Background

Pharmaceutical care was first defined by Brodie (Reference Brodie1967) as ‘the care that a given patient requires and receives which assures safe and rational drug use’. Hepler (Reference Hepler1987) refined this concept as a ‘covenantal relation between a patient and a pharmacist’. Hepler and Strand (Reference Hepler and Strand1990) went further with this definition to include the provision of drug therapy and quality-of-life outcomes, and in further landmark studies in the USA developed the practice of pharmaceutical care.

We have followed Hepler and Strand’s (Reference Hepler and Strand1990) definition of pharmaceutical care as ‘the responsible provision of drug therapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life’, these being (a) cure of a disease, (b) elimination or reduction of a patient’s symptoms, (c) arresting or slowing of a disease process or (d) preventing a disease or symptom. The term ‘medicines management’ is commonly used synonymously in the UK (Simpson, Reference Simpson2001; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Campion, Coulton, Cross, Edmondson, Farrin, Hill, Hilton, Philips, Richmond and Russell2004).

The RESPECT (Randomised Evaluation of Shared Prescribing for the Elderly in the Community, randomised over Time) trial (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Campion, Coulton, Cross, Edmondson, Farrin, Hill, Hilton, Philips, Richmond and Russell2004) was designed to evaluate the impact of pharmaceutical care on the appropriateness of prescribing for patients aged 75 years or older. Community pharmacists across five Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) provided pharmaceutical care to over 700 patients for 12 months in a randomized time series sequence. All participating pharmacists received training in the provision of pharmaceutical care. This included two 3-hour meetings, and some ‘pre-workshop tasks’ or homework, covering conducting medication reviews and constructing care plans. In one of the two training evenings, general practitioners (GPs) and their local community pharmacists were ‘paired up’, with the aim of opening up communication and beginning the professional liaison, which is an important part of pharmaceutical care.

According to Dinnie et al. (Reference Dinnie, Bond and Watson2004), who conducted two focus groups with community pharmacists in Scotland, there had been little research to examine the attitudes of pharmacists regarding medicines management. The themes that were identified from their study included differences in the understanding of the term ‘medicines management’, practical concerns regarding the facilities and capabilities, the patient–pharmacist relationship and the pharmacist–GP relationship. There were concerns about whether community pharmacists could deliver a medicines management service.

Hughes and McCann (Reference Hughes and McCann2003) in a focus group study in Northern Ireland explored the perceived inter-professional barriers between community pharmacists and GPs. The GPs perceived the community pharmacists as ‘shopkeepers’, who had limited opening hours. Community pharmacists who participated in the focus groups: ‘felt such views influenced their position on the hierarchy of health-care professionals,’ and felt that ‘GPs are very reluctant to relinquish any sort of control to us’. Hughes and McCann concluded that a number of barriers still existed between the two professions.

Towards the end of the RESPECT trial, we invited all participating pharmacists to attend a focus group arranged in their area, to discuss the trial and its implications. We wanted to see how such an imposed process had impacted on their practice, and what had been the perceived barriers to full implementation of ‘pharmaceutical care’. Focus groups are a form of group interview, used to gather data for qualitative analysis (Morgan, Reference Morgan1997; Barbour and Kitzinger, Reference Barbour and Kitzinger1999). They are particularly appropriate where members of the groups bring different perspectives to bear on a topic, such that the group discussion leads to a synthesis of ideas and to a refining of the question.

Method

We recruited four groups from participating pharmacists, meeting at neutral locations accessible to one or more of the five PCTs involved in the trial. Each pharmacist who had participated in the RESPECT trial was invited to attend a focus group, initially with a telephone call, which was followed up with a letter. We obtained consent from each pharmacist for the discussion to be recorded and transcribed.

The focus groups were held between 2 and 7 months after the intervention stage of the trial, between April 2004 and April 2005. Although pharmacists were paid for their professional time in the RESPECT trial, they were not paid to attend the focus group. In total, 21 pharmacists completing the trial attended the four focus groups, out of the 53 who had been active in the trial. Those 32 pharmacists who did not attend the focus group (reasons were not always disclosed) were sent an anonymous questionnaire. This was written after analysing the first focus group, using the themes that had emerged, and contained both open and closed questions designed to elicit similar information to the focus groups. Examples of these questions included ‘Was the training effective for what you were required to do?’ and ‘When reviewing the patients during the trial intervention what, if any, problems did you encounter?’. In all, 14 responses were received, a response rate of 44%.

Participants within each focus group represented a range of pharmacy types (multiples, independents and small chains). We did not record individual pharmacists’ demographic data.

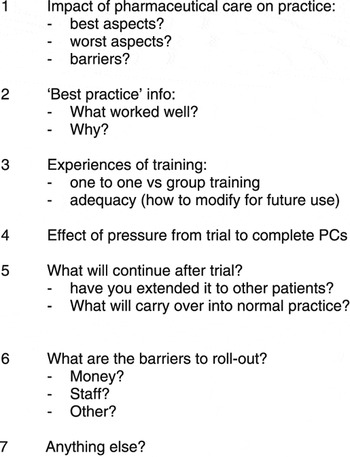

Each focus group began with a general question about the impact of pharmaceutical care on practice. The moderator loosely followed a topic guide (see Figure 1) designed to elicit the sort of information we were seeking, but which allowed the discussion to flow freely, letting the pharmacists also raise whatever other issues they chose. The moderator often intervened to explore a topic in more detail, seeking clarification of points raised by the group. Usually, the group spontaneously addressed most of the expected topics, without being prompted.

Figure 1 Focus group Topic Guide

The groups were moderated by an independent researcher (GI) not involved in the trial, with a second person taking notes to assist the transcription. All groups were recorded and transcribed in full. Extracts are presented with codes A to D for the four focus groups, and numbers indicating different members, with ‘mod’ for the moderator.

Analysis

All three authors independently read the (anonymized) transcripts, and identified emerging themes. We met together to discuss the themes, and reconcile discrepancies. We re-read all the data until no new themes emerged. Written responses in the questionnaires from non-attenders were read in the same way, and incorporated into the analysis.

Findings

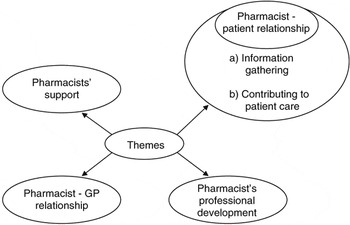

We identified four main themes (also see Figure 2):

Figure 2 Themes identified

1) issues around the pharmacist–patient relationship

2) problems with the pharmacist–GP relationship

3) the pharmacists’ professional development

4) the pharmacists’ support

1. The effect of the RESPECT trial on pharmacist–patient relationships

Pharmacists described in the most positive terms a new level of professional relationship with patients.

Information gathering

The patient review process within the trial required the pharmacist to make monthly contact with the patient. This could be done by either making a telephone call to the patient, visiting them in their own home or the patient visiting the pharmacy. The general consensus was that the most valuable information was gathered by visiting the patient in their own home, where ‘discoveries’ could be made of hoarding, or other deviations from intended treatments.

When asked to contrast home visits with telephone encounters, one group concluded that face-to-face encounters were superior to telephone, a finding repeated in all the groups.

Not on the phone, either in the pharmacy or going to their homes. Well, initial visits were good, I felt, but the other visits later in the year were better. Probably because they were more used to it. Or sometimes they’d pop into the shop for their review and we’d check through things. So face-to-face, definitely.

(B3)

The improved relationship between the pharmacists and their patients increased the pharmacists’ ability to detect ‘hidden’ medications, and potentially improve patient compliance.

Contributing to patient care

Pharmacists were asked about the positive experiences they would take away from their participation in the trial. A number of pharmacists talked about the improved relationship and understanding between themselves and the trial patients, and the way this addressed directly issues of patient care.

Personally, I feel that the interventions we made, especially when we made them, were particularly useful to the patients in terms of, they know we are there to help them with their medications; are they experiencing any problems?; are they complying?; and things like that. They felt very reassured and satisfied with the whole project. That people were there for them when they needed them.

(A2)

I had one lady who took her medication at 4am and I thought it was strange – then I found out she only had one toilet and it was upstairs and she had bad knees that made it difficult to go up and down to the toilet.

(D1)

These pharmacists felt they had acquired a new skill of clinical involvement, based on both their enhanced knowledge and their ability to interact with patients on a more clinical level. It was notable that the pharmacists enthused about the added dimension to their role.

2. The effect of the RESPECT trial on the relationships between pharmacists and GPs, and therefore making a difference to prescribing

Surgeries varied in their efficiency in dealing with requests for meetings, but were better when this role was taken by the administrative staff rather than by the GPs. GPs were less than helpful in the perception of many of our pharmacist respondents:

Another barrier: GP response! We send out our info in an envelope and say ‘please sign and return’. By the time they come back to us, some take 4 weeks if at all, they eventually get back to us.

(A2)

The same group discussed how the trial had improved their relationships with GPs:

How do the others feel about relationships with GPs as a result of the trial?

(Mod)

Yeah, it’s good. Cos we did make some good interventions, yeah? ……. So after the first six months, a year, the GP contacts are good, you speak to them and they’re quite positive.

(A4)

These pharmacists had not felt comfortable in the role of ‘prescribing adviser’. One group member asked their group:

We, you do sometimes give prescribing advice to GPs…

(A6)

On an ad hoc basis, yes.

(A3)

[General agreement]

How will that work? Has the RESPECT trial made a difference to how you’ll do that?

(Mod)

I might be more inclined to put something down on paper, em, to the GP as a way of drawing their attention to it. I’ve sometimes thought, ‘well, should I write this in a letter?’ which I wouldn’t have thought before. But I don’t know whether that’s for a number of reasons, it might be because I’m used to putting things down on paper and seeing a response.

(A6)

Prior to the trial, this pharmacist would not have presumed to send such a recommendation in writing to a GP, but since the intervention, they felt they could. It does seem that pharmacists, as a group, felt uncomfortable in a professional relationship with the GPs whose prescriptions they dispensed. They expressed this in terms of GPs’ attitude towards pharmacists, as the following exchange, around ‘rolling out’ the intervention, illustrates:

Can I just add to that – the GPs’ willingness to take part seems relevant from where I’m at. Cos one of my GPs was not really… keen.

(A5)

Yes.

(A6)

They’re not really keen to be bothered to do anything for it…Even though they’re getting paid for it, they don’t really pay any attention to it. Losing care plans, and so on, and so forth.

(A5)

That’s your experience is it? [Some agreement]

(Mod)

And although the intervention required regular contact between GPs and pharmacists, the perception was less than enthusiastic:

I think three months into the exercise some GPs lost interest; I got the distinct feeling that they were just signing things like they would a repeat prescription. They probably didn’t even look at what they were signing.

(C2)

The intervention required both the pharmacist to identify an issue in the prescribing and the GP to take some action on receiving the pharmacist’s care plan. Some pharmacists felt their efforts were wasted through GPs ignoring their suggestions.

I did feel sometimes though that I was wasting GP time. You can initiate changes but you still have to have the agreement of the GP to make changes.

(C4)

Not every pharmacist was struggling to achieve a working relationship with GPs. B3 had been able to build on one good relationship to create, by ‘hard work’, an effective relationship with a second practice.

I have to say the relationship I have with the other surgery which is further away is much harder work. Because we just didn’t have the same relationship. It worked out ok but it was just harder work.

(B3)

The process of writing ‘care plans’ to be shared with the GP was novel for these community pharmacists, although it was apparent from the training that some hospitals had introduced them.

Something that the RESPECT trial did, was the way care plans are presented, it opened my eyes to what needed to be written in care plans and how they should be presented. Because that’s not something… we don’t normally write care plans as pharmacists.

(A2)

So although participating pharmacists carried out regular reviews of patients’ medication, and routinely submitted these to the prescribing GPs for comment, their experience was that GPs did not engage as fully as they would have liked in the process. The very thought of going and speaking to a GP was alarming for some of these pharmacists.

3. Pharmacists’ professional development in relation to patients and awareness of learning needs

Pharmacists spoke of their improved professional development as a result of taking part in the trial, especially the improved understanding of the conditions of the patients and the problems the patient might face in dealing with their condition. The pharmacists found themselves reflecting on what they did not know, and seeking information in order to better perform their new role.

I think it left me panicking somewhat about the gap in my clinical knowledge that was hovering above my head… or seemed to be over my head. That… the sort of things I was expected to carry out, perform, remember, whatever.

(A5)

It makes you think about your own practice and what you can do in the given restraints, to make it better. It can almost make you feel a bit… I could do this better.

(A6)

For most pharmacists, the task of reviewing the clinical care and creating care plans was an enormous stimulus to learning. It was as if the trial had added a new dimension to their work that required a ‘paradigm shift’ in their personal development.

I found it slightly frustrating because, em, I didn’t think I knew quite enough about the patient and his total care… And I didn’t think I had enough knowledge… well, medical knowledge partly, although I tried like mad to find out as much as I could.

(D1)

The enhanced knowledge led to a new responsibility: to inform patients to a greater extent about the nature of their illnesses and treatments.

4. Pharmacists’ peer support

It emerged during the discussions that these pharmacists had found the trial valuable in the way it offered the opportunity to link them together in a ‘learning community’, through the training and the shared involvement. However, there remained very little actual meeting between participating pharmacists.

I think it’s always useful to talk to other pharmacies and we don’t really get a huge amount of time to do that. Or opportunity, but yes, it is reassuring when you talk to other people and they have done the same as you, thought the same as you, because you work in isolation most of the time.

(B3)

Have you had contact with each other on the RESPECT trial? [Everyone says ‘no’]

(Mod)

we’re very bad at that as pharmacists.

(B2)

Being involved in this large trial had brought pharmacists together in a way that they found professionally helpful. Even those who worked for the same ‘multiple’ were otherwise not in contact. This finding emerged rather as a ‘side effect’ of the trial, an unintended but beneficial consequence of bringing together relatively isolated professionals in learning and performing a common task.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the power of the focus group approach, as it enabled these independent and often professionally isolated pharmacists to meet and interact, and thereby generate ideas in a shared way that might not have been achieved through individual interviews. This professional group has had an image problem as ‘shopkeepers’ (Hughes and McCann, Reference Hughes and McCann2003), which belied their undoubted therapeutic role and skills (Bellingham, Reference Bellingham2004; Department of Health, 2005a). Our data indicate that given appropriate support, both financial and professional, pharmacists can exercise a valuable clinical role in the care of people in the community. We also found that the attitudes of the GPs in the study, despite having been invited to, and in many cases, actually attending, shared training events, during which they met and shared case studies with their respective pharmacists, were perceived as being less than helpful towards the pharmacists who tried to liase over particular patients. Our respondents were clear that dialogue with GPs was difficult, that GPs did not always treat them as colleagues, but that GP practice staff could exert a facilitative role in this communication. There almost seems to be an ‘institutionalized discrimination’ in general practice against pharmacists.

More positively, these pharmacists had discovered a new clinical dimension to their work, by having to compile ‘care plans’, which related treatment to illness and symptoms, they found themselves enquiring more thoroughly into the patients’ problems. As the role of pharmacy expands, educational curricula, both undergraduate and postgraduate and continuing, will need to incorporate more of these clinical competencies (Dewdney, 2002; Nathan, Reference Nathan2006; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Loftus, Christou, Eggleton and Norris2006; Taylor and Harding, Reference Taylor and Harding2007).

Medicines use reviews (MURs) (Bellingham, Reference Bellingham2004), now widely implemented through the new Pharmacy Contract, will be of limited benefit unless the prescribers (ie, usually GPs) are prepared to first read the reviews, to recognize the professionalism of the pharmacists, and are prepared to enter into dialogue to develop the ideas in the reviews. Hawksworth et al.’s (Reference Hawksworth, Corlett, Wright and Crystyn1999) descriptive study did suggest that GPs engaged with pharmacists in point-of-dispensing interventions, and that these interventions could be clinically significant. Our study shows that there may be some way to go before GPs and community pharmacists really work together as colleagues.

Pharmacists become involved in prescribing in many ways: through minor ailments schemes (in effect an extension of ‘over-the-counter’ advice), by supplying against a Patient Group Direction (Department of Health, 2000), essentially a protocol-driven role, as ‘supplementary prescribers’ (Department of Health, 2005b), where pharmacists will take on the role of a full prescriber, within the framework of a clinical management plan (CMP), and recently as ‘independent prescribers’ (Department of Health, 2006). As prescribers, pharmacists will need to have better relationships with their GPs than we have seen in this study. As trained independent prescribers, pharmacists might feel more empowered and less inferior to their GP colleagues.

Whatever the economic and pharmaceutical impacts of the RESPECT intervention, our data here suggest that as they became more involved with the actual prescribing decisions by producing and discussing care plans with the GPs, these pharmacists found greater fulfilment and believed that by empowering patients they were having an impact on concordance. However, our study suggests that the training of pharmacists in the past may not be congruent with their emerging extended role in medicines management.

Declaration

The RESPECT trial original protocol obtained Ethics Committee approval. The RESPECT trial was funded by the Medical Research Council, and the five PCTs (West Hull, Eastern Hull, East Yorkshire, Yorkshire, Wolds & Coast, and Selby & York).