Introduction

Effective, around-the-clock, co-ordinated care for people with advanced cancer and palliative care needs requires inter-agency working and communication (Thomas, Reference Thomas2000; Gysels and Higginson, Reference Gysels and Higginson2004). ‘Continuity’ is a multi-dimensional concept, which has been defined in many different ways (Haggerty et al., Reference Haggerty, Reid, Freeman, Starfield, Adair and McKendry2003). Interpersonal or ‘relational’ continuity is defined as being able to consult with the same trusted health-care professional over time, whereas ‘informational’ continuity is defined as the transfer of important information about prior events and circumstances between providers involved in the care of a patient (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Haggerty and McKendry2002; Haggerty et al., Reference Haggerty, Reid, Freeman, Starfield, Adair and McKendry2003).

In the United Kingdom, out-of-hours primary care services are commissioned by local primary care organisations and are operationally independent from daytime acute and primary care services. An out-of-hours primary care contact is initiated by telephone, when the patient or carer contacts the service to request help. The call is then triaged by a clinician before a decision as to the most appropriate management option (telephone advice, treatment centre appointment, home visit or sent directly to hospital). It is unlikely that out-of-hours clinical staff will have longstanding, personal relationships with the patients who request help, as such services tend to cover areas that encompass a number of individual general practices (National Audit Office, 2006). Within this context, relational continuity is not feasible. Out-of-hours staff do not have routine access to full National Health Service (NHS) records, which is particularly problematic when trying to ensure informational continuity for patients with complex needs. In reality, out-of-hours staff are solely reliant on information conveyed to them directly from the patient or carer, unless there are local systems for the transfer of information between providers. Within this context, health policy and guidance documents have highlighted the need to improve team-working and inter-agency communication between out-of-hours primary care and daytime services (Department of Health, 2006: Requirement 3, p. 5).

Qualitative research with patients who have palliative care needs and their carers has found that they place great value on ‘informational’ continuity when accessing out-of-hours care (King et al., Reference King, Bell and Thomas2004; Worth et al., Reference Worth, Boyd, Kendall, Heaney, Macleod, Cormie, Hockley and Murray2006; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Winder, Seamark, Seamark, Avery, Gilbert, Barwick and Campbell2011). We recently published the findings from a qualitative study undertaken with service users with palliative care needs accessing ‘Devon Doctors’ – a large out-of-hours primary care service catering for a population c.1.1 million in the South West of England. We reported that service users expected health-care professionals working in the out-of-hours service to have access to up-to-date information about them. Callers often had to repeat clinical details of their case each time they contacted the out-of-hours services, even when they had contacted Devon Doctors before. Some participants found it difficult to provide accurate information about their complex care needs over the telephone, whereas others reported the process to be distressing and frustrating (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Winder, Seamark, Seamark, Avery, Gilbert, Barwick and Campbell2011).

Two systems have been suggested as possible solutions for the transfer of information between daytime and out-of-hours services – handover forms (King et al., Reference King, Thomas and Bell2003; Riley, Reference Riley2005) and patient-held records (Chambers, Reference Chambers1998; Lattimer et al., Reference Lattimer, George, Thompson, Thomas, Mullee, Turnbull, Smith, Moore, Bond and Glasper1998). While patient-held records allow the patient and/or their carer to keep an accurate record of their current package of care, service users telephoning the out-of-hours will still be required to repeat detailed information from the records each time they telephone requesting support. The handover form can partially overcome this problem as relevant information can be added to out-of-hours primary care records by the primary care health professionals. However, the handover form will only function successfully if the daytime teams identify appropriate patients, activate messages and then keep them up-to-date and the out-of-hours staff act upon the contents.

There is evidence that handover forms are underused for patients with palliative care needs. One study covering four out-of-hours primary care services in England (Burt et al., Reference Burt, Barclay, Marshall, Shipman, Stimson and Young2004) found that such information was held for between 1% and 13% of the 183 patients with palliative care needs who made contact with the out-of-hours services. A more recent evaluation of all calls made to a general practitioner (GP) out-of-hours service in the Netherlands identified that 0.75% (1041/137 828) of all calls were for patients with palliative care needs. These calls were attributed to 553 patients, of whom only 25% (141) had information transferred to the service by their GP.

A recent audit of Devon Doctor's records also confirmed that handover forms appeared underused (S. Avery, 2007; personal communication). There was also considerable variation between individual general practices in terms of the number of messages activated per 1000 of the population for any cause (including palliative care) (Wright, Reference Wright2009). To improve the quality of care provided to patients with palliative care needs, Devon Doctors identified increasing the use of handover forms as a service priority. However, for handover forms to be successful, it must be workable for health-care professionals and acceptable to patients and carers. In this paper, we report work with service users and providers in Devon to explore why such forms might be underused, and then to use this information to optimise the design and implementation of the existing handover form system.

Methods

As qualitative research was undertaken to provide evidence to support service development, ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Somerset NHS Research Ethics Committee (Study reference number 08/H0205/45).

Design

The study aims required a collaborative, reflective and cyclical approach between the research team and the out-of-hours primary care provider. Our model of research and service development is consistent with an ‘action research’ framework (Waterman et al., Reference Waterman, Tillen, Dickson and de Koning2001; Freshwater, Reference Freshwater2005). This approach involves at least two stages of consultation with key informants and entails close collaboration with them in order to instigate practicable and appropriate improvements in the service. Two main phases of activity were undertaken.

Setting

NHS Devon and NHS Plymouth are two primary care organisations that provide services to a large, mixed UK population including inner-city, suburban and rural communities with varying levels of deprivation. Devon Doctors are contracted to provide out-of-hours primary care services to both organisations (with a combined adult population c. 900 000) and receive around 210 000 calls annually (for any cause; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Winder, Seamark, Seamark, Ewings, Barwick, Gilbert, Avery, Human and Campbell2008). The service has operated a paper-based handover form system for some time, using faxed forms sent through from general practices or community nursing teams on which information about the patient's medical condition and other relevant details can be written. Although faxed forms are still accepted, while the action research was being conducted an online system was activated by Devon Doctors in the autumn 2008. As practices and community nursing team staff are becoming increasingly computerised, Devon Doctors developed an online portal to enable staff to enter and edit messages directly onto a centralised ADASTRA® database used by the out-of-hours service. The online service included a specially designed template to be used for palliative care patients.

Participants

Participation in the qualitative study was voluntary. All individuals who were approached to take part received detailed participant information sheets (including reply sheet and pre-paid envelope) and were informed that they could withdraw at any point. A small sample (n = 8) of adult patients (and their carers) who had palliative care needs (any cause) and had used the out-of-hours primary care service in the past 12 months were invited to participate in a short interview. In view of their potential vulnerability, the patients and carers were identified and recruited through staff in a general practice and from a local hospice service. We only received details via reply sheets of patients/carers who were willing to take part. Devon Doctors provided the research team with a list of 45 out-of-hours practitioners, who were all invited to participate. Practice managers and lead GPs were approached in all general practices (71) in North Devon, Exeter and East Devon and Plymouth. The sample included those working in inner-city, urban and rural communities with varying levels of social deprivation and in a range of differently sized practices to ensure as wide a range of views as possible were obtained. Six focus groups were convened, corresponding to two in each of the three areas: one for out-of-hours staff and one for daytime staff.

Data collection

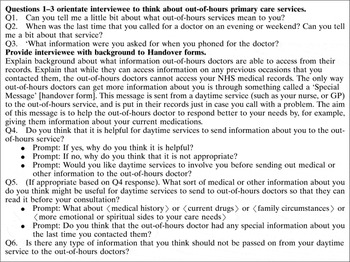

Patients were interviewed individually or with their carer as their complex palliative care needs made it inappropriate and impractical to conduct focus groups. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in September and October 2008 in the patients’ own homes. Following a topic guide (Box 1) developed in consultation with Devon Doctors, interviewees were asked to describe their recent experiences of using the out-of-hours service. The handover form system was explained to them and they were invited to comment on its usefulness and to suggest what information should be included in the form.

Box 1 Interview topic guide: patients and carers

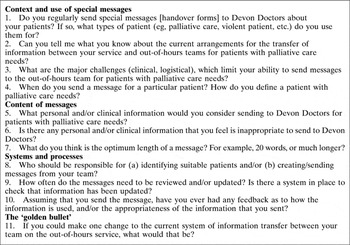

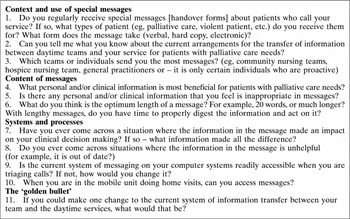

Focus groups were conducted with the health-care professionals. This method of investigation is recommended to explore attitudes and experiences of those working within a shared context (Kitzinger, Reference Kitzinger2006). Focus groups with health-care professionals took place between November 2008 and April 2009. Different topic guides were developed for daytime staff (Box 2) and out-of-hours staff groups (Box 3). Each group was facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher (A.A.), who ensured that all participants had an opportunity to contribute to the discussion. A moderator was used when groups exceeded four participants. Participants were encouraged to describe their understanding and experiences of the transfer of information between the daytime and out-of-hours services, to discuss their own use of handover forms (known locally as ‘special messages’), any problems they had encountered and to suggest ways of improving the system. Written consent was obtained from all participants at the time of interview or focus group.

Box 2 Focus group topic guide: daytime staff

Box 3 Focus group topic guide: out-of-hours primary care staff

Analysis

In phase one, interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim with the participants’ permission. All scripts were subsequently coded using the specialist computer-aided analysis package NVivo® (version 2.0) and codes were developed iteratively using the constant comparison method (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) to ensure that they were comprehensively applied. Established procedures of thematic analysis (Ritchie and Spencer, Reference Ritchie and Spencer1994; Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) were then undertaken. The categories and themes developed by the researcher (A.A.) were checked by members of the research team to ensure that codes had been applied systematically, accurately and appropriately, that no important issues had been overlooked and a balanced interpretation of the data was achieved.

Findings

Eight patients or carers agreed to participate in a short interview. Details of individuals approached, but who refused to take part are not available as the recruitment was handled through the clinical teams. Of the 45 clinicians identified by Devon Doctors, eight GPs and seven nurses agreed to participate. Fourteen staff were recruited from general practices (seven GPs, six nurses and one administrator). Due to a low response rate all those who replied to the invitation were recruited.

Phase One: interviews and focus groups

Interviews with patients and carers

When describing their recent experiences of using out-of-hours primary care, interviewees raised very similar issues to that reported in our previous research with advanced cancer patients and their carers (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Winder, Seamark, Seamark, Avery, Gilbert, Barwick and Campbell2011). Many interviewees expressed dissatisfaction with the requirement to repeat information when they contacted the service and some reported that giving accurate information can be problematic. Interviewees were surprised that out-of-hours services had no direct access to their primary care medical records, resulting in the need to rely upon details provided by callers. Interviewees were also unaware of the processes by which information might be passed between daytime and out-of-hours services (eg, handover forms), although most expected a system to be in place. When presented with the idea of a handover form, interviewees were invariably enthusiastic. They felt its use would absolve them from having to explain everything in detail. There was a strong feeling that a message would give them a sense of being ‘known’ at a time when they were usually experiencing a high level of distress:

And I had to tell them a bit of my history, or [partner's name] was helping me, because I couldn't speak, all my words wouldn't come out properly … I'm sure it [handover form] would be helpful because at least they could know a little bit of background about you, to have something there to see, because he was a complete stranger that didn't know my history at all and just worked on how I was at that time … you'd think that, in this day and age, with the computers, that you'd be able to put in a number of some sort and be able to just get what you want there. It wants sorting really… .(006 Patient)

I can't get my breath half the time, so it would save me talking … Well, it would help, wouldn't it? If they'd got it already, rather than them asking me questions, if they knew.(004 Patient)

When patients and carers were asked if they wished to be involved in formulating their handover form, all were entirely happy to allow their GP to construct it on their behalf:

The out-of-hours doctor and my own doctor, they're there to help my husband. So to me, whatever they need, they can have … not to worry about ‘oh should that be told?’, no, that shouldn't come into it … . I honestly think, the people that actually run this, would know what kind of message to put on it. Not the patient's family, because they're emotional, they're involved, I'd leave it to the experts.(002 Carer)

Focus groups with health-care professionals

All the health-care professionals had a positive view of handover forms, although areas for improvement were also identified. Out-of-hours staff felt that the messages enabled them to manage patients more sensitively and effectively, consistent with treatment being received through daytime services. Out-of-hours staff felt they were able to make better decisions in a situation where they were potentially ill-equipped to deal with problems and were in danger of making mistakes or initiating inappropriate hospital admissions. When no message was available, participants felt it was intrusive for patients to have to repeatedly give detailed information on the telephone:

I say to the patient when I'm triaging, I say “I'm really sorry to have to ask you about this, but we don't have all this information”.(201 out-of-hours GP)

Daytime staff thought that the messages provided much-needed informational continuity of care for their patients:

It means that you feel the patient has some sort of continuity of care and that over a weekend hopefully things won't go completely haywire … it just seems a very logical thing to do for patients who are having a clinically wobbly time … things that might be quite obvious because you've discussed them informally within your practice, but other doctors won't know.(212 daytime GP)

Three overarching concerns were articulated by the health-care professionals in the focus groups, which they felt should be addressed in order to improve the service, namely: (a) how handover forms are generated and maintained in the primary care setting; (b) how messages are sent and received in the out-of-hours service; and (c) the content of the forms.

In relation to the first area of concern, interviewees discussed how handover forms are generated and maintained in the primary care setting. The accounts of out-of-hours medical staff suggested that the practice of sending messages varied greatly in primary care both in terms of quantity and quality, and the standard was usually better when the practice had a specific interest in palliative care:

And there will be some practices where the people have a special interest who will always put better messages on than others … it's like all other things, there are some people who are interested and other practices who are not so interested.(205 out-of-hours GP)

Daytime staff were sometimes unclear about the precise function of the forms within the out-of-hours service, which was a potential discouragement to their use:

You need to know what a patient might get out of it, you know, whether it's worth doing … if it doesn't mean that anything in particular happens to them that's different or better, you wonder what the point is, and if it's worth cluttering up Devon Doctors with a lot of that sort of information.(216 daytime GP)

One daytime GP felt that the amount of information required on form needed to be clarified:

The difficulty is how much information the practices are going to give to [out-of-hours service]. I think that's not clear. I also work at the weekends, and sometimes the messages are very, very sketchy. Other practices provide very, very good and valuable information, the diagnosis, metastases and drugs and where the drugs are kept … so the two are there and I think they need to be standardised.(217 daytime GP)

There was reportedly no consistent practice for defining which patients should have a handover form. A message was sometimes not generated until the patient was put on the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP; Marie Curie Cancer Care, 2006), that is, in the last few days of life, and there was concern that patients who had not yet reached this stage would be missed, despite having similar needs:

It's mainly the ones on the LCP [who have a handover form], not those who have perhaps only had a change in their diagnosis or awareness of treatment, and they go home and they perhaps haven't taken it all in. That's a fragile group that there isn't always a message about. That's the ones I find a bit difficult to deal with.(101 out-of-hours nurse)

Some doctors and nurses felt that the Gold Standards Framework for Primary Care (Thomas, Reference Thomas2003), which clearly identifies patients in need of palliative care, should be used as the trigger for a handover form. This system was indeed being used by some daytime staff, although others felt it could generate too many forms and thus weaken the impact:

We don't routinely put all our Gold Standards Framework patients on there, because some of them are quiet and reasonably OK … There is a danger if you have too many people on it, it dilutes the thing to being just another register that nobody does anything about. Whereas we need it to actually mean something, for people to sit up and take notice of the message.(216 daytime GP)

In some cases a somewhat unformulated definition, similar to the ones described below, was being used:

I think it tends to be when there's a crisis, or when it's coming to a head, or when things are changing significantly or a lot of care is going in.(114 daytime nurse)

Maybe when they're undergoing perhaps symptom control, and things are difficult or there's a particular problem and, you know, there's an anxious family, or, you know, we would perhaps then do a special message.(117 daytime nurse)

There was also no consistent practice in terms of who was responsible for generating handover forms in primary care settings. In one geographical area the consensus was that this should fall to an allocated member of the administrative staff. One nurse reported how a doctor's receptionist in her practice had been given this role and kept the forms up-to-date:

She's brilliant, she gets the doctors organised. The doctors write on the special messages and she prints them off and gets the doctors to write any relevant information and keeps them in line. Really, she's worth her weight in gold.(112 daytime nurse)

Some participants, however, reported that this was not workable in their practice:

We've changed the admin. person in our practice and we're trying to get her to do it, but she says she's not happy to put on the special messages about the patients in case she gets it wrong … she's quite happy to remind people.(214 daytime GP)

In the absence of a nominated person responsible for the messages, nurses were often informally relied upon to prompt doctors to initiate them, which could be very time consuming.

The manner in which a handover form was generated within general practice also varied. Some practices used a weekly ‘Gold Standards Framework’ meeting to discuss messages, but for others this meeting was either non-existent or too infrequent to be useful, occurring perhaps every one to three months. Participants explored ideas about when forms could be processed, but sometimes it was difficult to identify a suitable time and place.

The out-of-hours participants reported that the handover forms available to them were often out-of-date and that this could cause them difficulties with clinical decision making, as other medical records were not immediately available:

You may be making the wrong assumption because you haven't got all the information. Remembering you don't have access to the patient's records, all you have is what the family tells you or what someone else said they heard the consultant say, you know, so a lot of it is guesswork.(201 out-of-hours GP)

There was a consensus that the out-of-hours service could be more proactive in keeping the forms updated. An automatic reminder would be useful, to alert practices to the messages they currently had on the system and requesting that these should be checked and updated.

In relation to the second major theme, interviewees reflected on how special messages are sent and received in the out-of-hours service. Discussions with the daytime staff revealed that handover forms were being sent to Devon Doctors in a variety of ways. The participants were split equally between those who were continuing to fax or phone messages through and those using the new online system. Sometimes restricted access to computers was a hindrance to sending messages electronically and some participants were unaware of the online facility. It was felt that more effort was needed to educate general practices about how to use the web-based system, particularly as faxed information was sometimes illegible.

The lack of online access for some out-of-hours staff, such as some nursing teams and those in mobile units, could also undermine the system. In such circumstances the medical staff were dependent upon call operators to read the message content out to them over the telephone, and practice seemed to be inconsistent:

The message is verbally transferred over to them by a call operator and it is very inconsistent whether the call operator highlights the special message. And so we may well find, in retrospect, that there has been a special message, but we didn't know, and that does happen.(106 out-of-hours nurse)

There was widespread concern about delays in the transfer of information between secondary and primary care. It could take several weeks after hospitalisation for important information to reach the GP and even longer for it to be incorporated into a handover form:

The difficult one is when they're more often seen on the ward, and that's when we don't get a lot of information. Supposing they're in and out of [name of ward] and so they're not getting get back to the practice very often, but they're coming home, that's where I see a problem … and that's often when a change of drug treatment has come and the patient has gone home with that change of drug treatment and then … the patients often don't have the knowledge.(103 out-of-hours nurse)

I think the hospital should be faxing out-of-hours as well, because that's where it sometimes breaks down. It can be two or three weeks before it gets to the GP.(117 daytime nurse)

Participants were also concerned that the ambulance services did not have access to handover forms, which could result in inappropriate hospital admissions or unwanted attempts to resuscitate:

There have been issues with regard to the ambulance service not being aware of the patient's status, whether it be status end-of-life, whether it be status on the Liverpool Care Pathway and therefore not for resuscitation, or whether it be status about their preferences about where they want to stay or not go. And that's not shared with the ambulance service.(104 out-of-hours nurse)

The final theme explored concerns about the variable content of handover forms. It was felt that an ideal form should contain information about the clinical situation including: the patient's diagnosis; recent changes in drugs and any adverse reactions; and medications held in the home. Clear medical information on the message would prepare them to treat the patient effectively and would avoid prolonged questioning:

It is much better when you're forewarned and you have an actual diagnosis, because sometimes the patient comes on, or a relative, and they know that they've got cancer, but they don't really know exactly where it is or what it involves, and you've to ask them lots of searching questions.(201 out-of-hours GP)

In addition, the form should also include information regarding social and practical issues such as: the patient's family circumstances and awareness of their medical condition; personal wishes with regard to place of care and resuscitation (where available); and how to gain access to the patient's home.

Phase Two: feedback from informants and implementation of results

Approximately one third of the participants responded (31%) to the guidelines for handover forms developed from phase one data: all felt that their views had been adequately represented and many made positive comments. Additional suggestions were that the Macmillan nursing service should contribute to handover forms and that details of the patient's hospital specialist should be included.

An action plan based on these results was devised in collaboration with the operational management team from Devon Doctors in June 2009 to help improve the system. The following actions were agreed and fully implemented by the service:

• Automatic reminders were instigated to all general practices 48 h before the handover form expired (based on a date set by clinician generating the form), requesting that they needed checking and updating.

• Online access to handover forms for all out-of-hours medical staff was improved.

• When online access was not available, out-of-hours service call operators are now trained to always read out the message to nursing teams and staff in mobile units.

• To raise awareness and to increase the use of handover forms (known locally as ‘special messages’), educational materials (desktop guide, newsletter) were sent to all general practices.

A further recommendation was not fully realised due to the need for further cooperation from secondary and ambulance services:

• To work with acute trusts to improve the transfer of information about patients with palliative care needs between hospital wards and the ambulance service.

In a subsequent meeting between the research team and the out-of-hours operational management team (July 2009), the production of a desktop guide for GPs was discussed. This was subsequently designed (Figure 1) and sent out electronically and in hard copy to all general practices in Devon. A special issue newsletter about handover forms was produced by Devon Doctors and sent out to practices in July 2009. This outlined the key research findings and set out the recommendations for how services might be redesigned to improve the use of messages both in the out-of-hours service and in general practice (Wright, Reference Wright2009).

Figure 1 A desktop guide to handover forms [special messaging] for primary care

Discussion

Main findings

Consistent with previous research, our service users valued informational continuity (King et al., Reference King, Bell and Thomas2004; Worth et al., Reference Worth, Boyd, Kendall, Heaney, Macleod, Cormie, Hockley and Murray2006; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Winder, Seamark, Seamark, Avery, Gilbert, Barwick and Campbell2011). When focussing specifically on the handover forms, patients and carers endorsed their use and thought it was important to improve communication between daytime and out-of-hours staff. Crucially, from a practical perspective, service users did not wish to be involved in its composition, instead trusting the clinicians involved in their care to disclose the appropriate information. These two findings are important, as it allowed daytime teams to be confident that this type of information sharing is acceptable, and that service users do not wish to be closely involved in the process of message generation.

Previous research has documented the underuse of information handover systems for patients with palliative care needs (Burt et al., Reference Burt, Barclay, Marshall, Shipman, Stimson and Young2004; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Blankenstein, Deliens and van der Horst2009b) and the inadequacy of the information transferred (Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Blankenstein, Willekens, Terpstra, Giesen and Deliens2009a). Our qualitative data from staff focus groups suggest that while health professionals valued the handover forms, they reported variable use of such forms in primary care, both in terms of quantity and quality. A number of barriers to their use were identified. There was no consistent practice in primary care for assessing the need for a patient to have a handover form or for generating and updating it. Some daytime staff were unsure of the value of these forms, were uncertain of what should be included and did not always appreciate how they benefited the patient and health practitioner. Out-of-hours staff valued the information contained in the handover forms, but described how they were often inadequate or missing. These findings supported the need for a structured, standardised handover form designed to prompt clinicians to complete specific information relevant for patients with palliative care needs. Out-of-hours services use handover forms for a variety of purposes (eg, identifying a potentially violent patient, etc.); our data support Devon Doctors’ decision to produce a version specific to patients with palliative care needs.

We also identified problems of incomplete access to the appropriate information technology systems supporting handover forms, especially for out-of-hours staff in mobile units and some community nursing teams. Although ambulance staff working for the acute trust might also benefit from accessing such information, there are no arrangements in place to allow this. Similarly, direct input of information from hospital staff regarding changing management plans is vital, rather than relying on general practice staff to input the information upon receipt of discharge summaries.

Reassuringly, the content of the pre-existing paper-based and online handover forms already mapped closely onto the areas that our sample identified as important, although some small improvements were made in light of feedback. Our implementation strategy therefore focused more on raising awareness of when and how to use the system by providing short educational materials (desktop guide) and a newsletter. Qualitative evidence also strengthened the case for the out-of-hours service to improve computer access to previously under-served groups (eg, mobile units, out-of-hours nursing teams). This work also resulted directly in the out-of-hours database being modified so that 48 h before the date specified for message expiry (as specified by the clinician) an automated reminder to review existing messages was set up. Devon Doctors use an operating platform used by an estimated 90% of UK out-of-hours primary care services (Adastra©, 2010), suggesting a small ‘IT fix’ could have a wide impact if implemented across their client base.

Strengths and limitations

By consulting the health-care professionals working in daytime and out-of-hours service, as well as the patients and their carers, it was possible to identify how the information transfer system worked and its limitations. The use of an action research model enabled the research team to identify specific problems in the local system through close consultation with providers and service users and to offer practicable solutions. The close partnership with the local out-of-hours primary care service also ensured that, where possible, recommendations could to be promptly implemented.

It is possible that the qualitative study attracted participants with a special interest in palliative care and might not reflect the views of all primary care health professionals. In addition, the qualitative study may lack generalisability due to the ‘local’ nature of the data collection. The existing literature (Burt et al., Reference Burt, Barclay, Marshall, Shipman, Stimson and Young2004; Worth et al., Reference Worth, Boyd, Kendall, Heaney, Macleod, Cormie, Hockley and Murray2006) and local audit data (Wright, Reference Wright2009) indicate that there are too few handover forms for patients with complex needs: if even health professionals with an interest are unsure about their value this would suggest that there is even greater need for information about this to reach all health professionals.

Our partner, Devon Doctors, have a long-standing commitment to improving the experience of seeking out-of-hours care for patients with palliative care needs and their families. While many of the key findings were quickly implemented by Devon Doctors some problematic areas, such as the accessing of handover forms by ambulance staff or encouraging hospital staff to contribute messages, require potentially challenging service redesign at the interface between out-of-hours primary care and acute NHS providers. Although keen to quickly resolve these problems, Devon Doctors cannot act unilaterally as the other providers must commit to service redesign. At the time of writing (2010), a multi-stakeholder service redesign initiative was in the advanced planning stages. The ‘Devon Palliative Care Register (ADASTRA)’ hosted by Devon Doctors is scheduled for implementation (2010–12), and will support advance care planning by identifying patients’ approaching end of life, recording their preferences and making this available across all NHS Trusts and agencies 24 h a day, seven days a week to ensure adherence to the patients preferences.

Finally, although we used an action research framework, involving at least two cycles of collaborative, reflective work between the researchers and providers, we are unable to fully test the impact of this work. Our funding supported two stages of consultation that allowed development and implementation of the desktop intervention and newsletter, both of which were intended to raise awareness and ultimately to increase the uptake of handover forms. Similarly, the automated reminders should improve the regularity with which the forms are reviewed and updated. Ideally, further audit work is required to test whether these measures have improved practice, but we were unable to undertake this due to logistical constraints.

Conclusions

This work highlighted the need to raise awareness and to educate health-care professionals to improve the use of handover forms for patients with palliative care needs. Further work is needed to test whether simple interventions, such as an educational desktop guide to handover forms and automated reminders to update existing messages, can improve informational continuity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Scientific Board of the Royal College of General Practitioners (SFB/2007/07), the BUPA Foundation and Macmillan Cancer Support for funding this work. The Primary Care Research Network (South West) contributed service support costs and facilitated staff recruitment. We are grateful for the contributions of the out-of-hours and in-hours NHS staff contributing their time and experiences. Special thanks are due to the staff of the Devon Doctors out-of-hours primary care service, who actively partnered this project. We thank the North Devon Hospice and St Luke's Hospice in Plymouth who accommodated some of the focus group meetings and Dr Jim Gilbert at Exeter Hospiscare, who contributed to the research team discussions. Finally, we thank the patients and their carers who generously gave their time and shared their experiences with us.