury2016).Footnote 3 Codes of conduct (hereinafter “codes”) are written documents that outline rules for behavior at conference events. They generally are designed to limit harassing behaviors, especially harassment based on a participant’s identity. Codes also often include language about creating a supportive yet rigorous environment for academic inquiry and debate. When these codes work as intended, they can result in conferences that are more welcoming and inclusive (Favaro et al. Reference Favaro, Oester, Cigliano, Cornick, Hind, Parsons and Woodbury2016).

Political science is a particularly relevant arena in which to study the prevalence and content of codes because our field is explicitly interested in the role of power, formal rules, and informal norms in shaping human behavior. We have studied codes that apply to politicians and political bodies—for example, Collier and Raney (Reference Collier and Raney2018) and Atkinson and Mancuso (Reference Atkinson and Mancuso1985)—but we know less about how codes apply to our own behavior. Our study follows the example of Foxx et al. (Reference Foxx, Barak, Lichtenberger, Richardson, Rodgers and Williams2019), who researched the prevalence and content of codes at biology conferences in the United States and Canada. They found that 24% of conferences (46 of 195 biology conferences) had codes publicly available on their websites. Our study of 177 US-based political science and adjacent-field conferences and workshops finds that 19% (34 of 177 surveyed conferences) had a code publicly available on their website. If we limit our sample strictly to political science conferences and workshops, excluding events from adjacent fields, the percentage with codes decreased to 17%, or a total of 25 conferences of 146 (Lu and Webb Williams Reference Lu and Williams2024).

Our study of 177 US-based political science and adjacent-field conferences and workshops finds that 19% (34 of 177 surveyed conferences) had a code publicly available on their website.

Foxx et al. (Reference Foxx, Barak, Lichtenberger, Richardson, Rodgers and Williams2019) demonstrated that the content of biology codes varies widely, and we find that the same is true in political science. Importantly, differences in code content can affect their effectiveness. For example, prior research demonstrates that the content matters in determining whether code violations are reported (Nitsch, Baetz, and Hughes Reference Nitsch, Baetz and Hughes2005). As discussed in the next section, the effectiveness of a code is shaped, at least in part, by three main dimensions of content: (1) definitions, or whether information is included about what constitutes code violations; (2) reporting, by which we mean whether and how the code describes ways of reporting code violations; and (3) enforcement/adjudication, or whether and how the code explains what happens after potential code violations are reported. In terms of the first effectiveness dimension, 85% of the analyzed codes contained some type of information about what constitutes a code violation, either by explicitly defining discrimination/harassment or including a list of prohibited behaviors. Regarding the second dimension, 74% of codes contained at least one mechanism for reporting violations; however, only 6% had a reporting mechanism that was external to the organization. Regarding the third dimension, we found that 62% of codes contained at least some information about the process of investigating possible violations, and 74% of codes listed consequences for violating the code.

74% of codes contained at least one mechanism for reporting violations; however, only 6% had a reporting mechanism that was external to the organization.

We next explain why these three dimensions are important for an effective code. We then discuss why certain types of conferences and conference-organizing groupsFootnote 4 may be more likely to have a code. We suggest that the prevalence of codes can be explained by features such as conference size and the presence of women or relevant committees in conference leadership. We then describe our data-collection and analysis procedures and present descriptive results on the prevalence and content of codes. We also generate aggregate “scorecard” measures to report and compare the overall quality of codes based on our three effectiveness dimensions. The article concludes with a summary and suggestions for future research as well as how our discipline can improve codes of conduct.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD CODE OF CONDUCT?

The purpose of a code is twofold: (1) it discourages negative behavior from happening, and (2) it responds to negative behavior if it does occur. How do we know if a code achieves its purpose? Our study focuses on the content of the codes as indicators of their potential to stop harassment from occurring and to respond appropriately to harassment when it does occur. That is, we evaluated the content of the code, not conference-level outcomes. In an ideal world, we would link the policy text to changes in actual behavior. However, the first goal makes it difficult to evaluate the success of a code—it would be difficult to find evidence that someone intended to use a conference to harass others but then changed their mind after reading the code.Footnote 5 If a code is successful in its second goal by encouraging reporting, its adoption may lead to an increase in the number of reported incidents. This could make it appear that the number of incidents has increased (i.e., a failure of the code) when, in fact, it is more reporting of the same number of incidents (i.e., a success of the code). We also are limited by a lack of data on incidents and outcomes because those data are held by conference organizations, which rightly are concerned about privacy and confidentiality.

What can we learn, then, about code effectiveness solely from code content? In general, we know little about whether written policies translate into actual decreases in harassment. In a recent review of the literature on sexual harassment in higher education, Bondestam and Lundqvist (Reference Bondestam and Lundqvist2020, 406) found that “there is almost no evidence-based research on the actual effects of policies on, for example, decreasing prevalence of sexual harassment.” As Stubaus (Reference Stubaus2023, 66) wrote: “More research is needed on whether formal sanctions are effective in preventing repeat harassment and, if they are, which sanctions are most effective….” Despite this lack of research, we can extrapolate a framework on what theoretically might make codes more effective in terms of both preventing and responding to harassment by reviewing best practices from nonacademic sectors.Footnote 6 The US Equal Opportunity Commission (n.d.), for example, lists steps for preventing harassment in small businesses that include informing employees about harassment, identifying reporting contacts, and efficiently investigating complaints. The International Labour Organization (ILO) suggests codes as one form of a policy document to reduce harassment (2022, 30). The ILO (2022, 28) recommends that policies to reduce harassment include definitions and examples, information on how to report complaints, and provisions for fair investigations that protect confidentiality.

In addition to recommendations for policies designed to limit harassment, we consider recommendations for how to design an effective code, even if that code is applied to a non-harassment domain. For example, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) literature often addresses the content and effectiveness of codes in changing business behaviors. To compare the content of CSR codes in international franchising, Preble and Hoffman (Reference Preble and Hoffman1999, 247–49) searched for the presence of ethical statements (equivalent to our “definitions” dimension) and enforcement mechanisms (equivalent to our “enforcement/adjudication” dimension). Another study of CSR code content noted that codes need to specify how to report misbehavior to a “competent body” (Béthoux, Didry, and Mias Reference Béthoux, Didry and Mias2007, 84). Researchers also study how CSR code users (i.e., employees) perceive elements of effective codes. Employees express the importance of language that requires code violations reporting, mechanisms that protect anonymity, and consistent enforcement (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2004, 334). When managers are asked how to increase the “teeth” of codes to reduce discrimination in the workplace, they contend that enforced sanctions result in more effective codes (Petersen and Krings Reference Petersen and Krings2009).

As further evidence of what makes an effective code, we can review critiques of codes—a “good” code should have in it what is lacking in “bad” codes. For example, consider the recent adoption of a code of conduct by the US Supreme Court. Many experts have criticized the “lack of an enforcement mechanism” in the document (see, e.g., Liptak Reference Liptak2023). A similar argument was made by Spar (Reference Spar1998) regarding monitoring mechanisms in corporate codes. These critiques suggest that enforcement is a crucial component in an effective code.

The common elements from these sources indicate that preventing harassment with codes involves informing and responding. Conference attendees must know which behaviors are prohibited; they must have an effective means of reporting troubling behaviors; and they must know that their reporting will lead to consequences. In other words, for a code to be effective in curbing discrimination and harassment, it should (1) define what constitutes discrimination and harassment; (2) provide reporting mechanisms—ideally, mechanisms that protect confidentiality and privacy; and (3) specify how reports are adjudicated and enforced, including potential consequences of code violations. The fourth section defines and evaluates specific measures concerning these three dimensions.

WHICH TYPES OF CONFERENCES ARE MORE LIKELY TO HAVE CODES?

Which factors explain why some conferences have a code whereas others do not? In general, better-resourced conferences should be more able to invest time and energy in developing a code. In addition, the leadership composition of a conference may matter, specifically if there are more women in leadership roles or if there are other formalized means for putting harassment issues on the agenda. This section describes six potential correlates for the likelihood of having a code: conference age; size; presence of permanent staff; women in leadership roles; presence of status, professional ethics, or diversity committees; and conference mode (i.e., online or offline).

First, we considered the age of a conference, with an expectation that older, more established conferences will be more likely to have a code. Older conferences may have a larger base of resources from which to draw. They also may be more aware of the issue of harassment at conferences. For example, they may have had past scandals that prompted action. We measured the number of years that a conference has been in existence.

Second, we expected that larger conferences will be more likely to have a code. Again, the primary logic supporting this expectation is the availability of resources to develop a code. In addition to having more resources, larger conferences may have more need for a code. It is more likely that most participants in smaller conferences know, or know of, one another. These smaller conferences may rely more on informal mechanisms to mitigate harassment, such as not admitting known harassers or relying on “whisper networks” to indicate who is to be avoided. We measured the size of conferences by the number of days of their most recent conference.Footnote 7

Third, we tested whether the presence of permanent conference staff is correlated with a code. This is an extension of the logic of conference size but focuses on the financial resources of a conference. We expected that conferences with the resources to hire permanent staff also are more likely to have the resources to draft a code.

Fourth, we tested for the presence of women in leadership roles. From the publicly available documentation about the effort to address harassment in political science (e.g., Binder Reference Binder2019; Brown Reference Brown2019; Sapiro and Campbell Reference Sapiro and Campbell2018), it is clear that one driving force behind the creation of codes is individuals with a strong interest in deterring harassment at conferences. Those who work to bring the issue forward often are women; for example, in the case of APSA, a group of “senior women” wrote a letter of concern to organization leadership in 2015 (Sapiro and Campbell Reference Sapiro and Campbell2018, 5). We systematically evaluated the presence of women in leadership by researching every person listed in a leadership roleFootnote 8 to observe which pronouns were used to describe them, assuming that “she/her/hers” are used for women.Footnote 9 Of the surveyed conferences for which we could find information, 90% had at least one woman in a leadership role; the median percentage of women in leadership was 50%.Footnote 10 We used percentage of women in leadership as our measure in the quantitative analysis.

Fifth, we searched for the presence of a relevant status, professional ethics, or diversity committee (binary measure in analyses) in the organizations holding a conference.Footnote 11 Committee work is another way that individuals can bring the issue of harassment to the conference agenda. The presence of such committees speaks to both the resources available to the conference and the directives from leadership to address these issues.

Sixth, the conference mode also may affect the prevalence of codes. Strictly online conferences may be less likely to have a code than offline conferences. Online conferences do not create opportunities for physical harassment; therefore, organizers may not see the need for a code.

We emphasize that these factors are not the only possible drivers for code adoption and creation. Further research into the exact details of how codes are created, maintained, and enforced is warranted to better understand how they come into existence.

CONFERENCES, CODES, AND CONTENT ANALYSIS

We compiled a list of 177 conferences and workshops from political science and adjacent fields. To be included in the study, a candidate event had to meet at least one of two main criteria as well as additional secondary criteria. First, the event could be open to submissions, meaning that presenters are not by invitation only and that we could find an online record of an open “call for proposals” or a contact link for scholars to self-nominate to present. Second, attendance at the event must have been open to all who wanted to register; this excluded, for example, departmental speaker series because attendance generally is limited to department or university members. The second criterion means that we included events with invitation-only speakers if the event was open to all attendees. Most of the included conferences met both criteria; all met the second criterion. As additional criteria, we considered only those events based in the United States, and the event had to have a website.

We searched for conferences in seven areas of political science: general, American politics, comparative politics and area studies, international relations, methodology, political theory, and regional and subgroups. The first six areas are standard subfields in political science. We used the last type, regional and subgroup conferences, to refer to either regional conferences that were open primarily to scholars based in a certain region or those that were designed for groups of scholars based on specific identities. Because of the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of our field, we also included prominent conferences from adjacent fields (e.g., sociology, economics, and history) and area studies (e.g., the African Studies Association). Table 1 lists the number of identified conferences in each area. Online appendix A contains the full list of conferences and a description of how we compiled our final list. We gathered data on the factors potentially associated with the likelihood of a code from conference websites.

Table 1 Numbers of Conferences and Workshops by Type

We searched the website of each conference for a code from the most recent gathering. To be counted as a code, the document had to contain provisions regarding behavior at conferences. Documents that counted as codes by our definition were not always officially labeled as such. Other relevant document titles included “Statement of Diversity and Inclusion,” “Professional Conduct Policy,” “Ethics Statement,” “Policy Against Harassment,” and “Conference Rules & Guidelines.”

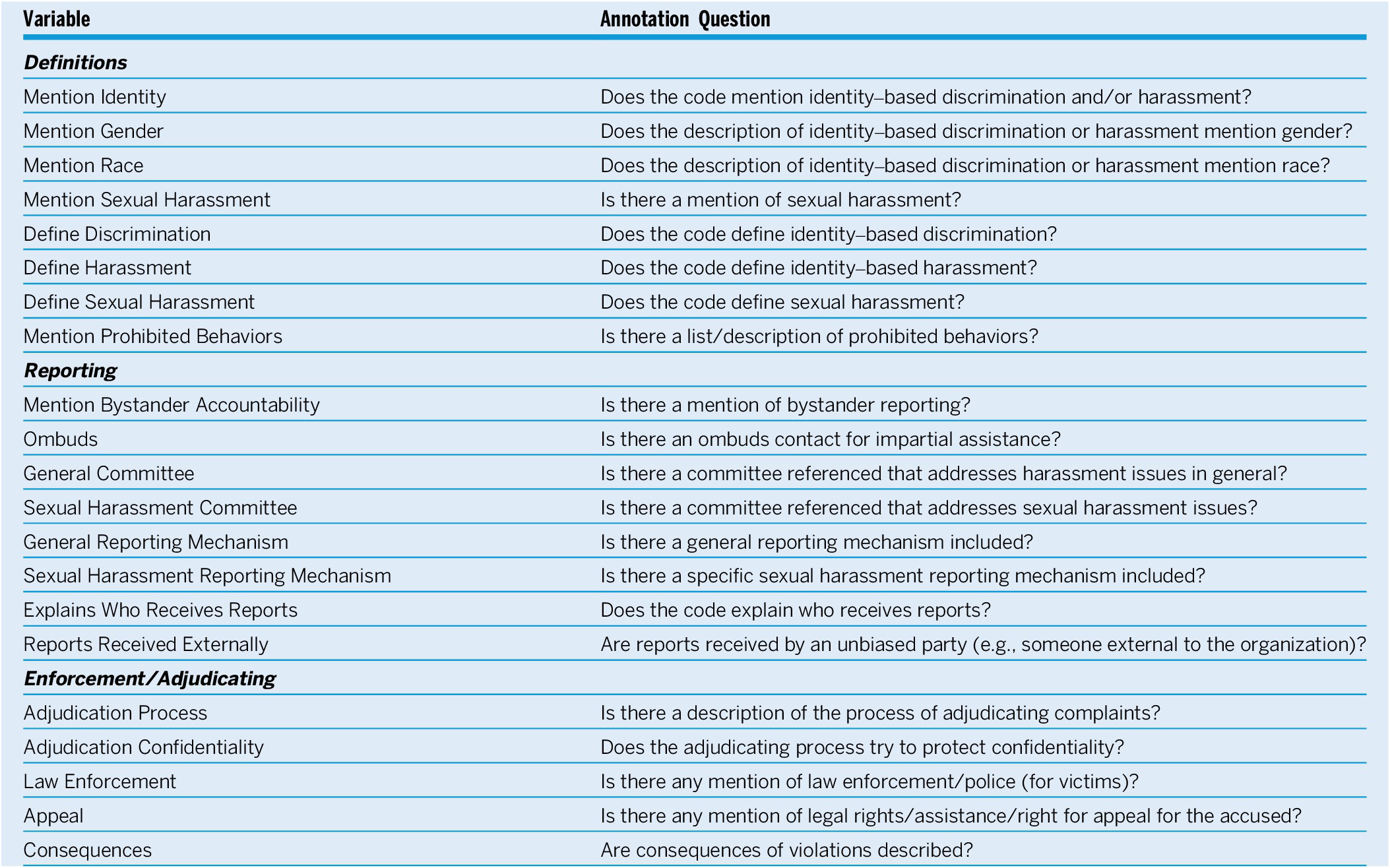

Codes, when found, were labeled manually by the two authors of this study. In the initial round of coding, the average inter-rater reliability as measured by Cohen’s Kappa was 0.63 for 21 closed-ended questions, which is in the range of a substantial yet still unsatisfying agreement between the two annotators. We therefore undertook multiple rounds of annotating and included a final correction and consensus-building step. Ultimately, we reached 100% agreement on all of the annotations (see online appendix B for a full description of the labeling process, including example language from codes that met our definitions). The content we labeled for is listed in table 2.

Table 2 Content Variables and Annotation Questions

RESULTS

Our first result was the prevalence of codes. We found that 34 of 177 surveyed conferences (19%) had a code.Footnote 12 Limiting the events to strictly political science conferences and workshops, there were 25 of 146 conferences with a code (17%). The distribution of codes by subfield is shown in online appendix C, figure 3.

Although we treated each conference and code independently, there was strong preliminary evidence of diffusion effects in the enactment of a code and in the language included in it. We found that 44% of codes either explicitly stated that they were modeled on previous codes or were implicitly modeled on other codes (e.g., similar formatting, structure, and language). Results from an automated analysis of text similarly indicated that the language of APSA’s code has been reused and adapted frequently.Footnote 13 This supports the theoretical narrative of resources impacting the adoption of a code—the larger conferences have the membership and staff to advocate for the creation of a code. Smaller conferences with fewer resources can adopt a code, but it becomes easier when there is a model to follow.

Online appendix D, table 6, presents the complete results from bivariate ordinary least squares regressions of the six factors potentially associated with code prevalence: conference age, permanent staff, size/length, mode (online/offline), female leadership, and relevant status/ethics committees.Footnote 14 For analysis, we divided the age of conferences into three categories: more than 50 years, 25 to 50 years, and less than 25 years (see appendix C, figure 3, for the distribution). Of the 26 conferences that had a history of more than 50 years, an average of 65% were predicted to draft a code. In contrast, the probabilities decreased significantly for conferences with a shorter history. Only approximately 14% of conferences that were less than 25 years old were predicted to have a code.

We also found that the longer a conference has been held, the higher the probability of it having a code: one additional day increased the probability by 17%. Regarding the final measure of resources, conferences with permanent staff were 42% more likely to have a code than those without permanent staff. In terms of mode, 23% of the offline conferences had a code versus only 10% of online or hybrid conferences.

Regarding gender in leadership, conference leadership is, on average, 50% female. With such a high proportion of women in leadership, there was little variability to associate with code prevalence: we did not find significant differences between the existence of a code and a higher percentage of women in leadership. However, we did find a significant association between the presence of a status, professional ethics, or diversity committee and a code. Conferences with at least one of these relevant committees were 30% more likely to adopt a code of conduct.

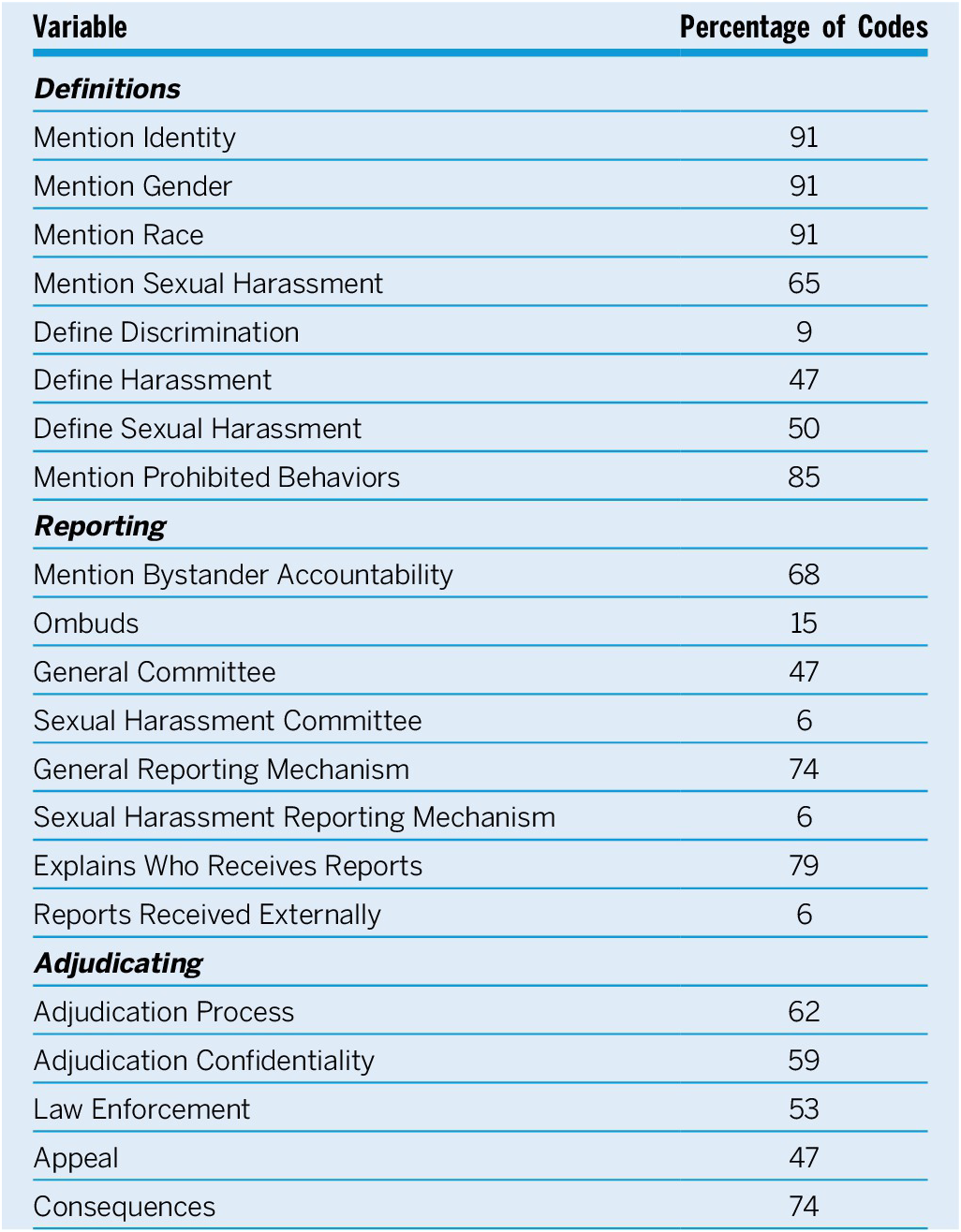

The main results from the content analysis are presented in table 3, which lists the percentage of codes that had each element. On definitions, it is noteworthy that the surveyed codes did well at listing identities (see online appendix C, figure 5, for a word cloud of these) but did less well at explicitly defining negative behaviors. Less than 50% of the codes defined harassment and only 9% defined discrimination. Regarding reporting, most codes (more than 70%) had a means of reporting but few (only 6%) had a way to report to external channels. Online appendix C, table 4, lists the counts of specific reporting mechanisms (e.g., an email address for reports and speaking to conference staff). Only 15% of the codes mentioned an ombudsperson. Finally, regarding adjudicating, most codes (74%) mentioned the consequences of violations and approximately 50% mentioned law enforcement, confidentiality, or appeals.

Table 3 Summary of Code Findings

Next, we summarized the overall quality of codes by tallying how many of the elements identified in table 2 were present in each code. Regarding the definitions dimension, we specified six binary checkpoints based on mentions and definitions of discrimination and harassment (see online appendix E, table 8, for details about these factors). There were seven checkpoints for reporting and five for enforcement. Thus, the highest possible score for a code based on our benchmarks was 18. Figure 1 shows that 23 of 34 codes had scores higher than 9.5, which was the mean of the total score. In other words, on average, approximately 30% of the codes missed half of the components that we identified as important for a “good” code. Twelve codes earned a score of 13 or 14, which suggested that many codes contained many of the elements we identified. However, none of the codes had a perfect score. The highest score of the surveyed codes, achieved by one conference code, was 16.Footnote 15

Figure 1 Distribution of Combined Content Scores

The dashed line is the mean.

The distribution of codes by each dimension listed in figure 2 demonstrates that the codes did well on definitions: 71% were above or equal to three of six possible points. For reporting and enforcement, there were major divides: seven codes scored a zero on reporting and nine codes scored a zero on enforcement/adjudication. Most codes scored four of seven points on reporting, which means that there were at least some mechanisms in place for victims or bystanders to report incidents. The enforcement scores were significantly divided. Many codes (13 of 34) had either the full set of enforcement elements or none of them.

Figure 2 Distribution of Content Scores on Three Dimensions

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The increase of codes at political science conferences demonstrates that there are many who want to make our field more welcoming for all. Although codes are not a panacea to cure all academic conferences ills, they are a step that organizers have taken to reduce discrimination and harassment. Approximately 19% of the surveyed political science conferences had a code. We found evidence that larger, better-resourced, offline conferences are more likely to have a code. We also found that conferences with relevant committees are more likely to have a code. We found no association between the prevalence of women in leadership and the presence of a code—perhaps because most of the conferences have a high proportion of women in leadership. We note that these descriptive findings are from bivariate analyses without accounting for likely confounding among factors.

The increase of codes at political science conferences demonstrates that there are many who want to make our field more welcoming for all.

Prior literature suggests that more effective codes will contain definitions, information about reporting channels, and procedures for enforcement. We found variability in the content of political science codes on these dimensions. The analyzed codes did well in identifying prohibited behaviors but they did less well on reporting mechanisms and procedures for enforcement. We found that few codes had a way to report complaints to bodies external to the conference association. Few codes also had a truly external ombudsperson who could provide information and advice to potential complainants.

One theme that emerged from our study in terms of both code prevalence and content is the role of resources in creating and enforcing codes. Ending conference harassment will require time, energy, and expense, whether via a code or through other mechanisms. Maintaining external reporting channels, hiring ombudspersons, and staffing committees are not inexpensive tasks. Relying on volunteer labor has a significant opportunity cost for those who serve. Our general findings and the theme of resources lead us to make the following suggestions to those conferences that are considering a code of conduct:

-

• Draft codes to include clear definitions, reporting, and enforcement/adjudicating.

-

• Use prior examples as a model for new codes, but first determine whether their provisions fit what the conference is willing or able to do.

-

• Ensure that codes are backed by sufficient resources for enforcement and maintenance.

-

• Create standing status, ethics, and/or diversity committees to reevaluate, modify, and enforce codes of conduct.

As a discipline, there are ways that large conference organizations and wealthier parties can support measures to improve our understanding of what works and our ability to provide it. We offer the following suggestions:

-

• Organizations should be transparent about how codes of conduct are created and implemented because examples from one organization shape developments in others.

-

• Large, well-established conferences should consider how they can use their leadership position to improve codes by sponsoring research and workshops to share information among conference organizers.

-

• We should consider pooling resources among conferences or across the discipline to maintain external ombudspersons, reporting channels, and enforcement procedures.

In addition to these normative suggestions, this study has prompted important questions for future research. We want to see more research on actual code effectiveness. In the CSR literature, research has found a significant relationship between code quality and businesses’ organizational cultures (Erwin Reference Erwin2011). Does the same hold for conference codes? Researching how a code of conduct can change behavior at conferences may involve partnering with organizations to determine whether enacting a code changes reporting and/or incidents of harassment. Qualitative work on the history of how codes are enacted and how they work in practice would complement our quantitative findings on the diffusion of codes among organizations. Finally, there are many other factors that could explain the prevalence of codes or the prevalence of certain elements in them. Future work could consider the role of scandal, for example, or the role of non-white conference leadership. Our study provides an important first step in understanding the prevalence and content of codes of conduct in political science.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096524000179.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Foxx et al. (Reference Foxx, Barak, Lichtenberger, Richardson, Rodgers and Williams2019), especially Evelyn Webb Williams, for inspiring this article. We thank participants at our 2023 Midwest Political Science Association panel and the Spring 2023 Department of Political Science Student–Faculty Seminar at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign for their helpful comments and suggestions. Hyein Ko provided detailed comments on the manuscript, for which we are grateful. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers for their excellent recommendations on how to improve the article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PSS2KP.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.