The confirmation of Supreme Court justices is reserved for the United States Senate by Article II of the US Constitution. In the words of Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), “Few responsibilities we have as Senators are more important than our responsibility to advise and consent to the nominations by the President to the Supreme Court.” Footnote 1 Justice Antonin Scalia’s death touched off a political fight not resolved until procedural changes to the Senate resulted in the appointment of Neil Gorsuch more than one year later. The process of filling this vacancy is historically important for two departures from Senate norms that reflect the changing style of a younger and polarized Senate.

The need to break a filibuster on a Supreme Court nominee with a vote of 51 senators to confirm Justice Neil Gorsuch was a precedent that will change the politics of obstruction. Previously, from 1975 to April 6, 2017, Rule XXII required a vote of three-fifths of the chamber to end debate and vote on a Supreme Court confirmation. The nuclear option is an easily recognizable change in how the Senate operates, however, this new precedent was dependent on the vacancy continuing beyond the 2016 election and one party controlling both the presidency and the Senate. Footnote 2

The vacancy extended because the Senate Judiciary Committee delayed hearings for any nominee to the next presidential administration. Keeping the vacancy open until the 2016 presidential election was a way for the Senate majority to control the confirmation process. The expectation that the Senate would automatically begin with meetings and hearings was challenged by the divergent views of senators on the institution’s role in advice and consent.

At the time of the first vacancy, I was an APSA congressional fellow in the office of a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Therefore, I reflect on the landmark decision not to observe the institutionalized norm of committee hearings for Judge Merrick Garland (Collins and Ringhand Reference Collins and Ringhand2016). Given my placement in the Office of Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), I was able to observe how a former chairman supported the current chair and remained mindful of the Senate’s traditions. After the nomination the senator became the focal point of President Obama’s attempts to pressure Senate Republicans to support the nominee. What followed was an understanding of how the Constitution, Senate rules, and politics of the time all contribute to the Senate’s advice and consent power.

This article examines the Senate’s style in considering judicial nominees in relation to polarization, narrow Senate majorities, and a close contest for majority control of the chamber. The purpose is to explore the hypothesis that participation in Senate traditions of the judicial confirmation process are not universally valuable when the debate over the nominee is tightly controlled by the majority. An analysis of senator-nominee meetings in the 114th Congress identifies patterns of which senators observed the tradition of personally meeting with the Supreme Court nominee. Also, reviewing the Senate Judiciary Committee’s meetings from 1981 to 2016 shows when the norm of institutionalized hearings began to decline for pending nominees to lower federal courts. By considering the Garland nomination within the context of the Senate’s recent history, we find Senate norms that promote deliberation decline when senators expect intense disagreement.

SENATE NORMS AND SEPARATION OF POWERS

From 1955 to 2016, Supreme Court confirmation votes were traditionally preceded by senator-nominee meetings and hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Meetings provide private and courteous exchanges, while hearings provide broader public scrutiny. These traditions are a hallmark of deliberation of high profile confirmations in the Senate. However, both norms became strained in 2016 as only 53 senators met with the nominee and the committee did not hold hearings for the first time since 1945.

Intense party competition and polarization encourages senators to constrain the president’s ability to make appointments (Binder and Maltzman Reference Binder and Maltzman2009). When lawmakers use the confirmation process to gain leverage over the executive, occasionally the regular procedures for deliberation can be an obstacle instead of a tool. A decline in deliberation occurs most often when the majority suspects the process may be used to politicize the reputation of a nominee for a political goal. One consequence of less information is that senators define nominees by the policy positions of the executive making the nomination. To understand why Merrick Garland did not receive a hearing with the Senate Judiciary Committee I discuss the diverse incentives for senators of the majority party.

When lawmakers use the confirmation process to gain leverage over the executive, occasionally the regular procedures for deliberation can be an obstacle instead of a tool.

The timing of the vacancy created a challenge for President Obama to quickly appoint a new Supreme Court justice. During divided government, vacancies often last longer, especially when the Senate majority is unified and is incentivized to be uncooperative (Shipan and Shannon Reference Shipan and Shannon2003). Still, President Obama had reason to believe a nominee could receive a hearing and a vote as nominees to the Supreme Court did in 1932, 1940, 1968, and 1988. The timing of the vacancy also posed the question of whether party polarization in 2016 was great enough to alter the Senate’s norms and practice.

As President Obama proceeded in choosing a nominee, senators made 80 floor speeches (24-R, 56-D) between February 22 and March 11, 2016 about the Supreme Court vacancy. Many speeches emphasized the influence justices have on broader political issues and set clear differences between how both parties wanted to proceed. The speeches from Senate Democrats included statements from all nine members of the Senate Judiciary Committee (specialists) and 22 other Democratic senators not on the committee (generalists) to advocate the Senate consider a nominee. The broader participation among Democratic senators created a context where 61% of their speeches on the Supreme Court vacancy were made by generalists in the Senate. The greater participation of senators not on the Senate Judiciary Committee allowed members to use the confirmation battle to advertise their position on policy (Lee Reference Lee2010; Sinclair Reference Sinclair1989).

The floor speeches by Senate Republicans appeared to follow the norms of apprenticeship and specialization with 71% of the speeches made by committee members. Chairman Grassley (R-IA), Majority Whip Cornyn (R-TX), and Senator Hatch (R-UT) led most of the messaging on the floor with speeches each week. The total floor debate by Senate Republicans included statements by seven of the eleven committee members, all party leaders, as well as Senators Cotton (R-AR), Isakson (R-GA), and Lankford (R-OK) who were not members of the Judiciary Committee.

Beyond floor speeches, the influence of the Senate Judiciary Committee became more direct when all 11 Republicans on the committee signed a letter to Majority Leader McConnell (R-KY) suggesting hearings be delayed. Footnote 3 Because judicial nominations are referred directly to the committee, the position of these senators was consequential in terms of agenda control. Overriding the committee was unlikely, because whip counts suggested any vote to bring a nomination to the floor would fail.

In this early stage the deference to a committee, before President Obama made the nomination, represents the continued influence of specialization as a Senate norm. Increased participation by Senate Democrats shows the president’s party is likely to advocate for the president’s appointment power. Interestingly, the Senate also has traditions that encourage universal participation in the confirmation process for Supreme Court nominees. In the next sections, I address how senators observe the traditions of meetings and hearings for a nominee.

SENATE POLITICS IN RESPONSE TO A NOMINATION

President Obama used the Senate’s calendar to his political advantage when announcing his nomination. In the Rose Garden, President Obama said “I know that tomorrow the Senate will take a break and leave town on recess for two weeks. My earnest hope is that senators take that time to reflect on the importance of this process to our democracy…” (Obama Reference Obama2016). Before the nomination President Obama also worked behind the scenes to provide some senators with details on the pending nomination, however, the opposition was largely left in the dark. Footnote 4

It was fascinating to observe how the Senate’s workload was affected by the announcement of a nominee, especially for the committee of jurisdiction. Between January and mid-March 2016 the Senate Judiciary Committee effectively reported and passed bipartisan bills (i.e., Comprehensive Addition Recovery Act). During the week of the nomination, the committee was set to consider four lower court nominees and four bills. However, the announcement came one day before the weekly mark-up meeting and the agenda was taken over by senator statements on the Supreme Court nomination. As a result, none of the bills or nominees were dispensed with before the recess (cf. Madonna, Monogan, and Vining Reference Madonna, Monogan and Vining2016).

The potential for confusion and defections among Senate Republicans was recognizable in three occasions the following week. Senators Mark Kirk (R-IL) and Susan Collins (R-ME) advocated for committee hearings to illustrate their independence from the party. The third defection was by Senator Jerry Moran (R-KS), who told constituents “I would rather [have] you complaining to me that I voted wrong on nominating somebody than saying I’m not doing my job” (Raju Reference Raju2016). Following threats of a primary challenge from conservative organizations, Moran informed Chairman Grassley (R-IA) he opposed the confirmation. The actions of Senators Collins, Kirk, and Moran show senators experienced electoral pressures from the primary and general electorates based on their response to the nomination.

Fewer Courtesy Meetings with the Nominee

Judge Garland’s first task as a nominee was to meet with individual senators. Minority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) and Judiciary Committee ranking member Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) hosted the first two meetings on March 17, 2016. Garland went on to meet with 53 senators (43-D, 10-R) over 12 weeks. Footnote 5 Senator Angus King (I-ME) described the process as “a slow-motion hearing without the public being able to watch what is going on,” Footnote 6 which illustrates that many senators followed the traditional norms of the Senate; however, what stands out is that the factors influencing the decision to host a senator-nominee meeting were different for each senator.

The belief that committee members and senators up for election would be the first to meet with the nominee did not occur (Bowman 2016; Reid 2016). Of the 24 Senate Republicans up for reelection, only seven met with Garland. Among the 20 senators on the Judiciary Committee, only 12 met with Garland. Those 12 meetings included all of the Democrats, as well as Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Senator Jeff Flake (R-AZ), and Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT). Footnote 7

The meetings with Grassley and Hatch attracted public attention because both had previously met with each nominee since Sandra Day O’Connor. The attention Judge Garland’s meeting with Senator Grassley received was driven by the chairman’s position not to hold hearings. However, the scrutiny for Senator Hatch was generated by his support for Garland’s confirmation to the US Circuit Court of Appeals in 1997, as well as the suggestion that Garland would be a consensus nominee to replace Justice John Paul Stevens in 2010 (Ferraro Reference Ferraro2010). In 2016, President Obama used Hatch’s past statements to motivate the President Pro-Tempore to support Garland’s confirmation again.

From this intense position I watched an office balance concern for the senator’s preexisting relationship with the nominee and the risk that a political fight could politicize how lawmakers see the Supreme Court.

From this intense position I watched an office balance concern for the senator’s preexisting relationship with the nominee and the risk that a political fight could politicize how lawmakers see the Supreme Court. These concerns were balanced by recognizing the professional merit of Judge Garland and the importance of the Senate’s ability to be objective throughout the confirmation process were not mutually exclusive options. Another important observation was the openness of inter-office communication with the chairman and other colleagues when a senator indicated interest in meeting with the nominee.

Figure 1 illustrates Garland’s visits to Capitol Hill to promote a hearing. The five weeks between visiting with Senator Flake (R-AZ) in April and visiting with Senator Hatch (R-UT) in May suggests that office visits did not generate momentum to hold hearings. Moreover, Merrick Garland did not return to Capitol Hill after President Obama endorsed Hillary Clinton on June 9, 2016. This suggests the continuation of the presidential primaries distracted the Senate and stalled Garland’s nomination. Garland’s visits also provide us with a view of the potential loss of a Senate tradition. In the 114th Congress 45 senators (31-R, 14-D) had not experienced a Supreme Court confirmation. Without the encouragement of the Majority Leader and chairman, 26 of those junior senators (26-R, 0-D) did not meet with the nominee.

Figure 1 Senate Office Visits with the Supreme Court Nominee in the 114th Congress

During the vacancy a common task for staff was to monitor the actions of other senators that indicate support or opposition so that such information can be included in speeches or strategizing when to take action. Footnote 8 During a nomination a meeting with a nominee provides another measure of potential support by a colleague (Bowman 2016). For example, Senator Angus King (I-ME) stated “I want to see the reaction not only of the Senators but of the people of America as they have a chance to meet Judge Garland.” Footnote 9 In this case King was describing the value of a hearing, but his statement illustrates that the arguments and actions of bell-weather senators to predict what will happen next.

Declining Likelihood of Committee Hearings

Delaying a confirmation to the Supreme Court left party leaders concerned they might be labeled an ineffective majority. Therefore, the Senate considered other judicial nominees through regular order. During 2016, 40% of President Obama’s nominees to the US Circuit Court of Appeals and US District Court received a hearing. This attention to the full list of judicial nominees raises an interesting question of how senators have considered judicial nominees differently across time.

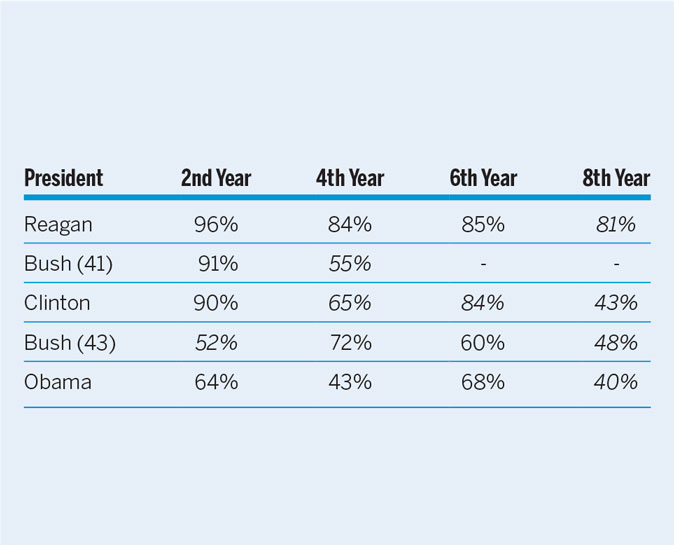

Drawing from the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Legislative Calendars from 1981 to 2016, we see the lowest percentages of nominees being granted a confirmation hearing occurred in 2012 and 2016. Table 1 also shows the lowest percentages of nominees receiving a hearing occurred in the eighth year of each administration. Another interesting point is that after the nuclear option was triggered, the number of nominees that received a hearing was 16% less than 1986 and 1998. The variation we see is not linear. Instead we see that there are different ways disagreements between senators over a nominee can exist within one’s own career based on changes in party control in the Senate and presidency.

Table 1 Frequency Pending Lower-Court Nominees Received a Hearing

Note: Percentages in italics represent years with divided government. These percentages include the number of nominees carried over from the first session of the Congress. Nominations remain active as long as the Senate does not send the president’s nominees back during a recess or at the end of a session (see Rule XXXI, paragraph 6).

If the timing of a nomination and dynamics of majority control do not signal a strong likelihood for confirmation, the Senate Judiciary Committee will often choose not to commit time to a difficult nomination. Given that all judicial nominees are referred to the Judiciary Committee, senators use examples from the more frequent lower court confirmations as analogies of the Senate’s contemporary style and approach to all nominations. Since 2000, less than half of the pending nominees have received a hearing in the eighth year of a president’s term. This trend suggests in 2016 the Senate applied, to the Supreme Court, the norm of majority control that has driven lower federal court confirmation for two decades.

The Senate’s procedural changes in response to gridlock have limited opportunities for senators to participate in debate and eroded the Senate’s deliberative style in favor of majority control. The rules of the Senate Judiciary Committee require a simple majority vote to report a nomination, however, the pressure to secure three-fifths support in the chamber led to a more inclusive process. The precedent to trigger the nuclear option in November 2013 overcame multiple filibusters on executive and lower court nominations. However, this also removed the incentive for bipartisanship on the floor, thereby changing the norms of the committee. In the first full year of majority-controlled confirmations there were 88 hearings to consider 128 pending nominees during President Obama’s sixth year in office. This opportunity to confirm more appointees led to the most hearings since 2003 when Chairman Hatch scheduled 87 committee hearings for lower court nominees.

Following the elimination of a super-majority threshold to end debate on a nominee we should expect substantial differences in how the confirmation process works under unified and divided government. During 2013 and 2014, breaking a filibuster with a majority vote removed a procedural barrier for Senate Democrats and the Democratic president leading to more hearings and more confirmations. However, the decline in hearings scheduled in the first Congress with divided government following the nuclear option suggests that this change is limited to periods of low party conflict. The likelihood of future inaction on some nominees was raised by Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) as he said, “Republicans here are naive to believe that Democrats wouldn’t avail themselves of the same precedent at some point in the future and hold up nominees being offered by Republican presidents.” Footnote 10 From this perspective we see that the actions of the Senate in 2016 serve to rebut the presumption of confirmation in a new political time.

CONCLUSION

The committee’s delay of the confirmation process challenged two norms of the modern Senate, senator-nominee meetings and the tradition of hearings for a nominee. The decision of the Senate Judiciary Committee not to hold a hearing until after the election influenced the frequency of senator-nominee meetings, particularly among the majority. The collaboration between party leaders to delay hearings was a position that could be understood by senators because of the Senate’s past behavior with lower court confirmations. Additionally, the later Senate primaries did not provide an electoral incentive to defect from the party line. Once senators faced pressure from the general electorate to support confirmation, the party nominees for president were already known.

Future research on nominations can be enriched by acknowledging the growing influence committee actions have in defining the Senate’s style. Clearly, presidents face constraints regarding who they nominate (Bond, Fleisher, and Krutz 2009; Moraski and Shipan Reference Moraski and Shipan1999), but we rarely discuss the strategies senators use to influence the confirmation process beyond the filibuster. My experience brought to bear that senators consider how each action they take will be interpreted, including what value can be gained by participating in the traditions of the institution. If party leaders are able to establish party unity in opposition of a president’s nominee, the benefit of participating in Senate traditions may decrease for rank-and-file senators in that party. However, these norms of the Senate continue to be valuable for members of the committee and senators that want to show support or fairness for the president’s nominee.

Polarization in the Senate has led to a decline in traditional norms (Mann and Ornstein Reference Mann and Ornstein2016). However, because we can observe more of the activity of individual senators we can identify new norms. The emerging norm of majority-control for all judicial nominations may create fewer opportunities for bipartisanship and deliberation, particularly when party conflict is high. This expectation applies to majority votes that can swiftly move a nominee through committee and the floor in unified government and the resistance of committees to automatically schedule a hearing. These actions force us to reconsider how the norms of senator-nominee meetings and hearings will be affected in the decades to come.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the generous time staffers in the US Senate, Senate Historians Office, the Senate Library, and researchers at the Congressional Research Service provided. I also want to thank Frances Lee and anonymous reviewers who offered many helpful suggestions in the development of this article.