Centralisation & farming practice, South-west Germany

Introduction

Late Iron Age oppida have long been considered the ‘earliest towns north of the Alps’ (Collis Reference Collis1984a), but new findings have challenged this traditional view of early centralisation and urbanisation in central Europe, revealing that the first urban centres in the region date back to the end of the 7th century bc (Krausse Reference Krausse2008; Reference Krausse2010; Brun & Chaume Reference Brun and Chaume2013). While the hallmarks of urbanism remain debated and are often difficult to identify archaeologically (Fernández-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Wendling and Winger2014), new investigations suggest that many Early Iron Age Fürstensitze or ‘chiefly seats’ of south-west Germany had higher populations than previously thought and occupied central positions of economic as well as political power, impacting on their wider hinterland (Kurz Reference Kurz2010; Fernández-Götz & Krausse Reference Fernández-Götz and Krausse2013). While past research has tended to focus on trade links between these fortified settlements and the Mediterranean, such central places are unlikely to have emerged without the necessary social, political, and economic infrastructures to support them (Collis Reference Collis1984b). This study focuses on reconstructing how the agricultural basis of society was able to support these new centres of population and production. Such investigations are crucial to understanding the wider context in which such centralisation took place and also in identifying the causes and consequences of this process.

Diversification and increase in (surplus) production are both archaeologically visible strategies that early farmers employed to manage risk and thus ensure sufficient food supply (Marston Reference Marston2011). Crop diversification moderates the overall variance in production should a particular crop fail, and there is archaeobotanical evidence for expanding crop spectra in central Europe – especially from the Late Bronze Age – when broomcorn and foxtail millet, spelt wheat, and perhaps oats and rye supplemented the ‘Neolithic assemblage’ of naked wheat, einkorn, emmer, and barley (Jacomet et al. Reference Jacomet, Rachoud-Schneider and Zoller1998; Rösch Reference Rösch1998; Kreuz & Schäfer Reference Kreuz and Schäfer2008).

Determining whether or not increased production was achieved, and how – whether through intensification (increasing labour and resource inputs per unit area of cultivated land) and/or extensification (expansion of cultivated land that tends to result in lower inputs per unit area) – is more difficult (eg, van der Veen & O’Connor Reference van der Veen and O’Connor1998; van der Veen Reference van der Veen2005). Intensive cultivation requires high labour and resource inputs per unit area of land to ensure high area yields, such that productive capacity is limited by available labour. This mode of production is particularly suited to management at a household level – integration of small-scale crop cultivation and livestock herding appears to have provided a resilient Neolithic subsistence base enabling risk to be managed by small family groups (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2015a).

In contrast, extensive cultivation involves significant expansion of arable land, such that reduction of inputs and yields per unit area are offset by a larger absolute scale of production (Halstead Reference Halstead1995). Extensification can occur through implementation of labour-saving techniques such as ploughing, combined with use of specialised plough animals capable of preparing a much larger area for sowing than can be achieved manually by a farming family. Such radical expansion in arable scale requires an additional supply of landless labour at harvest time, a system that is consistent with elite intervention in land ownership and production. Moreover, plough oxen are costly to support and their use is often managed through exchange agreements between owners and users (Halstead Reference Halstead2014, 42 & 303) – an opportunity for an elite to control and restrict the means of production. However, evidence for ploughing per se is not proof of very large-scale agriculture. Animal traction can also serve to increase inputs per unit area by facilitating transport of manure, and the degree of expansion in scale in comparison with manual systems could in fact be modest if, for example, animals were not specialized plough oxen and/or additional labour needed to harvest large areas was not available (Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2011).

An example of direct elite involvement in production comes from Linear B tablets from the Late Bronze Age palace of Knossos, on Crete (eg, Chadwick et al. Reference Chadwick, Godart, Killen, Olivier, Sacconi and Sakellarakis1987; Halstead Reference Halstead1999; Reference Halstead2001). These record grain contributions and list pairs of working oxen, and imply palatial involvement in the production of wheat, probably emmer (Halstead Reference Halstead1999; Reference Halstead2001). This cereal was likely chosen for its stress-tolerance and grown on a larger scale, with fewer inputs per unit area than the broader range of cereals and pulses reflected in the archaeobotanical record (Halstead Reference Halstead2001). Without such textual evidence in central Europe, the extent to which agricultural production in the Early Iron Age was controlled by an elite and how this related to wider centralisation processes remains speculative (Frankenstein & Rowlands Reference Frankenstein and Rowlands1978; Reynolds Reference Reynolds1995; Earle Reference Earle2002). Emerging archaeobotanical evidence is consistent with a focus on certain cereal crops including hulled barley at Iron Age fortified hilltop centres (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010), but this raises the question of whether these selected crops were produced on a larger scale – under lower input conditions than other crops – as a direct elite intervention model would suggest.

In this study, we use two novel archaeobotanical approaches – functional weed ecology and crop stable isotope analysis – to determine directly how the intensity of agricultural practice changed from the Neolithic to the Early Iron Age in south-west Germany, and also to compare the intensity of agricultural practice at Early Iron Age rural and fortified hilltop sites. We use faunal isotope analysis to provide complementary evidence of landscape use and variation in animal diet and herding practices. Reconstructing the scale of agricultural production and the level at which decisions were made is integral to understanding the basis of the Early Iron Age subsistence and political economy.

The agricultural landscape in south-west Germany from the Neolithic to the Early Iron Age

Palynological studies indicate that early farming involved small-scale forest clearance (Kalis et al. Reference Kalis, Merkt and Wunderlich2003). Low levels of woodland perennials in weed assemblages suggest that cultivation was carried out on long-lived plots throughout the Neolithic in south-west Germany (c. 5500–2500 bc; Maier Reference Maier1999; Brombacher & Jacomet Reference Brombacher and Jacomet1997), though there is ongoing discussion about the interpretation of regional pollen data as evidence for shifting cultivation (Rösch Reference Rösch1990; Jacomet Reference Jacomet2008; Rösch et al. Reference Rösch, Kleinmann, Lechterbeck and Wick2014; Jacomet et al. Reference Jacomet, Antolin, Akeret, Bogaard, Baum, Brombacher, Bleicher, Ebersbach, Heitz-Weniger, Hüster-Plogmann, Gross, Kühn, Rentzel, Schibler, Steiner and Wick2016). These early agricultural plots were characterised by highly productive and disturbed soils, akin to modern intensively and manually cultivated ‘gardens’ (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004; Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011), with adequate area yields achieved through high labour inputs (ie weeding, hoeing, manuring). Crop nitrogen isotope (δ15N) values provide direct evidence that manuring formed part of this intensive farming regime at Early Neolithic Vaihingen an der Enz in the Neckar river basin, as well as at Late Neolithic Hornstaad-Hörnle IA and Sipplingen-Osthafen in the Alpine foreland (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Schäfer, Arbogast and Heaton2013b; Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a). Within these intensive regimes, both the functional weed ecology and crop δ15N values indicate considerable variability in soil fertility, disturbance, and manuring intensity, within and between settlements (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004; Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011; Reference Bogaard, Fraser, Heaton, Wallace, Vaiglova, Charles, Jones, Evershed, Styring, Andersen, Arbogast, Bartosiewicz, Gardeisen, Kanstrup, Maier, Marinova, Ninov, Schäfer and Stephan2013; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Schäfer, Arbogast and Heaton2013b; Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a). The variability in crop δ15N values between households at Hornstaad-Hörnle IA supports other archaeological evidence (eg, similar sets of tools per house; Dieckmann et al. Reference Dieckmann, Maier and Vogt2001) for a domestic mode of production, while the association of distinctive weed groupings with neighbourhoods suggests strategic cooperation between related households, or ‘clans’, at Vaihingen an der Enz (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Krause and Strien2011).

Hoe-like digging implements were found in almost every house at Late Neolithic Hornstaad-Hörnle IA (3918–3902 bc; Dieckmann et al. Reference Dieckmann, Maier and Vogt2001), but there is no evidence for yokes or ard-ploughs at this time. The earliest wheels appear in the waterlogged deposits of the Alpine foreland at the end of the 4th millennium bc, and the proliferation of roadways preserved in wetlands around the Alps, including at Sipplingen, attest to the growing importance of cattle traction (eg, Schlichtherle Reference Schlichtherle2006). Evidence for use of cattle for traction (which could be associated with transport or ard-ploughing) is demonstrated by ‘traction pathologies’ at Arbon Bleiche on the southern shore of Lake Constance (3384–3370 bc; Deschler-Erb et al. Reference Deschler-Erb, Leuzinger and Marti-Grädel2006) and by cattle mortality profiles at sites at the northern end of Lake Zurich (c. 3300–2700bc; Hüster-Plogmann & Schibler Reference Hüster-Plogmann and Schibler1997). Settlement occupation at Sipplingen spans this period, but despite weed and pollen data indicating that the landscape became more open (Jacomet Reference Jacomet1990; Lechterbeck et al. Reference Lechterbeck, Edinborough, Kerig, Fyfe, Roberts and Shennan2014), and initial occurrences of species regarded as arable weeds today (Jacomet Reference Jacomet1990; Billamboz et al. Reference Billamboz, Baum, Kaiser, Maier, Matuschik, Müller, Stephan, Steppan, Schlichtherle and Vogt2013), there is no corresponding decrease in crop δ15N values that would indicate a reduction in the intensity of manuring (Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a). Rather, manuring levels seemed to have been maintained, perhaps due to the growing availability of manure from larger numbers of cattle. From the crop isotope results it has thus been suggested that, although the adoption of draught animals led to a tendency towards more extensive farming regimes by expanding the area under cultivation, there was no radical shift to a fundamentally different farming system with lower manure inputs per unit area (cf. Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2011). Weed ecological analysis of one suitable sample from Corded Ware levels at Mythenschloss on Lake Zurich (c. 2700–2400 bc) also suggests continuity in intensive cultivation (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004, 168).

A continuation of the 4th millennium trend towards more widespread use of cattle traction during the Bronze Age has been inferred from finds of ard ploughs, plough marks, wheeled carts, and yokes in various areas of Europe, as well as ‘traction pathologies’ and cattle mortality profiles (Hüster-Plogmann & Schibler Reference Hüster-Plogmann and Schibler1997). Furthermore, geoarchaeological and palynological studies across central Europe suggest that the landscape became increasingly open, with marked deforestation (Kalis et al. Reference Kalis, Merkt and Wunderlich2003), fields with short fallow phases, and a clear increase in open pastures (Lechterbeck et al. Reference Lechterbeck, Edinborough, Kerig, Fyfe, Roberts and Shennan2014).

Lasting social differentiation emerges at various points during the central European Bronze Age, most clearly evidenced by the Late Bronze Age barrow burials and the development of regional settlement hierarchies (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen1998, 111–15; Harding Reference Harding2000, 71–2). The presence of deep pits and four-post structures in many Late Bronze Age settlements (Harding Reference Harding2000, 66–7 & 132) has been interpreted as centralised storage in addition to storing of crops at a household level. Arable weed evidence from a range of sites in central Europe suggests a shift towards more extensive agriculture and eroded soils, together with the cultivation of crop types thought to be adapted to less productive conditions (ie hulled barley and spelt wheat; Kroll Reference Kroll1997; Rösch Reference Rösch1998; Jacomet & Brombacher Reference Jacomet and Brombacher2009). Only three samples dating to the Bronze Age have been subject to functional weed ecological analysis (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004, 168). These span the range of agricultural intensity, which again suggests that even when ploughing was widely practiced, there was variation in soil fertility and disturbance (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2011).

The Early Iron Age (800–450 bc) in central Europe saw the proliferation of fortified hilltop settlements, often associated with rich burial mounds, in southern Germany, eastern France, Switzerland, Bohemia, and Upper Austria (Kimmig Reference Kimmig1969). Not only do these burials provide evidence for the rise of an elite class, the presence of imported Greek and Etruscan luxury items in these burial mounds and associated settlements points to elite control over a trade network extending as far as the Mediterranean (Collis Reference Collis1984b, 82–94). The location of the richest sites on rivers with access to the main fluvial trade route from Marseilles and evidence for specialist metal, glass, and pottery production point to their role as centres of production and trade (Collis Reference Collis1984b, 79–82).

However, interpretations largely based upon burial evidence must be treated with caution, and while the fortified hilltop settlements are the most visible forms of Early Iron Age occupation, it is likely that they were in fact an ‘eccentric extreme’ (Collis Reference Collis1984b, 101) rather than the norm. A recent research project, entitled Frühe Zentralisierungs- und Urbanisierungs-prozesse. Zur Genese und Entwicklung frühkeltischer Fürstensitze und ihres territorialen Umlandes (‘Early Centralisation and Urbanisation Processes. On the Origin and Development of Early Celtic Princely Sites and their Environs’) has sought to broaden understanding of Early Iron Age society in south-west Germany beyond that of the rich burial mounds and fortified settlements. Findings from past studies were integrated with more recent excavations and a host of archaeozoological, archaeobotanical, palynological, and spatial investigations to provide a better insight into the agricultural basis of these past societies (Krausse Reference Krausse2008; Reference Krausse2010).

Pollen evidence indicates progressive deforestation since the Bronze Age, resulting in an Early Iron Age landscape that was largely open, with very little dense forest (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010). In regions with more fertile soils, high proportions of hare bones suggest that the landscape was dominated by agricultural land, with only small patches of woodland (Schatz & Stephan Reference Schatz and Stephan2008). High proportions of sheep and goat bones at sites in these areas suggest that smaller ruminants were preferentially pastured here. In contrast, regions with less fertile soils had higher proportions of red deer and wild boar bones, indicating more densely forested land (Schatz & Stephan Reference Schatz and Stephan2008). At the Heuneburg, situated in a relatively infertile region, the high proportion of cattle and pig bones suggests that there was a stronger emphasis on a meat and livestock-based economy (Schatz & Stephan Reference Schatz and Stephan2008). It has therefore been suggested that there was spatial differentiation between regions, those with more fertile soils being used primarily for arable farming, and those with less fertile soils and steep slopes for grazing animals (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010).

Archaeobotanical investigations found that certain crop species were dominant at the fortified hilltop sites, in contrast to a more even representation of a wider spectrum of crop species at rural settlements. In the fortified hilltop settlements, hulled six-row barley and (to a lesser extent) spelt wheat predominate, and this is attributed to the import of surplus production of these crops from their rural hinterland, probably to support the more concentrated population (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010). The presence, albeit in lower abundances, of other crop species at the fortified hilltop sites (emmer, einkorn, and pulses) is interpreted to suggest that small-scale subsistence cultivation was still taking place locally, but that the import of large quantities of barley and spelt wheat supplemented this production. These findings resemble those of archaeobotanical studies in England, where pits used for storing cereal grain, concentrated in hillforts, have been most recently interpreted as evidence for large-scale cereal production and consumption (van der Veen & Jones Reference van der Veen and Jones2006). Moreover, a shift from emmer to spelt wheat in some regions of England in the Late Iron Age is attributed to an expansion in cereal production and cultivation of more marginal soils (van der Veen Reference van der Veen1992; van der Veen & O’Connor Reference van der Veen and O’Connor1998). Ecological analysis of Iron Age weed flora in north-east England demonstrates variation in the intensity of land management among sites and crop species (van der Veen Reference van der Veen1992).

In contrast to the densely populated Mediterranean towns of the time, new excavations at the Heuneburg have revealed that its outer settlement comprised sizeable farmsteads with evidence for small-scale crop and animal husbandry within their enclosures (Fernández-Götz & Krausse Reference Fernández-Götz and Krausse2013). This indicates that the disconnect between consumer and agricultural producers in these Early Iron Age centres was not as great as might first be assumed (cf. Gallagher & McIntosh Reference Gallagher and McIntosh2015). Settlements contained various storage structures (four post structures interpreted as granaries or barns and pits) and sometimes systems of posts or ditches interpreted as fences enclosing gardens and/or penning areas (de Hingh Reference de Hingh2000; Biel Reference Biel2015, 50).

This recent work provides valuable insights into the diversification of crop and animal husbandry practices based on the suitability of soils for agriculture and the suspected import of crops from rural to fortified hilltop settlements. While it is plausible that agricultural production increased in order to provide the surplus to support these fortified hilltop sites, the existing evidence cannot determine whether this was achieved through more intensive (increased labour investment per unit of land) or more extensive cultivation methods. We therefore turn to the integration of two novel methods – functional weed ecology and crop isotope analysis – to identify the intensity of agriculture practised in the Early Iron Age, and determine whether this differed between rural and fortified hilltop settlements. Faunal isotope analysis provides complementary evidence of animal diet and herding practices and allows us to estimate an isotopic baseline for unmanaged plants.

Reconstructing past farming practice through the ‘weed + isotope’ approach

Since the biogeographical distribution of weed species has changed through time, direct comparison of species composition between modern and ancient weed flora is difficult. In this study, we distinguish between farming regimes based on the functional attributes of the weeds – ie those attributes that allow them to flourish under particular conditions. This not only allows translation of present-day cultivation practices to the past, but also provides a means of distinguishing the effects of different regimes, thus allowing identification of novel combinations of farming practices that no longer exist today (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Bogaard, Charles and Hodgson2000; Reference Jones, Charles, Bogaard and Hodgson2010). Studies of weed flora from modern small-scale/high-intensity cereal plots in Asturias, Spain and large-scale/low-intensity (extensive) fields in Haute Provence, France allowed a model of cultivation intensity to be developed, based on five functional attributes that reflect the response of weed species to soil productivity and/or mechanical disturbance (tillage and weeding; Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016, table 3; Appx S.1). Discriminant analysis is used to extract a linear equation combining these functional attributes with the aim of maximising the separation between intensive and extensive farming regimes (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016). Cultivated plots containing weeds with functional attributes associated with high soil productivity and high disturbance group to the ‘high-intensity’ end of the spectrum, since these indicate high levels of fertilisation (ie manure), tillage, and weeding, which require high labour inputs. Cultivated plots containing weeds with functional attributes associated with low soil productivity and low disturbance group to the ‘low-intensity’ end of the spectrum.

Crop nitrogen isotope (δ15N) values largely reflect the δ15N value of the soil in which crops are grown, which itself reflects the δ15N value of nitrogen (N) inputs and subsequent effects of N cycling processes (eg, Högberg Reference Högberg1997). Potential causes of high plant δ15N values are: i) recent forest clearance by burning (eg, Szpak Reference Szpak2014); ii) seasonal waterlogging of soils (Finlay & Kendall Reference Finlay and Kendall2008); and iii) high levels of organic N relative to plant demand (Aguilera et al. Reference Aguilera, Araus, Voltas, Rodrìguez-Ariza, Molina, Rovira, Buxó and Ferrio2008). All of these processes lead to preferential loss of 14N, leaving 15N-enriched nitrogen in the soil for plants to take up. In agricultural systems, a major influence on crop δ15N values is the addition of 15N-enriched manure. Studies of modern crops have found that manuring can increase cereal δ15N values by as much as 10‰ across a range of locations and soils, according to the intensity – amount and frequency – of manuring (eg, Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Heaton, Charles, Jones, Christensen, Halstead, Merbach, Poulton, Sparkes and Styring2011; Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016). Manuring intensity (and this could include middening and composting) is therefore likely to override the effects of other variables, such as soil type and soil nitrogen content, on crop δ15N values in farming systems (cf. influence of land use in Peukert et al. Reference Peukert, Bol, Roberts, Macleod, Murray, Dixon and Brazier2012; Thornton et al. Reference Thornton, Martin, Procee, Miller, Coull, Yao, Chapman, Hudson and Midwood2015).

There are clear advantages to combining functional weed ecology and crop δ15N values in order to reconstruct agricultural practice and growing conditions. Functional weed ecology can reveal the permanence of arable land, and also provide evidence for the level of soil disturbance (due to tillage and weeding; Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004). While weed ecology also provides a general index of soil productivity, crop δ15N values provide an opportunity to test whether greater nitrogen availability (associated with soil productivity) does indeed result in higher crop δ15N values. Weeds are influenced by the flora in the wider environment, integrating the effects of more general landscape change rather than merely the conditions in a particular plot (Rösch Reference Rösch1998). Crop δ15N values, in contrast, offer a direct determination of the nitrogen isotope composition of the soil in which they were grown, which if resulting from manuring, permits comparison of manuring intensity between different crop species regardless of whether they were mixed after harvest. These two approaches are therefore subject to different sources of error and ambiguity, so interpretations that combine evidence from both are more robust and informative than those based on one form of evidence alone (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2015b).

Materials and methods

Selecting sites

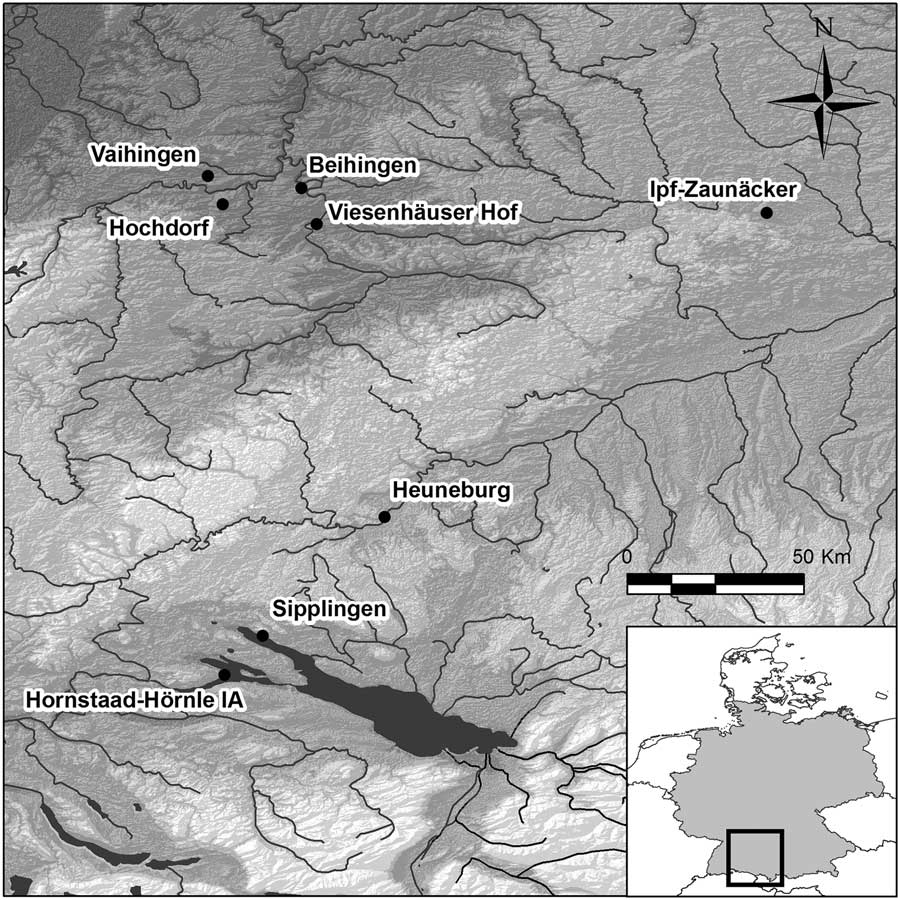

In this study we determine the functional weed ecological attributes and crop δ13C and δ15N values for crop assemblages from five Early Iron Age sites in south-west Germany (Fig. 1 & Table 1), in order to identify how the intensity of agriculture changed with centralisation. These sites consist of those studied in the recent Frühe Zentralisierungs- und Urbanisierungsprozesse project, whose archaeobotanical assemblages contained a minimum of five discrete contexts with a minimum of five well-preserved grains/seeds in each. The Heuneburg (more precisely samples from the Vorburg, or lower town area) was the only fortified hilltop settlement with enough crop remains for isotope analysis. Since change in agricultural intensity can only be detected using a diachronic approach, we also include crop isotope data from four Neolithic sites in the same region (Fig. 1 & Table 1), plus functional weed ecological data for these and other previously collated samples from Neolithic sites in south-west Germany (Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004; Reference Bogaard2011); there were insufficient archaeobotanical remains dating to the Bronze Age. The Neolithic crop isotope data come from previously published studies by this research group (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Fraser, Heaton, Wallace, Vaiglova, Charles, Jones, Evershed, Styring, Andersen, Arbogast, Bartosiewicz, Gardeisen, Kanstrup, Maier, Marinova, Ninov, Schäfer and Stephan2013; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Schäfer, Arbogast and Heaton2013b; Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a) and new isotope data from Stuttgart-Mühlhausen Viesenhäuser Hof (see Stika Reference Stika2009 and Rösch Reference Rösch2014 for more information on the archaeobotany of this site).

Fig. 1 Map of south-west Germany showing location of archaeological sites included in this study. See Table 1 for their unabbreviated names

Table 1 Details of the archaeological sites in this study

Selecting and preparing crop samples for isotope analysis

Each crop δ13C and δ15N value represents a homogenised batch of between four and ten carbonised cereal grains or pulse seeds of the same taxon from the same ‘deposit’. Multiple grains per sample are combined in order to average out some of the inherent natural variation in cereal grain δ13C and δ15N within a single field (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Charles, Styring, Wallace, Jones, Ditchfield and Heaton2013a; Nitsch et al. Reference Nitsch, Charles and Bogaard2015). By averaging out some of this variation at a sampling level, it is easier to detect differences in δ15N due to differences in growing conditions, potentially reflecting manuring intensity. Cereal grains and pulses were examined at ×7–45 magnification for visible surface contaminants, such as adhering sediment or plant roots; these were removed by gentle scraping. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to look for the presence of carbonate, nitrate, and/or humic contamination (cf. Vaiglova et al. Reference Vaiglova, Snoeck, Nitsch, Bogaard and Lee-Thorp2014) (see Appx S.2–S.4 for more details). On the basis of these results, it was decided not to pretreat any of the samples. Samples, after being homogenised by crushing, were weighed into tin capsules for stable isotope analysis.

Selecting and preparing faunal bone samples for isotope analysis

The δ13C and δ15N values of wild and domestic faunal bone collagen from the same archaeological sites as the carbonised crop remains were also determined. For the most part these data are new, but the faunal isotope values from Vaihingen (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Schäfer, Arbogast and Heaton2013b), Hornstaad-Hörnle IA (Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a), Sipplingen (Steppan & Stephan Reference Steppan and Stephan2012), and Neolithic Viesenhäuser Hof (Knipper Reference Knipperin press) have been determined in previous studies. The individual isotope values for fauna from Sipplingen are not presented. Between 0.5 g and 1 g of bone was cleaned of any visible dirt or carbonate crusts using an aluminium oxide air abrasive. Collagen was isolated using a modified ‘gelatinisation method’ based on the methods of Longin (Reference Longin1971). Bone collagen samples of approximately 1 mg were weighed into tin capsules for stable isotope analysis.

Stable isotope analysis

The δ13C and δ15N values of bone collagen and carbonised crop remains were determined on a SerCon EA-GSL mass spectrometer. The δ13C and δ15N values of carbonised crop remains were determined in separate runs due to the low %N in the samples. An internal alanine standard was used to calculate raw isotope ratios. For δ13C determinations of carbonised crop remains, two-point normalisation to the VPDB scale was carried out using four replicates each of IAEA-C6 and IAEA-C7, while for δ15N determinations the standards were caffeine and IAEA-N2. For δ13C and δ15N determinations of bone collagen, two-point normalisation was carried out using four replicates each of caffeine and seal bone collagen. Reported measurement uncertainties are the calculated combined uncertainty of the raw measurement and reference standards, after Kragten (Reference Kragten1994). The average measurement uncertainties for δ13C and δ15N of carbonised crop remains were 0.23‰ and 0.49‰, respectively. The average measurement uncertainties for δ13C and δ15N of bone collagen were 0.18‰ and 0.23‰, respectively. The δ13C and δ15N values of carbonised crop remains were corrected for the effect of charring by subtracting 0.11‰ and 0.31‰, respectively, from the determined δ13C and δ15N values (Nitsch et al. Reference Nitsch, Charles and Bogaard2015).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical programming language R. (3.0.2). To compare two groups with normally distributed data, a Welch’s two-sample t test was used; to compare two groups with non-normally distributed data, a Mann-Whitney U test was used; and to compare multiple groups with normally distributed data, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. Levene’s test was used to assess whether the variances of two groups are equal. Linear mixed-effects models were used to look for the effect of fixed variables on isotope values, whilst accounting for a random effect of site. For the results of the statistical analyses mentioned in the text, see Table 2.

Table 2 Details of the results of statistical tests carried out on the crop and faunal isotope data. P values <0.05 are shown in bold

* Results of a Mann-Whitney U test carried out because δ15N values of domestic herbivores are non-normally distributed

** Excluding an outlier with δ15N of 8.8‰

Estimating a δ15N baseline for unmanaged plants from herbivore bone collagen δ15N values

Since plant δ15N values can vary spatially due to myriad environmental factors (summarised in Peukert et al. Reference Peukert, Bol, Roberts, Macleod, Murray, Dixon and Brazier2012), it is necessary to estimate the δ15N of unmanaged plants at each archaeological site, in order to distinguish the effect of manuring from natural differences in δ15N. The approach of recent studies (eg, Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Fraser, Heaton, Wallace, Vaiglova, Charles, Jones, Evershed, Styring, Andersen, Arbogast, Bartosiewicz, Gardeisen, Kanstrup, Maier, Marinova, Ninov, Schäfer and Stephan2013; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Schäfer, Arbogast and Heaton2013b; Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a–Reference Styring, Ater, Hmimsa, Fraser, Miller, Neef, Pearson and Bogaardb) has been to estimate the δ15N of plants consumed by [wild] herbivores found at the same archaeological site/phase, by subtracting the mean offset between herbivore bone collagen and diet (c. 4‰; eg, Steele & Daniel Reference Steele and Daniel1978) from the δ15N values of preserved herbivore bone collagen. In this study, the range of estimated unmanaged (ie, unmanured) cereal grain δ15N values is calculated from the wild herbivore diet δ15N value ± 1 standard deviation (green shading in Fig. 3).

For the Neolithic, the mean δ15N of wild herbivore bone collagen (and therefore the unmanaged cereal grain δ15N baseline) is 1.6‰ lower at the lakeshore site of Hornstaad-Hörnle IA than at Vaihingen, situated on loess soils in the Neckar basin (Table 2: 2; Fig. 3). The range of unmanaged plant baseline δ15N values calculated from the mean wild herbivore bone collagen δ15N value from Vaihingen is also used for Viesenhäuser Hof, since the single wild herbivore δ15N value determined from the Neolithic levels at Viesenhäuser Hof (possible aurochs; Knipper Reference Knipperin press) does not differ greatly from the mean δ15N value of wild herbivores at Vaihingen. There is no significant difference in the δ15N values of wild herbivores between Early Iron Age sites (Table 2: 15), so their δ15N values are combined to estimate the range of δ15N values of wild herbivore diet at all Early Iron Age sites (Fig. 3).

Selecting samples for functional weed ecological analysis

Samples selected for weed ecological analysis contained a minimum of ten potential weed seeds (ie charred like the crop remains, identified more or less to species level, and excluding woody fruit/nut taxa that may have been collected resources and would in any case be unlikely to set seed as arable weeds). Since crop processing does not appear to bias functional weed ecological inferences of management intensity (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Jones and Charles2005), samples of crop products, by-products, and mixtures of the two are considered together here.

Results

Crop δ13C and δ15N values

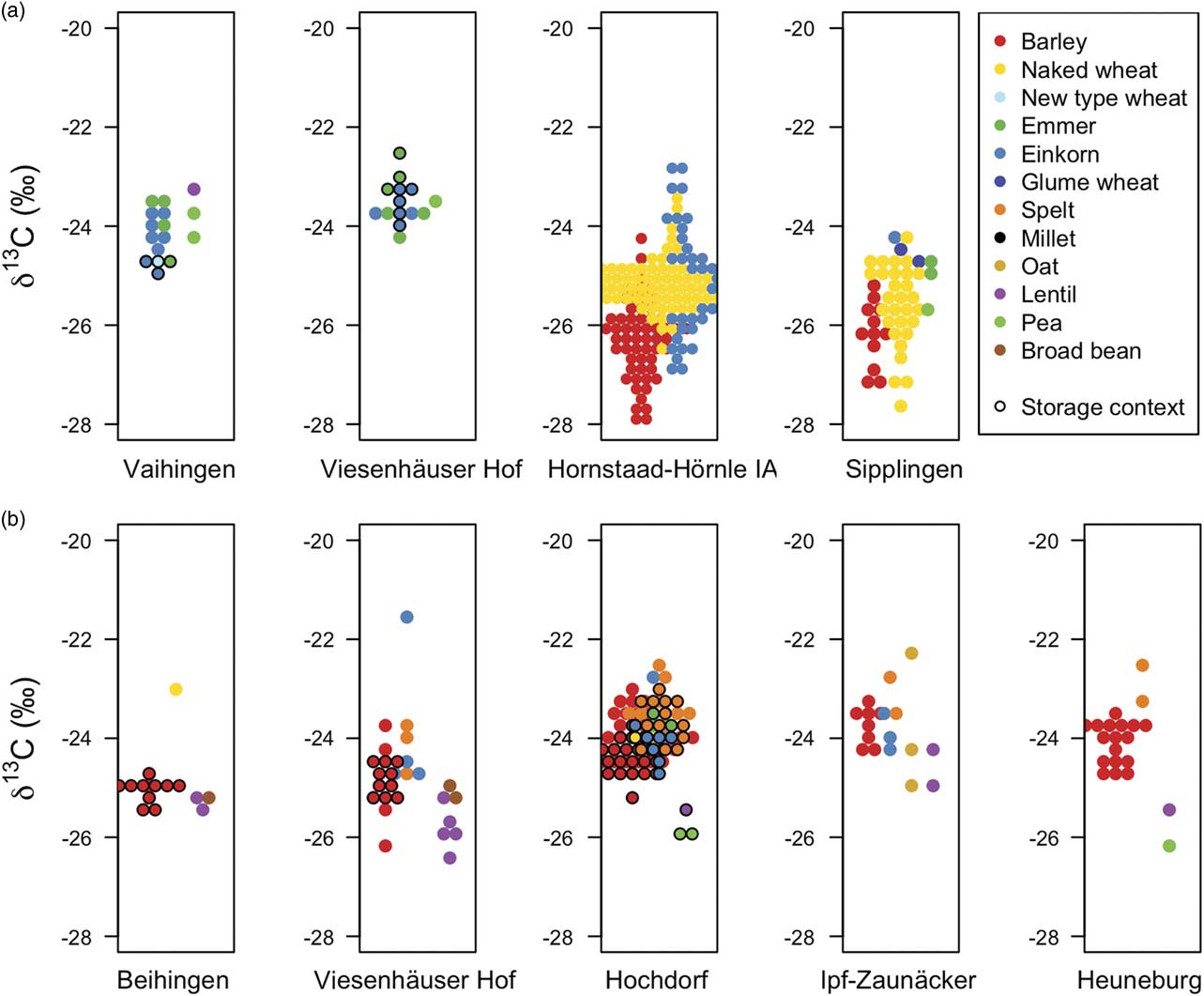

The δ13C values of charred cereal grains and pulse seeds, categorised into barley, wheats, oat and pulses, are shown in Figure 2 and given in Appendix S.5. For detailed results of the statistical analyses, see Table 2. Higher δ13C values tend to reflect less shaded and/or drier growing conditions (Farquhar & Richards Reference Farquhar and Richards1984; Bonafini et al. Reference Bonafini, Pellegrini, Ditchfield and Pollard2013). A linear mixed-effects model shows that the δ13C values of barley grains are 0.8‰ lower than wheat grains (Table 2: 24). This difference is in line with modern studies showing that barley grown in the same watering conditions as wheat will tend to have a lower δ13C value (eg, Ferrio et al. Reference Ferrio, Araus, Buxó, Voltas and Bort2005; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Jones, Charles, Fraser, Halstead, Heaton and Bogaard2013). This suggests that barley and wheat were generally grown in similar watering conditions at all of the sites. The relatively low δ13C values of cereals growing at Hornstaad-Hörnle IA and Sipplingen on the shores of Lake Constance suggest that these crops were grown in shadier conditions, and potentially on wetter soils, than other sites. A heavily wooded environment has been reconstructed from pollen analysis (Maier Reference Maier1999), and therefore it is likely that some of these cereal fields were indeed shaded.

Fig. 2 Carbonised cereal grain and pulse seed δ13C values from a) Neolithic and b) Early Iron Age sites. High δ13C values tend to reflect less shaded and/or drier growing conditions

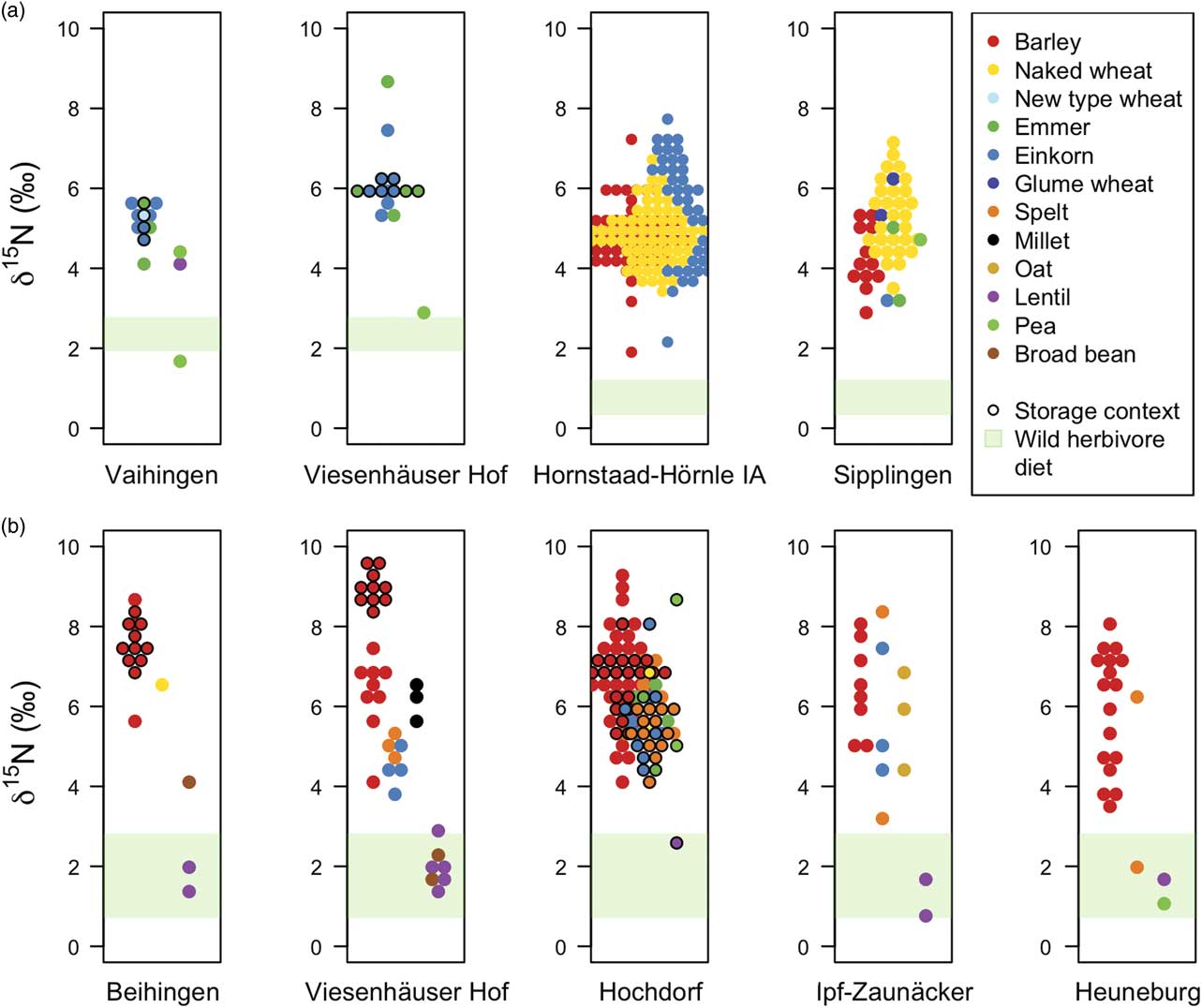

The δ15N values of charred cereal grains and pulse seeds from Neolithic and Early Iron Age sites in south-west Germany, categorised into barley, wheats, oat, and pulses, are shown in Figure 3 (and given in Appx S.5). Higher δ15N values indicate higher inputs of organic matter/manure and the green shading represents the estimated range of δ15N values of (unmanaged) cereals growing without additional organic matter/manure inputs (see section: Estimating a δ 15 N baseline for unmanaged plants from herbivore bone collagen δ 15 N values for more details). At all sites, dating to both the Neolithic and Early Iron Age, the vast majority (>99%) of determined cereal grain δ15N values are higher than the maximum estimated unmanaged cereal grain δ15N. For detailed results of the statistical analyses, see Table 2.

Fig. 3 Carbonised cereal grain and pulse seed δ15N values from a) Neolithic and b) Early Iron Age sites. Higher δ15N values indicate higher inputs of organic matter/manure and the green shaded zone denotes the possible δ15N values of unmanaged (ie unmanured) cereals grains, estimated from wild herbivore bone collagen δ15N values

A mixed effects model shows that Early Iron Age cereal grain δ15N values are on average 1.2‰ higher than those from the Neolithic (Table 2: 26). There is also a large range in cereal grain δ15N values (1.9–9.6‰) at all Iron Age sites, and the variance in cereal grain δ15N values is greater than in the Neolithic (Table 2: 18). For the Early Iron Age, a mixed effects model shows that barley δ15N values are on average 1.3‰ higher than wheats (Table 2: 27). There is a statistically significant difference in barley δ15N values between Early Iron Age sites (Table 2: 16) with Tukey post hoc tests revealing that the significant difference is between barley from the Heuneburg and barley from the rural sites of Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof (p <0.004). This difference is due to the particularly high δ15N values of barley samples from storage contexts at Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof (Fig. 3). When these samples are removed from the analysis, there is no significant difference between barley δ15N values at any of the sites (Table 2: 17). A mixed effects model shows that the δ15N values of pulses are lower than cereals (Table 2: 28), but there is one pea sample from a storage context in Hochdorf that has a δ15N value of over 8‰.

Faunal δ13C and δ15N values

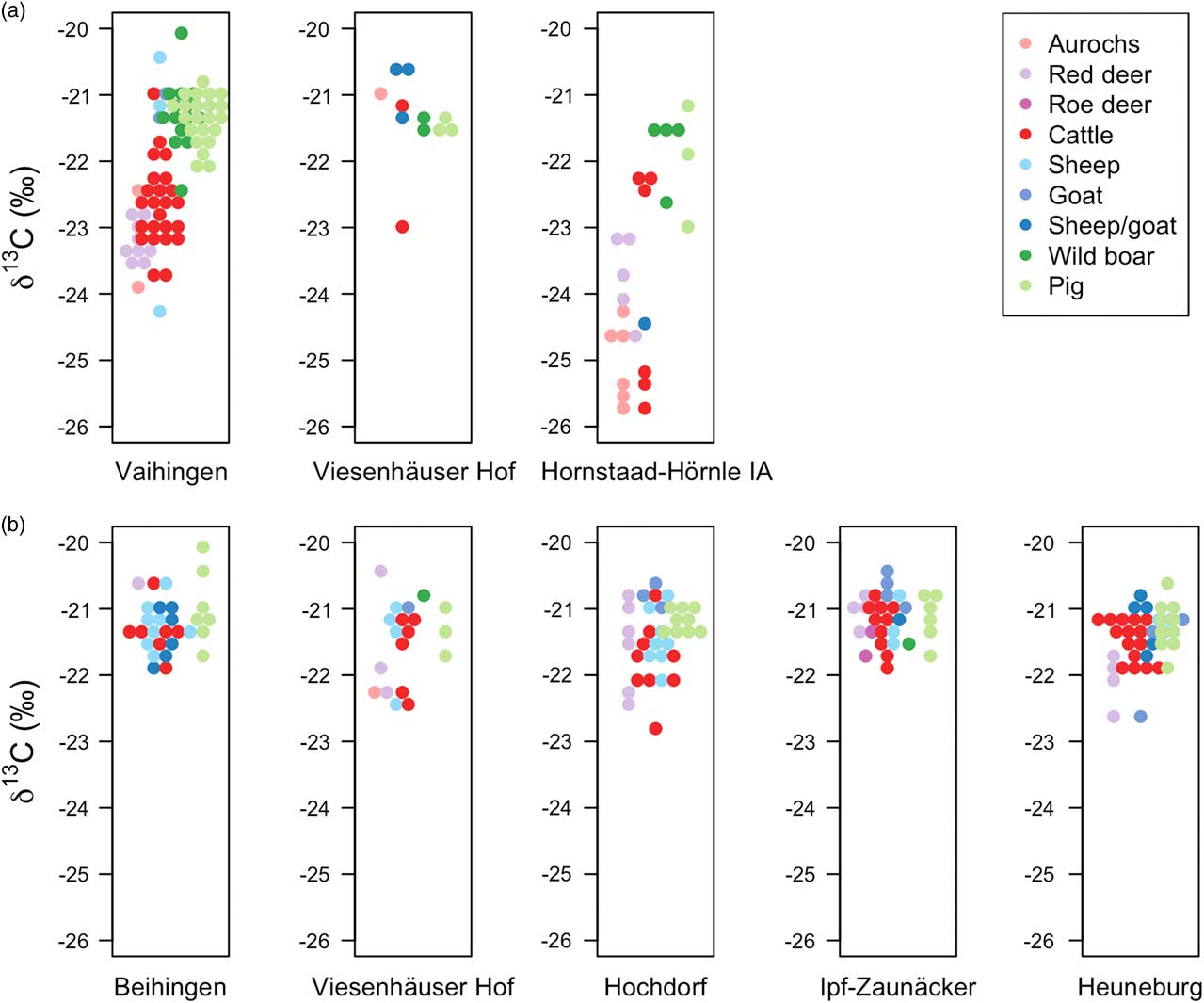

The δ13C and δ15N values of faunal bone collagen, categorised into wild herbivores, domestic herbivores, wild boar, and domestic pigs, are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively (and given in Appx S.6). Higher δ13C values reflect consumption of plants growing in less shaded and/or drier growing conditions (Farquhar & Richards Reference Farquhar and Richards1984; Bonafini et al. Reference Bonafini, Pellegrini, Ditchfield and Pollard2013). Higher δ15N values reflect consumption of plants with higher δ15N values (ie due to manuring) or consumption of meat (in the case of omnivores). A mixed effects model shows that wild herbivore δ13C values at Vaihingen are on average 1.7‰ lower than at Early Iron Age sites (Table 2: 25). Hornstaad-Hörnle IA was not considered in this comparison because it is located in a different environmental setting from the Early Iron Age sites and the wild herbivores have significantly lower δ13C values than at Vaihingen (Table 2: 1). The single wild herbivore δ13C value from Viesenhäuser Hof was not considered. There is no difference between domestic herbivore and wild herbivore δ13C values at any of the Early Iron Age sites (Table 2: 5, 7, 9) apart from the Heuneburg (Table 2: 11), where the δ13C values of wild herbivore bone collagen are significantly lower than those of domestic herbivores. Wild herbivore bone collagen δ13C values are also lower than those of domestic herbivores at Early Neolithic Vaihingen (Table 2: 3).

Fig. 4 Faunal bone collagen δ13C values from a) Neolithic and b) Early Iron Age sites. Higher δ13C values reflect consumption of plants growing in less shaded and/or drier growing conditions

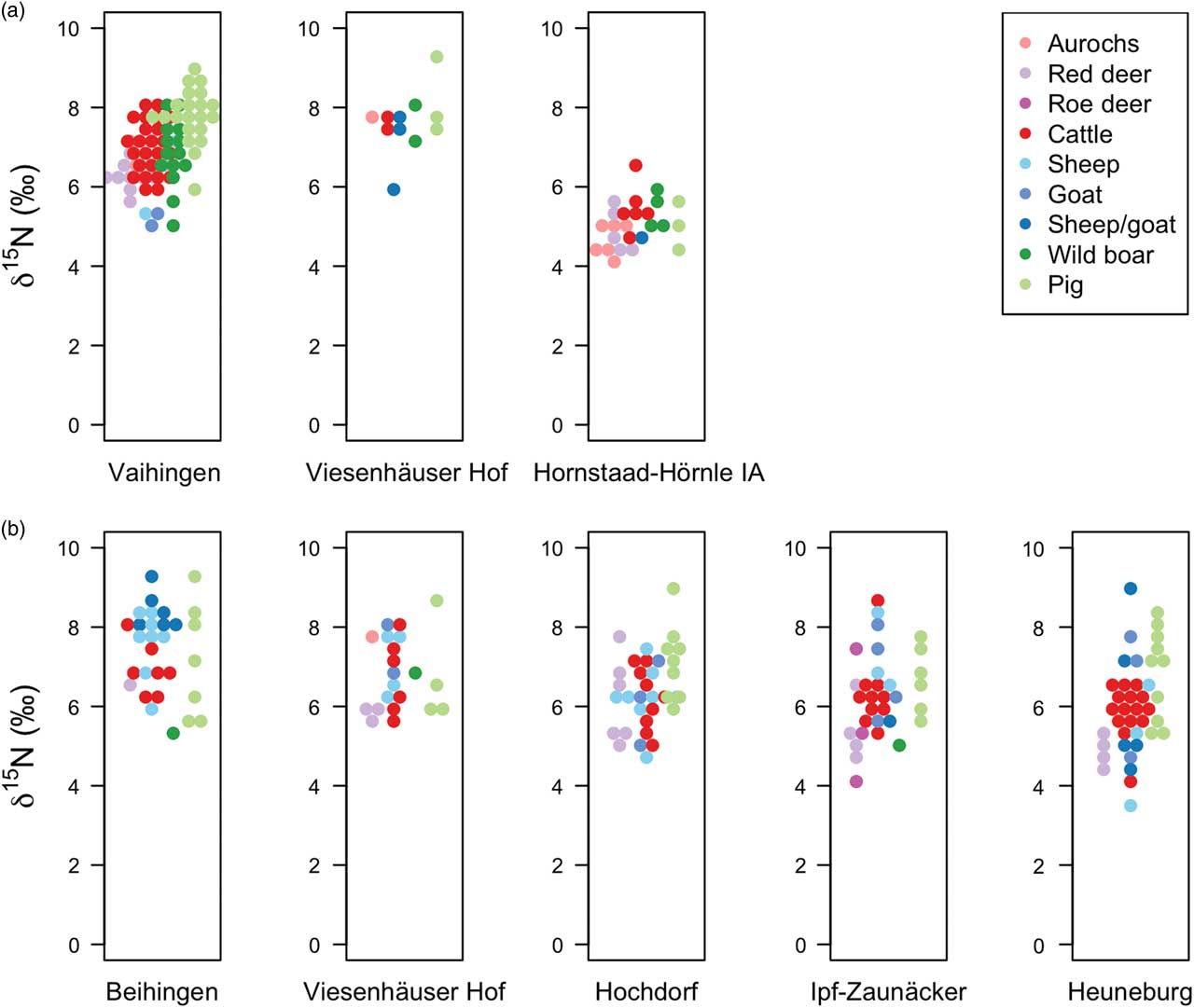

Fig. 5 Faunal bone collagen δ15N values from a) Neolithic and b) Early Iron Age sites. Higher δ15N values reflect consumption of plants with higher δ15N values (ie due to manuring) or consumption of meat (in the case of wild boar and pig)

Domestic herbivores from Early Neolithic Vaihingen have significantly higher bone collagen δ15N values than those of wild herbivores (Table 2: 4). There is no significant difference between wild and domestic herbivore δ15N values at Early Iron Age Viesenhäuser Hof (Table 2: 6) and Hochdorf (Table 2: 8), but domestic herbivores have significantly higher δ15N values than wild herbivores at Ipf-Zaunäcker (Table 2: 10) and the Heuneburg (Table 2: 12). There is also a difference in the variance of sheep/goat and cattle δ15N values at Ipf-Zaunäcker (excluding cattle outlier with δ15N of 8.8‰; Table 2: 22) and the Heuneburg (Table 2: 23), with sheep/goats exhibiting a larger variance in δ15N values than cattle. There is no significant difference in the variance of sheep/goat and cattle δ15N values at Beihingen (Table 2: 19), Viesenhäuser Hof (Table 2: 20), or Hochdorf (Table 2: 21). The mean δ15N value of sheep/goat bone collagen is 1.1‰ higher than that of cattle at Beihingen (Table 2: 13), but there is no difference in sheep/goat and cattle δ15N values at the other Early Iron Age sites.

Appendix S.7 shows the δ13C and δ15N values of faunal bone collagen alongside those of crops and shaded ellipses representing the expected distribution (mean ± 1 and 2 standard deviations) of δ13C and δ15N values of herbivores consuming various dietary combinations of wild plants, cereal rachis (chaff), and cereal grain. While a diet comprising entirely of cereal rachis/grain is not physiologically possible, the fact that domestic cattle at Vaihingen plot closer to the ellipse corresponding to 100% consumption of cereal rachis than wild herbivores suggests that a contribution of rachis to the cattle diet could account for the significant difference in the δ15N values of wild and domestic herbivores at this site (Table 2: 4). Similarly, the variation in δ13C and δ15N values of domestic herbivores at the Iron Age sites could be accounted for by varying proportions of wild plants and cereal chaff in their diets.

Summary of results

To summarise, the δ15N values of cereal grain samples dating to the Early Iron Age are higher than those dating to the Neolithic but are also more variable. The δ13C values of faunal bone collagen are also higher in the Early Iron Age compared to Neolithic Vaihingen, and there is no difference in the δ13C values of wild and domestic herbivores, except for at the Heuneburg. At Early Iron Age Viesenhäuser Hof and Hochdorf, both situated on very fertile soils, there is no difference in the δ15N value of wild and domestic herbivore bone collagen, or the variance in δ15N values of sheep/goat and cattle bone collagen. This contrasts with the difference in δ15N values of wild and domestic herbivore bone collagen and the variance in δ15N values of sheep/goat and cattle bone collagen at Early Iron Age Ipf-Zaunäcker and Heuneburg, which are situated on less fertile soils.

Functional weed ecological attributes

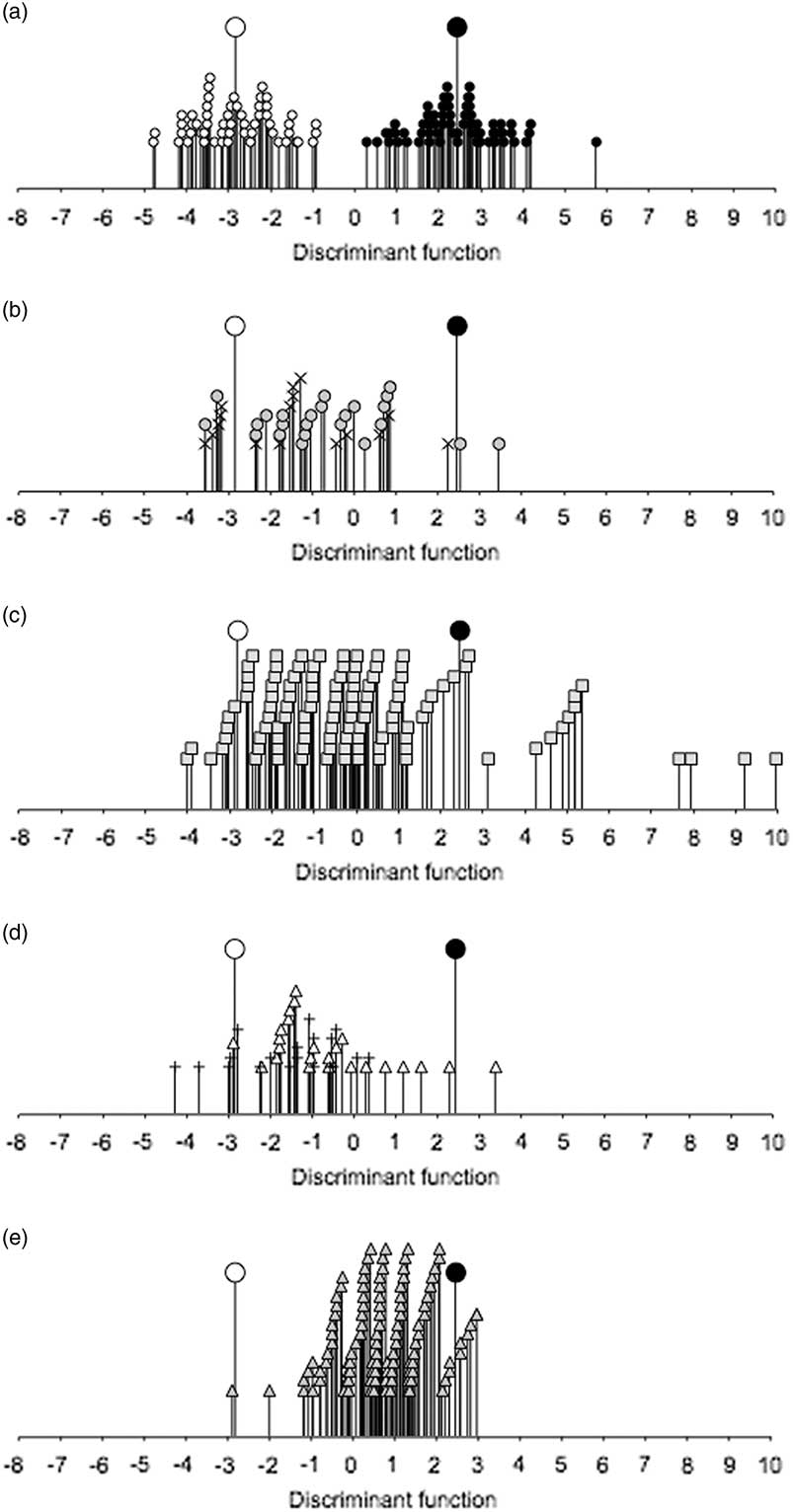

Figure 6a shows the relationship of surveyed present-day fields managed with low-intensity cultivation in Provence, France and high-intensity cultivation in Asturias, Spain to the discriminant function extracted to distinguish between these regimes on the basis of semi-quantitative (presence/absence) weed attribute scores, using five functional attributes relating to soil fertility and disturbance (Appx S.1) as discriminating variables (cf. Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016). The discriminant function was used to classify archaeobotanical samples from Neolithic sites in south-west Germany (Fig. 6e); the Early Iron Age ‘rural’ sites of Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof (Fig. 6b); Hochdorf (Fig. 6c); and Ipf-Zaunäcker and the Heuneburg (Fig. 6d). There is a general trend towards decreased agricultural intensity (lower soil fertility and less disturbance) between the Neolithic and the Early Iron Age (mean discriminant score=0.66 and –0.40, respectively). There is no clear difference in the discriminant scores among Early Iron Age sites, but there is a small number of samples (mostly cereals) from Hochdorf that fall at the highly fertile and disturbed end of the spectrum – more intensive than any of the Neolithic samples.

Fig. 6 The relationship of samples from a) present-day traditionally managed plots in Provence, France (open circles, n=56) and Asturias, Spain (filled circles, n=65); b) Early Iron Age Beihingen (crosses, n=16) and Viesenhäuser Hof (grey circles, n=24); c) Early Iron Age Hochdorf (n=113); d) Early Iron Age Ipf-Zaunäcker (vertical crosses, n=19) and Heuneburg (open triangles, n=24); and e) Neolithic sites in south-west Germany (n=141) to the discriminant function extracted to distinguish between intensive and extensive agricultural regimes on the basis of semi-quantitative (presence/absence) weed attribute scores. Larger symbols indicate centroids for high-intensity (black) and low-intensity (white) regimes

The contrast between the Provence and Asturias agrosystems is dominated by a difference in soil fertility, with disturbance as a secondary factor (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016). This is reflected by the fact that canopy size dimensions, which are correlated positively with fertility and negatively with disturbance (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Hodgson, Nitsch, Jones, Styring, Diffey, Pouncett, Herbig, Charles, Ertuğ, Tugay, Filipovic and Fraser2016, table 3), are strongly correlated with the discriminant function (Appx S.1), while duration of the flowering period (a measure of disturbance tolerance) is only weakly correlated with the function. When the discriminant analysis is performed using canopy diameter and height only as discriminating variables, the two modern agrosystems are less clearly separated (Appx S.8). On this discriminant function the contrast between the Neolithic and Iron Age samples is much reduced (Appx S.8) compared with the analysis based on the full suite of functional attributes (Fig. 6), and in fact their mean discriminant scores are virtually the same (mean discriminant score=0.52 and 0.51, respectively). The implication is that the contrast between the Neolithic and Iron Age is more evenly balanced between soil fertility and disturbance as causal variables than that between the agrosystems in Provence and Asturias. In other words, Iron Age fields tended to be less disturbed and less fertile than Neolithic fields.

Discussion

Crop cultivation

It is unlikely that the high cereal grain δ15N values from Neolithic and Early Iron Age sites are caused by recent forest clearance and burning, since the archaeobotanical weed assemblages are consistent with continuous cultivation (Maier Reference Maier1999; Bogaard Reference Bogaard2004; Stika Reference Stika2009; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010); for ongoing debate over the interpretation of especially off-site Alpine foreland data, see Rösch (Reference Rösch1990), Jacomet (Reference Jacomet2008), and Jacomet et al. (Reference Jacomet, Antolin, Akeret, Bogaard, Baum, Brombacher, Bleicher, Ebersbach, Heitz-Weniger, Hüster-Plogmann, Gross, Kühn, Rentzel, Schibler, Steiner and Wick2016). We have determined the nitrogen isotope values of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) grains grown on plots recently cleared of forest in south-west Germany (harvested in July 2011; see Ehrmann et al. Reference Ehrmann, Biester, Bogenrieder and Rösch2014) and these show that, although wheat grown on plots cleared by burning has higher δ15N values than wheat grown on plots cleared without (–1.1‰ and –4.9‰, respectively), the wheat grain δ15N values are still much lower than those determined for the archaeological cereal grains from the sites in this study. The particularly low δ15N values of plants growing in recently cleared woodland are likely due to acidic soils (pH 4–6 for the experimental plots), which inhibit ammonia loss (Nadelhoffer & Fry Reference Nadelhoffer and Fry1994), and low rates of nitrogen cycling in forest soils due to lack of disturbance (Mariotti et al. Reference Mariotti, Pierre, Vedy, Bruckert and Guillemot1980; Hobson Reference Hobson1999). It is also unfeasible that denitrification caused by waterlogging is the cause of the high δ15N values, since plants indicative of wet growing conditions are not prevalent among the crop weeds (Maier Reference Maier1999; Stika Reference Stika2009; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010) and soil surveys in the vicinity of all of the sites have revealed well-drained soils that would have been suitable for agriculture (Maier Reference Maier1999; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010; Baum Reference Baum2014). It is therefore most likely that the relatively high cereal grain δ15N values are due to addition of 15N-enriched manure/organic matter.

The high δ15N values of cereal grains from the Early Iron Age compared to those from the Neolithic suggest that high levels of manuring, or other organic matter inputs (eg, middening/composting), were maintained or increased during the Iron Age compared to the Neolithic. Since it is possible that 15N could build up in the soil if manure is added over thousands of years, it is difficult to say for certain whether higher cereal grain δ15N values were caused by higher levels of manuring in the Early Iron Age compared to the Neolithic. However, the level of manuring clearly did not decrease significantly. More widespread use of animal traction in the Early Iron Age, as attested by mortality profiles (Schatz & Stephan Reference Schatz and Stephan2008), would have facilitated the distribution of this heavy resource over a wider area (cf. Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2011). Pulse δ15N values much higher than the δ15N value of atmospheric-N (0‰) indicate that they were also grown in intensively manured soil (>70t manure/ha; Treasure et al. Reference Treasure, Church and Gröcke2016), perhaps in small plots together with heavily manured garden crops.

The large range in Early Iron Age cereal δ15N values indicates wide variation in manuring levels between cultivation plots, which could reflect an extended gradient in manuring intensity due to the greater distance between settlements and animal penning areas within a larger agricultural hinterland. This variation also suggests small-scale decision-making regarding manure use. Taken alone, the δ15N values suggest that crop cultivation was equally, if not more, labour- and resource-intensive as during the Neolithic. This does not correspond with an agricultural system where the predominant crops of barley and spelt wheat were grown on a large scale under low input conditions for remobilisation to fortified hilltop sites.

Despite the higher δ15N values of cereals, which seem to indicate increased manuring, the functional weed ecology shows that net soil fertility decreased in the Early Iron Age, and that soil disturbance levels clearly decreased as well. The lack of evidence for increasing soil fertility could indicate that nutrients were not being replenished sufficiently to replace those being removed during successive harvests, perhaps exacerbated by harvesting crops closer to the ground, thereby reducing the plant matter returned to the soil (cf. Willerding Reference Willerding1986, 319; Rösch Reference Rösch1998). Alternatively, it could reflect the expansion of cultivation onto less fertile soils around the Early Iron Age settlements – at least less fertile than the prime loess and luvisols on which the Neolithic sites in this study were situated – and/or erosion of soils due to more widespread use of the plough (cf. Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010). Ard ploughing, if accompanied by little to no manual cultivation, would have led to less intensive turnover of the soil (Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2011; Halstead Reference Halstead2014, 44) and thus lower soil disturbance. An expansion in fallow land for animal grazing could also have contributed to the general trend towards lower disturbance in the Early Iron Age. The weed evidence could thus accommodate the Feld-Graswirtschaft (rotation of annual crops with grass ley pasture) system proposed by Stika (Reference Stika2009), who identified high proportions of weed species characteristic of a grassland ecosystem in the weed assemblage at Hochdorf. Grazing of animals on fallow land would also have contributed low-level manuring, although no modern studies have yet determined the effect on crop δ15N values as a result of this practice.

The wide range of functional weed ecology discriminant scores at Early Iron Age sites, particularly at Hochdorf, indicates large variation in soil fertility and disturbance between different plots and mirrors the high variability in manuring intensity. The samples from Hochdorf (mainly associated with cereal grains) with particularly high discriminant scores could originate from intensively worked garden plots, evidence for which comes from postholes that may have marked plot boundaries (Biel Reference Biel2015, 50). Taken together, the isotope and weed ecological evidence suggest that surplus cereal production in the Early Iron Age was achieved through sustained use of manure on larger (potentially more marginal) cultivated areas, enabled by more widespread use of the ard plough and animal traction, but that there was considerable variation in labour and manure inputs between plots. There is no evidence for large-scale, low-input cultivation of selected crops or a clear distinction in cultivation practices between rural and fortified hilltop sites that could be indicative of elite intervention in production.

In the Neolithic, there were signs that different crops received differing quantities of manure, potentially according to social or economic status. For example, at Late Neolithic Sipplingen, naked six-row barley had consistently lower δ15N values than naked wheat throughout 1000 years of [intermittent] occupation, and when emmer replaced naked wheat as the most ubiquitous cereal, its δ15N values increased, indicating a switch of investment according to economic importance (Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a). This trend is perpetuated in the Early Iron Age: hulled six-row barley was the most ubiquitous crop and it has significantly higher δ15N values than the wheats. Manuring is currently our best explanation for differential enrichment of crop 15N, though other factors (eg, soil type, topography) could have amplified (or reduced) husbandry differences. Moreover, since we know that crop δ15N values reflect long-term land use history (manuring must be sustained for years before crop δ15N values increase; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Bogaard, Heaton, Charles, Jones, Christensen, Halstead, Merbach, Poulton, Sparkes and Styring2011), this means that barley was grown on plots that were cultivated under different conditions for many years. While preferential manuring of hulled barley at all of the Early Iron Age sites (despite variability in manuring practice in general) could be because it responds particularly well to manuring (Viklund Reference Viklund1998, 139), extrapolation of crop ecology from modern varieties is problematic. It therefore seems plausible that the tendency towards higher barley δ15N values reflects its economic importance as a crop in the Early Iron Age. More broadly then, the distinctive growing conditions of barley could be linked to the wider cultural importance of beer (eg, Dietler Reference Dietler1990; Sherratt Reference Sherratt1997): germinating barley grains have been found in what are identified as malting ditches (Feuerschlitze) for beer brewing at the settlement of Hochdorf (Stika Reference Stika2009). Though barley undoubtedly had other uses in addition to beer brewing, its association with such a prestigious activity may well have shaped the way it was cultivated.

If large quantities of hulled barley and spelt wheat were indeed cultivated in rural settlements and then exported to fortified hilltop sites like the Heuneburg (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010), the only indication of differential access to crops comes from the high δ15N values of hulled barley grains found in stored caches in the rural settlements of Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof. Though these particular sites are too far from the Heuneburg to have been the source of its imported crops, the stored caches at Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof suggest that particularly intensively manured crops were retained in rural settlements. The isotope values of cereals and pulses from storage deposits also allow understanding of how crops from different plots were distributed and used within settlements. In the Neolithic, the small variation in δ15N values of multiple wheat grain samples from storage contexts at Viesenhäuser Hof and Hornstaad-Hörnle IA (0.2‰ and 0.5‰, respectively) suggests that grains grown under similar growing conditions, and potentially from the same plot, were stored together. This is consistent with a household level of production and storage, whereby individual households made their own decisions about the amount of manure to add and retained their own crops for consumption. The small variation in δ15N values of multiple hulled barley grain samples from storage contexts at the Early Iron Age rural sites of Beihingen and Viesenhäuser Hof (0.5‰ and 0.4‰, respectively) suggests that a similar method of production was practised here.

In contrast, there is much larger variation in δ15N values of multiple hulled barley samples from one of the two ‘malting ditches’ at Hochdorf (0.9‰), which suggests that barley for malting was collected from a wider range of growing conditions. This is unsurprising given the huge quantities of barley grains – thousands of kilograms – that would have been required (Stika Reference Stika2009). Such variation implies that individual households, cultivating their own plots and making their own decisions about manuring practices, were contributing a portion of their harvest to beer production. The importance of drinking in Early Iron Age society (Dietler Reference Dietler1990; Reference Dietler2006; Stika Reference Stika1996) plausibly reflects the value of social relationships in acquiring political status. This perspective is similar to that developed for Early Iron Age hillforts in southern England, where storage pits and associated grain-rich fills suggest mobilisation of surplus for consumption and feasting at fortified hilltop sites and demonstrate the importance of these events in attaining and enhancing political power (van der Veen & Jones Reference van der Veen and Jones2006).

Landscape use

The expansion of fallow land for animal grazing – suggested by the grassland habitat of many weed species (Stika Reference Stika2009), and consistent with the trend in functional weed ecological attributes towards decreased soil disturbance – likely reflects an ‘opening-up’ of the Early Iron Age landscape for larger scale crop and animal husbandry. This is also supported by an increase in herbivore δ13C values compared to the Neolithic. Higher herbivore bone collagen δ13C values indicate that the plants eaten by herbivores were growing in less shaded conditions, caused by a decrease in the prevalence of closed canopy woodlands (Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Bridault, Hobson, Szuma and Bocherens2008; Bonafini et al. Reference Bonafini, Pellegrini, Ditchfield and Pollard2013). In addition, the lack of a significant difference between the δ13C values of wild and domestic herbivores, at all Early Iron Age sites apart from the Heuneburg, indicates that red and roe deer were feeding in similarly open landscapes to cattle, sheep and goats. The increase of pasture and meadowland has been suggested on the basis of pollen evidence at a number of locations in south-west Germany (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010), but the δ13C values of herbivores found at the archaeological sites provide a direct measure of the openness of the landscape around these settlements in the Early Iron Age.

Animal husbandry

Domestic livestock evidently played an integral role in the agricultural economy of the Early Iron Age, providing manure used in crop cultivation, traction for its transportation and for ploughing arable fields. The increase in grassland pastures in the Iron Age indicates an increased demand for grazing land, probably due to greater numbers of livestock. Higher numbers of domestic livestock presumably supplied the large quantities of manure suggested by the high cereal grain δ15N values from the Early Iron Age. Slightly higher δ15N values of domestic compared to wild herbivore bone collagen at Ipf-Zaunäcker and the Heuneburg could result from a small contribution of manured plants/crops/crop residues to the domestic herbivore diet. This could be due to grazing of herbivores on fallow land, resulting in low-level manuring and subsequent increase of herbivore bone collagen δ15N values due to ingestion and assimilation of manured vegetation, and/or grazing on young cereal plants (to prevent lodging) or on cereal stubble after the harvest (Appx S.7 shows that cereal rachis could indeed have made a contribution to the herbivore diet). The larger variation in sheep and goat δ15N values compared to cattle δ15N values at these sites could reflect household- or kinship-level control of small animal herds, so that different herds had access to fields with differing land use histories. The contrasting consistency of cattle δ15N values could indicate large-scale herding of cattle by specialised herders who allowed cattle access to more-or-less the same range of vegetation. Both Ipf-Zaunäcker and Heuneburg have relatively infertile soils in their vicinity, which has led to the hypothesis that they were centres for livestock rather than cereal production (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010). Perhaps in these settlements, the lower density of arable fields allowed more local pasturing of the smaller ruminants. At the Heuneburg, the significant difference in the δ13C values of wild and domestic herbivores also indicates that there were still some wooded areas where wild herbivores could browse. Strontium isotope values of cattle, sheep/goat, and pig teeth from Ipf-Zaunäcker and the Heuneburg also indicate that livestock were pastured locally, but that cattle and pigs were occasionally imported from further afield in the Black Forest (Stephan Reference Stephan2009).

The high quality soils in the immediate vicinity of Viesenhäuser Hof, Hochdorf, and Beihingen suggest that most of the surrounding area was permanently cultivated with barley, wheat and legumes (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Rösch, Sillmann, Ehrmann, Liese-Kleiber, Voigt, Stobbe, Kalis, Stephan, Schatz and Posluschny2010). The lack of difference in δ15N values between wild and domestic herbivores at Viesenhäuser Hof and Hochdorf suggests that livestock herds at these sites did not have systematic access to plants with higher δ15N values, via consumption of manured fodder or grazing on manured arable/fallow fields. Also at these sites, there is no significant difference in the variance of sheep and goat and cattle bone collagen δ15N values, suggesting that sheep, goats, and cattle were all herded in similar environments. To some extent this supports the strontium isotope results of cattle, sheep/goat, and pig teeth from Hochdorf, whose high variability indicates that they were all pastured in a range of similar areas of Keuper sandstone, which occurs in small areas close to the settlement and in larger areas 15–30 km away (Stephan Reference Stephan2009; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Knipper, Schatz, Price and Hegner2012). Although there is no clear evidence of stalls within the settlements, it is plausible that the animals would have been penned overnight, allowing collection of their manure for spreading on the fields.

Conclusion

This is the first time that crop and faunal isotope values and functional weed ecological attributes have been combined in a regional study of past agricultural practice. While crop δ15N values reveal differences in manuring practice between plots and crop species, and weed functional attributes reflect site-level trends in soil fertility and disturbance, this study has shown that together they can provide a more nuanced insight into past farming practice, belying assumptions that higher crop δ15N values necessarily reflect higher soil fertility. While this is the case for the intensive ‘garden’ cultivation practiced in the Neolithic, by the Early Iron Age it seems that high manuring levels were required merely to maintain soil fertility rather than to enhance it, perhaps due to new harvesting methods that cut crops closer to the ground and as the result of thousands of years of continuous cultivation. Moreover, there is no evidence that the proliferation of animal traction and the ard plough through the later Neolithic caused a revolution in agricultural practice (cf. Styring et al. Reference Styring, Maier, Stephan, Schlichtherle and Bogaard2016a), as evolutionary models of agricultural development envisage (eg, Boserup Reference Boserup1965). Instead, it seems that more widespread use of the ard plough eased the human labour costs of ‘intensive’ agriculture and made it viable on a larger scale – a form of extensification but without a dramatic decrease in labour inputs per unit area (cf. Isaakidou Reference Isaakidou2011). The Early Iron Age crops generally align more closely with low-intensity cultivation than those of the Neolithic in south-west Germany, which in conjunction with the pollen evidence for more open anthropogenic landscapes suggests modest extensification. On the other hand, there is no evidence for large-scale and low-input cultivation of selected crops that might be consistent with elite intervention in production. Rather, the isotope results provide insight into the variability in crop and animal husbandry practices – from differences in manuring between the barley intended for local consumption and that for redistribution at rural sites to differences in herding practice between sites with fertile and less fertile soils. This demonstrates the diverse strategies that people employed to meet production needs, in response to local conditions and preferences. Despite this variation, there was a consistent decision to allocate more manure to barley, the core ingredient of beer brewing, underlining the pervasive importance of beer in Early Iron Age society. These findings also support the idea of the central role of feasting and drinking in negotiating political power in the Early Iron Age (cf. Dietler Reference Dietler1990; van der Veen & Jones Reference van der Veen and Jones2006). Our ecological perspective on farming and herding practice thus extends discussion of elite consumption practices and their role in centralisation in Early Iron Age central Europe.

Acknowledgements: The work reported here was funded by the European Research Council (AGRICURB project, grant no. 312785, PI: Bogaard). AB and AS designed the research, AS and AB drafted the paper, MR, MS, EF and HS contributed botanical material, data, and discussion of the results, and ES contributed faunal material, data, and further discussion. The functional attribute data used in this study draws upon a database compiled by John Hodgson and part-funded by NERC grant NER/A/S/2001/01047 (PI: Michael Charles). We would also like to thank Rebecca Fraser for isotope analysis of the faunal bone collagen from Hornstaad-Hörnle IA (NERC standard grant NE/E003761/1, PI: Bogaard), Otto Ehrmann for providing bread wheat grains from the Forchtenberg experiment for nitrogen isotope analysis, and Corina Knipper for access to the faunal isotope data from Neolithic Stuttgart-Mühlhausen Viesenhäuser Hof. We are grateful to Caroline Montrieux and Edward Wilman for processing archaeobotanical samples and faunal bone collagen for isotope analysis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2017.3