Nutrition support

Nutrition support involves the provision of nutrition beyond that provided by normal food intake using oral supplementation, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition(1). The goals of nutrition support are to ensure the attainment of an individual's nutritional requirements. Oral nutrition using special diets and supplements is usually considered the first-line therapy in managing malnutrition; however, certain individuals may require enteral or parenteral nutrition when oral intake is reduced or when swallowing is unsafe(Reference Kurien, Penny and Sanders2). Of these modalities, enteral nutrition is usually preferred in the context of a normally functioning gastrointestinal tract as it is physiological, cheaper and may help maintain gut barrier function(Reference Buchman, Moukarzel and Bhuta3,Reference Braunschweig, Levy and Sheean4) .

Most patients requiring nutrition support therapy have treatment for less than 1 month(Reference Pearce and Duncan5). When short-term enteral feeding is considered, nasogastric and orogastric tubes are most frequently used, reflecting their ease of insertion and removal (Fig. 1). Tubes range in length and diameter and can be inserted either at the bedside, at endoscopy or using radiological guidance. When nutritional intake is likely to be inadequate for more than 4–6 weeks then enteral feeding using a gastrostomy is most frequently considered(Reference Kurien, McAlindon and Westaby6).

Fig. 1. (Colour online) Methods of enteral feeding.

History of gastrostomies

A gastrostomy describes a feeding tube placed directly into the stomach via a small incision through the abdominal wall. It can provide long term enteral nutrition to patients who have functionally normal gastrointestinal tracts but who cannot meet their nutritional requirements due to an inadequate oral intake(Reference Kurien, McAlindon and Westaby6). Infrequently, they may also be used for decompressing the stomach or proximal small bowel following outflow obstruction or volvulus.

The concept of a gastrostomy was first proposed by Egeberg, a Norwegian army surgeon in 1837, however, it was only in 1876 when Verneuil used silver wire to oppose visceral and parietal surfaces that success was achieved in inserting a surgical gastrostomy(Reference Cunha7). Post-procedural peritonitis was the most frequent limitation to previous attempts at surgical insertion, with death ensuing in individuals who developed this complication. Stamm modified Verneuil's surgical technique in 1894, prior to modifications being developed by Dragstedt, Janeway and Witze in the 20th century(Reference Minard8).

In 1979, Michael Gauderer and Jeffrey Ponsky revolutionised gastrostomy practice by pioneering an endoscopic method of insertion in Cleveland, Ohio(Reference Gauderer, Ponsky and Izant9). The two paediatricians performed the very first percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in a 6-month old child, using a 16 French DePezzar (mushroom tipped) catheter, which they replicated again in a further five paediatric cases(Reference Ponsky10). Ponsky then utilised this technique in a cohort of adult patients with dysphagic strokes, which heightened interest in this novel endoscopic technique(Reference Ponsky10). The ‘pull technique’ that they pioneered is currently one of three endoscopic methods frequently used today in clinical practice. When compared to previously used surgical methods, endoscopic insertion was favourable, as it was minimally invasive and incurred lower morbidity and mortality.

Two years later in 1981, Preshaw in Canada used fluoroscopic guidance to insert the first percutaneous radiological gastrostomy(Reference Preshaw11). Like endoscopic methods, modifications of the original radiological technique have occurred since the original method was conceived. However, despite these advances, endoscopic techniques remain the most popular methods of insertion internationally, with percutaneous radiological gastrostomy insertion most frequently reserved for high-risk patients, oropharyngeal malignancy and when the endoscopic passage is technically difficult(Reference Galaski, Peng and Ellis12,Reference Ozmen and Akhan13) .

Indications for gastrostomy

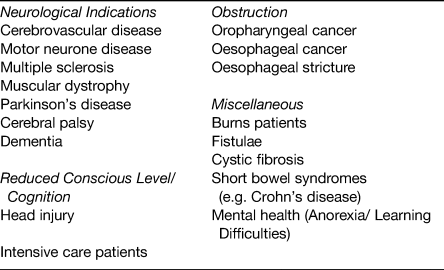

Since the introduction of endoscopic and radiological insertion techniques for gastrostomy, there has been increasing demand for this intervention, for an increasing number of clinical indications. A broad list of indications for which patients are currently being referred for gastrostomy is given in Table 1. Despite being widely performed the evidence base to support gastrostomy feeding in certain patient groups is lacking. This is reflected in the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report, which reviewed mortality outcomes post-PEG insertion between April 2002 and March 2003(14). This identified a 30-d mortality rate in a cohort of 16 648 patients of 6 %(14). Subgroup analysis alarmingly showed that 43 % died within 1 week of undergoing PEG insertion, of whom in 19 % the intervention was felt to have been futile. Concerningly, the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death data identified a high prevalence of acute chest infections (40 %) in those undergoing PEG placements, which could have influenced these mortality outcomes. The role of gastrostomy feeding in different patient subgroups and the evidence that exists to inform clinical decision-making is discussed later.

Table 1. Indications where percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding is considered

Gastrostomy feeding and dementia

Patients with dementia frequently develop feeding problems, leading to weight loss and nutritional deficiencies. Up to 85 % of these problems develop prior to death suggesting that difficulties with feeding are an end-stage problem associated with advanced disease(Reference Mitchell, Teno and Kiely15). Whether or not to use gastrostomies to feed patients with dementia is an emotive and controversial issue. This controversy is further compounded by the fact that in the late stages of the illness, individuals lack the capacity to express their wishes. The 2010 British Artificial Nutrition Survey gives insights into the frequency of insertion for dementia, highlighting that registration of home enteral tube feeding (mainly by gastrostomy) for this indication declined from 7 % in 2004 to 3 % (48/1560)(Reference Jones16). This decline is likely to reflect concerns raised in the medical literature about inserting gastrostomies for this specific indication.

There is currently a limited number of prospective studies examining outcomes in dementia, which could help inform clinical practice(Reference Malmgren, Hede and Karlstrom17,Reference Martins, Rezende and Torres18) . In a retrospective cohort study of 361 patients, mortality was found to be significantly higher in dementia patients compared to any other patient group (54 % 30-d mortality and 90 % at 1 year)(Reference Sanders, Carter and D'Silva19). Our group replicated this finding in a prospectively followed cohort (n 1023), however, the number of insertions performed for the indication of dementia was low (n 5)(Reference Kurien, Leeds and Delegge20). These concerns have been highlighted in a Cochrane systematic review, which showed no improvements in survival, quality of life, nutritional status, function, behaviour or in psychiatric symptoms in patients with advanced dementia receiving enteral tube feeding(Reference Sampson, Candy and Jones21).

There now exists general agreement amongst clinicians that PEG feeding does not benefit people with advanced dementia. The evidence supporting this assertion has been disseminated through guidelines and enhanced education, and influenced the decline in gastrostomy insertions for this indication in the UK over recent years. Although this decline has been seen within the UK, the practice of inserting gastrostomies for this indication remains widespread in other countries(Reference Nakanishi and Hattori22). The reasons for this geographical variation are uncertain but may reflect how factors such as cultural, religious, family and healthcare system expectations influence PEG decision making, which goes beyond clinic outcomes alone. In summary, gastrostomy feeding does not derive benefits to people with advanced dementia.

Gastrostomy feeding in stroke patients

Dysphagia is common in patients after a stroke ranging between 23 and 50 %(Reference Singh and Hamdy23). Neurological recovery does occur in some patients leading to improvements in swallowing function, however many remain at high risk of developing aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition. Enteral nutrition is widely advocated in these individuals; however, controversy exists as to the optimal mode of delivery.

Historically, two small randomised, studies evaluating PEG v. nasogastric feeding demonstrated improved mortality outcomes, hospital length of stay and nutritional indices in patients who had a PEG, suggesting derived benefit(Reference Norton, Homer-Ward and Donnelly24,Reference Park, Allison and Lang25) . More recently, the FOOD (Feed or Ordinary Diet) trial has been published and questioned the potential merits of PEG feeding(Reference Dennis, Lewis and Warlow26). This multi-centre study consisted of three pragmatic randomised controlled trials: Trial 1 aimed to determine whether routine oral nutritional supplementation of a normal hospital diet improved outcomes after stroke; Trial 2 assessed whether early tube feeding improved the outcomes of dysphagic stroke patients; Trial 3 examined whether tube feeding via a PEG resulted in better outcomes than nasogastric feeding. The results from this study showed no benefit from oral supplements; however, survival improved when tube feeding was commenced early but at the cost of poorer functional outcomes. In Trial 3 comparing PEG feeding v. nasogastric feeding, there was a significant difference between the two groups, with PEG fed patients likely to have higher mortality and poorer outcomes. A possible explanation for these findings is the impact of dependency on long-term PEG feeding, with PEG patients still requiring feed during the follow-up period when compared to patients with nasogastric tubes(Reference Dennis, Lewis and Warlow26). Furthermore, survivors in the PEG group had a lower quality of life (based on EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol Group), and were more likely to be living in institutions when compared to nasogastric fed patients(Reference Dennis, Lewis and Warlow26). In summary, enteral nutrition support is useful in patients with dysphagia following an acute stroke, however, the optimal method of delivery (PEG vs. nasogastric feeding) remains uncertain.

Gastrostomy feeding in oropharyngeal malignancy

Patients with oropharyngeal malignancy are at risk of malnutrition due to direct effects from the tumour (e.g. reduced appetite, host response, problems ingesting food due to tumour size) and also from the anticancer therapies themselves (e.g. radiation-induced mucositis). PEG and nasogastric tube insertions are widely performed in this patient group as a prophylactic measure (prior to radiotherapy and chemotherapy), but also when swallowing problems occur directly because of the malignancy itself. Despite the potential merits of enteral feeding in this patient group, there had been limited research evaluating gastrostomy feeding in comparison to other enteral feeding methods(Reference Corry, Poon and McPhee27). This led to a Cochrane review in 2010 concluding that there was insufficient evidence to determine the optimal method of enteral feeding in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy and/or chemoradiotherapy(Reference Nugent, Lewis and O'Sullivan28).

More recently a prospective comparative cohort study from Australia compared no PEG (n 61) v. prophylactic PEG (n 69) in patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemotherapy. Over a 2-year period, prophylactic gastrostomy significantly improved nutritional outcomes and reduced unplanned hospital admissions(Reference Brown, Banks and Hughes29). A randomised controlled trial funded by the National Institute for Health Research) Health Technology Assessment programme had planned to compare gastrostomy and nasogastric feeding in this cohort of patients and advance knowledge in this area; however, poor recruitment limited trial progression(Reference Paleri, Patterson and Rousseau30). In summary, further work is needed to establish when and which enteral feeding routes are most appropriate for this particular group of patients.

Gastrostomy feeding in neurodegenerative disorders

Gastrostomies are increasingly being used in the treatment of patients with neurogenic dysphagia(Reference Britton, Lipscomb and Mohr31). Whilst the exact aetiology of the neurogenic dysphagia is frequently unknown, it is commonly encountered in patients with motor neurone disease, Huntington's chorea, multiple sclerosis and in patients with Parkinson's disease. When bulbar weakness develops leading to dyarthria and dysphagia, gastrostomies are frequently considered to aid nutrition, reduce choking episodes and to minimise the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

PEG feeding is recommended for people with motor neurone disease and dysphagia in both European and American guidelines(Reference Andersen, Abrahams and Borasio32,Reference Miller, Jackson and Kasarskis33) . Despite patients potentially fulfilling criteria for insertion, it is recognised that patients' and caregivers’ perceptions about PEG has an influence on both the timing and proportion that actually receive the intervention(Reference Stavroulakis, Baird and Baxter34). This variability has been subject to a meta-analysis and survey of clinical practice, which highlighted the dearth of high-quality evidence regarding the optimal timing and method of gastrostomy insertion(Reference Stavroulakis, Walsh and Shaw35). This provided the rationale for the recent ProGas study, which was a large, multicentre, longitudinal cohort study(36). This study compared the different methods of gastrostomy and explored the optimal timing for insertion. Findings showed no differences between procedural methods for inserting gastrostomies and limited benefits in those who at the time of gastrostomy had more than 10 % loss of their diagnosis weight. These findings have helped to inform both patients and relevant clinicians about the optimal timing of PEG for people with motor neurone disease. Further work is now needed to establish the benefits derived to people with other neurodegenerative conditions.

Gastrostomy feeding in other patient sub-groups

PEG insertion is undertaken for a number of other indications (shown in Table 1). The evidence supporting its role in some of these differing sub-groups is highly questionable. An example of this is in patients who suffer head injuries following road traffic accidents, falls, violence or sport who are often considered for gastrostomy whilst on intensive care units. Currently, the latest Cochrane review of nutritional support in head injury patients (analysis of eleven trials) suggests early feeding may improve survival and disability, however, this benefit may be best derived from total parenteral nutrition rather than enteral nutrition methods(Reference Perel, Yanagawa and Bunn37). When comparing nasogastric feeding with gastrostomy feeding in this patient group, gastrostomy feeding may reduce pneumonia rates but does not derive any mortality benefit(Reference Kostadima, Kaditis and Alexopoulos38).

Another group of patients seen in adult services with gastrostomies are patients with cerebral palsy. Gastrostomy insertion is increasingly being performed in children with this condition with the aim of improving weight, nutritional indices and quality of life(Reference Dahlseng, Andersen and Daga39–Reference Sullivan, Juszczak and Bachlet41). These individuals are then moved into adult services as they reach adulthood. Unfortunately, as in many other areas of gastrostomy feeding there is a paucity of well-designed randomised controlled trials evaluating gastrostomy feeding in this patient group, leading to uncertainty regarding the merits of this intervention(Reference Sleigh, Sullivan and Thomas42). This uncertainty is reflected in other conditions (anorexia nervosa, achalasia, frailty, burns patients) and highlights the need for well-conducted studies, to help better inform clinical practice.

Gastrostomy feeding and nutritional outcomes

Feeding via a gastrostomy

Enteral feeds can be delivered via gastrostomies using continuous, bolus or intermittent infusion methods(Reference Kirby, Delegge and Fleming43). These feeds are nutritionally complete (containing protein or amino acids, carbohydrate, fat, water, minerals and vitamins) and are available in fibre-free and fibre-enriched forms. Determining the type of feed used is influenced by an individual's preferences/lifestyle, nutritional requirements, gastrointestinal absorption, motility and also by their co-morbidities, such as renal or liver disease(Reference Stroud, Duncan and Nightingale44). Continuous infusion provides patients with feed over 24 h. It is most frequently reserved for patients with high gastric residual volumes on intensive care units, and those having a history of aspiration, vomiting and/or reflux(Reference Marks and Ponsky45). This regimen is associated with an increased risk of drug–nutrient interactions and may also increase intragastric pH leading to bacterial overgrowth(Reference Kurien, Penny and Sanders2). Bolus feeding describes the delivery of 200–400 ml of feed periodically throughout the day. It permits medications to be given at times different to feeds and also gives patients the freedom to mobilise and rehabilitate without having to be continually attached to a pump. Occasionally, this method of administration can lead to abdominal bloating, diarrhoea and rarely symptoms analogous to those seen in the dumping syndrome where rapid gastric emptying occurs. Intermittent infusions provide feeds over a longer duration than bolus feeding using an infusion pump. They are anecdotally most commonly used for ease and lifestyle reasons.

Impact on nutritional outcomes

The nutritional benefits derived from gastrostomy feeding are not clearly established. The uncertainties that exist reflect the heterogeneity in populations previously assessed, the paucity of data examining long-term nutritional outcomes and confounders such as the timing of gastrostomy feeding that may have influenced reported outcomes. In addition, the assessment of nutritional status is highly variable. In stroke patients, a frequently cited historical paper showed that gastrostomy feeding was better than nasogastric feeding at improving weight gain and anthropometric measurements at 6 weeks(Reference Norton, Homer-Ward and Donnelly24). This landmark study has helped inform future clinical practice, however it is to be recognised that results were derived from only thirty patients from two UK centres. The more recent and significantly larger, multicentre FOOD trial has enhanced understanding about the timing and method of enteral feeding in stroke patients, however, uncertainty still remains about how gastrostomies impact nutritional status in these individuals(Reference Dennis, Lewis and Warlow26).

The ProGas study provides insights into how gastrostomy feeding influences nutritional outcomes in motor neurone disease(36). In this study the authors report outcomes of 170 patients who had valid weight measurements 3 months post-gastrostomy insertion. Findings showed that in eighty-four (49 %) patients, weight loss was more than 1 kg compared to baseline values. These findings suggest nutritional gains may be limited in this group of patients; however, the timing of gastrostomy insertion may be critical to achieving maximal gains. The uncertainties highlighted here emphasise the need for better studies looking at nutritional outcomes in gastrostomy patients. This would also help improve understanding of the efficacy of this intervention in reducing malnutrition.

Improving patient selection for gastrostomy insertion and aftercare

There has been increasing interest in improving patient selection for gastrostomy insertion(Reference Heaney and Tham46–Reference Nair, Hertan and Pitchumoni48). One method used internationally to optimise referral practice is to employ institutional guidelines that use a standardised referral protocol. Use of a multidisciplinary team in the assessment of patients and dissemination of evidence can allow both caregivers and healthcare professionals to make an informed decision. This approach has been shown (in observational studies) to improve the selection of patients referred for gastrostomy(Reference Sanders, Carter and D'Silva49–Reference Monteleoni and Clark51). These teams have varying composition but usually include a gastroenterologist, a specialist nurse, a dietitian and a speech and language therapist. Although these multidisciplinary teams have been advocated in differing reports from National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death(14) and the British Society of Gastroenterology(Reference Westaby, Young and O'Toole52), it is recognised that many hospitals internationally are still unable to provide this service due to pressures within current healthcare systems(Reference Kurien, Westaby and Romaya53,Reference DeLegge and Kelly54) . This may be a factor influencing the negative sequelae seen associated with PEG insertions.

A ‘cooling off period’ is another approach that is widely adopted and can help improve patient selection. This describes a gap of at least a week between assessment by the nutrition team and the scheduling of the PEG insertion. This practice is based on previously published work by members of our clinical team, and data from the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report, which highlighted that of those individuals that died within 30 d of PEG insertion, 43 % died within the first week(14,Reference Sanders, Carter and D'Silva49) . This 7-d wait policy has two functions. Firstly, it serves to provide an opportunity to reflect on the implications of PEG tube insertion prior to undertaking the procedure (for all those involved in the decision-making process). Secondly, in some cases, patients may succumb during this ‘cooling off’ period, without the difficulty of having to undergo a PEG procedure(Reference Kurien and Sanders55).

When considering whether insertion of a gastrostomy tube is merited, consideration needs to be made to an individuals' quality of life. This consideration must be done in the context of the underlying diagnosis and prognosis, considering moral and ethical issues, as well as respecting the patient's wishes. Guidelines exist to aid clinicians in making decisions on gastrostomy feeding, however the decision to insert a feeding tube should always be made on an individual basis(56,Reference Rabeneck, McCullough and Wray57) . Our recent quality of life work showed that quality of life was seemingly preserved in those undergoing gastrostomy insertion, however, variation occurred dependent upon the indication(Reference Kurien, Andrews and Tattersall58). The relevance of this work could again be in helping inform decision making for both clinicians and patients.

Another factor that may be influencing outcomes following gastrostomy insertion is variations in the organisation of aftercare services. In a UK study looking at the provision of services for gastrostomy, only 64 % of units had a dedicated aftercare service(Reference Kurien, Westaby and Romaya53). The benefits of dedicated home enteral feed teams have been shown to reduce costs and morbidity associated with gastrostomy feeding(Reference Kurien, White and Simpson59,Reference Dinenage, Gower and Van Wyk60) . Given that most complications of gastrostomy feeding occur following hospital discharge, efforts need to be made to improve the delivery of aftercare services for these patients.

Ethical and legal considerations of gastrostomy feeding

Gastrostomy feeding raises ethical and legal issues. Both the Royal College of Physicians and the General Medical Council in the UK have provided guidance on oral feeding and nutrition(61,62) . Artificial feeding is considered a medical treatment in legal terms and requires valid consent prior to commencement. For consent to be valid the person giving consent must have the capacity to do so voluntarily after being given sufficient information to guide informed choice. When a patient has capacity their wish to consent to or refuse treatment should be upheld, even if that decision may lead to death. When a patient lacks capacity, best interests meeting should be held with the multidisciplinary team, those close to that patient or an independent mental capacity advocate. The multidisciplinary team caring for the patient is responsible for giving, withholding or withdrawing treatment, including artificial feeding and hydration and should consider any advance directives, the patient's prognosis and the likely benefits of gastrostomy feeding when making decisions. A limited trial of feeding may sometimes be used but strict criteria regarding what constitutes success should be determined prior to starting gastrostomy feeding(Reference Stroud, Duncan and Nightingale44). Conflicts sometimes arise between healthcare professionals or between the professionals and those close to the patient. In such circumstances, it may be necessary to seek legal advice or seek resolution through a local clinical ethics committee(63). Anecdotally, such conflicts appear to be rising with increased patient and family demands for intervention, which may, in turn, be influenced by emotion or by cultural beliefs.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence dementia guidelines highlight the importance of quality of life in advanced dementia and support the role of palliative care in these individuals from diagnosis until death. Best practice in these patients could be to encourage eating and drinking by mouth for as long as tolerated, utilising good feeding techniques, altering food consistencies and to promote good mouth care. Assisting hand feeding in this way has recently been shown to be of benefit in elderly patients, with volunteer assistance improving oral intake and enjoyment of meals(Reference Gilbert, Appleton and Jerrim64). When disease progression is such that the patient no longer wants to eat or drink, then rather than inserting a gastrostomy tube, end of life care pathways might be considered. Views held by carers and medical staff may prevent progression to end of life care pathways. A questionnaire survey demonstrated that allied healthcare professionals were more likely than physicians to consider gastrostomy feeding when presented with patient scenarios relating to malnutrition(Reference Watts, Cassel and Hickam65).

Conclusion

The provision of gastrostomy feeding remains a contentious issue. Decisions regarding insertions must take into account knowledge of the underlying disease process, prognosis and carefully consider the evidence regarding benefits and burdens. Patients and their caregivers need to be carefully counselled on these issues to help them make an informed choice. If the patient lacks capacity then those involved in the decision making should follow ethical and legal principles to determine the patient's best interests. Future research in gastrostomy feeding should aim to better delineate those who will benefit most from this intervention and when is the optimal timing for PEG insertion.

Financial Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

T. W. and M. K. collectively wrote the manuscript. The article is a summary of an invited presentation to the Joint NS-BSG-BAPEN Winter Conference 2019.