Since ancient times, nutrition has always played an integral part in the pursuit of human health (cf. Hippocrates, Plato, Galen)( Reference Tang and Harris 1 ). Nutrition is central in the prevention of food-related non-communicable diseases representing an important health risk factor and an enormous socio-economic burden for Mediterranean societies. Nevertheless, assessment of food systems and diets sustainability should take into account not only their health benefits but also their environmental impacts. According to the FAO( 2 ): ‘Sustainable Diets are those diets with low environmental impacts which contribute to food and nutrition security and to healthy life for present and future generations…’. The Mediterranean diet (MD) was first presented by Ancel Keys in the 1960s( Reference Keys 3 ). The MD includes lots of olives and olive oil, fruit, vegetables and wholegrain cereals, low-fat dairy, fish, nuts, and legumes but relatively little red meat( Reference Kastorini, Milionis and Esposito 4 ). The MD was inscribed, in November 2010, on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of UNESCO. The nomination was supported by Italy, Spain, Greece and Morocco. Cyprus, Croatia and Portugal joined in 2013. Nevertheless, the MD is a common and shared cultural heritage of all Mediterranean people and countries.

The way food is produced, processed, distributed and consumed determines its environmental impacts or footprints. Environmental impacts refer to the ecological footprint (EF)( Reference Schaefer, Luksch and Steinbach 5 – Reference Ewing, Reed and Galli 8 ), carbon footprint( Reference Wiedmann, Minx and Pertsova 9 ) and water footprint( Reference Mekonnen and Hoekstra 10 , Reference Hoekstra and Chapagain 11 ).

This review paper provides insights about the nutrition–health benefits of the MD and highlights its low environmental footprints, thus making the case for the urgency of its promotion among the Mediterranean population.

Mediterranean food consumption patterns

According to FAO( 12 ), dietary energy in the Mediterranean ranges from 2176 in Palestine to 3694 energy/d per person in Greece. In general, dietary energy is higher in northern Mediterranean countries. The share of plant-based energy in the diet; cereals, vegetable oils (including olive oil), roots and tubers, fruit and pulses, in the Mediterranean is generally higher than 50 %; ranging from 80·7 % in Egypt to 46·6 % in Cyprus. In general, that share is higher than in northern and central Europe and North America (e.g. USA). Generally speaking, it is higher in eastern and southern Mediterranean countries rather than northern ones, while intermediate values are recorded in the Balkans. The largest share of plant-based energy is derived from cereals (from 21·5 % in Spain to 63·7 % in Egypt)( 12 ).

Biodiversity and diversity of plants consumed in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot is the third richest hotspot in the world in terms of its plant biodiversity( Reference Mittermeier, Gil and Hoffmann 13 ). Approximately 30 000 plant species occur, and more than 13 000 species are endemic to the hotspot( Reference Radford, Catullo and de Montmollin 14 ). The Mediterranean Basin Biodiversity Hotspot is a centre of plant endemism, with 10 % of the world's plants( 15 ). About one third of the foodstuff that is used by humankind comes from the Mediterranean climatic region, if not strictly from the topographic basin proper( Reference Harlan 16 ). Barley, wheat, oat, olives, grapes, almonds, figs, dates, peas and other innumerable fruit, vegetables and medicinal or aromatic herbs are derived from wild plants found in the Mediterranean region( Reference Sundseth 17 ).

In the Mediterranean region, a diet has been created over centuries that is unique in its tremendous diversity( Reference Padilla 18 ). Even within the same country, significant dietary differences can be seen. For instance, in Italy, cereals, fruit and vegetables consumption is higher in the southern part of the country( Reference Lupo 19 ). Dietary polymorphism in the Mediterranean region partially reflects religious and cultural differences( Reference Manios, Detopoulou, Visioli, Heinrich, Müller and Galli 20 ). Local foods represent a type of mutual interaction between the availability of locally growing and edible plants, and the nutritional requirements and needs of populations. In general, wild varieties tend to be richer in micronutrients and bioactive secondary metabolites than cultivated ones( Reference Heinrich, Müller and Galli 21 ). Ethnobotanical research has identified about 2300 different plant and fungi taxa that are gathered and consumed in the Mediterranean( Reference Rivera, Obón, Heinrich, Heinrich, Müller and Galli 22 ).

Nutrition and health benefits of the Mediterranean diet

People adhering to the Mediterranean dietary pattern (MDP) comply better with recommended nutrient and micronutrient intakes (Table 1). A wide variety of foods in the MD minimises the possibility of nutrient deficiencies. A higher adherence to the MDP has been associated with a better nutrient profile, i.e. a lower prevalence of individuals showing inadequate intakes of micronutrients in comparison with other patterns such as the Western pattern( Reference Serra-Majem, Bes-Rastrollo and Román-Viñas 23 ). Plant-origin foods represent the core of the MD and provide key nutrients, fibre and protective substances that contribute to general well-being, satiety and the maintenance of a balanced diet( Reference Bach-Faig, Berry and Lairon 24 ).

Table 1. Nutritional benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Percentages (%) of participants who did not comply with recommended nutrient intakes according to quintiles (Q) of adherence to the Mediterranean (MDP) and Western (WDP) dietary patterns calculated through the probabilistic approach

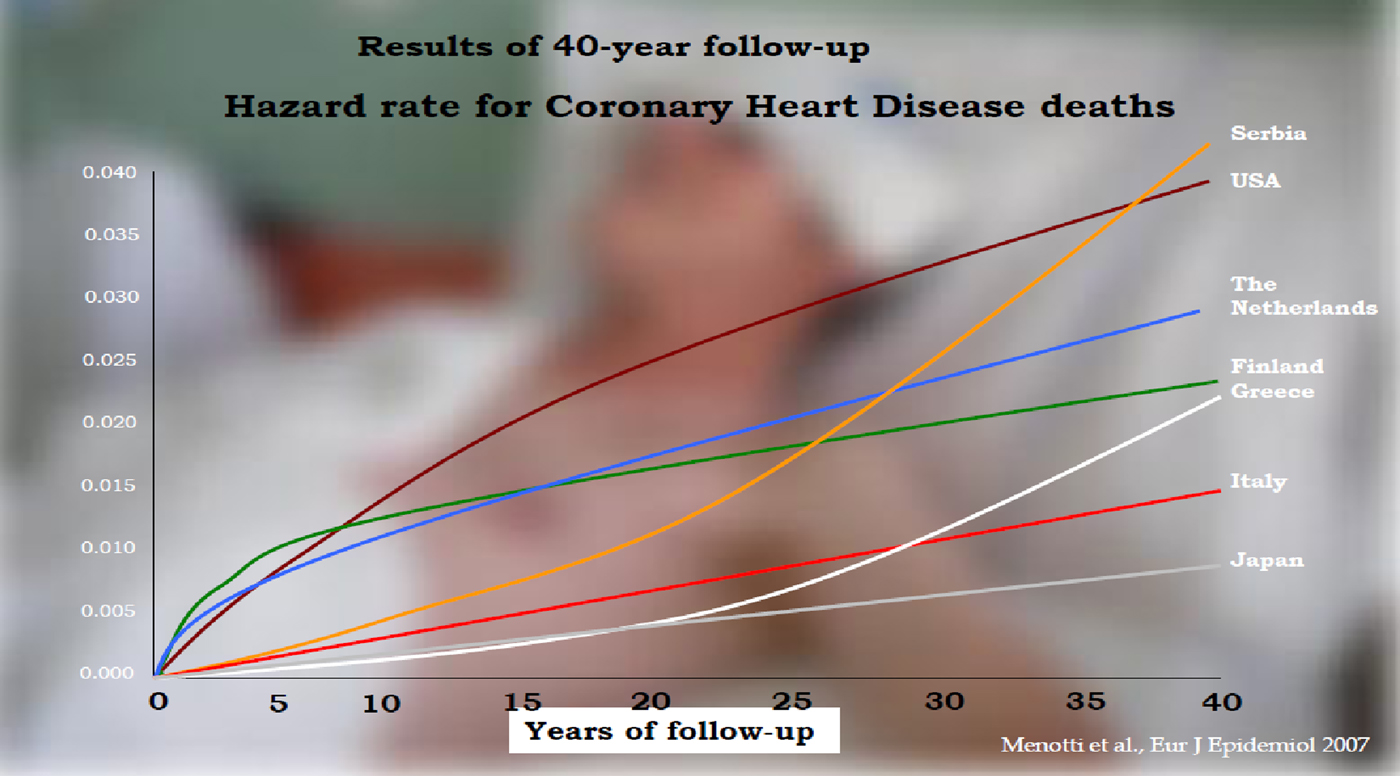

The health benefits of the MD came to public attention with the Seven Countries Study led by Ancel Keys. The first results of the Seven Countries Study( Reference Keys, Menotti and Karvonen 25 ), 12 763 subjects aged 40–59 years in sixteen cohorts of seven countries (USA, Finland, The Netherlands, Italy, former Yugoslavia (Croatia and Serbia), Greece and Japan), were that overall mortality and especially mortality for chronic degenerative diseases was higher among countries consuming a typical Westernised diet, and, by contrast, countries consuming a typical MD had the lowest rates of mortality. Inhabitants of Southern European and North African regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea have a longer life expectancy and lower risk of chronic diseases than in other regions of the world( Reference Ortega 26 ). A meta-analysis of fifty studies, including half a million subjects, has confirmed that eating a MD has a wide variety of health benefits for lifestyle diseases, especially CVD and diabetes( Reference Kastorini, Milionis and Esposito 4 ). The beneficial role of the MD with regard to mortality from all causes, CVD and cancer( Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 27 ), as well as obesity and type 2 diabetes( Reference Giugliano and Esposito 28 , Reference Buckland, Bach and Serra-Majem 29 ) and degenerative diseases has already been reported.

Major biopathophysiological mechanisms include antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of the foods included in the MDP( Reference Giugliano and Esposito 28 , Reference Pitsavos, Panagiotakos and Tzima 30 – Reference Psaltopoulou, Naska and Orfanos 33 ). Foods eaten in the Mediterranean region have many health benefits as they are rich in antioxidants, carotenoids, monounsaturated fats, phytochemicals, etc. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Evolution of hazard rate for CHD in seven countries over a 40-year period. Source: Menotti et al.( Reference Menotti, Lanti and Kromhout 41 ).

A meta-analysis on MD and health status showed that adherence to a MD can significantly decrease: the risk of overall mortality; mortality from CVD; incidence of or mortality from cancer and incidence of chronic neurogenerative diseases (i.e. Parkinson and Alzheimer)( Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate 27 ).

Olives and olive oil are a key component in the MD and a key contributor to the healthy aspects attributed to it( Reference Serra-Majem, Ngo de la Cruz and Ribas 34 ). The benefits of olive oil are attributed primarily to the high level of oleic acid as well as the powerful phenolic antioxidants, which are specific to olives alone. The antioxidants and polyphenols from olive oil, in addition to vitamin E and vitamin C, have been shown to decrease incidences of disease including CHD and cancer. Virgin olive oil has a greater concentration of phenols and is a source of thirty phenolic compounds( Reference Fidanza 35 ). Olive oil is a crucial element of the MD, not only for its inherent nutritional effects but also the cumulative benefits of the foods that are typically prepared with olive oil (e.g. vegetables, fish)( Reference Serra-Majem, Ngo de la Cruz and Ribas 34 ).

Environmental footprints of Mediterranean food consumption patterns

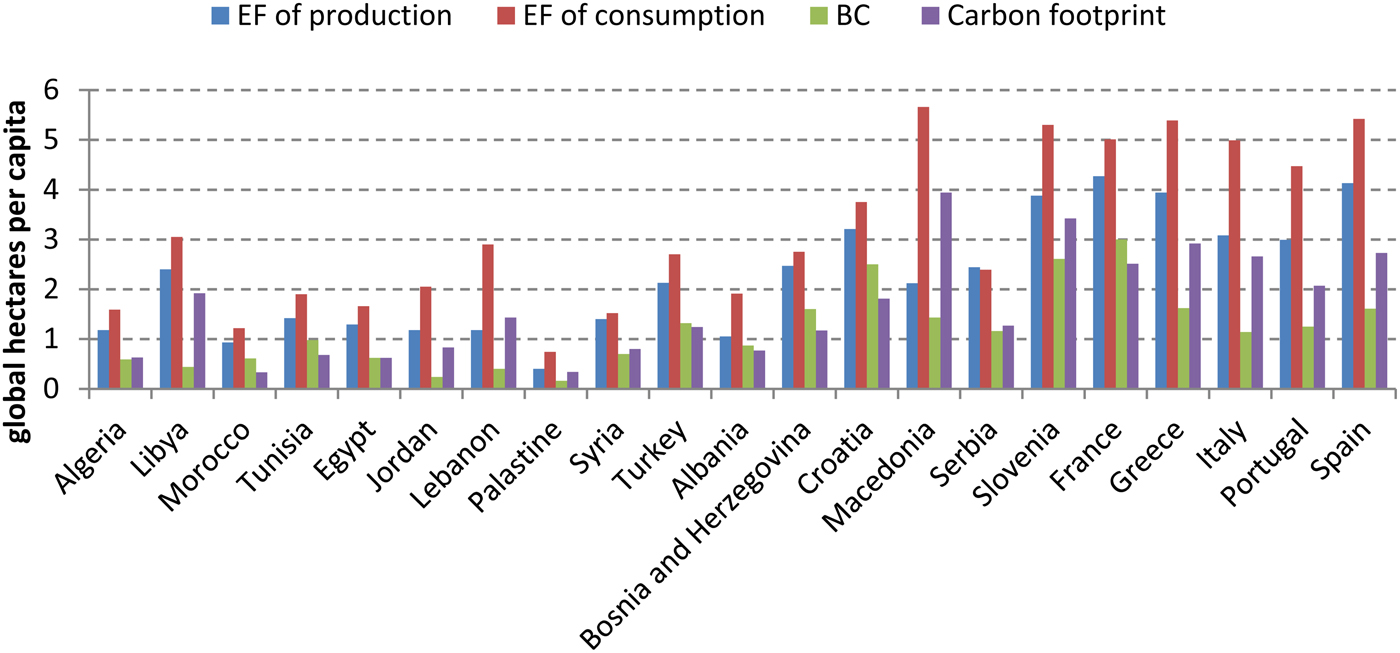

The Mediterranean EF of consumption is always higher than the EF of production, except for Serbia. The carbon footprint alone is generally higher than the biocapacity( Reference Ewing, Moore and Goldfinger 7 ) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Ecological footprint (EF) of production, EF of consumption, biocapacity (BC) and carbon footprint (CF) in the Mediterranean region. Source: Adapted from Ewing et al.( Reference Ewing, Moore and Goldfinger 7 ).

In general, the northern Mediterranean countries have a higher EF with respect to North Africa and Middle East ones. EF of production and consumption as well as carbon footprint of North American countries are higher than in Mediterranean countries, even northern ones. The cropland EF is the highest in Mediterranean countries. In general, the EF per capita in the Mediterranean increased in the period 1961–2007, while the biocapacity decreased, thus the ecological deficit increased. On average, the EF has increased by 47·4 %, while the biocapacity decreased by 36·4 %. The Mediterranean countries have a net demand on the planet: on average, 2 years and 3 months are needed to regenerate the resources used for production, while 3 years and 4 months are needed to regenerate the resources effectively consumed( Reference Ewing, Moore and Goldfinger 7 ).

Red meat is the food with greatest ecological impact, while fruit and vegetables have a decidedly limited impact( 36 ). In general, lower is the animal food consumption and also lower is the environmental impact. The livestock sector is an important driver of deforestation, land degradation, pollution, climate change, erosion, etc.( Reference Steinfeld, Gerber and Wassenaar 37 ).

In the Mediterranean, water resources are limited and unevenly distributed. Food supply directly translates into consumptive water use. Water requirements for plant and animal products vary widely( Reference Falkenmark and Rockström 38 ). Countries of the north Mediterranean have higher water footprint of consumption per year and per capita (2279 m3) compared with North Africa (1892 m3), Balkans (1708 m3) and Middle East (1656 m3). Most of the water footprint of consumption is due to agricultural products consumption (average is about 91 % of the total water footprint of consumption): 96 % in North Africa, 93 % in Middle East, 82 % in Balkans and 91 % in northern Mediterranean. Net virtual water flow between 1995 and 2005 in the Mediterranean is positive except in Tunisia, Syria and Serbia( Reference Mekonnen and Hoekstra 10 ).

The Mediterranean diet: beyond health and environmental benefits

The food pyramid that reflects MDP has been associated with good health( Reference Willett, Sacks and Trichopoulou 39 ) but also respects the environment. Reclassifying foods on the basis of their negative effect on the environment produces an environmental pyramid. When the environmental pyramid is brought alongside the food pyramid, it creates a food–environmental pyramid called the double pyramid. It shows that those foods with higher recommended consumption levels in the MD are also those with lower environmental impact( Reference Steinfeld, Gerber and Wassenaar 37 ). Dernini et al. ( Reference Dernini, Berry and Serra-Majem 40 ) presented recently the Med Diet 4.0 framework (Fig. 3) in which the well-documented health and nutrition advantages of the MD are incorporated with three additional sustainable benefits: low environmental impacts and rich in biodiversity, high socio-cultural food values and positive economic return locally.

Fig. 3. Med Diet 4.0 framework showing the four benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Source: Dernini et al.( Reference Dernini, Berry and Serra-Majem 40 ).

Conclusions

The traditional MD offers considerable nutrition and health benefits, especially in the prevention of major chronic diseases. It has also lower environmental impacts (ecological, carbon and water footprints) than northern Europe and American diets. In fact, by using less meat and animal products, MD reduce health impacts of meat consumption and environmental impacts of livestock sector on biodiversity and natural resources (e.g. water, land). Therefore, adopting the MDP means reconciling personal well-being (personal ecology) with the environment (ecological context). However, there is an ecological deficit in the Mediterranean since the EF of consumption is higher than the biocapacity. Furthermore, population increase, especially in the southern and eastern Mediterranean countries, will increase pressure on the limited and scarce Mediterranean natural resources in particular water. Therefore, actions and measures aiming at MD safeguarding and sustainability should be promoted. Moreover, the MDP should be promoted as a cornerstone in public health strategies and sustainable diets should become central in sustainable development policies.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our collaborators from CIHEAM-Bari for their input and English editing.

Financial Support

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authorship

Y. A. and H. E. provided the drafts. R. C. has enriched and reviewed the paper.