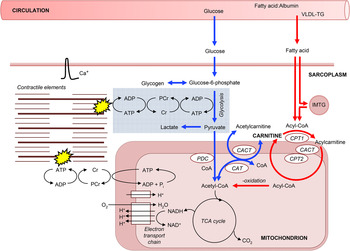

Carbohydrate and fat are the primary fuel sources for mitochondrial ATP resynthesis in human skeletal muscle. The relative utilisation of these two substrates during exercise can vary substantially and depends strongly on substrate availability and exercise duration and intensity. Fat constitutes the largest energy reserve in the body, and in terms of the amount available, it is not limiting to endurance exercise performance. However, fat exhibits a relatively low maximal rate of oxidation in vivo, which begins to measurably decline at an exercise intensity of approximately 60–70 % of maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), above which muscle glycogen becomes the major fuel supporting ATP resynthesis( Reference Romijn, Coyle and Sidossis 1 – Reference Achten, Gleeson and Jeukendrup 3 ). The muscle glycogen stores are limited and it has been well established that muscle glycogen depletion coincides with fatigue during very prolonged high-intensity endurance exercise( Reference Bergstrom, Hermansen and Hultman 4 ). As fatigue can be postponed by increasing pre-exercise muscle glycogen content( Reference Bergstrom, Hermansen and Hultman 4 ), it is thought that augmenting the rate of fat oxidation during endurance exercise could delay glycogen depletion and improve prolonged endurance exercise performance. Indeed, it has long been known that enhanced fat oxidation is one of the main muscle adaptations to endurance exercise training( Reference Johnson, Walton and Krebs 5 ). However, the mechanisms that regulate the relative contributions of carbohydrate and fat oxidation in skeletal muscle during exercise have not been clearly elucidated. Several potential regulatory points (Fig. 1) could influence the decline in the rate of fat oxidation in skeletal muscle during high-intensity endurance exercise, including: (1) regulation of lipolysis within adipose tissue and intramuscular TAG pools; (2) transport and delivery of circulating NEFA from adipose tissue stores to working skeletal muscle; (3) transport of fatty acids across the muscle cell membrane and within the cell cytosol to the outer mitochondrial membrane; (4) transport of fatty acid across the outer mitochondrial membrane via carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), the rate-limiting step in fatty acid oxidation; (5) intramitochondrial enzymatic reactions distal to CPT1. The present review will primarily address the theory that a carbohydrate flux-mediated reduction in the availability of muscle carnitine, the major substrate for CPT1, is a key mechanism for the decline in fat oxidation during high-intensity exercise. This is discussed in relation to recent work in this area taking advantage of the discovery that the skeletal muscle carnitine content can be nutritionally increased in vivo in human subjects and has a significant impact upon fuel selection during endurance exercise.

Fig. 1. A schematic diagram of the roles of carnitine within the context of skeletal muscle fuel metabolism for ATP resynthesis during exercise. Carnitine's role in long-chain fatty acid (acyl group) translocation into the mitochondrial matrix, for subsequent β-oxidation is highlighted in red, whereas the role of carnitine as a buffer of excess acetyl-CoA production and as a stockpile of acetyl groups is highlighted in blue. PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; CAT, carnitine acetyltransferase; CACT, carnitine acylcarnitine translocase; CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; IMTG, intramuscular tryglyceride; Cr, creatine; PCr, phosphocreatine.

Integration of fat and carbohydrate oxidation during exercise

There is increasing evidence to suggest that fat oxidation during exercise is directly regulated by the rate of flux through the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme complex (PDC), a rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle carbohydrate oxidation. Increasing exercise intensity, from moderate to high, or increasing carbohydrate availability during exercise, increases glycolysis and flux through the PDC with a corresponding decrease in the rate of fat oxidation( Reference Romijn, Coyle and Sidossis 1 , Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu 2 , Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 ). A likely site of the regulation of fat oxidation by carbohydrate flux is CPT1. Increasing glucose availability at rest, via a hyperglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp, decreases long-chain fatty acid ([13C]oleate) oxidation with no effect on medium-chain fatty acid ([13C]octanoate) oxidation( Reference Sidossis and Wolfe 7 ). This would suggest an inhibition of fat oxidation at the level of CPT1 as medium-chain fatty acids cross the mitochondrial membrane to be oxidised independently of CPT1. The same effect of carbohydrate was seen during moderate-intensity exercise at 50 % VO2max, where hyperglycaemia (induced as a result of pre-exercise ingestion of glucose) increased glycolytic flux and reduced long-chain fatty acid ([1-13C]palmitate) oxidation( Reference Coyle, Jeukendrup and Wagenmakers 8 ). Again, medium-chain [1-13C]octanoate oxidation was unaffected, suggesting that carbohydrate metabolism can also directly limit fat oxidation at the level of CPT1 during exercise. It should be noted that these responses might have been mediated, at least in part, via an insulin-induced inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis, resulting in decreased plasma NEFA availability. However, in the study of Sidossis and Wolfe( Reference Sidossis and Wolfe 7 ), normal plasma NEFA was maintained constant and muscle long-chain acyl-CoA levels did not change, suggesting that NEFA availability, uptake and cytosolic transport were not limiting. Furthermore, restoring plasma NEFA concentration during the exercise trial, via lipid and heparin infusion, did not fully restore fat oxidation rates, again suggesting that the inhibitory effect of increased carbohydrate availability resides at the level of oxidation, rather than NEFA availability( Reference Romijn, Coyle and Sidossis 9 ). In support of this theory, increasing fat oxidation rates 2-fold during exercise at 65 % VO2max, due to different pre-exercise muscle glycogen content, has no effect on muscle NEFA uptake rates or FAT/CD36 (the protein responsible for NEFA uptake into skeletal muscle) protein levels( Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 ).

A glance at carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 regulation during exercise

Several intracellular mechanisms leading to the down-regulation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation at the level of CPT1 during exercise with high glycolytic flux have been proposed, including inhibition of CPT1 by malonyl-CoA, acylcarnitine or acidosis, and reduced substrate availability of carnitine or long-chain fatty acyl-CoA. The following section will focus on mechanisms that have been investigated in vivo and in human subjects.

Malonyl-CoA is a potent inhibitor of CPT1 activity in vitro and is a likely candidate as the intracellular regulator of the rate of long-chain fatty acid oxidation human skeletal muscle. Indeed, in resting human skeletal muscle, changes in malonyl-CoA concentration have occurred with opposite changes in fat oxidation( Reference Bavenholm, Pigon and Saha 10 , Reference Rasmussen, Holmback and Volpi 11 ). Skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA concentration is regulated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and by the cytosolic concentration of citrate, which inactivate and activate the enzyme responsible for malonyl-CoA synthesis from acetyl-CoA (acetyl-CoA carboxylase), respectively( Reference Saha, Kurowski and Ruderman 12 ). Thus, increased muscle concentrations of acetyl-CoA and citrate, due to increased glycolytic flux, would increase muscle malonyl-CoA concentration (via an increase in acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity) and, therefore, inhibit long-chain fatty acid oxidation via CPT1. In support of this theory, a significant negative correlation was obtained between muscle malonyl-CoA content and fat oxidation rates in healthy middle-aged men during a two-step euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp( Reference Bavenholm, Pigon and Saha 10 ). Furthermore, hyperglycaemia with hyperinsulinaemia increased resting skeletal muscle malonyl-CoA content 3-fold in healthy human subjects, resulting in a functional decrease in CPT1 activity, as evidenced by an 80 % inhibition of leg [13C]oleate oxidation, with no change in [13C]octanoate oxidation( Reference Rasmussen, Holmback and Volpi 11 ). However, it appears that muscle malonyl-CoA concentration may not regulate long-chain fatty acid oxidation during exercise. Roepstorff et al. ( Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 ) demonstrated that, despite a 122 % increase in fat oxidation rates (due to depleted pre-exercise muscle glycogen content) during exercise at 65 % VO2max, there were no differences in muscle malonyl-CoA content compared to control. These findings are also supported by other human exercise studies where no association between malonyl-CoA content and fat oxidation rates were obtained in skeletal muscle during prolonged moderate-intensity exercise( Reference Odland, Heigenhauser and Lopaschuk 13 ) or during graded-intensity exercise( Reference Odland, Heigenhauser and Wong 14 , Reference Dean, Daugaard and Young 15 ). Furthermore, α2-AMPK activity more than doubled with an associated 6-fold increase in acetyl-CoA carboxylase-β (muscle isoform) phosphorylation, and significant decrease in malonyl-CoA concentration was observed following both prolonged and high-intensity exercise, where fat oxidation paradoxically increased and decreased, respectively( Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 , Reference Dean, Daugaard and Young 15 ). Taken together, these findings would suggest that malonyl-CoA does not play a major role in the regulation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation in human skeletal muscle during exercise.

Carnitine is the principal substrate for CPT1, suggesting that it may play a role in the regulation of fat oxidation. Irving Fritz and co-workers first established that mitochondria in a variety of tissues are impermeable to fatty acyl-CoA, but not to fatty acylcarnitine, and that carnitine and CPT1 are essential for the translocation of long-chain fatty acids into skeletal muscle mitochondria for β-oxidation( Reference Fritz and Marquis 16 ). Since these discoveries, it has been established that CPT1, situated within the outer mitochondrial membrane, catalyses the reversible esterification of carnitine with long-chain acyl-CoA to form long-chain acylcarnitine. Cytosolic acylcarnitine is then transported into the mitochondrial matrix in a simultaneous 1 : 1 exchange with intramitochondrial-free carnitine via the carnitine acylcarnitine translocase, which is situated within the mitochondrial inner membrane (Fig. 1). Once inside the mitochondrial matrix, acylcarnitine is transesterified back to free carnitine and long-chain acyl-CoA in a reaction catalysed by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2, which is situated on the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The intramitochondrial long-chain acyl-CoA is then oxidised and cleaved by the β-oxidation pathway( Reference McGarry and Brown 17 ). The significance of this ‘carnitine cycle’ to fat oxidation during exercise is highlighted in patients with carnitine, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 or carnitine acylcarnitine translocase deficiency (CPT1 deficiency appears to be incompatible with life) who typically experience severely reduced rates of fat oxidation during prolonged exercise along with muscle pain and weakness, hypoglycaemia and hypoketosis. CPT1 is considered to be the rate-limiting enzyme for long-chain fatty acid entry into the mitochondria and oxidation, but carnitine is classically not thought to be rate limiting to CPT1. Indeed, the concentration of carnitine in skeletal muscle is approximately 5 mm intracellular water( Reference Cederblad, Lindstedt and Lundholm 18 ) and far in excess of the in vitro Michaelis–Menten constant (K m) of muscle CPT1 for carnitine of approximately 0·5 mm ( Reference McGarry, Mills and Long 19 ). However, the enzymes of the carnitine cycle co-immunoprecipitate and are mainly located in the specialised contact sites between outer and inner mitochondrial membranes in order to allow metabolic channelling( Reference Fraser and Zammit 20 ). Thus, it is likely that the intramitochondrial content of free carnitine determines carnitine availability to CPT1 and, as this is approximately 10 % of the whole muscle carnitine pool( Reference Idell-Wenger, Grotyohann and Neely 21 ), that in vivo carnitine availability could be rate limiting to the CPT1 reaction. Indeed, during conditions of high glycolytic flux, such as during exercise at a high intensity or with elevated carbohydrate availability, muscle-free carnitine availability is reduced( Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu 2 , Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 ).

Free carnitine availability is reduced during high-intensity exercise

The reduction in free carnitine availability observed with high glycolytic flux first became apparent in 1966 when Childress and Sacktor recognised that the blowfly flight muscle, which does not oxidise fatty acids during flight, was rich in carnitine and carnitine acetyltransferase (CAT)( Reference Childress and Sacktor 22 ). During the initial phase of flight, acetyl-CoA from glycolysis was generated faster than its utilisation by the TCA cycle, with a corresponding 4-fold increase in acetylcarnitine. Childress and Sacktor suggested that carnitine accepted the excess acetyl groups, via the action of mitochondrial CAT, in order to maintain a viable pool of free CoA to permit the continuation of pyruvate oxidation (Fig. 1). Subsequent work from Harris and co-workers in human subjects and thoroughbred horses demonstrated that following a few minutes of intense, near-maximal exercise, muscle-free carnitine content was reduced from approximately 80 % of the total muscle carnitine pool at rest (muscle total carnitine content is approximately 20 mm/(kg dry muscle (dm)) in human subjects) to approximately 20 %, with almost all of the reduction being attributed to formation of acetylcarnitine( Reference Foster and Harris 23 – Reference Carlin, Harris and Cederblad 25 ). However, there was no change in muscle acetylcarnitine content following a few minutes of exercise at lower intensities( Reference Sahlin 26 , Reference Constantin-Teodosiu, Carlin and Cederblad 27 ). Constantin-Teodosiu and co-workers( Reference Constantin-Teodosiu, Cederblad and Hultman 28 ) also demonstrated a rapid increase in acetylcarnitine formation in human subjects from 3 to 13 mm/(kg dm) following 3 min intense exercise at 75 % VO2max. Furthermore, over the next hour of exercise, acetylcarnitine gradually increased to 16 mm/(kg dm), suggesting that exercise duration, as well as intensity, contributes to acetylcarnitine accumulation, albeit to a lesser degree. If a second bout of exercise is performed( Reference Campbell-O'Sullivan, Constantin-Teodosiu and Peirce 29 ), or if exercise is continued for several hours( Reference Watt, Heigenhauser and Dyck 30 ), then acetyl-CoA availability may actually be less than the demands of the TCA cycle and the stockpiled acetyl groups can be used as a fuel source via the reverse CAT reaction (Fig. 1). Indeed, Seiler et al. ( Reference Seiler, Koves and Gooding 31 ) recently observed an inability to use stockpiled acetylcarnitine following exercise in an incomplete CAT knockout mouse, i.e. the incomplete reverse CAT reaction resulted in a decline in acetyl-CoA. However, this did not warrant their conclusion ‘this observation is consistent with the premise that during intense exercise CAT catalyses net flux in the direction of acetyl-CoA’, which is certainly not consistent with the aforementioned studies in human subjects that observed a net accumulation of acetylcarnitine during intense exercise.

Research by van Loon et al. ( Reference van Loon, Greenhaff and Constantin-Teodosiu 2 ) demonstrated that a 35 % decrease in the rate of long-chain fatty oxidation that occurred at an exercise intensity above 70 % VO2max, measured using a [U-13C]palmitate tracer, was paralleled by a 65 % decrease in skeletal muscle-free carnitine content. In support of these findings, Roepstorff et al. ( Reference Roepstorff, Halberg and Hillig 6 ) demonstrated a 2·5-fold decrease in the rate of fat oxidation, compared to control, during moderate-intensity exercise (65 % VO2max) when free carnitine availability was reduced to 50 % (12 mm/(kg dm)) of the total carnitine store, as a result of pyruvate, and thereby acetyl-CoA, production being increased due to elevated pre-exercise muscle glycogen stores. During bicycle exercise at 75 % VO2max to exhaustion, both muscle-free carnitine content and fat oxidation rates were also markedly higher with low pre-exercise muscle glycogen content compared to control( Reference Putman, Spriet and Hultman 32 ). Taken together, the aforementioned studies suggest a relationship between skeletal muscle-free carnitine availability (and therefore carbohydrate metabolism) and the regulation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation rates, via CPT1, in human skeletal muscle during exercise.

Is reduced free carnitine availability related to insulin resistance?

It would be remiss not to mention a recent growing body of research in the area of skeletal muscle carnitine metabolism, particularly related to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is characterised by a ‘metabolic inflexibility’ in the reciprocal relationship between fatty acid and glucose oxidation within skeletal muscle( Reference Kelley and Mandarino 33 ). In keeping with observation in the same incomplete CAT knockout model by Muoio et al. ( Reference Muoio, Noland and Kovalik 34 ), a recent article of Lindeboom et al. ( Reference Lindeboom, Nabuurs and Hoeks 35 ) asserts that ‘the transformation of excessive acetyl-CoA into acetylcarnitine is important to maintain metabolic flexibility’, and that ‘compromised capacity to generate acetylcarnitine, either due to reduced CAT activity or low carnitine concentration, may reduce pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, hence reducing oxidative degradation of glucose’. Contrary to this opinion, biochemically determined human muscle acetylcarnitine content is reduced under insulin-stimulated, high-glucose conditions( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Laithwaite 36 ), and increased in the insulin resistant state( Reference Constantin-Teodosiu, Constantin and Stephens 37 , Reference Tsintzas, Chokkalingam and Jewell 38 ). What is more, as aforementioned, compelling evidence has demonstrated a positive, constant linear relationship exists between muscle acetyl-CoA formation and acetylcarnitine accumulation over low-to-maximum rates of mitochondrial flux( Reference Childress and Sacktor 22 , Reference Harris, Foster and Hultman 24 , Reference Constantin-Teodosiu, Carlin and Cederblad 27 , Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Greenhaff 39 ). Lindeboom et al. ( Reference Lindeboom, Nabuurs and Hoeks 35 ) themselves report maximal ex vivo CAT activity in participants with type 2 diabetes of 52·6 nmol/mg protein per min, which is far in excess of PDC flux rates even during high-intensity exercise (15 nmol/mg protein per min)( Reference Constantin-Teodosiu, Carlin and Cederblad 27 ). This clearly demonstrates that CAT is not limiting the equilibrium between acetyl-CoA and acetylcarnitine, making it highly unlikely that acetylcarnitine accumulation could be compromised for reasons other than rates of acetyl-CoA formation from pyruvate dehydrogenase or β-oxidation reactions. Illustrated another way, if CAT activity was indeed limiting in insulin-resistant individuals, then mitochondrial ATP production would be markedly suppressed, as the rapid sequestering of the micromolar concentrations of mitochondrial-free CoA as acetyl-CoA would immediately compromise pyruvate dehydrogenase and TCA cycle flux. This clearly does not happen, rather it is likely that group differences in ex vivo maximal CAT activity and in vivo mitochondrial function reported by Lindeboom et al. ( Reference Lindeboom, Nabuurs and Hoeks 35 ) would be dissipated if corrected for mitochondrial content, particularly given the apparent impairment of muscle mitochondrial function in patients with type 2 diabetes is accounted for by differences in mitochondrial content( Reference Boushel, Gnaiger and Schjerling 40 ). Finally, the resting muscle acetylcarnitine content of participants with type 2 diabetes in Lindeboom et al. was 12 % of the measured total carnitine pool, suggesting that free carnitine was 88 % of the total muscle carnitine pool and making it highly improbable that free carnitine availability was limiting to pyruvate dehydrogenase flux and acetylcarnitine formation.

Can skeletal muscle carnitine content be increased?

Further insight into whether free carnitine availability is limiting to CPT1 and the rate of fatty acid oxidation can be provided by increasing skeletal muscle carnitine content. However, the majority of the pertinent studies in healthy human subjects to date have failed to increase skeletal muscle carnitine content via oral or intravenous l-carnitine administration( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Greenhaff 39 ). For example, neither feeding l-carnitine daily for up to 3 months( Reference Wächter, Vogt and Kreis 41 ), nor intravenously infusing l-carnitine for up to 5 h( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Laithwaite 42 ), had an effect on muscle total carnitine content, or indeed net uptake of carnitine across the leg( Reference Soop, Bjorkman and Cederblad 43 ) or arm( Reference Shannon, Nixon and Greenhaff 44 ) (Table 1). Furthermore, feeding 2–5 g/d l-carnitine for 1 week to 3 months prior to a bout of exercise had no effect on perceived exertion, exercise performance, VO2max or markers of muscle substrate metabolism such as RER, VO2, blood lactate, leg NEFA turnover and post-exercise muscle glycogen content( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Greenhaff 39 ). What was apparent from the earlier carnitine supplementation studies was that muscle carnitine content was either not measured or, if it was, not increased. This is likely explained by the finding that carnitine is transported into skeletal muscle against a considerable concentration gradient (>100-fold) that is tightly regulated and saturated under normal conditions, and so it is unlikely that simply increasing plasma carnitine availability per se will increase muscle carnitine transport and storage( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Greenhaff 39 ). Indeed, recent human and porcine studies of arterio-venous carnitine fluxes confirmed that net muscle carnitine uptake/efflux is negligible under fasting conditions( Reference Shannon, Nixon and Greenhaff 44 , Reference Schooneman, Ten Have and Van Vlies 45 ), with systemic concentrations of carnitine and acylcarnitines largely governed by gut absorption, hepatic release and renal filtration( Reference Schooneman, Ten Have and Van Vlies 45 ). However, insulin appears to stimulate skeletal muscle carnitine transport, and intravenously infusing l-carnitine in the presence of high circulating insulin (>50 mU/l) can increase muscle carnitine content by 15 %( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Laithwaite 36 , Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Laithwaite 42 , Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Laithwaite 46 ). Furthermore, ingesting relatively large quantities of carbohydrate in a beverage (>80 g) can stimulate insulin release to a sufficient degree to increase whole body carnitine retention when combined with 3 g carnitine feeding and, if continued for up to 6 months (80 g carbohydrate + 1·36 g l-carnitine twice daily) can increase the muscle store by 20 % compared to carbohydrate feeding alone( Reference Wall, Stephens and Constantin-Teodosiu 47 ). Indeed, ingesting 80 g carbohydrate facilitated a positive net arterio-venous carnitine balance across the forearm( Reference Shannon, Nixon and Greenhaff 44 ), which, assuming the majority of the measured plasma carnitine extraction across the forearm occurred into skeletal muscle, equated to a whole body muscle accumulation of 390 µm and aligned well with the 370 µm (60 mg) carnitine retention predicted from differences in urinary carnitine excretion in previous studies( Reference Stephens, Evans and Constantin-Teodosiu 48 ). Extended to a chronic feeding scenario, this would equate to a daily increase in muscle carnitine content of 50 µm/(kg dm), which would augment muscle total carnitine content stores (approximately 20 mm/(kg dm)) by 22 % over 12 weeks. Again, this extrapolation is in good agreement with the 21 % increase in muscle carnitine content reported by Stephens et al. ( Reference Stephens, Wall and Marimuthu 49 ). However, such a large carbohydrate load per se (160 g/d) will likely affect metabolism and alter body composition( Reference Stephens, Wall and Marimuthu 49 ) and so investigation into alternative oral insulinogenic formulations that can stimulate muscle carnitine accumulation using lower carbohydrate loads is warranted. For example, whey protein has previously been fed with carbohydrate to promote insulin-mediated muscle creatine retention( Reference Steenge, Simpson and Greenhaff 50 ) and, unlike carbohydrate, prolonged protein supplementation is less likely to influence body fat content( Reference Cermak, Res and de Groot 51 ). Unpublished data from our laboratory would suggest that daily feeding of 3 g l-carnitine in combination with a beverage containing 44 g carbohydrate and 13 g protein results in about a 20 % increase in the muscle carnitine pool over 24 weeks (Chee et al., unpublished results).

Table 1. A summary of studies that have measured muscle carnitine content or balance following l-carnitine administration

HIIT, high-intensity interval training; PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme complex.

Does increasing muscle carnitine content reduce the inhibition of fat oxidation during high-intensity exercise?

Consistent with the hypothesis that free carnitine availability is limiting to CPT1 flux and fat oxidation, the increase in muscle total carnitine content in the study of Wall et al. ( Reference Wall, Stephens and Constantin-Teodosiu 47 ) equated to an 80 % increase in free carnitine availability during 30 min exercise at 50 % VO2max compared to control and resulted in a 55 % reduction in muscle glycogen utilisation. Furthermore, this was accompanied by a 30 % reduction in PDC activation status during exercise, suggesting that a carnitine-mediated increase in fat-derived acetyl-CoA inhibited PDC and muscle carbohydrate oxidation. Put another way, l-carnitine supplementation increased muscle-free carnitine concentration during exercise at 50 % VO2max from 4·4 to 5·9 mm/l intracellular water, equating to an intramitochondrial concentration of 0·44 and 0·59 mm/l, which is below and above the K m of CPT1 for carnitine, respectively( Reference McGarry, Mills and Long 19 ). However, during 30 min exercise at 80 % VO2max with increased muscle total carnitine content, the same apparent effects on fat oxidation were not observed( Reference Wall, Stephens and Constantin-Teodosiu 47 ). In contrast, there was greater PDC activation (40 %) and flux (16 % greater acetylcarnitine), resulting in markedly reduced muscle lactate accumulation in the face of similar rates of glycogenolysis compared to control. This suggested that free carnitine availability was limiting to PDC flux during high-intensity exercise and that increasing muscle carnitine content resulted in a greater acetyl-CoA buffering capacity and better matching of glycolytic to PDC flux. The study by Wall et al. ( Reference Wall, Stephens and Constantin-Teodosiu 47 ) also demonstrated a remarkable improvement in exercise performance in all participants (11 % mean increase) during a 30-min cycle ergometer time trial in the carnitine-loaded state. This is consistent with animal studies reporting a delay in fatigue development by 25 % during electrical stimulation in rat soleus muscle strips incubated in carnitine in vitro ( Reference Brass, Scarrow and Ruff 52 ). Whether these improvements in endurance performance are due to glycogen sparing as a result of a carnitine-mediated increase in fat oxidation, or the reduced reliance on non-oxidative ATP production from carbohydrate oxidation (increase acetyl-group buffering and reduced lactate accumulation) requires further investigation, but due to the high-intensity nature of the time trial, the latter would appear more likely. Nevertheless, the long-held belief that carnitine supplementation can improve endurance performance via augmenting its role in fat oxidation should be revised to place more emphasis on the major role that carnitine plays in carbohydrate metabolism during exercise.

Does increasing muscle carnitine content affect muscle metabolism during very high-intensity exercise?

During very high-intensity exercise (>100 % VO2max), where there is a negligible contribution of fat oxidation to energy expenditure, there is a plateau in muscle acetyl-group accumulation that is associated with a greatly accelerated rate of lactate production( Reference Stephens, Constantin-Teodosiu and Greenhaff 39 , Reference Harris and Foster 53 ). This increasing proportion of glycolytic flux that is directed towards lactate formation is often cited as a key component in the development of fatigue during very intense exercise( Reference Gladden 54 ). Under these conditions, it is unclear whether free carnitine availability is limiting to PDC flux and mitochondrial ATP resynthesis, or simply that TCA cycle flux and PDC flux (i.e. mitochondrial capacity) are maximal. This is most evident during repeated bouts of very high-intensity exercise, where acetylcarnitine accumulation during the first bout of exercise prevents further acetyl-group buffering during subsequent bouts due to reduced free carnitine availability, which results in an increased reliance on phosphocreatine degradation (indicative of a declining contribution from mitochondrial ATP delivery) and ultimately fatigue( Reference Shannon, Ghasemi and Greenhaff 55 ). Thus, if carnitine availability is indeed limiting to PDC flux during intense, repeated-bout exercise, it is plausible that increasing skeletal muscle carnitine availability as in( Reference Wall, Stephens and Constantin-Teodosiu 47 ) during a prolonged period of high-intensity interval (i.e. repeated bout) training (HIIT) could influence the adaptations to this type of training. However, we have recently demonstrated that although increasing skeletal muscle-free carnitine content via 24 weeks of twice daily l-carnitine (1·36 g) and carbohydrate (80 g) feeding increased the capacity to buffer excess acetyl groups during a single 3 min bout of high-intensity exercise at 100 % VO2max (as evidenced by a reduced muscle phosphocreatine degradation), it did not further influence skeletal muscle metabolism during a repeated bout, nor improve training-induced changes in muscle metabolism, VO2max, or work output over 24 weeks of HIIT( Reference Shannon, Ghasemi and Greenhaff 55 ). This would suggest that either acetylcarnitine formation, or PDC flux, is not limiting to mitochondrial ATP delivery during repeated bouts of exercise of this duration and intensity, or that the adaptations to HIIT outweighed any benefit of increasing free carnitine availability. Indeed, following 24 weeks of HIIT non-mitochondrial ATP production and acetylcarnitine accumulation during a second bout of exercise were blunted to such an extent that they were lower than the pre-training first bout, suggesting a better matching of PDC and TCA cycle flux during repeated bouts of exercise and a lower dependence on mitochondrial acetyl-group buffering.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it appears that skeletal muscle carnitine availability influences fuel selection during exercise. Carnitine availability appears limiting to the CPT1 reaction, such that during high-intensity exercise, a carbohydrate flux-mediated decline in free carnitine is paralleled by a decline in the rate of fat oxidation. Indeed, nutritionally increasing skeletal muscle carnitine content increases fat oxidation during low-intensity exercise. However, increasing carnitine availability during high-intensity exercise does not offset the decline in fat oxidation, but facilitates a better matching of carbohydrate flux by buffering excess acetyl groups from the PDC reaction. Thus, the long-held belief that carnitine supplementation can improve endurance performance via augmenting its role in fat oxidation, should be revised to place more emphasis on the major role that carnitine plays in carbohydrate metabolism during exercise, particularly as increasing muscle carnitine content can improve high-intensity exercise performance and most athletes compete at high exercise intensities. However, caution should be taken as nutritionally increasing carnitine content appears to have little effect during repeated bouts of exercise at very high intensities or adaptation to HIIT training, likely because oxidative metabolism is already maximal.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge all of his co-authors on his manuscripts referenced in the present review.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

Francis Stephens is a scientific advisor to Beachbody Inc., USA.

Authorship

Francis Stephens wrote the present review. It is a summary of an invited presentation to the Nutrition Society Scottish Section.