On September 15, 2016, Donald Trump won a high-profile endorsement from the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), America’s largest and oldest police union (Kamisar Reference Kamisar2016). Following a vote of 45 state delegates, the FOP’s president, Chuck Canterbury, explained that although Trump had no prior experience as an elected official, the union would enthusiastically back his campaign because “He understands and supports our priorities and our members believe he will make America safe again.”

The FOP endorsement reverberated in a moment of racially charged polarization around policing. Responding to the Black Lives Matter movement and swelling anger in minority communities about police killings, many Democrats—including the party’s presidential nominee Hillary Clinton—embraced new rules opposed by police unions. The July 2016 Democratic Convention featured mothers of offspring killed by police officers, and Clinton did not seek the FOP’s endorsement. Meanwhile, the Republican Convention decried rising disorder in America and touted the need to back police. Trump regularly visited FOP lodges and declared that he was “on their side, 1,000 percent”—as he did on August 18, 2016, to officers at Lodge #27 in North Carolina. In early September, just before the FOP decision, Trump showily invited national police leaders to Trump Tower. Throughout the campaign, Trump boasted of this endorsement at rallies and lodge visits. He continued to tout FOP support after winning, as at a White House visit in March 2017 when he explained, “I will always have your back—100 percent, like you’ve always had mine, and you showed that on November 8th.”

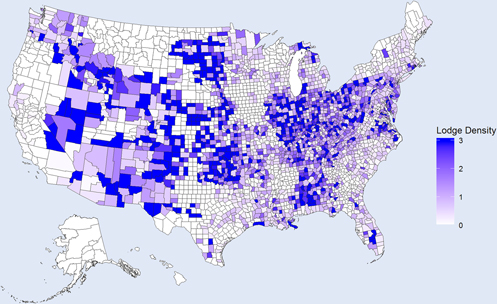

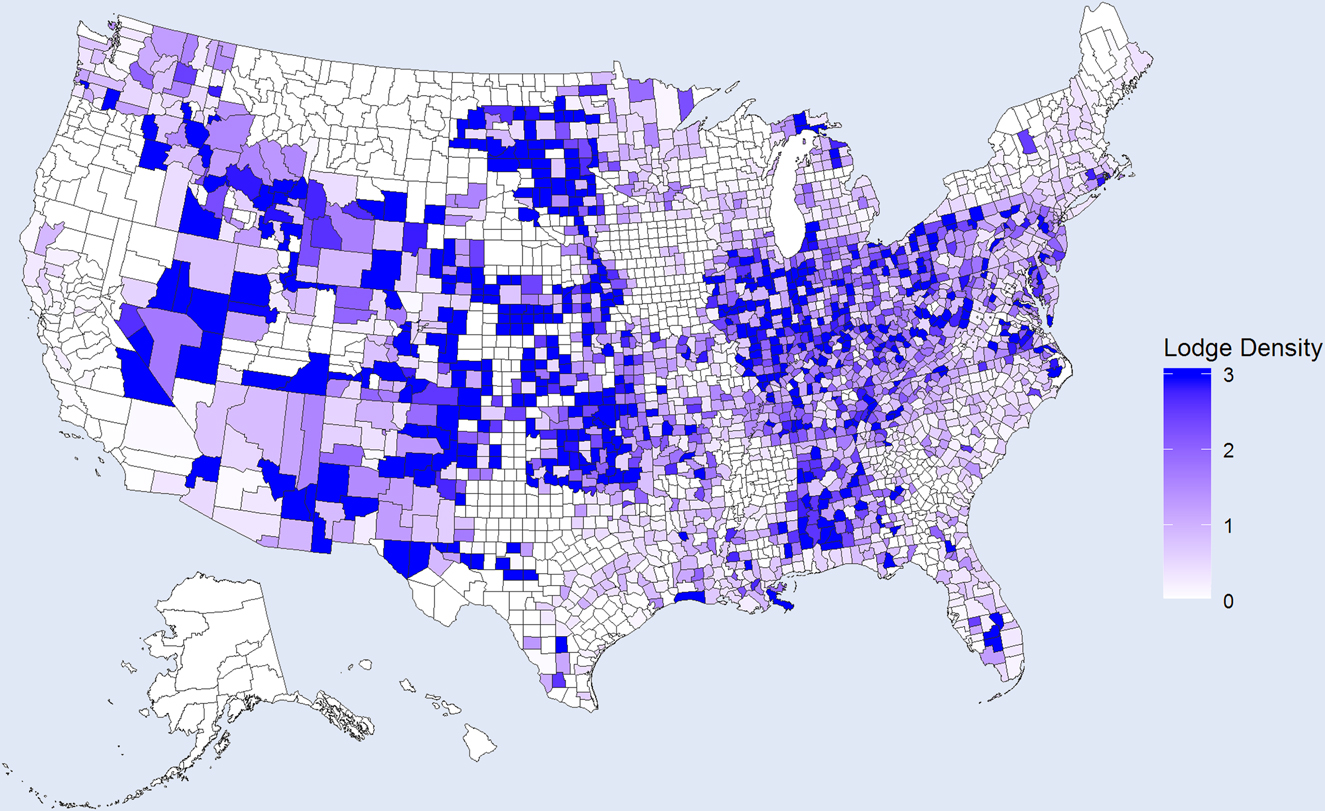

Support from the FOP is potentially valuable because it claims more than 300,000 dues-paying members and 2,000 active lodges—which are concentrated in swing states including North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania (figure 1) and broadly overlap with regions of 2016 GOP gains (figure 2). In 2012, the FOP refused to endorse either party’s presidential candidate because Romney opposed public-sector unions. The contrast between the FOP’s non-endorsement in 2012 and its enthusiastic endorsement of Trump in 2016 provides a unique opportunity to assess the effects of backing from an organized-membership federation. Scholars typically find it difficult to see what difference, if any, an endorsement makes because organizations repeatedly endorse the nominee of the party to which they are closest.

The contrast between the FOP’s non-endorsement in 2012 and its enthusiastic endorsement of Trump in 2016 provides a unique opportunity to assess the effects of backing from an organized-membership federation.

Figure 1 Fraternal Order of Police: Organizational Density. Lodges per 10,000 people, January 2016

Figure 2 Vote Shift from Romney to Trump (Percentage Points)

Most commentators have paid little heed to organizational backing for Trump. They attribute his victory to twists such as the investigation into Clinton’s emails and suggest that, as a former reality-TV star, Trump prevailed through media domination without an organized campaign. This article tests an alternative view—that is, that organized support of conservative networks, including the FOP, propelled Trump to victory. I first describe the FOP, a public-sector union and conservative, mass-membership fraternity. Then I outline several ways in which the FOP could affect electoral outcomes and present evidence that the police officers assiduously courted by Trump exhibited heightened political engagement in 2016. Finally, I present a difference-in-differences analysis suggesting that FOP lodge density contributed to a swing from Romney to Trump.

This research demonstrates the importance of organizations in shaping electoral politics. Moreover, it enriches our understanding of the 2016 presidential contest by showing that Trump did have a “ground game.” The FOP was an important part of that ground game in an election in which law and order was salient.

THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF THE FRATERNAL ORDER OF POLICE

The FOP formed in 1915 in Pittsburgh to improve the working conditions of police officers. At that time, the FOP strongly opposed police unions. The years following the notorious 1919 Boston police strike were not conducive to organizing. Nevertheless, the FOP spread by adopting patriotic, conservative, and anti-union stances. The anti-union position softened over time. By the 1960s, the FOP had embraced collective bargaining, partly in reaction to activism by other unions. In many states, FOP lodges now serve as collective-bargaining units, whereas in states that restrict collective bargaining, they are limited to fraternal and political activities (Gaines and Worrall Reference Gaines and Worrall2011, 326). However, the law-and-order stances persisted.

FOP political activism surged during the 1960s. In 1966, the FOP invited Alabama segregationist Governor George Wallace to speak at its national convention (Lesher Reference Lesher1994, 405). The FOP endorsed George Wallace in 1968 and Richard Nixon in 1972, and it regularly endorsed “law-and-order” candidates by 1976 (Arnesen and Lipari Reference Arnesen and Lipari2007, 483). In 1976, the FOP secured passage of legislation compensating the families of slain officers (Walsh Reference Walsh1977, 306). In 2004, President George W. Bush signed an FOP-backed act allowing law-enforcement officers to carry concealed firearms in all jurisdictions (Fraternal Order of Police 2013). State-level lobbying by the FOP has advanced the Police Bill of Rights, which protects officers accused of misconduct in a dozen states (Huq and McAdams Reference Huq and McAdams2016). More recently, the organization has backed legislation that makes the killing of a police officer a hate crime, leading to its introduction in several states and passage in Louisiana. In 2014, the FOP prevented the appointment of the proposed Department of Justice assistant attorney general for civil rights (Schreckinger Reference Schreckinger2015).

Although typically favoring Republicans in presidential races, the FOP did not endorse anyone in 2012, deeming Obama unfriendly to law enforcement and Romney critical of unions (Wheaton Reference Wheaton2016). The contrast between 2012 and 2016 is striking: in Ohio, press reports noted the FOP’s rebuke of Romney due to his support for Senate Bill 5, which would have prohibited public-sector collective bargaining (Torry Reference Torry2012). One interviewee at an Ohio lodge described the general sentiment: “Some of my members have flat-out said, ‘I will never again vote for someone who has an R next to their name because of what John Kasich did’” (Macgillis Reference Macgillis2012). The Trump campaign likely recognized the FOP’s unionism. His response to their questionnaire declined to take a stand on public-sector unionization, saying he would leave it to states.

Trump received votes from 39 of the 45 state delegations, well more than the two thirds required for a national endorsement. The remainder voted not to endorse anyone. The FOP’s Canterbury indicated that Clinton’s apathy explained her lack of support (Rentz Reference Rentz2016). FOP officials visited Trump Tower in August, telling reporters that they were “disappointed and shocked” by Clinton’s “snub” (Swan Reference Swan2016).

POLICING ISSUES AS A 2016 FLASHPOINT

Prior to the snub, the political cleavages around law enforcement had cast a shadow over the FOP and Clinton. The July Democratic Convention featured the mothers of people killed by police officers, a move that “shocked, angered, and saddened” the FOP, according to a viral press release (Swan Reference Swan2016). Posts on the FOP’s private forum also branded Barack Obama an “antipolice, anti-law and order president” (Swaine and Joseph Reference Swaine and Joseph2016). Throughout American history, police have gravitated to right-wing, law-and-order politicians and ethnocentric groups: “The police find few segments of the body politic who appreciate their contribution to society…if they do, they find this appreciation among conservatives, and particularly the extreme right” (Lipset Reference Lipset1972, 288). Trump fits this mold. In one primary debate, he said, “Police are the most mistreated people in this country.…We have to give power back to the police because crime is rampant” (Lee Reference Lee2016a). Trump’s win was thus a relief. The FOP leader in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania—traditionally a Democratic stronghold—cheered that “We, law enforcement, and the people needed this win” (Buffer Reference Buffer2016).

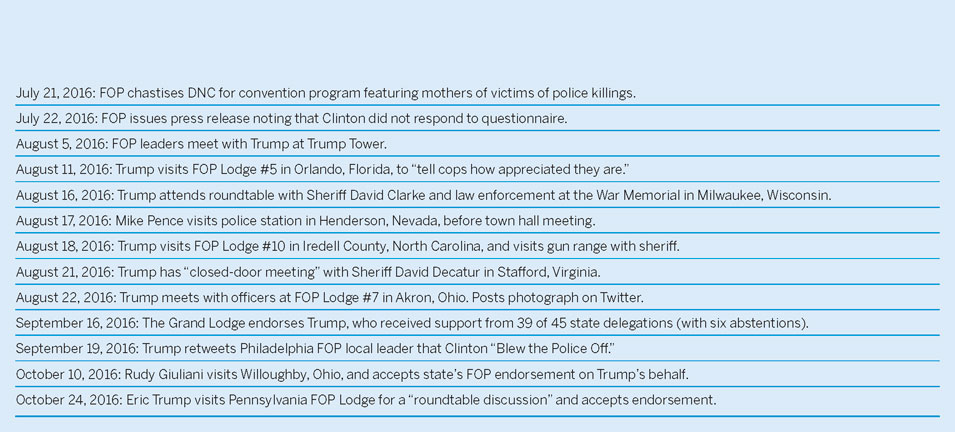

In clear contrast to Clinton, Trump actively courted the FOP. As illustrated in table 1, Trump reached out to police officers—and the FOP in particular—throughout the campaign, especially in the weeks preceding the endorsement vote. On August 11, he visited FOP Lodge #5 in Orlando, Florida, “just to tell cops how appreciated they are.” On August 16, in a speech in Wisconsin, Trump called Clinton “against the police” and billed himself as the “law-and-order” candidate. On August 18, he visited an FOP lodge in North Carolina, where he told members, “I’m on your side 1,000 percent Trump.” Before speaking at the lodge, he practiced shooting at the lodge’s gun range with the county sheriff, who told reporters, “I gotta say, this man can shoot” (Associated Press 2016; Swicegood Reference Swicegood2016). On August 21, Trump met with a sheriff in Virginia (Potomac Local 2016); the following day, he visited the FOP lodge in Akron, Ohio, sharing pictures of the meeting on Twitter (Livingston and Cottom Reference Livingston and Cottom2016).

The FOP’s executive director noted exceptional enthusiasm among members, a sentiment stemming from officers’ sense that they were “under siege.”

Table 1 Key Events

With the FOP endorsement came a promise to help the campaign. In the 2004 election, the Grand Lodge provided volunteers to the Bush campaign and launched a “get–out-the-vote campaign” of members and their families (Fraternal Order of Police 2004). The 2016 endorsement was equally wholehearted. The FOP’s executive director noted exceptional enthusiasm among members, a sentiment stemming from officers’ sense that they were “under siege.” As one interviewed officer stated, “With all the anti-police rhetoric that’s been going around, it was just refreshing. That’s what really drew me to Donald Trump in the first place” (Kaste Reference Kaste2016).

Several FOP leaders echoed the national endorsement and denounced Hillary Clinton. On September 18, Canterbury explained the endorsement on National Public Radio, saying, “[Trump] wants to work on the systemic causes of high crime, and Mrs. Clinton wants to work on police reform. And reform in a profession that doesn’t need to be reformed is not the answer to fight crime” (Martin Reference Martin2016). In Pittsburgh, the FOP head called Clinton’s choice to decline to seek the endorsement “terrifying.” He praised Trump as “giving the right answers…based on the constitution” (Schneider Reference Schneider2016). Philadelphia’s leader said Clinton “blew the police off” while Trump “cooperated” and “participated” (Giordano Reference Giordano2016).

The palpable enthusiasm for Trump by white law enforcement was controversial. A Clinton campaign canvasser in Cleveland reported that a police car drove down the street chanting “Trump, Trump, Trump” through its loudspeaker (Connors Reference Connors2016). San Antonio cops were disciplined for wearing pro-Trump hats while in uniform (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2016). A police union leader in Ohio was disciplined for attending a Trump rally in uniform (Gallek Reference Gallek2016). An Ohio sheriff published a picture of him and his team in uniform posing with Trump in a taxpayer-funded newsletter, a move criticized by the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (Glunt Reference Glunt2016). Trump also brought his support from police unions into the forefront: his campaign ran a television ad featuring Trump with uniformed Phoenix police officers, leading to a cease-and-desist letter from the city (Gardiner Reference Gardiner2016). Trump also frequently boasted of his FOP endorsement on the campaign trail (Lee Reference Lee2016b). Indeed, his support for the police may have been a defining characteristic: “Donald Trump…has been unwavering in his support of police officers” (McPhee Reference McPhee2016). This mutual affinity between Trump and white law enforcement reverberated throughout the media (see the appendix); by contrast, Clinton reportedly had a “prickly relationship with law enforcement” (Griffith Reference Griffith2016).

In contrast, leaders of black police organizations denounced the FOP’s Trump endorsement (Siemaszko Reference Siemaszko2016). The FOP has a racially fraught history, including support for George Wallace’s presidential campaign and staunch opposition to black mayors, including Cleveland’s Carl Stokes in the 1960s. Although the organization’s membership is 30% nonwhite, the seven-person national board remains all white. Many local lodges in places where the majority of officers are black are led by whites (Butler Reference Butler2017). In the 1960s and 1970s, black police organizations such as Blacks in Law Enforcement of America and Black Peace Officers Association formed to advocate on behalf of officers overlooked by majority police organizations (Love Reference Love2017). These groups, as well as local black police organizations, denounced Trump. The black Philadelphia Guardian Civic League, representing 2,500 officers, called Trump an “outrageous bigot” (Siemaszko Reference Siemaszko2016).

The Trump administration has repeatedly advanced FOP goals. Attorney General Jeff Sessions was hailed by the FOP as a “champion of law enforcement.” Canterbury gushed that “…I can say without reservation that I have never been able to testify with more optimism and enthusiasm” for a nominee. In his first months, Sessions curtailed consent-decree investigations (Hensch Reference Hensch2017) into police departments with systemic civil-rights violations, a long-time FOP goal (Charles Reference Charles2017). The move, rebuked by civil-rights groups, was welcomed by the FOP (Whack and Gurman Reference Whack and Gurman2017). A subsequent announcement “effectively [ended]” federal police reform efforts (Charles Reference Charles2017). In July, Sessions reversed an Obama-era restriction on civil-asset forfeitures (Delgadillo Reference Delgadillo2017). In August, he announced at the national FOP conference that Trump was rescinding the ban on transferring surplus military equipment to police (Lucas Reference Lucas2017).

HOW ORGANIZATIONS INFLUENCE ELECTIONS

The FOP is both a national public-sector union and a federation of fraternal associations. These features empower it to mobilize hundreds of thousands of members to shape politics (Leighley and Nagler Reference Leighley and Nagler2007). First, as a union, the FOP has experience utilizing endorsements, volunteering members for campaigns, giving contributions to candidates, and manipulating public opinion (DeLord, Burpo, and Shannon Reference DeLord, Burpo and Shannon2008). Second, as American history shows (Skocpol Reference Skocpol2003), long-standing fraternal associations have effected substantial political change through mass mobilization, as do contemporary membership organizations such as the National Rifle Association (NRA), an FOP ally (Grimaldi and Horwitz Reference Grimaldi and Horwitz2010).

Moreover, unions influence political participation beyond their membership through social networks (Ahlquist, Clayton, and Levi Reference Ahlquist, Clayton and Levi2014). As a federated organization, the FOP may be suited for collective action (Becher, Stegmueller, and Käppner, Reference Becher, Stegmueller and Käppner2018). Furthermore, police officers have high levels of in-group solidarity, often called “police culture,” which forms from the shared and stressful experience of police work (Loftus Reference Loftus2010). Thus, their networks may be especially potent. In 2016, many police officers, including FOP leadership, felt socially and physically threatened. With their consciousness as police “activated” by the political climate—and a clear choice between Clinton and Trump—police officers were ripe for mobilizing.

IMPACT OF THE FOP ENDORSEMENT

I tested the impact of the FOP endorsement in two ways. First, I examined individual-level political behavior of police officers in the 2016 election. Then, I estimated the effect of the endorsement on county-level election results using a difference-in-differences regression, modeling changes in Republican vote shares from 2012 to 2016 as a function of FOP presence, net of other factors.

Across various specifications—and holding constant other factors that explain Trump’s appeal—a significant and important association persists between the density of FOP lodges and the vote shift for Trump.

Political Activism by Law Enforcement

I tested how the 2016 election activated and mobilized police using the Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES), comparing changes in political behavior among police officers in 2016 and 2012 to changes among the voting-eligible public. Police were identified in the 2016 CCES using string matching of self-reported occupations; in the 2012 CCES, they were identified as those reporting to be working in “protective services” and for county or local government. This process identified 243 police officers in 2012 and 109 in 2016.

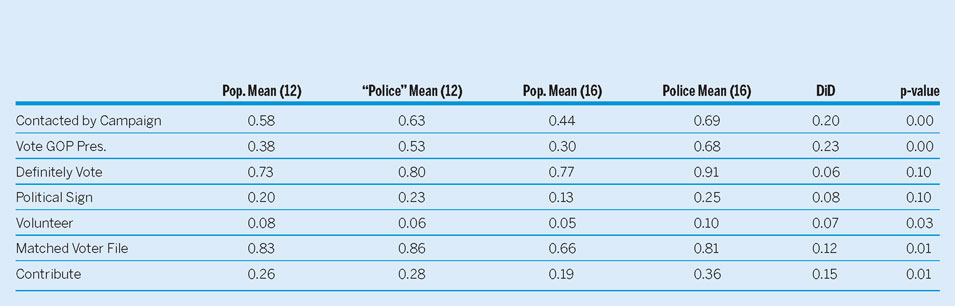

Police officers were highly engaged in 2016, as shown in table 2. Fully 69% of police officers reported that they were contacted by a campaign, compared to 44% of the general population. Of those reporting, 10% stated that they volunteered for a campaign or candidate and 36% contributed funds to a campaign; each behavior occurred at about twice the rate of the general population. Moreover, police officers became more politically engaged in 2016 than in 2012. Comparing the change in behavior between officers in 2016 and 2012 to the change among the public, officers were more likely (i.e., p<0.05) to report that they were contacted by a campaign, voted GOP for president, volunteered for a campaign, and contributed to a campaign.

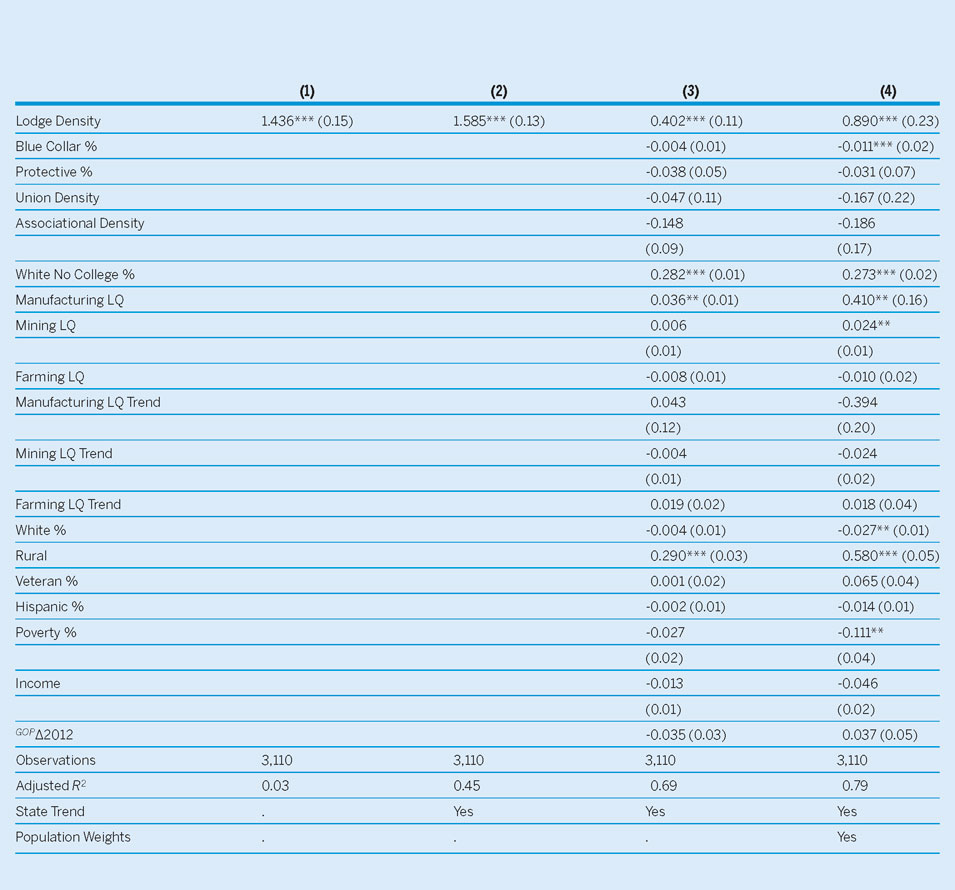

Table 2 FOP Strength and ∆ GOP Vote Share

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Difference in Differences in GOP Vote Share

Following a wealth of literature in political science that examines the number of local associations per person as a measure of organizational presence in a community (see the appendix), I used FOP per capita lodge density to assess FOP strength and its relationship to the vote shift to Trump. The results of four OLS regression models evaluating this relationship between FOP lodge density and vote shift toward Trump are shown in table 3. That is, the model compares the GOP vote share among counties of varying FOP presence across two presidential election cycles, after controlling for plausible confounders including racial and economic characteristics, percentage of county employment in protective services, and percentage of veterans. For additional details about data sources, control variables, and descriptive statistics, see the supplementary appendix.

Table 3 Political Behavior among Police Officers

Across various specifications—and holding constant other factors that explain Trump’s appeal—a significant and important association persists between the density of FOP lodges and the vote shift for Trump. In table 3, model 1 shows an association between lodge density and vote shift without covariates, model 2 adds state-trend dummies, and model 3 adds county-level covariates. The complete model 4, which includes population weights, indicates that a one-unit increase in lodge density is associated with a 0.9-percentage-point swing from Romney to Trump.

Assuming that this regression coefficient was causal and uniform across counties, I used it to calculate the counterfactual vote share that Trump would have received in each county without FOP support. The lodge density in each county multiplied by β provided the estimated change in vote share attributable to the FOP. Multiplying this quantity by the total number of votes in the county and aggregating this number of county-level votes attributable to the FOP to the state level provided a “back-of-the-envelope” indication of the counterfactual electoral map. In Michigan, the model implied a GOP two-party vote swing of 0.3 percentage points, or about 15,400 votes, attributable to the FOP—a quantity that exceeds the number of votes by which Trump won the state. In Pennsylvania, birthplace of the FOP, the associated swing was 0.7 percentage points, or about 31,800 votes. The supplementary appendix further discusses the procedures used to estimate and interpret the effect size.

LAW AND ORGANIZATIONS IN 2016

Trump’s win in November 2016 was so surprising to most scholars and pundits that their retrospective accounts stressed unique events and media celebrity. Organizational factors received hardly any attention. However, this article uses evidence from campaign events, data on police political behavior, and vote shares to make the case that widespread organizational networks may have been critical. Trump 2016 improved on Romney 2012 in places of FOP strength.

Available data and the FOP’s non-endorsement in 2012 allowed me to probe this particular organization. However, other networks likely weighed in for Trump, including the NRA, Americans for Prosperity, and evangelical churches. For now, these results underscore the value of this line of research. For presidential contests especially, widely connected organizational networks can be built (e.g., in the 2008 Obama campaign) or borrowed (e.g., in the 2016 Trump campaign). However, they are unlikely to be irrelevant. For Trump in 2016, blue endorsements mattered precisely because police are so widely organized across communities. When hundreds of thousands of men and women in blue proclaimed Trump their candidate, many other Americans got the message.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518001841